Abstract

Dating violence (DV) is now recognized as an important public health issue. Prevention and intervention programs are being implemented in school contexts. Such initiatives aim to raise awareness among potential victims and offenders as well as among peer bystanders and offer adequate interventions following disclosure. Yet, a major challenge remains as teenagers may not disclose their victimization or may not feel self-efficient to deal with DV if they witness such violence. As such, teen DV remains largely hidden. A representative sample of 8 194 students (age 14–18) in the province of Quebec, Canada was used to explore teenagers’ self-efficacy to reach out for help or to help others in a situation of DV victimization and perpetration. Analyses are conducted to identify possible correlates of self-efficacy in terms of socio-demographic variable (sex, age) and a history of child sexual abuse and dating victimization. Implications for prevention and support strategies are discussed.

Keywords: self-efficacy, sexual abuse, dating violence, victims

The initiative to edit a special issue on hidden victims is an excellent opportunity to shine a light on teen dating violence (DV). It is a form of violence that is, regrettably, highly prevalent whilst considerably underreported and, until recently, under researched.

Adolescence is considered a crucial period in human development (Connolly et al., 2014). In the context of first romantic relationships, the search for identity and negotiation of the balance between autonomy and intimacy with the partner is a very important challenge for youth. Unfortunately, for a significant number of young people, early romantic relationships are associated with negative experiences that can lead to significant hardship both physically and psychologically. In North America, between 4 and 35% of young people aged 12–21 (girls and boys) have experienced at least one episode of violence in the context of romantic relationships (Foshee and Reyes, 2012, Hamby and Turner, 2013, Haynie et al., 2013). DV is a major public health issue; its long-term effects involve significant costs to health care systems and society (Leen et al., 2013, Offenhauer and Buchalter, 2011).

Although the consequences of DV on the psychological, physical and sexual health of adolescents remain relatively unexplored, available studies underscore some important repercussions. Psychological distress, behavioral problems, suicidal ideation, substance abuse as well as significant impairment in everyday life and in the school context are consequences frequently reported by young people experiencing DV (Banyard and Cross, 2008, Exner-Cortens et al., 2013, Foshee and Reyes, 2012). Such consequences are likely to be particularly severe if teens do not access support services, which is sadly often the case, and DV remains hidden.

A well-known and principal reason for violence to be unseen, is that victims do not always report crime to the authorities (Skogan, 1984). If they do not reach out to formal institutions, offences remain unnoticed. This phenomenon is better known as ‘the dark figure of crime’, as it was coined by Biderman and Reiss (Biderman and Reiss, 1967). In order to get a better idea of the incidence of crimes, we have to turn to other methods of data collection. These include self-report population surveys, more particularly national and international Crime Victim Surveys (CVS; for a discussion of CVS, see Aromaa, 2012, de Castelbajac, 2014, Skogan, 1984). Despite all their shortcomings (e.g. sampling issues, response bias, issues related to recalling incidents and actions), they may give a more accurate picture of crime than institutional data (Wells and Rankin, 1995). For instance, the International Crime Victim Survey reveals that only one third of assaults and 15% of sexual assault are reported to the police (van Dijk et al., 2007). It was long assumed that intra-acquaintance offenses would be more likely to be underreported but this hypothesis does not seem to hold entirely (Skogan, 1977). Different researchers report that they have not found an impact of victim-offender relationship on reporting of crime to the police. It has been suggested that victims who know the offender balance their needs for protection on the one hand and for privacy and fear of retaliation on the other hand in their decision whether or not to report (Felson et al., 2002, Tarling and Morris, 2010). Moreover, victims of domestic violence have been found to use disclosure to the police as a tool for negotiation with the offender and to stop the aggression (Wemmers and Cousineau, 2005). However, following a review of 45 studies into college DV specifically, Sabina and Ho conclude that rates of reporting to police varied from 0% for sexual coercion, date rape, and DV to 12.9% for forced sexual assault (Sabina and Ho, 2014). Meanwhile, it has also been pointed out that even national CVS tend to underestimate domestic violence because of victims’ embarrassment to report the abuse to an interviewer and violent incidents not being labelled as a crime by the victim (Wells and Rankin, 1995). In addition, repeat victimization, which is particularly important in partner violence, is not fully appreciated due to capping of the number of incidents that can be recorded in CVS (Nazaretian and Merolla, 2013).

