Abstract

Objective

This study assessed the effects of 32 mg naltrexone sustained release (SR)/360 mg bupropion SR (NB) on body weight in adults with obesity, with comprehensive lifestyle intervention (CLI), for 78 weeks.

Methods

In this phase 3b, randomized, open‐label, controlled study, subjects received NB + CLI or usual care (standard diet/exercise advice) for 26 weeks. NB subjects not achieving 5% weight loss at week 16 were discontinued, as indicated by product labeling. After week 26, usual care subjects began NB + CLI. Assessments continued through week 78. The primary end point was percent change in weight from baseline to week 26 in the per protocol population. Other end points included percentage of subjects achieving ≥5%, ≥10%, and ≥15% weight loss, percent change in weight at week 78, and adverse events (AEs) necessitating study medication discontinuation.

Results

NB + CLI subjects lost significantly more weight than usual care subjects at week 26 (8.52% difference; P < 0.0001). Weight loss persisted through 78 weeks. In total, 20.7% of subjects discontinued medication for AEs, including 7.0% for nausea.

Conclusions

Treatment with NB, used as indicated by prescribing information and with CLI, significantly improved weight loss over usual care alone. NB‐facilitated weight loss was sustained for 78 weeks and was deemed safe and well tolerated.

Introduction

Obesity is a public health epidemic affecting more than one third of adults in the United States (U.S.); over two thirds of U.S. and half of European adults are overweight or at risk of developing obesity 1, 2, 3, 4. Obesity‐related complications such as type 2 diabetes, heart disease, stroke, and certain cancers are associated with decreased life expectancy and costs totaling up to $147 billion annually in the U.S. 5, 6, 7. Despite these health and economic consequences, many individuals are unable to combat obesity through diet and exercise alone, and few effective drugs are available to assist weight loss 5, 8.

Appetite and eating behavior are controlled by several neural pathways in the brain 9. One key pathway involves pro‐opiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons in the hypothalamus; activation of these neurons is thought to reduce hunger and therefore food intake. Bupropion has been demonstrated to increase POMC activation 10, 11, 12, 13, while naltrexone lessens auto‐inhibition of the POMC pathway by endogenous opioids, leading to a synergistic activation 14, 15, 16. Furthermore, both bupropion and naltrexone are thought to influence the mesolimbic dopaminergic reward pathway, which normally contributes to the reinforcement of behaviors, including feeding 9, 17; the combination of naltrexone and bupropion (NB) may therefore also reduce reward‐driven food intake.

Combination NB sustained release (SR), referred to as extended release (ER) in the U.S. and South Korea and prolonged release (PR) in Europe, has been evaluated for weight loss in four pivotal, placebo‐controlled, double‐blind, randomized phase 3 clinical trials 18, 19, 20, 21. In each of these studies, NB was well tolerated and associated with significant weight loss (approximately 4%‐5% greater mean weight loss compared with subjects receiving placebo and participating in the same lifestyle modification programs) and improvements in various secondary measures of cardiovascular risk. NB therapy was approved for the chronic treatment of obesity by the Food and Drug Administration in the U.S. in 2014 (Contrave®), by the European Medicines Agency in the European Union in 2015 (Mysimba™), and by the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety in South Korea in 2016 (Contrave) as an adjunct to lifestyle modification. Product labeling states that patients are to be evaluated after 16 weeks of treatment to determine whether they have lost at least 5% of initial body weight, and, if not, medication use should be discontinued. The present effectiveness study was designed to determine weight loss achieved when NB is used in a manner consistent with labeling in a real‐world setting, including the use of a commercially available comprehensive lifestyle intervention (CLI) program. As the weight loss efficacy of NB compared with placebo in addition to lifestyle intervention programs of differing intensities was already demonstrated 19, 21, in the current open‐label study the NB + CLI regimen was compared with general advice that patients might receive from their physician (usual care). While this design does not allow for individual assessment of the contribution of NB and CLI to weight loss, it does reflect the overall outcome that would be expected to occur when NB is prescribed according to product labeling and allows for comparison of those outcomes with what might be expected if a physician provides more general weight loss advice and support. Finally, this study examined the effects of NB for up to 78 weeks, longer than the previous phase 3 trials.

