Abstract

Atrial fibrillation is the most prevalent cardiac arrhythmia, affecting 10% of those aged over 80 years. Despite multiple treatment options, it remains an independent prognostic marker of mortality due to its association with clinical sequelae, particularly cerebrovascular events. Management can be broadly divided into treatment of the arrhythmia, via rhythm or rate control, and stroke thromboprophylaxis via anticoagulation. Traditional options for pharmacotherapy include negatively chronotropic drugs such as β-blockers, and/or arrhythmia-modifying drugs such as amiodarone. More recently, catheter ablation has emerged as a suitable alternative for selected patients. Additionally, there has been extensive research to assess the role of novel oral anticoagulants as alternatives to warfarin therapy. There is mounting evidence to suggest that they provide comparable efficacy, while being associated with lower bleeding complications. While these findings are promising, recent controversies have arisen with the use of novel oral anticoagulants. Further research is warranted to fully elucidate mechanisms and establish antidotes so that treatment options can be appropriately directed.

Keywords: Atrial fibrillation, warfarin, novel anticoagulants, catheter ablation, arrhythmia-modifying drugs

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation is the commonest cardiac arrhythmia, affecting 1–2% of the general population in the developed world and 10% of those aged over 80 years.1 It is an important precipitant of cerebrovascular events and has adverse effects on quality of life. This review provides an overview of the management strategies involved in atrial fibrillation, including pharmacological agents, catheter ablation and left atrial appendage occlusion devices. Full exploration of recent evidence underpinning use of the novel oral anticoagulants and its comparison with conventional warfarin therapy is also provided.

Methods

The authors performed electronic searches of The Cochrane Library 2015, MEDLINE (1996–2015) and EMBASE (1996–2015) with use of specific terms. For pragmatic purposes, searches were limited to those indexed from 1996 onwards. Only studies of English language were included. Grey-literature sources such as NHS evidence were also utilised to obtain material of interest, albeit restricted to specific domains. Other relevant sources included ESC 2010 guidelines and local/regional presentations (Leeds General Infirmary, UK).

Atrial fibrillation categorisation

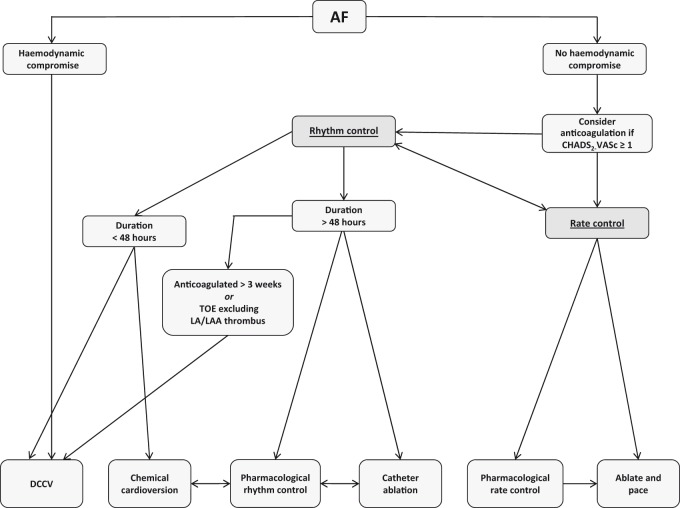

A number of categorisation systems have been utilised to guide management strategy, with the classical method relying upon the anatomical distinction between ‘valvular’ and ‘non-valvular’ atrial fibrillation. This has now been superseded by a categorisation based upon the existence of haemodynamic compromise, indicated by shock (blood pressure < 90/60 mmHg), chest pain, pulmonary oedema or syncope. This classification is useful in emergency settings as it highlights patients in need of rapid cardioversion. The most commonly used classification is based on temporal characteristics and comprises five subgroups: first diagnosed atrial fibrillation, representing the initial presentation; paroxysmal atrial fibrillation which is a self-terminating episode lasting less than seven days; persistent atrial fibrillation which is an episode lasting between seven days and one year; long-standing persistent atrial fibrillation where the arrhythmia lasts over a year but where there remains potential for rhythm control; and permanent atrial fibrillation, where the arrhythmia is accepted and no attempts are made to restore normal sinus rhythm. Irrespective of the method of categorisation used, underlying principles in management are treatment of the arrhythmia by rate or rhythm control, and reduction in systemic thromboembolic risk using anticoagulation. Figure 1 provides a summary of the management algorithm.2

Figure 1.

