Abstract

Venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA‐ECMO) is indicated in reversible life‐threatening circulatory failure with or without respiratory failure. Arterial desaturation in the upper body is frequently seen in patients with peripheral arterial cannulation and severe respiratory failure. The importance of venous cannula positioning was explored in a computer simulation model and a clinical case was described. A closed‐loop real‐time simulation model has been developed including vascular segments, the heart with valves and pericardium. ECMO was simulated with a fixed flow pump and a selection of clinically relevant venous cannulation sites. A clinical case with no tidal volumes due to pneumonia and an arterial saturation of below 60% in the right hand despite VA‐ECMO flow of 4 L/min was described. The case was compared with simulation data. Changing the venous cannulation site from the inferior to the superior caval vein increased arterial saturation in the right arm from below 60% to above 80% in the patient and from 64 to 81% in the simulation model without changing ECMO flow. The patient survived, was extubated and showed no signs of hypoxic damage. We conclude that venous drainage from the superior caval vein improves upper body arterial saturation during veno‐arterial ECMO as compared with drainage solely from the inferior caval vein in patients with respiratory failure. The results from the simulation model are in agreement with the clinical scenario.

Keywords: Dual circulations, Differential hypoxia, Harlequin syndrome, Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, Modeling, Simulation, Venoarterial, Cannulation

Extra corporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) is an established treatment for respiratory failure for over 20 years 1, 2. The CESAR‐trial suggests a beneficial outcome of adult ECMO patients when compared with conventional treatment in patients with respiratory failure 3. First choice of modality in respiratory failure without circulatory failure is veno venous ECMO (VV‐ECMO) and veno arterial ECMO (VA‐ECMO) should only be used in severe circulatory failure 4, 5. Respiratory pressures are usually reduced to minimize baro‐ and volutrauma to the lung 4, 6. These settings may result in partial or total collapse of the lungs and, therefore, low oxygen content in the blood entering the left side of the heart from the pulmonary veins 7, 8. VA‐ECMO is also commonly used as an emergency measure in cardiogenic shock 9. Left ventricular unloading during VA‐ECMO is often unsatisfactory 9, 10 and aggravation of pulmonary edema is, therefore, commonly seen 10. Peripheral arterial cannulation through one of the femoral arteries 9 is more common than central aortic cannulation 10, 11, 12, 13. Venous cannulation is usually through a femoral vein with the tip of the cannula in the inferior caval vein or lower part of the right atrium 9. Blood leaving the ECMO circuit is normally fully saturated with oxygen, but usually only reaches body regions supplied by the descending aorta and the distal aortic arch 14 in peripheral cannulation, as can be shown clinically when comparing pulse oximetry saturations 12, 15([12,15]; Fig. 1). Blood flow from the left ventricle continues to perfuse the coronary arteries and the aortic arch as shown in a recent experimental study 14. Left ventricular and arterial oxygen saturation in the upper body during VA‐ECMO with respiratory failure may, therefore, approach the saturation in the pulmonary artery with deoxygenated blood mainly originating from the superior caval vein, creating a clinical entity referred to as “dual circulation,” 15 “differential hypoxia,” 14 or “Harlequin syndrome” 16 in the literature. The upper body saturation is determined by venous drainage, cardiac preload, cardiac function, lung function and ECMO flow and may therefore vary over time.

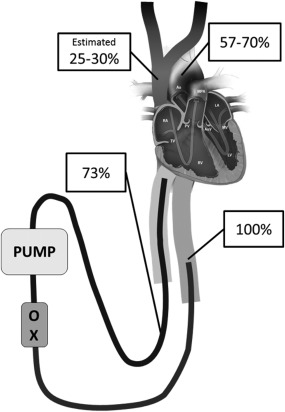

Figure 1.

Example of upper body deoxygenation during peripheral venoarterial ECMO in respiratory failure with total pulmonary collapse as in our clinical case. Saturation in the aortic arch was 57–70%. ECMO perfused the lower body with well oxygenated blood and inferior caval vein saturation and saturation in preoxygenator blood (73%) was therefore high. The venous saturation in the superior caval vein was estimated to be 25–30%.

