Abstract

Background

Clinical trials have, so far, failed to establish clear beneficial outcomes of recruitment maneuvers (RMs) on patient mortality in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and the effects of RMs on the cardiovascular system remain poorly understood.

Methods

A computational model with highly integrated pulmonary and cardiovascular systems was configured to replicate static and dynamic cardio-pulmonary data from clinical trials. Recruitment maneuvers (RMs) were executed in 23 individual in-silico patients with varying levels of ARDS severity and initial cardiac output. Multiple clinical variables were recorded and analyzed, including arterial oxygenation, cardiac output, peripheral oxygen delivery and alveolar strain.

Results

The maximal recruitment strategy (MRS) maneuver, which implements gradual increments of positive end expiratory pressure (PEEP) followed by PEEP titration, produced improvements in PF ratio, carbon dioxide elimination and dynamic strain in all 23 in-silico patients considered. Reduced cardiac output in the moderate and mild in silico ARDS patients produced significant drops in oxygen delivery during the RM (average decrease of 423 ml min−1 and 526 ml min−1, respectively). In the in-silico patients with severe ARDS, however, significantly improved gas-exchange led to an average increase of 89 ml min−1 in oxygen delivery during the RM, despite a simultaneous fall in cardiac output of more than 3 l min−1 on average. Post RM increases in oxygen delivery were observed only for the in silico patients with severe ARDS. In patients with high baseline cardiac outputs (>6.5 l min−1), oxygen delivery never fell below 700 ml min−1.

Conclusions

Our results support the hypothesis that patients with severe ARDS and significant numbers of alveolar units available for recruitment may benefit more from RMs. Our results also indicate that a higher than normal initial cardiac output may provide protection against the potentially negative effects of high intrathoracic pressures associated with RMs on cardiac function. Results from in silico patients with mild or moderate ARDS suggest that the detrimental effects of RMs on cardiac output can potentially outweigh the positive effects of alveolar recruitment on oxygenation, resulting in overall reductions in tissue oxygen delivery.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12890-017-0369-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Acute respiratory distress syndrome, Recruitment maneuvers, Positive end expiratory pressure, Cardiac output, Computational modelling, Oxygen delivery, Carbon dioxide clearance, Strain, Mechanical ventilation

Background

Recruitment maneuvers (RMs) are used as a strategy to improve oxygenation and reduce the risk of atelectrauma in ARDS patients by re-opening and stabilising collapsed lung regions [1]. Several RMs have so far been proposed, including sustained inflations with continuous positive airway pressure of 35–50 cm H20 for 20–40 s [2], incremental peak inspiratory pressures [3], lower tidal volumes (with sighs), intermittent sighs [4], stepwise increments in positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) [5], and slow increases of inspiratory pressure to 40 cm H2O [6]. Despite numerous studies, there is still little conclusive evidence that RMs improve overall outcomes (including mortality) in critically ill patients [4, 7, 8]. The consensus is that RMs should be considered on an individual basis, but the optimal pressure, duration and frequency of RMs remain to be determined, and few guidelines are available to enable effective patient stratification.

Increased intrathoracic pressures (PIT) produced by RMs significantly affect left ventricular (LV) preload, right ventricular (RV) afterload and biventricular compliance [9]. Right ventricular preload is also affected by the impairment of the right atrium and by increased resistance to systemic venous return. Increase in PIT reduces the pressure gradient between the systemic venous pressure and the RV diastolic pressure, reducing venous return, decreasing RV filling and consequently decreasing stroke volume (SV) and decreasing inflow to the left ventricle [10]. This passive relationship between RV and LV is compounded by the direct effects of raised PIT [9] on the ventricular walls (splinting) as well as the potential for intraventricular septum shift (ventricular interdependence) [11]. The consequences of these complex relationships affecting RV/LV function and heart-lung interaction are difficult to quantify or investigate in the clinical environment. Reliably evaluating the relative effectiveness of different RMs in clinical studies is also extremely challenging, since it is difficult to isolate the effects of ventilatory strategies, and because different RMs cannot be applied to the same patient simultaneously.

In contrast, in silico models of individualised patient and disease pathology allow different RMs to be applied to the same patient with exactly the same baseline pathophysiology, in order to understand their mode of action and quantitatively compare their effectiveness in different scenarios. Previous computational modelling studies have shown the potential of this approach to add significantly to our understanding of cardiopulmonary pathophysiology [12, 13] and the mechanisms associated with alveolar recruitment [13–16].