Management algorithm for atrial fibrillation (adapted from 2010 ESC guidelines). For patients with haemodynamic compromise secondary to atrial fibrillation, acute direct current cardioversion is the treatment of choice. For those without haemodynamic compromise, once appropriate anticoagulation has been initiated, a choice can be made between rate and rhythm control. In both cases, pharmacotherapy plays an important role. The drugs typically used for rate control are β-blockers, non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers and digoxin. Acute chemical cardioversion is usually achieved with intravenous amiodarone or flecainide, although novel alternatives such as vernakalant and ibutilide are now available. Amiodarone, flecainide and sotalol are the drugs of choice for longer-term pharmacological rhythm control.

Rhythm and rate control

For patients in acute atrial fibrillation associated with haemodynamic compromise, synchronised external direct current cardioversion is the treatment of choice. It is imperative, however, that associated conditions such as infection are identified with urgency as treatment of the underlying disorder rather than the dysrhythmia per se often leads to rapid resolution of symptoms and physiological parameters. In those instances where atrial fibrillation is not associated with haemodynamic compromise, rhythm or rate control may be appropriate depending on the specific clinical scenario.

Rhythm control

It is reasonable to consider rhythm control as an initial approach in young patients (<65 years) who are symptomatic and would be suitable for escalating treatments such as ablation if indicated.2 In those instances where atrial fibrillation is secondary to a treatable precipitant, such as infection or hyperthyroidism, a rhythm control strategy would also be pertinent. Furthermore, in patients with impaired left ventricular function, rhythm control is preferable since restoration of normal sinus rhythm can improve cardiac output. For those with a first diagnosis of atrial fibrillation with symptoms, acute cardioversion (via either pharmacological or electrical means) is appropriate if the duration does not exceed 48 h. Otherwise, exclusion of intra-cardiac thrombus by transoesophageal echocardiography (TOE) is required. Generally, the initial management strategy comprises anticoagulation with rate control, followed by cardioversion if patients remain symptomatic. Suitability depends on factors including age, co-morbidities and intrusiveness of symptoms. In persistently refractory cases, referral for consideration of atrial fibrillation ablation (especially in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation) may be appropriate.

(a) Arrhythmia-modifying drugs

The use of arrhythmia-modifying drugs (AMDs) has been a mainstay in the treatment of acute atrial fibrillation and for long-term control. Amiodarone is most widely used, and clinical trials have consistently shown it to be the most efficacious in maintaining normal sinus rhythm. Nonetheless, long-term success rates remain disappointing with a recurrence rate of at least 35% across multiple trials.3 Alternatives for rhythm control include flecainide, sotalol and novel agents such as vernakalant and ibutulide.2 Vernakalant has been specifically approved in ESC guidelines as an effective alternative for acute chemical cardioversion (≤7 days for non-surgical patients and ≤3 days for surgical patients). It has atria-selective properties, which avoids the pro-arrhythmic risk associated with QT prolongation of action potentials in the ventricles. An overview of anti-arrhythmic drugs is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of mechanisms, potency, side effects and contraindications of anti-arrhythmic drugs.

| Class | Predominant mechanism of action | Time to peak action | Dose and mode of administration | Side effects | Contraindications (absolute and relative) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amiodarone | III | Potassium channel blockade resulting in Phase 3 AP prolongation (reduced efflux) | Hours to weeks | 1200–1600 mg IV (loading), 200 mg PO TDS for 1/52 with weaning regimen to 200 mg PO OD (maintenance) | Hypotension, thrombophlebitis, thyroid dysfunction, pulmonary fibrosis, INR prolongation, photosensitivity, QT prolongation | Thyroid disease, chronic liver or lung disease, pregnancy |

| Flecainide | Ic | Sodium channel blockade resulting in Phase 0 AP prolongation (reduced influx) | 3–4 h | 2 mg/kg IV (loading), 50 mg PO BD initially (maintenance) | Pro-arrhythmias, acute pulmonary oedema (negatively inotropic), CNS effects, QT prolongation, risk of conversion into atrial flutter with 1:1 conduction | Impaired ventricular function, significant coronary artery disease, pregnancy |

