Abstract

Background:

Cartilage is an important tissue found in a variety of anatomical locations. Damage to cartilage is particularly detrimental, owing to its intrinsically poor healing capacity. Current reconstructive options for cartilage repair are limited, and alternative approaches are required. Biomaterial science and Tissue engineering are multidisciplinary areas of research that integrate biological and engineering principles for the purpose of restoring premorbid tissue function. Biomaterial science traditionally focuses on the replacement of diseased or damaged tissue with implants. Conversely, tissue engineering utilizes porous biomimetic scaffolds, containing cells and bioactive molecules, to regenerate functional tissue. However, both paradigms feature several disadvantages. Faced with the increasing clinical burden of cartilage defects, attention has shifted towards the incorporation of Nanotechnology into these areas of regenerative medicine.

Methods:

Searches were conducted on Pubmed using the terms “cartilage”, “reconstruction”, “nanotechnology”, “nanomaterials”, “tissue engineering” and “biomaterials”. Abstracts were examined to identify articles of relevance, and further papers were obtained from the citations within.

Results:

The content of 96 articles was ultimately reviewed. The literature yielded no studies that have progressed beyond in vitro and in vivo experimentation. Several limitations to the use of nanomaterials to reconstruct damaged cartilage were identified in both the tissue engineering and biomaterial fields.

Conclusion:

Nanomaterials have unique physicochemical properties that interact with biological systems in novel ways, potentially opening new avenues for the advancement of constructs used to repair cartilage. However, research into these technologies is in its infancy, and clinical translation remains elusive.

Keywords : Arthroplasty, Biomaterials, Cartilage, Cartilage-tissue-engineering, Nanomaterials, Nanotechnology, Osteoarthritis, Tissue-engineering

1. INTRODUCTION

Cartilage is a multifunctional, specialized tissue, found in a variety of important anatomical locations. Histological classification systems describe three forms of human cartilage: hyaline, fibrous and elastic [1]. Hyaline cartilage is firm but compliant, and primarily covers the articular surfaces of bone, where it serves as a frictionless, load-bearing surface that resists local mechanical stress [1]. It also serves an important role in the respiratory system, maintaining tracheal and nasal patency, while permitting dynamic alterations to airway calibre [1]. Fibro-cartilage is a tough, inelastic material that is found in the knee joint menisci and intervertebral discs, also providing stress resistance [1]. Elastic cartilage is found in the pinna, Eustachian tubes and epiglottis, imparting flexibility and support to these structures [1].

Damage to any of the aforementioned areas is particularly detrimental, as cartilage is avascular, with limited regenerative capacity [2]. Pathology involving cartilage can thus result in significant functional and aesthetic problems, exacerbating the course of a variety of conditions.

Osteoarthritis is a key example. It is associated with degeneration of articular cartilage, afflicting an estimated 27 million adults in the United States alone [3, 4]. The prevalence of osteoarthritis is progressively increasing [5, 6], exerting a substantial socioeconomic burden on patients and healthcare systems [7]. In addition, defects in craniofacial cartilage can be observed following trauma, malignancy, and in congenital anomalies, such as microtia [8-10]. Diseases involving tracheal cartilage can result in devastating airway stenosis, a constant threat to life [11]. Cartilage repair is therefore of multidisciplinary importance.

Current reconstructive options for these conditions have limitations. Replacement of damaged regions with implants eventually ends with material failure or extrusion. Autologous grafts result in donor site morbidity, and in the case of ear reconstruction, require considerable labour and expertise to design. The requirement for graft revision often results in multiple surgeries. There is thus an appreciable necessity for novel approaches to cartilage replacement, which overcome these drawbacks.

Regenerative medicine encompasses several areas of research that drive advancements in tissue reconstruction technology. Recent advances involve the integration of nanotechnology and regenerative medicine constructs, facilitating the development of novel “nanomaterials” for bioengineering purposes (see section 3.1. for more details). This review aims to summarize current strategies for the restoration of functional cartilage, introduce the concept of nanomaterials in regenerative medicine, and discuss the relative advantages and disadvantages of using biomimetic nanomaterials for cartilage repair.

2. CURRENT STRATEGIES TO TREAT CARTILAGE DAMAGE

There are two main strategies to restore human tissue: (a.) replacement and (b.) regeneration. Several fields approach restoration of cartilage from either paradigm. Cell Therapy, Biomaterials Science and Tissue Engineering are popular options to manage cartilaginous defects.

2.1. Cell Therapy

Cell therapy aims to regenerate lost cartilage via the local delivery of an appropriate cell population. In the case of articular disease, marrow stimulating procedures involving subchondral drilling or microfracture of articular bone have been developed to promote migration of pluripotent progenitor cells into damaged areas [12, 13]. However, due to the lack of biological cues to direct cell behaviour, fibrocartilage can form in treated areas instead of hyaline cartilage, resulting in suboptimal function [14]. In addition, microfracturing subchondral bone results in cyst formation, making the bone underlying regenerated cartilage fragile and brittle [14]. These techniques are used mainly in lesions smaller than 4cm2, and it is unclear whether they can benefit patients with larger areas of damage [14]. A recent meta-analysis by Goyal et al. noted long-term treatment failure with microfracture therapy, and recurrence of osteoarthritis 5 years post-operatively [15]. Magnusson et al. noted issues with a lack of randomized control groups in existing clinical trials [16].

Cell therapy is further limited in areas where anatomical complexity is required, such as with reconstruction of the pinna or trachea, due to issues with spatial orientation and local sequestration of cells. Such issues preclude the use of non-surgical cell-based approaches, such as stem cell therapy. Thus, alternative methods are necessary.

2.2. Biomaterials

Biomaterials science traditionally focuses on the replacement of damaged cartilage with synthetic implants, and can be applied to the management of large, complex pathology. A classic example is the use of biomaterials in total joint replacement, commonly carried out for osteoarthritis in the knee and hip [17]. Ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene (UHMWPE) is a well-described material used to engineer total knee replacement systems, while modern hip prostheses feature an additional metal or ceramic femoral head component, which articulates with an UHMWPE acetabular cap [18, 19]. In the craniofacial region, porous high-density polyethylene (Medpor) is a synthetic material used for both nasal and ear reconstruction [20, 21]. The porosity aims to facilitate ingrowth of fibroblasts and endothelial cells, which produce extra cellular matrix (ECM) and a hierarchal vascular network respectively, to better integrate the implant [22]. A variety of other biomaterials are employed in cartilage tissue engineering, which will be discussed in the next section.

There are several advantages offered by the use of biomaterials in reconstructive surgery. Operating time is minimized, as donor sites are not required [22]. In addition, the use of biomaterials obviates the need for graft fabrication, such as in ear reconstruction, which currently requires considerable specialist experience. With recent improvements in computer-aided design and 3D printing technology, novel techniques for high throughput production of medical implants have become more efficient and cost effective [23]. Mass production of customized materials could improve surgical planning and post-operative results. Reconstructive procedures could thus become more accessible to a wider range of patients, especially in rural or economically disadvantaged areas. However, a variety of mechanisms that lead to implant failure must be addressed.