Due to the critical condition of ECMO patients, experimental studies may be difficult to perform. Animal experiments 14 and simulation models may, therefore, be the best available tools when studying the complex physiology of these patients. The aim of this study was to explore the importance of venous cannula positions in regional oxygen delivery in a computer simulation model of VA‐ECMO. A clinical case with severe deoxygenation in the upper body during VA‐ECMO was compared with simulation data to illustrate the severity of the problem and relevance of the model.

PATIENT AND METHODS

Cardiovascular simulation model

A closed‐loop real‐time simulation model was developed consisting of 27 vascular segments, the four cardiac chambers with corresponding valves, septal interactions, the pericardium and intrathoracic pressure (Fig. 2) published elsewhere 17, 18. The cardiac chambers are represented as time‐varying elastances and the closed‐loop vascular system segments characterized by nonlinear resistances, compliances, inertias and visco‐elastances. Valves are opening and closing gradually depending on pressure gradients. No autonomic reflexes were included in the model.

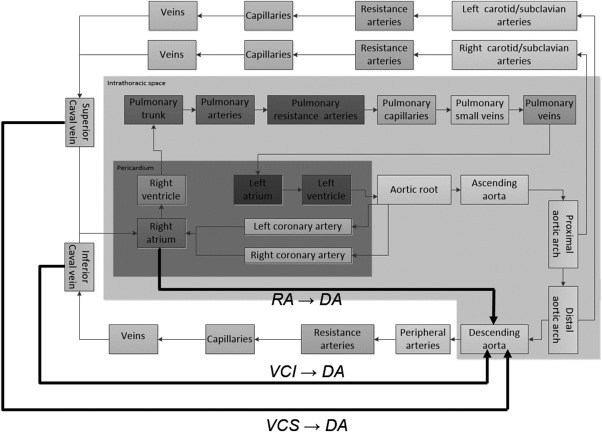

Figure 2.

The simulation model. The three different cannulation modes are shown with thick black lines. Vena cava superior to descending aorta (VCS → DA), right atrium to descending aorta (RA → DA) and vena cava inferior to descending aorta (VCI → DA).

The simulations were performed with normal cardiac function and an increase in pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) from 1.2 to 6.2 Wood units and a pulmonary shunt fraction of 100% mimicking a clinical VA‐ECMO patient with right heart dilatation due to increased PVR and a total pulmonary “white‐out” (no tidal volumes). Therefore, the oxygenator is the only source of oxygen to the patient. Intrathoracic pressure was set to zero to avoid variability due to circulatory changes during the respiratory cycle. Heart rate was set to 100 bpm.

ECMO simulation

ECMO flow was set at fixed flow 1 to 5 L/min with the cannulas in clinically relevant sites—(i) vena cava superior to descending aorta; (ii) right atrium to descending aorta; and (iii) vena cava inferior to descending aorta (Fig. 3). Postoxygenator saturation (S postox O2) was 100%. As ECMO flow was constant neither elastic nor inertial properties of the tubings were included in the simulation. The total length of tubing was identical in all simulations.

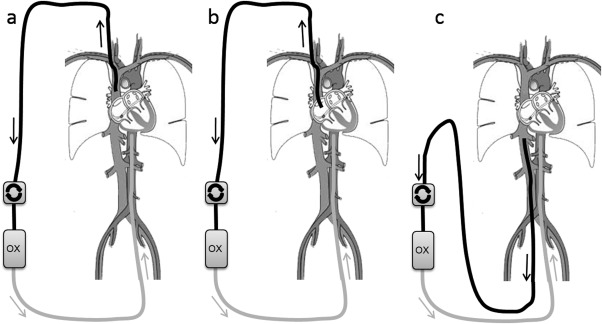

Figure 3.

Overview of cannulation: a) vena cava superior to descending aorta (VCS → DA), b) right atrium to descending aorta (RA → DA) and c) vena cava inferior to descending aorta (VCI → DA).

