Abstract

This report describes phase 1 clinical trials performed to assess interactions of oral isavuconazole at the clinically targeted dose (200 mg, administered as isavuconazonium sulfate 372 mg, 3 times a day for 2 days; 200 mg once daily [QD] thereafter) with single oral doses of the cytochrome P450 (CYP) substrates: bupropion hydrochloride (CYP2B6; 100 mg; n = 24), repaglinide (CYP2C8/CYP3A4; 0.5 mg; n = 24), caffeine (CYP1A2; 200 mg; n = 24), dextromethorphan hydrobromide (CYP2D6/CYP3A4; 30 mg; n = 24), and methadone (CYP2B6/CYP2C19/CYP3A4; 10 mg; n = 23). Compared with each drug alone, coadministration with isavuconazole changed the area under the concentration‐time curves (AUC∞) and maximum concentrations (Cmax) as follows: bupropion, AUC∞ reduced 42%, Cmax reduced 31%; repaglinide, AUC∞ reduced 8%, Cmax reduced 14%; caffeine, AUC∞ increased 4%, Cmax reduced 1%; dextromethorphan, AUC∞ increased 18%, Cmax increased 17%; R‐methadone, AUC∞ reduced 10%, Cmax increased 3%; S‐methadone, AUC∞ reduced 35%, Cmax increased 1%. In all studies, there were no deaths, 1 serious adverse event (dextromethorphan study; perioral numbness, numbness of right arm and leg), and adverse events leading to study discontinuation were rare. Thus, isavuconazole is a mild inducer of CYP2B6 but does not appear to affect CYP1A2‐, CYP2C8‐, or CYP2D6‐mediated metabolism.

Keywords: cytochrome P450, interaction, isavuconazole, isavuconazonium, pharmacokinetics

Invasive fungal diseases are a growing healthcare burden and are associated with significant morbidity and mortality.1, 2 Patients with hematological malignancies, undergoing transplants, and receiving immunosuppressive therapy are particularly susceptible due to their immunocompromised state.3 However, existing therapies are limited in their efficacy and safety, especially against rarer and resistant pathogens, and new antifungal agents are urgently needed.

Isavuconazonium sulfate is the water‐soluble prodrug of the triazole antifungal agent isavuconazole and is available in cyclodextrin‐free oral and intravenous formulations.4, 5 Isavuconazole disrupts biosynthesis of ergosterol, an essential component of fungal cell membranes.6, 7 On the basis of results in the SECURE trial8 and the VITAL trial,9, 10 isavuconazonium sulfate has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the primary treatment of adult patients with invasive aspergillosis or invasive mucormycosis. It also has been approved by the European Medicines Agency for the primary treatment of adult patients with invasive aspergillosis and treatment of patients with mucormycosis for whom treatment with amphotericin B is inappropriate.

Establishing isavuconazole's drug‐interaction profile is important because it may be prescribed for patients with coexisting illnesses who typically require a number of concomitant medications. Because plasma concentrations observed with clinically recommended dosing (200 mg 3 times daily [TID] for 2 days, then 200 mg daily) typically are <7 μg/mL (data on file), IC50 or Ki values of ≤16 μmol/L might be the most clinically relevant (isavuconazole molecular weight, 437.47 g/mol). Isavuconazole has demonstrated weak inhibition of the transporters P‐glycoprotein (P‐gp; in P‐gp–transfected porcine kidney epithelial cell monolayers, inhibition constant [IC50] with [3H]digoxin substrate, 25.7 μmol/L), organic cation transporters 1 and 2 (OCT1 and OCT2; in stably transfected human embryonic kidney [HEK293] cells, IC50 for OCT1 with [14C]tetraethylammonium bromide substrate, 3.74 μmol/L; IC50 for OCT2 with [14C]metformin substrate, 1.97 μmol/L), and multidrug and toxin extrusion protein 1 (in stably transfected HEK293 cells, IC50 with 14C‐metformin substrate, 6.31 μmol/L; see also Yamazaki et al11), as well as weak inhibition of uridine diphosphateglucuronosyl transferase (in human liver microsomes, IC50 for 17β‐estradiol 3‐glucuronidation [UGT1A1], 9.0 μmol/L; propofol glucuronidation [UGT1A9], 19 μmol/L; morphine 3‐glucuronidation [UGT2B7], 44 μmol/L; see also Groll et al12). It is also a sensitive substrate and moderate inhibitor of CYP3A4 (66.2% metabolized in CYP3A4‐expressing pooled human liver microsomes; the Ki of isavuonazole for midazolam and testosterone, 0.62 μmol/L and 1.93 μmol/L, respectively; see also accompanying manuscripts12, 13). However, interactions with other important CYP isoenzymes involved in drug metabolism are not documented.

In studies using human liver microsomes in vitro, isavuconazole has been identified as an inhibitor of CYP1A2 (IC50 38.5 μmol/L), CYP2B6 (IC50 15.1 μmol/L), CYP2C8 (IC50 5.07 μmol/L), CYP2C9 (Ki 4.78 μmol/L), CYP2C19 (Ki 5.40 μmol/L), and CYP2D6 (Ki 4.82 μmol/L), but not CYP2A6 or CYP2E1 (IC50 >100 μmol/L; data on file). In experiments performed in cultured human hepatocytes, isavuconazole was also shown in vitro to be an inducer of CYP2B6 (increases up to 13.4‐fold and 11.4‐fold in bupropion hydroxylase activity and mRNA, respectively), and to a lesser extent CYP3A4 (increases up to 3.4‐fold and 6.4‐fold in testosterone hydroxylase activity and mRNA, respectively), CYP2C8 (increases up to 2.6‐fold and 4.3‐fold in amodiaquine N‐dealkylase activity and mRNA, respectively), CYP2C9 (increases up to 3.1‐fold in diclofenac 4ʹ‐hydroxylase activity only), and CYP1A2 (increases up to 2.8‐fold and 5.4‐fold in phenacetin O‐dealkylase activity and mRNA, respectively; data on file). In this article, we report the results of phase 1 trials using substrate probes to assess potential in vivo CYP‐mediated interactions of isavuconazole with bupropion (CYP2B614), repaglinide (CYP2C8; also a substrate for CYP3A415), caffeine (CYP1A216), dextromethorphan (CYP2D6; also a substrate for CYP3A417), and methadone (CYP2B6, CYP2C19, and CYP3A418, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26), most of which are specified in regulatory guidance from the US FDA and European Medicines Agency.

