Abstract

A better understanding of why medication errors (MEs) occur will mean that we can work proactively to minimise them. This study developed a proactive tool to identify general failure types (GFTs) in the process of managing cytotoxic drugs in healthcare. The tool is based on Reason's Tripod Delta tool. The GFTs and active failures were identified in 60 cases of MEs reported to the Swedish national authorities. The most frequently encountered GFTs were defences, procedures, organisation and design. Working conditions were often the common denominator underlying the MEs. Among the active failures identified, a majority were classified as slips, one‐third as mistakes, and for a few no active failure or error could be determined. It was found that the tool facilitated the qualitative understanding of how the organisational weaknesses and local characteristics influence the risks. It is recommended that the tool be used regularly. We propose further development of the GFT tool. We also propose a tool to be further developed into a proactive self‐evaluation tool that would work as a complement to already incident reporting and event and risk analyses.

Keywords: medication error, chemotherapy, proactive tool, resilience, organisational weaknesses, local characteristics

Introduction

Medications are of considerable help if healthcare providers are able to administer them to patients safely and appropriately. Yet, healthcare providers are humans and, and as such, fallible.

Adverse events in hospitals can constitute serious problems leading to grave consequences for patient safety. In a systematic review (De Vries et al. 2008) of the incidence and nature of in‐hospital adverse events, it was found that they affect nearly 1 of 10 patients. Operation‐ and medication‐related events constituted the majority of these. About the same figure was found in a Swedish study (Soop et al. 2009). Prescribing errors are common, but not all of them cause harm. A systematic review showed a median prescribing error rate of 7% of medication orders (Lewis et al. 2009). In another systematic review (Berdot et al. 2013), drug administration errors in hospital inpatients were detected by using observations. The median error rate, excluding wrong time errors, was 10.5%. Non‐fatal errors were observed and most errors were classified as minor. However, when it comes to chemotherapy, the situation is different. Cytotoxic drugs have high toxicity and a narrow therapeutic index, which means that there is little difference between a lethal and therapeutic dose. The use of such drugs may increase risks for the patient, as reported in the review article by Schwappach and Wernli (2010). In a study of medication safety in an ambulatory chemotherapy setting, the medication error (ME) rate was 3% and approximately one‐third were potentially serious (Gandhi et al. 2005). In Zernikow et al. (1999), fatal outcomes from cytotoxic drugs were described and analysed and they concluded that ‘complex interdependencies of contributing factors are the rule’.

According to Reason (1997), human beings contribute to the breakdown of a complex system, to an adverse event or to an accident waiting to happen in two main ways: (1) by an active failure, which is needed for the accident (or incident) to happen; (2) by latent conditions that are present within a system well before the onset of an adverse event or accident. Active failures are committed by the operator, when he or she is actually carrying out a task. Active failures are detected almost immediately and usually have immediate consequences. Latent conditions arise from strategic and other top‐level decisions made by regulators, manufacturers, designers and organisational managers (e.g. insufficient introduction of new staff and bad design of equipment).

An active failure can be defined as a failure of planned actions to achieve the desired goal. Active failures are sometimes referred to as errors at the ‘sharp end’. If the plan is adequate, but the associated actions do not go as intended, this results in failures of execution that are called ‘slips’ and ‘lapses’. Examples can be picking the wrong medication or strength from the shelf or transcribing a prescribed dose incorrectly. If, on the other hand, the action may go entirely as planned, but the plan is inadequate to achieve its intended outcome, these are considered failures of intention, referred to as ‘mistakes’ (Reason 1995). An example is the misjudgement of a patient's condition (i.e. the patient suffers adverse reactions due to an overdose of a medication or a miscalculation of a dose for prescription or preparation).

Reason's model of accident causation has been used as a framework to categorise and present data on errors. Dean et al. (2002) and Tully et al. (2009) used it in prescribing errors for hospital inpatients, and Keers et al. (2013) used it concerning medication administration errors in hospitals. For prescribing errors, the active failure most frequently cited was a mistake due to inadequate knowledge of the drug or the patient. Slips and lapses were also common. Latent conditions included reluctance to question senior colleagues and inadequate training. The most commonly reported unsafe acts for medication administering errors were slips and lapses. Among the error‐producing conditions were inadequate written communication, problems with the supply and storage of medicines, and high perceived workload. The authors concluded that these kinds of errors are influenced by multiple systems factors, with several active failures and error‐producing latent conditions often acting together.

