Abstract

Background

The increasingly complex nature of care home residents’ health status means that this population requires significant multidisciplinary team input from health services. To address this, a multisector and multiprofessional enhanced healthcare programme was implemented in nursing homes across Gateshead Council in Northern England.

Study Aims

To explore the views and experiences of practitioners, social care officers, and carers involved in the enhanced health care in care home programme, in order to develop understanding of the service delivery model and associated workforce needs for the provision of health care to older residents.

Methods

A qualitative constructivist methodology was adopted. The study had two stages. Stage 1 explored the experiences of the programme enhanced healthcare workforce through group, dyad, and individual interviews with 45 participants. Stage 2 involved two workshops with 28 participants to develop Stage 1 findings (data were collected during February–March 2016). Thematic and content analysis were applied.

Findings

The enhanced healthcare programme provides a whole system approach to the delivery of proactive and responsive care for nursing home residents. The service model enables information exchange across organizational and professional boundaries that support effective decision making and problem solving.

Clinical Relevance

Understanding of the processes and outcomes of a model of integrated health care between public and independent sector care home services for older people.

Keywords: Enhanced health care, integrated working, nursing home

Since the early 1980s, the independent residential and nursing home sector (collectively known as care homes) in the United Kingdom (UK) has become a major provider of long‐term care for older people. Approximately 426,000 people live in these care facilities, of which 405,000 are 65 years of age and older. The number of care home residents has remained relatively stable since 2001, in spite of an 11% increase in the overall U.K. population of this age group (LaingBuisson, 2014). Gordon, Franklin, Bradshaw, Logan, and Elliott (2014) proposed that this is primarily because older people with chronic illnesses are now more likely to remain in their own homes longer, only relocating to a care home setting if and when their conditions become more complex or acute.

Residential and nursing homes in the UK are categorized by the types of care provided. Residents undergo needs assessments to determine which category of placement will offer the most appropriate care to match their needs. Nursing homes employ registered nurses to manage the care of residents with complex healthcare requirements and severe disabilities, and care assistants to deliver personal care support. The purpose of residential homes is the provision of personal care support, so only care assistant staff are employed. Any nursing care required in residential homes is provided by community nursing services. In both settings, medical care is provided by general practitioners (GPs), with referral to specialist services including community geriatrician and old age psychiatric specialists.

Studies investigating the health status of this population have found that admissions are driven by a combination of multiple morbidity, frailty, sensory impairment, and functional decline (Bowman, Whistler, & Ellerby, 2004; Gordon et al., 2014; Moore & Hanratty, 2013). For example, Gordon et al. (2014) found that the mean number of morbidities for care home residents is 5.5, and 75% of residents have some level of cognitive impairment. Gordon et al. (2014) concluded that “complex multi‐morbidity is a defining feature” of this population (p. 101).

Hence, residents require significant multidisciplinary team input to support the maximization of health and quality of life. Access to healthcare professionals is known to be problematic for this population in the UK. A number of inquiries indicate that the provision of allied health professional support is variable in accessibility (Care Quality Commission, 2011; Fletcher‐Smith, Drummond, Sackley, Moody, & Walker, 2014; Levin, Cardosa, Hoppitt, & Sackley, 2009). Levin et al.’s (2009) cross‐sectional postal survey of 121 care homes (with 95% response rate) indicated that most homes had access to a physiotherapist, chiropodist, optician, and hearing services. Yet less than half reported access to an occupational therapist, speech and language therapist, or dietician services. Funding and complex referral mechanisms were key factors that restricted access to services that are routinely available to people in other settings. Also, while most care homes are able to access specialist nurses reactively, few homes have access to proactive input from specialists to prevent problems arising in the first place (Kinley et al., 2014; Robbins, Gordon, Dyas, Logan, & Gladman, 2013).