Methods

Study Design

Study protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board for each participating study site (bupropion study, Independent Investigational Review Board, Inc., Plantation, Florida; caffeine/repaglinide, dextromethorphan, and methadone studies, Aspire IRB, LLC, Santee, California). All studies were conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, Good Clinical Practice, International Conference on Harmonisation guidelines, and local regulations. Participating subjects provided written, informed consent in advance of any study procedures.

These were phase 1, single‐center, open‐label, drug‐interaction studies conducted to evaluate potential interactions between isavuconazole (administered as isavuconazonium sulfate; CRESEMBA® oral capsules; Astellas Pharma US, Inc., Northbrook, Illinois) and the CYP substrate probes. Study centers, trial registration numbers, and dates of the study for each drug were as follows: bupropion hydrochloride (WELLBUTRIN® oral tablets, GlaxoSmithKline, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina), Clinical Pharmacology of Miami (Miami, Florida), NCT01635972, May to July, 2012; repaglinide (PRANDIN® oral tablets, Novo Nordisk Inc., Princeton, New Jersey); and caffeine (VIVARIN® oral tablets, GlaxoSmithKline), PAREXEL Early Phase Clinical Unit (Baltimore, Maryland), NCT02128321, January to February, 2014; dextromethorphan hydrobromide (ROBITUSSIN® oral capsules, Pfizer Inc., New York, New York), PAREXEL Early Phase Clinical Unit (Baltimore, Maryland), NCT01651325, May to July, 2012; and methadone hydrochloride (DOLOPHINE® oral tablets, Roxane Laboratories, Inc., Columbus, Ohio), PAREXEL International (Glendale, California), NCT01582425, May to July, 2012.

Adult, medication‐free, male and female subjects, aged 18 to 55 years, weighing ≥45 kg, with a body mass index (BMI) of 18 to 32 kg/m2, and with no clinically significant coexisting disease history, were eligible to enroll in these studies.

Dosing and Sampling Schedules

In this report, dosing information is expressed as the isavuconazole equivalent of the prodrug: oral capsules each contained isavuconazonium sulfate 186 mg, equivalent to isavuconazole 100 mg. The clinically targeted dose of isavuconazole was 200 mg TID loading dose (administered as isavuconazonium sulfate 372 mg) for 2 days, followed by 200 mg QD.

Bupropion

Subjects were screened (from day –21 to day –2) and checked in at the study center (day –1), where they remained until day 21. A follow‐up visit was conducted on day 27 (±2 days).

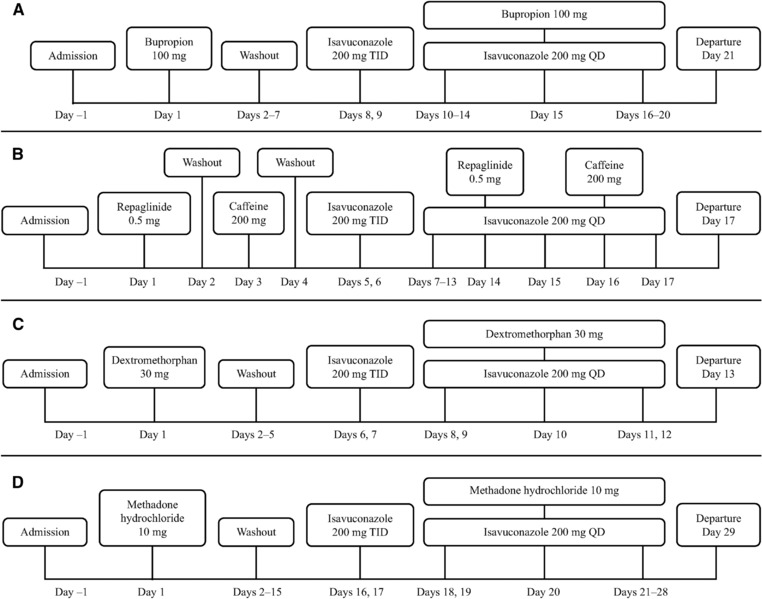

On day 1 of the study, subjects received a single oral dose of bupropion hydrochloride 100 mg, followed by a 7‐day washout period (Figure 1A). On days 8 and 9, subjects received oral isavuconazole 200 mg TID (8 hours apart), then 200 mg QD on days 10 to 20. Subjects received a further single oral dose of bupropion hydrochloride 100 mg concurrently with isavuconazole on day 15. Subjects fasted for ≥10 hours prior to bupropion hydrochloride administration and continued to fast for 4 hours following administration. On day 15, isavuconazole was administered immediately before bupropion hydrochloride.

Figure 1.

Clinical study designs. QD, once daily; TID, 3 times a day. Isavuconazole 200 mg was administered as isavuconazonium sulfate 372 mg.

Blood samples were collected for pharmacokinetic (PK) analysis of bupropion and its metabolite, hydroxybupropion, at predose and at 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 16, 20, 24, 48, 72, and 96 hours postdose on days 1 and 15. Additional samples were also drawn at 120 and 144 hours postdose on day 15. Samples for PK analysis of isavuconazole were collected at predose and at 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 16, 20, and 24 hours postdose on days 14 and 15.

Repaglinide and Caffeine

Subjects were screened (day –28 to day –2) and checked in to the study center (day –1), where they remained until day 17. A follow‐up telephone call was made on day 24 (±2 days).

Participating subjects received a single oral dose of repaglinide 0.5 mg on day 1 and a single oral dose of caffeine 200 mg on day 3 (Figure 1B). After a short washout period, subjects received oral isavuconazole 200 mg TID (8 hours apart) on days 5 and 6, then 200 mg QD on days 7 to 17. Subjects also received additional single oral doses of repaglinide 0.5 mg and caffeine 200 mg concurrent with isavuconazole on days 14 and 16, respectively. For doses on days 1, 3, 13, 14, and 16, subjects fasted for ≥10 hours prior to dosing and continued to fast for 4 hours after administration.

