Summary

Interethnic differences exist in the distribution of serum lipids, with African Americans (AA) generally having a healthier lipid profile than other US ethnic groups. Similar lipid distributions are observed among other African ancestry groups with distinct lifestyle characteristics, suggesting the importance of inherited factors. Despite healthier serum lipids, AA experience a disproportionate burden of Type 2 Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease. As evidence of a different relationship between serum lipids and disease exists, the characterization of metabolic risk using lipid concentration (as in Metabolic Syndrome criteria) may lead to the under-identification of AA at risk. Given the disproportionately high rate of metabolic disorders in AA, understanding interethnic differences in the association between serum lipids and disease should be a research priority, as better appreciation of these differences will enhance knowledge of disease etiology, improve intervention targeting, and may lead to mechanisms to ameliorate debilitating health disparities in the US and globally.

Keywords: African American, lipids, epidemiology, health disparities, genomics, metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance

INTRODUCTION

The association between serum lipids and disease risk is well-established, with dyslipidemia commonly observed to be associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD), but this association differs between ethnic groups. It is clear that there is further complexity in this relationship among African Americans (AA), who have, on average, a more favorable lipid profile compared to European Americans (EA), yet they do not experience an associated decrease in diseases that are expected to be responsive to reduction in this key risk factor: AA have an increased risk of CVD mortality [1,2] and a 2-fold higher prevalence of T2D than EA [3]. This observation leads to many important questions, which are addressed in this review: What are the environmental, physiological, and genetic factors that explain the interethnic differences in serum lipids? What are the implications of these interethnic differences for disease development and identification? We present epidemiological evidence for the interethnic differences, explore data on a range of factors that could play a role in this difference, and evaluate the effects, from molecular to societal, that this variability may have on the disproportionate burden of metabolic disorders seen in AA.

Ethnic difference in the distribution of serum lipid parameters has been observed widely, with triglyceride (TG) consistently found to be significantly lower and high-density lipoprotein (HDL-C) to be higher in AA compared to other ethnic groups in the US. This difference can be seen in NHANES, a dataset designed to be representative of the US population: mean TG was 113, 143, and 158 mg/dl in AA, EA, and Mexican Americans (MA), respectively, and mean HDL-C was 54, 50, and 47 mg/dl in AA, EA, and MA, respectively [4]. Notably, interethnic differences have been observed in children, providing compelling evidence that this difference is unlikely to be explained completely by variation in environmental factors by ethnicity. Among children, low-density lipoprotein (LDL-C) was 5.6 mg/dl lower, TG was 15.7 mg/dl lower, and HDL-C was 4.7 mg/dl higher in AA compared to non-AA (predominantly EA) [5]. These differences are also manifest in the prevalence of dyslipidemia in NHANES children and adolescents: the prevalence of high TG and low HDL-C in AA was less than half that of EA (the prevalence of high TG in MA was similar to EA, and low HDL-C was intermediate) [6]. Similar results have been reported in other analyses [7–9]. In addition to differences in serum lipid concentrations, interethnic variation in lipoprotein particle size has been observed, with a less atherogenic distribution (larger HDL and LDL, and smaller VLDL particles) in those of African ancestry [8,10,11]. Disentangling the determinants of these interethnic differences is incredibly complex in the face of the variability in a wide range of potential factors, from the molecular to the societal level.

WHY IS THERE AN INTERETHNIC DIFFERENCE?

Environmental Factors

Lifestyle factors are often hypothesized to contribute to interethnic differences in health outcomes. However, speculation about the contribution of these factors to the interethnic differences in serum lipids must be tempered by observations in West Africans (WA), the descendents of the ancestral population of AA. The comparison of large datasets of AA and WA designed by the same researcher with data collected using the same questionnaires (with culturally-relevant adjustments) is useful at this point. Characteristics of AA (further description [12]) and WA (further description [13]) is provided, along with similar data on NHANES (further description [14,15]) EA and AA (Table 1). The importance of a lifestyle factor as a key determinant of interethnic differences in serum lipids appears unlikely given the presented data. Both alcohol intake and smoking habits are widely different in WA and AA, with AA more closely resembling EA, however, mean TG remains low in all African ancestry groups.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of Smoking, Alcohol Intake, HDL-C, and TG in African Americans, West Africans, and European Americans

| Cohort | West Africans (WA) AADM |

African Americans (AA) HUFS |

African Americans (AA) NHANES |

European Americans (EA) NHANES |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| N | 618 | 879 | 602 | 937 | 160 | 166 | 431 | 428 |

| Age (Yrs) | 40.4 ± 15.7 | 40.7 ± 14.2 | 43.6 ± 13.0 | 43.0 ± 13.7 | 45.3 ± 16.2 | 44.9 ± 16.0 | 49.2 ± 16.9 | 50.5 ± 15.9 |

