Abstract

Background:

The aim of our study was to determine the influence of routine ketone monitoring on hyperglycemic events (HE) and ketosis in youngsters with type 1 diabetes (T1D).

Methods:

Our single-site, controlled and randomized study was conducted on children and adolescents with T1D outside of remission phase. During two crossover periods of 6 months, patients (n = 22) experiencing HE tested ketones alternatively with a blood ketone meter or urine ketone test strips and gave their opinion on screening methods after completion of clinical trial. Moreover, we evaluated levels of awareness of ketone production in a series of 58 patients and sometimes parents via a multiple-choice questionnaire.

Results:

Based on self-monitoring data, patients experienced a mean of 4.8 HE/month (range 0–9.3). Patients performed accurate ketone tests more frequently during urine (46%) than during blood-testing (29%) periods (p < 0.05); while globally, 50% of ketone tests were inaccurate (i.e. without HE). Ketosis occurred significantly more often during urine (46.4%) than during blood (14.8%) monitoring (p = 0.01), although no episodes of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) were noticed. Duration of hyperglycemia was not different whether patients measured ketones or not, suggesting that ketone monitoring did not affect correction of glycemia. Patients evaluated blood monitoring more frequently as being practical, reliable, and useful compared with urine testing. Scores in the awareness questionnaire were globally low (36.8%) without difference between patients and their parents.

Conclusions:

Although our study shows differences in outcomes (e.g. accurate use, detection of ketosis) of urine versus blood ketone monitoring, these did not affect the occurrence of HE. Whereas ketone monitoring is part of standardized diabetes education, its implementation in daily routine remains difficult, partly because patient awareness about mechanisms of ketosis is lacking.

Keywords: children, ketoacidosis, ketone, questionnaire, self-monitoring, type 1 diabetes

Introduction

Type 1 diabetes (T1D) incidence is consistently rising, especially in children below the age of 5 [Lipman et al. 2013]. Among the acute complications related to the disease, diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) is the most important and is associated with a mortality rate of 0.15–0.30% [Rosenbloom, 2010], mostly (57–87%) due to cerebral edema [Wolfsdorf et al. 2006]. Other causes of death with DKA include hypokalemia (risk of cardiac arrhythmias), hypophosphatemia, hypoglycemia, peripheral venous thrombosis, acute renal failure, sepsis, or aspiration pneumonia [Rosenbloom, 2010; Wolfsdorf et al. 2009]. Estimation of the annual incidence of DKA in patients with T1D outside of partial remission phase varies between 1.5 to 8 episodes per 100 patients [Rewers et al. 2002]. Risk factors for DKA include poor diabetes control or compliance with insulin injections, sick days and errors in manipulation (e.g. insulin pump therapy) [Rosenbloom, 2010]. As DKA is physiologically always preceded by the production of ketone bodies (i.e. acetoacetate and 3β-hydroxybutyrate), strategies aiming at reducing the occurrence of ketosis events may have a direct impact on the global reduction of DKA incidence. Besides DKA, diagnosis of ketosis may influence diabetes outcome as suggested by investigations showing the activation by ketones of oxidative stress via mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways, with possible implications in vascular disease and atherosclerosis [Kanikarla-Marie and Jain, 2016].

Ketone testing traditionally depends on urine collection, which might prove difficult to implement in young children. An alternative has been developed for testing ketones in capillary blood, and recent meters now allow accurate monitoring, especially below values of 5 mmol/L of 3β-hydroxybutyrate [Byrne et al. 2000]. Blood ketone testing offers the advantage of early detection of ketone production as compared with urine testing. Also, ketones are cleared faster in blood than urine, which may potentially lead to misinterpretation or overtreatment when controlling ketonuria [Misra and Oliver, 2015]. Recently, a systematic review of literature evidenced that blood ketone monitoring in pediatric patients with T1D was superior to urine testing in reducing emergency room visits, hospitalization and time to recover from DKA [Klocker et al. 2013].

In our study, we want to examine in more depth the potential of blood versus urine ketone monitoring to decrease the frequency and/or the duration of ketosis events (defined as detection of ketone bodies in blood or urine during prolonged hyperglycemia) and the occurrence of DKA in the daily follow up of pediatric patients with T1D. Alternatively, we want to determine whether blood versus urine ketone monitoring decreases the duration of hyperglycemic events (HE) and possibly glycated hemoglobin (HbA1C). We believe these questions might provide important clues concerning the management of HE in children with T1D.