Regardless of the ambiguity on whether violence committed by an acquaintance is more prone to underreporting or not, it is safe to conclude that many violent crimes are not known to the authorities and that this is potentially problematic (for instance, it affects prosecution and resource allocation, Skogan, 1984). It is, therefore, critical to understand why individuals are unwilling to report violence (Kidd and Chayet, 1984). Multiple reasons have been identified. Victims might avoid going to the police because of previous negative experiences with the police, including unsatisfactory police treatment and performance (Kidd and Chayet, 1984, Ruback et al., 2008, Smith, A., 2001). In addition, victims do not always think an incident is serious enough to report. Fohring (2014) suggests that victims do not always label incidents as a crime or downplay the seriousness of the incident because they want to avoid being labelled as a victim (Fohring, 2014). Other reasons for not reporting are shame and embarrassment (Kidd and Chayet, 1984, Sabina and Ho, 2014, Seimer, 2004). Shame, self-blame and fear of the offender largely explain underreporting of partner violence (Felson et al., 2002). Moreover, Edwards, Dardis and Gidycz (2012) emphasize that minimization of DV is a common reason for nondisclosure, while stress, partner blame and thoughts about ending the dating abuse encourage victims to disclose the violence (Edwards et al., 2012). Sabina and Ho (2014) add that reporting of DV is more likely when the victim acknowledges it as a crime.

More importantly, reluctance to report violence to the police is particularly strong among young people (Edwards et al., 2012, Skogan, 1984, Wells and Rankin, 1995). In her study on help-seeking among a large sample of 14 to 16 year olds, Vynckier (2012) found that only 1 out of 10 respondents who indicated that they had been the victim of theft, extortion or physical violence, reported the incident to the police (Vynckier, 2012). Adolescents seem to be equally unwilling to report DV to the police (Finkelhor et al., 2012, Molidor and Tolman, 1998). It has also been noted that CVS are not adapted to young people and produce underestimations of juvenile victimization (Wells and Rankin, 1995)1.

In addition to not reporting to the police, young people do not tend to reach out to adults when they are experiencing trouble, including teen DV (Ashley and Foshee, 2005, Black et al., 2008, Smith, D. W. et al., 2000). Similarly, it is observed that teenagers lack information on support services and professional resources and they might also distrust professional services, want to keep the abuse a secret, remain autonomous or fear retaliation from the perpetrator if they talk (Crisma et al., 2004, Vynckier, 2012). Apart from this, and not unlike adult victims of intimate partner violence, embarrassment prevents teenagers from disclosing DV (Sears et al., 2006). Another important reason why teenagers do not disclose DV is that they do not necessarily label certain behaviours as improper or unhealthy (Fernet, 2005, Van Camp T et al., 2013) and interpret them as acts of love instead (Hays et al., 2011). Such denial as well as hope that the situation will change does not only prevent them from reporting or reaching out for help, but also from breaking up with the perpetrator (Seimer, 2004), what many teenage DV victims are disinclined to do (Jackson et al., 2000; (Weisz et al., 2007)

If teenagers decide that they need help to deal with violence in their dating experiences, they will turn to their peers rather than adults (Ahrens and Campbell, 2000, Banyard et al., 2010, Black et al., 2008, Kogan, 2004, Weisz et al., 2007). They’d rather talk to their peers than to adults. Moreover, girls are more likely to reach out for help than boys when experiencing DV (Black et al., 2008). Richards and Branch (2011) explored social support from friends and family as a protective factor against experiencing adolescent DV victimization and perpetration (Richards and Branch, 2011). They found that, as opposed to peer support, family support was not significantly related to experiencing DV, but also that the protective role of support from friends only held true for girls. This observation underpins the idea that teenagers, and among them particularly girls, rely on their peers and suggests that a strong social peer network can prevent girls from committing or experiencing DV.

Information regarding help-seeking behavior in case of DV perpetration is sparse. Ashley and Foshee (2005) found that, similar to DV victims, teen DV perpetrators generally choose not to talk and seek help, and female perpetrators are least likely to do so (Ashley and Foshee, 2005). Those that do reach out for help will again look for informal support rather than professional support.

Finally, given the high prevalence of DV, it is likely that teenagers know victims of DV, whom they might reach out to when experiencing DV themselves. Insight into the impact of victimization history on helping and help-seeking behavior is limited and derived from college student samples. Findings are rather inconclusive. Ahrens and Campbell (2000) observed that students with a history of sexual assault victimization tended to be more supportive towards a friend who reveals sexual aggression than respondents without such a victimization history (Ahrens and Campbell, 2000). This observation is opposed by Banyard et al. (2010), who replicated the Ahrens and Campbell study with a larger sample of college students (Banyard et al., 2010). These authors report that the confrontation with sexual assault against a friend causes emotional distress and inhibits helping behavior. This concurs with findings in general victimology research that some victims continue to suffer from trauma and impaired ability to deal with trouble, while other victims succeed in using their past suffering to help others (Van Camp, 2014, Vollhardt, 2009).