Methods

Study design

This was a phase 3b, multicenter, randomized, open‐label, controlled trial designed to assess the effects of 32 mg naltrexone SR/360 mg bupropion SR (NB) in conjunction with a CLI program, compared with usual care (diet and exercise education and recommendations from the study site) on body weight for 26 weeks in subjects with obesity or overweight and dyslipidemia and/or controlled hypertension. Following the first 26 weeks, subjects in the usual care group received NB + CLI in a manner consistent with that of the subjects originally randomized to that treatment group. The study had a total treatment duration of up to 78 weeks. Ethical approval was provided by Schulman Associates IRB, Cincinnati, OH.

Subjects and eligibility criteria

Adult male and female subjects, aged 18 to 60 years, had either obesity (body mass index [BMI] 30‐45 kg/m2) or overweight (BMI 27‐45 kg/m2) with dyslipidemia and/or controlled hypertension. Key exclusion criteria included: type 1 or 2 diabetes mellitus; myocardial infarction within 6 months before screening; angina pectoris grade III/IV (per the Canadian Cardiovascular Society grading scheme); clinical history of large vessel cortical strokes, including ischemic or hemorrhagic strokes (i.e., transient ischemic attack was not exclusionary); history (within 20 years before screening) of seizures, cranial trauma, bulimia, anorexia nervosa, or other conditions that predispose subjects to seizures; chronic use or positive screen for opioids; psychiatric conditions including mania, psychosis, acute depressive illness, or suicide risk; regular use of tobacco products.

Lifestyle intervention programs

CLI was a telephone‐ and Internet‐based program that included a progressive nutrition and exercise program with individualized goal setting and tracking tools. Subjects were to receive up to 11 structured telephone calls from a coach/dietician during the first 26 weeks (controlled treatment period), with up to 12 additional calls offered over the remainder of the 78 weeks (uncontrolled treatment period). Usual care was a site‐based lifestyle intervention program intended to mimic the weight loss support that might typically be provided to patients in a primary care setting. Usual care subjects were instructed at baseline and at week 10 to follow an exercise prescription and a hypocaloric diet, with a target daily caloric intake deficit of 500 kcal, and were given support tools such as a nutrition tracker, pedometer, and healthy weight literature.

Controlled treatment period (week 1‐week 26)

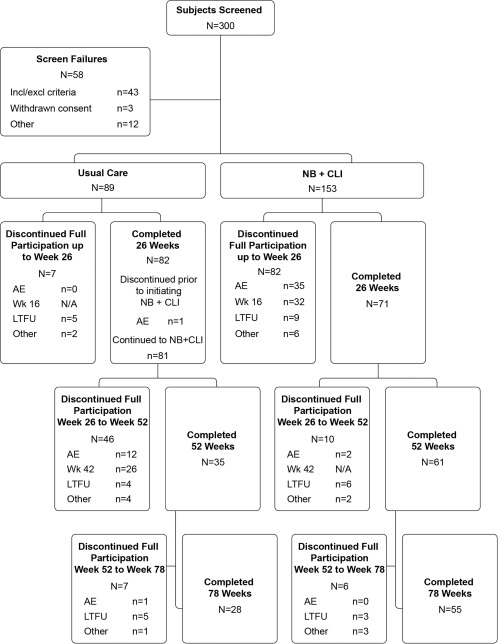

Following a screening period, subjects were randomized in a 1.75:1 ratio to receive either open‐label active study medication (NB) along with CLI (NB + CLI) or usual care for 26 weeks (Figure 1). In accordance with prescribing information, subjects randomized to NB + CLI initiated treatment with NB at a daily dose of 8 mg naltrexone/90 mg bupropion and escalated their dose over the subsequent 3 weeks. In addition, an evaluation of weight loss was performed in the NB + CLI group at week 16, with subjects discontinued from NB if they had not lost at least 5% of their baseline body weight. Additionally, subjects were to discontinue NB if they experienced increases in systolic or diastolic blood pressure of ≥10 mm Hg at both week 10 and week 16.

Figure 1.

Study participants and group assignments. A total of 242 subjects were randomly assigned 1.75:1 to NB + CLI and usual care groups, all of whom were also treated and included in the intent‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis. AE, adverse event; LTFU, lost to follow‐up; other, protocol deviation or withdrawal of consent; N/A, not applicable; NB + CLI, naltrexone/bupropion and comprehensive lifestyle intervention; week 16, evaluation to continue treatment at week 16 visit; week 42, evaluation to continue treatment at week 42 visit.