| Sotalol | III | Potassium channel blockade resulting in Phase 3 AP prolongation (reduced efflux), suppresses spontaneous depolarisation during Phase 4, non-selective (β1 and 2) adrenoceptor antagonist | 2–3 h | 75 mg IV BD or 80 mg PO BD initially | QT prolongation, hypotension, fatigue | Impaired ventricular function, peripheral vascular disease, asthma, pregnancy |

| Vernakalant | III | Atrial-selective potassium and sodium channel blockade resulting in AP prolongation | 1–2 h | 3 mg/kg IV | Bradycardia, hypotension, CNS effects | Severe AS, systolic BP < 100 mmHg, NYHA class III/IV heart failure, recent ACS (within 30 days) |

| Ibutilide | III | Activation of sodium channel (influx) resulting in Phase 0 AP prolongation | 30 min | 1 mg IV | Pro-arrhythmias, headache | Recent ACS (within 30 day), sick sinus syndrome |

AP: action potential, IV: intravenous, PO: oral, OD: once daily, BD: twice daily, TDS: three times daily, INR: international normalised ratio, CNS: central nervous system, AS: aortic stenosis, BP: blood pressure, NYHA: New York Heart Association, ACS: acute coronary syndrome.

(b) Electrical cardioversion

For patients with haemodynamic compromise precipitated by atrial fibrillation, external direct current cardioversion is used as an emergency measure to rapidly restore normal sinus rhythm. It can also be utilised as an elective procedure in patients who are clinically stable. Patients require three weeks of therapeutic anticoagulation prior to the procedure and success rates are improved by concurrent therapy with anti-arrhythmic drugs. Factors which are inversely related to success include arrhythmia duration and left atrial dimensions. Overall, success rates are around 70–80% immediately post procedure, albeit with a 50% risk of recurrence within one year. In such refractory cases, internal direct current cardioversion with electrode catheters is a reasonable option to consider.

(c) Pulmonary vein ablation

In patients with persistent symptoms despite anti-arrhythmic drug therapy (and/or a rate-limiting agent), referral to an electrophysiologist for consideration of ablation is appropriate. The technique involves use of radiofrequency or cryothermal energy to destroy cells that form the foci for impulse initiation and propagation. The discovery that ectopy frequently arises at junctions between the pulmonary veins and left atrium provided the rationale for pulmonary vein isolation as a method to electrically isolate this trigger zone from surrounding tissue.4 Subsequent research has explored whether additional substrate modifications, for example via left atrial linear ablation, provides adjunct benefit. However, the results of the STAR-AF2 study has demonstrated that additional procedures beyond pulmonary vein isolation do not appear to confer improvement in symptoms and thus, a ‘less is more’ strategy may be preferable.5

In paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, most studies have shown success rates of >80%, whereas 50–60% is more typical for persistent atrial fibrillation.6 Potential improvement in quality of life following intervention needs to be balanced against the 3–4% risk of complications, which include stroke, cardiac tamponade and atrioventricular nodal block. Outcome data suggest that normal sinus rhythm is better maintained after ablation in comparison with conventional anti-arrhythmic drug therapy. However, results appear to be heavily influenced by inclusion criteria and pre-selected endpoints. Most significantly, there have been no prospective studies to indicate that ablation improves mortality, though a recent analysis of registry data has offered encouraging findings.7 Thus, at present, guidelines indicate that intrusive symptoms are a mandatory prerequisite for pulmonary vein ablation.

Rate control

(a) Pharmacotherapy

Controlling the ventricular rate is an effective management strategy in atrial fibrillation, particularly in elderly patients with minimal or absent symptoms. Pharmacotherapy generally falls into three categories: β-blockers, non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers and digoxin. β-blockers are first-line therapy and usually effective. Bisoprolol is the most commonly used agent, but alternatives with shorter half-lives such as metoprolol or atenolol are options if tolerability is a concern, for instance, in patients with a history of emphysema. Situations in which β-blockers are contraindicated include hypotension, acute pulmonary oedema or brittle asthma. Non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers are a useful alternative for the latter group, but should also be avoided in the setting of hypotension or acute pulmonary oedema, as well as chronic, significant ventricular dysfunction. Lastly, digoxin provides a positive inotropic effect and enables use irrespective of haemodynamic status, which is particularly beneficial in critical illness. However, since it is not effective at suppressing exercise-induced tachycardia, use is limited to sedentary patients or as adjunct therapy. In terms of target heart rate, prior guidelines advocated strict control to improve symptoms and quality of life. However, the RACE2 trial has demonstrated that lenient control (resting heart rate < 110 bpm) is as effective as strict control (resting heart rate < 80 bpm or heart rate during moderate exercise < 110 bpm) while being easier to achieve.8

