Abstract

Background

Medication nonadherence among Latinos with schizophrenia represents a significant treatment obstacle. Although some studies have examined patient and family perceptions of adherence, few have examined these perceptions together. However, such knowledge can provide a deeper understanding of how family processes may contribute to or impede adherence among underserved groups such as Latinos.

Aims

This study explored perceptions of medication and adherence among Latinos with schizophrenia and key family members.

Method

Purposive sampling was used to collect data from 34 participants: 14 patients with schizophrenia receiving community-based mental health services in an urban public setting and 20 key family members. Informed by grounded theory, semistructured interviews were analyzed by bilingual–bicultural team members.

Results

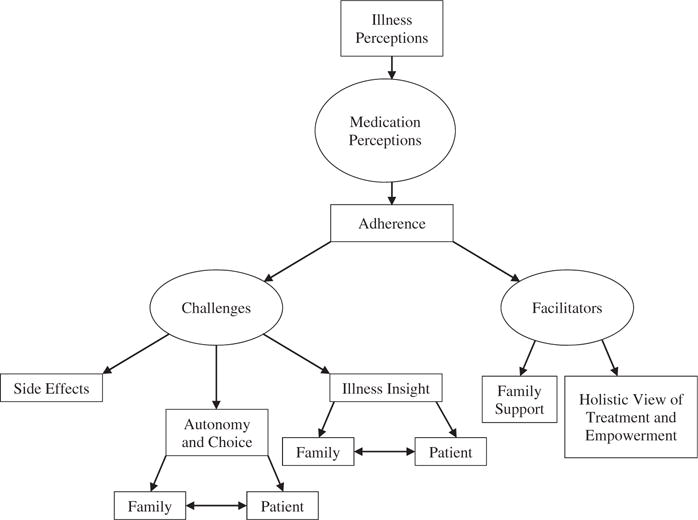

Salient themes emerged indicating facilitators of and obstacles to medication use. Specifically, challenges centered on medication side effects, autonomy and choice, and illness insight, whereas facilitators focused on family support and holistic views of treatment and empowerment.

Conclusions

Because the majority of Spanish-speaking Latinos with schizophrenia live with family, it is important to examine family factors that may influence medication use. Findings suggest that patient and family perceptions of medication should be examined as part of the treatment process, particularly regarding issues of autonomy and choice.

Keywords: Serious mental illness, community mental health, Hispanic, treatment adherence, autonomy and choice

Medication is the first line of treatment for individuals with schizophrenia experiencing active symptoms. Despite advances attributed to atypical antipsychotics, low medication adherence is a substantial problem (Gilmer et al., 2004). An estimated 40% to 50% of the individuals with schizophrenia do not adhere to medication (Lacro et al., 2002). Low adherence is associated with increased clinical symptoms and relapse (Ascher-Svanum et al., 2006; Lanouette et al., 2009; Nosé et al., 2003). Thus, low adherence may lead to a more serious illness course that can complicate recovery for individuals and affect quality of life. In addition, clinical and behavioral manifestations of schizophrenia may have other consequences, such as increased financial costs of the treatment (Desai et al., 2013; Gilmer et al., 2004) and indirect costs related to family well-being (Coker et al., 2016; Hernandez & Barrio, 2015). Factors attributed to nonadherence include medication side effects, substance abuse, poor illness insight, and illness severity (Beck et al., 2011; Gilmer et al., 2004; Lacro et al., 2002; Yang et al., 2012), among others.

Medication adherence is a barrier to adequate care, particularly among racial and ethnic minority groups (Dixon et al., 2011), as evidenced by the growing body of research on disparities in mental health use and services among these groups (Alegría et al., 2007; Barrio et al., 2003; López et al., 2012; Vega et al., 2007). A systematic review of adherence found lower rates among Latinos with serious mental illness compared to European Americans (Lanouette et al., 2009). Another study comparing Spanish-speaking Latinos, English-speaking Latinos, African Americans, and European Americans with serious mental illness found that Spanish-speaking Latinos and African Americans experienced lower levels of adherence than European Americans (Diaz et al., 2005).