In addition, reports have consistently highlighted that care home residents unable to attend GP practices struggle to access regular medical and medication reviews, as GP visits to care homes tend to provide a reactive service that involves limited care planning (British Geriatric Society [BGS], 2011). In response, the Royal College of General Practitioners and Royal College of Physicians (2016) has suggested that care homes should have dedicated GPs responsible for provision of medical services to their residents. Alldred et al. (2010), later supported by the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (2016), proposed that having these “link GPs” will also address polypharmacy‐related issues and unacceptable levels of medication errors.

The quality of care that residents receive in care homes affects the whole health economy. For example, Smith, Sherlaw‐Johnson, Ariti, and Barsley (2015) identified in their analysis of hospital admissions that care home residents 75 years of age and older have 40% to 50% more emergency admissions and accident and emergency attendances than the general population of the same age. Smith et al. suggested that without consistent, high‐quality medical care within the care home setting, the resident population will increasingly contribute to pressure across all health sectors. Acknowledging this, National Health Service (NHS) England (2014) promoted partnership working between the NHS, care home providers, and local authority social service departments with the aim of developing shared models of care providing holistic clinical reviews, medication reviews, and rehabilitation services for care home residents. This article reports on one such shared model of care.

Enhanced Health Care in Nursing Homes Programme

In the study location, the Gateshead care home programme (referred to as the enhanced healthcare programme) has been in operation for 5 years. It provides enhanced health care in care homes (with nursing beds) through multisector and multiprofessional working. This programme involves aligning both GP practices and older people nurse specialists (OPNS) to care homes with nursing beds. GPs are paid via an enhanced service and the OPNS are employed by the Community Services Provider. These services have direct access to a multidisciplinary community virtual ward and the wider health economy. The aim of this study was to explore the views and experiences of practitioners, social care officers, and carers who have been involved in the enhanced healthcare programme, in order to develop understanding of the service delivery model and workforce needs for the provision of health care to older residents living in nursing care homes.

Methods

To explore stakeholder views and experiences of the enhanced healthcare programme, a qualitative methodology was adopted within a constructivist paradigm. We felt explorations of shared meanings and understandings within professional and organizational contexts reflected the view “that all knowledge, and therefore all meaningful reality as such, is contingent upon human practices, being constructed in and out of interaction between human beings and their world, and developed and transmitted within an essentially social context” (Crotty, 1998, p. 42). The study design had two stages. Stage 1 was an exploration of the experiences of the workforce who have delivered services within the care home programme during the previous 5 years. Stage 2 involved workshops to disseminate preliminary findings from the Stage 1 interviews, and provide an opportunity for participants to contribute their views on the service model and workforce needs. Approval to undertake this study was granted by the Department of Healthcare, ethics committee, Northumbria University.

Settings and Participants

Stage 1

In Gateshead Council there are 16 care homes with nursing beds. All the nursing homes met the following criteria:

Care home with nursing beds

Involvement in the enhanced healthcare programme for at least 4 years

Referrals to specialist community services and patient safety concerns (2015 data)

It was not possible to hold interviews with staff in each home due to limitations in the project time scale. Therefore, to optimize sample diversity, a sampling matrix with the following criteria was utilized for the selection of 5 of the 16 care homes: small/large home; least/most referral to specialist community services; least/most safety concerns. This approach ensured that data were collected from a range of care environments and staff with varied experiences. Within each care home site, all care staff and management were invited to take part, and those available participated. NHS and local authority sector professionals with involvement in the enhanced healthcare programme were identified by service managers and were also invited to take part (see participant details in Table 1). Information explaining the study was made available via service managers to all interested parties, and written informed consent was collected at each interview.

Table 1.

