Abstract

INTRODUCTION

TREM2 is a lipid-sensing activating receptor on microglia known to be important for Alzheimer's disease (AD), but whether it plays a beneficial or detrimental role in disease pathogenesis is controversial.

METHODS

We analyzed AD risk of TREM2 variants in the NIMH AD Genetics Initiative Study and AD Sequencing Project. We compared each variant's risk and functional impact by a reporter assay. Finally, we analyzed expression of TREM2 on human monocytes.

RESULTS

We provide more evidence for increased AD risk associated with several TREM2 variants, and show that these variants decreased or markedly increased binding to TREM2 ligands. We identify HDL and LDL as novel TREM2 ligands. We also show that TREM2 expression in human monocytes is minimal compared to monocyte-derived dendritic cells.

DISCUSSION

Our results suggest that TREM2 signaling helps protect against AD but can cause harm in excess, supporting the idea that proper TREM2 function is important to counteract disease progression.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, microglia, TREM2, monocyte, HDL, LDL, lipoprotein

Introduction

1.1

The role of microglia in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease (AD) has been a subject of intense study for many years. In response to β-amyloid (Aβ) accumulation, microglia aggregate and participate in Aβ and tau clearance but also in neuroinflammation that damages neurons (1). As such, it is thought that microglia may have a dual role in AD, becoming dysfunctional over the course of the disease and switching from protective to harmful. Recently, genetic studies have identified several AD-associated polymorphisms in microglia-expressed genes such as TREM2 (2, 3), CD33 (4), and CR1 (5). Among these loci, the greatest risk is associated with the rs75932628T polymorphism in TREM2 encoding the R47H missense mutation. Studies of TREM2 deficiency in various models of neurological disease, such as cuprizone-induced demyelination (6), converge on impaired microgliosis in response to insult, suggesting that TREM2 may be crucial for microglial activation. Indeed, genetic targeting of TREM2 in murine AD models has shown a defective capacity of TREM2-deficient microglia to cluster around Aβ plaques. However, mixed results were reported with regard to plaque burden (7, 8), and therefore, as with microglia in general, it is not settled whether TREM2 plays a beneficial or detrimental role in the context of AD.

To shed light on this question, we sought to establish whether TREM2 polymorphisms that increase AD risk are typically loss-of-function, neutral, or gain-of-function. Although R47H has been shown to have ligand-binding defects (7), other AD-associated TREM2 variants have not been evaluated. To address whether ligand-binding deficiency is a consistent feature of risk alleles, we sought to characterize a large panel of mutants. We selected risk alleles based on whole genome/exome sequencing data and tested their function by ligand binding assays. We find that most AD-associated variants demonstrate decreased signaling in response to a variety of ligands, but surprisingly, some markedly increase signaling. Thus, our results suggest that TREM2 signaling helps protect against AD but can cause harm in excess. Finally, to clarify previous findings regarding the role of TREM2 conducted in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) (9, 10), we perform a thorough characterization of TREM2 expression in these cells and find that CD14+ human monocytes do not express TREM2 on the mRNA or protein level, in contrast to monocyte-derived dendritic cells (moDCs), which highly express TREM2 and are therefore suitable for functional studies. Our results support the idea that proper TREM2 function is important to counteract disease progression.