Material and methods

The study was designed as a controlled and randomized intervention clinical trial in children and adolescent with T1D attending an outpatient clinic in a tertiary health care center (Cliniques Universitaires Saint Luc). Informed consent was obtained from the parents and assent was obtained from children after receiving adapted information. The local ethical committee approved the study protocol. The intervention corresponded to two periods of ambulatory ketone body measurements performed by patients (or their parents) using either a blood ketone meter (GlucoMen LX Plus, A. Menarini Diagnostics Ltd., Belgium) or urine ketone test strips (Keto-Diabur-Test® 5000, Roche, France) during two consecutive periods of 6 months (total duration of 12 months). A crossover was performed for each patient after 6 months to switch from the blood (group A) to the urine (group B) testing group or vice versa. Patients were randomized to enter the study into group A or B. Patients were asked to check their capillary blood glucose regularly (minimum five times/day, using the GlucoMen LX Plus meter) and to monitor ketone production during every HE. Education for identification and recording of HE, and for the measurement of blood or urinary ketones was provided at the first visit of the trial after randomization and continuously during each follow-up visit (occurring every 3 months). We asked patients to test the presence of ketone bodies during HE, that is, when blood (capillary) glucose was ⩾250 mg/dl (13.9 mmol) after two consecutive glucose measurements separated by a minimum of 2 hours [Wolfsdorf et al. 2009].

Inclusion criteria were as follows: age at trial onset between 5 and 18 years, diagnosis of T1D according to the ISPAD 2014 guidelines [Couper et al. 2014], T1D outside of partial remission phase (defined according to the IDAA1C definition [Steffes et al. 2003; Pecheur et al. 2014], being equal to HbA1C (%) + [4 × insulin dose (units per kilogram per 24 hours)] and ⩾2 years after T1D diagnosis (defined as the first day of insulin therapy). Criteria for exclusion were: patients with non-T1D, history of DKA or severe hypoglycemia, or specific comorbidities as severe neonatal asphyxia (defined as Apgar score 3 or less after 5 minutes), children born small for gestational age, chronic systemic disease, active malignancy, hypothyroidism, hypopituitarism, developmental delay, bladder dysfunction, obesity, carnitine deficiency, β-oxidation defect, or intake of drugs interfering with insulin sensitivity (e.g. corticosteroids or human recombinant growth hormone).

Initial evaluation at baseline included determination of age, sex, anthropometrics (height, weight, and BMI Z score, estimated according to Belgian Flemish reference charts), duration of T1D, diabetes-related comorbidities, general physical evaluation and screening of HbA1C. Patients were followed up every 3 months for clinical assessment (including blood pressure and anthropometrics) and to record self-monitoring data, ketosis and HE, DKA episodes, daily insulin requirements and HbA1C levels, and symptoms or signs of chronic hyperglycemia. Once during the study period, patients were tested for lipid profile, antitransglutaminase IgA, thyroid function tests and antibodies, ionogram, hemogram, albuminuria and retinopathy. Adaptation of patients’ insulin therapy, being either multiple daily injection (MDI) regimens or insulin pump therapy, was based on the institution’s guidelines.

The primary study endpoint was the evaluation of the number of ketosis events, including DKA (defined as hyperglycemia ⩾ 200 mg/dl and pH < 7,3 with or without bicarbonate < 15 mmol/L) during outpatient follow up in our center at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months after trial onset. The secondary endpoint was to evaluate the duration of hyperglycemia during HE based on self-monitoring data, as measured at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months after trial onset. At the end of the study period, patients were asked to give their opinion on the two methods investigated for ketone monitoring, based on items defined as ‘practical’, ‘reliable’, ‘useful’, ‘reassuring’ or ‘restrictive’, with levels of validation ranging from ‘not at all’ to ‘a lot’ (Table 2).

Table 2.

Questionnaire about opinion on urine versus blood ketone testing.

| Opinion on urine ketone testing |

Opinion on blood ketone testing |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| –2 | –1 | 0 | +1 | +2 | –2 | –1 | 0 | +1 | +2 | |

| Constraining | 0 | 18.2 | 18.2 | 36.4 | 18.2 | 55.6 | 11.1 | 22.2 | 11.1 | 0 |

| Practical* | 27.3 | 27.3 | 0 | 36.4 | 9.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 22.2 | 77.8 |

| Reliable* | 0 | 0 | 16.7 | 41.7 | 33.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12.5 | 88.9 |

| Useful* | 0 | 0 | 0 | 27.3 | 72.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| Reassuring | 0 | 0 | 10 | 30 | 50 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 20 | 70 |

Data were expressed as percentages. −2, not at all; −1, not really; 0, indifferent; +1, a little; +2, a lot. *p < 0.05, compared urine versus blood ketone testing.

In parallel to the intervention trial, we submitted to patients with T1D a questionnaire, called the Aware about KEtone TESTing (AKETEST) questionnaire (Table 3), about awareness in mechanisms leading to ketone body production and in the attitudes that may prevail to prevent or manage ketosis or DKA. The eligibility criteria for the questionnaire study were identical to those used in the ketone testing intervention trial. Patients anonymously answered the questionnaire in separate rooms and outside of the consultation room (to avoid the intervention from healthcare professionals) and were invited to choose to reply either alone or with their parents, or to let their parents reply alone.

Table 3.