Demographic and Role Details of Interview Participants

| Gender | Age (years) | Length in current role (years) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | 20–29 | 30–39 | 40–49 | 50–59 | 60–69 | Role | <1 | 1–5 | 6–10 | 11–20 | 20+ | |

| Care home staff (n= 11) | 1 | 10 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 2 × manager, 2 × deputy manager, 1 × clinical lead, 1 × staff nurse, 2 × senior carer, 3 × care assistant | 0 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| NHS staff (n = 27) | 4 | 23 | 0 | 6 | 11 | 10 | 0 | 18 × nurses, 4 × GPs, 2 × consultants, 1 × therapist, 2 × managers | 5 | 9 | 4 | 5 | 4 |

| Social services staff (n = 7) | 2 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 4 × assessing officer, 2 × social workers (adult), 1 × social worker (mental health) | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

Note. NHS = National Health Service; GP, general practitioner.

Stage 2

Invitations to take part in the workshops were distributed by the enhanced healthcare programme team and the Northumbria University research team. Both workshops were multiprofessional. Two events were held, with 11 and 17 practitioners, managers, and carers from older peoples’ services in the Gateshead (5 participants had also taken part in Stage 1).

Data Collection

Stage 1 data collection featured two strands: eight pair or group interviews and two individual interviews. The use of different forms of data collection ensured that individuals working in very small teams could participate while not detracting from resident care, and maintained a unidisciplinary approach to data collection. This facilitated greater openness and allowed for cocreated understandings to be explored during discussions. The interviews provided an opportunity for participants to give in‐depth descriptions of their experiences of the delivery of care within the enhanced healthcare programme. Across all types of interviews, participants were invited to explore their own experiences of delivering care within the enhanced healthcare programme; the knowledge, skills, and competencies required to deliver this care; their views on their workforce development needs; and the barriers they faced in everyday practice. Data and findings from Stage 1 were then discussed within two workshops during Stage 2 of data collection. At these events, participants were encouraged to record their views on Post‐it notes as discussions progressed. All data were collected between February and March 2016.

Data Analysis

Stage 1 audio‐recorded data were transcribed verbatim and open coded by individual members of the research team. This allowed elucidation and description of participants’ experiences of the Gateshead care home programme, whilst creating meaningful themes (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Randomly selected transcripts were independently coded by another team member, and the outcomes were compared with the original coding to validate findings. Following this, analyses from group interviews were then triangulated with dyad and individual interviews to explore how teams or individuals in different services worked together in the enhanced healthcare programme and how this affected care of residents and outcomes. Rigor was built into the data analysis process via discussing emerging preliminary findings with workshop participants. The individual views that were recorded on Post‐it notes and summary points made by the workshop facilitators were transcribed in preparation for analysis. Content analysis was used to systematically capture the themes and main ideas expressed during the Stage 2 workshop discussions (Mayring, 2000).

Findings

The participants were keen to share their experiences and views of working in, and with, care homes. The presentation of the findings commences with a discussion of the participants’ views that the resident population of contemporary nursing homes has extremely complex health problems that are challenging to even the most experienced practitioners. They highlighted the importance of “working together” across NHS and care home organizations to provide high‐quality and dignified care for older vulnerable, ill, and frail individuals. This is followed by an explication of the service delivery model of the enhanced healthcare programme. This programme is a whole system that enables practitioners to share information and knowledge, problem solve, and deliver care as a multidisciplinary team. The final section presents the participants’ views of workforce competencies required for responsive health care in care homes.

Older People With Complex Health and Personal Needs

Participants’ discussions of care home residents focused on the complexity and multifaceted nature of residents’ needs. Many suggested that the care home population is the most frail, complex and dependent of all our patients. Some participants proposed that caring for residents with such complex comorbidities poses a challenge for health and social care professionals and support workers, who are at times required to manage residents conflicting needs:

We're looking after people with so many multiple needs that you've got to weigh up all together all the time. That we can't treat people by the exact National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) standards for blood pressure and NICE standards for this, because they all conflict with each other and there's residents with 26 conditions, and you've got 92 problems and 43 medications. (NHS)