Oxygen transport

The oxygen carrying capacity of blood C (mL O2/L blood) was calculated according to Eq. (1) 19, where Hb is the hemoglobin level (g/L blood) and Sat is the oxygen saturation (%) of the vascular or cardiac compartment.

| (1) |

Dissolved oxygen was not taken into account. The oxygen saturation was considered homogenous in each compartment and exchange of oxygen between compartments proportional to flow. Hemoglobin was 110 g/L in simulations, corresponding to our institutional transfusion limit. Total oxygen consumption excluding the heart was set to 250 mL/min (3.6 mL/kg/min). Cardiac consumption was calculated according to Suga et al. 20 reaching a total of 278–283 mL/min. SvO2 is the mixed venous oxygen saturation (Fig. 4g), available in the simulation model as the flow‐weighted mean value of oxygen saturation in blood returning from the systemic capillaries, but differs substantially both from the preoxygenator saturation (Fig. 4h) and the pulmonary artery saturation, which are both dependent on the venous cannulation.

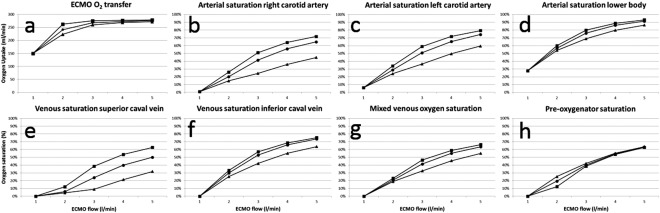

Figure 4.

Simulated oxygenation data. Veno‐arterial ECMO flow increased stepwise from 1 to 5 L/min with three different venous cannulation modes. ECMO oxygen transfer (a), arterial saturation in the right carotid (b), the left carotid (c), the lower body (d), the superior caval vein (e), the inferior caval vein (f), mixed venous blood (g) and preoxygenator saturation (h). ▪VCS → DA. •RA → DA. ▲ VCI → DA.

Clinical case

A 15‐year‐old female, with benign asthma, weighing 65 kg, was admitted due to breathlessness and hypoxia after a week of upper airway symptoms. She deteriorated with hypoxemia, high ventilator pressures, and circulatory instability and a decision to start VA‐ECMO was taken within 24 h. CRP was more than 400 mg/L and 4/4 blood cultures showed growth of Streptococcus pneumoniae. VA‐ECMO was chosen due to right heart failure caused by high PVR and left ventricular dysfunction as part of a septic shock syndrome. She was cannulated through the femoral vessels as an attempt through her jugular vein failed. She received one venous cannula in each femoral vein (21 Fr, 18 and 50 cm) and a femoral arterial cannula (17 Fr, 18 cm). Drainage flow in the short cannula in the femoral vein was higher than in the long, implying that most of the blood originated from the inferior caval vein. After the start of ECMO and lowering of ventilator pressures her lungs collapsed with zero tidal volumes. An arterial saturation of 57% was seen in the right hand despite VA‐ECMO flow of 4.2 L/min, preoxygenator saturation of 73% and arterial saturation in left arm of above 70% (Fig. 1). The higher left arm saturation can be explained by oxygenated blood from the ECMO system reaching the distal, but not the proximal aortic arch. The high preoxygenator saturation can be explained by the dominating drainage from the well oxygenated lower body illustrating the “dual circulations” concept 15. To improve oxygenation, the existing long femoral venous cannula was repositioned into the right atrium, resulting in an increase in right hand saturation by 5–10%. After a new successful jugular vein cannulation the short femoral venous cannula was removed and arterial saturation in the right hand ended above 80%. Oxygenation was in this situation considered adequate and the long femoral venous cannula was kept (for possible conversion to veno‐venous ECMO). Further increase in right hand saturation up to above 85% was seen when this cannula was temporarily clamped.

In the simulation of the case we used a pulmonary shunt fraction of 100%, a hemoglobin level of 114 g/L, an ECMO flow of 4.2 L/min, and an oxygen consumption of 170 mL/min corresponding to the values in the patient. Heart rate, cardiac function, and vascular resistances were set to create a hemodynamic state as close as possible to the real patient. The cardiovascular parameters were kept constant when simulating different cannulation modes as the patient was circulatory stable during these procedures.

Calculations

The program version used was Aplysia CardioVascular Lab 5.2.0.14 (Aplysia Medical AB, Stockholm, Sweden). All data were collected at end‐diastole at steady‐state conditions. Pressures, flows, volumes, and saturations were updated with 4000 Hz.