Methods

Computational model

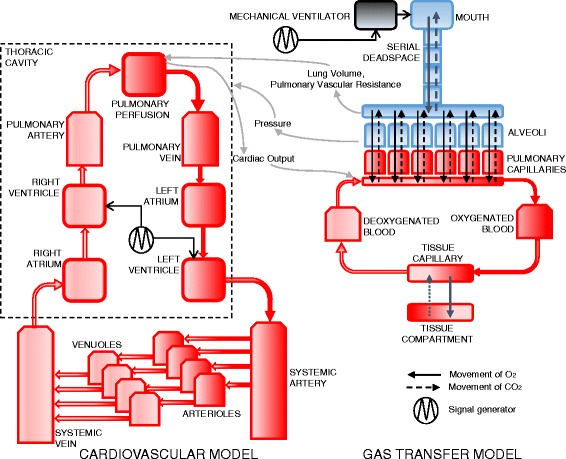

Our study employs a highly integrated computer simulation model of the pulmonary and cardiovascular systems that has recently been developed by our group [17–19]. The model architecture and its main components are depicted in Fig. 1. The pulmonary model includes 100 independently configured alveolar compartments, multi-compartmental gas-exchange, viscoelastic compliance behaviour, interdependent blood-gas solubilities and haemoglobin behaviour and heterogeneous distributions of pulmonary ventilation and perfusion. The ability of this model to accurately represent multiple aspects of pulmonary pathophysiology have been validated in a number of previous studies [17, 20–22]. This model was integrated with a dynamic, contractile cardiovascular model with 19-compartments, pulsatile blood flow and ventilation-affected, trans-alveolar blood-flow. The cardiac section of the model consists of two contractile ventricles, with atria modelled as non-contractile, low-resistance, high-compliance compartments.

Fig. 1.

Architecture of the integrated cardiopulmonary model

Cardiopulmonary interactions are modelled in a number of ways. Ventricular contractility is modelled as a truncated sine-wave that varies ventricular elastance over time [23]. Intrapulmonary pressure is transmitted variably across ventricular walls (depending on ventricular stiffness) such that lung inflation “splints” the ventricles; transmitting intrathoracic pressure to the intraventricular and intravascular spaces. Trans-alveolar blood flow is governed by pulmonary artery pressure, and by independent trans-alveolar vascular resistance; this resistance is affected dynamically in each alveolar compartment by alveolar volume (causing longitudinal stretch) and pressure (causing axial compression).

The mathematical principles and equations underpinning the model are explained in detail in the Additional file 1.

Measurements

To observe the hemodynamic effects of interest, the following values were recorded: cardiac output (CO), right ventricle end diastolic volume (RVEDV), right ventricle end systolic volume (RVESV), mean arterial pressure (MAP), and mean pulmonary artery pressure (MPAP). Other parameters recorded from the model included: arterial oxygen tension (PaO2), arterial carbon dioxide tension (PaCO2), arterial pH (pHa), arterial and mixed venous oxygen saturation (SaO2 and SvO2, respectively), static lung compliance (Cstat), plateau pressure (Pplat), volume of individual alveolar compartments at end of inspiration and end of expiration (Valv_insp and Valv_exp, respectively), and pressure of individual compartments at end of inspiration and end of expiration (Palv_insp and Palv_exp, respectively). Recruitment was calculated as the fraction of alveoli receiving non-zero ventilation. The strain on the lung is given as both dynamic and static [24]. The dynamic strain is calculated as ∆V/Vfrc, where Vfrc is Valv_exp at PEEP = 0 and ∆V = Valv_insp-Valv_exp. Static strain is calculated as Valv_exp/Vfrc. All parameters were recorded every 10 milliseconds and the plots have been generated with mean values taken over a duration of 1 s.

Patients datasets

Two ARDS patient datasets were selected from the published literature, based on their inclusion of hemodynamic responses to changes in mechanical ventilation (see Table 1 (for first dataset) and Table 2 (for the second dataset).

Table 1.

Results of fitting the model to ARDS patient data of PaO2 and PaCO2

| Moderate ARDS, High CO [25] | Moderate ARDS, Normal CO [26] | Severe ARDS, High CO [27] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters obtained from data | CO (l min−1) | 8 | 4.09 | 7.3 | |||

| FIO2 | 0.5 | 0.45 | 1 | ||||

| Vt (ml kg−1) | 12 | 10 | 10 | ||||

| PEEP (cm H2O) | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Parameters determined by optimizationa | VR (b min−1) | 12 | 10 | 10 | |||

| Duty Cycle | 0.33 | 0.35 | 0.46 | ||||

| RQ | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.7 | ||||

| VO2 (ml min−1) | 307 | 303 | 306 | ||||

| Hb (g dl−1) | 9.9 | 14.5 | 10.5 | ||||

| Data | Model | Data | Model | Data | Model | ||

| Results of fitting the model to the data | PaO2 (kpa) | 10.6 | 11.2 | 10 | 10.8 | 6.6 | 7.5 |

| PaCO2 (kpa) | 5 | 4.4 | 5.3 | 5.2 | 3.7 | 4.3 | |

| Other results | PvO2 (kpa) | NA | 4.6 | NA | 4.4 | NA | 4.1 |

| Shunt Fraction (%) | NA | 22 | NA | 16 | NA | 44 | |

List of Abbreviations CO cardiac output, FiO 2 fraction of O2 in inspired gas, Vt tidal volume, VR ventilator rate, PEEP positive end expiratory pressure, IE inspiratory to expiratory ratio, RQ respiratory quotient, VO 2 oxygen consumption, TOP threshold opening pressure, S alveolar stiffness factor, Pext extrinsic pressure, Hb hemoglobin in blood, PaO 2 arterial oxygen tension, PaCO 2 arterial carbon dioxide tension, PvO 2 mixed venous oxygen tension, shunt fraction

aOptimization methodology and parameter ranges given in Additional file 1

Table 2.