| Current Smoker (%) | 8% | 2% | 61% | 44% | 39% | 21% | 28% | 24% |

| Former Smoker (%) | 19% | 1% | 12% | 12% | 19% | 14% | 33% | 26% |

| Regular Alcohol Intake (%) | 69% | 53% | 80% | 69% | 83% | 45% | 85% | 66% |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.7 ± 4.2 | 27.0 ± 6.4 | 28.5 ± 7.3 | 31.4 ± 8.8 | 27.7 ± 5.3 | 30.5 ± 7.7 | 28.1 ± 5.6 | 27.5 ± 6.4 |

| HDL-C(mg/dl) | 41.1 ± 13.5 | 44.1 ± 14.6 | 51.4 ± 15.5 | 55.3 ± 15.5 | 53.6 ± 13.9 | 63.7 ± 15.3 | 47.7 ± 11.8 | 59.0 ± 15.0 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 86.5 ± 41.0 | 80.7 ± 34.0 | 104.7 ± 60.0 | 94.8 ± 51.1 | 100.9 ± 51.2 | 84.8 ± 44.1 | 133.5 ± 67.3 | 121.6 ± 60.7 |

Shown are means ± standard deviations, or percentages

AADM: The Africa America Diabetes Mellitus Study

HUFS: Howard University Family Study

NHANES: The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

Socioeconomic status and education level, which are lower in AA compared to EA, could be hypothesized to adversely affect lipid levels. Nevertheless, in nationally representative samples (NHANES), careful adjustment for socioeconomic and educational factors did not alter the observed interethnic differences in serum lipids [16,17]. Similarly, data support a poorer diet quality in AA compared to EA, [18–21] which would be anticipated to cause worse lipid values in AA. Physical activity is also known to influence serum lipid concentrations, and a consistent pattern of higher physical activity in AA could be expected to lead to a healthier lipid profile. However, physical activity measures, as determined by accelerometry, are comparable between AA and EA adults in NHANES [22,23]. Interethnic differences in the lipid response to changes in physical activity and diet, however, have been reported. The reduced lipid response to dietary changes [24,25] and the greater reductions in LDL-C and total cholesterol (among women only) [26] in AA compared to EA suggests that physiological factors, instead of dietary intake or physical activity, are more informative for interethnic differences in serum lipids.

Physiological Factors

Increasing obesity has long been associated with a worsening of the lipid profile. Paradoxically, the generally healthier distribution of serum lipids in AA exists in spite of higher rates of obesity. The relationship between body fatness and serum lipids appears to differ by ethnicity, with weaker, less statistically significant associations observed between body fat and serum lipids in AA [5,6,27]. It may be that the degree of body fatness, in itself, is less relevant for variation in serum lipids, and the site of fat deposition with increasing adiposity, a parameter with great interethnic variation, is more important. As is well-known, particularly among women, EA are prone to greater accumulation of visceral adipose tissue (VAT) than AA [28]. VAT was observed to be more closely associated with TG than total body fat mass. Similarly, among overweight AA children, waist circumference (reflecting VAT), was more closely associated with lipid profile than BMI (reflecting overall adiposity) [29]. Notably, VAT explained 24.2% of the variance in TG, while other statistically significant predictors (lipase activity, ethnicity, gender, and total fat mass) only explained an additional 9.3% of the variance [28]. Although decreased VAT deposition among AA may explain some protection from dyslipidemia with increasing adiposity among AA (especially AA women), interethnic differences in serum lipids are also observed among lean individuals, hence further explanations are needed.

Difference in the activity of lipases is frequently cited as a potential explanation for interethnic lipid variability, with particular attention given to lipoprotein lipase (LPL), the enzyme primarily responsible for the hydrolysis of TG. AA have significantly greater LPL activity than EA [28]. Notably, after controlling for LPL activity, sex, fat mass, VAT, and age, ethnicity was no longer a significant predictor of HDL-C [28]. On its own, LPL activity explained 23.2% of the total 33.5% of the variability attributed to this set of variables, suggesting that interethnic difference in HDL-C may be primarily due to differences in LPL activity. After adjusting for LPL and hepatic lipase activity, sex, fat mass, and VAT, ethnicity remained a significant predictor of TG [28].

In other populations, decreased LPL activity has been observed with insulin resistance (IR), a potential explanation for the dyslipidemia that co-occurs with IR. In AA, however, no change in LPL activity was found with increasing IR, suggesting a potential mechanism through which a healthy lipid profile often persists even in the presence of IR, as is often observed in AA [30].

While higher activity of LPL in AA is a plausible explanation for the observed differences in serum lipids, the reason for the increased LPL activity is unclear. As insulin stimulates LPL, the higher acute insulin response to glucose seen in AA may be another part of this story. When age- and BMI-matched AA and EA women were given a glucose challenge, a nearly 2.5 times higher acute insulin response was observed in AA. The concomitant increased free fatty acid clearance in AAs was no longer significant after adjustment for this extreme rise in insulin [31]. Given the greater comparability of AA and Hispanic Americans (HA) in terms of IR and body composition, a comparison of the response to glucose challenge in AA and HA adolescents is also informative. The acute insulin response to an intravenous glucose challenge was 63% higher in AA compared with HA [32]. Similarly, AA children had more than twice the acute insulin response than EA children, with a subsequently lower free fatty acid nadir. Adjustment for this free fatty acid nadir abolished the interethnic differences in baseline and post-challenge TG [33]. Together, this evidence [31–33] supports the hypothesis that an increased acute insulin response to glucose challenge in AA causes a reduction in free fatty acids, which may contribute to constitutively lower TG concentrations.