(b) Atrioventricular node ablation

For patients in paroxysmal atrial fibrillation that is symptomatically intrusive and drug-refractory, permanent pacemaker implantation (conventionally DDDR/MS) followed by atrioventricular node ablation can be effective in suppressing symptoms and improving quality of life.9 Nonetheless, in comparison with ablation procedures, it should be considered palliative as it acts indirectly by regulating ventricular rate and does not directly eliminate electrophysiological substrate. Additionally, there are inherent associated risks with any invasive procedure, and thus, an individualistic approach with a pragmatic stance must be adopted. The indications for ablation in the context of persistent atrial fibrillation are less convincing.

A second, potential indication for atrioventricular node ablation is in the context of congestive cardiac failure. The role of cardiac synchronisation therapy in patients with refractory cardiac failure, evidence of inter-ventricular dyssynchrony and normal sinus rhythm is well established. In the context of atrial fibrillation, however, its benefits are not as defined and subsequently, recent studies have assessed the specific role of atrioventricular node ablation in these cohorts to aid synchronised and complete biventricular capture. Results from a systematic review appear to advocate atrioventricular node ablation, with demonstrable improvements in functional class and mortality benefits.10

Rate versus rhythm control

Historically, the prevailing opinion had been that rhythm control is superior to rate control. The PIAF trial was the first to suggest that pharmacological rate control was comparable to rhythm control achieved by anti-arrhythmic drugs and/or electrical cardioversion.11 This was followed by the RACE and AFFIRM studies, which demonstrated that both strategies were equivalent with regard to morbidity and mortality.12,13 Based on these findings, the previously held notion regarding superiority of rhythm control was weakened. One aspect that was not accounted for in the initial trials was the influence of the adverse effects associated with anti-arrhythmic drugs on the overall outcomes. With this in mind, data from the AFFIRM study was re-analysed using an on-treatment analysis method. Interestingly, this demonstrated that normal sinus rhythm was associated with a 47% increase in survival compared to atrial fibrillation, while use of anti-arrhythmic drugs conferred a 49% increase in mortality.14 The conclusion drawn from this analysis was that achieving normal sinus rhythm for patients in atrial fibrillation is indeed advantageous. However, the adverse effects of the anti-arrhythmic drugs mitigate any potential benefit.

Scoring systems for risk stratification

Various analyses have identified clinical factors that increase the risk of thromboembolism in the context of atrial fibrillation. One such study, entitled SPAF,15 resulted in the formation of the CHADS2 scoring system, which became the first stroke risk predictor for patients in atrial fibrillation. However, while it has clear use in identifying those at highest risk (≥2), it was less robust at highlighting those with ‘low risk’. The more recently developed CHA2DS2-VASc criteria (Table 2) is superior at identifying true ‘low risk’ patients and has now superseded CHADS2. However, the decision to anticoagulate needs to be balanced against associated risks of haemorrhage. To quantify bleeding risk, the HAS-BLED score (Table 2) has been advocated in ESC guidelines due to its predictive value and its ability to identify risk factors which can be actively managed.8 All patients being considered for anticoagulation require a formal assessment of bleeding risk. A high HAS-BLED score (≥3) does not necessarily preclude anticoagulation, but accentuates the need for close monitoring and identification of reversible risk factors.

Table 2.

CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED scoring systems.

| Risk factor | CHA2DS2-VASc score |

| Chronic heart failure | 1 |

| Hypertension | 1 |

| Age ≥ 75 years | 2 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1 |

| Previous cerebrovascular event | 2 |

| Vascular disease | 1 |

| Female gender | 1 |

| Age 65–74 years | 1 |

| Risk factor | HAS-BLED score |

| Hypertension | 1 |

| Renal impairment | 1 |

| Impaired liver function | 1 |

| Previous cerebrovascular accident | 1 |

| History of bleeding | 1 |

| Labile international normalised ratios | 1 |

| Age > 65 | 1 |

| Antiplatelet or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug therapy | 1 |

| Alcohol consumption | 1 |

Warfarin versus novel oral anticoagulants

With respect to stroke thromboprophylaxis in atrial fibrillation, initial trials compared aspirin to warfarin and these two agents were the mainstay of treatment for decades. However, it is now apparent that the benefits of aspirin in stroke prevention are weak, while the rates of intracranial haemorrhage are comparable to warfarin. As such, use of aspirin is no longer recommended for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation and current guidelines instead recommend that all patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score ≥ 1 should be strongly considered for anticoagulation.2

While warfarin remains an effective agent in stroke thromboprophylaxis, reducing risk by up to two-thirds, it has well-established drawbacks. Due to its narrow therapeutic index, patients require close monitoring of their international normalised ratio, which necessitates frequent blood testing. It also has the potential for interaction with a wide range of pharmacological agents. In recent years, a number of alternative agents have been developed, collectively termed the novel oral anticoagulants. In contrast to warfarin, these drugs have a predictable pharmacokinetic profile, fewer drug interactions and do not require monitoring.16 The four novel oral anticoagulants currently in use are the direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran, and the factor Xa inhibitors rivaroxaban, apixaban and edoxaban. For a summary of their profiles, see Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison between warfarin and novel oral anticoagulants.

| Warfarin | Dabigatran | Rivaroxaban | Apixaban | Edoxaban | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanism | Inhibition of Vitamin K-dependent clotting factors (II, VII, IX, X) | Inhibition of factor II (thrombin) | Inhibition of factor Xa | Inhibition of factor Xa | Inhibition of factor Xa |

| Administration | OD | BD | OD | BD | OD |

| Dose | Variable | 150 mg BD (or 110 mg BD) | 20 mg OD (or 15 mg OD) | 5 mg BD (or 2.5 mg BD) | 60 mg OD (or 30 mg OD) |

| Time to peak effect | 3–5 days | 3 h | 3 h | 3 h | 1–2 h |

| Bioavailability | 100% | 6% | 70% | 50% | 62% |

| Renal clearance | 0% | 80% | 35% | 25% | 40% |

| Monitoring | Required | Not required | Not required | Not required | Not required |

| Antidote | Vitamin K | None currently | None currently | None currently | None currently |

| Special considerations | Absorption pH dependent and reduced in patients taking PPI, reduced dose if age > 80 years, CI if eGFR <30 mL/min | Requirement for high oral intake, reduced dose if eGFR < 50 mL/min (CI if eGFR <15 m:/min) | Reduced dose if creatinine clearance 15–29 mL/min (CI if < 15 mL/min), or if ≥ 2 of: age ≥ 80 years, weight ≤ 60 kg, creatinine ≥133 µmol/L | Reduced dose if clearance 15–50 mL/min (CI if < 15 mL/min) |

OD: once daily, BD: twice daily, PPI: proton pump inhibitor, CI: contraindication, eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration.

Dabigatran was the first novel oral anticoagulant to demonstrate effective thromboprophylaxis in atrial fibrillation, based on the RELY trial.17 The lower dose (110 mg twice daily) was non-inferior to warfarin with respect to stroke and systemic embolism, while being associated with lower rates of major haemorrhage. The higher dose (150 mg twice daily) was associated with lower rates of stroke and systemic embolism, at the expense of a higher bleeding rate. No differences in all-cause mortality were noted. Subsequently, the ROCKET-AF trial compared use of rivaroxaban to warfarin in atrial fibrillation18 and found it to be non-inferior with respect to stroke and systemic embolism, with comparable rates of mortality. However, a retrospective analysis found increased rates of gastrointestinal haemorrhage.19 The ARISTOTLE trial followed on from ROCKET-AF and demonstrated that use of apixaban was associated with significant reductions in systemic embolism, as well as major bleeding.20 Of significance, this was the first trial to demonstrate a mortality benefit compared to warfarin. Edoxaban is the newest addition to the novel oral anticoagulants collective, and the ENGAGE-AF-TIMI trial demonstrated it to be non-inferior to warfarin in terms of systemic embolism.21 The incidence of major bleeds was significantly reduced, with the exception of gastrointestinal haemorrhage when high-dose edoxaban was administered.