Results

2.1 Risk analysis of TREM2 variants in NIMH and ADSP genetic data

We set out to select TREM2 variants for which we could make inferences about Alzheimer's risk. We analyzed variants present by whole-genome sequencing in the NIMH AD Genetics Initiative Study, and used data on these variants in the AD Sequencing Project whole exome sequencing (ADSP) for replication (Table 1). Family-based association analysis (FBAT) in the NIMH AD families yielded a p-value of 0.004 for R47H, consistent with our previous report in the same NIMH families (11) and confirmed in ADSP (p<3.45e-12; OR=4.5). Other rare variants in TREM2 were not present in more than ten statistically informative families, thereby preventing the computation of reliable p-values. However, several variants were frequent enough to be suggestive between both datasets. R62H had an odds ratio (OR) of 1.7 in NIMH families, confirmed in ADSP (p=0.006; OR=1.4). The related R62C was found in two affected individuals from one NIMH family and had an OR of 0.58 in ADSP, but numbers were too small to draw conclusions. T96K and L211P, which were almost completely linked in both datasets, had OR around 10 in NIMH families, but this was not supported by the replication sample (p=0.85; OR=1.04; p=0.59; OR=1.13, respectively). On the other hand, D87N had an OR of 0.89 in NIMH families but was significantly associated with risk in ADSP (p=0.017; OR=2.3). The stop gain Q33X was biased toward affected individuals in NIMH families and statistically significant for increased risk in ADSP (p=0.025). Finally, H157Y was found in 5/8 affected individuals, but no unaffected individuals were available for comparison; however, it significantly increased risk in ADSP (p=0.01; OR=4.7). Thus, these data suggest increased AD risk for variants other than the previously implicated R47H, R62H, and L211P.

Table 1.

TREM2 gene variants found in the NIMH family-based WGS data and tested for replication in the ADSP case-control samples.

| dbSNP rs ID | Codon change | #Families | #Aff Carr | Med. AAO | #Unaff Carr | Med. Age | MAF | OR | NIMH (P-val) | ADSP-WES P-val; OR(CI); MAF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs201258314 | R62C | 1 | 2/2 | 78 | 0/0 | -- | 0.00068 | NA | -- | 0.65; 0.58(0.05~6.43); 0.0001 |

| rs104894002 | Q33* | 2 | 4/4 | 71 | 1/3 | 73 | 0.00170 | NA | -- | 0.025; (NA); 0.0001 |

| rs75932628 | R47H | 20 | 35/53 | 72.5 | 2/14 | 72 | 0.01390 | 11.7 | 0.004 | 3.45E-12; 4.5(2.7~7.4); 0.005 |

| rs2234253 | T96K | 9 | 11/16 | 71 | 1/6 | 79 | 0.00475 | 11 | -- | 0.85; 1.04(0.65~1.67); 0.003 |

| rs143332484 | R62H | 11 | 12/23 | 73 | 7/18 | 72 | 0.00746 | 1.7 | -- | 0.006; 1.44(1.1~1.88); 0.01 |

| rs2234255 | H157Y | 4 | 5/8 | 74 | 0/0 | -- | 0.00203 | NA | -- | 0.01; 4.7(1.04~21.33); 0.0006 |

| rs2234256 | L211P | 10 | 12/18 | 71 | 1/6 | 79 | 0.00509 | 10 | -- | 0.59; 1.13(0.71~1.81); 0.003 |

| rs142232675 | D87N | 5 | 4/13 | 76 | 2/6 | 76 | 0.002 | 0.89 | -- | 0.017; 2.3(1.1~5.1); 0.0015 |

#Aff Carr: affected carriers over total affected subjects. Med. AAO: median age of onset in affected carriers. #Unaff Carr: unaffected carriers over total unaffected subjects. Med. Age: median of last known ages of the unaffected carriers. MAF: minor allele frequency. CI: confidence interval.