Infection is a common reason for removal of joint prostheses, necessitating revision surgery [24, 25]. Infection and extrusion affect up to 14.8% of Medpor based ear reconstructions [26]. Conversely, aseptic loosening or extrusion of implants can occur, driven by issues with surface and bulk characteristics [25]. A key bulk characteristic that promotes implant loosening is Young’s Modulus: a measure of the stiffness of a material. Modular mismatch between an implant and its anchoring tissue can result in a series of events leading to aseptic loosening. In the case of materials used to replace damaged articular cartilage, implants are anchored to bone. Modular mismatch results in stress shielding of regional bone, leading to osteolysis [27, 28]. Subsequently, micromovement occurs at the interface, leading to loosening of the implant. Material mismatch with native tissue also causes similar problems with Medpor ear implants, contributing not only to micromovement, but also compromising blood flow to the overlying wound, preventing adequate healing [22]. Suboptimal mechanical characteristics can additionally result in wear and fatigue of materials. Wear debris can be disseminated throughout the body, potentiating a chronic inflammatory response [18, 19, 25, 29].

Interactions between the surface of a material and biological systems compound the effects of mismatched bulk properties. When exposed to physiological fluid, the material surface first becomes coated with water, the degree of which is governed by its wettability, and then adsorbs regional peptides, oriented according to surface topography [30]. Adhesive peptides change configuration upon attachment, revealing cryptic motifs that bind to cell receptors, regulating cell attachment, spatial patterning and transduction of signaling proteins [31]. During the acute inflammatory stage following implantation, the cell population promotes fibrous encapsulation of poorly integrated implants, which can contribute to micromovement, loosening and extrusion [32].

Biomaterial implants merely replace deficient cartilage, and cannot adapt or remodel themselves in areas with dynamic stresses. Furthermore, in the case of joint replacement systems, no attempt is made to address the core pathology, deficiency of articular cartilage. Implanted materials can generate auxiliary problems in surrounding tissue, such as bone, which is damaged during replacement procedures. Hence, there are several disadvantages to Biomaterials that necessitate improvement.

2.3. Tissue Engineering

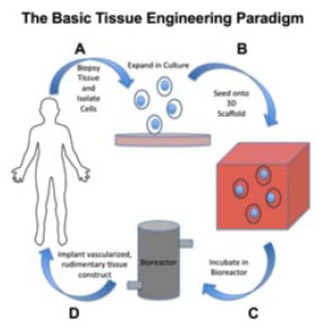

The emerging field of Tissue Engineering holds promise for repairing complex cartilaginous defects. A vital aspect of this area of regenerative medicine is the use of biomaterial scaffolds that accurately replicate the in vivo extra cellular matrix (ECM), permitting encapsulation of cells and bioactive molecules, which regenerate functional tissue. Scaffolds act as a template for cellular patterning and growth, sequestering cells in a target area while providing strength in three dimensions to nascent tissue (Fig. 1).

Fig. (1).

Schematic detailing the basic principles of tissue engineering (human template from http://cliparts.co/clipart/2400013 [online]accessed04/08/14).

Several cell types have been successfully used to engineer tissues with properties similar to native cartilage. Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation (ACI) is a modality that involves ex vivo seeding of scaffolds with autologous chondrocytes prior to placement in vivo [33-36]. Similarly, Multipotent Stromal Cells (MSCs) sourced from autologous tissue biopsies can be utilized, owing to their chondrogenic differentiation potential [37-39]. Platelet rich plasma (PRP), sourced by centrifuging samples of peripheral blood, contains a variety of growth factors, and has been reported to improve chondrogenesis in both ACI and MSC based Tissue Engineering strategies [40-42]. However, prolonged maintenance of the chondrogenic phenotype remains challenging. Multiple cytokines released at specific concentrations, with defined rates, are required for differentiation of cells. Unfortunately, controlled, sequential delivery of growth factors is limited due to their short half-lives [43].

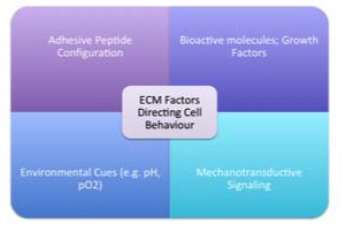

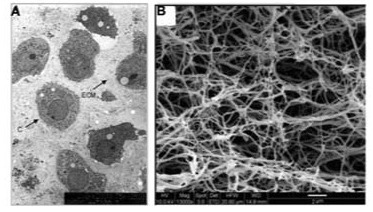

Unlike the bulk biomaterials utilized in total replacement procedures, a variety of porous, bioactive materials are used as Tissue Engineering scaffolds. It is well understood that the native ECM is comprised of interwoven collagen, glycoprotein and glycosaminoglycan nanofibres [44]. Adhesive peptide configuration upon these natural nanofibres guides three-dimensional cellular patterning, and upregulates the assembly of intracellular signaling proteins [45]. Similarly, the reservoir of growth factors and environmental cues influence cell behaviour [44] (Fig. 2).

Fig. (2).

Influence of the ECM on cell behaviour.

Tissue Engineering scaffolds thus aim to recapitulate these features, and mimic the ECM. In general, scaffolds are divided into natural and synthetic types. Natural materials include collagen, fibrin, hyaluronic acid and alginate hydrogels, as well as decellularized tissues. These can be used either as solid, implantable scaffolds, or as injectable Tissue Engineering systems. Synthetic materials include poly-glycolic acid (PGA), poly-L-lactic acid (PLA), poly-L-lactide-caprolactone (PCL) and polyethylene glycol (PEG). Several in vitro studies and animal models have been evaluated using these scaffolds, but the quality of cartilage formed remains questionable [33-39].

Several limitations impede cartilage tissue engineering with conventional constructs. Despite containing significant quantities of bioactive cues and molecular signals, hydrogels lack mechanical strength, impeding load-bearing applications. In addition, they carry risks of disease transmission and immunogenicity, especially if allo- or xenogeneic sources are used [46]. Synthetic materials are less likely to trigger immune rejection, but bring with them the mechanical disadvantages of biomaterials described in the previous section. Indeed, scaffold properties such as surface topography and material stiffness have considerable influence on chondrogenic differentiation and cartilage development. The effect of the former on adhesive peptide patterning and subsequent modulation of cell behaviour has been previously discussed; in the context of Tissue Engineering, surface topography is known to play a key role in chondrogenesis, via its influence on cell patterning [47]. Material stiffness not only affects implant integration, but also impacts cell behaviour via a process termed mechanotransduction [48]. Mechanical forces are generated at sites of cell-matrix adhesions, and are transduced through cytoskeletal proteins that connect membrane peptides to intracellular targets, mediating signaling cascades which alter gene expression [49]. Increasing substrate stiffness has been shown to reduce chondrogenic marker expression [50]. Conflictingly, as substrate stiffness decreases, cellular proliferation decreases [51]. Optimizing material stiffness to ideal levels thus requires fine, precise adjustments.

Developing novel techniques to optimize scaffold properties and growth factor delivery are essential to better propagate chondrogenesis. Considering that the molecular factors involved in tissue regeneration operate within an intricate nanoscale environment, manipulating this environment to overcome the aforementioned challenges is a new focus of bioengineering research [52].