Uncontrolled treatment period (week 26‐week 78)

After the controlled treatment period of 26 weeks, subjects in the NB + CLI group continued their open‐label NB use and participation in the CLI program. Subjects in the usual care group were switched to open‐label NB use and began participation in the CLI program. These subjects also underwent a weight loss and blood pressure evaluation 16 weeks after beginning NB use (at week 42), and treatment was discontinued, if necessary, based on the same criteria used for subjects originally assigned to NB + CLI.

Sample size determination

Based on the predicted difference in discontinuation rates and effect of a week 16 weight assessment, a randomization ratio of 1.75:1 was adopted. A total of 242 subjects were sufficient to provide ≥90% power to detect a significant difference (α = 0.05) between the treatment groups at week 26 for the per protocol (PP) population using a two‐sample t‐test assuming a true mean difference of 0.6 common standard deviation (SD). The assumptions are based on data from the NB phase 3 trials and publications pertaining to usual care for obesity 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23.

Study end points

The primary end point was the percent change in body weight from baseline (day 1) to week 26, while the secondary end points were percentage of subjects achieving a loss of at least 5%, 10%, or 15% of baseline body weight at week 26. Additional study end points included changes in body weight, vital signs, and obesity‐related risk factors from baseline to post‐baseline visits (both before and after week 26). Patient‐reported outcomes concerning weight‐related quality of life, binge eating, and sexual function were assessed but are not reported in this article.

Statistical analysis

The primary analysis of the primary end point was based on the adjusted least‐squares (LS) means estimated using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), using the week 26 PP population (defined as modified intent‐to‐treat [mITT] subjects in compliance with the protocol in the controlled treatment period), with no imputation of missing data. As sensitivity analyses, the primary end point was also analyzed for the mITT population (defined as randomized subjects with at least one post‐baseline body weight measurement while still on treatment) using mixed model repeated measures (MMRM) and last observation carried forward (LOCF). The week 78 analysis of percent change in body weight was conducted similarly with the primary analysis being ANCOVA in the week 78 PP population (subjects in compliance with the protocol throughout the study) and numerous sensitivity analyses.

Categorical analysis of number and percentage of subjects in the week 26 PP population achieving a loss of at least 5%, 10%, or 15% of baseline body weight at week 26 was assessed using a logistic regression model with a factor for treatment group and baseline BMI category with baseline body weight as a covariate. For treatment comparisons, odds ratios, 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the odds ratios, and P values are reported. Analyses were repeated at week 78 in the week 78 PP population. Other continuous variables were analyzed similarly to the primary end point. Data were only descriptively summarized beyond the controlled treatment period.

All statistical tests were performed two‐sided at the 0.05 level of significance. Adverse events (AEs) were summarized in the ITT population and vital signs were collected for the week 78 PP population. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS® software (Version 9.3, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Baseline characteristics and subject disposition

A total of 242 subjects were randomized and treated (ITT): 153 subjects to the NB + CLI group and 89 subjects to the usual care group (Figure 1). Subject demographics are summarized in Table 1. Of the 242 randomized subjects, 153 subjects (71 in the NB + CLI group and 82 in the usual care group) completed the 26‐week controlled treatment period. The most common reason for discontinuation from the NB + CLI treatment regimen within the first 26 weeks was AEs (n = 35 of 153, 22.9%), followed by discontinuation due to the week 16 assessment (n = 32 of 153; 20.9% [n = 29 did not satisfy the weight criteria alone, n = 1 had blood pressure elevations that met the criteria for discontinuation alone, and n = 2 were discontinued due to both weight and blood pressure criteria]). The most common reason for discontinuation of usual care treatment was lost to follow‐up (n = 5, 5.6%).

Table 1.