Blood samples were collected for PK analysis of repaglinide on days 1 and 14 at predose and at 0.5, 0.75, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 12, and 24 hours postdose; and for PK analysis of caffeine/1,7‐dimethylxanthine on days 3 and 16 at predose and at 0.5, 0.75, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 12, 24, 36, and 48 hours postdose. Samples for PK analysis of isavuconazole were collected at predose and at 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 12, and 24 hours postdose on days 13, and 14 as well as at predose and at 0.5, 0.75, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 12, 24, 36, and 48 hours postdose beginning on day 16.

Dextromethorphan

Subjects were screened (day –28 to –2), before check‐in at the study center (day –1), where they remained until the end of study procedures (day 13). Subjects returned to the study center for a follow‐up visit on day 21 (±2 days).

On day 1, subjects received a single dose of oral dextromethorphan hydrobromide 30 mg (Figure 1C). Following washout, subjects received oral isavuconazole 200 mg TID (8 hours apart) on days 6 and 7, then 200 mg QD on days 8 to 12. On day 10, subjects also received a single oral dose of dextromethorphan hydrobromide 30 mg concurrent with isavuconazole. Subjects fasted for ≥10 hours prior to dextromethorphan hydrobromide administration and continued to fast for 4 hours following administration. On day 10, isavuconazole was administered immediately before dextromethorphan hydrobromide.

Blood samples were collected for PK analysis of dextromethorphan and its metabolite, dextrorphan, at predose and at 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, 12, 16, 20, 24, 48, and 72 hours postdose on days 1 and 10. Samples were also collected for PK analysis of isavuconazole at predose and at 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, 12, 16, 20, and 24 hours postdose on days 9 and 10. In order to evaluate the impact of the effect of genetic polymorphism of the CYP2D6 enzyme on dextromethorphan metabolism, 1 sample was collected prior to dosing on day 1 for analysis of genotyping for CYP2D6 *2, *3, *4, *5, *6, *7, *9, *10, *14, *17, *29, *41, *45, *46, and gene diversity (GD) alleles using validated genotyping methods.27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33 Subjects who carried 2 of the mutant alleles *3, *4, *5, *6, and *7 were considered poor metabolizers. Subjects who carried 1 mutant allele and 1 reduced‐activity allele (*9, *10, *17, *29, *41, *45, or *46) or 1 mutant allele and 1 functional allele (wild‐type [WT] or *2), or 2 reduced‐activity alleles were considered intermediate metabolizers. Subjects with the following alleles were classified as extensive metabolizers: *10/WT, *17/GD, *17/WT, *2/*10, *2/*17, *2/*2, *2/*29, *2/*41, *2/*45, *2/*9, *2/WT, *29/WT, *4/GD, *41/WT, *46/GD, *5/GD, *6/GD, *9/WT or WT/WT. Subjects with at least 3 copies of a functional allele were ultrarapid metabolizers.

Methadone

Following screening (day –28 to day –2), subjects checked in at the study center (day –1), where they remained intermittently until day 29. A follow‐up visit was conducted at the study center on day 36 (±2 days).

Subjects received a single oral dose of methadone hydrochloride 10 mg on day 1, followed by a washout period (Figure 1D). On days 16 and 17, subjects received oral isavuconazole 200 mg TID (8 hours apart), then 200 mg QD on days 18 to 28. An additional single oral dose of methadone hydrochloride 10 mg was coadministered with isavuconazole on day 20. Subjects fasted for ≥10 hours prior to administration of methadone on days 1 and 20 and dosing of isavuconazole on day 19 and continued to fast for 4 hours after administration. On day 20, isavuconazole was administered immediately before methadone hydrochloride.

Blood samples were drawn for PK analysis of R‐ and S‐methadone at predose on days 1 and 20 and at 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, 12, 16, 20, 24, 48, 72, 96, 120, 144, 168, 192, and 216 hours postdose. Additional samples were taken for PK analysis of isavuconazole on days 19 and 20 at predose and at 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, 12, 16, 20, and 24 hours postdose.

Pharmacokinetic Assessments

Plasma concentrations of all analytes were measured using validated liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry methods. The method for bioanalysis of isavuconazole is described in an accompanying paper.13 Details for bioanalysis of all other analytes are provided in the Methods section of Supplementary Materials. The primary parameters calculated for each of the substrate probes under investigation and their metabolites were area under the concentration‐time curve (AUC) from time 0 to infinity (AUC∞), AUC from time of dosing to time of last measurable concentration (AUClast), and maximum drug concentration (Cmax). Secondary variables included AUC for a dosing interval (AUCτ; isavuconazole only), time to Cmax (tmax), elimination half‐life (t1/2), volume of distribution (Vz/F), and clearance (CL/F).

The PK of both R‐ and S‐enantiomers of methadone was assessed. Dextromethorphan and dextrorphan PK parameters were also calculated for the overall trial population and for groups subdivided according to their CYP2D6 metabolizer status (ie, intermediate or extensive).

Safety Assessments

Safety and tolerability were examined by monitoring treatment‐emergent adverse events (TEAEs), vital‐sign measurements, 12‐lead electrocardiograms, clinical laboratory testing (hematology, chemistry, and urinalysis), and physical examinations.

Statistics

Baseline demographics, clinical characteristics, and TEAEs were summarized using descriptive statistics for all patients who received ≥1 dose of study drug. Pharmacokinetics were assessed in all subjects who received ≥1 dose of study drug and whose PK data were adequate for the calculation of ≥1 of the primary PK parameters. Levels of analyte below the level of quantification were entered as 0 for calculations.

Noncompartmental analyses were conducted with Phoenix® WinNonlin® version 5.2.1 or higher (Pharsight Corp, Mountain View, California). All data processing, summarization, and analyses were conducted using SAS® version 9.1 or higher (Statistical Analysis Software, Cary, North Carolina).

To assess the effect of isavuconazole on the PK of each substrate probe and metabolite, log‐transformed AUC and Cmax values were analyzed using a linear mixed‐effects model, with treatment as a fixed effect and subject as a random effect. For dextromethorphan and dextrorphan, the model also included CYP2D6 predicted phenotype as a fixed effect. The 90% confidence intervals (CIs) were constructed around the geometric least‐squares mean ratio of PK parameters measured during dosing with the substrate probe plus isavuconazole vs dosing with the substrate probe alone.