3. NANOMATERIALS FOR CARTILAGE REGENERATION/REPLACEMENT

3.1. An Introduction to Nanomaterials

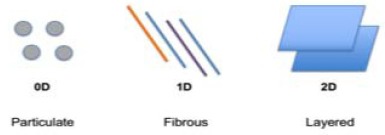

Nanomaterials are defined as materials composed of natural or synthetic components with at least one dimension ranging between 1-100nm [53]. The predominance of quantum mechanical phenomena at the nanoscale produces unique surface and bulk properties that do not manifest at larger scales. There are three main geometric configurations that can be used to categorize nanomaterial components: Particulate (a unit quantity of matter with no dimension outside the nanoscale (0D)), Fibrous (fibres with vertical and horizontal diameters measuring in the nanoscale, but non-nanoscale length (1D - one dimension outside the nanoscale)) and Layered (sheet-like structures with a nanoscale thickness, but length and breadth larger than the nanoscale (2D - two dimensions outside the nanoscale)) [54] (Fig. 3). These have been used in a wide range of biomedical applications, including medical imaging, diagnostics and drug delivery [54].

Fig. (3).

Geometric classification of nanomaterials.

In the context of reconstruction using Biomaterials or Tissue Engineering, a key application of nanomaterials is in the development of nanocomposites. Composite or hybrid materials are traditionally used to generate implants or scaffolds that incorporate the advantageous properties of their individual components, while mitigating their disadvantages [55]. However, conventional composites are based on micrometer-sized fillers that comprise a large area within the bulk material, limiting the efficiency with which selected properties can be influenced [55]. Conversely, Nanomaterials have high surface area to volume ratios, and unique physicochemical properties are present at the material-filler interface [56]. These features allow for dramatic alterations to bulk material properties at much lower filler volumes, creating new avenues by which materials can be modified to better mimic human tissue. Nanocomposites that interact in novel ways within the human body can potentially be used to create implants or scaffolds that overcome the disadvantages described in the previous section, improving our ability to reconstruct damaged cartilaginous structures.

As previously described, cell-peptide interactions at the surface of an implanted material govern the quality of its integration, and in the case of Tissue Engineering scaffolds, guides three-dimensional cellular patterning, differentiation and proliferation. Altering the surface topography of implants at the nanoscale is another way that current materials can be modified [57]. Nanoparticles, nanodots, or even nanoscale grooves have been engineered onto scaffolds using nanolithography to promote cell attachment to scaffold matrices [57]. Similarly, cell-adhesive peptides can be bound to surfaces at the nanoscale to regulate chondrogenesis and selectively control cell-matrix interactions [58]. Top-down manufacturing techniques such as nanolithography, and bottom-up techniques such as Electrospinning represent the latest advances in nanoengineering, making development of novel constructs increasingly feasible [59-61].

In subsequent sections, we will explore current evidence from the literature for how Nanomaterials can improve bio-integration of cartilage-replacing implants, and how cell behaviour in cartilage tissue engineering systems can be optimized using this technology.

3.2. Nanomaterial Applications in Cartilage Replacement

Biomaterial-associated infection remains a significant complication of replacement strategies, especially in orthopaedic surgery [62]. Bacterial adhesion to implants and the subsequent formation of a pathogenic biofilm are key events driving the infectious process [63]. Preventing adhesion of pathogens is a logical tactic to prevent septic failure, but purely anti-adhesive materials are sub-optimal as they could limit implant-host integration. Modification of materials at the nanoscale to create anti-bacterial surfaces has been proposed as a solution. Singh et al. utilized nanostructured titanium surfaces to demonstrate decreased E. coli and Staph. aureus biofilm formation with increasing surface roughness in vitro [64]. It was found that with increasing nanoscale roughness, the larger surface area resulted in increased protein adsorption, with unique morphologies, which likely prevented bacterial adhesion by shielding the surface [64]. Mitnik-Deneva et al. reported similar findings using etched glass substrates, upon which a three-fold decrease in bacterial adhesion was observed with incremental nanoscale roughness [65]. Considering these findings, surface nanopatterning could permit selective attachment of host peptides in vivo, while preventing deleterious bacterial adhesion. However, the process of bacteria-material adhesion is highly complex and other underlying mechanisms must be fully elucidated to improve our understanding of these findings. Moreover, further research is required to characterize this phenomenon with a wider variety of materials.

Another surface modifying technique involves the use of antibacterial nanoparticle coatings. Silver is the most prevalent material used for this purpose, though other metals also exhibit bactericidal properties [66]. Silver nanoparticles disrupt bacterial cell walls, cell membranes and DNA either directly or via generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [67]). The classical approach is to coat implants with nanoparticles using technologies such as electrodeposition [68]. However, concerns surrounding the toxicity potential of unregulated release of silver nanoparticles have driven research into safer delivery mechanisms. For example, De Giglio et al. developed a silver nanoparticle-containing hydrogel coating, which suppressed Staph. aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and E. coli growth in vitro, while preserving osteoblast activity at the titanium implant surface [69]. An alternative method gaining in popularity is the use of silver-containing hydroxyapatite (HA) coatings. Fielding et al. evaluated the efficacy of a silver-strontium-HA nanocomposite coating and demonstrated a bactericidal effect against P. aeruginosa [70]. Chen et al. reported similar findings against Staph. aureus [71]. Nevertheless, these techniques require further long-term investigation using animal models, to thoroughly evaluate their potential harmful effects.

The use of HA to deliver nanoparticles has the added advantage of improving osseointegration at the implant-tissue interface, since HA is an osteoconductive compound [72]. The formation of a robust bond at this interface can assist in minimizing micromovement, and the resultant formation of wear debris. The moderation of implant integration can also be tackled by altering the nanotopography of material surfaces. For example, an in vitro study by Biggs et al. demonstrated the use of disordered nanopits to modulate human osteoblast adhesion [73].

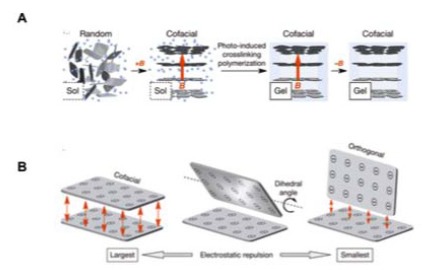

A wide variety of nanocomposites have been developed to optimize the bulk material properties of orthopaedic implants, about which a comprehensive review is available [74]. Despite these advances, stress shielding remains problematic, and the ideal material for total joint replacement is yet to be discovered. Recently, Liu et al. reported the development of a hydrogel containing cofacially oriented titanate nanosheets, with electrostatic repulsive forces maintained between them [75]. The system was developed by polymerizing the hybrid material, while applying a magnetic field to orient nanosheets into maximally electro-repulsive configurations (Fig. 4).

Fig. (4).

A.) Polymerization while a magnetic field is applied fixes nanosheets in desired orientation. B.) Schematic representation of optimal orientation for maximal electrostatic repulsion. Adapted from [75].

The material resists compression, while remaining compliant to shear forces, replicating the role of articular cartilage, overcoming crucial mechanical disadvantages of hydrogels [75]. With further research, this magnetic hydrogel-based nanocomposite system could represent a new approach to joint replacement, avoiding substantial damage to bone by replacing only the lost surface tissue.