Subject demographic and baseline characteristics

| Parameter |

Usual care/NB + CLI (N = 89) |

NB + CLI (N = 153) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (y), mean (SD) | 47.0 (9.98) | 46.1 (9.66) |

| Sex, (% female) | 86.5 | 81.7 |

| Race (%) | ||

| White | 71.9 | 81.0 |

| Black or African American | 27.0 | 18.3 |

| Asian | 0.0 | 0.7 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1.1 | 0.0 |

| Ethnicity (%) | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 5.6 | 2.6 |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 94.4 | 97.4 |

| Weight (kg), mean (SD) | 100.2 (16.58) | 101.4 (15.09) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 36.26 (4.36) | 36.33 (4.20) |

| BMI category (%) | ||

| <30 kg/m2 | 5.6 | 2.0 |

| <35 kg/m2 | 46.1 | 45.8 |

| ≥35 to <40 kg/m2 | 31.5 | 32.0 |

| ≥40 kg/m2 | 22.5 | 22.2 |

| Waist circumference (cm), mean (SD) | 111.9 (11.91) | 112.2 (11.23) |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL), mean (SD) |

n = 86 114.8 (54.40) |

n = 147 131.0 (70.09) |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL), mean (SD) |

n = 84 118.0 (26.17) |

n = 147 115.5 (27.63) |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL), mean (SD) |

n = 84 50.4 (12.75) |

n = 147 50.7 (11.38) |

| Glucose (mg/dL), mean (SD) |

n = 86 92.4 (11.46) |

n = 147 89.7 (10.56) |

| Insulin (uIU/mL), mean (SD) |

n = 84 17.3 (10.68) |

n = 147 19.5 (19.65) |

| HOMA‐IR, mean (SD) |

n = 84 4.07 (2.96) |

n = 147 4.41 (5.01) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg), mean (SD) | 120.6 (11.41) | 123.7 (9.51) |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg), mean (SD) | 78.8 (7.60) | 80.4 (7.26) |

| Heart rate (bpm), mean (SD) | 69.8 (8.68) | 70.9 (8.66) |

BMI, body mass index; CLI, comprehensive lifestyle intervention; HDL, high‐density lipoprotein; HOMA‐IR, homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance; LDL, low‐density lipoprotein; NB, naltrexone/bupropion; SD, standard deviation.

During the uncontrolled treatment period, the most common reason for discontinuation of the usual care/NB + CLI group was the week 42 assessment (n = 26 of 89, 29.2%). Of subjects from the original NB + CLI group, n = 16 discontinued after week 26. No subjects discontinued NB due to an AE with an onset after the first 26 weeks of NB use.

Treatment with NB + CLI led to greater weight loss than usual care

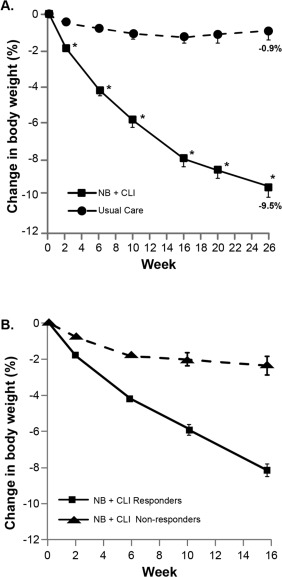

Subjects in the PP population treated with NB + CLI demonstrated a significant decrease in body weight compared with those in the usual care group after 26 weeks (9.46% reduction in the NB + CLI group; 0.94% reduction in the usual care group; 8.52% difference, P < 0.0001) (Figure 2A). When all NB + CLI subjects were included in the analysis using MMRM or LOCF methodology, including those who did not achieve weight loss of 5% at week 16, the reduction in the NB + CLI group relative to usual care at 26 weeks was 5.17% (MMRM) and 4.15% (mITT‐LOCF) (P < 0.0001 in both sensitivity analyses). Changes in weight over the first 16 weeks were analyzed in subjects who achieved 5% weight loss at week 16 (responders) compared with those who did not achieve this threshold (nonresponders, including those who discontinued study medication before week 16) (Figure 2B). This figure demonstrates that the weight loss curves of these two populations separated at the first time point assessed (2 weeks).

Figure 2.

Change in body weight over time. (A) In the week 26 PP population, subjects in the NB + CLI treatment group (squares) lost a significantly higher percentage of baseline body weight compared with those in the usual care group (circles) beginning at the week 2 assessment and continuing through week 26. *P < 0.0001 for LS mean difference between treatment groups. (B) Observed changes in body weight between weeks 0 and 16 in all subjects in the NB + CLI treatment group who either responded (squares) or did not respond (triangles) to NB by losing at least 5% of their initial body weight at week 16. In both panels panels A and B, LS mean and SE are displayed.