Results of fitting the model to 20 ARDS patient data of PaO2, PaCO2 and Cstat at baseline

| All Patients | Severe ARDS | Moderate ARDS | Mild ARDS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 20 | 11 | 6 | 3 | |||||

| Vt (ml kg−1) | 6 | ||||||||

| VR (b min−1) | 12 | ||||||||

| PEEP (cm H2O) | 10 | ||||||||

| Ventilation mode | Volume controlled | ||||||||

| FIO2 | 1 | ||||||||

| HR (bpm) | 100 | ||||||||

| mean | sd | mean | sd | mean | sd | mean | sd | ||

| Parameters determined by optimizationa | CI (l min−1 m−2) | 5.3 | 0.5 | 5.0 | 0.4 | 5.6 | 0.5 | 6.0 | 0.1 |

| RQ | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 0.1 | |

| VO2 (ml min−1) | 304.4 | 6.3 | 305.8 | 3.8 | 303.8 | 8.0 | 300.3 | 10.6 | |

| Duty Cycle | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.0 | |

| Hb (g l−1) | 110.5 | 39.5 | 92.5 | 32.6 | 115.8 | 33.9 | 165.7 | 13.5 | |

| Results of fitting the model to the data | PaO2 (mm Hg) | 120.9 | 73.2 | 68.6 | 10.6 | 149.5 | 36.1 | 255.3 | 49.7 |

| Cstat (ml/cm H2O) | 25.0 | 6.4 | 22.0 | 4.5 | 27.3 | 4.5 | 31.7 | 10.1 | |

| PaCO2 (mmHg) | 61.2 | 3.6 | 59.3 | 2.9 | 62.3 | 3.3 | 65.7 | 1.2 | |

| Other results | Shunt Fraction (%) | 37.6 | 12.3 | 46.5 | 5.0 | 30.8 | 5.5 | 18.7 | 11.7 |

| Pplat (cm H2O) | 27.4 | 4.1 | 29.4 | 4.1 | 25.3 | 2.1 | 24.0 | 4.4 | |

| TOP (cm H2O) | 21.6 | 2.4 | 22.3 | 2.8 | 21.0 | 2.0 | 20.0 | 0.0 | |

List of Abbreviations CI cardiac index, FiO 2 fraction of O2 in inspired gas, Vt tidal volume, VR ventilator rate, PEEP positive end expiratory pressure, IE inspiratory to expiratory ratio, RQ respiratory quotient, VO 2 oxygen consumption, TOP threshold opening pressure, S alveolar stiffness factor, Pext extrinsic pressure, Hb hemoglobin in blood, PaO 2 arterial oxygen tension, Cstat static compliance, PaCO 2 arterial carbon dioxide tension, PvO 2 mixed venous oxygen tension, TOP threshold opening pressures, Pplat plateau pressure

aOptimization methodology and parameter ranges given in Additional file 1

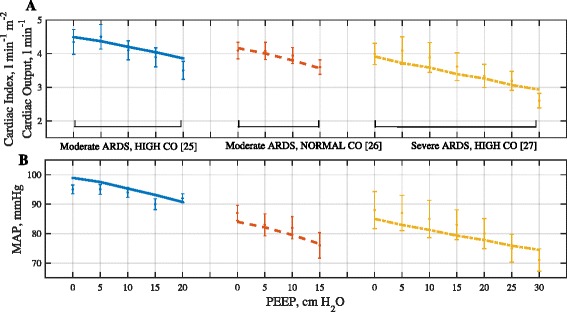

The first in silico dataset consisted of three individual in silico ARDS patients that could be stratified by ARDS severity and different baseline cardiac output levels (Table 1). The first patient, data from [25], had a PF ratio of 150 mmHg and CO of 8 l min−1 (i.e. moderate severity ARDS, with high CO) at PEEP = 0 cm H2O. The second patient, data from [26], had a PF ratio of 167 mmHg and CO of 4.09 l min−1 (i.e. moderate severity ARDS, with normal CO), while the third patient, data from [27], had a PF ratio of 50 mmHg and CO of 7.3 l min−1 (severe ARDS, with high CO). This dataset was used to determine the model’s lung configuration to yield responses of PaO2 and PaCO2 corresponding to the static data values. Following this, the cardiovascular model parameters were configured to changes in CO and MAP at different values of PEEP (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Results of fitting model outputs for hemodynamic variables to patient data. a Cardiac index (or Cardiac output for the case of Moderate ARDS, Normal CO) and b MAP. The lines represent the model results while the error bars depict the data. Three patients are: Moderate ARDS High CO (blue), Moderate ARDS Normal CO (red), Severe ARDS High CO (yellow)