The above demonstrates that teen DV is a serious issue that remains largely hidden. Continued research is needed to further unveil this phenomenon and inspire prevention strategies. We might also want to encourage victims and perpetrators to reach out and get help. Furthermore, considering that young people turn to their peers for help when they experience DV, it is imperative to study whether teenagers can deal with such disclosure. An important factor to explore in this respect is teens’ confidence in his or her ability to act. This idea is a key component in Bandura’s writings on human agency and motivation to improve their own or another’s situation. Bandura describes perceived self-efficacy as one’s ‘judgments of how well one can execute courses of action required to deal with prospective situations (Bandura, 1982, p.122)’ or as confidence in one’s capabilities to exercise control (Bandura, 1989). He argues that assessments of self-efficacy impact thought as much as action and, for instance, accounts for coping behavior and self-regulation (Bandura, 1982). The stronger one’s sense of efficacy, the greater the effort to reach a goal and performance achievements, whereas judgments of inefficacy create stress and impair performance (Bandura, 1982, Bandura, 1989). He concludes that ‘among the mechanisms of personal agency, none is more central or pervasive than people’s belief in their capacity to exercise some measure of control over their own functioning and over environmental events. Efficacy beliefs are the foundation of human agency. Unless people believe they can produce desired results and forestall detrimental ones by their actions, they have little incentive to act or to persevere in the face of difficulties (Bandura, 2001, p.10)’. The influence of self-efficacy assessments on behavior has also been included in the theory of planned (or reasoned) behavior, which is an established model regarding the association between attitude and behavior and has been found to successfully predict a variety of behaviors (Ajzen, 2011, Armitage and Conner, 2001). A key premise in this model is ‘that individuals make behavioral decisions based on careful consideration of available information (Connor and Armitage, 1998, p.1430)’. Self-efficacy is one such source of information that people consider when engaging in action.

In light of the above, self-efficacy could also be an important step towards disclosure and outreach in case of DV. For instance, in their review of studies on college DV, Sabina and Ho (2014) clarify that higher levels of self-efficacy increase likelihood of reporting incident to police as well as informal disclosure (Sabina and Ho, 2014).

A pilot study conducted by our research team shows that teenagers feel fairly confident that they can deal with both experienced or witnessed DV, although girls feel more confident than boys. Helping someone else was also reported to be easier than having to reach out for help for oneself. Self-efficacy to deal with DV perpetration was weaker (Van Camp et al., 2014a). Yet, this pilot study had important limitations. It drew on a small sample, which prevented looking into the possible influence of chronicity of victimization experiences. This paper builds on a large, representative sample and, therefore, advances our earlier observations. In this paper we attempt to further unveil the relevance of self-efficacy for help-seeking following experiencing or witnessing DV among youth. More particularly, we ask under which conditions are teens more likely to report DV? In other words, how does perceived self-efficacy relate to gender and past victimization experiences, namely child sexual abuse and dating victimization?

METHODS

Study design and participants

Data collected in the Quebec Youths’ Romantic Relationships Survey (QYRRS) were used for this study. The primary goals of the QYRRS were to identify the prevalence of DV, explore mental health outcomes associated with dating victimization and examine risk factors associated with dating victimization in high school youth. Data were collected through a one-stage stratified cluster sampling of 34 Quebec high schools from third to fifth grade. Considering the education system (private or public), the language of teaching (English or French) and the underprivileged index, eight (8) stratums were created.

Data collected from the QYRRS were imputed and weighted in order to minimize partial non-response and to better represent the population. The sample involved 8 230 teenagers from 329 classes of 34 schools in province of Quebec. After data verification, 36 participants were excluded from the database because of invalid or completely missing responses. The final sample size thus included 8 194 students ranging from 14 to 21 years old. After the application of weight correction factor, the weighted sample was based on 6 540 participants. Among them 2 089 (55.2%) girls and 1 333 (48.4%) of boys reported having a dating relationship in the last 12 months. Socio-demographic characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1. Subsequent analyses are based on these 3 422 participants. All analyses were computed with Stata (StataCorp., 2011).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of study participants (n = 6 540)

| Sample Characteristics | % |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Girls | 57.8 |

| Boys | 42.2 |

| Age groups | |

| 14 years | 23.8 |

| 15–17 years | 74.6 |

| 18–21 years | 1.6 |

| Education | |

| Grade 3 | 37.3 |

| Grade 4 | 31.6 |

| Grade 5 | 31.2 |

| Family structure | |

| Two parents under the same household | 63.1 |

| Shared custody | 12.7 |

| Living with one parent | 21.9 |

| Other family structure | 2.2 |

| Ethnicity of parents | |

| Québécois or Canadian | 70.6 |

| Latino-American or African-American | 4.6 |

| North African or Middle Eastern | 4.6 |

| European | 3.3 |

| Asian | 3.7 |

| Other | 13.2 |

The research ethic boards of the Université du Québec à Montréal approved this project. Participants agreed to participate on a voluntary basis by signing a consent form and questionnaires were administered in class.

Measures

Self-efficacy

The questionnaire included the Self-efficacy to Deal with Violence Scale (Cameron et al., 2007). In this 8-item scale, five items relate to the perception of one’s ability to act when one witnesses or becomes aware of DV against a peer (e.g. ‘How confident are you that you could do something to help a person who is being hit by their boyfriend/girlfriend?’) and three items concern the perception of one’s ability to deal with DV as a victim or perpetrator (e.g. ‘How confident are you that you could tell someone you trust that you are being abused by your boyfriend/girlfriend?’).