In the context of ear reconstruction, a nanocomposite polymer comprised of poly-oligomeric-silsesquioxane nanoparticles incorporated into poly-carbonate-urea (POSS-PCU), has been developed [22]. POSS-PCU has stiffness and Young’s modulus similar to that of native ear cartilage [22]. Fibroblasts seeded onto the porous nanocomposite material in vitro demonstrated higher collagen production and migration than those on Medpor, thereby suggesting that POSS-PCU is a viable alternative to the latter in terms of biointegration [22]. Further in vitro and in vivo research remains to be conducted; other evidence posits that this material may be better suited to Tissue Engineering applications (Section 3.4).

Despite the potential improvements that nanomaterials offer to the replacement strategy for cartilage repair, this remains a suboptimal approach, especially in joint replacement systems. The regeneration of premorbid cartilage via the use of nanomaterials as tissue engineering scaffolds may offer a better alternative.

3.3. Nanomaterial Applications in Cartilage Tissue Engineering

The rationale for using nanomaterials to manufacture Tissue Engineering scaffolds is to better mimic the native ECM and physicochemical properties of desired tissues, thereby optimizing cell attachment, differentiation and proliferation (Fig. 5). While micro-porous scaffolds (μm sized pores) have been traditionally used, they are architecturally dissimilar to the ECM, with corresponding differences in cell behaviour [36].

Fig. (5).

A.) Microporous scaffold architecture [36]. B.) Nanofibrous scaffold architecture [83]. The architecture of the nanofibrous scaffold better resembles the native Extracellular Matrix.

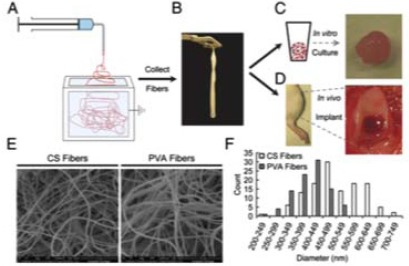

Electrospun nanofibres have recently gained traction for potential Tissue Engineering applications, reportedly inducing continuous chondrogenic differentiation in vitro [76]. Electrospinning is a technique that uses an electric charge to generate streams of electrostatically charged liquid. Charges result in repulsive forces that elongate and thin streams as they dry, forming fibres with nanoscale dimensions [77]. Coburn et al. engineered a PCL nanofibre/PEG-hydrogel nanocomposite using Electrospinning, and cultured bone-marrow-derived-MSCs upon the nanofibrous scaffold [78] (Fig. 6). It was reported that cells seeded upon the composite scaffolds exhibited diverse stellate morphology, comparable to that of natural tissue, whereas those cultured in the hydrogel alone were rounded and homogenous [78]. ECM synthesis was increased in the nanocomposite, but the system was not used to engineer cohesive cartilage tissue [78]. In a separate study, the same author also engineered a Polyvinylalcohol-methacrylate (PVA-MA)/Chondroitin Sulphate (CS) nanofibre composite, which demonstrated increased chondrogenesis when seeded with MSCs, compared to PVA alone, using gene expression analysis [79]. These findings were replicated in vivo using murine osteochondral disease models. However, the cartilage produced in this study was only reported to “resemble” hyaline cartilage, and further research is warranted to improve tissue quality.

Fig. (6).

Coburn et al. experimental design: A & B.) Electrospinning nanofibres; C & D.) Bone-marrow-derived MSCs cultured and implanted into an in vivo animal model; E&F.) SEM of nanofibres and fibre sizes (Adapted from [79]).

Phase separation is an alternative manufacturing technique that produces 3D nanofibrous scaffolds with high precision. Briefly, the process involves a thermal cycling process that splits a polymer blend into separate polymer and solvent phases, based on different thermoresponsive kinetics [80-82]. The separated components are rapidly cooled and freeze-dried to remove the solvent phase, leaving behind an intricate porous nanofibre network [80, 82]. Phase separation was utilized by Liumin He et al. to create a PCL/PLLA nanocomposite scaffold [83]. Chondrocytes seeded onto nanofibrous scaffolds exhibited increased proliferation as well as higher collagen type 2 and aggrecan gene expression when compared with solid-walled scaffolds in vitro [83]. In addition, cells maintained a chondrocyte-like phenotype for a longer duration when cultured upon the nanofibrous scaffold [83]. Xue et al. conducted an in vivo study using an MSC seeded, phase separated PLGA/HA nanocomposite, which demonstrated formation of “hyaline-like” cartilage after twelve weeks [84]. Teoh et al. used phase separation to engineer a POSS-PCU and POSS-PCL hybrid scaffold for tracheal Tissue Engineering [85]. Quantum dots were conjugated to cell-binding peptides to monitor cell migration. The prototype exhibited robust MSC adhesion and proliferation, both on the surface and within the pores [85]. However, the authors did not report whether cells successfully maintained a chondrocytic phenotype following differentiation.

Altering the surface topography of materials at the nanoscale to influence cell aggregation and adhesion is another method to promote chondrogenesis (see section 2.3). Kay et al. developed a preliminary technique to introduce nanopatterns onto material surfaces [86]. In this study, NaOH was used to chemically etch the surface of a PLGA-titanium nanocomposite, upon which increased chondrocyte adhesion was observed. Since this preliminary finding, a variety of nanopatterning methods have been reported in the literature. When considering scaffolds with interconnected porous architectures, surface modification includes the pore surfaces, and therefore extends in three dimensions. As described previously, POSS-PCU is a nanocomposite polymer with similar mechanical properties to ear cartilage [22]. The inclusion of POSS nanoparticles modifies the surface nanotopography of PCU. Oseni et al. cultured ovine septal chondrocytes upon both POSS-PCU and PCL substrates, and demonstrated increased cell viability and proliferation upon the nanocomposite [87]. More recently, Guasti et al. seeded POSS-PCU with adipose-derived MSCs, and reported excellent cell survival, intra-pore migration and chondrogenic differentiation within the scaffold [88]. However, the formation of cohesive hyaline cartilage tissue was not attempted. In vivo studies using this material remain to be published.

A variety of other surface nanopatterning techniques are yet to be successfully trialed in the engineering of cartilage tissue engineering constructs. A key application would be towards the immobilization of (Arg-Gly-Asp) RGD cell adhesive peptides upon material surfaces [89]. The native ECM is a reservoir of RGD adhesive peptides, which bind cell membrane integrin proteins to specific regions, and mediate intracellular signaling [45]. Variation in RGD orientation and density at the nanoscale affects both cell adhesion and motility [45]. Accurately mimicking RGD-matrix patterning using nanotechnology remains a challenging prospect, as molecular adsorption has traditionally been limited to the microscale. Cavalcanti et al. tackled this issue by utilizing nanolithography to pattern gold nanodots coated with RGD onto a glass substrate, and managed to control and direct fibroblast adhesion dynamics [90, 91]. Increasing the nanoscale density of RGD was shown to promote cell adhesion and spreading, by stabilizing integrins and rate of focal adhesion formation [91]. Similar techniques could be applied to cartilage tissue engineering scaffolds to optimize cellular patterning.