The distinction between ‘valvular’ and ‘non-valvular’ atrial fibrillation becomes important when selecting anticoagulant agent. Classically, the former is restricted to instances where atrial fibrillation occurs in the presence of rheumatic mitral valve disease, prosthetic mitral valve or mitral valve repair. However, there is variability in pathogenesis between these individual entities and in view of this, recent proposals have advocated a more precise definition (‘MARM-AF’ – mechanical and rheumatic mitral valvular atrial fibrillation).22 While this classification has been largely superseded by temporal categorisation, the increased popularity of novel oral anticoagulants has brought anatomical classification back into prominence since they are currently only licensed for use in non-valvular atrial fibrillation.

Controversies surrounding NOACs

Usage of novel oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation has increased in recent years, yet controversies still exist among this burgeoning group of drugs. Until the recent release of edoxaban, rivaroxaban was unique among the novel oral anticoagulants in being a once daily regimen. This was perceived to provide an advantage with regard to patient compliance. However, as with all novel oral anticoagulants, its relatively short half-life poses unresolved questions about pharmacokinetic efficacy. Interestingly, a twice daily regimen for rivaroxaban is advocated in the context of acute coronary syndromes. There is also real-world data to indicate that reduced dosing regimens are suitable in certain clinical contexts. For instance, a retrospective study in East Asian patients has demonstrated improved safety and efficacy compared to warfarin when lower doses (10–15 mg once daily) were administered, perhaps correlated with reduced body mass.23

An ongoing controversy with rivaroxaban relates to the discovery that a faulty, point-of-care device for international normalised ratio testing was utilised during the ROCKET-AF study.24 This was subsequently recalled in 2014 due to its tendency to under estimate international normalised ratio. Consequently, a significant proportion of those in the warfarin arm deemed to be within therapeutic range may have been over-anticoagulated. This has clear confounding potential on the relative bleeding rates observed between warfarin and rivaroxaban. As a result, the validity of the trial findings have been called into question, and indeed, some are advocating a further trial to provide clarity.25

One of the purported benefits of novel oral anticoagulants compared to warfarin is the predictability of their effects. However, it is not uncommon for patients administered warfarin to be out of therapeutic range, indicating sub-optimal anticoagulation. In contrast, the fixed dosing regimen of novel oral anticoagulants theoretically provides a more consistent pharmacological effect. However, this notion is predicated upon adequate compliance which may not manifest in large clinical trials where patients are well-motivated and closely monitored. The twice-daily dosing regimens of apixaban and dabigatran, in contrast to once-daily warfarin, may impact upon compliance since real-world registry data suggest that patients treated with once-daily regimens generally display greater adherence.26

The issue of cost–benefit comparisons between warfarin and novel oral anticoagulants warrants further scrutiny. While the aforementioned trial data cast novel oral anticoagulants favourably, particularly apixaban, improved clinical outcomes were manifest as relative risk reductions, with absolute benefits rather more modest. For instance, the ARISTOTLE trial demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in stroke with apixaban, however, the number needed to treat to achieve this benefit over the 1.8-year follow-up period was 175. Given that a month’s supply of apixaban is threefold more expensive than equivalent costs of warfarin pharmacotherapy and monitoring, it is questionable whether the extra expenditure is justifiable.27

Lastly, warfarin has a potent antidote to reverse bleeding in the form of vitamin K, which replenishes stores of clotting factors II, VII, IX and X. In contrast, there are currently no specific antidotes for novel oral anticoagulants licensed for use, and management involves prompt drug discontinuation with close monitoring. However, there are agents currently in development. One such example is the monoclonal antibody idarucizumab, which has acquired approval for the reversal of dabigatran in patients requiring urgent surgical procedures.28

Overall, there is no question that novel oral anticoagulants provide an attractive and efficacious alternative to warfarin in the management of atrial fibrillation. However, warfarin remains useful and well-established. For those patients who are consistently within therapeutic range and have no concerns regarding tolerability, the benefits of switching to a novel oral anticoagulant may be equivocal. As such, the binary distinction between use of warfarin or novel oral anticoagulant for all patients in atrial fibrillation may be too simplistic. A more nuanced approach whereby novel oral anticoagulants are reserved for patients at highest risk of bleeding events on warfarin, such as those frequently outside of therapeutic range, is perhaps more appropriate.