Participants proposed that care home residents have increasingly acute care needs, due to initiatives to support people to remain at home in order to avoid or delay admission to care homes and initiatives to reduce both hospital admissions and long hospital stays from care homes. While they acknowledged that achieving these objectives is desirable for older people, and for economic considerations, some felt that, consequently, care homes are providing more intense healthcare interventions:

We start and think about being able to deliver more hospital‐type things in that setting … to let residents stay in their own homes. (NHS)

And they're getting sent home from hospital… . They'll give them a quick course of IVs, antibiotics, and then they send them home within 2 days … but they've still got pneumonia. (care home participant [CH])

Participants suggested that the care home population includes an increasing number of “transient” residents, for example, residents admitted from their own home because they require respite care, functional assessment, or intermediate care, or residents transferred from hospital requiring intermediate care or rehabilitation services:

[They are] accessed as pressure placement beds, which is essentially a nursing bed in a private care home—step up. She didn't want to go back into hospital. This was local to her family, local to her GP surgery … we've got people transiently going in and out of nursing home areas … people that are so complex. (NHS)

Many participants felt that because of the increasingly complex and acute needs of older residents it should be acknowledged that this population requires specialist skills and expertise from multidisciplinary teams: “These are specialist care areas. Because you know, you need a lot of skills to do that” (NHS).

A Whole System Approach to Delivering Health Services in Care Homes Enhanced Healthcare Programme Service Delivery Model

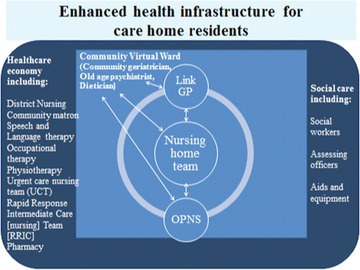

Participants’ discussions of their experiences of the enhanced healthcare programme informed the development of a diagrammatic representation of the service delivery model (Figure 1). Each care home's link GP completes weekly visits to review residents. Each care home also has a designated OPNS who visits two or three times per week, including participation in the weekly GP review. The regular meetings between the care home staff, GP, and OPNS were viewed as an effective vehicle for these professionals to “get to know each other,” to “know how everyone works,” and to “understand the other person's perspective and their working practices.” In situations where participants indicated that this way of working was effective, it was suggested that “everyone worked together to provide the best care for the older person.”

Figure 1.

Diagrammatic representation of Gateshead care home enhanced healthcare infrastructure developed through dialogue with the study participants. Note. GP = general practitioner; OPNS = older people nurse specialist.

The regular meetings provided opportunities for continuous review of a resident's physical and mental health status, and assessment of the effectiveness of the care plan:

Little things, like, if they're not taking their medication—you're not going to ring the GP up every time … “Oh, they're not taking their paracetamol. Will you change it?” You know, a GP is not going to come out just to do that. Because he's here, Tuesday, you are able to discuss and review the situation. (CH)

The GP and OPNS have direct access to specialist and consultant services. The most direct contact is through the “whole systems” virtual ward, which provides regular case management. There is a core membership of this community‐based virtual ward, including the community geriatrician, old age psychiatrist, and dietician. Other professionals are drawn into this group on a case‐by‐case basis. Here, complex and problematic situations are explored. Participants indicated that ongoing multidisciplinary problem solving was particularly important in those situations where conflict between treatment options of multiple chronic diseases was present:

If they've got all those things … I think if you've got all those people, all having that discussion on a regular basis, you know, sometimes you get an old age psychiatrist in, if you've got some problems, you know, around dementia and behaviors and chronic disease… . But just all being together and pulling together. You know, with the care home staff. And seeing exactly what's going on. It really makes a difference to management of care. (NHS)

Ability to access the wider economy of health care affects the support available to the older resident. At its best, it is this nestling of a care home within an infrastructure of specialist and responsive healthcare services that provides an effective network for enhanced health care to those living in nursing homes.