Studies have noted the role of perceptions of medication in adherence (Yang et al., 2012), suggesting that understanding views on medication can shed light on beliefs and behaviors that may facilitate or deter medication use among groups such as Latinos (Kopelowicz et al., 2007; Marin & Escobar, 2001). Social context is an important component of adherence, particularly as it relates to family involvement. Families are often highly involved in the pathway to care and provide ongoing care for family members with schizophrenia (Barrio & Dixon, 2012). Moreover, family systems play an important role in transmitting cultural perceptions and practices regarding illness and treatment (Guarnaccia et al., 1992; Hackethal et al., 2013; Jenkins, 1988). For instance, family and cultural perceptions of illness and treatment can influence treatment use including medication (Martinez et al., 2013) due to factors such as stigma (Interian et al., 2007).

Studies have found that individuals who live with or receive support from family members tend to have better medication adherence compared to those who do not (Gilmer et al., 2004; Glick et al., 2011; Kopelowicz et al., 2012; Marquez & Ramírez García, 2011; Ramírez García et al., 2006). Thus, family involvement in medication use may be a protective factor for adherence (Lanouette et al., 2009). Further, these findings point to the importance of families regarding adherence and may be particularly relevant for Latinos with serious mental illness, who are more likely to live with their family than other groups (Barrio et al., 2003; Ramírez García et al., 2009).

However, because most of the studies have examined patient and family member perceptions of medication use and adherence separately, little is known about how the relationship between the patients and family caregivers facilitates or impedes medication use. Therefore, family processes that play a role in adherence may be overlooked. Examining patient and family perceptions can generate greater insight into how to support patients in their treatment and families in their caregiving role. Building on prior research, this study explored perceptions of treatment related to medication use among Latinos with schizophrenia and key family members. In particular, we explored (a) the perspectives of patients and family members regarding medication and (b) how these perspectives contributed to challenges and facilitators of medication use.

Methods

The participants had participated in a controlled study to develop an intervention involving Latino family members caring for a relative with schizophrenia receiving community-based mental health services (Barrio & Yamada, 2010). Data for the current study came from a follow-up study examining perceptions of salient treatment outcomes among intervention group participants. Purposive sampling was used to collect data from 34 participants – 14 dyads (14 patients and 14 key family members), in addition 6 key family members were interviewed although the patient was not available. These six family members were included to provide additional information about family context. Similar to other studies examining Latinos with schizophrenia, all 14 patients lived with their key family member. Table 1 presents additional participant demographic characteristics. The institutional review board of the affiliated university approved all study procedures.

Table 1.

Patient and family member characteristics.

| Patient (N = 14) |

Range | Family (N = 20) |

Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 11 (79) | 4 (20) | ||

| Age, years, M (SD) | 38 (12.00) | 26–75 | 59 (8.48) | 39–72 |

| Education, years, M (SD) | 11.50 (1.65) | 9–14 | 7.30 (4.09) | 2–14 |

| Length of illness, years, M (SD) | 16.38 (11.72) | 7–50 | ||

| Family relation to patient, n (%) | ||||

| Mother | 12 (60) | |||

| Father | 3 (15) | |||

| Spouse | 2 (10) | |||

| Othera | 3 (15) | |||

| Country of birth, n (%) | ||||

| United States | 8 (57) | 1 (5) | ||

| Mexico | 4 (29) | 18 (90) | ||

| El Salvador | 2 (14) | 1 (5) | ||

| Interview language, n (%) | ||||

| English | 8 (57) | 2 (10) | ||

| Spanish | 6 (43) | 18 (90) |

Aunt, daughter, or grandmother.

Semistructured interviews were conducted with participants in their preferred language. The majority (n = 8; 57%) of dyads were interviewed together. The participants were asked about their views on treatment, eliciting responses related to perceptions of medication and issues with adherence. For instance, participants were asked, “What treatment has worked best for you (family member)?” and “What makes treatment difficult for you (family member)?” We used a grounded theory approach (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Strauss & Corbin, 1990) to analyze the data. After independently coding a subset of transcripts, bilingual–bicultural team members discussed emerging findings and reached consensus on codes to develop a codebook. Team members examined co-occurrence of codes and used ongoing comparative analysis to reach a final consensus on themes (Charmaz, 2014). We used Atlas.ti version 7 (Berlin, Germany) to code and organize data.