Genetic Factors

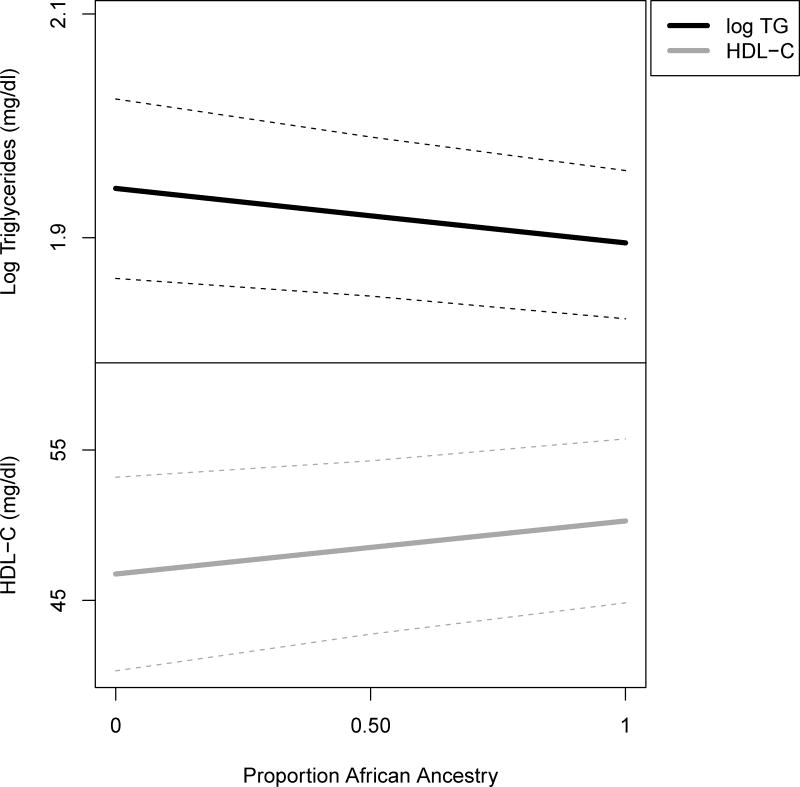

Similarities in the serum lipids of AA with West Africans, despite environmental factors that more closely resemble EA, along with the plausible contribution of physiological differences, suggest the importance of genetic factors in explaining interethnic differences in serum lipids. AA are an admixed population, with chromosomes that are a mosaic of segments that are inherited from two main parental populations, African and European (~20% European ancestry observed, on average, among AA). A relatively straightforward analysis involves estimating the proportion of loci across the genome at which a person has the “African” vs. “European” derived allele. A 10% increase in an individual’s overall African ancestry (a genome-wide average) was associated with a ~1% decrease in serum TG and a 0.7 mg/dl increase in HDL-C, after covariate adjustment (Figure 1), providing strong support for the role of genetic variation in serum lipid interethnic differences. By determining the ancestry at specific loci and evaluating the association between this “local ancestry” and serum lipids (admixture mapping), three genes were identified as potential contributors to the interethnic variation in lipid profile: LPL-HDL-C, GCKR-TG, and ApoB-LDL-C. Further, specific variants in LPL are reasonable candidates for a role in the TG and HDL-C differences [34], consistent with above observations regarding the role of LPL activity.

Figure 1. Association of Serum Lipids with Mean Genome–Wide African Ancestry.

Lower TG and higher HDL-C are associated with increasing African ancestry, calculated as the proportion of genome-wide loci at which an individual has an “African” vs. “European” derived allele. Estimates were obtained through multiple regression models in non-diabetic African Americans from the Howard University Family Study. Models were adjusted for BMI, gender, age, education, alcohol intake, and smoking habits.

Gene sequencing efforts have identified ethnic differences in the association of ANGPTL genes and serum lipids. ANGPTL inhibits LPL, and tissue-specific ANGPTL expression is presumed to regulate partitioning of fatty acids [35]. Loss-of-function variants in ANGPTL3, ANGPTL4, and ANGPTL5 are associated with reduced plasma TG [36]. Interestingly, the distribution of these variants is not uniform across ethnicity for two of these genes. Of the rare variants found in ANGPTL4 in the Dallas Heart Study, 8 of 13 were in EA individuals, and a more common sequence variant associated with TG in EA was in lower frequency in AA and HA. Additionally, the ratio of nonsynonymous to synonymous variants was much higher in EA (4:1) than AA (1.3:1) [36]. In ANGPTL3, however, 10 of 13 of the rare variants identified in individuals with low TG were in AA, and a common variant associated with TG in AA (MAF 10%) was in very low frequency in EA and HA (MAF 0.1%). The authors propose that these interethnic differences in the distribution of rare variants may reflect different historical selection pressures [35]. The differences between these genes in terms of expression patterns, activity, and induction of these ANGPTL isoforms (reviewed in [37]), make this an intriguing target for research into interethnic differences in lipid profiles.