2.2 Functional characterization of selected TREM2 variants

Next, we attempted to correlate risk to functional alterations. TREM2 binds polyanionic ligands such as phospholipids and via the associated intracellular protein DAP12 leads to downstream protein tyrosine kinase and calcium signaling, among other intracellular events (7). We reasoned that the multitude of different signals generated by TREM2 in response to receptor ligation are all related to the activation state of the receptor, for which downstream calcium signaling would provide a reliable readout. Thus, we looked for altered TREM2 activation using a calcium-driven reporter system. Using retroviral transduction, we stably inserted each TREM2 variant, together with DAP12, into a reporter cell line where calcium signals lead to NFAT nuclear translocation and EGFP synthesis. Each reporter line was sorted directly for the TREM2+ population by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), and these sorted lines were used for all subsequent experiments. We characterized R47H, R62H, R62C, T96K, L211P, H157Y, and D87N mutations from the NIMH families and the previously identified R52H, E151K, R136W, and T66M mutations (12). The common variant of TREM2 (TREM2-CV) and non-transduced reporter cells served as positive and negative controls, respectively. mRNA expression of TREM2 and DAP12 by quantitative RT-PCR was similar between constructs and highly correlated (Supplementary Figure 1A), indicating successful viral transduction. By flow cytometry, surface expression ranged from about 50% to 120% of TREM2-CV (Supplementary Figure 1B). The T66M variant had no detectable surface expression, as previously shown (13), and did not show any activation in our assay (data not shown). It also demonstrated lower RNA expression, likely because the non-transduced population could not be sorted out by FACS. On the other hand, the R52H, R62C, and T96K mutations demonstrated somewhat lower surface expression despite their higher RNA expression, which may reflect a true defect in protein trafficking or simply technical variation. All variants besides T66M demonstrated activation when stimulated with plate-bound anti-TREM2 antibody (Supplementary Figure 1C), suggesting that these variants do not affect the overall folding and conformation of TREM2. Activation in response to direct antibody-mediated cross-linkage correlated roughly with surface expression, as expected.

Using these reporter lines, we analyzed TREM2 activation in response to a variety of known lipid ligands. Each ligand was coated on a 96-well plate at different concentrations, and reporter cells containing each TREM2 variant were subsequently plated in duplicate. After 12 hours, the percentage of GFP+ cells at each concentration was determined by flow cytometry. Then, the baseline activation with no ligand was subtracted from each respective activation curve (Supplementary Figure 1D) and area under the curve (AUC) relative to TREM2-CV was used to compare overall activation. An example of a full activation curve is shown in Supplementary Figure 1E. Because of the correlation between surface expression and activation seen with antibody stimulation, we used the activation/expression ratio to determine functional impact. Figure 1A-C show activation vs. surface expression plots for the purified lipid ligands phosphatidylserine (PS), sulfatide (Sulf), and phosphatidylcholine (PC). As previously shown (7), the R47H polymorphism has a profound negative impact on signaling in response to all tested ligands except PC, which in turn elicited a normal response from all variants. The R62C polymorphism showed a similarly dramatic reduction in activation. The H157Y and R62H variants demonstrated a lesser defect. To the contrary, T96K and D87N had consistently higher activation. R52H, R136W, L211P, and E151K were neutral overall. The percentage deviations of each variant from TREM2-CV across ligands is summarized in Figure 1F. As Q33X leads to truncation of nearly the entire protein, it presumably leads to complete loss of function and thus was not assayed.

Figure 1. Activation vs. surface expression plots of TREM2 variants stimulated with different ligands reveals functional alterations.

(A-E). %GFP+ reporter cells were measured over a range of concentrations, summed to obtain AUC for each variant and subsequently normalized to TREM2-CV AUC. Hypomorphic variants (activation/expression significantly less than TREM2-CV) and hypermorphic variants (activation/expression significantly greater than TREM2-CV) are colored blue and red, respectively. Separate plots are shown for (A) phosphatidylserine, (B) sulfatide, (C) phosphatidylcholine, (D) HDL, and (E) LDL. The mean % difference in activation/expression from TREM2-CV is summarized in (F). Plots show pooled data from 3 independent experiments, with statistical significance p<0.05 calculated by Holm-Sidak's multiple comparisons test.

As lipoproteins contain a variety of phospholipids, we tested whether abundant serum lipoproteins such as high-density lipoprotein (HDL) and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) could activate TREM2 in our reporter system. Indeed, both HDL and LDL activated TREM2 variants in a similar pattern as seen for purified phospholipids (Figure 1D, E). These results extend the range of TREM2 ligands and are consistent with the recent observation that lipoprotein particles containing the apolipoprotein E (ApoE) also bind TREM2 (15, 16), which is notable given the association of ApoE polymorphisms with AD (17).