Results

The data revealed salient themes regarding challenges to and facilitators of medication use that informed a preliminary model (Figure 1) for understanding perceptions of medication among Latino patients and family members. Participants’ illness perceptions often contributed to medication perceptions. Challenges centered on side effects, autonomy and choice, and illness insight. Autonomy and choice and illness insight were often areas of disagreement among patients and family members. Facilitators included family support and holistic views of treatment and empowerment. Other studies on medication adherence noted the themes presented in our model, however, they examined these themes separately among patients and family members and therefore may have missed the family processes that contribute to these perceptions. By including patient and family member perceptions, data can be analyzed to determine congruence and disagreement among participants.

Figure 1.

Preliminary model of patient and family member perceptions of medication adherence among Latinos. Double-sided arrows represent disagreement between the patients and family members.

Medication challenges

Side effects

Patients overwhelmingly described medication side effects as influencing their perceptions of medication adherence. They expressed frustration about taking medications that, although helping reduce troubling symptoms, contributed to other adverse consequences. A patient noted, “It makes me feel a lot better … but, well, medication is medication. … I mean it does the right thing, but …I do get drowsy…”

For some patients, side effects limited their ability to engage in desired activities. One patient said, “I got tired of … the medication and feeling like no interest in nothing, just in my room. Nothing. Even my hobbies; I stopped playing baseball.” He discussed concerns about weight gain that he attributed to the medication: “I was more than obese, so my goal was to get off that medication.”

Although family members recognized the benefits of medication, many expressed concern about long-term use of medication and possible negative effects on patients’ health. For instance, a mother said she was worried “that in the future it can damage organs.” Family members also expressed sadness at seeing their loved ones experiencing side effects, as noted by a mother who said, “It saddens me to see my son like that, sometimes he drools, and he tells me, ‘Do you want to see me like this?”’ Some family members expressed mixed feelings about medication; leading to ongoing assessment of the costs and benefits of medication use.

Balance between autonomy and choice

Autonomy and decision making regarding use of medication was a salient theme among patients. For some patients, views on family involvement in illness management were influenced by perceptions of choice in treatment decisions. Problems arose when patients believed that they did not have a voice in their treatment, resulting in strained family relationships that complicated treatment adherence. For example, a patient described his experience with treatment and medication: “They were forcing it on me… When you get forced…you grow a distance from the person.”

In contrast, another patient shared how he had his treatment needs met by talking to his doctor and reducing his medication:

I had a conversation with my psychiatrist…. My goal was to be off the injections. I just want the oral medication…. So we had a talk and she agreed … but the process took like two years.

Being able to communicate his concern and working with his doctor to reduce his medication gave him a sense of control over his treatment.

Family members’ views on autonomy and choice at times contrasted with patients’ views. They described wanting patients to take an active role in their medication because this decreased family caregiving duties and helped patients be responsible for their own care, leading to increased independence. A mother said, “Now she takes much effort in taking her medicine. Before she didn’t and I took the effort. I would get upset, now she says that she needs to take her medicine.” In addition, several family members said concerns about their loved one’s lack of medication adherence compelled them to administer medication without the patient’s knowledge. Family members who engaged in this behavior felt they had no other alternative because they saw the patient’s symptoms increase due to lack of medication and were concerned about possible relapse. A mother said:

Sometimes I see that he does not take it [medication] and he becomes irritated. Like with a sort of anxiety … and then I begin to give it to him … hidden. And I then see much change in him.

Family members believed they were helping patients by administering medications through food or drink. However, they often struggled and had to persuade patients to consume the food or drink, especially as symptoms increased, creating significant stress for family members and patients.

Illness insight

Given the individual and social impact of schizophrenia, many patients had a difficult time acknowledging their illness. Although most patients recognized that they had a mental illness, those with the greatest adherence challenges seemed to perceive that taking medication indicated that something was wrong, as evidenced by a patient who said, “[I] run, exercise, so that time passes, my mind progresses, and is made stronger to forget my illness. Even though I am taking medicine but say that, I don’t have it.” Despite difficulty accepting his diagnosis, this patient described his need to take medication because he did not want to relapse. “I get sad, how I would like not to have schizophrenia, not take medication, but I say it is better to take it than to be in the hospital.”

Another patient also struggled with accepting his illness and need for medication, creating conflict with his family. “I always think to myself I’m not sick, I’m not sick, I don’t need the medication I tell [family member]. And she goes, ‘You need the medication and this and that.”’ Medication appeared to be tied to perceptions of illness; therefore, patients who struggled with accepting their illness appeared to experience incongruence between their beliefs and behavior.