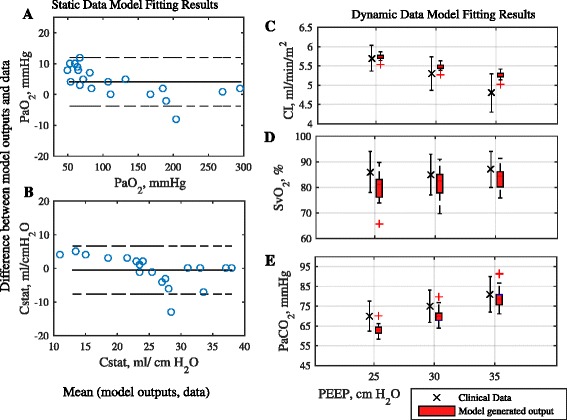

Table 2 lists the baseline characteristics of the second in silico dataset, comprising 20 patients with varying severity of ARDS, extracted from [5]. For each patient, the reported values of the ratio of PaO2 to fraction of oxygen in inhaled air (PF ratio) and the Cstat were used to fit lung configuration of the model at baseline settings of PEEP = 10 cm H2O and Pplat = 30 cm H2O (static data). The cardiovascular model parameters were then estimated to fit model responses to average values of CO, mixed venous oxygen saturation (SvO2) and PaCO2 at different PEEP levels (25, 30 and 35 cm H2O) (dynamic data) (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

a and b: Bland Altman plots of difference in model outputs against values listed in data for PaO2 and Cstat respectively, plotted against mean of the model output and the data. Solid line represents bias and dashed lines represent 95% limits of agreement. Box plots in c, d and e depict the distribution of model generated values at different PEEP levels for Cardiac index (CI), mixed venous oxygen saturation (SvO2) and arterial carbon dioxide tension (PaCO2). The errorbars correspond to the population distribution of data at corresponding PEEP values

As stated above, the model was configured to reproduce data corresponding to ARDS patients in two stages, to static data at a single value of PEEP and then to dynamic data at varying values of PEEP. In the first stage, a global optimization algorithm was used to search for a configuration of lung parameters consisting of: threshold opening pressure (TOP), alveolar stiffness (S), extrinsic pressure (Pext) and microbronchial (inlet) resistance (Ralv) for each alveolar compartment. Further objectives specified for the optimization were to keep average TOP to 20 cm H2O [28], and to keep Pplat below 30 cm H2O [29]. In the second stage of model matching, cardiovascular parameters in the model (e.g. compartmental elastances and blood volumes, arterial resistances, non-linear effects on pulmonary vascular resistance and intrathoracic ventricular splinting - see Additional file 1) were optimized to match observed changes in CO and MAP at different values of PEEP. All patients were assumed to have a weight of 70 kg and body surface area of 1.79 m2. Full details of how the model was matched to the patient data are provided in the Additional file 1.

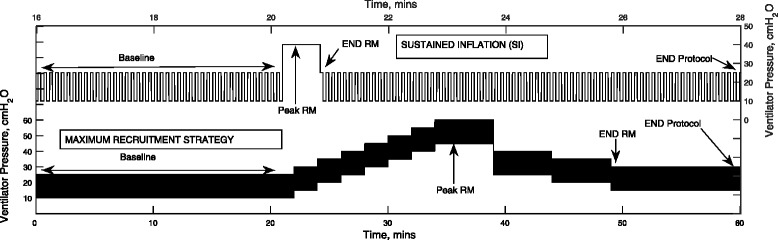

Recruitment maneuver protocols

RM protocols were executed by establishing a baseline steady-state condition for 20 min, executing the RM, and finally establishing a new post-RM steady-state. To establish the baseline condition, the simulated patients were subjected to identical PEEP (10 cm H2O) and identical inspiratory pressure (15 cm H2O above PEEP), as reported in [30]. Post RM, the inspiratory pressure is maintained at 15 cm H2O above PEEP. Throughout the protocols, only the ventilator pressure was altered. Two RMs from the published literature were implemented in the simulator, as detailed below and illustrated in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Ventilator pressure waveform for sustained inflation (SI) and maximal recruitment strategy (MRS)

Maximal recruitment strategy (MRS) [30]

The maneuver comprises of PEEP adjustment in pressure-controlled mode, with a fixed driving pressure of 15 cm H2O (above PEEP). During the recruitment phase, PEEP was increased from 10 cm H2O to a maximum of 45 cm H2O in steps of 5 cm H2O, with each step lasting 2 min. During the PEEP-titration phase, the PEEP is set to 25 cm H2O and then reduced by 5 cmH2O in steps to the end-maneuver PEEP, with each step lasting 5 min. The PEEP titration was stopped when the percentage of recruited lung fell by more than 2% from maximal recruitment achieved during the recruitment phase. Although the ensuing higher airway pressures are a valid concern [31], studies have shown that the implementation of higher PEEP strategies with constant driving pressure does not lead to an increase in adverse outcomes [30, 32].