Consistent with the greater percentage body weight reduction observed in the NB + CLI group, significantly more NB + CLI subjects achieved each weight loss threshold than usual care subjects at week 26 (84.5% NB + CLI vs. 12.2% usual care had ≥5% weight loss [P < 0.0001]; 42.3% NB + CLI vs. 3.7% usual care had ≥10% weight loss [P < 0.0001]; 12.7% NB + CLI vs. 0% usual care had ≥15% weight loss [P value cannot be determined]) (Table 2), indicating that while there are some subjects who are able to achieve these categorical weight loss values even with very basic advice, the combination of pharmacotherapy and more consistent lifestyle instruction dramatically increases a patient's likelihood of success.

Table 2.

Subjects who achieved a weight loss of at least 5%, 10%, or 15% of body weight at week 26

| Usual care (N = 82) | NB + CLI (N = 71) | |

|---|---|---|

| ≥5% weight loss at week 26, n (%) | 10 (12.2) | 60 (84.5) |

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | 44.0 (16.6 to 116.3) | |

| P | <0.0001 | |

| ≥10% weight loss at week 26, n (%) | 3 (3.7) | 30 (42.3) |

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | 21.4 (6.0 to 76.7) | |

| P | <0.0001 | |

| ≥15% weight loss at week 26, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (12.7) |

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | N/D | |

| P | N/D |

P value for testing the null hypothesis that the odds ratio equals 1 from a logistic regression model with a factor for treatment group and for baseline body mass index category and baseline body weight as a covariate.

CI, confidence interval; CLI, comprehensive lifestyle intervention; NB, naltrexone/bupropion; N/D, not determined.

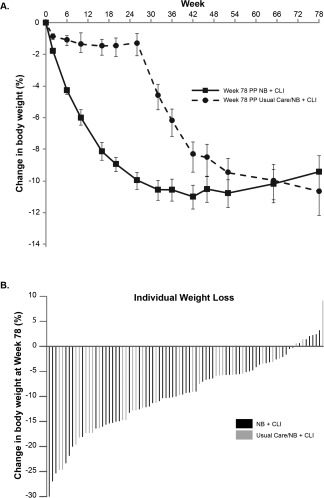

After week 26, when the subjects in the usual care group began treatment with NB + CLI, a similar pattern of weight loss was observed as previously observed in those initially randomized to NB + CLI (Figure 3A), with approximately 90% of the maximum weight loss in each cohort observed over the first 6 months of NB treatment. Changes in weight at week 78 were similar between those who received 52 and 78 weeks of NB + CLI treatment. The change in body weight from baseline to week 78 for each subject who remained in the study is also presented graphically in Figure 3B, highlighting the range of weight changes observed in the population, even when the week 16 criteria was used to select for responders.

Figure 3.

Percentage of body weight lost through week 78. (A) Weight lost by subjects in the NB + CLI group and the usual care/NB + CLI group at week 78. Subjects in the NB + CLI group (squares) lost 90% of their maximum weight lost by 6 months. Subjects in the usual care/NB + CLI group (circles) had lost comparable body weight percentages to those of the NB + CLI group by week 78, despite beginning NB + CLI treatment at week 26. (B) Overall weight lost by individual subjects at week 78.

Obesity‐related risk factors

In addition to the greater reductions in weight observed with NB + CLI compared with usual care at week 26, subjects in the NB + CLI group had significantly greater reductions in triglycerides, waist circumference, glucose, insulin, and a measure of insulin resistance, as well as a significantly greater increase in high density lipoprotein cholesterol (Table 3). At week 78, these changes were generally maintained in subjects who received long‐term treatment with NB + CLI, as shown by the pooled data from all subjects.

Table 3.

Changes in obesity‐related risk factors

| Usual care (N = 82) | NB + CLI (N = 71) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LS mean change (SE) from baseline at week 26 | |||

| Waist (cm) | −1.6 (0.66) | −7.0 (0.71) | <0.0001 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 2.8 (4.63) | −13.6 (4.96) | 0.0019 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 0.1 (0.73) | 4.1 (0.77) | 0.0001 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | −1.9 (2.11) | −2.0 (2.20) | 0.9686 |