Proactive improvement of the chemotherapy process

Suggestions have been made on ways to improve the chemotherapy process (prescription by doctors, preparation by pharmacists or nurses and administration by nurses). Examples of improvements are to apply an interdisciplinary approach, where the different professionals involved work together (Branowicki et al. 2003; Dinning et al. 2005) or to make use of computerised physician (or prescriber) order entry systems (Greenberg et al. 2006; Voeffray et al. 2006; Nerich et al. 2010). Even when improvements have been made, though, there is still a need to find proactive methods to identify risks and manage them before an accident happens.

One cornerstone of patient safety is learning from reported incidents and accidents. For incidents, the learning and countermeasures should take place locally at the healthcare provider. For accidents, often reported on a national level, learning should also take place at national and international levels. The learning can be presented in different ways, such as in journals that highlight interesting accidents as case reports, or as aggregated and analysed results. However, in many cases, the effectiveness of organisational learning from incident and accident reports vary (Ternov et al. 2004; Jacobsson et al. 2012). The events reported can also be uncommon and consequently the reporting and learning does not capture the entire functioning of safety processes or the true state of a changing organisation. As important as it is for organisations to have a reactive safety approach, it is equally important to have a proactive approach in which aspects in the organisation that can negatively affect work performance and safety are regularly identified and monitored. We propose the use of proactive safety management tools for organisations in order for them to adapt to their environment and to changing demands. With such tools, an organisation can collect and analyse human, organisational and technical information, and implement improvements when needed.

The application of such a tool for identification and monitoring can be seen as a way to bring about resilience in a system. Resilience engineering is a paradigm for safety management that focuses on how to help people and safety critical organisations cope with complexity. The definition of ‘resilience’ according to Hollnagel et al. (2006) is the ability of a system or an organisation to react to and recover from disturbances at an early stage, with minimal effect on the dynamic stability. Resilience is the ability to prevent something bad from happening and in doing so, foresight and coping are important. It means that an organisation must properly learn and remember the lessons of reported incidents and accidents. However, Hollnagel et al. encourage us to look for concurrences rather than causes, and instead of viewing concurrences as exceptions, we should view them as normal and, hence, also as inevitable.

A proactive approach to enhanced safety management called Tripod Delta was originally presented as a diagnostic evaluation tool for accident prevention on oil rigs. It is based on a checklist approach for carrying out safety ‘health checks’ (Hudson et al. 1994). The Tripod theory and methodology were developed at the Universities of Leiden and Manchester in co‐operation with the Dutch Royal/Shell Group in the 1980s and implementation began in the 1990s. The project resulted in a tool that has been applied in or been the basis of different research studies, for example (Sujan 2012). The tool is applied widely in the oil and gas industry.

According to Reason (1997), the underlying philosophy of Tripod Delta is to know what is controllable and what is not when it comes to the risks in an organisation. The strategy is to work with general failure types (GFTs), which are organisational factors that have been found through accident investigations to be latent conditions. Efficient safety management is dependent on efficient and ongoing identification of such GFTs and having efficient counter measures. The Tripod Delta tool is based on 11 GFTs that have been found to yield risks if not properly attended to. They represent organisational and workplace factors that contribute to unsafe acts and work injuries. Ten of the GFTs impact different work processes at a workplace and one GFT concerns the protective barriers or defences at the workplace. A short explanation of each of Reason's original GFTs used for safety management in oil drilling can be found in Table 1. Adverse events, injuries and accidents come from concurrence of such GFTs and unsafe acts. The unsafe acts (active failures and violations) are difficult to prevent (to err is human), but GFTs may be identified in advance and attended to proactively.

Table 1.

General failure types (GFTs) in the Tripod Delta tool used for safety management in oil drilling (Reason 1997)

| General failure type | Failures referring to |

|---|---|

| Hardware | Quality and availability of tools and equipment |

| Policies and responsibilities for purchasing | |

| Quality of stock system and supply | |

| Theft and loss of equipment | |

| Short‐term renting. Age of equipment | |

| Compliance to specifications | |

| Non‐standard use of equipment | |

| Design |

When it leads directly to the commission of errors and violations

|

| Maintenance management | The management rather than the execution of maintenance activities |

| Was the work planned safely? | |

| Did maintenance work or an associated stoppage cause a hazard? | |

| Was maintenance carried out in a timely fashion? | |

| Procedures | Quality, accuracy, relevance, availability and workability of procedures |

| Error enforcing conditions |

Conditions relating either to the workplace or the individual that can lead to unsafe acts

|

| Housekeeping | Problems have been present for a long time and various levels of the organisation have been aware of them but nothing has been done to correct them, such as inadequate investment, insufficient personnel, poor incentives, poor definition of responsibility, poor hardware |

| Incompatible goals |

Goal conflicts can occur at three levels:

|

| Communication |

Communication is not functioning. Information not transmitted or not received

|

| Organisation |

Deficiencies that blur responsibilities and allow warning signs to be overlooked

|

| Training |

|

| Defences | Failures in detection, warning, personnel protection, recovery, containment, escape and rescue |