Scores of the aware-about-ketone-testing (AKETEST) questionnaire.

| Total (n = 58) |

Patients |

Parents |

Family |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | % | % | % | |

| (A) The frequency (incidence) of DKA is: | ||||

| Extremely rare (never seen in your hospital) | 4 (6.9) | 50 ± 51.4 | 44 ± 50.7 | 28.6 ± 46.9 |

| Rare (few cases in your hospital) | 11 (18.9) | |||

| Presented only by some patients (≈1 episode/year) | 23 (39.6) | |||

| Recurrent in some patients (≈3 episodes/year) | 19 (32.7) | |||

| Frequent in some patients (≈1 episode/month) | 3 (5.2) | |||

| (B) DKA is best taken care of at: | ||||

| Home with people experienced in diabetes | 20 (34.5) | 77.8 ± 42.8 | 64 ± 48.9 | 64.3 ± 49.7 |

| Hospital by a specialized team | 39 (67.2) | |||

| (C) DKA originates from: | ||||

| A current disease (infection, virus, gastroenteritis) | 5 (8.6) | 31.5 ± 26.7 | 41.3 ± 22.1 | 33.3 ± 18.5 |

| A lack of insulin (oversight, doses too low, …) | 30 (51.7) | |||

| An overdose of insulin | 1 (1.7) | |||

| A reactivation of diabetes | 4 (6.9) | |||

| A current hyperglycemia | 22 (37.9) | |||

| An accumulation of ketones | 28 (48.3) | |||

| An unknown origin | 0 | |||

| (D) DKA may be favored by: | ||||

| Patient’s age | 11 (18.9) | 22.2 ± 6.5 | 24 ± 15.3 | 21.4 ± 16.6 |

| Patient’s gender | 5 (8.6) | |||

| The type of insulin therapy | 18 (31) | |||

| Treatment compliance (diet/injections/sport) | 30 (51.7) | |||

| The number of glucose checks per day | 4 (6.9) | |||

| The number of consultations per year | 0 | |||

| The presence of eating disorders | 8 (13.8) | |||

| Alcohol consumption | 2 (3.4) | |||

| Others | 1 (1.7) | |||

| (E) DKA may be prevented by: | ||||

| Dietary modifications | 3 (5.2) | 40.7 ± 31.4 | 46.7 ± 34.7 | 54.8 ± 28.1* |

| Practicing sports | 4 (6.9) | |||

| Extra insulin administration (corrections, supplemental insulin injection) | 24 (41.4) | |||

| Control of glycemias | 16 (27.6) | |||

| Control of ketones (urine or blood) during each hyperglycemia (>250 mg/dl or 14 mmol) | 9 (15.5) | |||

| Control of ketones (urine or blood) after 2 consecutive hyperglycemias (>250 mg/dl or 14 mmol) | 36 (62.1) | |||

| No specific measures | 1 (1.7) | |||

| (F) The presence of ketones in blood or urine: | ||||

| Is normal during some periods of the day | 3 (5.2) | 29.6 ± 15.7 | 38.7 ± 24.9 | 35.7 ± 34.5* |

| Depends on diet/food intake | 9 (15.5) | |||

| Is due to sports practicing | 1 (1.7) | |||

| Suggests a lack of insulin | 47 (81) | |||

| Suggests an overdose of insulin | 3 (5.2) | |||

| Suggests the patient has an infection | 9 (15.5) | |||

| (G) The presence of ‘+++’ in the urine ketone test or >3 mmol in the blood ketone test indicates: | ||||

| That the patient is fasting (did not eat) | 1 (1.7) | 43.1 ± 26.9 | 38 ± 28.9 | 39.3 ± 23.4 |

| That the patient needs to eat | 1 (1.7) | |||

| That the insulin dose needs to be increased | 29 (50) | |||

| That the insulin dose needs to be decreased | 0 | |||

| That the patient should be presented at the emergency ward | 27 (46.5) | |||

| That the parents/patient should call the doctor on call | 11 (18.9) | |||

| That a glucose check needs to be performed | 17 (29.3) | |||

| That a control of ketones needs to be performed | 28 (48.3) |

p < 0.05, compared family versus patients; family = patients + parents.

Data were analyzed using the GraphPad software. Categorical variables were analyzed using the chi-square test and continuous variables were analyzed using chi-square trend test, unpaired t test or Mann–Whitney U test, according to the statistical distribution. Data were submitted to D’Agostino and Pearson omnibus normality test and Levene’s test for equality of variances. ANOVA with R tests were used when there were more than two groups. Multiple comparisons were subsequently conducted when significant. Changes over time were compared using Student paired t test. Data were expressed as means and standard deviations. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Results