| Fasting plasma glucose (mg/dL) | 1.6 (0.96) | −2.9 (1.04) | 0.0016 |

| Fasting insulin (µIU/mL) | −3.4 (0.76) | −7.5 (0.79) | 0.0004 |

| HOMA‐IR | −0.8 (0.19) | −2.0 (0.20) | 0.0003 |

| Mean change (SE) from baseline at week 78 (all subjects with week 78 data) (N = 83) | |||

| Waist (cm) | −7.5 (0.81) | ||

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | −12.4 (8.17) | ||

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 7.0 (0.94) | ||

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 0.3 (2.32) | ||

| Fasting plasma glucose (mg/dL) | −0.8 (1.10) | ||

| Fasting insulin (µIU/mL) | −7.9 (2.51) | ||

| HOMA‐IR | −1.9 (0.67) | ||

P value for ANCOVA LS mean difference between treatment groups.

CLI, comprehensive lifestyle intervention; HDL, high‐density lipoprotein; HOMA‐IR, homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance; LDL, low‐density lipoprotein; LS, least squares; SE, standard error.

Safety results

Safety and tolerability of NB was thoroughly studied in the phase 3 trials, therefore only AEs leading to discontinuation of study medication and serious AEs (SAEs) were collected. AEs leading to NB discontinuation were similar between subjects who initially were randomized to NB + CLI and to subjects originally randomized to usual care who began treatment with NB after week 26; data are therefore presented for the two groups combined in Table 4. Gastrointestinal and neuropsychiatric side effects, known to be associated with NB pharmacology, contributed to 82% of AEs in both treatment groups and tended to occur within the first 4 weeks of treatment. The most frequent AEs that led to discontinuation of NB for the two groups combined included nausea (7.0%), anxiety (2.1%), headache (1.7%), dizziness (1.2%), and insomnia (1.2%). All AEs leading to discontinuation from the NB + CLI group had onset dates before week 26. Two subjects experienced SAEs that were deemed not related to NB by the investigator (breast cancer, one case diagnosed 3 months into NB treatment and the other 1 year after NB treatment had been discontinued).

Table 4.

Overview of treatment‐emergent adverse events and serious adverse events

| Usual care/NB + CLI (N = 89) | NB + CLI (N = 153) | |

|---|---|---|

| Subjects with a TEAE leading to discontinuation from full participation, n (%) | ||

| Before week 26 | 1 (1.1) | 35 (22.9) |

| On or after week 26 and before week 52 | 12 (13.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| On or after week 52 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Entire study | 14 (15.7) | 37 (24.2) |

| Subjects with a SAE, n (%) | ||

| Before week 26 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) |

| On or after week 26 and before week 52 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) |

| On or after week 52 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Entire study | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.3) |

CLI, comprehensive lifestyle intervention; NB, naltrexone/bupropion; SAE, serious adverse event; TEAE, treatment‐emergent adverse event.

Systolic and diastolic blood pressure and heart rate were collected over time to further evaluate the safety of NB treatment. Mean (standard error, SE) systolic blood pressure decreased by 2.2 (2.0) and 2.7 (1.4) mm Hg from baselines of 120.9 and 126.0 mm Hg in the usual care (N = 28) and NB + CLI (N = 55) groups, respectively, at week 78. Mean (SE) diastolic blood pressure decreased by 0.3 (1.6) and 1.7 (1.0) mm Hg from baselines of 78.5 and 80.9 mm Hg, respectively. Mean heart rate changed less than one beat per minute in either group.

Discussion

In this randomized, open‐label study, treatment with 32 mg naltrexone SR/360 mg bupropion SR (NB + CLI) as indicated by its prescribing information was shown to result in approximately 10% weight loss from baseline over a 26‐week period, which was approximately 8.5% more than was observed with usual care, a diet and exercise advice program designed to reflect what a patient might receive in a primary care setting. In this study, subjects who did not achieve at least 5% body weight reduction by 16 weeks of use (i.e., those who did not respond to treatment) or had a sustained elevation in blood pressure were discontinued from study medication. In those who remained on medication through 78 weeks, longer than the observation periods of previous NB studies (56 weeks) 18, 19, 20, 21, the initial weight loss observed at 26 weeks was sustained.