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have provided useful insight into the biology of serum lipids in predominantly European ancestry populations. For example, the meta-analysis of >100,000 European ancestry participants reported genome-wide significance for 95 loci [38]. The authors assessed the generalizability of their findings by attempting replication in AA [38]. Only 30% of the SNPs tested for each trait were successfully generalizable (Table S 12 of that paper), fewer than in the other groups in which replication was sought. From this and other replication efforts in AA, there is now evidence for the transferability of 40 of the 95 loci [39]. Decreased transferability of European ancestry results to AA has also been observed in NHANES data [4,40]. Potential explanations for observed trans-ethnic non-transferability of GWAS loci include differences in sample size, allele frequency, effect size, and gene-by-environment interactions. Some lipids-associated variants with marked differences in allele frequency by ancestry are shown for illustration (Table 2; a more thorough exploration of this topic has been conducted for variants identified by GWAS analyses [41]).

An intriguing possibility that has been proposed is that variants for which positive selection has occurred in Africa as a result of protection from endemic parasitic infections and other environmental factors may have consequences in the distribution of serum lipids as well as other traits that vary between African and non-African ancestry populations. Variants at the APOL1 locus are hypothesized to protect against a deadly form of African Sleeping Sickness [42]. Interestingly, APOL1 is an HDL-associated protein, and preliminary evidence suggests that these variants influence the distribution of HDL particle sizes [43]. Work from our group revealed that one of these variants modifies the association of HDL-C with a measure of kidney function, such that higher HDL-C is associated with worse kidney function in those with the risk genotype, while no association is observed among those without this genotype [44]. A CD36 SNP that has been associated with malaria susceptibility was also associated with increased HDL-C, decreased TG, and increased MetSyn risk among AA. This SNP is absent in the EA and has a MAF of 6% in AA. Fifteen other CD36 SNPs were also associated with HDL metabolism [45]. Variants in PCSK9 have been associated with alterations in lipid metabolism [46] and have been hypothesized to offer a selective advantage in the presence of parasitic infections, as parasites depend on the host’s cholesterol and having decreased cholesterol would lessen the degree of infection [47].

Interethnic differences in response to lipid-lowering medications have been observed, suggesting the role of genetic factors. Trials of common statins have shown reduced LDL-C response in AA vs. EA, resulting in diminished LDL-C control despite high adherence in all subgroups [48,49]. Specific genetic loci with interethnic frequency differences that are associated with variable drug response have been identified. LDLR and HMGCR haplotypes have been associated with attenuated response to simvastatin, with the greatest attenuation observed in those with specific combinations of LDLR and HMGCR haplotypes. The prevalence of each of these haplotypes is much higher in AA than EA (21% vs. 3% for LDLR, 32% vs. 2% for HMGCR, and 14.5% vs. <1% for the combined haplotypes) [50]. An interethnic difference in the pharmacokinetics of pravastatin has been observed, with a significantly lower maximum concentration and area under the curve among AA than EA [51]. These differences may be influencing the results observed in the ALLHAT Lipid-Lowering Trial: AA taking pravastatin experienced a 29% lower risk of heart disease than those receiving usual care, but there was no benefit among those without African ancestry [52]. Clearly further pharmacogenetic studies are warranted to unravel these differences in treatment response and to better target therapies to individual genetic background.

WHY DOES IT MATTER?

While the determinants of interethnic differences in serum lipids are key in disentangling the biological mechanisms that underlie the distribution of these important biomarkers, there is much greater public health significance to these differences than simple description. Notably, there is evidence that the association between serum lipids and disease risk is different for AA, particularly as relates to IR, a key determinant of Type 2 Diabetes (T2D) and other metabolic disorders.

The importance of dyslipidemia in risk of T2D and CVD is underscored in its inclusion as one of the criteria on which a diagnosis of the Metabolic Syndrome (MetSyn) may be based (in addition to measures of obesity, blood pressure, and fasting plasma glucose). The clustering of these metabolic risk factors has been reported to increase the risk of CVD up to two-fold and the risk of T2D five-fold [53]. Thus, identification of individuals with the MetSyn for more aggressive preventative strategies is a major public health concern. AA have an increased risk of CVD mortality than EA [1,2], and approximately twice the prevalence of T2D [3]. Paradoxically, as a result of the generally healthier lipid profile in AA, the prevalence of MetSyn is lower among AA [54], and these differences are evident even in childhood, after adjustment for a variety of environmental factors [17].

The development of IR is the primary component that MetSyn is designed to capture, and the interethnic disparities in MetSyn diagnosis highlight more important interethnic differences in the relationship between lipids and IR (this topic has been reviewed by others: [54–57]). Specifically, the associations observed in individuals of European ancestry between serum lipids and IR have been reported to be absent in those of African Ancestry: insulin sensitivity was correlated with TG and HDL-C in EA, but not AA women [58], and similar results were found in comparisons of Black and White South African women [59].