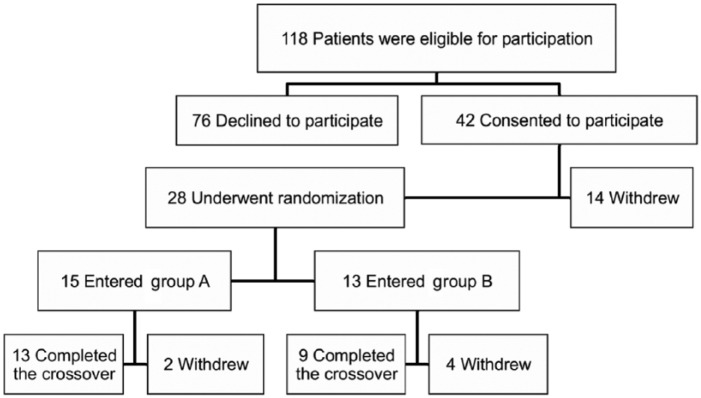

In a total of 118 patients with T1D that met the inclusion criteria in our center, 42 (35%) consented to participate (written informed consent provided by a parent or guardian) and 28 underwent randomization (Figure 1). Patients initiated the study with either blood testing for 6 months (group A) or urine testing for 6 months (group B). At the end of the study, 22 patients (19%) completed the crossover. Patients who stopped the study estimated the follow up of the study as being too difficult (constraining) (86%), or reported a lack of interest in ketone values (14%) or the oversight of ketone tests (43%). Our clinical series is characterized by patients aged 11.4 years on average, with gender ratio of 0.4 (F/M ratio), duration of T1D of 4.9 ± 1.9 years and mean HbA1C of 7.6% at trial onset (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Study enrollment and treatment of the patients.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the clinical series at study onset.

| Study (n = 22) |

Questionnaire (n = 58) | p * | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | 0.75 | ||

| Girls | 9 (40.9) | 26 (44.8) | |

| Boys | 13 (59.1) | 32 (55.2) | |

| Age, year | |||

| Mean | 11.4 ± 2.8 | 12.9 ± 2.9 | 0.02 |

| Median | 11.5 | 13 | |

| Range | 7–16 | 5–18 | |

| HbA1C (%) | 7.6 ± 1.1 | ND | |

| HbA1C (mmol/l) | 59.6 | ||

| Diabetes duration, year | 4.9 ± 1.9 | 6.6 ± 3.0 | 0.007 |

| Self-monitoring$ | 5.6 ± 1.4 | ND | |

| Height Z score | 0.0 ± 0.9 | ND | |

| BMI Z score | 0.2 ± 0.9 | ND |

Categorical variables were analyzed using chi-square test; continuous variables were analyzed using chi-square test with trend; ages at diagnosis and diabetes duration were analyzed using unpaired t test. $Self-monitoring was defined as number of blood glucose monitoring performed per day. Plus-minus values are means ± SD. ND, not determined; HbA1C, glycated hemoglobin; SD, standard deviation.

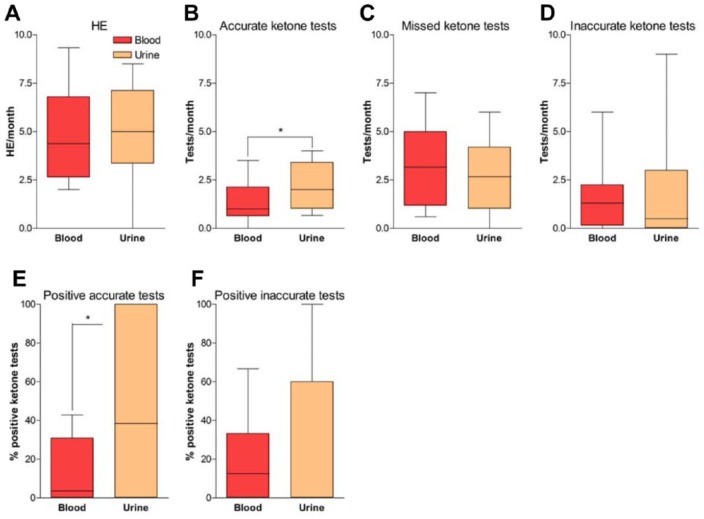

During the whole study period and based of self-monitoring data, patients experienced 4.8 ± 2.5 HE/month (range 0–9.3) without difference between group A or B (Figure 2A). Ketone body production was adequately monitored 1.8 times/month on average (Figure 2B), which corresponds to 37% of HE being controlled for ketosis. Patients using blood monitoring (group A) controlled HE significantly less (1.4 ± 1.1 times/month) than while performing urine testing (group B, 2.2 ± 1.2 times/month, p < 0.05). However, no difference was observed in the propensity of patients from group A or B to miss ketone monitoring during HE (Figure 2C). Besides missing ketone monitoring during most HE, patients also checked their ketones inaccurately 1.5 ± 1.6 times/month while in group A, and 1.8 ± 2.8 times/month during follow up in group B (Figure 2D). This happened when ketones were tested while blood glucose was within normal range (60–180 mg/dl being our range for random glycemia, including postprandial) or when patients experienced a nonrecurrent hyperglycemia (peak blood glucose > 180 mg/dl without abnormal consecutive control) or a recurrent hyperglycemia between 180 and 250 mg/dl.

Figure 2.

Outcome measurement of hyperglycemic events and ketone testing.

Graphs show differences between blood and urine ketone testing groups in numbers of hyperglycemic event (HE)/month (A), numbers of accurate ketone tests/month (B), numbers of missed ketone tests/month (C), numbers of inaccurate ketone tests/month (D), percentage of positive ketone tests during accurate testing (E) and percentage of positive ketone tests during inaccurate testing (F). Blood ketone testing group (group A) is shown in red and urine ketone testing group (group B) is shown in orange. *p < 0.05 compared blood versus urine ketone testing.