Results

Pharmacokinetics

Bupropion

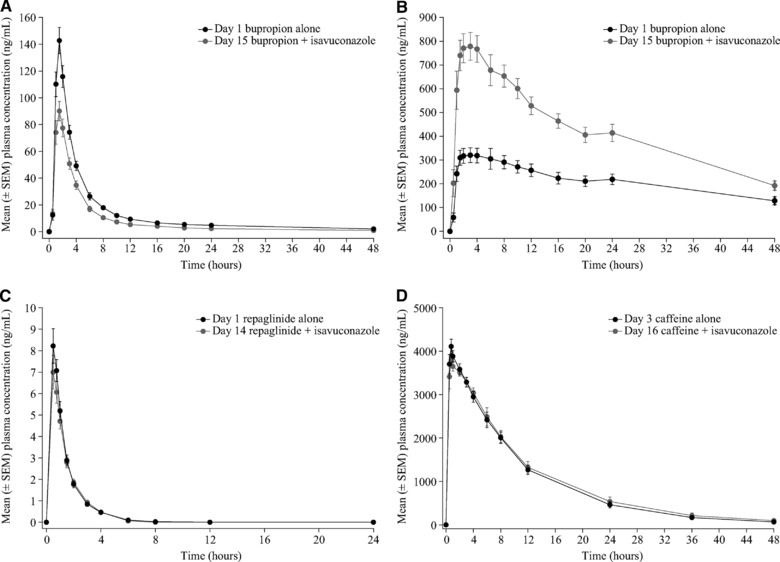

In total, 24 subjects enrolled in and completed the bupropion study (Table S1). Coadministration with isavuconazole decreased mean plasma AUC∞, AUClast, and Cmax of bupropion by 30% to 40% (Figure 2A, Tables 1 and 2) and resulted in a corresponding increase of these parameters for the hydroxybuproprion metabolite (Figure 2B, Tables S2, S3). The mean plasma AUCτ, Cmax, and median tmax of isavuconazole were similar in the presence and absence of bupropion compared with isavuconazole alone (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Mean plasma concentration‐time profiles of bupropion (A), hydroxybupropion (B), repaglinide (C), and caffeine (D) in the presence and absence of isavuconazole. EM, extensive metabolizer; IM, intermediate metabolizer; SEM, standard error of the mean.

Table 1.

Summary of Plasma Pharmacokinetic Parameters of CYP Substrate Probes in the Presence and Absence of Isavuconazole

| Bupropion | Repaglinide | Caffeine | Dextromethorphan | R‐methadone | S‐methadone | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parametera | Bupropion Alone (n = 24) | Bupropion + Isavuconazole (n = 24) | Repaglinide Alone (n = 24) | Repaglinide + Isavucoazole (n = 22)b | Caffeine Alone (n = 24) | Caffeine + Isavuconazole (n = 22)b | Dextromethorphan Alone (n = 24) | Dextromethorphan + Isavuconazole (n = 23)c | Methadone Alone (n = 23) | Methadone + Isavuconazole (n = 22)d | Methadone Alone (n = 23) | Methadone + Isavuconazole (n = 22)d |

| AUC∞, ng.h/mL | 715.7 (216.2) | 425.9 (157.5) | 11.4 (4.8) | 10.5 (3.9) | 44,896 (18,982) | 47,724 (24,410) | 45.7 (54.8)e | 54.4 (64.5)e | 557.1 (184.6) | 500.5 (166.7) | 739.2 (304.6) | 500.2 (254.2) |

| AUClast, ng.h/mL | 684.9 (205.8) | 406.2 (155.0) | 10.8 (4.7) | 9.9 (3.8) | 43,367 (16,463) | 45,581 (20,208) | 40.3 (53.2) | 48.6 (62.6) | 519.9 (158.7) | 476.9 (145.8) | 714.9 (285.0) | 491.9 (247.9) |

| Cmax, ng/mL | 148.6 (49.1) | 102.5 (33.7) | 8.7 (3.6) | 7.6 (3.2) | 4319 (745) | 4256 (651) | 3.9 (4.3) | 4.6 (5.1) | 12.7 (3.6) | 13.1 (3.7) | 22.0 (6.9) | 22.1 (7.3) |

| tmax, hours | 1.5 (1.0‐2.0) | 1.5 (1.0‐2.0) | 0.5 (0.5‐1.0) | 0.5 (0.5‐1.5) | 0.8 (0.5‐2.0) | 0.8 (0.5‐3.0) | 3.0 (1.5‐5.0) | 3.0 (1.5‐5.0) | 4.0 (2.0‐6.0) | 3.0 (2.0‐8.0) | 3.0 (1.5‐4.0) | 2.5 (1.0‐6.0) |

| t1/2, hours | 25.0 (7.5) | 19.2 (7.2) | 1.1 (0.4) | 1.0 (0.2) | 6.9 (3.1) | 7.4 (3.7) | 8.2 (3.6)f | 8.0 (2.8)g | 53.0 (14.0) | 42.1 (14.4) | 39.2 (12.0) | 23.6 (10.0) |

| CL/F, L/h | 151.9 (44.2) | 271.1 (107.3) | 54.0 (27.6) | 54.9 (23.0) | 5.2 (2.3) | 5.1 (2.1) | 3952 (8034)e | 2084 (2165)e | 10.1 (3.8) | 11.2 (4.2) | 8.3 (4.6) | 13.2 (7.5) |

AUC, area under the concentration‐time curve; CL/F, clearance; Cmax, maximum concentration; ISAV, isavuconazole; ND, not done; tmax, time to maximum concentration; t½, terminal half‐life; TEAE, treatment‐emergent adverse event.

AUC∞, AUClast, CL/F, Cmax, t½, and Vz/F values are mean (standard deviation); tmax is median (range).

Two subjects discontinued on day 13 due to TEAEs.

One subject discontinued on day 8 due to TEAEs.

One subject discontinued on day 5 due to a TEAE.

Values for 2 subjects were excluded from calculation as unreliable because the percentage of area extrapolated in the calculation of AUC∞ exceeded 20%.

Values for 2 subjects were excluded from calculation because concentration was below the lower limit of quantification in the terminal phase, thereby precluding calculation of terminal half‐life.

Values for 1 subject was excluded from calculation because concentration was below the lower limit of quantification in the terminal phase, thereby precluding calculation of terminal half‐life.