2.3 Determination of TREM2 expression on human peripheral blood monocytes and monocyte-derived dendritic cells

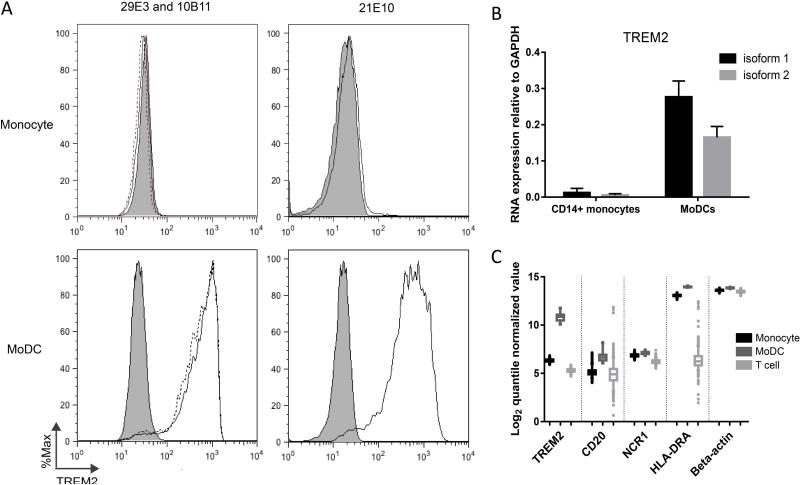

The last part of our study was to determine the utility of PBMCs for TREM2 studies. Early work in healthy donors detected TREM2 only in tissue macrophages and in vitro cultured dendritic cells and macrophages, but not in appreciable quantities in blood monocytes (18, 19). However, recent studies reported increased TREM2 expression on blood monocytes from some AD patients (9) and carriers of a CD33 risk allele for AD (10). We sought to clarify the distribution of TREM2 in blood-derived cell populations at the RNA and protein level. Freshly isolated human PBMCs from normal donors were sorted by magnetic-activated cell sorting into the CD14+ monocyte fraction and CD14− fraction. Flow cytometry was performed using three different monoclonal antibodies against TREM2 as well as CD14 and CD33 to verify the sort purity. While virtually all sorted cells were CD14+CD33+, none of the TREM2 antibodies stained cells to an appreciable degree. The CD14− fraction, as expected, did not contain a TREM2+ population. However, culturing CD14+ cells with IL-4 and GM-CSF for 5 days to produce moDCs led to de novo expression of TREM2 as detected by all three monoclonal antibodies (Figure 2A). To confirm this finding, we performed quantitative RT-PCR on day 0 CD14+ PBMCs and day 5 moDCs (Figure 2B). Consistent with our flow cytometry data, TREM2 transcripts of either isoform 1 or 2 are not present in day 0 human CD14+ monocytes, while they are abundant in moDCs.

Figure 2. TREM2 is expressed by human moDCs but not monocytes.

(A) Representative histograms are shown for staining with three different monoclonal antibodies against TREM2 - 21E10 (right), 29E3 (left), and 10B11 (left) on day 0 CD14+ monocytes or day 5 moDCs. Gray histogram represents isotype control. Similar results were obtained for three donors. (B) RNA was isolated from these same cell populations for quantitative RT-PCR of TREM2 isoforms and GAPDH. Results are averaged from two donors. (C) Analysis of large microarray datasets for human monocytes, moDCs, and T lymphocytes, showing TREM2, CD20, NCR1, HLA-DRA, and beta-actin. 5%-95% intervals are shown, with outliers plotted individually.