Sustained inflation (SI) [2]

This was simulated as a sustained pulmonary inflation maneuver, with a positive ventilator pressure of 40 cm H2O applied for 40 s. The end-maneuver PEEP was set to 10 cmH2O.

Results

Model outputs accurately reproduce clinical datasets

The results of matching the model to data from [25–27] on 3 ARDS patients of varying ARDS severity and varying cardiac output are given in Table 1 and Fig. 2, and the results of the model matching to the dataset from [5] on 20 patients stratified by ARDS severity are shown in Table 2 and Fig. 3. All model outputs of interest are consistently very close to the values reported in the clinical data, confirming the ability of the simulator to reproduce physiological responses of individual patients.

Evaluation of the maximal recruitment strategy (MRS) and Sustained inflation (SI) RMs on 3 in silico patients with varying ARDS severity and varying cardiac output

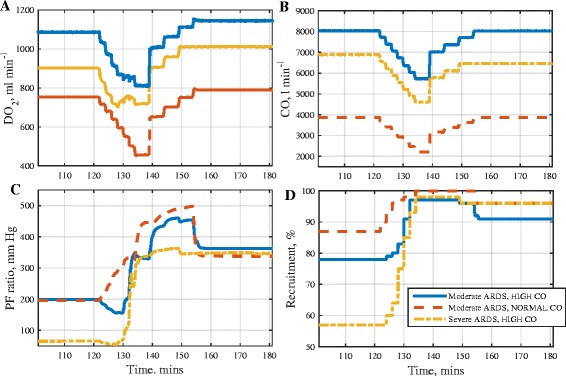

Table 3 shows data on the results of executing the MRS on the 3 in silico ARDS patients from the first datset. Figure 5 shows time courses of oxygen delivery (DO2), CO, PF ratio and percentage of recruited lung. Time courses of right ventricle volume (VRV), physiological shunt (Shunt), PaCO2, MAP, MPAP, SaO2 and SvO2 are provided in the (Additional file 1: Figure S6). Key effects of the MRS maneuver can be summarized as follows:

In all patients, large increases in PF ratio were observed during the application of the MRS, and PF ratio remained significantly greater than baseline values after the RM ended. Improved recruitment, reduced dynamic lung strain, and falls in arterial carbon dioxide levels were evident during and after the RM, indicating an increase in effective lung area and reduced ventilation/perfusion mismatch.

DO2 fell by more than 200 ml min−1 in all three patients at maximum PEEP. This was caused by a decrease in CO which outweighed the increase in oxygen content in all cases, with the lowest CO occurring at maximum PEEP. In one patient (moderate ARDS, normal CO) the level of DO2 during the maneuver fell below 500 ml min−1, which would be likely to cause systemic responses, such as blood flow being redirected to critical organ systems, reducing tissue oxygenation in other tissue beds and potentially leading to residual organ dysfunction.

The end-diastolic volume of the right ventricle fell as PEEP increased in all patients. The end-systolic volume remained relatively constant in the patients with high CO. Both CO and DO2 returned to close-to-baseline levels for the in silico patients with moderate ARDS as PEEP returned to 10 cm H2O.

A significant post-RM increase in DO2 was maintained only in the in silico patient with severe ARDS.

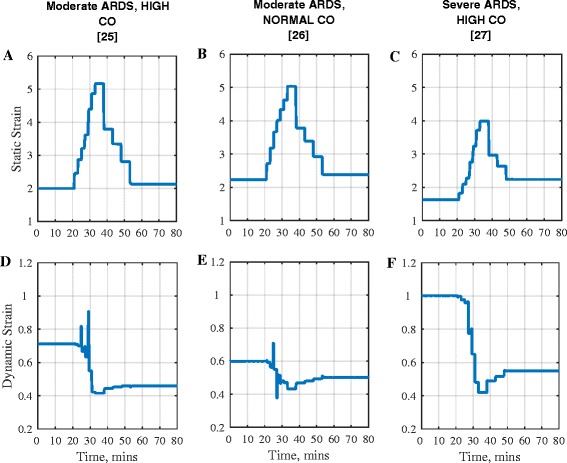

Figure 6 shows that in all in silico patients, the MRS led to an increase in static lung strain and a decrease in dynamic lung strain. The largest decrease in dynamic lung strain was observed in the in silico patient with severe ARDS.

Table 3.