Table 2.

Statistical Analysis of the Effect of Isavuconazole on the Plasma Pharmacokinetics of CYP Substrate Probes and Their Metabolitesa

| Geometric Least‐Squares Mean Ratio, % (90%CI)b | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Bupropion | Repaglinide | Caffeine | Dextromethorphan | R‐Methadone | S‐Methadone |

| AUC∞ | 58 (52, 64) | 92 (86, 100) | 104 (97, 112) | 118 (102, 135) | 90 (84, 96) | 65 (59, 72) |

| AUClast | 57 (52, 64) | 91 (85, 97) | 104 (97, 111) | 123 (106, 142) | 92 (86, 97) | 66 (59, 73) |

| Cmax | 69 (62, 77) | 86 (79, 93) | 99 (93, 107) | 117 (102, 135) | 104 (97, 111) | 101 (95, 108) |

AUC, area under the concentration‐time curve; CI, confidence interval; Cmax, maximum concentration.

Results are based on a model of natural log–transformed parameters with treatment as a fixed effect (predicted phenotype also a fixed effect for dextromethorphan) and subject as a random effect.

(CYP substrate probe + isavuconazole)/CYP substrate probe alone.

Table 3.

Summary of Plasma Pharmacokinetic Parameters for Isavuconazole

| Bupropion | Repaglinide/Caffeine | Dextromethorphan | Methadone | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parametera | ISAV Alone (n = 24) | ISAV + Bupropion (n = 24) | ISAV Alone (n = 24) | ISAV + Repaglinide (n = 22)b | ISAV + Caffeine (n = 22)b | ISAV Alone (n = 24) | ISAV + Dextromethorphan (n = 23)c | ISAV Alone (n = 22)d | ISAV + Methadone (n = 22)d |

| AUCτ, μg.h/mL | 94.3 (13.1) | 93.3 (14.8) | 122.9 (29.6) | 123.2 (26.6) | 131.6 (28.9) | 92.4 (36.1) | 95.6 (38.0) | 99.5 (44.1) | 102.6 (46.3) |

| Cmax, μg/mL | 6.20 (1.00) | 6.32 (1.18) | 7.33 (1.51) | 7.44 (1.59) | 7.98 (1.72) | 5.82 (1.8) | 6.3 (1.9) | 6.8 (3.0) | 6.6 (2.7) |

| tmax, hours | 3.0 (1.5‐4.0) | 3.0 (1.5‐4.0) | 3.0 (2.0‐4.0) | 3.0 (1.5‐4.2) | 3.0 (2.0‐4.0) | 3.0 (1.5‐5.1) | 2.0 (1.2‐4.3) | 3.0 (2.0‐4.0) | 3.0 (1.5‐4.0) |

AUC, area under the concentration‐time curve; Cmax, maximum concentration; ISAV, isavuconazole; TEAE, treatment‐emergent adverse event; tmax, time to maximum concentration.

AUCτ and Cmax values are mean (standard deviation); tmax is median (range).

Two subjects discontinued on day 13 due to TEAEs.

One subject discontinued on day 8 due to TEAEs.

One subject discontinued on day 5 due to a TEAE.

Repaglinide and Caffeine

Twenty‐four subjects enrolled in the repaglinide and caffeine study, and 22 subjects completed the study (Table S1). Repaglinide exposure (AUC∞ and AUClast) and Cmax were slightly lower (∼8% to 14%) in the presence vs absence of isavuconazole, whereas exposure and Cmax for caffeine were comparable in the presence and absence of isavuconazole (Figure 2C, D; Tables 1 and 2). Coadministration with either repaglinide or caffeine did not affect the AUCτ, Cmax, or tmax of isavuconazole (Table 3).

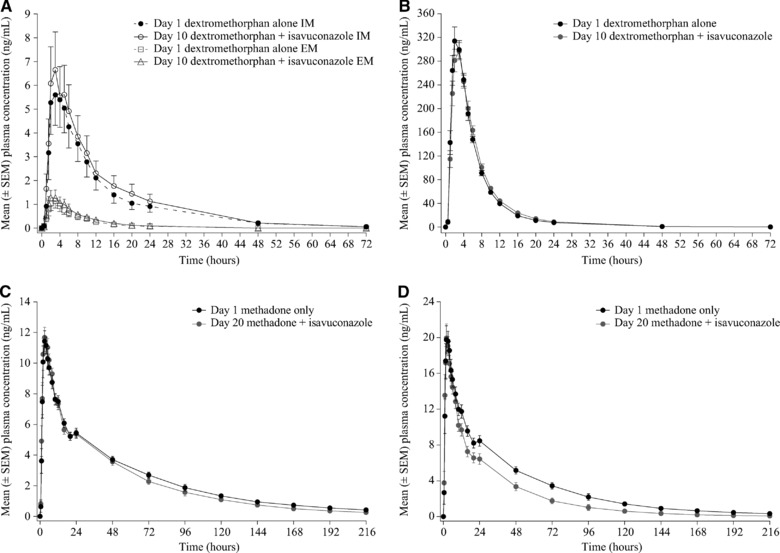

Dextromethorphan

A total of 24 subjects enrolled in this study, and 23 subjects completed the study (Table S1). Mean plasma AUC∞, AUClast, and Cmax of dextromethorphan were increased by approximately 20% by coadministration of isavuconazole (Tables 1 and 2). Of those who completed, 12 subjects were classified as intermediate metabolizers, and 11 were classified as extensive metabolizers. The relative change in dextromethorphan exposure with coadministered isavuconazole was similar for both intermediate and extensive metabolizers (Figure 3A; data not shown). There were no clinically relevant changes to the PK of dextrorphan (Figure 3B, Tables S2 and S3; data not shown). The PK parameters of isavuconazole were unaffected by the presence of dextromethorphan and dextrorphan (Table 3) regardless of CYP2D6 genotype (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Mean plasma concentration‐time profiles of dextromethorphan (A), dextrorphan (B), R‐methadone (C), and S‐methadone (D) in the presence and absence of isavuconazole. SEM, standard error of the mean.