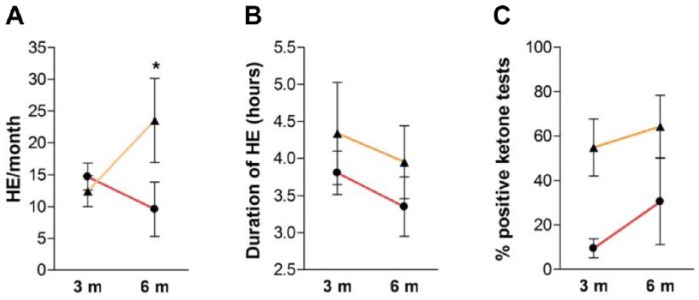

When ketones were monitored adequately, they were globally positive (i.e. blood ketones ⩾ 0.6 mmol/L and urine ketones ⩾ ‘+’) during 30% of HE. Interestingly, ketone analyses were more frequently positive in patients from group B (46.4%) than from group A (14.8%) (p = 0.01) (Figure 2E). When positive, blood ketone body production was calculated at levels of 1.4 ± 1.2 mmol/L in group A, while patients in group B reported 50% of ‘++’ and 41% of ‘+’ after urine testing. Furthermore, when ketones were controlled outside of HE, there was only a trend toward higher positivity after urine testing (27.6 ± 39.5% versus 16.6 ± 21.2% positive tests, respectively, in group B and A) (Figure 2F). In this case, levels of ketones were not significantly different from those observed during adequate control (1.4 ± 1.1 mmol/L for ketonemia and 24% of ‘++’ for ketonuria). Proportion of severe ketosis (⩾3 mmol/L for blood [Savage et al. 2011; Wolfsdorf et al. 2014] and ‘+++’ for urine tests) was similar between the two groups (4% for urine and 5% for blood monitoring). During the study period, patients did not significantly modify their levels of self-monitoring and tested blood glucose 5.6 ± 1.4 times/day at trial onset, 5.5 ± 1.3 times/day after 6 months and 5.4 ± 1.4 times/day (p = 0.45) after 12 months. Also, no difference was noticed in mean blood glucose or HbA1C levels before (7.6 ± 1.1%) and after (7.5 ± 0.9%, p = 0.40) the study period. During the study period, changes occurred in numbers of HE/month after 3 and 6 months of follow-up and were significantly lower in group A (9.6 ± 1.1) than in group B (23.5 ± 11.5, p < 0.05) after completion of each crossover period (Figure 3A). Also, there was a trend toward a decrease of HE duration from 3 to 6 months during follow up in both groups (Figure 3B, not significant) and a trend toward an increased rate of ketosis observed after blood ketone testing after 6 months (Figure 3C, not significant).

Figure 3.

Evolution of hyperglycemic event and ketone-testing parameters throughout study.

Graphs show evolution of numbers of hyperglycemic event (HE)/month (A), duration of HE (B) and percentage of positive ketone tests (C) at 3 months (3 m) and 6 months (6 m) after initiation of either group A (red lines) or group B (orange lines). Results are shown as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05 compared blood versus urine ketone testing at 6 months.

After completion of the crossover study, patients were asked to answer a questionnaire (Table 2) about their opinion on blood versus urine monitoring. For urine ketone testing, patients reported 25.5% of negative opinion (−2 and −1), 65.5% of positive opinion (+1 and +2) with 52.8% being very positive (+2), and 9% of neutral opinion (0). Most patients answering the questionnaire evaluated urine tests as very useful (72.7%) while only 33.3% found it very reliable. For blood ketone testing, no patients reported a negative opinion: 91.8% had a positive opinion (+1 and +2) with 85.7% being very positive (+2) and 8.2% had a neutral opinion (0). Most patients answering the questionnaire found blood tests very reliable (88.9%) and all patients found it very useful (100%). In the opinion questionnaire, ‘practical’, ‘reliable’ and ‘useful’ were the three items ranked significantly more positively in blood compared with urine testing (p < 0.05).

In parallel to the crossover study, we asked 58 patients to anonymously fill the AKETEST questionnaire to evaluate their awareness about mechanisms of ketone production and related clinical implications (Table 3). Scores were analyzed globally or separately in subgroups (patients alone, parents alone or patients + parents together). Global questionnaire score was 36.8% and among the 567 answers provided, 72% were correct without difference between patients (73.1%) or parents (71%). No differences were found in scores of patients alone (35.8 ± 16%) as compared with parents alone (37.8 ± 15.3%, p = 0.34) or to patients + parents (36.1 ± 13.6%, p = 0.48). Furthermore, a similar percentage of questions without any correct answers was observed among subgroups (21.4 ± 16.8%, 25.1 ± 15.6% and 22.4 ± 24.5% respectively for patients alone, parents alone and patients + parents, p = 0.41). Highest scores were obtained in question B by patients alone (77.8 ± 42.8%) although without being significantly different from those of parents alone (64 ± 48.9%, p = 0.17) or patients + parents (64.3 ± 49.7%, p = 0.49). Contrarily, lowest scores were obtained in question D without noticeable differences among subgroups (global score of 22.5%). Patients + parents scored higher than patients alone in questions E and F, regarding respectively, DKA prevention and factors favoring ketosis (Table 3). When analyzing individual items, two answers were scored differently among subgroups: patients evaluated more correctly than parents the influence of insulin therapy on the occurrence of DKA (55% versus 22.7%, p = 0.03), whereas parents, but not patients alone, identified infection as being associated with ketone production (respectively 36% versus 0%, p = 0.01).