Responsive and timely resident‐centered care

The following case example occurred during one of the focus group interviews and is illustrative of how the service delivery model is responsive to an individual's personal situation:

This gentleman has been unwell for the past 6 weeks. He's had a urinary tract infection… . We've given him antibiotics in the care home for 3 weeks now. He has not responded to this treatment. I [GP] have just had a message from the OPNS to say that he's still unwell and his last urine specimen indicated that this is only sensitive to a particular antibiotic. In the past this situation may have led to an admission. But through discussion with the consultant geriatrician I can arrange for him to go and get a stat dose of the drug and then return to the home. So preventing an admission… . He also has dementia and depression. A stay in hospital, if it can be prevented, is better for his mental health. (NHS)

This is one of many examples that were discussed by the participants. It indicates that by using this service delivery model, early intervention and responsive care are delivered by a team working across sector and professional role boundaries.

Information transaction

Throughout the discussions there were many illustrations of professionals accessing and using different types of information to inform decisions about the management of residents’ care. The care home staff spoke of their knowledge of the residents’ biographies, preferences, aspirations, and behaviors. This knowledge of the person provided care staff with a baseline to identify when an individual's presentation had changed:

The staff here get to know the residents; they get to know any slight changes. It can be something just like somebody is mixing their tea in with their juice—this could indicate somebody having an infection. It can be minor or big changes. It just varies. (CH)

Often changes in behavior were described as the individual being “not quite right” or “not themselves.” Participants stressed the importance of sharing this information with nurses and other health professionals in order that an in‐depth assessment could be carried out, which would inform the management of care:

[Colleague] had seen him and was worried about his mood. I went in and said “no this is part of his apathy related to his dementia.” I didn't have to catch up because I knew him. All the information is staying together and now being used more holistically. (NHS)

In this example, the participant is suggesting that being able to readily access different types of knowledge is essential if person‐centered, holistic care is to be provided. Older residents frequently present with complex healthcare problems derived from their multiple chronic conditions, frailty, and functional problems. This requires professionals to make difficult choices between various treatment options. Such choices are not necessarily only based on “knowing how to treat a disease,” but may also involve weighing up individuals’ preferences, values, and aspirations for their lives. Hence, there is a complex interplay between knowledge of the person, knowledge of how the individual reacts to disease or presents with disease, and biomedical knowledge of how to treat disease. The participants suggested that the enhanced healthcare programme service delivery model enabled sharing of these different types of knowledge, and this enhanced the quality of decision making and problem solving.

Participants reported that during the regular meetings between care home staff, GPs, and OPNS, information is constantly shared and discussed: “She's [OPNS] got access to all the IT of the NHS … well, she looks at the notes. That helps us. And [OPNS] will access records and tell us loads about the resident” (CH).

However, participants, particularly those from care homes, described situations where continuity of care was adversely affected when information was not shared between professionals and across sectors:

A care home manager rang up and wanted to ask one of our wards about a resident who had been admitted. They knew her really well and had a wealth of information about her. The nurse was told “you're not a relative, we can't tell you anything.” (NHS)

This care home manager could not access up‐to‐date information about a resident who was due to be transferred back to the home following treatment for an acute illness. This lack of knowledge about in‐patient care and treatment could adversely affect the quality and continuity of care following discharge. Many other participants indicated that the quality of information that “traveled” with the individual following discharge from hospital was often very poor. In the preceding extract, information was not shared with the care home staff. However, when the OPNS contacted the ward, the ward staff readily provided up‐to‐date information about the resident. In this instance, the OPNS was able to support the care home staff to “navigate” through the healthcare service.

These discussions suggested that professionals utilize particular types of knowledge within their roles. For example, carers have more access to, and utilize, biographical knowledge in their daily interaction with residents and their families. In contrast, the GP may draw more on biomedical knowledge to inform decisions about treatment plans. Thus, the system is effective because all professionals know about different types of knowledge and how to access that knowledge. In this service delivery model, the OPNS fulfilled an important role in supporting information transaction across services, sectors, and agencies. Enhanced levels of information transaction had a consequent impact of ensuring that biographical knowledge informed care and treatment decisions and promoted continuity of care.