Left atrial appendage closure devices

The left atrial appendage is the main source of intra-cardiac thrombus in non-valvular atrial fibrillation, and thus, occlusion of this anatomical region via closure devices was deemed an attractive alternative in selected patients. Specifically, it is relevant in those who fulfil the criteria for long-term anticoagulation (warfarin or novel oral anticoagulant), but where a clear intolerance exists or a high risk of bleeding. The PROTECT-AF and PREVAIL trials, which compared the Watchman device to warfarin therapy, found left atrial appendage occlusion to be non-inferior to warfarin in stroke prevention, while possibly lowering bleeding risk.29,30 While these results are encouraging, a few caveats need to be borne in mind. Use of left atrial appendage closure devices introduces a procedural risk that is avoidable with pharmacotherapy. Additionally, antiplatelet therapy is required subsequent to device deployment which prolongs bleeding risk, while the minimum duration of antiplatelet therapy remains unknown. Overall, the evidence base remains limited and further trials are necessary before it can be incorporated within routine practice.

Conclusions

Significant progress has been made in our understanding of the pathophysiology of atrial fibrillation in the past two decades, and advances in treatment options such as targeted catheter ablation reflect this. Furthermore the introduction of novel oral anticoagulant therapy for stroke thromboprophylaxis has provided a robust alternative to traditional warfarin treatment. While these recent advances are promising, it is important to acknowledge that the morbidity and mortality associated with atrial fibrillation remains significant. There may be a role for opportunistic screening in patients with relevant symptoms, such as dyspnoea and palpitations, to facilitate early diagnosis and management. However, this would need to be performed within the context of a public health framework and with a rigorous assessment of benefit and risk. Focused efforts to identify specific antidotes for novel oral anticoagulants may herald the dawn of a new era in bleeding reversal to improve management in the acute setting. Additionally, further research to elucidate the mechanisms that relate to initiation and propagation of this common dysrhythmia appears to be of particular relevance to optimise treatment strategies and abrogate adverse risk.

Declarations

Competing Interests

None declared.

Funding

PAP is supported by a British Heart Foundation clinical research training fellowship (FS/15/9/31092). There are no other sources of funding to declare.

Ethical approval

No ethical approval is indicated for this article.

Guarantor

MHT.

Contributorship

PAP and NA are joint first authors. All authors have: (1) made a substantial contribution to the concept and design, acquisition of data or analysis and interpretation of data; (2) drafted the article or revised it critically for important intellectual content; and (3) approved the version to be published.

Acknowledgements

None.

Provenance

Not commissioned; peer-reviewed by James Brophy.