Discussion

Our single-site study was performed in a series of patients with T1D under multiple daily injection (MDI) or insulin pump therapy that showed acceptable adherence to diabetes treatment with regards to self-monitoring and HbA1C levels. Indeed, the average HbA1C levels throughout the study period were estimated at 7.5% (median: 7.5%), corresponding to the limit of therapeutic targets of <7.5% according to ISPAD guidelines [Donaghue et al. 2007]. Also, 50% of patients had HbA1C levels below 7.5% at trial onset, which is in concordance with results from the Prospective Diabetes Follow-up Registry (DPV) in Germany and Austria [Maahs et al. 2014].

Patients from our series experienced an average of 4.8 HE/month, that is, at least one prolonged hyperglycemia occurring every week. We observed that the duration of hyperglycemia during HE was not different when patients measured ketones or not (respectively, 3.8 ± 2.5 versus 3.6 ± 2.2 hours, p = 0.26), meaning that the education patients received about ketone monitoring did not modify their propensity to correct hyperglycemia. When monitored accurately, 30% of HE were associated with ketosis (>1 ketosis/patient/month) with similar levels of ketonemia and ketonuria if we consider the correlation made by Taboulet and colleagues [Taboulet et al. 2007] of 1.2 mmol/L blood ketones (3β-hydroxybutyrate) corresponding to ‘++’ urinary ketones (acetoacetate). However, a significantly higher rate of ketosis events was observed during urine (46%) versus blood (15%) testing. By comparison, Laffel and co-workers [Laffel et al. 2006] observed 8% of moderately or largely positive urine ketone tests compared with 4% of positive ketonemia in patients with T1D during sick days. Comparing values of blood and urine ketone tests is difficult because of the nature of ketone bodies (3β-hydroxybutyrate versus acetoacetate), the methods used for measurement, and the kinetics of ketone production and clearance. Although the production of 3β-hydroxybutyrate and acetoacetate is equimolar in the human blood, situations like DKA favor the accumulation of 3β-hydroxybutyrate, with levels reaching up to 10 times those of acetoacetate [Bismuth and Laffel, 2007]. Also, changes in mitochondrial redox state after DKA stimulate the conversion of 3β-hydroxybutyrate to acetoacetate, which then accumulates in the urine [Misra and Oliver, 2015], whereas blood 3β-hydroxybutyrate levels decrease quickly (half-life of ≈90 minutes) after insulin injection [Wallace et al. 2001]. Faster clearance of blood versus urine ketones is thus an important factor to consider while interpreting proportions of ketosis events in our setting.

Reliability of both blood and urine ketone measurements may also be questioned. Although blood ketone levels are considered as being reliable below 3 mmol [Weber et al. 2009], there is a nonlinear relationship for 3β-hydroxybutyrate levels > 5 mmol using blood test strips compared with plasma levels [Yu et al. 2011]. The usefulness of 3β-hydroxybutyrate values as a diagnostic tool for DKA was evaluated in several clinical studies with mitigated results [Misra and Oliver, 2015], although a study on 173 patients admitted to an emergency department reported a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 94% of blood ketone testing for a threshold of 3 mmol 3β-hydroxybutyrate applied to detect DKA [Taboulet et al. 2004]. However, the lack of specificity of ketone monitoring motivated the American Diabetes Association (ADA) to discourage these tests for diagnosing DKA [Arora and Menchine, 2012] that should thus only be considered as being probable when 3β-hydroxybutyrate levels exceed 3 mmol [Guerci et al. 2003; Meas et al. 2005]. In our study, levels of ketonemia during accurate tests ranged from 0.6 to 5.8 mmol (median: 0.9 mmol) and 6% of tests were above 3 mmol (versus 9% of ‘+++’ urine tests), yet without any case of DKA. Interestingly, inaccurate ketone measurements (without prolonged hyperglycemia) during blood and urine testing yielded similar positivity rates and values compared with tests performed during HE. During these normoglycemic ketosis events, no concomitant illness, prolonged fasting or errors in insulin administration were reported.