Key results of Recruitment Maneuvers in in silico ARDS patients with varying severity and cardiac output

| Moderate ARDS, High CO [25] | Moderate ARDS, Normal CO [26] | Severe ARDS, High CO [27] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RM | MRS | SI | MRS | SI | MRS | SI |

| End RM PEEP, cm H2O | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 15 | 10 |

| RecruitmentB (baseline), % | 78 | 78 | 8 | 87 | 57 | 57 |

| RecruitmentM (maximum), % | 97 | 80 | 100 | 97 | 98 | 65. |

| R Ratio | 19.59 | 2.50 | 13.00 | 10.31 | 41.84 | 12.31 |

| ∆ CO (at max PAW), l min−1 | −2.3 | −1.7 | −1.6 | −1.2 | −2.3 | −1.5 |

| ∆ RVEDV (at max PAW), ml | −14 | −6 | −55 | −29 | −18 | −10 |

| DO2 (baseline), ml min−1 | 1086 | 1086 | 754 | 754 | 902 | 902 |

| ∆ DO2 (at max PAW), ml min−1 | 810 | 834 | 453 | 540 | 697 | 689 |

| ∆ DO2 (post RM), ml min−1 | 1144 | 1097 | 790 | 786 | 1012 | 971 |

| RAP (baseline), mm Hg | 9 | 9 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 |

| RAP (at max PAW), mm Hg | 18 | 12 | 21 | 15 | 23 | 16 |

| PF ratio (baseline), mm Hg | 199 | 199 | 196 | 196 | 65 | 65 |

| PF ratio (post RM), mm Hg | 363 | 213 | 337 | 309 | 347 | 86 |

List of Abbreviations: RM recruitment maneuver, PEEP positive end expiratory pressure, R Ratio recruitment ratio ((recruitmentM -recruitmentB)/recruitmentB × 100), ∆ CO change in cardiac output relative to baseline, ∆ RVEDV change in right ventricle end diastolic volume relative to baseline, DO 2 oxygen delivery, ∆ DO 2 change in oxygen deliver relative to baseline, PF ratio ratio of arterial partial pressure of oxygen to fraction of oxygen in inhaled air, max P AW maximum airway pressure, RAP right atrial pressures

Fig. 5.

Results of applying the maximum recruitment strategy (MRS) to three in silico ARDS patients. Plots of: a oxygen delivery (DO2), b cardiac output (CO), c ratio of arterial oxygen tension to fraction of oxygen in inhaled air (PF ratio), d % of recruited lung (Recruitment)

Fig. 6.

Strain in three in silico ARDS patient during MRS RM. Static strain in: a Moderate ARDS High CO, b Moderate ARDS Normal CO and c Severe ARDS High CO. Dynamic strain in d Moderate ARDS High CO, e Moderate ARDS Normal CO and f Severe ARDS High CO

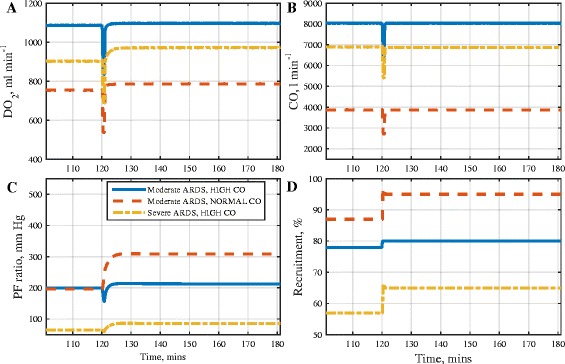

Table 3 also shows the results of executing the SI RM on the 3 in silico ARDS patients. Figure 7 shows time courses of DO2, CO, PF ratio and % of recruited lung. Time courses of other measured variables are provided in the (Additional file 1: Figure S7). Relative to the MRS, the hemodynamic changes during the SI RM lasted for a shorter duration, and its main effects can be summarized as follows:

In the virtual patients with moderate severity ARDS, high CO and severe ARDS, high CO, small numbers of alveoli were re-opened, resulting in only small increases in PF ratio being attained.

Significantly greater recruitment (and hence a larger increase in PF ratio) was observed in the moderate severity ARDS, normal CO subject. However, the resulting gain in oxygen content was effectively cancelled out by the reduction in cardiac output.

Only small post-RM improvements in DO2 were observed in all three virtual patients, with the largest improvement being observed in the severe ARDS subject.

Fig. 7.

Results of applying the sustained inflation (SI) RM in three in silico ARDS patients. Plots of: a oxygen delivery (DO2), b cardiac output (CO), c ratio of arterial oxygen tension to fraction of oxygen in inhaled air (PF ratio),) d % of recruited lung (Recruitment)

Due to the superior performance of the MRS with respect to PF ratio, recruitment, strain and post RM DO2, this RM was selected for further investigation using an additional dataset from a larger cohort of patients reported in [5].

Evaluation of the maximal recruitment strategy RM on 20 in silico patients with varying ARDS severity and high cardiac output

Table 4 shows the results of executing the MRS on 20 in silico ARDS patients, with results listed for subsets of the patients, stratified based on the severity of ARDS. Key effects of the MRS for this in silico patient cohort can be summarized as follows:

PF ratio increased on average by 105 mmHg during the application of the MRS, and remained significantly greater than baseline values afterwards. The biggest improvement in PF ratio was seen in the severe ARDS subgroup. Improved recruitment and reduced dynamic strain were evident for all in silico patients during the MRS.