This study, conducted to approximate the real‐world experience, is consistent with and builds on the results of the previous NB phase 3 trials, all of which demonstrated that NB used as an adjunct to lifestyle modification is associated with weight loss of approximately 4% to 5% greater than seen with placebo subjects receiving the same lifestyle intervention in subjects with overweight or obesity 18, 19, 20, 21. The previous studies did not prospectively utilize an efficacy assessment at week 16 of NB treatment and were limited to a 56‐week duration. This study assessed the effects of NB in the population of subjects who responded to the medication by losing at least 5% of their initial body weight by 16 weeks, and demonstrated that NB + CLI associated weight loss were maintained over 78 weeks. The safety profile was also consistent with previous studies: most subjects tolerated NB well, and those who developed AEs did so early in the treatment protocol. The most common AE leading to NB discontinuation was nausea (7.0% of all subjects), which is consistent with the rate in the phase 3 trials (6.3%). While the mechanism by which NB causes nausea is unknown, it was demonstrated in the phase 3 trials that nausea tends to occur early in treatment, is primarily mild to moderate in severity, and is not a major contributor to weight loss 24. Only two AEs led to discontinuation in the NB + CLI group after week 26 (both with AE onset before week 26), and no AEs necessitating discontinuation had an onset date during the extended time period (weeks 52‐78). These results strengthen the body of evidence suggesting combination therapy of NB along with lifestyle to promote weight loss is a promising approach to lowering the prevalence of obesity.

The evaluation for body weight reduction of 5% at week 16 (after 12 weeks at full dose NB) is in line with product labeling. The recommendation to discontinue due to sustained blood pressure increases of 10 mm Hg at week 16 in the present study was more specific than product labeling, which recommends monitoring at regular intervals and discontinuing NB if concerns about increased blood pressure are present. In this real‐world setting, 67% (72 of 107) of NB + CLI subjects who received study medication for 16 weeks responded to the medication per the evaluation criteria used in the present study. Similarly, 57% (37 of 65) of usual care/NB + CLI subjects who received study medication for 16 weeks met the early evaluation threshold. The overwhelming majority of discontinuations at week 16 were due to insufficient weight loss relative to baseline (more than 90% of the discontinuations in each treatment group) rather than adverse blood pressure effects.

An advantage of various sensitivity analyses (MMRM and LOCF) is to demonstrate the robustness of the conclusion from the primary analysis in the PP population. In the present manuscript, the planned sensitivity analyses confirmed the positive findings in efficacy, while also allowing contribution of the earlier data from subjects who were discontinued at the week 16 weight assessment.

A major caveat of this study is inherent to its design. In order to test NB effects in a manner consistent with the label, continued study participation in the NB treatment group was limited to those who responded to the drug, whereas no such limitation applied to the control group. Other limitations of the present study include its open‐label nature, the uncontrolled nature of the extension time period, and the high number of dropouts. The NB phase 3 trials were specifically designed to test the effects of NB, and thus utilized a common lifestyle intervention program in both NB and placebo groups. This study design compared lifestyle intervention that can be considered standard in clinical care (i.e., encouragement to lose weight, educational materials, and tools designed to enable weight loss, but without regular, consistent reinforcement of the behavior change), against a more supportive lifestyle intervention combined with NB treatment that followed the prescribing information whereby treatment could only be continued if at least 5% weight loss was observed after 12 weeks of treatment with the full dose (16 weeks after start of treatment). The lack of a CLI group without study medication could be viewed as a limitation, as one cannot estimate the contribution from each component of the weight loss assistance provided (NB vs. CLI), but based on the phase 3 trials, the effect of NB above that of a placebo plus lifestyle intervention ranged from 3.68% 20 in patients with type 2 diabetes to 6.24% in a more general obesity population 19.

Conclusion

Treatment with 32 mg naltrexone SR/360 mg bupropion SR (NB) as indicated by the prescribing information and along with a CLI significantly improved weight loss relative to usual care alone. The efficacy was maintained for at least 78 weeks, a longer duration than has been previously studied. The results of this study reflect what may be expected to occur in real‐world clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Thomas Wadden for his participation in study design and thoughtful review of the manuscript, as well as the subjects, study team, and the study sites for their participation. Editorial assistance was provided by Medical Dynamics.

Funding agencies: Orexigen Therapeutics, Inc.

Disclosure: AH, KS, and KG are Orexigen Therapeutics employees and stockholders. BW was an Orexigen Therapeutics employee and remains a stockholder. KF is a consultant for Orexigen Therapeutics.