Items were scored on a 4-point scale (1= not at all confident; 4= very confident). In a previous study, we validated this questionnaire (Van Camp et al., 2014b). A two-factor structure was identified. The first factor, “Helping behavior as a bystander”, includes five (5) items relate to the perception of one’s ability to act when one witnesses. The second factor, “Help-seeking behavior as a victim or perpetrator” reflects the perception of one’s ability to deal with DV as a victim or perpetrator. We used mean of items included in each factor, then we multiply by 5 so the two scores vary from 5 to 20. In the present study, the two factors showed internal consistency coefficient of 0.80 and 0.51 respectively.

Sexual abuse

Participants were asked to complete items adapted from the Early Trauma Inventory Short Form to assess sexual abuse (Bremner et al., 2007). This questionnaire assessed separately unwanted touching and unwanted sexual intercourse using each one item. Participants endorsing any of these items were then asked to specify the identity of the perpetrator as an immediate or extended family member, a known perpetrator outside the family (excluding a romantic partner) or a stranger. A dichotomized score was created to identify participants reporting having experienced sexual abuse.

Physical, emotional and sexual DV victimization

DV was measured using two questionnaires: the Conflict in Adolescent Dating Relationships Inventory and the Sexual Experiences Survey. The first questionnaire assessed different forms of violence: emotional DV (3 items), physical DV (3 items) and threatening behavior (2 items) in dating relationship (González et al., 2001, Wekerle et al., 2009, Wolfe et al., 2001). Emotional violence included behaviors such as saying hurtful things, ridiculing the partner or keeping track of where one’s partner was and with whom. Physical violence and threatening comprised acts like kicking, hitting, or slapping, pulling one’s hair, or pushing, shoving, shaking, pinning you down or threatening to hurt the other or hit you and throw things at you. The respondents indicated how often the related act has happened to them in the last 12 months on a 4-point Likert Scale (ranging from never to 6 times and more). The second questionnaire, the Sexual Experiences Survey, measured the sexual violence using 9 items (Koss and Gidycz, 1985, Koss and Oros, 1982, Poitras and Lavoie, 1995). This survey assessed 3 main behaviors: unwanted touching, unwanted sexual activity and unwanted sexual activity involving penetration perpetrated by a romantic partner in the past 12 months. For each behavior, the questionnaire included different degrees of coercion. Participants were asked to indicate whether their partner has had the related behavior by using arguments or physical force or by giving them drugs or alcohol. A dichotomized DV victimization score was created according to whether participants reported at least one episode of each form of DV or not.

Sociodemographic information

Information regarding sex, age, family structure (living with two parents under the same household, living with two parents in different households (shared custody), living with one parent, other family structure arrangements), language mostly spoken at home (French, English or other) and ethnicity of parents was collected.

RESULTS

Descriptive scores of used instruments (two factors of self-efficacy) are reported for the entire sample and then separately for boys and girls. Statistical analyses exploring the possible sex difference in the two factors of self-efficacy are presented in the following section. Multivariate regressions were performed to explore possible predictors of self-efficacy and measure their magnitude controlling for age of participants. Predictors include sexual abuse, DV victimization and sex. We also tested interactions among the predictors but none of the interactions reached significance level.

Table 2 summarized descriptive scores of used instruments. Participants show higher score for Helping behavior as a bystander (16.4 for girls and 15.1 for boys; t (26) = 9.4; p<0.001) than Help-seeking behavior as a victim or perpetrator (14.9 for girls and 14.0 for boys; t (26) = 7.5; p<0.001). A higher prevalence of lifetime sexual abuse was found for girls (15.15%) compared to boys (4.38%). Among youths who stated being in a relationship in the last 12 months, 58.24% reported having experienced at least one episode of DV. Girls (63.12%) were more likely to report being victimized than boys (50.56%).

Table 2.

Means and standard errors of main variables

| Variables | Girls | Boys | Total sample |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-efficacy (M ± SE) | |||

| Witnessing DV | 16.4 ± 0,11 | 15.1 ± 0.14 | 15.8 ± 0.10 |

| Experiencing DV | 14.9 ± 0 .07 | 14.0 ± 0.10 | 14.5 ± 0.06 |

| Sexual abuse (%) | 15.15 | 4.38 | 10.60 |

| Dating Violence (%) | 45.90 | 32.26 | 40.59 |

Results of multivariate regression analyses are presented in Table 3 first for “Bystander” and then for “Victim or perpetrator”. The first factor, Helping behavior as a bystander, was negatively related to a history of sexual abuse (β = −0.34, p = 0.006) and experiences of dating victimization in the past 12 months (β = −0.44, p < 0.001). Thus experiencing sexual abuse as well as sustaining DV in the past 12 months contributes to the prediction of lower self-efficacy scores. Results also show that sex is a significant predictor in that overall, girls are more likely to help than boys (β =1.39, p <0.001). Age of participants was not found to significantly influence self-efficacy.