Moreover, family members’ views regarding medication use differed from patients’ illness insight process. Family members said they believed that illness insight was an important component of medication use. Families whose loved ones were not compliant with medication recognized that patients’ illness perceptions often influenced adherence. For instance, a mother said:

To be 100 percent conscious of his problem because in the past he would doubt that treatment would help … to be able to say, “I have this problem, I have to take medication, so that I could do it all as if I had nothing.”

Although some patients struggled with insight regarding their illness, possibly due to its effect on their identity as individuals, family members viewed insight as connected to treatment adherence. Perhaps family members focused on insight as necessary for adherence due to a belief that medication was important to prevent potential relapse, which could cause serious consequences regarding their loved one’s well-being.

Medication facilitators

Family support

Several patients recognized the important role their family members played in helping them manage their medication and illness. Family members accompanied most patients to their medical appointments. Patients appreciated this support, as indicated by a patient who said he was better able to communicate his needs when accompanied by a family member. He noted, “When I go by myself I don’t like it. It doesn’t feel good. Because I cannot … tell my own way out or like tell them, like, what prescriptions.”

Family members also stated that their involvement made a difference in patient medication adherence. Family members described a strong sense of responsibility for involvement and said they saw family support as a resource for patient well-being. For instance, a mother said:

There has to be two medicines, the doctor’s medicine and the family’s medicine. Do you know what makes up the family’s medicine? For there to be more union with them. Talk to them more … and say, “Just because you are sick, it doesn’t mean that I will throw you out.” On the contrary, have them be closer to us.

Families were usually directly involved in providing medication support by being the first to notice increasing symptoms indicating that patients needed assistance. As such, many families were quick to communicate their concerns regarding patient behavior and symptoms to psychiatrists, particularly when they noticed serious medication side effects. For instance, a mother discussed communicating with her son’s psychiatrist after her son neglected to inform his psychiatrist of side effects:

I told her [doctor], “I don’t know what is happening with [patient].” … She said that perhaps it was a side effect of the medication … because he began to deteriorate … but he did not want to tell the doctor and that is why I had to go and tell her.

However, it is important to note that some families struggled to communicate with psychiatrists because of language issues and had to rely on patients to translate. As stated by another family member, “When we go to the doctor I tell him, ‘Tell him please,’ because he [the doctor] does not speak Spanish. ‘If you don’t feel well or if you think that the medication is not helping you, tell him please.”’ Despite these challenges, family members said they did the best they could to facilitate communication with psychiatrists because they believed it was an important part of treatment.

Holistic view of treatment and empowerment

Patients and family members shared a holistic view of treatment that supported medication adherence. Several patients noted their participation in wellness activities at a mental health center, such as meditation groups, and viewed their involvement in these and other practices as promoting their overall health. For instance, a patient said:

I don’t think it [medication] solves everything; you have to do other things too. I don’t think there’s a magic wand… you don’t pop a pill and it’s over. It doesn’t happen that way…. there are things that through meditation… I could endure more of the symptoms easier.

Meditation helped this patient address areas of his life and symptoms not easily managed through medication alone. Another patient also credited his psychosocial activities as helping him in addition to his medication. He said, “Besides medication, therapy does help… and also being able to provide support like being a volunteer.”

Families’ holistic views included religion and spirituality as important resources that helped with illness management, including medication. As stated by one mother:

One has to go to medicine and then with medicine and asking God for recovery, one achieves it. There comes a balance, but if you are given a medication and you say, “This is no good,” well then you are placing yourself in a negative situation, because you know one’s mentality carries much strength.

This mother indicated that asking for God’s help is important in addition to attitudes toward medication use, which may influence being able to obtain the full benefits of medication. Religion and spirituality appeared to be an important resource for her, along with her positive perceptions of the benefits of medication. Family members’ religious and spiritual beliefs did not appear to dissuade them from medication use, because they acknowledged the benefits of medication.

Discussion

This study sought to elucidate perspectives of medication use by Latinos with schizophrenia and their family members. Nonadherence is among the well-documented disparities in mental health treatment experienced by Latinos (Barrio et al., 2003; López et al., 2012; Vega et al., 2007). Our study adds to the knowledge base by exploring Latino patient and family member perspectives, thus examining their intersection and possible overlap and variations more closely. Because Latinos with schizophrenia are more likely to live with a family member compared to other groups, by including both perspectives, we gained a richer understanding of how the relationship between patients and family members contributes to medication use. Examining adherence within the Latino family context is important given the documented disparities in treatment among Latinos, particularly those of Mexican origin (Alegría et al., 2007). Findings revealed that adherence is a complex process involving individual and family factors that together influence perceptions and behaviors regarding medication.