A major limitation of existing Tissue Engineering scaffolds is regulating the delivery of growth factors within constructs. Transforming Growth Factor β (TGFβ) isoforms, basic Fibroblast Growth Factor (bFGF) and Insulin-like Growth Factor (IGF) are key cytokines for chondrogenic differentiation [92]. Cytokines need to be released in specific sequences, with defined rates, for ordered differentiation of cells [92]. Growth factor delivery within scaffolds can be optimized using biodegradable gelatin-based microspheres, which can be incorporated with a variety of nanoparticles. Microspheres containing TGFβ3 nanoparticles to promote chondrogenesis have been successfully engineered [93]. Similarly, chitosan microspheres containing TGFβ1 were successfully used to enhance neocartilage formation within a natural composite scaffold [94]. Zhu et al. developed microspheres for the controlled delivery of bFGF, sustained over a period of 2 weeks [95]. These microspheres can be sequestered within Tissue Engineering scaffolds to be used as vehicles for local delivery and controlled release of chondrogenic cytokines [93, 96]. Altering the degree of cross-linking changes degradation rates, thereby modifying nanoparticle release kinetics, permitting sequential release [96]. A sustained infusion of cytokine nanoparticles over time could prolong a state of differentiation among seeded cells, until nascent tissue develops sufficiently to autonomously maintain a chondrocyte population.

Nanomaterials can thus influence and improve scaffold design in a variety of ways. Several techniques for scaffold nano-modification exist, but many are yet to be implemented for cartilage tissue engineering.

3.4. Limitations to Clinical Translation of Nanomaterial Scaffolds

Examining the literature on this topic has yielded no studies that have progressed beyond in vitro and in vivo experimentation. Most constructs are reported as developing “hyaline-like” neocartilage, as opposed to durable, clinically useful tissue, which exhibits the zonal arrangement of native cartilage. Eventual loss of chondrocyte phenotype in seeded cells is a significant issue even in conventional approaches that do not use nanomaterials, likely contributing to suboptimal research outcomes. Further work in stem cell and material science is required to establish the optimal conditions for reproducible, high quality Tissue Engineering, before the use of nanomaterial scaffolds can move from bench to operating theatre. Considering that this is a relatively new area of research, there is a lack of robust preclinical evidence regarding the toxicity of nanomaterials. The optimal approach remains unclear. A comparison of the regenerative and replacement approaches to treating damaged cartilage has not determined one to be more advantageous than the other, and a professional consensus is not imminent.

A further limitation is that there is insufficient collaboration between clinicians and tissue engineering researchers. Few clinicians are directly involved with lab-based research, and key issues in the practical application of tissue engineering constructs tend to be addressed late in the development of these technologies. With tissue engineering constructs, the logistics of surgical implantation influence the choice of scaffold material just as much as the need to optimize cell behaviour and tissue growth. Preoperatively, factors such as sterilization and stability must be considered. Intraoperatively, the scaffold would have to fit different injury morphologies, and the material would need to be amenable to modification. An alternative option would be the use of nanomaterials compatible with 3D printers; computer-aided design could be used to configure patient-specific scaffolds. Systems for the printing of scaffolds in sterile conditions have been described in the literature [97]. Post-operatively, the effect of selected nanomaterials on haemorrhage, thromboembolism, wound healing, immunogenicity and oncogenic potential are also essential to explore. The academic paradigm places emphasis on optimizing the basic science of tissue engineering, wherein scaffold development is focused on directing cell behaviour, rather than tailoring product design towards a specific clinical application. Including surgeons early on in the development process would streamline the development of scaffolds that address both cellular and clinical demands.

Beyond the laboratory, complex legal, economic and regulatory issues hinder progress towards clinical translation. Despite their considerable potential to improve affected individuals’ quality of life, funding and industrial support for the development of cartilage tissue engineering constructs is difficult to obtain, as the target diseases are rarely life threatening, and have not adequately impacted the psyche of policy makers. Funding is further limited by industry reluctance to support novel therapies until sufficient evidence of preclinical success is demonstrated. This is itself restricted by a lack of fiscal support, in reciprocal fashion. With the rapid evolution of the field of Tissue Engineering, it is becoming increasingly difficult to reach a consensus regarding its general definition. The concepts of nanotechnology and nanomaterials remain poorly understood outside specialist circles, adversely impacting commercial viability and funding. Consequentially, regulatory agencies have difficulty providing comprehensive guidelines for Tissue Engineering systems, further limiting potential for commercialization and future clinical use. Tissue engineering constructs currently fall under the umbrella of Advanced-therapy Medicinal Product (ATMP) regulation, as defined by the European Medicines Agency. Gaining approval for an ATMP requires completion of large-animal model trials, in addition to randomized controlled clinical trials, exerting a substantial financial burden on researchers. While it could be argued that the demands of ATMP regulation are essential to prevent the clinical implementation of unsafe products, in its current iteration, the complexity of the regulatory pathway limits industrial interest and investment. In addition, agencies are involved late in the development process, and when barriers to translation from their perspective are communicated to researchers, this can further delay the translation pathway while corrections are made. Under current regulatory legal frameworks, novel constructs featuring nanotechnology may face even greater translational limitations owing to their arcane nature. A new, internationally standardized regulatory framework may be necessary to address these issues. Overall, a collaborative effort towards better communication between researchers, healthcare professionals and regulatory agencies is essential to overcome these obstacles.

CONCLUSION

There exist a wide variety of applications for Nanomaterials in cartilage tissue repair, from both replacement and regenerative paradigms. The integration of nanotechnology into regenerative medicine has the potential to overcome several disadvantages of current therapies. However, research into this technology remains in its infancy, and a robust understanding of nanoscale phenomena within the human body remains to be established. Further development of Nanomaterials for cartilage reconstruction must focus not only on improving the quality of implant-host integration, but also overcoming roadblocks against clinical translation. In the future, these technologies may become commonplace in clinical practice, but several steps remain before this goal can be reached.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

- ACI

= Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation

- ATMP

= Advanced-therapy Medicinal Product

- bFGF

= Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor

- CS

= Chondroitin Sulphate

- DNA

= Deoxyribonucleic Acid

- ECM

= Extracellular Matrix

- HA

= Hydroxyapatite

- IGF

= Insulin-like Growth Factor

- MSCs

= Multipotent Stromal Cells

- PCL

= Poly-L-lactide-caprolactone

- PEG

= Polyethylene glycol

- PGA

= Poly-glycolic acid

- PLA

= Poly-L-lactic acid

- PLGA

= Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)

- POSS-PCU

= Poly-oligomeric-silsesquioxane nanoparticles incorporated into poly-carbonate-urea