Aim of the study

Sixty cases of MEs with parenteral cytotoxic drugs reported to the Swedish national authorities between 1996 and 2008 were examined for their characteristics (Fyhr & Akselsson 2012). The drugs involved, the type of errors, where in the medication process the errors took place, how the errors were discovered and the consequences for the patients were identified. However, it is also vital to go beyond identification and investigate why these errors occurred and the organisational weaknesses from which they originated. From this, we can learn and propose mitigation efforts to overcome these organisational weaknesses. The study presented in this paper performed such an investigation. To accomplish this, the authors developed a tool based on the Tripod Delta philosophy and the use of GFTs. By applying the GFT tool to the 60 previously reported MEs, the authors were able to identify GFTs underlying the errors and thus identify organisational weaknesses and latent conditions. This paper also proposes a proactive application of the tool by healthcare providers to enable proactive identification of organisational weaknesses.

The aims of this paper were to:

present the development of a proactive tool for identifying GFTs that fit the process of managing cytotoxic drugs in healthcare;

present the results from applying the tool to 60 reported MEs and thereby identify GFTs and active failures and

propose a proactive application of the tool by healthcare providers.

Materials and methods

Tool development

The GFT tool developed in the study to identify the origins of MEs of cytotoxic drugs was based on Reason's Tripod Delta tool (Table 1). Reason's original tool has been applied mainly in the oil and gas industry. Modifications had to be made to fit the process of managing cytotoxic drugs in healthcare. The modifications were performed by the first and second authors. The first author is a registered pharmacist and has worked as a supervisor of a pharmacy preparation service at a Swedish university hospital for nearly 20 years. The second author is a licensed physician with experience from the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare who works with investigations of serious medical events. During the tool development process, Reason's original GFTs were slightly modified by omitting some items not relevant for healthcare, such as quality of stock system, quality of supply, theft and loss of equipment, short‐term renting, age of equipment and compliance to specifications in the Hardware GFT; maintenance work or an associated stoppage causing a hazard in the Maintenance management GFT; management of contractor safety in the Organisation GFT; and personal protection, escape and rescue in the Defences GFT. Four major additions were made to the original GFTs to fit the healthcare setting (Table 2). These additions were based on the authors' expertise in the field. Software was added to the Hardware GFT heading, Follow‐up (Monitoring the patient) was added to the Maintenance management GFT heading, situational factors were included in the exemplifications of Error enforcing conditions GFT, and the absent or insufficient safety barriers item was included in Defences GFT. Exemplifications from healthcare of each GFT were added from a set of 30 cases reported to the Swedish national authorities on oral cytotoxic drugs.

Table 2.

General failure types (GFTs) tool adapted to healthcare with exemplifications. This table was used to analyse the medication errors in the study

| General failure type | Failure referring to | Exemplifications for healthcare |

|---|---|---|

| Hardware/Software |

Quality and availability of tools and equipment Quality and workability of software |

Usability of technical equipment, such as infusion pumps Diversity of technical and analytical equipment Condition of equipment Software, usability and compatibility with other systems Policies, responsibilities and specifications for purchase of equipment and software |

| Design |

When it leads directly to the commission of errors and violations Lack of external guidance on how to do something Lack of feedback when something is done Opaque with regard to the design object's inner working, or to the range of safe actions |

Poor working environment (e.g. lightning, temperature, humidity, limited working space, interruptions and disturbances) Bad design of documentation, such as medication lists Transcribing of information, such as prescriptions Similarity between different strengths of a drug Similarity between names and appearance of drugs |

| Maintenance managementv/Follow‐up (monitoring of patient) |

The management rather than the execution of maintenance activities. Follow‐up of treatment |

Maintenance of equipment. Room cleaning, equipment cleaning Patient monitoring during treatment Follow‐up of the treatment Did not react to the patient's adverse effects |

| Procedures | Quality, accuracy, relevance, availability and workability of procedures |