Participants recognized several challenges related to medication use. Concerns were primarily centered on medication side effects. Patients expressed difficulty with low energy, lack of interest in desired activities, and weight gain, among other concerns. Family members also noticed changes in patients’ affect and behavior. Moreover, families worried about long-term medication use and its effect on patients’ health. Other studies examining family member and patient views on medication use among Latinos cited similar concerns (Marquez & Ramírez García, 2011). Several patients and family members described continually assessing the costs and benefits of taking medication, which often produced internal conflict (Rogers et al., 1998).

Patients’ views of their autonomy and choice regarding treatment also influenced medication use. Some patients expressed difficulty when perceiving medication use as forced. Patients wanted to have a voice in medication use, and those who were able to communicate their concerns to their providers and family members appeared to have a better experience with medication.

Family members also stated that autonomy was important, yet they regarded it as an indication of their loved one’s need for independence. The idea of choice regarding medication use was not prevalent among family members, who despite concerns about side effects, said medication was critical to prevent relapse. Further, family members’ beliefs regarding the importance of medication led some to engage in covert medication administration. Studies have examined covert medication among older adults (Haw & Stubbs, 2010), including by family members of individuals with schizophrenia in countries such as India (Srinivasan & Thara, 2002). However, this phenomenon has not been examined in research in the United States with families of individuals with schizophrenia. Latino family members’ behaviors regarding covert administration of medication suggest possible cultural patterns aligned with interdependent relationships that characterize family centered cultures (Barrio, 2000). Of note are the legal and ethical implications created when patients are not able to consent to treatment and exercise their right to refuse medication (Stroup et al., 2002). It is evident that covert medication merits further research among individuals with schizophrenia in the United States, particularly among groups with a high degree of family involvement.

Illness insight and perceptions of schizophrenia also influenced patients’ use of medication. Individuals who struggled with medication had a difficult time acknowledging their illness. Illness insight has been identified as a contributor to adherence (Beck et al., 2011). Individuals may find that accepting the illness generates negative personal and social consequences they cannot manage. In addition, family members may not have completely understood what insight and awareness may entail for patients, because they were mainly concerned with helping their loved ones prevent relapse.

Despite these challenges, participants recognized the crucial role of family support in the management of the illness. Patients appreciated their family members’ concern for their well-being and perceived their family’s reminders about medication use as an indication of their support. Family members were quick to recognize their loved one’s symptoms and intervene when necessary. This type of tangible support has been found in other studies (Marquez & Ramírez García, 2011; Ramírez García et al., 2006). Some families also communicated their concerns with providers and were able to address troubling side effects. However, not all families had access to patients’ providers due to issues with English language proficiency. Some family members have described an inability to communicate with providers and contribute to the treatment process (Rose et al., 2004), and these challenges may be greater among non-English-speaking families (Polo et al., 2012). Limited communication with providers due to limited English language skills and a lack of familiarity with the mental health system were notable barriers experienced by these Latino families.

Participants overwhelmingly recognized the benefits of a holistic view of treatment that incorporated medication use with other treatment options. Patients perceived their involvement in activities such as meditation as important to their treatment. Family members also said family support and particularly religion and spirituality were key components of overall wellness for patients. Such findings highlight the importance of a comprehensive treatment approach that incorporates patient and family preferences that promotes empowerment. Shared decision-making involves collaboration between patients and providers regarding treatment, including medication (Barrio & Dixon, 2012; Deegan & Drake, 2006; Eliacin et al., 2015). Given the role of family in treatment, incorporating family members into the decision-making process is critical to ensuring that patients’ needs and choices are met. Family psychoeducation has proven effective with Latino patients and family members in addressing medication adherence (Kopelowicz et al., 2012) and can be a resource for transmitting knowledge about shared decision-making to improve family members’ awareness of this important issue. As such, findings from the current study will inform the culturally based family psychoeducation, which is the basis of this study, by highlighting shared-decision making in group sessions.