Workforce competency to provide responsive resident‐centered care

As presented in the previous section, participants generally reported positive experiences and outcomes of the whole systems service delivery model. However, they proposed that the sustainability of the model depended upon developing and maintaining workforce competency. During the Stage 2 workshops, participants discussed the multiple competencies required to provide preventative, enabling, and complex management of multimorbidity, frailty, and end‐of‐life care. Furthermore, the resident population can simultaneously require all of these levels of care. In addition, as individuals with particular health conditions enter the resident community, the workforce competency to deliver the required care may change. This would be problematic enough if the only element that changed was the care needs of the resident population. However, participants suggested that the workforce of the care home sector is also quite fluid due to staff attrition, staff sickness, and a reliance on agency staff. This results in variation in the skills and knowledge that care home staff have at any point in the rostered week: “There are nursing homes that have got staff trained up to use a syringe driver… . And then the bank nurse comes in to take over at the weekend and doesn't know how to use it” (NHS).

Whilst all staff may meet the requirement of holding professional or vocational qualifications, there is little standardization with respect to ongoing training, skills updates, and competency evaluation for individuals who work in the care home setting. This can be problematic:

There should be some standards in the home as well … in terms of bloods, some nurses can't take bloods … I have had three patients needing bloods in one visit. If it's an agency nurse who hasn't had their blood taking training ticked off they can't do it. (NHS)

This and many other competencies were discussed, and there was a consensus that there should be a direct relationship between role and competence, to reduce the risk of problems brought about by staffing concerns. It was also recognized that the range of health issues that could present in the care home setting was enormous, with some issues rarely occurring, and others presenting on a very regular basis. This observation stimulated participants to propose that it would not be unreasonable to “bring in” staff with specific competence for occasionally occurring issues. However, the care home workforce should possess the competence to provide care for regularly occurring issues:

We had one lady who was going into hospital every week. The OPNS got us trained where we can put a catheter into the bowel, and just drain that. And now the resident doesn't go into hospital, at all. I think that made a massive impact on her quality of life. (CH)

This participant highlighted the importance of the workforce continually developing new competencies to address residents’ unique needs. Although participants gave many examples of the various skills required to care for residents, they preferred to group skills into competency domains or categories. They proposed that there should be categories of “core,” “frequently required,” and “specific resident need” workforce competencies that align with resident populations’ needs.

Participants identified attitudinal core competencies they felt all staff should have, such as creating confidence and trust across the care team to know residents well, anticipate and meet their needs and wishes, promptly recognize minor deterioration, and ensure residents’ safety. This requires the team to value each other's knowledge, skills, and abilities to provide person or relationship‐centered dignified care. It also requires team members to support and empower each other to provide appropriate, responsive yet flexible care. A shared culture of working together across organizational boundaries, where the safety, health, and well‐being of the person is at the core is central to the enhanced healthcare approach.

Participants also identified core practice competencies for a preventative rather than reactive model of care, based upon care planning, early intervention, enablement, and rehabilitation. These competencies included a range of assessment skills, for example, comprehensive geriatric assessment, as undertaken by professional staff, and knowing residents’ individual preferences, norms, and behaviors, as undertaken by care support staff. Competencies in clinical decision making to meet complex care needs, managing multimorbidity (including polypharmacy), and identifying and managing frailty were also identified as critical. Appropriate referral to other agencies and shared record keeping were considered core competencies. Competence in monitoring and evaluating outcomes and amending care plans was prioritized. In addition, competence to lead and manage teams, particularly when working across organizational boundaries, was identified as a core requirement.