- PRP

= Platelet rich plasma

- PVA-MA

= Polyvinylalcohol-methacrylate

- RGD

= Arginylglycylaspartic acid

- ROS

= Reactive Oxygen Species

- TGF

= Transforming Growth Factor

- UHMWPE

= Ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Drake R.L., Vogl W., Mitchell A.W., Gray H., Gray H. Gray’s anatomy for students. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kessler M.W., Grande D.A. Tissue engineering and cartilage. Organogenesis. 2008;4(1):28–32. doi: 10.4161/org.6116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lawrence R.C., Felson D.T., Helmick C.G., Arnold L.M., Choi H., Deyo R.A., Gabriel S., Hirsch R., Hochberg M.C., Hunder G.G., Jordan J.M., Katz J.N., Kremers H.M., Wolfe F., National Arthritis Data Workgroup Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part II. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(1):26–35. doi: 10.1002/art.23176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Litwic A., Edwards M.H., Dennison E.M., Cooper C. Epidemiology and burden of osteoarthritis. Br. Med. Bull. 2013;105:185–199. doi: 10.1093/bmb/lds038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hootman J.M., Helmick C.G. Projections of US prevalence of arthritis and associated activity limitations. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(1):226–229. doi: 10.1002/art.21562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perruccio A.V., Power J.D., Badley E.M. Revisiting arthritis prevalence projectionsits more than just the aging of the population. J. Rheumatol. 2006;33(9):1856–1862. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hunter D.J., Schofield D., Callander E. The individual and socioeconomic impact of osteoarthritis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2014;10(7):437–441. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2014.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharma K., Goswami S.C., Baruah D.K. Auricular trauma and its management. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;58(3):232–234. doi: 10.1007/BF03050826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Avila J., Bosch A., Aristizábal S., Frías Z., Marcial V. Carcinoma of the pinna. Cancer. 1977;40(6):2891–2895. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197712)40:6<2891::AID-CNCR2820400619>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luquetti D.V., Heike C.L., Hing A.V., Cunningham M.L., Cox T.C. Microtia: epidemiology and genetics. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2012;158A(1):124–139. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.34352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sarper A., Ayten A., Eser I., Ozbudak O., Demircan A. Tracheal stenosis aftertracheostomy or intubation: review with special regard to cause and management. Tex. Heart Inst. J. 2005;32(2):154–158. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bert J.M. Abandoning microfracture of the knee: has the time come? Arthroscopy. 2015;31(3):501–505. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2014.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eldracher M., Orth P., Cucchiarini M., Pape D., Madry H. Small subchondral drill holes improve marrow stimulation of articular cartilage defects. Am. J. Sports Med. 2014;42(11):2741–2750. doi: 10.1177/0363546514547029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kreuz P.C., Steinwachs M.R., Erggelet C., Krause S.J., Konrad G., Uhl M., Südkamp N. Results after microfracture of full-thickness chondral defects in different compartments in the knee. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006;14(11):1119–1125. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goyal D., Keyhani S., Lee E.H., Hui J.H. Evidence-based status of microfracture technique: a systematic review of level I and II studies. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(9):1579–1588. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2013.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Magnussen R.A., Dunn W.R., Carey J.L., Spindler K.P. Treatment of focal articular cartilage defects in the knee: a systematic review. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2008;466(4):952–962. doi: 10.1007/s11999-007-0097-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arthritis_Research UK. Osteoarthritis in General Practice. Data and Perspectives; 2013. Available from: http://www.arthritisresearchuk.org/ policy-and-public-affairs/reports-and-resources/reports.aspx . [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mueller-Rath R., Kleffner B., Andereya S., Mumme T., Wirtz D.C. Measures for reducing ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene wear in total knee replacement: a simulator study. Biomed. Tech. (Berl.) 2007;52(4):295–300. doi: 10.1515/BMT.2007.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ingham E., Fisher J. Biological reactions to wear debris in total joint replacement. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. H. 2000;214(1):21–37. doi: 10.1243/0954411001535219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mohammadi S., Ghourchian S., Izadi F., Daneshi A., Ahmadi A. Porous high-density polyethylene in facial reconstruction and revision rhinoplasty: a prospective cohort study. Head Face Med. 2012;8:17. doi: 10.1186/1746-160X-8-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Romo T., III, Sclafani A.P., Jacono A.A. Nasal reconstruction using porous polyethylene implants. Facial Plast. Surg. 2000;16(1):55–61. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-7326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nayyer L., Birchall M., Seifalian A.M., Jell G. Design and development of nanocomposite scaffolds for auricular reconstruction. Nanomedicine (Lond.) 2014;10(1):235–246. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2013.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chae MP, Rozen WM, McMenamin PG, Findlay MW, Spychal RT, Hunter-Smith DJ. Emerging applications of bedside 3D printing in plastic surgery. Front. Surg. 2015;2:25. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2015.00025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoberg M., Konrads C., Engelien J., Oschmann D., Holder M., Walcher M., Steinert A. Similar outcomes between two-stage revisions for infection and aseptic hip revisions. Int. Orthop. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s00264-015-2850-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Romanò C.L., Romanò D., Logoluso N., Meani E. Septic versus aseptic hip revision: how different? J. Orthop. Traumatol. 2010;11(3):167–174. doi: 10.1007/s10195-010-0106-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cenzi R., Farina A., Zuccarino L., Carinci F. Clinical outcome of 285 Medpor grafts used for craniofacial reconstruction. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2005;16(4):526–530. doi: 10.1097/01.scs.0000168761.46700.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McEwen H.M., Barnett P.I., Bell C.J., Farrar R., Auger D.D., Stone M.H., Fisher J. The influence of design, materials and kinematics on the in vitro wear of total knee replacements. J. Biomech. 2005;38(2):357–365. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ryd L. Micromotion in knee arthroplasty. A roentgen stereophotogrammetric analysis of tibial component fixation. Acta Orthop. Scand. Suppl. 1986;220:1–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Daley B., Doherty A.T., Fairman B., Case C.P. Wear debris from hip or knee replacements causes chromosomal damage in human cells in tissue culture. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 2004;86(4):598–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones J.R. Observing cell response to biomaterials. Mater. Today. 2006;9(12):34–43. doi: 10.1016/S1369-7021(06)71741-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taubenberger A.V., Woodruff M.A., Bai H., Muller D.J., Hutmacher D.W. The effect of unlocking RGD-motifs in collagen I on pre-osteoblast adhesion and differentiation. Biomaterials. 2010;31(10):2827–2835. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.12.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Penny J.O., Ding M., Varmarken J.E., Ovesen O., Overgaard S. Early micromovement of the Articular Surface Replacement (ASR) femoral component: two-year radiostereometry results. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 2012;94(10):1344–1350. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.94B10.29030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dobratz E.J., Kim S.W., Voglewede A., Park S.S. Injectable cartilage: using alginate and human chondrocytes. Arch. Facial Plast. Surg. 2009;11(1):40–47. doi: 10.1001/archfacial.2008.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Homicz M.R., Chia S.H., Schumacher B.L., Masuda K., Thonar E.J., Sah R.L., Watson D. Human septal chondrocyte redifferentiation in alginate, polyglycolic acid scaffold, and monolayer culture. Laryngoscope. 2003;113(1):25–32. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200301000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang W.D., Chen S.J., Mao T.Q., Chen F.L., Lei D.L., Tao K., Tang L.H., Xiao M.G. A study of injectable tissue-engineered autologous cartilage. Chin. J. Dent. Res. 2000;3(4):10–15. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baek C.H., Ko Y.J. Characteristics of tissue-engineered cartilage on macroporous biodegradable PLGA scaffold. Laryngoscope. 2006;116(10):1829–1834. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000233521.49393.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qi Y., Du Y., Li W., Dai X., Zhao T., Yan W. Cartilage repair using mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) sheet and MSCs-loaded bilayer PLGA scaffold in a rabbit model. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2014;22(6):1424–1433. doi: 10.1007/s00167-012-2256-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moshaverinia A., Xu X., Chen C., Akiyama K., Snead M.L., Shi S. Dental mesenchymal stem cells encapsulated in an alginate hydrogel co-delivery microencapsulation system for cartilage regeneration. Acta Biomater. 2013;9(12):9343–9350. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Han S.H., Kim Y.H., Park M.S., Kim I.A., Shin J.W., Yang W.I., Jee K.S., Park K.D., Ryu G.H., Lee J.W. Histological and biomechanical properties of regenerated articular cartilage using chondrogenic bone marrow stromal cells with a PLGA scaffold in vivo. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 2008;87(4):850–861. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pettersson S., Wetterö J., Tengvall P., Kratz G. Human articular chondrocytes on macroporous gelatin microcarriers form structurally stable constructs with blood-derived biological glues in vitro. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2009;3(6):450–460. doi: 10.1002/term.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Akeda K., An H.S., Okuma M., Attawia M., Miyamoto K., Thonar E.J., Lenz M.E., Sah R.L., Masuda K. Platelet-rich plasma stimulates porcine articular chondrocyte proliferation and matrix biosynthesis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006;14(12):1272–1280. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mishra A., Tummala P., King A., Lee B., Kraus M., Tse V., Jacobs C.R. Buffered platelet-rich plasma enhances mesenchymal stem cell proliferation and chondrogenic differentiation. Tissue Eng. Part C Methods. 2009;15(3):431–435. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2008.0534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang S., Deng T., Wang Y., Deng Z., He L., Liu S., Yang J., Jin Y. Multifunctional implantable particles for skin tissue regeneration: preparation, characterization, in vitro and in vivo studies. Acta Biomater. 2008;4(4):1057–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2008.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shekaran A., Garcia A.J. Nanoscale engineering of extracellular matrix-mimetic bioadhesive surfaces and implants for tissue engineering. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2011;1810(3):350–360. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maheshwari G., Brown G., Lauffenburger D.A., Wells A., Griffith L.G. Cell adhesion and motility depend on nanoscale RGD clustering. J. Cell Sci. 2000;113(Pt 10):1677–1686. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.10.1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Langer R., Vacanti J.P. Tissue engineering. Science. 1993;260(5110):920–926. doi: 10.1126/science.8493529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hamilton D.W., Riehle M.O., Monaghan W., Curtis A.S. Chondrocyte aggregation on micrometric surface topography: a time-lapse study. Tissue Eng. 2006;12(1):189–199. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lin YC, Tambe DT, Park CY, Wasserman MR, Trepat X, Krishnan R, et al. Mechanosensing of substrate thickness. Phy. Rev E, Stat. Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2010;82(4 Pt 1):041918. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.82.041918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang N., Tytell J.D., Ingber D.E. Mechanotransduction at a distance: mechanically coupling the extracellular matrix with the nucleus. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009;10(1):75–82. doi: 10.1038/nrm2594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Park J.S., Chu J.S., Tsou A.D., Diop R., Tang Z., Wang A., Li S. The effect of matrix stiffness on the differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells in response to TGF-β. Biomaterials. 2011;32(16):3921–3930. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sanz-Ramos P., Mora G., Vicente-Pascual M., Ochoa I., Alcaine C., Moreno R., Doblaré M., Izal-Azcárate I. Response of sheep chondrocytes to changes in substrate stiffness from 2 to 20 Pa: effect of cell passaging. Connect. Tissue Res. 2013;54(3):159–166. doi: 10.3109/03008207.2012.762360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bettinger C.J., Langer R., Borenstein J.T. Engineering substrate micro- and nanotopography to control cell function. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48(30):5406–5415. doi: 10.1002/anie.200805179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu H., Webster T.J. Nanomedicine for implants: a review of studies and necessary experimental tools. Biomaterials. 2007;28(2):354–369. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kumar Khanna V. Targeted delivery of nanomedicines. ISRN Pharmacol. 2012;2012:571394. doi: 10.5402/2012/571394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ma Y., Zheng Y., Wei G., Song W., Hu T., Yang H., Xue R. Processing, structure, and properties of multiwalled carbon nanotube/poly(hydroxybutyrate-co-valerate) biopolymer nanocomposites. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2012;125(S1):E620–E9. doi: 10.1002/app.35650. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.De Leo F., Magistrato A., Bonifazi D. Interfacing proteins with graphitic nanomaterials: from spontaneous attraction to tailored assemblies. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015;44(19):6916–6953. doi: 10.1039/C5CS00190K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fiedler J., Ozdemir B., Bartholomä J., Plettl A., Brenner R.E., Ziemann P. The effect of substrate surface nanotopography on the behavior of multipotnent mesenchymal stromal cells and osteoblasts. Biomaterials. 2013;34(35):8851–8859. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shimaya M., Muneta T., Ichinose S., Tsuji K., Sekiya I. Magnesium enhances adherence and cartilage formation of synovial mesenchymal stem cells through integrins. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010;18(10):1300–1309. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Samardak A., Anisimova M., Samardak A., Ognev A. Fabrication of high-resolution nanostructures of complex geometry by the single-spot nanolithography method. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2015;6:976–986. doi: 10.3762/bjnano.6.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guo Z., Xu J., Ding S., Li H., Zhou C., Li L. In vitro evaluation of random and aligned polycaprolactone/gelatin fibers via electrospinning for bone tissue engineering. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2015;26(15):989–1001. doi: 10.1080/09205063.2015.1065598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.González-Henríquez C.M., del C Pizarro G., Sarabia-Vallejos M.A., Terraza C.A. Thin and ordered hydrogel films deposited through electrospinning technique; a simple and efficient support for organic bilayers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2015;1848(10 Pt A):2126–2137. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2015.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lentino J.R. Prosthetic joint infections: bane of orthopedists, challenge for infectious disease specialists. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2003;36(9):1157–1161. doi: 10.1086/374554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Costerton J.W., Montanaro L., Arciola C.R. Biofilm in implant infections: its production and regulation. Int. J. Artif. Organs. 2005;28(11):1062–1068. doi: 10.1177/039139880502801103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Singh A.V., Vyas V., Patil R., Sharma V., Scopelliti P.E., Bongiorno G., Podestà A., Lenardi C., Gade W.N., Milani P. Quantitative characterization of the influence of the nanoscale morphology of nanostructured surfaces on bacterial adhesion and biofilm formation. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e25029. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mitik-Dineva N., Wang J., Mocanasu R.C., Stoddart P.R., Crawford R.J., Ivanova E.P. Impact of nano-topography on bacterial attachment. Biotechnol. J. 2008;3(4):536–544. doi: 10.1002/biot.200700244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lemire J.A., Harrison J.J., Turner R.J. Antimicrobial activity of metals: mechanisms, molecular targets and applications. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2013;11(6):371–384. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chaloupka K., Malam Y., Seifalian A.M. Nanosilver as a new generation of nanoproduct in biomedical applications. Trends Biotechnol. 2010;28(11):580–588. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zarkadas G.M., Stergiou A., Papanastasiou G. Influence of citric acid on the silver electrodeposition from aqueous AgNO3 solutions. Electrochim. Acta. 2005;50(25–26):5022–5031. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2005.02.081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.De Giglio E., Cafagna D., Cometa S., Allegretta A., Pedico A., Giannossa L.C., Sabbatini L., Mattioli-Belmonte M., Iatta R. An innovative, easily fabricated, silver nanoparticle-based titanium implant coating: development and analytical characterization. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2013;405(2-3):805–816. doi: 10.1007/s00216-012-6293-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fielding G.A., Roy M., Bandyopadhyay A., Bose S. Antibacterial and biological characteristics of silver containing and strontium doped plasma sprayed hydroxyapatite coatings. Acta Biomater. 2012;8(8):3144–3152. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chen W., Liu Y., Courtney H.S., Bettenga M., Agrawal C.M., Bumgardner J.D., Ong J.L. In vitro anti-bacterial and biological properties of magnetron co-sputtered silver-containing hydroxyapatite coating. Biomaterials. 2006;27(32):5512–5517. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Williams D. Essential Biomaterials Science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Biggs M.J., Richards R.G., Gadegaard N., Wilkinson C.D., Dalby M.J. The effects of nanoscale pits on primary human osteoblast adhesion formation and cellular spreading. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2007;18(2):399–404. doi: 10.1007/s10856-006-0705-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Torrecillas R., Moya J.S., Díaz L.A., Bartolomé J.F., Fernández A., Lopez-Esteban S. Nanotechnology in joint replacement. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2009;1(5):540–552. doi: 10.1002/wnan.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Liu M., Ishida Y., Ebina Y., Sasaki T., Hikima T., Takata M., Aida T. An anisotropic hydrogel with electrostatic repulsion between cofacially aligned nanosheets. Nature. 2015;517(7532):68–72. doi: 10.1038/nature14060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Xin X., Hussain M., Mao J.J. Continuing differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells and induced chondrogenic and osteogenic lineages in electrospun PLGA nanofiber scaffold. Biomaterials. 2007;28(2):316–325. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.08.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kumbar S.G., James R., Nukavarapu S.P., Laurencin C.T. Electrospun nanofiber scaffolds: engineering soft tissues. Biomed. Mater. 2008;3(3):034002. doi: 10.1088/1748-6041/3/3/034002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Coburn J., Gibson M., Bandalini P.A., Laird C., Mao H-Q., Moroni L., Seliktar D., Elisseeff J. Biomimetics of the extracellular matrix: An integrated three-dimensional fiber-hydrogel composite for cartilage tissue engineering. Smart Struct. Syst. 2011;7(3):213–222. doi: 10.12989/sss.2011.7.3.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Coburn J.M., Gibson M., Monagle S., Patterson Z., Elisseeff J.H. Bioinspired nanofibers support chondrogenesis for articular cartilage repair. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109(25):10012–10017. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121605109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mohsenkhani S., Jahanshahi M., Rahimpour A. Cross-linked κ-carrageenan polymer/zinc nanoporous composite matrix for expanded bed application: Fabrication and hydrodynamic characterization. J. Chromatogr. A. 2015;1408:178–186. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2015.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mubeena S., Chatterji A. Hierarchical self-assembly: Self-organized nanostructures in a nematically ordered matrix of self-assembled polymeric chains. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 2015;91(3):032602. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.91.032602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chen D.W., Liu S.J. Nanofibers used for delivery of antimicrobial agents. Nanomedicine (Lond.) 2015;10(12):1959–1971. doi: 10.2217/nnm.15.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.He L., Liu B., Xipeng G., Xie G., Liao S., Quan D., Cai D., Lu J., Ramakrishna S. Microstructure and properties of nano-fibrous PCL-b-PLLA scaffolds for cartilage tissue engineering. Eur. Cell. Mater. 2009;18:63–74. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v018a06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Xue D., Zheng Q., Zong C., Li Q., Li H., Qian S., Zhang B., Yu L., Pan Z. Osteochondral repair using porous poly(lactide-co-glycolide)/nano-hydroxyapatite hybrid scaffolds with undifferentiated mesenchymal stem cells in a rat model. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 2010;94(1):259–270. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Teoh G.Z., Crowley C., Birchall M.A., Seifalian A.M. Development of resorbable nanocomposite tracheal and bronchial scaffolds for paediatric applications. Br. J. Surg. 2015;102(2):e140–e150. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kay S., Thapa A., Haberstroh K.M., Webster T.J. Nanostructured polymer/nanophase ceramic composites enhance osteoblast and chondrocyte adhesion. Tissue Eng. 2002;8(5):753–761. doi: 10.1089/10763270260424114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Oseni AO, Butler PE, Seifalian AM. The application of POSS nanostructures in cartilage tissue engineering: the chondrocyte response to nanoscale geometry. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2013;9(11):E27–38. doi: 10.1002/term.1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Guasti L., Vagaska B., Bulstrode N.W., Seifalian A.M., Ferretti P. Chondrogenic differentiation of adipose tissue-derived stem cells within nanocaged POSS-PCU scaffolds: a new tool for nanomedicine. Nanomedicine (Lond.) 2014;10(2):279–289. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2013.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ruoslahti E. RGD and other recognition sequences for integrins. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 1996;12:697–715. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cavalcanti-Adam E.A., Micoulet A., Blümmel J., Auernheimer J., Kessler H., Spatz J.P. Lateral spacing of integrin ligands influences cell spreading and focal adhesion assembly. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2006;85(3-4):219–224. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2005.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Cavalcanti-Adam E.A., Volberg T., Micoulet A., Kessler H., Geiger B., Spatz J.P. Cell spreading and focal adhesion dynamics are regulated by spacing of integrin ligands. Biophys. J. 2007;92(8):2964–2974. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.089730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Goldring M.B. Chondrogenesis, chondrocyte differentiation, and articular cartilage metabolism in health and osteoarthritis. Ther. Adv. Musculoskelet. Dis. 2012;4(4):269–285. doi: 10.1177/1759720X12448454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Fan H., Zhang C., Li J., Bi L., Qin L., Wu H., Hu Y. Gelatin microspheres containing TGF-beta3 enhance the chondrogenesis of mesenchymal stem cells in modified pellet culture. Biomacromolecules. 2008;9(3):927–934. doi: 10.1021/bm7013203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lee J.E., Kim K.E., Kwon I.C., Ahn H.J., Lee S.H., Cho H., Kim H.J., Seong S.C., Lee M.C. Effects of the controlled-released TGF-beta 1 from chitosan microspheres on chondrocytes cultured in a collagen/chitosan/glycosaminoglycan scaffold. Biomaterials. 2004;25(18):4163–4173. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.10.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zhu X.H., Tabata Y., Wang C.H., Tong Y.W. Delivery of basic fibroblast growth factor from gelatin microsphere scaffold for the growth of human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Tissue Eng. Part A. 2008;14(12):1939–1947. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2007.0346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Yamamoto M., Ikada Y., Tabata Y. Controlled release of growth factors based on biodegradation of gelatin hydrogel. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2001;12(1):77–88. doi: 10.1163/156856201744461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hockaday L.A., Kang K.H., Colangelo N.W., Cheung P.Y., Duan B., Malone E., Wu J., Girardi L.N., Bonassar L.J., Lipson H., Chu C.C., Butcher J.T. Rapid 3D printing of anatomically accurate and mechanically heterogeneous aortic valve hydrogel scaffolds. Biofabrication. 2012;4(3):035005. doi: 10.1088/1758-5082/4/3/035005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]