In the face of these interethnic differences, how can screening for those AA at increased risk of metabolic disorders be improved? It has been suggested that serum lipids are still informative for IR, though ethnicity-specific thresholds for establishing increased risk should be adopted. For instance, in the NHANES data, TG/HDL-C was significantly associated with fasting serum insulin in AA, EA, and MA adults, although the optimal threshold for predicting risk of hyperinsulinemia was lower among AA than EA and MA [60]. Similarly, AA with an “intermediate” TG (110–149 mg/dl) had an equivalent degree of IR as those in the higher TG group (≥150 mg/dl), suggesting that the TG values associated with increased risk in AA are, indeed, lower than has been assumed [61]. It has also been proposed that the components of the MetSyn be differently weighted for AA, as these components are differently associated with disease risk in AA [62]. Perhaps less emphasis should be placed on MetSyn for risk detection in AA, with more attention given to investigating characteristics that best predict metabolic disease in AA, including blood pressure, obesity, and possibly nontraditional CVD risk factors, such as psychosocial stressors, adiponectin levels, and cytokines [62].

Worth mentioning in this discussion of serum lipids and disease is the considerable debate regarding potential interethnic differences in the association between lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] and CVD. While the association between Lp(a) and CVD is well-established in those of European ancestry [63,64], a similar relationship among AA was not found. This absence was particularly intriguing given the well-documented interethnic differences in Lp(a) concentrations, with AA having generally higher values [65]. This apparent lack of concordance, however, may be the result of limited power in previous studies [66]: a recent report on over 13,000 individuals (26% AA) found a consistent association across ethnicity between Lp(a) and CVD risk. A 30% increased CVD risk in those with the highest vs. the lowest Lp(a) quintile (notably, the highest quintile among EA was equivalent to the 50th percentile of AA). Of interest, Lp(a) was positively associated with HDL-C in this study [65], an association which has also been observed in AA children [67].

CONCLUSION

Interethnic differences in serum lipid distribution are apparent, with a healthier serum lipid profile observed among AA compared to other US ethnicities. Given observations among those of African ancestry currently living in vastly different environments, these differences are most likely the result of variability in physiological and genetic factors by ethnic group. While understanding the determinants of serum lipid concentrations in AA is an important research objective, especially in the context of the pharmacological management of dyslipidemia, the different association between serum lipids and metabolic disease provide a research objective with potentially greater public health importance. The evidence suggests that metabolic risk occurs at different levels of serum lipids or even irrespective of serum lipid levels. Methods to screen for increased risk of metabolic disorders using serum lipid threshold values are certain to under-identify AA. The establishment of ethnicity-specific criteria for assessing risk of metabolic disorders is crucial considering the disproportionate burden of these disorders among AA and the significant improvements that are possible with the timely intervention that effective screening can facilitate.

EXPERT COMMENTARY AND FIVE YEAR VIEW

Research directed at understanding the complex interplay between environmental and genetic factors in the relationship between lipids and diseases in African ancestry populations should be encouraged. These research projects should not simply be a “generalizability” assessment of findings in European ancestry populations but a strong attempt to shed light on novel evolutionary processes and pathways that may have contributed to patterns of lipid profiles seen in present day populations of the African Diaspora. In this regard, it will be important to study not just AA but also their ancestral populations in West Africa. This strategy will ensure that research findings will be properly contextualized and gene-by-environment interactions will be adequately addressed. Large, long-term prospective studies are needed to establish the extent to which serum lipids are risk factors for CVD mortality and T2D in African ancestry populations. These studies should include the simultaneous collection of demographic, epidemiologic, clinical, and genomic data, making them especially powerful in the effort to understand the evolutionary and medical implications of observed interethnic differences in the relationship between lipids and metabolic disorders in African ancestry populations with implications for other global populations.

KEY ISSUES.

Interethnic differences exist in the distribution of serum lipids, with African Americans generally having a healthier lipid profile (higher high density lipoprotein cholesterol [HDL-C] and lower triglycerides [TG]) than other US ethnic groups.

It is unlikely that lifestyle factors contribute substantially to the interethnic differences in serum lipids, as the higher rates of smoking and obesity, along with a generally poorer diet quality observed in African Americans would be expected to cause a more atherogenic lipid profile.

The higher acute insulin response to glucose that has been observed in African Americans may stimulate lipoprotein lipase activity, leading to greater TG clearance.

Although many loci influencing serum lipids among those of European ancestry appear to be generalizable to those of African ancestry, evidence of considerable heterogeneity exists. A focus on establishing genetic determinants of serum lipids in those of African ancestry is needed, in addition to the current emphasis on assessing the transferability of previous findings in European ancestry individuals.

Paradoxically, the healthier serum lipid profile in African Americans is not associated with a reduced risk of metabolic disorders, such as Type 2 Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease.

A reliance on serum lipids to characterize metabolic risk through use of Metabolic Syndrome criteria may lead to the under-identification of African Americans at risk for metabolic disorders.

Observed interethnic disparities in dyslipidemia treatment success likely stem from a variety of factors, from differences in healthcare delivery and patient adherence to reduced response to treatment. Pharmacogenetic approaches will be of particular utility in improving drug targeting to increase the treatment effectiveness for African Americans.