Lack of or incomplete procedures Updating of procedures Procedures not followed, violations (e.g. procedures for how to write prescriptions, for collaboration or for reporting to the next team) |

| Error enforcing conditions | Conditions relating either to the workplace or the individual that can lead to unsafe acts. Error‐producing or violation‐producing conditions | Situational factors: New Year's Eve, power failure, heavy workload due to some unexpected event |

| Housekeeping | Problems have been present for a long time and nothing has been done to correct them | Could be heavy workload, poor staffing and constant stress |

| Incompatible goals | Goal conflicts at three levels; (1) individual (preoccupation), (2) group (informal norms/safety goals), (3) organisational (safety/productivity goals) |

Clinical trial study protocol. Understaffing during vacations or unexpected illness |

| Communication | Communication is not functioning. Information not transmitted or not received |

Information poor or leading to misunderstanding. Information lost, information not given. Written information not clear or ambiguous. Handwritten prescription difficult to read. Telephone prescriptions |

| Organisation | Deficiencies that blur responsibilities and allow warning signals to be overlooked. Organisational structure and responsibilities |

Inappropriate planning of workflow Responsibilities unclear Trusted specialised colleague Reorganisation leads to lack of competence Poor safety culture (no incident reporting, no action taken on reports) |

| Training |

|

Examples: Just passed exam His/hers first job, in training. Not familiar with the drug, treatment or equipment. Lack of knowledge |

| Defences |

Failures in detection, warning, recovery, containment. Absent or insufficient safety barriers |

Double‐checking not working No double control Next professional in the process did not react Not checking patient's identity No proofreading of documents |

The preliminary GFT tool was then tested on 60 MEs reported to the Swedish national authorities between 1996 and 2008 involving a cytotoxic drug (Anatomic Therapeutic Chemical classification L01) and administered parenterally at a hospital. The investigational reports were obtained from the Swedish national authority, thus ensuring a fair richness in detail. For details of the 60 MEs, see Lund University Publications (2011).

For the 60 reports, the GFTs were identified according to the preliminary GFT tool containing exemplifications for healthcare. A maximum of four GFTs were allowed per case. The first and second author respectively, analysed the case descriptions in the 60 ME reports and identified GFTs. The two sets of results were then compared. For cases where judgements differed as to which GFTs should be applied, the tool was supplemented with explanatory notes relevant for healthcare. The 60 cases were judged again on two additional occasions for GFTs by the first two authors before the tool was judged to be sufficiently precise. The resulting tool containing the GFTs adapted to healthcare (and specifically for the managing of cytotoxic drugs) is presented in Table 2.

Final assessment of the ME reports

The tool presented in Table 2 was used in the final identification of GFTs in the 60 ME reports. As stated, these GFTs were considered to be latent conditions for the MEs to occur/develop.

In addition, for each ME case report, the active failures were identified and compiled in a table. The active failures according to Reason's (1995) classifications were divided into different categories of slips (mix‐up of drugs, pumps, patients, transcription error), mistakes (misinterpreted information, knowledge about treatment, follow‐up of patient, calculation error) or not possible to categorise. The responsible professional (doctor, pharmacist or nurse) and the consequences for the patients [death, harm or no harm according to NCC Merp (National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention)] were included in the table. The complete table will be sent upon request from the first author.

Results

The GFT tool

The GFT tool developed and applied to the 60 ME reports is presented in Table 2. Six case examples of the application are presented in Table 3. For each case, Table 3 includes a short description of what happened, contributing causes according to the authority's investigation, GFTs and active failures according to the Reason's (1995) classifications.

Table 3.

A selection of six cases with short descriptions of what happened, contributing causes, general failure types (GFTs) and active failures according to the Reason's (1995) classifications

| Where | What happened | Contributing causes | GFTs | Active failure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| County hospital | Lab result was missing resulting in four unnecessary treatments with cytostatics. A doctor missed the lab result, searched for it and found it after 5 months. No information on patient's condition | The patient met eight doctors during treatment period. There were global problems at the clinic (e.g. lack of consultants leading to high workload for doctors). Administrative routines were poor. There was no monitoring of test results |

Maintenance management/Follow‐up Procedures Housekeeping |

None Mixed responsibilities |

| Pharmacy at a university hospital | Preparation with epirubicin which also contained doxorubicin. Pharmacist discovered during next preparation. Patient received more than half of the dose before it was interrupted and corrected | A new bottle was fetched from the refrigerator. Drugs similar in colour and strength. Double‐checked and noticed a different batch number but did not react. Checking of the batch number has been introduced |