RESULTS

VA‐ECMO: Simulation of hemodynamics

Hemodynamics were almost identical at each ECMO flow between the three venous cannulation modes. Mean systemic arterial blood pressure was increasing from 82 to 121 mm Hg with ECMO flow increase from 1 to 5 L/min, while left ventricular output decreased from 4.3 to 3.9 L/min. Mean pulmonary artery and right atrial pressure decreased slightly, while left atrial pressure increased slightly with increasing ECMO flow.

VA‐ECMO: Simulation of oxygen transport

Total ECMO oxygen transfer (Fig. 4a) reached a plateau level close to the oxygen consumption of the patient at the 4–5 L/min flow in all cannulation modes. At flows 2–3 L/min the efficiency of oxygen transfer was highest with superior caval vein cannulation, intermediate with right atrium, and lowest with inferior caval vein. Oxygen transfer was identical at flow 1 L/min, as all venous saturations were 0% at this inappropriate flow, not compatible with survival.

Arterial saturations in the right carotid artery (Fig. 4b), left carotid artery (Fig. 4c), and the lower body (Fig. 4d) were highest with superior caval vein cannulation, intermediate with right atrium, and lowest with inferior caval vein at all flow rates. The difference was largest in the right carotid artery and less pronounced in the more distal arterial tree and increased with flow rate. Arterial differences were reflected in the venous saturations (Fig. 4e,f,g) with higher values with superior caval vein cannulation at all flows. Preoxygenator saturations (S preox O2, Fig. 4h) showed less differences between the cannulation modes, reflecting the variable mixture of less saturated superior caval vein blood and more saturated inferior caval vein blood. S preox O2 consistently overestimated mixed venous saturations in inferior caval vein cannulation.

Comparison with clinical case

Changing the position of one of the venous cannulas from the inferior caval vein to the right atrium, removing the short cannula draining the lower inferior caval vein and finally adding a cannula in the superior caval vein (21 Fr, 18 cm) increased arterial saturation in the right hand from 57% to above 80% in the patient. Mimicking the hemodynamics of the patient in the simulation model with unchanged ECMO blood flow of 4.2 L/min and various venous cannulation sites resulted in right hand arterial saturations of 64% (inferior caval vein), 75% (right atrium) to 81% (superior caval vein), respectively. The patient improved within a few days, was extubated and discharged to her home without signs of hypoxic damage within one week from decannulation, and is now back in school.

DISCUSSION

The main finding of our simulation study is that arterial saturations are highly dependent on the venous cannulation site during VA‐ECMO in patients with severe respiratory failure. Venous drainage from the superior caval vein should be preferred in VA‐ECMO if hypoxic respiratory failure is present in agreement with a recent experimental study 14 and our presented clinical case.

Preoxygenator saturation is an unpredictable measure of oxygenation

A previous study has shown that preoxygenator saturation (S preox O2) is an unreliable measure of treatment efficiency in VV‐ECMO 18. The venous saturations in the superior caval vein and inferior caval vein may differ as much as 25% or more in VA‐ECMO and S preox O2 is dependent on the relative contribution from these two sources. If highly saturated inferior caval vein blood is drained treatment efficiency decreases although the high S preox O2 may falsely give the impression of adequate oxygenation. In contrast drainage of superior caval vein blood improves oxygenation efficiency, but may result in a lower S preox O2. Measurement of saturations in multiple sites is crucial. The lowest arterial saturation is usually found in the right arm and the lowest venous value in the superior caval vein.

Cannulation

Neck cannulation of the internal jugular vein (Fig. 2a,b) is the most common venous access mode in the ELSO database 21, but arterial and venous access via the femoral route (Fig. 2c) is recommended in emergency situations with severe circulatory failure 9, as this is a well‐known procedure to surgeons and both vessels can be approached in the same surgical field. This strategy works well in cardiac surgery when aortic cross‐clamping is part of the continued plan enabling the extracorporeal circuit to provide oxygenated blood to the entire systemic circulation (except the coronary arteries). If, however, pulmonary function is bad and the left heart continues to eject deoxygenated blood, both arterial and venous saturations in the upper body will decrease substantially. Alternative solutions in this situation are to cannulate the ascending aorta via sternotomy 22, via the axillary 13, subclavian 11, or carotid 23 arteries to improve upper body saturation. These procedures are, however, more time‐consuming and carry a substantially higher risk of bleeding 24. The risk of cerebral embolization is considered lower with axillary/subclavian artery cannulation in cardiac surgery as these vessels usually are less atherosclerotic than the descending aorta, iliac, and femoral arteries 25. This knowledge is, however, difficult to translate to VA‐ECMO, where blood entering the lower part of aorta usually does not reach the carotid circulation 15 and embolization risks are not only related to cannulation, but also to formation of clots with partial heparinization. We, therefore, believe femoral cannulation carries a lower risk of cerebral embolization than axillary/subclavian during VA‐ECMO. This study suggests an agreement with our clinical experience that the disadvantages with femoral arterial cannulation concerning oxygenation can be compensated to a large extent if the superior caval vein is used for venous drainage. This can be achieved with a venous cannula inserted through the jugular vein with a high atrial tip position or a long and wide femoral venous cannula without side holes reaching the upper part of the right atrium. Multistage (multiple holes) femoral venous cannulas and double (superior caval vein + inferior caval vein) venous drainage should be avoided.