For further support, we analyzed microarray data from the ImmVar project, including data on peripheral blood monocytes from 401 healthy subjects, unstimulated moDCs from 30 healthy subjects, and CD4+CD62L+ T lymphocytes from 407 healthy subjects (20, 21) (Figure 2C). We found that the log2 quantile-normalized value for TREM2 transcript in monocytes was consistently low (median 6.33), on par with transcripts specific to natural killer cells (NCR1, median 6.86) and B lymphocytes (CD20, median 5.05), and similar to the level of TREM2 detected in T lymphocytes (median 5.29). In contrast, TREM2 was expressed highly in moDCs (median 10.87). We also checked levels of HLA-DRA and beta-actin as controls. HLA-DRA was expressed highly in monocytes and moDCs but not in T lymphocytes (median 13.07, 13.95, 6.24, respectively) and beta-actin was expressed highly in all three cell types (median 13.60, 13.85, 13.47, respectively), as expected. Together, these results indicate that TREM2, on the mRNA or protein level, is not appreciably expressed in human monocytes but at a high level in moDCs.

Discussion

In our study, we report a novel genetic and functional analysis of several TREM2 variants. Of these variants, some have been previously described to be statistically significant for risk in various populations, others have been reported without adequate sample sizes for accurate assessment of risk, and some have not previously been reported. The functional impact of most of these variants, other than Nasu-Hakola variants and R47H, have not been previously determined. We observed that five variants (R47H, R62H, R62C, H157Y, R52H) had functional features indicating impaired TREM2 function. R47H and R62C showed the greatest defect in activation/expression ratio, while R62H and H157Y showed a more modest defect. R62C and R52H showed diminished surface expression despite higher mRNA expression. This latter observation may reflect a true defect in protein trafficking or alternatively, either technical variation or a deficiency unique to our reporter line rather than human microglia. The R62C and R52H variants have not been identified in large enough numbers thus far to draw conclusions about AD risk, but the other three showed statistically significant risk in our analysis as well as prior reports. The R47H variant significantly increased AD risk in both the NIMH families and ADSP data, and its association with AD has been replicated in a variety of populations. The R62H variant is more common than R47H in the Caucasian population and has previously been shown to confer a statistically significant risk for AD with a smaller effect size than R47H, a conclusion supported by both the NIMH and ADSP datasets. The H157Y variant was previously reported in affected individuals, and it confers a statistically significant increased AD risk in the ADSP dataset. Thus, we have shown that many different AD-associated TREM2 risk alleles impair the ability of the receptor to engage ligand and initiate downstream signaling, supporting an important role for TREM2 and microglial activation in protecting against AD pathogenesis. Finally, the Q33X variant together with other Nasu-Hakola variants that presumably have gross misfolding and loss of function were previously demonstrated to increase AD risk in aggregate, and we confirm statistically significant risk for the Q33X variant alone, as well as lack of cell surface expression of the T66M variant.

On the other hand, 2 variants we tested (T96K, D87N) showed increased activation across all ligands except for phosphatidylcholine. The D87N variant, in particular, showed activation/expression ratio in some cases two or three times as high as TREM2-CV. Despite some conflicting data between datasets, overall both of these activating mutations seem to increase AD risk. While the T96K and highly linked L211P mutations were not associated with increased risk in the ADSP data, their OR in the NIMH data was around 10. In addition, the L211P variant was previously found to be significant for risk in African Americans (14). While in that study, the T96 position was not genotyped, it is likely that the observed risk for L211P would extend to T96K due to their linkage disequilibrium. The D87N variant was previously found to be statistically significant for AD risk (2), and we report a similar finding in the ADSP dataset, although this risk is not observed in the NIMH family data. This finding suggests that overactive TREM2 signaling may also promote the development of AD.