Methadone

Twenty‐three subjects enrolled, and 22 subjects completed the methadone study (Table S1). Mean plasma AUC∞ and AUClast of R‐methadone were decreased approximately 10% in the presence vs absence of isavuconazole, whereas the Cmax was slightly increased (Figure 3C; Tables 1 and 2). However, coadministration of isavuconazole resulted in a decrease in the exposure of S‐methadone by approximately 35%, and the Cmax was increased by 1% (Figure 3D; Tables 1 and 2). The PK parameters of isavuconazole were similar in the presence and absence of methadone (Table 3).

Safety

Among all studies, there were no deaths, 1 serious TEAE, and discontinuations due to TEAEs were rare (Table 4). In the bupropion study the incidence of TEAEs was low, and TEAEs experienced by ≥1 subject included rhinitis (n = 2) and headache (n = 2) (Table S4).

Table 4.

Treatment‐Emergent Adverse Events

| Bupropion | Caffeine and Repaglinide | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Safety, n (%) | Bupropion Alone (n = 24) | ISAV Alone (n = 24) | Bupropion + ISAV (n = 24) | Repaglinide Alone (n = 24) | Caffeine Alone (n = 24) | ISAV Alone (n = 24) | Repaglinide + ISAV (n = 22)a | Caffeine + ISAV (n = 22)a |

| Any TEAE | 1 (4.2) | 2 (8.3) | 2 (8.3) | 1 (4.2) | 0 | 5 (20.8) | 2 (9.1) | 3 (13.6) |

| Drug‐related TEAE | 0 | 2 (8.3) | 2 (8.3) | 1 (4.2) | 0 | 3 (12.5) | 2 (9.1) | 2 (9.1) |

| Serious TEAE | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| TEAE leading to discontinuation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (8.3) | 0 | 0 |

| Deaths | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dextromethorphan | Methadone | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Safety, n (%) | Dextromethorphan Alone (n = 24) | ISAV Alone (n = 24) | Dextromethorphan + ISAV (n = 23)b | Methadone Alone (n = 23) | ISAV Alone (n = 22)c | Methadone + ISAV (n = 22)c | ||

| TEAE | 1 (4.2) | 11 (45.8) | 9 (39.1) | 16 (69.6) | 7 (31.8) | 12 (54.5) | ||

| Drug‐related TEAE | 1 (4.2) | 8 (33.3) | 6 (26.1) | 14 (60.9) | 4 (18.2) | 10 (45.5) | ||

| Serious TEAE | 0 | 1 (4.2)d | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| TEAE leading to discontinuation | 0 | 1 (4.2) | 0 | 1 (4.3) | 0 | 0 | ||

| Deaths | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

ISAV, isavuconazole; TEAE, treatment‐emergent adverse event.

Two subjects discontinued on day 13 due to TEAEs.

One subject discontinued on day 8 due to TEAEs.

One subject discontinued on day 5 due to a TEAE.

Perioral numbness and numbness of the right arm and leg.

In the study of caffeine and repaglinide the most common TEAEs were dizziness (n = 2), headache (n = 2), and palpitations (n = 2) (Table S5). No other TEAEs were experienced by ≥1 subject. One subject experienced TEAEs of hypoesthesia, feeling drunk, memory impairment, dysgeusia, dizziness, and balance disorder, which were considered by the study investigator as probably related to isavuconazole administration. The other subject experienced TEAEs of insomnia, noncardiac chest pain, anxiety, and abnormal ECG T‐wave, which were not considered related to isavuconazole administration. TEAEs in both subjects resolved fully following discontinuation of the study drug.

In the dextromethorphan study the most common TEAEs were somnolence (n = 4) and diarrhea (n = 4) (Table S6). One subject discontinued the study on day 8 during treatment with isavuconazole alone due to serious TEAEs of perioral numbness and numbness of the right arm and leg. Both events were considered by the study investigator as probably related to isavuconazole treatment and resolved fully by day 9.

In the methadone study the most common TEAEs were nausea (n = 10), vomiting (n = 8), and decreased appetite (n = 5) (Table S7). One subject discontinued the study during methadone administration on day 5 due to a moderate TEAE of toothache. This TEAE was not considered to be related to methadone and resolved fully following discontinuation from the study.

Discussion

This series of phase 1 studies was conducted to evaluate the PK effects of isavuconazole coadministration with the CYP substrate probes bupropion (CYP2B6), repaglinide (CYP2C8), caffeine (CYP1A2), dextromethorphan (CYP2D6 and CYP3A4), and methadone (CYP2B6, CYP2C19, and CYP3A4). Coadministration with isavuconazole was associated with an approximate 42% decrease in bupropion exposure, an 18% increase in dextromethorphan exposure, and a 35% decrease in S‐methadone exposure. By contrast, isavuconazole coadministration had little effect on the exposure to caffeine, repaglinide, and R‐methadone (<15% change in AUC or Cmax for each). These findings indicate that isavuconazole is a mild inducer of CYP2B6 but does not affect the metabolic activities of CYP1A2, CYP2C8, CYP2D6, or CYP2C19 (see also below).

Although isavuconazole decreased exposure to bupropion (a CYP2B6 substrate), the decrease in exposure to methadone, also a CYP2B6 substrate, was stereoselective. Multiple doses of isavuconazole decreased R‐methadone exposure by 10% and S‐methadone by 30%. Methadone is N‐demethylated to 2‐ethylidene‐1,5‐dimethyl‐3,3‐diphenylpyrrolidine (EDDP) by CYP2B6 and CYP3A4 in vitro but by CYP2B6 in vivo.18 This evidence is consistent with the idea that CYP3A4 has little effect on the disposition, metabolism, and clearance of methadone in vivo19, 20, 21, 22, 23 and the observation that CYP2B6 and CYP2C19 are known to have stereoselective effects on methadone metabolism, as CYP2B6 preferentially metabolizes S‐methadone, whereas CYP2C19 preferentially metabolizes R‐methadone.24, 25, 26 Thus, our results are consistent with the idea that the effects of isavuconazole coadministration on methadone PK are attributable entirely to effects on these isoenzymes, including mild induction of CYP2B6 and little or no effect on CYP2C19. The lack of an effect of isavuconazole is also supported by observations of a lack of any significant effect on the PK of omeprazole as well (data on file).

The PK of repaglinide is determined by its interactions not only with CYP isoenzymes but also with the organic anion‐transporting polypeptide 1B1 (OATP1B1).34, 35 However, isavuconazole does not affect OATP1B1 activity in vitro (data on file) or in vivo,11 and so the lack of an effect of isavuconazole on repaglinide exposure can be interpreted to reflect the lack of an effect of isavuconazole on CYP2C8.