Hemodynamics

Left ventricular unloading is often suboptimal with VA‐ECMO 26. The cardiac unloading effect in real patients can be improved by systemic vasodilatation and a decrease in blood volume if venous drainage is good (not explored in this study). It should however be mentioned that systemic vasodilatation in severe respiratory failure may aggravate arterial desaturation as blood ejected by the left ventricle may be poorly oxygenated. The clinical preferences concerning vascular tone should therefore be based on the relative importance of left ventricular unloading and arterial oxygenation.

Limitations

Only oxygen bound to hemoglobin is considered in this study, while it has been shown clinically that dissolved oxygen is of importance for oxygen delivery when high levels of oxygen are provided to the patient in the ECMO circuit 27, 28. However, the effect of this simplification is too small to affect the conclusions drawn in this work, as the main reason for desaturation is that ECMO blood flow does not reach the anatomical target area, rather than a lack of blood oxygen content.

The detailed comparison between the clinical case and simulation data is difficult as the patient had two venous cannulas with variable flows depending on position, cannula length and dimension and simulation data are based on only one venous cannula. Furthermore, complete hemodynamic data for the patient was not available, but still the direction and magnitude of changes in the simulation data were in good agreement with the described patient and our clinical experience.

CONCLUSIONS

The simulations suggest that venous drainage from the superior caval vein improves upper body arterial oxygen saturation and oxygen transfer as compared to inferior caval vein drainage in venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation patients with a femoral arterial cannula and severe pulmonary failure. Furthermore, the preoxygenator saturation in the ECMO system must be interpreted cautiously, as it often overestimates the patient's mixed venous oxygen saturation. The agreement between simulated and clinical data supports the relevance of the simulation model.

Key messages

Venous drainage from superior caval vein should be preferred in peripheral VA‐ECMO.

Preoxygenator saturation is not a reliable measure of mixed venous saturation in VA‐ECMO.

Computer simulation is a valuable tool in analysis of ECMO physiology.

Authors' Contributions: Michael Broomé (MB) constructed the model, performed programming, simulation runs and drafted the manuscript. Mattias Lindfors (ML) collected and analyzed the clinical patient material and drafted parts of the manuscript. AB participated in model construction and adaptation of the model to engineering standards as well as in manuscript drafting. BF drafted the manuscript. MB, ML, and BF all participated in evaluation of the clinical relevance of the model as being clinically active medical doctors taking care of ECMO patients. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interests: Michael Broomé is the founder and owner of the company Aplysia Medical AB developing the simulation software Aplysia CardioVascular Lab. There are no other conflicts of interest.

Consent to Publish: The patient and her parents in our reported case have approved publication of patient data.