It remains to be assessed whether differences in ligand binding and signaling we report in this study directly correspond to microglial activation or function in vivo. It is unknown which TREM2 ligand or ligands are the most important during the course of AD, and it could be the case that the physiological ligand does not show the same pattern of deficient binding among TREM2 variants. Another possibility is that different levels of TREM2 activation may differentially trigger downstream signaling events in vivo. For example, gross overactivation as seen with T96K and D87N may end up recruiting more phosphatases and leading to decreased microglial activation, cause TREM2 downregulation, or interfere with other microglial signaling pathways. It should be noted that the L211P variant creates a P-X-X-P motif which may bind SH3 domains on various proteins; rather than AD risk being mediated by the linked T96K polymorphism, it could be that risk is being driven by alterations in the signaling apparatus that cannot be detected by our reporter assay. On the other hand, the D87N variant, which does not have this complicating feature, also shows increased risk. Further studies in vivo are required to adequately address the effect of increasing or decreasing TREM2 activation, but our data provide evidence that changes in the upstream binding event are significant in the context of AD pathogenesis.

Notably, we observed that phosphatidylcholine led to a relatively preserved activation/expression ratio for variants that significantly enhanced or inhibited responses to other ligands. This discrepancy suggests that there may be multiple binding modes for TREM2 ligands that could be important in different situations. Additionally, we find that both HDL and LDL can activate TREM2 in our reporter system, which extends the range of TREM2 ligands and is consistent with the recent observation that lipoprotein particles containing apolipoprotein E (ApoE) also bind TREM2 (15, 16). Polymorphisms in apolipoprotein E, which greatly modulate AD risk (17), have not been shown to alter TREM2 binding, but the importance of ApoE-TREM2 interaction in AD pathogenesis is yet to be determined. Activation of TREM2 by HDL or LDL may also be important in the periphery, where many tissue macrophage lineages, including arterial wall macrophages, express TREM2.

We demonstrate that peripheral blood monocytes do not express TREM2 at a comparable level to cell types, such as moDCs, where TREM2 is known to have functional effects. Previous studies that have reported differences in monocyte TREM2 mRNA expression (9) or surface expression (10) between different groups of subjects show increases on the order of 15% or 40%, respectively. In contrast, our data indicate that the increase in TREM2 expression upon differentiation of monocytes into moDCs is on the order of a hundred to a thousand fold. Thus, absolute levels of TREM2 expression in monocytes are quite low and unlikely to be useful for drawing mechanistic conclusions about TREM2. We believe that future studies of this sort should focus on moDCs rather than monocytes. It is possible that monocyte TREM2 expression may be modulated by some AD-associated systemic signal and thus useful as a biomarker, but this remains to be convincingly demonstrated.

Our work provides a link between AD risk and TREM2 function and provides a useful guide for future human TREM2 studies.

Methods

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

Diagnosis of AD dementia was established according to NINCDA-ADRDA criteria. Informed consent was provided by all participants, and research approval was established by the relevant institutional review boards in the study cohort.

Family-based Association Testing

Association analyses of the TREM2 variants in the NIMH-WGS dataset were performed using the family-based association test (FBAT as implemented in PBAT v3.6). See supplementary methods for more detail.

Logistical Regression in Case-Control Whole-exome dataset

Logistical Regression using the binary affection status was performed using PLINK v1.90. See supplementary methods for more detail.