Several limitations should be considered when examining our results. First, because Latinos are a heterogeneous group, our sample of primarily Mexican origin Latinos may not be representative of all Latinos. Nevertheless, because our sample came from a public community mental health setting, our findings may be relevant to other groups. Second, because our sample did not include other racial or ethnic groups, we were not able to compare our findings with other groups and thereby examine the unique Latino experience. However, given that Latinos are more likely to live with family compared to other groups, the caregiving experience including medication adherence may present with additional responsibilities for Latino families who often provide support with limited resources (Hernandez & Barrio, 2015; Magaña et al., 2007). Third, the majority of our sample consisted of male patients and their mothers; future studies should consider examining perceptions of medication use among female patients and other caregivers. Fourth, all family members had participated in a culturally based family psychoeducation intervention and were knowledgeable about the benefits of medication; therefore, examining perceptions of families who have not received such treatment may add another dimension to our understanding of medication use. Fifth, although all the patients discussed problems with adherence, adherence was not formally assessed. Finally, patients had been living with schizophrenia for several years; therefore, future studies may consider examining perceptions of medication use among patients and family members with recent diagnoses.

Conclusion

Findings from this study further illustrate the importance of family involvement in medication use. In particular, providers should consider that concerns of Latino family members regarding a patient’s stability might prevent them from considering that patient’s choices regarding treatment. As such, medication management and shared decision-making must be openly discussed with Latino families and patients in a culturally congruent manner in conjunction with evidence-based treatment.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the families, providers, and community advisory board members who participated in this study.

Dr. Hernandez received support from the National Institute of Mental Health (R36 MH102077) and Dr. Barrio received support from the National Institute of Mental Health (R34 MH076087).

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors certify their responsibility for the research presented and report no known conflict of interest.

References

- Alegría M, Mulvaney-Day N, Woo W, et al. Correlates of past-year mental health service use among Latinos: Results from the National Latino and Asian American Study. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:76–83. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.087197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ascher-Svanum H, Faries DE, Zhu B, et al. Medication adherence and long-term functional outcomes in the treatment of schizophrenia in usual care. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:453–60. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrio C. The cultural relevance of community support programs. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51:879–84. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.51.7.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrio C, Dixon L. Clinician interactions with patients and families. In: Liberman JA, Murray RM, editors. Comprehensive care of schizophrenia: A textbook of clinical management. New York (NY): Oxford University Press; 2012. pp. 342–356. [Google Scholar]