Table 3.

Multivariate regression to predict perceived self-efficacy when witnessing or experiencing DV

| Perceived self-efficacy when witnessing DV (F(4, 24) = 57.2, p <0.001) | Perceived self-efficacy when experiencing DV (F(4, 24) =21.8, p <0.001) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| β | SE | p | β | SE | p | |

| Sexual abuse | −0.34 | 0.11 | 0.006 | −0.43 | 0.18 | 0.03 |

| Dating violence | −0.44 | 0.09 | <0.001 | −0.56 | 0.12 | <0.001 |

| Sex | 1.39 | 0.13 | <0.001 | 0.88 | 0.14 | <0.001 |

| Age | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.18 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.59 |

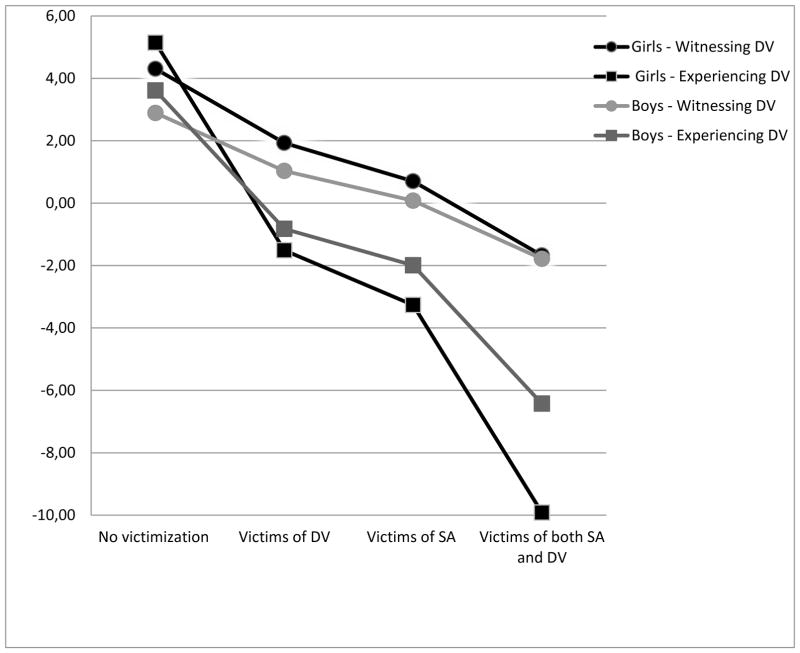

Analysis computed on the second factor, Help-seeking behavior as a victim or perpetrator, revealed that sexual abuse (β = −0.43, p = 0.029), dating victimization (β = −0.56, p <0.001) and sex (β =0.88, p <0.001) were significant predictors. Sexual abuse and dating victimization negatively affected the perception of one’s ability to seek help. Girls were also found to be more likely to seek help if they were victims or perpetrators compared to boys. Figure 1 show the standardized adjusted means of perceived self-efficacy scores when witnessing and experiencing DV by 4 groups (No victimization, Victims of DV, Victims of SA, Victims of both DV and SA). The figure illustrates that non-victimized teenagers have a higher sense of self-efficacy while teenagers reported both a history of sexual abuse and dating victimization report lower self-efficacy.

Figure 1.

Standardized adjusted mean of perceived self-efficacy scores when witnessing and experiencing DV by gender

DISCUSSION

This paper aims to explore self-efficacy among youth regarding help-seeking following experiencing or witnessing DV. Increased insight into teenagers’ willingness to reach out when experiencing or witnessing DV illuminates why teen DV, similarly to other forms of interpersonal violence, remains hidden. In addition, this paper aims to address gender differences among teens as well as past victimization in relation to perceived self-efficacy. Teenagers in general report that they would find it easier to help others who are suffering from DV than to reach out for help for themselves. Many studies have documented the adverse consequences associated with DV, which may act as help-seeking barriers for teens who are experiencing DV. In many cases, victims are not willing to even share their experiences (Foshee, 2005, Vynckier, 2012). As this phenomenon has become a general concern, youth who witness their peers experiencing DV may be more responsive to seek and provide help for them. Hence, awareness programs should be continued and focus more on victimized teens. Those who witness DV as a bystander can be seen in such prevention programs as facilitators to address help-seeking behaviors following DV.

Results from this study also point out the gender difference related to helping and help-seeking behavior. Consistent with past research (Black et al., 2008; Martin, Houston, Mmari, & Decker, 2012), girls are more likely to offer help when witnessing DV than boys. As victimization prevalence in dating relationships reported by girls is generally greater than those reported by boys, it is possible that girls are more sensitive and reactive about DV. Additionally, boys are not only more reluctant to reach out to victims or perpetrators but also to find help when they are experiencing DV. In their qualitative study, Martin and colleagues (2012) found that male participants cited fear of losing pride or their reputation as main reasons for not seeking help, while females were apprehensive of the potential feelings of shame following disclosure to friends and family. Thus, gender-separate intervention programs may be beneficial in addressing differential perceived barriers to disclosure and perceptions regarding help-seeking behaviours (Black et al., 2008). Since boys seem more reticent to seek help than girls, prevention programs should target this specific clientele and tailor their interventions to focus on male socialization and stereotypes, such as obtaining help as a sign of weakness (Black et al. 2008).