Frequently required competencies identified related to common issues such as managing exacerbation of chronic disease, changes in functional level, confusion and delirium, dual diagnosis, palliative, and end of life care. In contrast, competencies to meet specific client needs focused on skills required to respond effectively to individuals’ unique care needs.

Discussion

Effective, resident‐centered outcomes have been achieved by the enhanced health care in nursing homes programme in situations where there is a shared culture of working together across organizational and professional boundaries. This culture is fostered by professionals and organizations that are willing to come together as a team, and value each other's contribution to the provision of care for older people with complex needs. The recent Care Act (Legislation.gov.uk, 2014) underlines the drive towards person‐centeredness and efficiency by legislating for integrated services between health and social care providers. The enhanced healthcare programme is one approach to an integrated and shared model of care that brings the needs of the older person to the fore, whilst addressing the inequity in terms of restricted access to health care that has been experienced by older care home residents in the UK (BGS, 2011; Care Quality Commission, 2011).

The care home population presents with high levels of dependency, multimorbidity and frailty, and increasingly high levels of acute health problems (Faulkner & Parker, 2007; Gordon et al., 2014). Providing quality care for older residents is complex and requires a workforce that is flexible and responsive to changing resident needs (BGS, 2011). This workforce has to be capable of balancing personalized care that enables residents to enjoy life in a home setting, with the delivery of complex health care for ill and frail individuals. The whole systems approach of the enhanced health care in care homes programme actively enables practitioners to work across organizational boundaries. This was found to offer multiple benefits, including increased continuity of care and facilitation of regular review. Moreover, information exchange allowed greater sensitivity to and ability for practitioners to solve complex problems.

While the use of a whole systems approach may be a key benefit in the development of responsive resident‐centered care, the approach necessarily crosses organizational boundaries. Where there are boundaries, there is the potential for barriers. Indeed, the development of this service delivery model is hindered by several factors. These include difficulties in implementing standardized education and training; logistical issues underpinning the development, maintenance, and evaluation of the necessary workforce competencies; and the lack of standardized accessibility to information exchange processes.

For a whole systems approach to be successful in this setting, organizational issues must be considered. The contractual status of staff can be the determining factor in how and where continual professional development is accessed and how professional competencies are maintained. What patient information is available to staff across all aspects of the system has a direct impact on quality and continuity of care. Without systems in place to ensure that staff employed by private care homes can support residents in an integrated model of shared care with health and social care workers, such a model will be unsustainable.

Participants suggested that a whole systems integrated approach was needed in relation to how proficiency can be developed, achieved, maintained, and assessed. This includes:

The development of an appropriate competency framework aligned to the specific needs of the care home population

Agreement on standardized, appropriate, accessible ongoing personal development and assessment.

Development of the infrastructure to enable reliable assessment of competence and underpinning knowledge, at a range of levels from support worker to specialist and advanced practice.

McNall's (2012) whole systems workforce development model adopts a collaborative action research approach to generate workforce solutions that are suited to a specific context. The approach uses a coproduction method to develop competency frameworks and blended learning solutions. It also develops the infrastructure required to enable and support valid and reliable assessment of proficiency across the workforce. It includes a negotiated agreement of evaluation outcomes from all stakeholder perspectives.

In the context of the Gateshead enhanced healthcare programme, this evidence base and resulting workforce requirement could inform future outcomes‐based commissioning specifications. This would optimize the potential for developing a suitably competent workforce capable of delivering high‐quality care within the service delivery model that has developed.

Clinical Resources.

My Home Life: resources for promoting good practice in care homes: http://myhomelife.org.uk/good‐practice/8‐best‐practice‐themes/improving‐health‐and‐healthcare/

The UK national Vanguard programme: care homes: https://www.england.nhs.uk/ourwork/futurenhs/new‐care‐models/care‐homes‐sites/

Acknowledgments

We wish to express our appreciation to the participants who provided generous input into this study. We also wish to acknowledge the funding provided by Newcastle Gateshead Clinical Commissioning Group as part of their new models work programme, which enabled us to undertake this study.