Design Defences |

Slips Pharmacist mixed the drugs |

| Pharmacy at a county hospital | Wrong drug prepared. Mix‐up during documentation before preparation. Prescription of vinblastine 10 mg IV injection became vincristine 2 mg. Nurse noticed that the prescription and what had been delivered did not conform; NOT given | An error when drug name was transferred to a computer program for preparation. Not discovered when double‐checked. Similarity in drug names. Very high workload, pressed working conditions |

Hardware/Software Design Incompatible goals Organisation |

Slips Pharmacist mixed up the documents |

| University hospital | Patient received another patient's drug. The patient discovered the mistake almost immediately and the infusion was stopped | Many treatments this Saturday. Both patients had had treatments before. The nurse did not check patients' IDs |

Incompatible goals Defences |

Slips Nurse mixed the patients |

| University hospital | Prescription of double dose of carboplatin and missed prescription of necessary infusion with fluid. Follow‐up with lab checks did not work. Child died after 6 days | Event analysis performed. Protocol for treatment not clear; dose discussed but still too high; to be given for 4–5 days. Routines for lab tests not followed. Weekend with unclear responsibilities among doctors. Nurses not familiar with treatment of children. Low staffing. Lack of open communication. Hierarchical culture |

Maintenance management/Follow‐up Organisation Defences |

Not possible to categorise |

| University hospital | Double dose prescribed in a clinical trial. Prescription was ‘Fluorouracil 1088 mg in NaCl 9 mg/mL in 1000 mL × 2 × 5 days'. Discovered during a review 7 months later. Patient had serious adverse reactions and needed intensive care | Protocol unclear ‘750 mg/m2 as a continuous IV infusion days 1–5 is given…’. According to rules at hospital, infusions should be changed every 12th hour. Doctor thought 750 mg/m2 was the dose to be given each time. Dose very high: nurses or pharmacists should have reacted |

Maintenance management/Follow‐up Communication Defences |

Mistake Doctor misinterpreted the protocol |

GFTs behind MEs

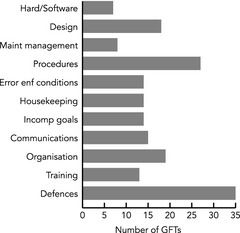

The frequency and distribution of the identified GFTs for the 60 ME cases studied are presented in Figure 1. The most frequently encountered GFTs were in Defences (35/60), Procedures (27/60), Organisation (19/60) and Design (18/60).

Figure 1.

Frequency and distribution of GFTs for the 60 MEs of parenteral cytotoxic drugs. GFT, general failure types; ME, medication error.

Examples in Defences are lack of or a failing to double check the patient's or drug′s identity or the dose of the drug. It could be doses that were too high and not discovered by any of the staff involved in treatment or preparation of the dose. Nearly all Procedures concern routines: routines that were lacking, were insufficient or were not followed. Examples of Organisation are defective co‐operation between different departments necessary for the care of the patient (such as the departments of paediatrics and oncology), inadequate definition of responsibility among doctors and badly planned reorganisations. The GFT Design category concerns look‐alike or sound‐alike drugs or ambulatory pumps, transfer of doses from prescription to requisition to pharmacy or to batch protocol, and poor work environment such as disturbances from telephones or visitors as well as a heavy workload.

Active failures behind MEs

The results concerning the active failures associated with the MEs are presented in Table 4. Among the active failures identified, 19 of the cases were classified as mistakes. Examples of mistakes were misinterpreted treatment, protocol or dose, calculation errors, monitoring of the patient and lack of knowledge. Thirty‐five of the cases were classified as slips. Examples of slips were mix‐up of drugs, doses, pumps, patients, documents and transcription errors. In six of the cases, no active failure or error could be determined. This could be because of an error in the protocol due to a miss in proofreading, a planned dose reduction that disappeared in the computer, mixed responsibilities among doctors or starting a treatment after an erroneous answer that the blood tests were fine. Of the mistakes, 13 were made by a doctor, 4 by a pharmacist and 2 by a nurse. Of the slips, 6 was made by a doctor, 21 by a pharmacist and 8 by a nurse. All of the cases where no active failure could be judged involved doctors.

Table 4.