The present study also addresses the perceived self-efficacy of teenagers with a history of sexual abuse victimization or DV victimization to seek support in face of DV. The evidence suggests that teenagers with such history perceived themselves as less apt to seek help and help out others who are experiencing or committing DV; this sustains the idea that the most vulnerable population may remain hidden. This is consistent with scholarly reports suggesting that the impacts of sexual abuse, as well as DV, include feelings of shame, powerlessness and decreased sense of self-efficacy to cope with subsequent difficult situations due to the experienced trauma. In other words, as our study documents, adolescents who have experienced multiple acts of victimization are less likely to ask for help for themselves and perceive themselves as less able to help others who are experiencing DV.

Given that adolescent DV victims most often cite friends as the most helpful sources of support (Sylaska & Edwards, 2014), and that increased peer support may lessen post-traumatic stress symptoms (Hébert et al., 2014), peers represent an important avenue for intervention efforts. Therefore, DV prevention programs should also be aimed towards young witnesses of DV. Oftentimes, youth who are confided in don’t have the necessary tools required to provide adequate support, which can sometimes result in blaming the victim, minimizing their experiences or simply not being able to offer any form of help (Martin et al., 2012). Teaching adolescents how to respond to such disclosures in a positive and supportive manner could encourage victims to seek help. Knowing that they can turn to their peers and receive appropriate help can also contribute to reducing the perceived stigma associated with help-seeking initiatives. A safe environment is also essential to encourage DV disclosure. Therefore, schools often represent an ideal environment for education on healthy relationships, establishing DV awareness and offering safe, confidential, non-judgmental sources of formal (school psychologist, social worker) and informal (peers) support.

In order to fully understand help-seeking barriers, it is important to gain further knowledge on youths’ interpretations of DV, their motives for (not) seeking help and the disclosure process as a whole. That being said, very little research exists on the experiences and perspectives of youth who provide support (or not) to their peers following DV disclosure. In their recent review, Sylaska and Edwards (2014) suggest that programs should aim at fostering positive reactions to victims since they are beneficial in reducing negative mental health consequences (e.g., decreased symptoms of depression, anxiety and PTSD).

Our study involves limitations. Given the cross-sectional nature of the data, it is not possible to test the temporal link between victimization experiences and self-efficacy. In addition, the second factor of the self-efficacy measure used presented a low internal consistency score. The few number of items (3) combined with the fact that both disclosure to someone in the situation of victimization and perpetration of DV is included might explain this low reliability. Future studies, perhaps relying on a qualitative approach, may offer additional insights as to youths’ perceived challenges and facilitators to help-seeking.

CONCLUSION

Teen DV is an important public health issue but remains manifestly underreported and was until recently largely under researched. How can we unhide teen DV? By encouraging victims to reach out to someone (peer, adult) and by empowering these witnesses to provide help or refer to support resources. Young people tend to rely on their peers, who then need to be aware of the seriousness of DV and given tools to deal with such disclosure. Our findings suggest that there is a particular need for tailored programs for boys and teens with a history of victimization while consolidating the universal prevention programs involving bystanders.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research awarded to Martine Hébert (CIHR # 103944).

Footnotes

This double dark figure of crime reinforces the value of specific self-report research into teen DV (which has been found to be a reliable method to record youth violence, see for instance (Brener et al., 2002, Denniston et al., 2010, Koss and Gidycz, 1985, Rosenblatt and Furlong, 1997) as well as data triangulation.

References

- Ahrens CE, Campbell R. Assisting Rape Victims as They Recover From Rape The Impact on Friends. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2000;15:959. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behaviour: reactions and reflections. Psychology & Health. 2011;26:1113. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2011.613995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armitage CJ, Conner M. Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analytic review. British journal of social psychology. 2001;40:471. doi: 10.1348/014466601164939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aromaa K. Victimization surveys: What are they good for? Temida. 2012;15:85. [Google Scholar]

- Ashley OS, Foshee VA. Adolescent help-seeking for dating violence: Prevalence, sociodemographic correlates, and sources of help. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2005;36:25. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American psychologist. 1982;37:122. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Human agency in social cognitive theory. American psychologist. 1989;44:1175. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.44.9.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual review of psychology. 2001;52:1. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banyard VL, Cross C. Consequences of teen dating violence understanding intervening variables in ecological context. Violence Against Women. 2008;14:998. doi: 10.1177/1077801208322058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banyard VL, Moynihan MM, Walsh WA, Cohn ES, Ward S. Friends of Survivors The Community Impact of Unwanted Sexual Experiences. Journal of interpersonal violence. 2010;25:242. doi: 10.1177/0886260509334407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biderman AD, Reiss AJ. On exploring the “dark figure” of crime. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 1967;374:1. [Google Scholar]