Given the disproportionately high rate of metabolic disorders in African Americans, the interethnic differences in the association between serum lipids and disease risk should be a research priority.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Hurley LP, Dickinson LM, Estacio RO, Steiner JF, Havranek EP. Prediction of Cardiovascular Death in Racial/Ethnic Minorities Using Framingham Risk Factors. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. 2010;3(2):181–187. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.831073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gu Q, Burt VL, Paulose-Ram R, Yoon S, Gillum RF. High Blood Pressure and Cardiovascular Disease Mortality Risk Among U.S. Adults: The Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Mortality Follow-up Study. Annals of Epidemiology. 2008;18(4):302–309. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cowie CC, Rust KF, Byrd-Holt DD, et al. Prevalence of Diabetes and Impaired Fasting Glucose in Adults in the U.S. Population. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(6):1263–1268. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang M-H, Ned REM, Hong Y, et al. Racial/Ethnic Variation in the Association of Lipid-Related Genetic Variants With Blood Lipids in the US Adult Population / Clinical Perspective. Circulation: Cardiovascular Genetics. 2011;4(5):523–533. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.111.959577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dai S, Fulton JE, Harrist RB, Grunbaum JA, Steffen LM, Labarthe DR. Blood Lipids in Children: Age-Related Patterns and Association with Body-Fat Indices: Project HeartBeat! American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2009;37(1, Supplement):S56–S64. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lamb MM, Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Lacher DA, Flegal KM. Association of body fat percentage with lipid concentrations in children and adolescents: United States, 1999 – 2004. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2011;94(3):877–883. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.015776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cdc. Prevalence of Abnormal Lipid Levels Among Youths -- United States, 1999–2006. MMWR. 2010;2010(59):29–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.D’adamo E, Northrup V, Weiss R, et al. Ethnic differences in lipoprotein subclasses in obese adolescents: importance of liver and intraabdominal fat accretion. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2010;92(3):500–508. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.29270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giannini C, Santoro N, Caprio S, et al. The Triglyceride-to-HDL Cholesterol Ratio. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(8):1869–1874. doi: 10.2337/dc10-2234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miljkovic-Gacic I, Bunker CH, Ferrell RE, et al. Lipoprotein subclass and particle size differences in Afro-Caribbeans, African Americans, and white Americans: associations with hepatic lipase gene variation. Metabolism. 2006;55(1):96–102. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2005.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson JL, Slentz CA, Duscha BD, et al. Gender and racial differences in lipoprotein subclass distributions: the STRRIDE study. Atherosclerosis. 2004;176(2):371–377. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adeyemo A, Gerry N, Chen G, et al. A genome-wide association study of hypertension and blood pressure in African Americans. PLoS Genet. 2009;5(7):e1000564. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rotimi CN, Dunston GM, Berg K, et al. In search of susceptibility genes for type 2 diabetes in West Africa: the design and results of the first phase of the AADM study. Ann Epidemiol. 2001;11(1):51–58. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00180-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.CDC. National Health and Nutrition Examination Protocol. 2003–2004. National Health and Nutrition Examination Protocol. [Google Scholar]