Our study also revealed the difficulty to provide adequate education and motivation about ketone monitoring to patients with T1D. Indeed, we globally observed a lack of adherence to the study protocol (only 19% of patients completed the study), noncompliance to ketone monitoring during HE (only 37% of which were controlled for ketones) and an important proportion of inappropriate tests (50% of total ketone measurements). Our data about compliance were comparable with those of Laffel and colleagues [Laffel et al. 2006] who reported, in a series of 123 patients aged 3–22 years, a global rate of ketone monitoring of ≈35% after two consecutive hyperglycemia (⩾13.9 mmol/L ). Yet in this study, patients in the blood ketone group were monitoring ketone more often than those in the urine ketone group (90.8% versus 61.3%). By contrast, in our study, patients performed more accurate ketone tests while in group B compared with group A, even though our opinion questionnaire on blood versus urine monitoring showed a higher reliability attributed to blood tests. Indeed, blood testing was globally estimated more positively than urine strips, especially as being more ‘practical’, ‘reliable’, and ‘useful’. Reasons for patients to monitor ketones more adequately with urine than with blood testing were not evaluated in our study. It is thus difficult to estimate whether this could partially be explained by the representation that patients might have of ketones being cleared in the urine, or by the habit of urine testing.

In our study protocol, reliability of blood versus urine ketone monitoring was difficult to assess since ketone measurements were not compared with plasma levels and because patients did not experience DKA, hospitalization, or sick days requiring outpatient visit or phone calls to the diabetes team. Yet after 6 months of each crossover period, we observed significantly less HE occurring per month in group A (9.6 HE/month) compared with group B (23.5 HE/month, p < 0.05). Also, there was a trend toward a decrease of HE duration from 3 to 6 months during follow up in both groups and a trend toward an increased rate of ketosis observed during blood ketone testing after 6 months, though these were not significant. The clinical impact of these data is thus complex to interpret and it contrasts with cost savings induced by blood ketone monitoring in a study of 33 children with T1D admitted for DKA in the intensive care unit and who experienced a drastic (up to 9.5 hours) reduction of ketosis duration when using blood versus urine ketone tests [Vanelli et al. 1999].

Our AKETEST questionnaire was developed to evaluate awareness about incidence, clinical importance, favoring factors and management of DKA with or without ketosis. To our knowledge, validated questionnaires that estimate awareness about ketone monitoring are lacking. In 2010, Mackay and McKnight evaluated knowledge about ketones in 120 adult patients with a mean duration of T1D of 16 years [Mackay and McKnight, 2010]. They observed that only 33% of patients estimated that they would check for ketones during hyperglycemia and that 58% of them reported using neither urine nor blood ketone tests. Our data show low levels of awareness with only 37% of patients answering correctly the AKETEST questionnaire, with few differences among subgroups, except for items requiring higher levels of understanding. Indeed, when parents were involved in questionnaire (parents alone or patients + parents), their subgroups obtained higher scores compared with patients alone for questions regarding DKA prevention and factors favoring ketosis or DKA.

Conclusion

Whereas ketone monitoring is part of standardized diabetes education, its implementation in the daily routine remains difficult with parents and patients lacking awareness about ketone production. Although we did not observe DKA, ketone monitoring did not significantly impact glycemic control in our study. Questionnaires revealed that while patients reported a preference to blood ketone meters, they performed monitoring more accurately with urine tests. Furthermore, knowledge about mechanisms of ketone production and management was globally low, as shown by our AKETEST questionnaire. Further research is necessary to evaluate whether ketone monitoring may impact long-term diabetes control and complications.

Acknowledgments

The study was reviewed and approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Cliniques Universitaires Saint Luc. All study participants, or their legal guardians, provided informed written consent prior to study enrollment.

Footnotes

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: PAL is supported by grants from Belgian Society for Pediatric Endocrinology and Diabetology (BESPEED) and Fonds National de la Recherche Scientifique (FNRS).

Conflict of interest statement: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Contributor Information

Line Goffinet, Pediatric Endocrinology Unit, Cliniques Universitaires Saint Luc, Brussels, Belgium.

Thierry Barrea, Pediatric Endocrinology Unit, Cliniques Universitaires Saint Luc, Brussels, Belgium.

Véronique Beauloye, Pediatric Endocrinology Unit, Cliniques Universitaires Saint Luc, Brussels, Belgium.

Philippe A. Lysy, Pediatric Endocrinology Unit, Cliniques Universitaires Saint Luc, Pôle PEDI, Institut de Recherche Expérimentale et Clinique, Université Catholique de Louvain, Avenue Hippocrate 10, B-1200 Brussels, Belgium.