Reporter assay

Phosphatidylcholine (Avanti, #840051P), phosphatidylserine (Avanti, #840032P), and sulfatides (Avanti, #131305P) were reconstituted in methanol, methanol, and chloroform:methanol:water 2:1:0.1, respectively. For each experiment, two Nunc-Immuno MicroWell 96 well solid plates (Sigma) were coated with the purified lipid ligands phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylserine, or sulfatide by diluting to the indicated concentration in methanol and adding 50μL of the resulting solution to each well, with each condition performed in duplicate. Plates were allowed to dry by evaporation, leaving the ligands coated on the well bottom. For human HDL (Millipore) and human LDL (Millipore), stock solution was diluted to the proper concentration in carbonate buffer (15mM Na2CO3, 35mM NaHCO3, pH 9.6) and 50μL of the resulting solution was added to each well, with each condition performed in duplicate. The plates were transferred to 4°C overnight. The next day, solution was aspirated from each well, and each well was washed once with 150μL of PBS. For plate-bound antibody, goat (Fab’)2 anti-mouse IgG (Southern Biotech, cat no. 1012-01) was diluted 1:100 in carbonate buffer, and 50μL of the resulting solution was added to wells in triplicate. The plate was placed at 4°C for 12 hours. Then, solution was aspirated and each well was washed once with 150μL of PBS. 29E3 hybridoma supernatant was plated in each well at 4°C. After 12 hours, the supernatant was aspirated and wells were washed once with 150μL of PBS.

After preparation of the plate, 50,000 cells in 75μL of complete media were added to each well. After 12 hours, the cells were transferred to FACS tube and read on a FACSCalibur. Cells were gated based on forward and side scatter and propidium iodide negativity. The nontransduced control was used to draw the gate for GFP positivity, and this gate was used to determine the %GFP+ for each variant and ligand concentration. The average %GFP+ at the lowest two concentrations for each variant were assumed to be baseline activation, and this value was subtracted from the curve for each respective variant. The values for all concentrations were summed to approximate the area under the curve, which was used for analysis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Y.W. was supported by the Lilly Innovation Fellowship Award (Eli Lilly and Company). This work was funded by grants from NIH 5T32CA009547-30 (T.K.U.), NIMH 5R01MH060009-14, the JPB Foundation (R.T.), RG4687A1/1 from National Multiple Sclerosis Society (M.Ce.), NIH RF1 AG05148501, and the Cure Alzheimer's Fund (M. Co., R. T.).