- 15.CDC. National Health and Nutrition Examination Protocol. 2007–2008. National Health and Nutrition Examination Protocol. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kant AK, Graubard BI. Race-ethnic, family income, and education differentials in nutritional and lipid biomarkers in US children and adolescents: NHANES 2003–2006. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2012 doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.035535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walker SE, Gurka MJ, Oliver MN, Johns DW, Deboer MD. Racial/ethnic discrepancies in the metabolic syndrome begin in childhood and persist after adjustment for environmental factors. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2012;22(2):141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raffensperger S, Kuczmarski M, Hotchkiss L, Cotugna N, Evans M, Zonderman A. Effect of race and predictors of socioeconomic status on diet quality in the HANDLS Study sample. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2010;102(10):923–930. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30711-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deshmukh-Taskar PR, O’neil CE, Nicklas TA, et al. Dietary patterns associated with metabolic syndrome, sociodemographic and lifestyle factors in young adults: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Public Health Nutrition. 2009;12(12):2493–2503. doi: 10.1017/S1368980009991261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clarke PJ, O’malley PM, Johnston LD, Schulenberg JE, Lantz P. Differential Trends in Weight-Related Health Behaviors Among American Young Adults by Gender, Race/Ethnicity, and Socioeconomic Status: 1984–2006. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:1893–1901. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.141317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pan Y, Pratt CA. Metabolic syndrome and its association with diet and physical activity in US adolescents. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108(2):276–286. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.10.049. discussion 286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luke A, Dugas L, Durazo-Arvizu R, Cao G, Cooper R. Assessing Physical Activity and its Relationship to Cardiovascular Risk Factors: NHANES 2003–2006. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):387. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Troiano RP, Berrigan D, Dodd KW, Masse LC, Tillert T, Mcdowell M. Physical Activity in the United States Measured by Accelerometer. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2008;40(1):181–188. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e31815a51b3. doi:110.1249/mss.1240b1013e31815a31851b31813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Furtado JD, Campos H, Sumner AE, Appel LJ, Carey VJ, Sacks FM. Dietary interventions that lower lipoproteins containing apolipoprotein C-III are more effective in whites than in blacks: results of the OmniHeart trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92(4):714–722. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Howard BV, Curb JD, Eaton CB, et al. Low-fat dietary pattern and lipoprotein risk factors: the Women’s Health Initiative Dietary Modification Trial. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2010;91(4):860–874. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Monda KL, Ballantyne CM, North KE. Longitudinal impact of physical activity on lipid profiles in middle-aged adults: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Journal of Lipid Research. 2009;50(8):1685–1691. doi: 10.1194/jlr.P900029-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hosain GMM, Rahman M, Williams KJ, Berenson AB. Racial differences in the association between body fat distribution and lipid profiles among reproductive-age women. Diabetes & Metabolism. 2010;36(4):278–285. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2010.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28**.Despres J-P, Couillard C, Gagnon J, et al. Race, Visceral Adipose Tissue, Plasma Lipids, and Lipoprotein Lipase Activity in Men and Women : The Health, Risk Factors, Exercise Training, and Genetics (HERITAGE) Family Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20(8):1932–1938. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.8.1932. This article provides key evidence on physiological differences between African Americans and European Americans that are relevant to serum lipid distribution, particularly LPL activity and fat distribution. The relative contribution of each of these factors on serum lipid concentrations are evaluated. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raman A, Sharma S, Fitch MD, Fleming SE. Anthropometric correlates of lipoprotein profile and blood pressure in high BMI African American children. Acta Pædiatrica. 2010;99(6):912–919. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2009.01639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sumner AE, Vega GL, Genovese DJ, Finley KB, Bergman RN, Boston RC. Normal triglyceride levels despite insulin resistance in African Americans: role of lipoprotein lipase. Metabolism. 2005;54(7):902–909. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chow CC, Periwal V, Csako G, et al. Higher Acute Insulin Response to Glucose May Determine Greater Free Fatty Acid Clearance in African-American Women. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2011;96(8):2456–2463. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-0532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hasson RE, Adam TC, Davis JN, et al. Ethnic Differences in Insulin Action in Obese African-American and Latino Adolescents. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2010;95(8):4048–4051. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gower BA, Herd SL, Goran MI. Anti-lipolytic Effects of Insulin in African American and White Prepubertal Boys. Obesity. 2001;9(3):224–228. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34*.Deo RC, Reich D, Tandon A, et al. Genetic Differences between the Determinants of Lipid Profile Phenotypes in African and European Americans: The Jackson Heart Study. PLoS Genet. 2009;5(1):e1000342. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000342. This work directly addresses the genetic determinants of the interethnic differences in serum lipid profiles using a variety of methods. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Romeo S, Yin W, Kozlitina J, et al. Rare loss-of-function mutations in ANGPTL family members contribute to plasma triglyceride levels in humans. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2009;119(1):70–79. doi: 10.1172/JCI37118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Romeo S, Pennacchio LA, Fu Y, et al. Population-based resequencing of ANGPTL4 uncovers variations that reduce triglycerides and increase HDL. Nat Genet. 2007;39(4):513–516. doi: 10.1038/ng1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hato T, Tabata M, Oike Y. The role of angiopoietin-like proteins in angiogenesis and metabolism. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2008;18(1):6–14. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38*.Teslovich TM, Musunuru K, Smith AV, et al. Biological, clinical and population relevance of 95 loci for blood lipids. Nature. 2010;466(7307):707–713. doi: 10.1038/nature09270. This article summarizes a meta-analysis of 46 studies of European ancestry cohorts and provides genome-wide data on loci influencing serum lipids. Assessment of the transferability of significant loci to other ethnicities (including African Americans) is conducted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Adeyemo A, Bentley A, Meilleur K, et al. Transferability and Fine Mapping of genome-wide associated loci for lipids in African Americans. BMC Medical Genetics. 2012;13(1):88. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-13-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chang M-H, Yesupriya A, Ned R, Mueller P, Dowling N. Genetic variants associated with fasting blood lipids in the U.S. population: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. BMC Medical Genetics. 2010;11(1):62. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-11-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adeyemo A, Rotimi C. Genetic Variants Associated with Complex Human Diseases Show Wide Variation across Multiple Populations. Public Health Genomics. 2010;13(2):72–79. doi: 10.1159/000218711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Genovese G, Friedman DJ, Ross MD, et al. Association of trypanolytic ApoL1 variants with kidney disease in African Americans. Science. 2010;329(5993):841–845. doi: 10.1126/science.1193032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Freedman BI, Langefeld CD, Murea M, et al. Apolipoprotein L1 nephropathy risk variants associate with HDL subfraction concentration in African Americans. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2011;26(11):3805–3810. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bentley AR, Doumatey AP, Chen G, et al. Variation in APOL1 Contributes to Ancestry-Level Differences in HDL-Kidney Function Association. International Journal of Nephrology. 2012;2012:10. doi: 10.1155/2012/748984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Love-Gregory L, Sherva R, Sun L, et al. Variants in the CD36 gene associate with the metabolic syndrome and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Human Molecular Genetics. 2008;17(11):1695–1704. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cohen JC, Boerwinkle E, Mosley TH, Hobbs HH. Sequence Variations in PCSK9, Low LDL, and Protection against Coronary Heart Disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;354(12):1264–1272. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mbikay M, Mayne J, Seidah NG, Chretien M. Of PCSK9, cholesterol homeostasis and parasitic infections: Possible survival benefits of loss-of-function PCSK9 genetic polymorphisms. Medical Hypotheses. 2007;69(5):1010–1017. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2007.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Simon JA, Lin F, Hulley SB, et al. Phenotypic Predictors of Response to Simvastatin Therapy Among African-Americans and Caucasians: The Cholesterol and Pharmacogenetics (CAP) Study. The American Journal of Cardiology. 2006;97(6):843–850. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.09.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goldberg RB, Guyton JR, Mazzone T, et al. Relationships Between Metabolic Syndrome and Other Baseline Factors and the Efficacy of Ezetimibe/Simvastatin and Atorvastatin in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes and Hypercholesterolemia. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(5):1021–1024. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mangravite LM, Medina MW, Cui J, et al. Combined Influence of LDLR and HMGCR Sequence Variation on Lipid-Lowering Response to Simvastatin. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2010;30(7):1485–1492. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.203273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ho RH, Choi L, Lee W, et al. Effect of drug transporter genotypes on pravastatin disposition in European- and African-American participants. Pharmacogenetics and Genomics. 2007;17(8):647–656. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e3280ef698f. doi:610.1097/FPC.1090b1013e3280ef1698f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Margolis KL, Dunn K, Simpson LM, et al. Coronary heart disease in moderately hypercholesterolemic, hypertensive black and non-black patients randomized to pravastatin versus usual care: The Antihypertensive and Lipid Lowering to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT-LLT) American Heart Journal. 2009;158(6):948–955. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Galassi A, Reynolds K, He J. Metabolic syndrome and risk of cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2006;119(10):812–819. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54*.Sumner AE. Ethnic Differences in Triglyceride Levels and High-Density Lipoprotein Lead to Underdiagnosis of the Metabolic Syndrome in Black Children and Adults. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2009;155(3):S7.e7–S7.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.04.049. A review of the effect of interethnic differences in serum lipids on the identification of African Americans at increased metabolic risk. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gaillard T. Insulin Resistance and Cardiovascular Disease Risk in Black People of the African Diaspora. Current Cardiovascular Risk Reports. 2010;4(3):186–194. [Google Scholar]