The active failures categorised into ‘slips’, ‘mistakes’ or ‘not possible to categorise’. The responsible profession and the consequences for the patients are included

| Who | Type | What | Death | Harm | No harm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doctor | 13 mistakesa | 5 Misinterpreted | 3 | 10 | 1 |

| 4 Knowledge | |||||

| 2 Monitoring | |||||

| 2 Calculation | |||||

| 6 slips | 3 Mix‐up of protocols or drugs | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| 2 Transcription of prescription to pharmacy order | |||||

| 1 Data in wrong column | |||||

| 6 not possible to categorise | 2 | 1 | 3 | ||

| Nurse | 2 mistakes | 1 Misinterpreted | 2 | ||

| 1 Knowledge | |||||

| 8 slips | 7 Mix‐up of patients or drugs | 4 | 4 | ||

| 1 Transcription | |||||

| Pharmacist | 4 mistakes | 2 Misinterpreted | 1 | 3 | |

| 2 Calculation | |||||

| 21 slips | 20 Mix‐up of drugs, pumps, labels or documents | 4 | 17 | ||

| 1 Transcription error | |||||

| Total | 6 | 24 | 31 |

One mistake – two patients.

A proactive application of the tool by healthcare providers

When applying the GFT tool for the cytotoxic drug process (60 MEs), the authors were able to identify GFTs and various examples of them. Consequently, it can be confirmed that the tool makes a valuable contribution to the continuous improvement of the process of managing cytotoxic drugs in healthcare.

If an accident or incident happens the tool could be used when analysing the event. The tool facilitates the qualitative understanding of the influence of possible organisational weaknesses and local characteristics on risks. A group of professionals involved in the drug managing process are to take part when the tool is applied.

It is imperative that the organisation under investigation arranges sessions after each application to enable interpretation and discussion of the results, as well as to come up with valuable and user‐friendly solutions to the safety and work environment issues identified.

Discussion

Finding organisational weaknesses (i.e. factors that contribute to errors) in the process of managing cytotoxic drugs in healthcare means that we can move from a reactive to a proactive approach to managing errors. This would be the best for both the patients and the staff. This can be realised by properly learning the lessons from previous mishaps and working systematically to control and minimise latent conditions. To do so, good leadership is required to create a good safety climate, find useful tools, involve all the staff in the improvement processes and set the priorities. One such tool can be a self‐evaluation tool, such as the one developed in this study based on the Tripod Delta proactive approach. Sujan (2012) applied the thinking from Tripod Delta to managing risk profiles and to ‘basic problem factors’ when he developed a novel tool for organisational learning in a hospital dispensary. He used narratives, participation and feedback from the staff in developing the tool. The tool had a positive effect on safety‐related attitudes and behaviours of staff at the dispensary. For success, Sujan points to the importance of evidence about the efficacy of the approach in the form of visible improvements in the work environment.

Factors contributing to errors can be described in many ways. In this study, we use the GFT classification adjusted to healthcare and chemotherapy treatment. Over the years, the notion of latent conditions in healthcare has been described in different ways. Taylor‐Adams and Vincent (2004) used the term ‘contributory influencing factor’. ‘Latent risk factors’ has been used in anaesthesia by Van Beuzekom et al. (2010) and they included ‘teamwork’ and ‘team training’ along with ‘staffing’ and ‘situational awareness’ as new items. Some contributing factors are mentioned in these studies for GFTs such as design, communication, procedures/protocols and training/knowledge and skills.

In the current case, there is, of course, a great variety in what happened in the various instances of MEs, what professions were involved and why the MEs occurred. From this material, it can clearly be seen that the working condition in many of the cases was a common denominator behind the MEs. One example is the accumulation of MEs at a pharmacy in 2008. The management decided to transfer preparations, which resulted in a 35% increase in the number of preparations carried out. The transfer was ill‐planned, and within 1 month, five MEs were reported.

A frequent GFT was Design which included similarity between names and appearance of drugs and ambulatory pumps (look‐alike, sound‐alike) that led to mix‐ups. The problem with similar names is well‐known, leading the (Institute for Safe Medication Practice, 2013) to publish a list of similar drug names which are commonly confused. The pharmaceutical industry and the medical product agencies need to work for a sustainable solution to this problem. Transcribing information, such as prescriptions, is another well‐known risk (Patanwala et al. 2010; Ben‐Yehuda et al. 2011) and should, therefore be avoided.