- Black BM, Tolman RM, Callahan M, Saunders DG, Weisz AN. When will adolescents tell someone about dating violence victimization? Violence against women. 2008;14:741. doi: 10.1177/1077801208320248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner JD, Bolus R, Mayer EA. Psychometric properties of the early trauma inventory–self report. The Journal of nervous and mental disease. 2007;195:211. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000243824.84651.6c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brener ND, Kann L, Mcmanus T, Kinchen SA, Sundberg EC, Ross JG. Reliability of the 1999 youth risk behavior survey questionnaire. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;31:336. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00339-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron CA, Byers ES, Miller SA, Mckay SL, Pierre MS, Glenn S. Dating Violence Prevention in New Brunswick. New Brunswick: Muriel McQueen Fergusson Centre for Family Violence Research; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Connolly J, Heifetz M, Boislard P, MA . Les relations amoureuses. In: CLAES M, editor. Psychologie de l’adolescent: Perspectives Scientifiques Contemporaines. Montréal: Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Connor M, Armitage C. Extending the theory of planned behavior: A review and avenues for further research. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1998;28:1429. [Google Scholar]

- Crisma M, Bascelli E, Paci D, Romito P. Adolescents who experienced sexual abuse: fears, needs and impediments to disclosure. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2004;28:1035. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Castelbajac M. Brooding Over the Dark Figure of Crime The Home Office and the Cambridge Institute of Criminology in the Run-Up to the British Crime Survey. British Journal of Criminology. 2014;54:928. [Google Scholar]

- Denniston MM, Brener ND, Kann L, Eaton DK, Mcmanus T, Kyle TM, Roberts AM, Flint KH, Ross JG. Comparison of paper-and-pencil versus Web administration of the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS): Participation, data quality, and perceived privacy and anonymity. Computers in Human Behavior. 2010;26:1054. doi: 10.1177/0193841X10362491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards KM, Dardis CM, Gidycz CA. Women’s disclosure of dating violence: A mixed methodological study. Feminism & Psychology. 2012;22:507. [Google Scholar]

- Exner-Cortens D, Eckenrode J, Rothman E. Longitudinal associations between teen dating violence victimization and adverse health outcomes. Pediatrics. 2013;131:71. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felson RB, Messner SF, Hoskin AW, Deane G. Reasons for reporting and not reporting domestic violence to the police*. Criminology. 2002;40:617. [Google Scholar]

- Fernet M. Amour, violence et adolescence. PUQ 2005 [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Ormrod R, Turner H, Hamby S. Child and Youth Victimization Known to Police, School, and Medical Authorities. National Survey of Children’s Exposure to Violence. Juvenile Justice Bulletin. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Fohring S. An integrated model of victimization as an explanation of non-involvement with the criminal justice system. International Review of Victimology 2014 [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, Reyes HLM. Encyclopedia of adolescence. New-York, NY: Springer; 2012. Dating abuse: Prevalence, consequences, and predictors. [Google Scholar]

- González LF, Wekerle C, Goldstein AL. Measuring adolescent dating violence: Development of Conflict in Adolescent Dating Relationships Inventory (CADRI) Short Form 2001 [Google Scholar]

- Hamby S, Turner H. Measuring teen dating violence in males and females: Insights from the national survey of children’s exposure to violence. Psychology of Violence. 2013;3:323. [Google Scholar]

- Haynie DL, Farhat T, Brooks-Russell A, Wang J, Barbieri B, Iannotti RJ. Dating violence perpetration and victimization among US adolescents: prevalence, patterns, and associations with health complaints and substance use. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2013;53:194. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays DG, Michel RE, Cole RF, Emelianchik K, Forman J, Lorelle S, Mcbride R, Sikes A. A Phenomenological Investigation of Adolescent Dating Relationships and Dating Violence Counseling Interventions. The Professional Counselor. 2011;1:222. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson SM, Cram F, Seymour FW. Violence and Sexual Coercion in High School Students’ Dating Relationships. Journal of Family Violence. 2000;15:23–36. [Google Scholar]

- Kidd RF, Chayet EF. Why do victims fail to report? The psychology of criminal victimization. Journal of Social Issues. 1984;40:39. [Google Scholar]

- Kogan SM. Disclosing unwanted sexual experiences: Results from a national sample of adolescent women. Child abuse & neglect. 2004;28:147. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Gidycz CA. Sexual experiences survey: reliability and validity. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 1985;53:422. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.3.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Oros CJ. Sexual Experiences Survey: a research instrument investigating sexual aggression and victimization. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 1982;50:455. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.50.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leen E, Sorbring E, Mawer M, Holdsworth E, Helsing B, Bowen E. Prevalence, dynamic risk factors and the efficacy of primary interventions for adolescent dating violence: An international review. Aggression and violent behavior. 2013;18:159. [Google Scholar]