- Barrio C, Yamada AM. Culturally based intervention development: The case of Latino families dealing with schizophrenia. Res Soc Work Pract. 2010;20:483–92. doi: 10.1177/1049731510361613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrio C, Yamada AM, Hough RL, et al. Ethnic disparities in use of public mental health case management services among patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54:1264–70. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.9.1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck EM, Cavelti M, Kvrgic S, et al. Are we addressing the ‘right stuff’ to enhance adherence in schizophrenia? Understanding the role of insight and attitudes towards medication. Schizophr Res. 2011;132:42–9. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory. 2nd. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Coker F, Williams A, Hayes L, et al. Exploring the needs of diverse consumers experiencing mental illness and their families through family psychoeducation. J Ment Health. 2016;25:197–203. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2015.1057323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deegan PE, Drake RE. Shared decision making and medication management in the recovery process. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57:1636–9. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.11.1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai PR, Lawson KA, Barner JC, Rascati KL. Estimating the direct and indirect costs for community-dwelling patients with schizophrenia. J Pharm Health Serv Res. 2013;4:187–94. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz E, Woods SW, Rosenheck RA. Effects of ethnicity on psychotropic medications adherence. Community Ment Health J. 2005;41:521–37. doi: 10.1007/s10597-005-6359-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon L, Lewis-Fernandez R, Goldman H, et al. Adherence disparities in mental health: Opportunities and challenges. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2011;199:815–20. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31822fed17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliacin J, Salyers MP, Kukla M, Matthias MS. Factors influencing patients’ preferences and perceived involvement in shared decision-making in mental health care. J Ment Health. 2015;24:24–8. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2014.954695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmer TP, Dolder CR, Lacro JP, et al. Adherence to treatment with antipsychotic medication and health care costs among medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:692–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.4.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Piscataway (NJ): Aldine de Gruyter; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Glick ID, Stekoll AH, Hays S. The role of the family and improvement in treatment maintenance, adherence, and outcome for schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31:82–5. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e31820597fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarnaccia PJ, Parra P, Deschamps A, et al. Si Dios quiere: Hispanic families’ experiences of caring for a seriously mentally ill family member. Cult Med Psychiatry. 1992;16:187–215. doi: 10.1007/BF00117018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackethal V, Spiegel S, Lewis-Fernández R, et al. Towards a cultural adaptation of family psychoeducation: Findings from three Latino focus groups. Community Ment Health J. 2013;49:587–98. doi: 10.1007/s10597-012-9559-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haw C, Stubbs J. Covert administration of medication to older adults: A review of the literature and published studies. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2010;17:761–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2010.01613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez M, Barrio C. Perceptions of subjective burden among Latino families caring for a loved one with schizophrenia. Community Ment Health J. 2015;51:939–48. doi: 10.1007/s10597-015-9881-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Interian A, Martinez IE, Guarnaccia PJ, et al. A qualitative analysis of the perception of stigma among Latinos receiving antidepressants. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58:1591–4. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.58.12.1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins JH. Ethnopsychiatric interpretations of schizophrenic illness: The problem of nervios within Mexican-American families. Cult Med Psychiatry. 1988;12:301–29. doi: 10.1007/BF00051972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopelowicz A, Wallace C, Liberman R, et al. The use of the theory of planned behavior to predict medication adherence in schizophrenia. Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses. 2007;1:227–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kopelowicz A, Zarate R, Wallace CJ, et al. The ability of multifamily groups to improve treatment adherence in Mexican Americans with schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:265–73. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacro JP, Dunn LB, Dolder CR, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for medication nonadherence in patients with schizophrenia: A comprehensive review of recent literature. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:892–909. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanouette NM, Folsom DP, Sciolla A, Jeste DV. Psychotropic medication nonadherence among United States Latinos: A comprehensive literature review. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60:157–74. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.60.2.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López SR, Barrio C, Kopelowicz A, Vega WA. From documenting to eliminating disparities in mental health care for Latinos. Am Psychol. 2012;67:511–23. doi: 10.1037/a0029737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magaña SM, Ramirez Garcιa JI, Hernandez MG, Cortez R. Psychological distress among Latino family caregivers of adults with schizophrenia: The roles of burden and stigma. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58:378–84. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.58.3.378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin H, Escobar JI. Special issues in the psychopharmaco-logical management of Hispanic Americans. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2001;35:197–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquez JA, Ramírez García JI. Family caregivers’ monitoring of medication usage: A qualitative study of Mexican-origin families with serious mental illness. Cult Med Psychiatry. 2011;35:63–82. doi: 10.1007/s11013-010-9198-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez I, Interian A, Guarnaccia P. Antidepressant adherence among Latinos: The role of the family. Qual Res Psychol. 2013;10:63–85. [Google Scholar]

- Nosé M, Barbui C, Tansella M. How often do patients with psychosis fail to adhere to treatment programmes? A systematic review. Psychol Med. 2003;7:1149–60. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703008328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polo AJ, Alegría M, Sirkin JT. Increasing the engagement of Latinos in services through community-derived programs: The right question project–mental health. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2012;43:208–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez García JI, Chang CL, Young JS, et al. Family support predicts psychiatric medication usage among Mexican American individuals with schizophrenia. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2006;41:624–31. doi: 10.1007/s00127-006-0069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez García JI, Hernández B, Dorian M. Mexican American caregivers’ coping efficacy. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2009;44:162–70. doi: 10.1007/s00127-008-0420-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers A, Day JC, Williams B, et al. The meaning and management of neuroleptic medication: A study of patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Soc Sci Med. 1998;47:1313–23. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00209-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose LE, Mallinson RK, Walton-Moss B. Barriers to family care in psychiatric settings. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2004;36:39–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2004.04009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan TN, Thara R. At issue: management of medication noncompliance in schizophrenia by families in India. Schizophr Bull. 2002;28:531–5. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss AL, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research. Newbury Park (CA): Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Stroup S, Swartz M, Appelbaum P. Concealed medicines for people with schizophrenia: A U.S. perspective. Schizophr Bull. 2002;28:537–42. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega WA, Karno M, Alegria M, et al. Research issues for improving treatment of U.S. Hispanics with persistent mental disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58:385–94. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.3.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Ko YH, Paik JW, et al. Symptom severity and attitudes toward medication: Impacts on adherence in outpatients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2012;134:226–31. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]