Footnotes

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists

Authors’ contributions

MCo and RT designed the study. WS, SCJ, and YW conducted experiments. TKU and MCe provided discussion. BH and KM analyzed genetic data. WS, BH, and MCo wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Heneka MT, Golenbock DT, Latz E. Innate immunity in Alzheimer's disease. Nat Immunol. 2015;16:229–236. doi: 10.1038/ni.3102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guerreiro R, Wojtas A, Bras J, Carrasquillo M, Rogaeva E, Majounie E, Cruchaga C, Sassi C, Kauwe JS, Younkin S, et al. TREM2 variants in Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:117–127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jonsson T, Stefansson H, Steinberg S, Jonsdottir I, Jonsson PV, Snaedal J, Bjornsson S, Huttenlocher J, Levey AI, Lah JJ, et al. Variant of TREM2 associated with the risk of Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:107–116. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bertram L, Lange C, Mullin K, Parkinson M, Hsiao M, Hogan MF, Schjeide BM, Hooli B, Divito J, Ionita I, et al. Genome-wide association analysis reveals putative Alzheimer's disease susceptibility loci in addition to APOE. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;83:623–632. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lambert JC, Heath S, Even G, Campion D, Sleegers K, Hiltunen M, Combarros O, Zelenika D, Bullido MJ, Tavernier B, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies variants at CLU and CR1 associated with Alzheimer's disease. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1094–1099. doi: 10.1038/ng.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poliani PL, Wang Y, Fontana E, Robinette ML, Yamanishi Y, Gilfillan S, Colonna M. TREM2 sustains microglial expansion during aging and response to demyelination. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2015;125:2161–2170. doi: 10.1172/JCI77983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Y, Cella M, Mallinson K, Ulrich JD, Young KL, Robinette ML, Gilfillan S, Krishnan GM, Sudhakar S, Zinselmeyer BH, et al. TREM2 lipid sensing sustains the microglial response in an Alzheimer's disease model. Cell. 2015;160:1061–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.01.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jay TR, Miller CM, Cheng PJ, Graham LC, Bemiller S, Broihier ML, Xu G, Margevicius D, Karlo JC, Sousa GL, et al. TREM2 deficiency eliminates TREM2+ inflammatory macrophages and ameliorates pathology in Alzheimer's disease mouse models. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2015;212:287–295. doi: 10.1084/jem.20142322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu N, Tan MS, Yu JT, Sun L, Tan L, Wang YL, Jiang T, Tan L. Increased expression of TREM2 in peripheral blood of Alzheimer's disease patients. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;38:497–501. doi: 10.3233/JAD-130854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan G, White CC, Winn PA, Cimpean M, Replogle JM, Glick LR, Cuerdon NE, Ryan KJ, Johnson KA, Schneider JA, et al. CD33 modulates TREM2: convergence of Alzheimer loci. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:1556–1558. doi: 10.1038/nn.4126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hooli BV, Parrado AR, Mullin K, Yip WK, Liu T, Roehr JT, Qiao D, Jessen F, Peters O, Becker T, et al. The rare TREM2 R47H variant exerts only a modest effect on Alzheimer disease risk. Neurology. 2014;83:1353–1358. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jin SC, Benitez BA, Karch CM, Cooper B, Skorupa T, Carrell D, Norton JB, Hsu S, Harari O, Cai Y, et al. Coding variants in TREM2 increase risk for Alzheimer's disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:5838–5846. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kleinberger G, Yamanishi Y, Suarez-Calvet M, Czirr E, Lohmann E, Cuyvers E, Struyfs H, Pettkus N, Wenninger-Weinzierl A, Mazaheri F, et al. TREM2 mutations implicated in neurodegeneration impair cell surface transport and phagocytosis. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:243ra286. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3009093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jin SC, Carrasquillo MM, Benitez BA, Skorupa T, Carrell D, Patel D, Lincoln S, Krishnan S, Kachadoorian M, Reitz C, et al. TREM2 is associated with increased risk for Alzheimer's disease in African Americans. Mol. Neurodegener. 2015;10:19. doi: 10.1186/s13024-015-0016-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bailey CC, DeVaux LB, Farzan M. The Triggering Receptor Expressed on Myeloid Cells 2 Binds Apolipoprotein E. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:26033–26042. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.677286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Atagi Y, Liu CC, Painter MM, Chen XF, Verbeeck C, Zheng H, Li X, Rademakers R, Kang SS, Xu H, et al. Apolipoprotein E Is a Ligand for Triggering Receptor Expressed on Myeloid Cells 2 (TREM2). J Biol Chem. 2015;290:26043–26050. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.679043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strittmatter WJ, Saunders AM, Schmechel D, Pericak-Vance M, Enghild J, Salvesen GS, Roses AD. Apolipoprotein E: high-avidity binding to beta-amyloid and increased frequency of type 4 allele in late-onset familial Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:1977–1981. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.5.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cella M, Buonsanti C, Strader C, Kondo T, Salmaggi A, Colonna M. Impaired differentiation of osteoclasts in TREM-2-deficient individuals. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2003;198:645–651. doi: 10.1084/jem.20022220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bouchon A, Hernandez-Munain C, Cella M, Colonna M. A DAP12-mediated pathway regulates expression of CC chemokine receptor 7 and maturation of human dendritic cells. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2001;194:1111–1122. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.8.1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raj T, Rothamel K, Mostafavi S, Ye C, Lee MN, Replogle JM, Feng T, Lee M, Asinovski N, Frohlich I, et al. Polarization of the effects of autoimmune and neurodegenerative risk alleles in leukocytes. Science. 2014;344:519–523. doi: 10.1126/science.1249547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee MN, Ye C, Villani AC, Raj T, Li W, Eisenhaure TM, Imboywa SH, Chipendo PI, Ran FA, Slowikowski K, et al. Common genetic variants modulate pathogen-sensing responses in human dendritic cells. Science. 2014;343:1246980. doi: 10.1126/science.1246980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.