- Molidor C, Tolman RM. Gender and contextual factors in adolescent dating violence. Violence against women. 1998;4:180. doi: 10.1177/1077801298004002004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazaretian Z, Merolla DM. Questioning Canadian criminal incidence rates: a re-analysis of the 2004 Canadian victimization survey. Canadian Journal of Criminology and Criminal Justice/La Revue canadienne de criminologie et de justice pénale. 2013;55:239. [Google Scholar]

- Offenhauer P, Buchalter AR. Teen dating violence: A literature review and annotated bibliography. National Institute of Justice; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Poitras M, Lavoie F. A study of the prevalence of sexual coercion in adolescent heterosexual dating relationships in a Quebec sample. Violence and victims. 1995;10:299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards TN, Branch KA. The relationship between social support and adolescent dating violence: A comparison across genders. Journal of interpersonal violence. 2011:1540. doi: 10.1177/0886260511425796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblatt JA, Furlong MJ. Assessing the reliability and validity of student self-reports of campus violence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1997;26:187. [Google Scholar]

- Ruback BR, Cares AC, Hoskins SN. Crime victims’ perceptions of restitution: The importance of payment and understanding. Violence and victims. 2008;23:697. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.23.6.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabina C, Ho LY. Campus and College Victim Responses to Sexual Assault and Dating Violence Disclosure, Service Utilization, and Service Provision. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2014:201. doi: 10.1177/1524838014521322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sears HA, Byers ES, Whelan JJ, Saint-Pierre M. “If it hurts you, then it is not a joke” Adolescents’ ideas about girls’ and boys’ use and experience of abusive behavior in dating relationships. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2006;21:1191. doi: 10.1177/0886260506290423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seimer BS. Intimate violence in adolescent relationships recognizing and intervening. MCN: The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing. 2004;29:117. doi: 10.1097/00005721-200403000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skogan WG. Dimensions of the dark figure of unreported crime. Crime & Delinquency. 1977;23:41. [Google Scholar]

- Skogan WG. Reporting crimes to the police: The status of world research. Journal of research in crime and delinquency. 1984;21:113. [Google Scholar]

- Smith A. Domestic violence laws: The voices of battered women. Violence and Victims. 2001;16:91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DW, Letourneau EJ, Saunders BE, Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Best CL. Delay in disclosure of childhood rape: Results from a national survey. Child abuse & neglect. 2000;24:273. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00130-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statacorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 12. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tarling R, Morris K. Reporting crime to the police. British journal of criminology. 2010;50:474. [Google Scholar]

- Van Camp T. Victims of Violence and Restorative Justice Practices: Finding a Voice. London, UK: Routledge; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Van Camp T, Hébert M, Fernet M, Blais M, Lavoie F The Paj Research Team. Perceptions des jeunes victimes de violence sexuelle au sein de leurs relations amoureuses sur leur pire expérience. Journal International de Victimologie. 2013:11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Camp T, Hébert M, Guidi E, Lavoie F, Blais M. Teens’ self-efficacy to deal with dating violence as victim, perpetrator or bystander. International Review of Victimology. 2014a:289. doi: 10.1177/0269758014521741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Camp T, Hébert M, Guidi E, Lavoie F, Blais M. Teens’ self-efficacy to deal with dating violence as victim, perpetrator or bystander. International Review of Victimology. 2014b doi: 10.1177/0269758014521741. 0269758014521741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk J, Van Kesteren J, Smit P. Key findings from the 2004–2005 ICVS and EU ICS, WODC. 2007. Criminal victimisation in international perspective. [Google Scholar]

- Vollhardt JR. Altruism born of suffering and prosocial behavior following adverse life events: A review and conceptualization. Social Justice Research. 2009;22:53. [Google Scholar]

- Vynckier G. Mid-adolescent victims:(Un) willing for help? International review of victimology. 2012;18:109. [Google Scholar]

- Weisz AN, Tolman RM, Callahan MR, Saunders DG, Black BM. Informal helpers’ responses when adolescents tell them about dating violence or romantic relationship problems. Journal of Adolescence. 2007;30:853. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wekerle C, Leung E, Wall AM, Macmillan H, Boyle M, Trocme N, Waechter R. The contribution of childhood emotional abuse to teen dating violence among child protective services-involved youth. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2009;33:45. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells LE, Rankin JH. Juvenile victimization: Convergent validation of alternative measurements. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 1995;32:287. [Google Scholar]

- Wemmers JA, Cousineau MM. Victim needs and conjugal violence: Do victims want decision-making power? Conflict Resolution Quarterly. 2005;22:493. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe DA, Scott K, Reitzel-Jaffe D, Wekerle C, Grasley C, Straatman AL. Development and validation of the conflict in adolescent dating relationships inventory. Psychological assessment. 2001;13:277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]