DO2 fell by more than 150 ml min−1 on average during application of the MRS. This fall in DO2 occurred mostly in the in silico patients with moderate and mild ARDS, whereas in the severe patients DO2 increased by nearly 90 ml min−1 on average during the RM. Due to the high baseline CO of the patients in this cohort, DO2 remained above 1000 ml min−1 in all in silico patients at all times, indicating no risk of tissue de-oxygenation due to application of the RM.

The end-diastolic and end-systolic volume of the right ventricle fell as PEEP increased. The decrease in end-systolic volume was smaller than the decrease in end-diastolic volume, indicating a smaller stroke volume at maximum PEEP. There was a small increase in the right atrial pressure as PEEP was increased.

Table 4.

Key results of Maximum Recruitment Strategy (MRS) in 20 in silico ARDS patients

| All Patients | Severe ARDS | Moderate ARDS | Mild ARDS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean | sd | mean | sd | mean | sd | mean | sd | |

| PEEP (baseline), cmH2O | 10.0 | 0 | 10.0 | 0 | 10.0 | 0 | 10.0 | 0 |

| PEEP (post RM), cmH2O | 24.5 | 2 | 25.0 | 0 | 25.0 | 0 | 21.7 | 6 |

| Recruitment (baseline), % | 63.3 | 18 | 49.7 | 11 | 75.7 | 4 | 88.0 | 11 |

| Recruitment (at max PAW), % | 93.7 | 3 | 92.4 | 2 | 94.2 | 3 | 97.7 | 3 |

| CO (baseline), l min−1 | 11.6 | 0.2 | 11.7 | 0.1 | 11.6 | 0.2 | 11.3 | 0.3 |

| CO (at max PAW), l min−1 | 8.3 | 0.3 | 8.4 | 0.2 | 8.2 | 0.2 | 8.1 | 0.3 |

| CO (post RM), l min-1 | 10.3 | 0.2 | 10.3 | 0.1 | 10.2 | 0.1 | 10.4 | 0.1 |

| ∆ RVEDV (at max PAW), ml | −48 | 6.1 | −49 | 6.2 | −46 | 5.9 | −52 | 4.6 |

| ∆ RVESV (at max PAW), ml | −33 | 21 | −33 | 23 | −43 | 16.2 | −15 | 18 |

| DO2 (baseline), ml min−1 | 1556 | 340 | 1316 | 244 | 1809 | 138 | 1929 | 194 |

| DO2 (at max PAW), ml min−1 | 1398 | 81 | 1406 | 94 | 1385 | 74 | 1403 | 63 |

| DO2 (post RM), ml min−1 | 1642 | 114 | 1595 | 99 | 1671 | 97 | 1759 | 124 |

| PRA (baseline), mmHg | 6.5 | 4 | 6.7 | 4 | 5.5 | 4 | 7.8 | 6 |

| PRA (at max PAW), mmHg | 7.8 | 4 | 8.8 | 4 | 7.3 | 4 | 4.9 | 0 |

| PRA (post RM), mmHg | 7.6 | 4 | 7.4 | 4 | 6.4 | 4 | 10.7 | 0 |

| PF ratio (baseline), mmHg | 102 | 85 | 54 | 10 | 115 | 50 | 250 | 125 |

| PF ratio (at max PAW), mmHg | 206 | 72 | 182 | 53 | 207 | 81 | 298 | 48 |

| PF ratio (post RM), mmHg | 140 | 78 | 92 | 23 | 179 | 82 | 243 | 78 |

| Dynamic strain (baseline), | 0.18 | 0.03 | 0.18 | 0.04 | 0.19 | 0.03 | 0.18 | 0.02 |

| Dynamic strain (at max PAW) | 0.10 | 0.02 | 0.12 | 0..02 | 0.10 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.01 |

List of Abbreviations: RM recruitment maneuver, PEEP positive end expiratory pressure, CO cardiac output, ∆ RVEDV change in right ventricle end diastolic volume relative to baseline, ∆ LVEDV change in left ventricle end diastolic volume relative to baseline, ∆ RVESV change in right ventricle end systolic volume relative to baseline, ∆ LVEDV change in left ventricle end systolic volume relative to baseline, P RA right atrial pressure, DO 2 oxygen delivery, PF ratio ratio of arterial partial pressure of oxygen to fraction of oxygen in inhaled air, max P AW maximum airway pressure

Discussion

Oxygen is essential for cellular metabolism and delivery of sufficient levels of oxygen is vital to preserve organ function. Accordingly, early correction of tissue hypoxia is an important task in management of critically ill patients in intensive care units. DO2 is a well-known and relatively simple surrogate estimate for the oxygen delivered to the cells from the lungs, determined by CO and arterial oxygen content. Although some early studies suggested that there were beneficial outcomes associated with increasing DO2 levels in certain population [33–35], aggressive DO2 targeted protocols were found to be ineffective and potentially harmful in major randomized controlled studies [36, 37]. This was attributed to extreme fluid loading and excessive use of vasoactive agents [36, 38]. High PEEP recruitment maneuvers such as the MRS have shown the potential to increase arterial oxygen content through recruitment of collapsed regions of the lung in ARDS patients, both in clinical trials [30] and in computational studies [16]. This raises the question of whether periodic RMs could be used to improve the delivery of oxygen without the need for aggressive fluid loading, whilst minimizing the continual stress effect of high intrathoracic pressure on the cardiovascular system.