The slight increase in dextromethorphan exposure (<20%) with multiple doses of coadministered isavuconazole observed in the current study most likely resulted from inhibition of CYP3A4. Although dextromethorphan is also metabolized by CYP2D6, that isoenzyme is subject to highly variable levels of activity according to allelic variations36; whereas we found that changes in dextromethorphan exposure were comparable in both CYP2D6 intermediate and extensive metabolizers. Thus, isavuconazole is unlikely to have any clinically relevant interactions with CYP2D6.

Few clinical trials have examined interactions between other currently approved triazole antifungal agents and the substrate probes evaluated in our studies. In contrast to isavuconazole, voriconazole is associated with up to 2‐fold increases in R‐methadone exposure, which are attributed to CYP3A4 inhibition37 (see also VFEND® package insert). Similar to isavuconazole, posaconazole does not inhibit CYP1A2, CYP2C8, or CYP2D6 activity.38 In addition, coadministration with ketoconazole causes only minor increases (∼15%) in repaglinide exposure.39 No studies have evaluated interactions between bupropion and the triazole antifungal agents.

The effects of isavuconazole on these various CYP isoenzymes in vivo differ in some key respects from effects observed in vitro for some other triazole antifungal agents. For example, induction of CYP2B6 by isavuconazole in vivo contrasts with inhibition of this isoenzyme observed in vitro for itraconazole40 and voriconazole.41 The lack of any apparent effect of isavuconazole on CYP1A2 in vivo also contrasts with the moderate inhibition of that isoenzyme by fluconazole observed in vitro.42 These differences also further underscore the limitations of extrapolating in vitro data to clinical practice because the labels for those agents do not indicate any significant effects of those agents on these isoenzymes in vivo.

Taken together, these findings support that isavuconazole is a moderate inhibitor of CYP3A4 and indicate that isavuconazole is a mild inducer of CYP2B6. Thus, appropriate precautions should be observed when coadministering other substrates of these isoenzymes. There was no indication that isavuconazole had any substantial effect on CYP1A2, CYP2C8, CYP2D6, or CYP2C19. Therefore, it is unlikely that substrates of these isoenzymes would be affected by isavuconazole administration. Finally, given the lack of any effect of these agents on the PK of isavuconazole, it is unlikely that any dose adjustment of isavuconazole would be required during coadministration with substrates of these isoenzymes.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

Isavuconazonium sulfate has been codeveloped by Astellas Pharma Global Development, Inc. and Basilea Pharmaceutica International Ltd. T.Y., A.D., C.H., S.A., D.K., C.L., H.P., and R.T. are employees of Astellas Pharma Global Development, Inc. R.G. and D.H. are employees of PAREXEL who were contracted to perform parts of the studies. D.R. is an in‐house contractor employed by Astellas Pharma Global Development, Inc.

Supporting information

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web‐site.

Acknowledgments

The studies were funded by Astellas Pharma Global Development, Inc. Editorial support was provided by Neil M. Thomas, PhD, and Ed Parr, PhD, medical writers at Envision Scientific Solutions, funded by Astellas Pharma Global Development, Inc. The authors wish to acknowledge Selina Moy of Astellas Pharma Global Development, Inc., for bioanalytical support. The authors are grateful for the contributions of the investigators and staff who conducted the clinical trials and to the subjects who volunteered for these studies.

References

- 1. Azie N, Neofytos D, Pfaller M, Meier‐Kriesche HU, Quan SP, Horn D. The PATH (Prospective Antifungal Therapy) Alliance® registry and invasive fungal infections: update 2012. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;73:293–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brown GD, Denning DW, Gow NA, Levitz SM, Netea MG, White TC. Hidden killers: human fungal infections. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:165rv113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dignani MC. Epidemiology of invasive fungal diseases on the basis of autopsy reports. F1000Prime Rep. 2014;6:81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rybak JM, Marx KR, Nishimoto AT, Rogers PD. Isavuconazole: pharmacology, pharmacodynamics, and current clinical experience with a new triazole antifungal agent. Pharmacotherapy. 2015;35:1037–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Miceli MH, Kauffman CA. Isavuconazole: a new broad‐spectrum triazole antifungal agent. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:1558–1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Alcazar‐Fuoli L, Mellado E. Ergosterol biosynthesis in Aspergillus fumigatus: its relevance as an antifungal target and role in antifungal drug resistance. Front Microbiol. 2012;3:439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Seyedmousavi S, Verweij PE, Mouton JW. Isavuconazole, a broad‐spectrum triazole for the treatment of systemic fungal diseases. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2015;13:9–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Maertens JA, Raad, II , Marr KA, et al. Isavuconazole versus voriconazole for primary treatment of invasive mould disease caused by Aspergillus and other filamentous fungi (SECURE): a phase 3, randomised‐controlled, non‐inferiority trial. Lancet. 2016;387:760–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Perfect J, Cornely O, Ostrosky‐Zeichner L, et al. Outcomes, safety, and tolerability of isavuconazole for the treatment of invasive fungal disease (phase 3 VITAL trial). Paper presented at: International Society for Human and Animal Mycology 2015 Congress; May 4‐8, 2015; Melbourne, Australia.