References

- Arora S., Menchine M. (2012) The role of point-of-care beta-hydroxybutyrate testing in the diagnosis of diabetic ketoacidosis: a review. Hosp Pract (1995) 40: 73–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bismuth E., Laffel L. (2007) Can we prevent diabetic ketoacidosis in children? Pediatr Diabetes 8: 24–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne H., Tieszen K., Hollis S., Dornan T., New J. (2000) Evaluation of an electrochemical sensor for measuring blood ketones. Diabetes Care 23: 500–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couper J., Haller M., Ziegler A., Knip M., Ludvigsson J., Craig M., et al. (2014) ISPAD clinical practice consensus guidelines 2014. Phases of type 1 diabetes in children and adolescents. Pediatr Diabetes 15: 18–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaghue K., Chiarelli F., Trotta D., Allgrove J., Dahl-Jorgensen K. and International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes. (2007) ISPAD clinical practice consensus guidelines 2006–2007. Microvascular and macrovascular complications. Pediatr Diabetes 8: 163–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerci B., Benichou M., Floriot M., Bohme P., Fougnot S., Franck P., et al. (2003) Accuracy of an electrochemical sensor for measuring capillary blood ketones by fingerstick samples during metabolic deterioration after continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion interruption in type 1 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 26: 1137–1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanikarla-Marie P., Jain S. (2016) Hyperketonemia and ketosis increase the risk of complications in type 1 diabetes. Free Radic Biol Med 95: 268–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klocker A., Phelan H., Twigg S., Craig M. (2013) Blood beta-hydroxybutyrate vs. urine acetoacetate testing for the prevention and management of ketoacidosis in type 1 diabetes: a systematic review. Diabet Med 30: 818–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laffel L., Wentzell K., Loughlin C., Tovar A., Moltz K., Brink S. (2006) Sick day management using blood 3-hydroxybutyrate (3-OHB) compared with urine ketone monitoring reduces hospital visits in young people with T1DM: a randomized clinical trial. Diabet Med 23: 278–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipman T., Levitt Katz L., Ratcliffe S., Murphy K., Aguilar A., Rezvani I., et al. (2013) Increasing incidence of type 1 diabetes in youth: twenty years of the Philadelphia pediatric diabetes registry. Diabetes Care 36: 1597–1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maahs D., Hermann J., DuBose S., Miller K., Heidtmann B., DiMeglio L., et al. (2014) Contrasting the clinical care and outcomes of 2,622 children with type 1 diabetes less than 6 years of age in the united states T1D exchange and German/Austrian DPV registries. Diabetologia 57: 1578–1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackay L., McKnight J. (2010) Ketone knowledge among people with type 1 diabetes. Journal of Diabetes Nursing 14: 304–307. [Google Scholar]

- Meas T., Taboulet P., Sobngwi E., Gautier J. (2005) Is capillary ketone determination useful in clinical practice? In which circumstances? Diabetes Metab 31: 299–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misra S., Oliver N. (2015) Utility of ketone measurement in the prevention, diagnosis and management of diabetic ketoacidosis. Diabet Med 32: 14–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pecheur A., Barrea T., Vandooren V., Beauloye V., Robert A., Lysy P. (2014) Characteristics and determinants of partial remission in children with type 1 diabetes using the insulin-dose-adjusted A1C definition. J Diabetes Res 2014: 851378. doi: 10.1155/2014/851378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rewers A., Chase H., Mackenzie T., Walravens P., Roback M., Rewers M., et al. (2002) Predictors of acute complications in children with type 1 diabetes. JAMA 287: 2511–2518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbloom A. (2010) The management of diabetic ketoacidosis in children. Diabetes Ther 1: 103–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage M., Dhatariya K., Kilvert A., Rayman G., Rees J., Courtney C., et al. (2011) Joint British Diabetes Societies guideline for the management of diabetic ketoacidosis. Diabet Med 28: 508–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffes M., Sibley S., Jackson M., Thomas W. (2003) Beta-cell function and the development of diabetes-related complications in the Diabetes Control And Complications Trial. Diabetes Care 26: 832–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taboulet P., Deconinck N., Thurel A., Haas L, Manamani J., Porcher R., et al. (2007) Correlation between urine ketones (acetoacetate) and capillary blood ketones (3-beta-hydroxybutyrate) in hyperglycaemic patients. Diabetes Metab 33: 135–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taboulet P., Haas L., Porcher R., Manamani J., Fontaine J., Feugeas J., et al. (2004) Urinary acetoacetate or capillary beta-hydroxybutyrate for the diagnosis of ketoacidosis in the emergency department setting. Eur J Emerg Med 11: 251–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanelli M., Chiari G., Ghizzoni L., Costi G., Giacalone T., Chiarelli F. (1999) Effectiveness of a prevention program for diabetic ketoacidosis in children. An 8-year study in schools and private practices. Diabetes Care 22: 7–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace T., Meston N., Gardner S., Matthews D. (2001) The hospital and home use of a 30-second hand-held blood ketone meter: guidelines for clinical practice. Diabet Med 18: 640-645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber C., Kocher S., Neeser K., Joshi S. (2009) Prevention of diabetic ketoacidosis and self-monitoring of ketone bodies: an overview. Curr Med Res Opin 25: 1197–1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfsdorf J., Allgrove J., Craig M., Edge J., Glaser N., Jain V., et al. (2014) ISPAD clinical practice consensus guidelines 2014. Diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state. Pediatr Diabetes 15: 154–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfsdorf J., Craig M., Daneman D., Dunger D., Edge J., Lee W., et al. (2009) Diabetic ketoacidosis in children and adolescents with diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes 10: 118–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfsdorf J., Glaser N., Sperling M. and American Diabetes Association. (2006) Diabetic ketoacidosis in infants, children, and adolescents: a consensus statement from the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 29: 1150–1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H., Agus M., Kellogg M. (2011) Clinical utility of Abbott Precision Xceed Pro® ketone meter in diabetic patients. Pediatr Diabetes 12: 649–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]