Absent or insufficient safety barriers were included in the Defences GFT. For more than half of the cases stipulated, controls did not work. Double‐checking is defined as a procedure that requires two qualified health professionals, usually nurses, to independently check the medication before administrating it to the patient (Institute for Safe Medication Practice Canada, 2005). The evidence for double‐checking the administration of medicines was evaluated in a review study (Alsulami et al. 2012), where it was concluded that there is insufficient evidence to justify double‐checking of medicines. The results of the study presented in this paper may support a critical stance towards double‐checking. The findings also highlight the fact that information that could have prevented an accident was available, but nobody cared to check that the actions were correctly carried out according to this information. It is also noteworthy that no defences were thought of for almost half of the cases (i.e. defences that might have hindered the adverse event from taking place).

More than half of the MEs involved an active failure that was classified as a slip, a result similar to a study of prescribing errors in hospital inpatients by Dean et al. (2002). Interestingly, no active failure could be determined in 10% of the cases. This points to the fact that the model described by Reason is a simplification of reality, as it is with all models. When things go wrong, there are many reasons and often many actors involved.

We found the GFT tool to be useful for analysing a set of MEs in chemotherapy. Some of the GFTs are easy to understand and use, such as Training and Communication. Others, such as Incompatible goals and Error enforcing conditions, are understandable but difficult to use. This could be because we applied them to a set of reported MEs. To be able to understand the complexity behind a mishap, though, you need to be closer to the event and the staff involved.

Our data were limited to the content of the written reports from the national authorities. The reports vary in quality and amount of information provided due to different authors and changes over the years. In recent years of the investigation period, the healthcare facility or pharmacy carried out a root cause analysis before sending the report to the authorities, thus providing more comprehensive information.

For improved patient safety, we need to work proactively with the areas that cause the most or the worst errors. As a next step, we propose further development of the GFT tool and a proactive self‐evaluation tool, based on the Tripod Delta approach. First, many of the items connected to each of the different GFTs should be assembled in a questionnaire. In the Training category, the questions could include: Are new staff members introduced by means of a checklist? Is the training documented? Inspiration for the questions should come from everyday practice, incident reports and event analyses. For example, the staff should fill in the questionnaire every 6 months. All the ‘no’ answers should be highlighted so that the organisation can prioritise and discuss actions to be taken in suitable groups. This should be an iterative process mostly driven by the staff to gain their support and involvement in patient safety. This proactive tool can become a complement to existing incident reporting, event and risk analyses. It can help to improve an organisation's memory and to adapt to the dynamic changes that the organisation is a part of.

Fyhr A., Ternov S. & Ek Å. (2017) European Journal of Cancer Care 26, e12348, doi: 10.1111/ecc.12348 From a reactive to a proactive safety approach. Analysis of medication errors in chemotherapy using general failure types

References

- Alsulami Z., Conroy S. & Choonara I. (2012) Double checking the administration of medicines: what is the evidence? A systematic review. Archives of Disease in Childhood 97, 833–837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben‐Yehuda A., Bitton Y., Sharon P., Rotfeld E., Armon T. & Muszkat M. (2011) Risk factors for prescribing and transcribing medication errors among elderly patients during acute hospitalization: a cohort, case‐control study. Drugs and Aging 28, 491–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berdot S., Gillaizeau F., Caruba T., Prognon P., Durieux P. & Sabatier B. (2013) Drug administration errors in hospital inpatients: a systematic review. PLoS ONE 8, e68856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branowicki P., O'Neill J.B., Dwyer J.L., Marino B.L., Houlahan K. & Billett A. (2003) Improving complex medication systems: an interdisciplinary approach. Journal of Nursing Administration 33, 199–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vries E.N., Ramrattan M.A., Smorenburg S.M., Gouma D.J. & Boermeester M.A. (2008) The incidence and nature of in‐hospital adverse events: a systematic review. Quality and Safety in Health Care 17, 216–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean B., Schachter M., Vincent C. & Barber N. (2002) Causes of prescribing errors in hospital inpatients: a prospective study. Lancet 359, 1373–1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinning C., Branowicki P., O'Neill J. B., Marino B.L. & Billett A. (2005) Chemotherapy error reduction: a multidisciplinary approach to create templated order sets. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing 22, 20–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fyhr A. & Akselsson R. (2012) Characteristics of medication errors with parenteral cytotoxic drugs. European Journal of Cancer Care (England) 21, 606–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi T.K., Bartel S.B., Shulman L.N., Verrier D., Burdick E., Cleary A., Rothschild J.M., Leape L.L. & Bates D.W. (2005) Medication safety in the ambulatory chemotherapy setting. Cancer 104, 2477–2483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg A., Kramer S., Welch V., O'Sullivan E. & Hall S. (2006) Cancer Care Ontario's computerized physician order entry system: a province‐wide patient safety innovation. Healthcare Quarterly 9 Spec No, 108–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollnagel E., Woods D. & Leveson N. (2006) Resilience Engineering: Concepts and Precepts. Ashgate, Burlington, VT, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson P.T.W., Reason J.T., Wagenaar W.A., Bentley P.D., Primrose M. & Visser J.P. (1994) Tripod delta: proactive approach to enhanced safety. Journal of Petroleum Technology 46, 58–62. [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Safe Medication Practice (2013) ISMP's List of Confused Drug Names. Available at: http://www.ismp.org/tools/confuseddrugnames.pdf (accessed 20 January 2015).