References

- 1.Naccarelli GV, Varker H, Lin J, Schulman KL. Increasing prevalence of atrial fibrillation and flutter in the United States. Am J Cardiol 2009; 104: 1534–1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.European Heart Rhythm Association Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: the task force for the management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart 2010; 31: 2369–2429. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Nault I, Miyazaki S, Forclaz A, Wright M, Jadidi A, Jais P, et al. Drugs versus ablation for the treatment of atrial fibrillation: the evidence supporting catheter ablation. Eur Heart J 2010; 31: 1046–1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haïssaguerre M, Jaïs P, Shah DC, Takahashi A, Hocini M, Quiniou G, et al. Spontaneous initiation of atrial fibrillation by ectopic beats originating in the pulmonary veins. N Engl J Med 1998; 339: 659–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verma A, Jiang CY, Betts TR, Chen J, Deisenhofer I, Mantovan R, et al. Approaches to catheter ablation for persistent atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 1812–1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haïssaguerre M, Sanders P, Hocini M, Takahashi Y, Rotter M, Sacher F, et al. Catheter ablation of long-lasting persistent atrial fibrillation: critical structures for termination. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2005; 16: 1125–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friberg L, Tabrizi F, Englund A. Catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation is associated with lower incidence of stroke and death: data from Swedish health registries. EHJ 2016; 37: 2478–2487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Gelder, Groenveld HF, Crijns HJ, Tuininga YS, Tijssen JG, Alings AM, et al. Lenient versus strict rate control in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2010; 362: 1363–1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marshall HJ, Harris ZI, Griffith MJ, Gammage MD. Atrioventricular nodal ablation and implantation of mode switching dual chamber pacemakers: effective treatment for drug refractory paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Heart 1998; 79: 543–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ganesan AN, Brooks AG, Roberts-Thomson KC, Lau DH, Kalman JM, Sanders P. Role of AV nodal ablation in cardiac resynchronization in patients with coexistent atrial fibrillation and heart failure: a systematic review. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012; 59: 719–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hohnloser SH, Kuck KH, Lilienthal J. Rhythm or rate control in atrial fibrillation—Pharmacological Intervention in Atrial Fibrillation (PIAF): a randomized trial. Lancet 2000; 356: 1789–1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Gelder IC, Hagens VE, Bosker HA, Kingma JH, Kamp O, Kingma T, et al. A comparison of rate control and rhythm control in patients with recurrent persistent atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2002; 347: 1834–1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wyse DG, Waldo AL, DiMarco JP, Domanski MJ, Rosenberg Y, Schron EB, et al. A comparison of rate control and rhythm control in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2002; 347: 1825–1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corley SD, Epstein AE, DiMarco JP, Domanski MJ, Geller N, Greene HL, et al. Relationships between sinus rhythm, treatment, and survival in the atrial fibrillation. Follow-Up Investigation of Rhythm Management (AFFIRM) study. Circulation 2004; 109: 1509–1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gage BF, Waterman AD, Shannon W, Boechler M, Rich MW, Radford MJ. Validation of clinical classification schemes for predicting stroke: results from the National Registry of Atrial Fibrillation. JAMA 2001; 285: 2864–2870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hicks T, Stewart F, Eisinga A. NOACs versus warfarin for stroke prevention in patients with AF: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Heart 2016; 3: e000279–e000279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, Eikelboom J, Oldgren J, Parekh A, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2010; 361: 1139–1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J, Pan G, Singer DE, Hacke W, et al. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2011; 365: 883–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sherwood MW, Nessel CC, Hellkamp AS, Mahaffey KW, Piccini JP, Suh EY, et al. Gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation treated with rivaroxaban or warfarin: ROCKET AF trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015; 66: 2271–2281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Granger CB, Alexander JH, Mcmurray JJ, Lopes RD, Hylek EM, Hanna M, et al. Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2011; 365: 981–992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giugliano RP, Ruff CT, Braunwald E, Murphy SA, Wiviott SD, Halperin JL, et al. Edoxaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2013; 369: 2093–2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Caterina R, Camm AJ. What is ‘valvular’ atrial fibrillation? A reappraisal. Eur Heart J 2014; 35: 3328–3335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chan YH, Kuo CT, Yeh YH, Chang SH, Wu LS, Lee HF, et al. Thromboembolic, bleeding and mortality risks of rivaroxaban and dabigatran in Asians with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016; 68: 1389–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patel MR, Hellkamp AS, Fox KA. Point-of-care warfarin monitoring in the ROCKET AF Trial. N Engl J Med 2016; 374: 785–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cohen D. Manufacturer failed to disclose faulty device in rivaroxaban trial. BMJ 2016; 354: i5131–i5131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laliberte F, Bookhart, Nelson WW, Lefebvre P, Schein JR, Rondeau-Leclaire J, et al. Impact of once-daily versus twice-daily dosing frequency on adherence to chronic medications among patients with venous thromboembolism. Patient 2013; 6: 213–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dorian P, Kongnakorn T, Phatak H, Rublee DA, Kuznik A, Lanitis T, et al. Cost-effectiveness of apixaban vs current standard of care for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J 2014; 35: 1897–1906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pollack CV, Reilly PA, Eikelboom J, Glund S, Verhamme P, Bernstein RA, et al. Idarucizumab for dabigatran reversal. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 511–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reddy VY, Doshi SK, Sievert H, Buchbinder M, Neuzil P, Huber K, et al. Percutaneous left atrial appendage closure for stroke prophylaxis in patients with atrial fibrillation: 2.3-year follow-up of the PROTECT AF (Watchman left atrial appendage system for embolic protection in patients with atrial fibrillation) trial. Circulation 2013; 127: 720–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holmes DR, Kar S, Price MJ, Whisenant B, Sievert H, Doshi SK, et al. Prospective randomized evaluation of the Watchman left atrial appendage closure device in patients with atrial fibrillation versus long-term warfarin therapy: the PREVAIL trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 64: 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]