Acknowledgment

Michael Broomé's research during the years 2013‐2015 was funded by The Swedish Research Council Grant 2012‐2800.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bartlett RH. Extracorporeal life support: history and new directions. ASAIO J 2005;51:487–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Conrad SA, Rycus PT, Dalton H. Extracorporeal life support registry report 2004. ASAIO J 2005;51:4–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Peek GJ, Mugford M, Tiruvoipati R, et al. Efficacy and economic assessment of conventional ventilatory support versus extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe adult respiratory failure (CESAR): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2009;374:1351–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Marasco SF, Lukas G, McDonald M, McMillan J, Ihle B. Review of ECMO (extra corporeal membrane oxygenation) support in critically ill adult patients. Heart Lung Circ 2008;17(Suppl. 4):S41–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Park PK, Napolitano LM, Bartlett RH. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in adult acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Clin 2011;27:627–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Marhong JD, Telesnicki T, Munshi L, Del Sorbo L, Detsky M, Fan E. Mechanical ventilation during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. An international survey. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2014;11:956–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Combes A, Bacchetta M, Brodie D, Muller T, Pellegrino V. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for respiratory failure in adults. Curr Opin Crit Care 2012;18:99–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Barnacle AM, Smith LC, Hiorns MP. The role of imaging during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in pediatric respiratory failure. Ajr Am J of Roentgenol 2006;186:58–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Westaby S, Anastasiadis K, Wieselthaler GM. Cardiogenic shock in ACS. Part 2: role of mechanical circulatory support. Nat Rev Cardiol 2012;9:195–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cheng A, Swartz MF, Massey HT. Impella to unload the left ventricle during peripheral extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. ASAIO J 2013;59:533–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Javidfar J, Brodie D, Costa J, et al. Subclavian artery cannulation for venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. ASAIO J 2012;58:494–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Avgerinos DV, DeBois W, Voevidko L, Salemi A. Regional variation in arterial saturation and oxygen delivery during venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Extra Corpor Technol 2013;45:183–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schachner T, Nagiller J, Zimmer A, Laufer G, Bonatti J. Technical problems and complications of axillary artery cannulation. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2005;27:634–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hou X, Yang X, Du Z, et al. Superior vena cava drainage improves upper body oxygenation during veno‐arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in sheep. Crit Care 2015;19:68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Alwardt CM, Patel BM, Lowell A, Dobberpuhl J, Riley JB, DeValeria PA. Regional perfusion during venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: a case report and educational modules on the concept of dual circulations. J Extra Corpor Technol 2013;45:187–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Moisan M, Lafargue M, Calderon J, Oses P, Ouattara A. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis requiring “hybrid” extracorporeal life support, and complicated by acute necrotizing pneumonia. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim 2013;32:e71–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Broome M, Maksuti E, Bjallmark A, Frenckner B, Janerot‐Sjoberg B. Closed‐loop real‐time simulation model of hemodynamics and oxygen transport in the cardiovascular system. Biomed Eng Online 2013;12:69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Broman M, Frenckner B, Bjallmark A, Broome M. Recirculation during veno‐venous extra‐corporeal membrane oxygenation—a simulation study. Int J Artif Organs 2015;38:23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hüfner CG. Neue versuche zur bestimmung der sauerstoffcapacitat der blutfarbstoffs. Arch Physiol 1902;17:130–76. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Suga H. Total mechanical energy of a ventricle model and cardiac oxygen consumption. Am J Physiol 1979;236:H498–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brogan TV, Thiagarajan RR, Rycus PT, Bartlett RH, Bratton SL. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in adults with severe respiratory failure: a multi‐center database. Intensive Care Med 2009;35:2105–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Maclaren G, Butt W, Best D, Donath S, Taylor A. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for refractory septic shock in children: one institution's experience. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2007;8:447–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rollins MD, Hubbard A, Zabrocki L, Barnhart DC, Bratton SL. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation cannulation trends for pediatric respiratory failure and central nervous system injury. J Pediatr Surg 2012;47:68–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Saeed D, Stosik H, Islamovic M, et al. Femoro‐femoral versus atrio‐aortic extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: selecting the ideal cannulation technique. Artif Organs 2014;38:549–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sabik JF, Lytle BW, McCarthy PM, Cosgrove DM. Axillary artery: an alternative site of arterial cannulation for patients with extensive aortic and peripheral vascular disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1995;109:885–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ostadal P, Mlcek M, Kruger A, et al. Increasing venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation flow negatively affects left ventricular performance in a porcine model of cardiogenic shock. J Transl Med 2015;13:266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Walker JL, Gelfond J, Zarzabal LA, Darling E. Calculating mixed venous saturation during veno‐venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Perfusion 2009;24:333–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lindstrom SJ, Mennen MT, Rosenfeldt FL, Salamonsen RF. Quantifying recirculation in extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: a new technique validated. Int J Artif Organs 2009;32:857–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]