- Institute for Safe Medication Practice Canada (2005) Lowering the risk of medication errors: independent safety checks. ISMP Canada Safety Bulletin 5, Issue 1, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsson A., Ek Å. & Akselsson R. (2012) Learning from incidents – a method for assessing the effectiveness of the learning cycle. Journal of Loss Prevention in the Process Industries 25, 561–570. [Google Scholar]

- Keers R.N., Williams S.D., Cooke J. & Ashcroft D.M. (2013) Causes of medication administration errors in hospitals: a systematic review of quantitative and qualitative evidence. Drug Safety 36, 1045–1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis P.J., Dornan T., Taylor D., Tully M.P., Wass V. & Ashcroft D.M. (2009) Prevalence, incidence and nature of prescribing errors in hospital inpatients: a systematic review. Drug Safety 32, 379–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund University Publications (2011) Compilation of lex Maria and HSAN Cases, Parenteral Cytotoxic Drugs, 1996‐2008. Available at: http://lup.lub.lu.se/luur/download?func&=downloadFile&recordOId&=1786272&fileOId&=1858430 (accessed 14 March 2014).

- Nerich V., Limat S., Demarchi M., Borg C., Rohrlich P.S., Deconinck E., Westeel V., Villanueva C., Woronoff‐Lemsi M.C. & Pivot X. (2010) Computerized physician order entry of injectable antineoplastic drugs: an epidemiologic study of prescribing medication errors. International Journal of Medical Informatics 79, 699–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patanwala A.E., Warholak T.L., Sanders A.B. & Erstad B.L. (2010) A prospective observational study of medication errors in a tertiary care emergency department. Annals of Emergency Medicine 55, 522–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reason J. (1995) Understanding adverse events: human factors. Quality in Health Care 4, 80–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reason J. (1997) Managing the Risks of Organizational Accidents. Ashgate, England. [Google Scholar]

- Schwappach D.L. & Wernli M. (2010) Medication errors in chemotherapy: incidence, types and involvement of patients in prevention. A review of the literature. European Journal of Cancer Care (England) 19, 285–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soop M., Fryksmark U., Koster M. & Haglund B. (2009) The incidence of adverse events in Swedish hospitals: a retrospective medical record review study. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 21, 285–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sujan M.A. (2012) A novel tool for organisational learning and its impact on safety culture in a hospital dispensary. Reliability Engineering and System Safety 101, 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor‐Adams S. & Vincent C. (2004) Systems analysis of clinical incidents. The London Protocol. Clinical Risk 10, 211–220. [Google Scholar]

- Ternov S., Tegenrot G. & Akselsson R. (2004) Operator‐centred local error management in air traffic control. Safety Science 42, 907–920. [Google Scholar]

- Tully M.P., Ashcroft D.M., Dornan T., Lewis P.J., Taylor D. & Wass V. (2009) The causes of and factors associated with prescribing errors in hospital inpatients: a systematic review. Drug Safety 32, 819–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Beuzekom M., Boer F., Akerboom S. & Hudson P. (2010) Patient safety: latent risk factors. British Journal of Anaesthesia 105, 52–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voeffray M., Pannatier A., Stupp R., Fucina N., Leyvraz S. & Wasserfallen J.‐B. (2006) Effect of computerisation on the quality and safety of chemotherapy prescription. Quality and Safety in Health Care 15, 418–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zernikow B., Michel E., Fleischhack G. & Bode U. (1999) Accidental iatrogenic intoxications by cytotoxic drugs: error analysis and practical preventive strategies. Drug Safety 21, 57–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]