- 10. Marty FM, Ostrosky‐Zeichner L, Cornely OA, et al. Isavuconazole treatment for mucormycosis: a single‐arm open‐label trial and case‐control analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:828–837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yamazaki T, Desai A, Goldwater R, et al. Pharmacokinetic interactions between isavuconazole and the drug transporter substrates atorvastatin, digoxin, metformin, and methotrexate in healthy subjects. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev. 2017;6:66–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Groll AH, Desai A, Han D, et al. Pharmacokinetic assessment of drug‐drug interactions of isavuconazole with the immunosuppressants cyclosporine, mycophenolic acid, prednisolone, sirolimus, and tacrolimus in healthy adults. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev. 2017;6:76–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Townsend R, Dietz AJ, Hale C, et al. Pharmacokinetic evaluation of CYP3A4‐mediated drug‐drug interactions of isavuconazole with rifampin, ketoconazole, midazolam, and ethinyl estradiol/norethindrone in healthy adults. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev. 2017;6:44–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hesse LM, Venkatakrishnan K, Court MH, et al. CYP2B6 mediates the in vitro hydroxylation of bupropion: potential drug interactions with other antidepressants. Drug Metab Dispos. 2000;28:1176–1183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bidstrup TB, Bjørnsdottir I, Sidelmann UG, Thomsen MS, Hansen KT. CYP2C8 and CYP3A4 are the principal enzymes involved in the human in vitro biotransformation of the insulin secretagogue repaglinide. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;56:305–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Butler MA, Iwasaki M, Guengerich FP, Kadlubar FF. Human cytochrome P‐450PA (P‐450IA2), the phenacetin O‐deethylase, is primarily responsible for the hepatic 3‐demethylation of caffeine and N‐oxidation of carcinogenic arylamines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:7696–7700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ducharme J, Abdullah S, Wainer IW. Dextromethorphan as an in vivo probe for the simultaneous determination of CYP2D6 and CYP3A activity. J Chromatogr B Biomed Appl. 1996;678:113–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Campbell SD, Gadel S, Friedel C, Crafford A, Regina KJ, Kharasch ED. Influence of HIV antiretrovirals on methadone N‐demethylation and transport. Biochem Pharmacol. 2015;95:115–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kharasch ED, Bedynek PS, Hoffer C, Walker A, Whittington D. Lack of indinavir effects on methadone disposition despite inhibition of hepatic and intestinal cytochrome P4503A (CYP3A). Anesthesiology. 2012;116:432–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kharasch ED, Hoffer C, Whittington D, Sheffels P. Role of hepatic and intestinal cytochrome P450 3A and 2B6 in the metabolism, disposition, and miotic effects of methadone. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2004;76:250–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kharasch ED, Stubbert K. Cytochrome P4503A does not mediate the interaction between methadone and ritonavir‐lopinavir. Drug Metab Dispos. 2013;41:2166–2174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kharasch ED, Walker A, Whittington D, Hoffer C, Bedynek PS. Methadone metabolism and clearance are induced by nelfinavir despite inhibition of cytochrome P4503A (CYP3A) activity. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;101:158–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Greenblatt DJ. Drug interactions with methadone: Time to revise the product label. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev. 2014;3:249–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gerber JG, Rhodes RJ, Gal J. Stereoselective metabolism of methadone N‐demethylation by cytochrome P4502B6 and 2C19. Chirality. 2004;16:36–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Totah RA, Sheffels P, Roberts T, Whittington D, Thummel K, Kharasch ED. Role of CYP2B6 in stereoselective human methadone metabolism. Anesthesiology. 2008;108:363–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kharasch ED, Stubbert K. Role of cytochrome P4502B6 in methadone metabolism and clearance. J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;53:305–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Armstrong M, Fairbrother K, Idle JR, Daly AK. The cytochrome P450 CYP2D6 allelic variant CYP2D6J and related polymorphisms in a European population. Pharmacogenetics. 1994;4:73–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gaedigk A, Blum M, Gaedigk R, Eichelbaum M, Meyer UA. Deletion of the entire cytochrome P450 CYP2D6 gene as a cause of impaired drug metabolism in poor metabolizers of the debrisoquine/sparteine polymorphism. Am J Hum Genet. 1991;48:943–950. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Løvlie R, Daly AK, Molven A, Idle JR, Steen VM. Ultrarapid metabolizers of debrisoquine: characterization and PCR‐based detection of alleles with duplication of the CYP2D6 gene. FEBS Lett. 1996;392:30–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lundqvist E, Johansson I, Ingelman‐Sundberg M. Genetic mechanisms for duplication and multiduplication of the human CYP2D6 gene and methods for detection of duplicated CYP2D6 genes. Gene. 1999;226:327–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Masimirembwa C, Persson I, Bertilsson L, Hasler J, Ingelman‐Sundberg M. A novel mutant variant of the CYP2D6 gene (CYP2D6*17) common in a black African population: association with diminished debrisoquine hydroxylase activity. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1996;42:713–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Steen VM, Molven A, Aarskog NK, Gulbrandsen AK. Homologous unequal cross‐over involving a 2.8 kb direct repeat as a mechanism for the generation of allelic variants of human cytochrome P450 CYP2D6 gene. Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4:2251–2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Stüven T, Griese EU, Kroemer HK, Eichelbaum M, Zanger UM. Rapid detection of CYP2D6 null alleles by long distance‐ and multiplex‐polymerase chain reaction. Pharmacogenetics. 1996;6:417–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kalliokoski A, Niemi M. Impact of OATP transporters on pharmacokinetics. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;158:693–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Niemi M, Backman JT, Kajosaari LI, et al. Polymorphic organic anion transporting polypeptide 1B1 is a major determinant of repaglinide pharmacokinetics. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2005;77:468–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. van der Weide J, Steijns LS. Cytochrome P450 enzyme system: genetic polymorphisms and impact on clinical pharmacology. Ann Clin Biochem. 1999;36(Pt 6):722–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Liu P, Foster G, Labadie R, Somoza E, Sharma A. Pharmacokinetic interaction between voriconazole and methadone at steady state in patients on methadone therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:110–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wexler D, Courtney R, Richards W, Banfield C, Lim J, Laughlin M. Effect of posaconazole on cytochrome P450 enzymes: a randomized, open‐label, two‐way crossover study. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2004;21:645–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hatorp V, Hansen KT, Thomsen MS. Influence of drugs interacting with CYP3A4 on the pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and safety of the prandial glucose regulator repaglinide. J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;43:649–660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Walsky RL, Astuccio AV, Obach RS. Evaluation of 227 drugs for in vitro inhibition of cytochrome P450 2B6. J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;46:1426–1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jeong S, Nguyen PD, Desta Z. Comprehensive in vitro analysis of voriconazole inhibition of eight cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes: major effect on CYPs 2B6, 2C9, 2C19, and 3A. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:541–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lu C, Berg C, Prakash SR, Lee FW, Balani SK. Prediction of pharmacokinetic drug‐drug interactions using human hepatocyte suspension in plasma and cytochrome P450 phenotypic data. III. In vitro–in vivo correlation with fluconazole. Drug Metab Dispos. 2008;36:1261–1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web‐site.