Author contributions: AH and BW were involved in the conception and design of the study, and KF contributed to study design. AH, KS, BW, and KG were involved with data acquisition, and KS and KG provided statistical analysis. All authors were involved with data interpretation, participated in writing and revising the manuscript, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Clinical trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01764386.

References

- 1. Bays HE, Gonzalez‐Campoy JM, Bray GA, et al. Pathogenic potential of adipose tissue and metabolic consequences of adipocyte hypertrophy and increased visceral adiposity. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 2008;6:343‐368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among US adults, 1999‐2010. JAMA 2012;307:491‐497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011‐2012. JAMA 2014;311:806‐814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. World Health Organization . Obesity. 2013. www.euro.who.int/obesity. Accessed November 26, 2016.

- 5. Finkelstein EA, Trogdon JG, Cohen JW, Dietz W. Annual medical spending attributable to obesity: payer‐and‐service‐specific estimates. Health Aff 2009;28:w822‐w831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Haslam DW, James WP. Obesity. Lancet 2005;366:1197‐1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Olshansky SJ, Passaro DJ, Hershow RC, et al. A potential decline in life expectancy in the United States in the 21st century. N Engl J Med 2005;352:1138‐1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Padwal RS, Majumdar SR. Drug treatments for obesity: orlistat, sibutramine, and rimonabant. Lancet 2007;369:71‐77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Morton GJ, Cummings DE, Baskin DG, Barsh GS, Schwartz MW. Central nervous system control of food intake and body weight. Nature 2006;443:289‐295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cone RD, Cowley MA, Butler AA, Fan W, Marks DL, Low MJ. The arcuate nucleus as a conduit for diverse signals relevant to energy homeostasis. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2001;25(Suppl 5):S63‐S67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cowley MA, Smart JL, Rubinstein M, et al. Leptin activates anorexigenic POMC neurons through a neural network in the arcuate nucleus. Nature 2001;411:480‐484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dhillon S, Yang LP, Curran MP. Bupropion: a review of its use in the management of major depressive disorder. Drugs 2008;68:653‐689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Saper CB, Chou TC, Elmquist JK. The need to feed: homeostatic and hedonic control of eating. Neuron 2002;36:199‐211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Anderson JW, Greenway FL, Fujioka K, Gadde KM, McKenney J, O'Neil PM. Bupropion SR enhances weight loss: a 48‐week double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Obes Res 2002;10:633‐641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Greenway FL, Whitehouse MJ, Guttadauria M, et al. Rational design of a combination medication for the treatment of obesity. Obesity 2009;17:30‐39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jain AK, Kaplan RA, Gadde KM, et al. Bupropion SR vs. placebo for weight loss in obese patients with depressive symptoms. Obes Res 2002;10:1049‐1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sinnayah PWN, Evans AE, Cowley MA. Bupropion and naltrexone interact synergistically to decrease food intake in mice. Obesity 2007;15:A179. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Apovian CM, Aronne L, Rubino D, et al. A randomized, phase 3 trial of naltrexone SR/bupropion SR on weight and obesity‐related risk factors (COR‐II). Obesity 2013;21:935‐943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Greenway FL, Fujioka K, Plodkowski RA, et al. Effect of naltrexone plus bupropion on weight loss in overweight and obese adults (COR‐I): a multicentre, randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2010;376:595‐605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hollander P, Gupta AK, Plodkowski R, et al. Effects of naltrexone sustained‐release/bupropion sustained‐release combination therapy on body weight and glycemic parameters in overweight and obese patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2013;36:4022‐4029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wadden TA, Foreyt JP, Foster GD, et al. Weight loss with naltrexone SR/bupropion SR combination therapy as an adjunct to behavior modification: the COR‐BMOD trial. Obesity 2011;19:110‐120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wadden TA, Volger S, Sarwer DB, et al. A two‐year randomized trial of obesity treatment in primary care practice. N Engl J Med 2011;365:1969‐1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tsai AG, Wadden TA, Rogers MA, Day SC, Moore RH, Islam BJ. A primary care intervention for weight loss: results of a randomized controlled pilot study. Obesity 2010;18:1614‐1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hong K, Herrmann K, Dybala C, Halseth AE, Lam H, Foreyt JP. Naltrexone/bupropion extended release‐induced weight loss is independent of nausea in subjects without diabetes. Clin Obes 2016;6:305–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]