- 56*.Dagogo-Jack I, Dagogo-Jack S. Dissociation Between Cardiovascular Risk Markers and Clinical Outcomes in African Americans: Need for Greater Mechanistic Insight. Current Cardiovascular Risk Reports. 2011;5(3):200–206. A review of the different association between serum lipids and risk of disease in African Americans compared to other ethnicities. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Osei K. Metabolic Syndrome in Blacks: Are the Criteria Right? Current Diabetes Reports. 2010;10(3):199–208. doi: 10.1007/s11892-010-0116-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gower B, Ard J, Hunter G, Fernandez J, Ovalle F. Elements of the metabolic syndrome: association with insulin sensitivity and effects of ethnicity. Metabolic syndrome and related disorders. 2007;5(1):77–86. doi: 10.1089/met.2006.0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Goedecke JH, Utzschneider K, Faulenbach MV, et al. Ethnic differences in serum lipoproteins and their determinants in South African women. Metabolism. 2010;59(9):1341–1350. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2009.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Li C, Ford ES, Meng YX, Mokdad AH, Reaven GM. Does the association of the triglyceride to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio with fasting serum insulin differ by race/ethnicity? Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2008;7:4. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-7-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stein E, Kushner H, Gidding S, Falkner B. Plasma lipid concentrations in nondiabetic African American adults: associations with insulin resistance and the metabolic syndrome. Metabolism. 2007;56(7):954–960. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2007.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gaillard T, Schuster D, Osei K. Differential impact of serum glucose, triglycerides, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol on cardiovascular risk factor burden in nondiabetic, obese African American women: implications for the prevalence of metabolic syndrome. Metabolism. 2010;59(8):1115–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2009.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Erqou S, Kaptoge S, Perry PL, et al. Lipoprotein(a) concentration and the risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, and nonvascular mortality. JAMA. 2009;302(4):412–423. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kamstrup PR, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Steffensen R, Nordestgaard BG. Genetically elevated lipoprotein(a) and increased risk of myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2009;301(22):2331–2339. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Virani SS, Brautbar A, Davis BC, et al. Associations Between Lipoprotein(a) Levels and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Black and White Subjects / Clinical Perspective. Circulation. 2012;125(2):241–249. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.045120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ridker PM. Lipoprotein(a), Ethnicity, and Cardiovascular Risk. Circulation. 2012;125(2):207–209. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.077354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sharma S, Merchant J, Fleming SE. Lp(a)-cholesterol is associated with HDL-cholesterol in overweight and obese African American children and is not an independent risk factor for CVD. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2012;11:10. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-11-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]