References

- Alldred, D. P. , Lim, R. , Barber, N. , Raynor, D. K. , Buckle, P. , Savage, I. ,… Jesson, B. (2010). Care Home Use of Medicines Study (CHUMS): Medication errors in nursing & residential care homes—prevalence, consequences, causes and solutions. Report to the Patient Safety Research Portfolio, Department of Health. Retrieved from http://www.birmingham.ac.uk/Documents/college-mds/haps/projects/cfhep/psrp/finalreports/PS025CHUMS-FinalReportwithappendices.pdf Retrieved October 16, 2016

- Bowman, C. , Whistler, J. , & Ellerby, M. (2004). A national census of care home residents. Age and Ageing, 33(3), 561–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V. , & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- British Geriatric Society . (2011). A quest for quality in care homes. London, England: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Care Quality Commission . (2011). Supporting life after stroke: A review of services for people who have had a stroke and their carers. London, England: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Crotty, M. J. (1998). The foundations of social research: Meaning and perspective in the research process. London, England: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner, T. , & Parker, H . (2007). The organization, form and function of intermediate care services and systems in England: Results from a national survey. Health & Social Care in the Community 15(2), 146–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher‐Smith, J. , Drummond, A. , Sackley, C. , Moody, A. , & Walker, M. (2014). Occupational therapy for care home residents with stroke: What is routine national practice? British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 77(4), 265–273. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, A. L. , Franklin, M. , Bradshaw, L. , Logan, P. , & Elliott, R. (2014). Health status of UK care home residents: A cohort study. Age and Ageing, 43(1), 97–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinley, J. , Hockley, J. O. , Stone, L. , Dewey, M. , Hansford, P. , Stewart, R. ,… Sykes, N. (2014). The provision of care for residents dying in UK nursing care homes. Age and Ageing, 43(3), 375–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaingBuisson. (2014). Care of older people: UK market survey 2013/14. London, England: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Legislation.gov.uk. (2014). Care Act. Retrieved from http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2014/23/contents/enacted/data.htm

- Levin, S. , Cardosa, K. , Hoppitt, T. , & Sackley, C. (2009). The availability and use of allied health care in care homes in the Midlands, UK. International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation, 16(4), 218–224. [Google Scholar]

- Mayring, P. (2000). Qualitative content analysis. Forum. Qualitative Social Research, 1(2), 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- McNall, A. (2012). An emancipatory practice development study: Using critical discourse analysis to develop the theory and practice of sexual health workforce development Doctoral thesis, Northumbria University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK.

- Moore, D. , & Hanratty, B. (2013). “Out of sight, out of mind?” A review of data available on the health of care home residents in longitudinal and nationally representative cross‐sectional studies in the UK and Ireland. Age and Ageing, 42(6), 798–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Health Service England . (2014). Five year forward view Retrieved from https://www.google.co.uk/?gfe_rd=cr&ei=ZfNLV9-vF8Pm-gawtKWYBQ&gws_rd=ssl#q=nhs+england+2014+5+year+forward+view

- Robbins, I. , Gordon, A. , Dyas, J. , Logan, P. , & Gladman, J. (2013). Explaining the barriers to and tensions in delivering effective healthcare in UK care homes: A qualitative study. BMJ Open, 3. Retrieved from http://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/3/7/e003178.long [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royal College of General Practitioners and Royal College of Physicians. (2016). Patient care: A unified approach: A case study. London, England: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Royal Pharmaceutical Society. (2016). The right medicine: Improving care in care homes. London, England: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, P. , Sherlaw‐Johnson, C. , Ariti, C. , & Barsley, M. (2015). Quality watch. Focus on: Hospital admissions from care homes. London, England: Health Foundation and Nuffield Trust. [Google Scholar]