The results of this study indicate that in in silico patients with mild or moderate ARDS, the reduction in cardiac output caused by the RMs (Table 4) could potentially prevent any significant improvements in oxygen delivery that might be expected due to improved gas exchange; this finding is consistent with some previous clinical studies [8, 39]. This phenomenon was more pronounced in those subjects with less severe hypoxia (who therefore had a smaller number of recruitable alveoli), leading to little improvement in DO2 post-RM. This trade-off (which was seen in a substantial patient group) may partly explain the lack of demonstrated outcome benefit seen to date when RMs are applied to non-stratified ARDS patients [40].

In the in silico patients with severe ARDS, with more alveoli available for recruitment, a larger improvement in DO2 was evident after the application of the MRS (Table 4 and Fig. 5a). In fact in the second dataset of 20 in silico patients, an increase in DO2 was observed in those patients with severe ARDS even as PEEP was incremented and CO was falling during the recruitment phase of the RM. This response was also observed in the severe ARDS in silico patient from the first dataset. In this case, DO2 did not fall in tandem with CO during the whole duration of the RM. Between the time interval of 25 and 30 min (Fig. 5a), DO2 actually increased (even while CO continued to fall). The mechanism of rise in DO2 in these cases can be attributed to the substantial increase in alveolar recruitment, enhancing arterial oxygenation. The SI RM, in contrast, produced significantly less recruitment. Thus, the results from our in silico trials suggest that those patients with the most severe acute lung injury may benefit most from high-PEEP recruitment strategies, as also suggested in [41].

Aside from improving oxygenation, another goal of RMs is to reduce the risk of atelectrauma. The strain plots of Fig. 6 and results from Table 3 show that in the in silico patients with higher lung recruitability, higher PEEP and the consequent reduction in tidal opening and closing of alveolar compartments helps in improving dynamic strain. This agrees with data from previous animal studies [24]. This is accompanied by increased static strain as a result of higher end expiratory volumes. Studies have suggested that large static strain may be better tolerated than equivalent dynamic strain [24, 42] and may be beneficial, due to a more homogenous lung ventilation [43].

Several studies have found associations between maintaining sufficient oxygen delivery and positive patient outcomes. For example, it was reported in [35] that maintaining DO2 above 600 ml min−1 m2 was associated with reduced post-surgery complications and shorter hospital stays in post-surgery patients, while DO2 levels of less than 10.9 ml min−1 kg−1 at cardiac index = 3.1 L min−1 m2 were associated with a higher risk of mortality [44]. The potential for substantial negative influence of positive intrathoracic pressure on oxygen delivery is most clearly exhibited in the in silico patient with moderate severity ARDS and normal cardiac output from the first dataset (Fig. 5b). During both RMs, improvements in oxygenation occurred in tandem with large decreases in CO, resulting in DO2 levels falling to values that could potentially lead to organ dysfunction. Neither RM produced a significant long-term improvement in oxygen delivery.

Our results indicate that a higher initial cardiac output may confer relative protection from reductions in stroke volume due to high intrathoracic pressures occurring during RMs. This, however, might not be entirely reflective of all cases of acute cor pulmonale associated with severe ARDS, which can occur in up to a third of these patients [45]. In those instances, volume overload can actually have deleterious effects. We plan to investigate the effects of severe ARDS on the right ventricle as another aspect of heart-lung interactions in subsequent investigations.

The patients in the second dataset have significantly higher baseline values of CO and DO2. These values are consistent with the data in [5], which reported a mean cardiac index of 5.8 l min−1m−2 at Pplat of 30 cmH2O. The relationship between RM based increases in intrathoracic pressure and depression of cardiac output may also be more complicated than suggested by the relatively simplistic initial cardiovascular state stratification of high/low CO presented here. For example, the effect of respiratory variation on inferior vena cava diameter or RAP can result in PEEP induced decreased venous return and cardiac output [10]. In this case, an ARDS patient with sepsis as the trigger, reduced afterload and appropriately managed with a conservative fluid strategy could have a high cardiac output but still be expected to be fluid responsive and have a significant drop in cardiac output during a RM. Yet this would not be seen in a patient with sepsis associated cardiomyopathy with low/normal cardiac output operating on the flat portion of their RV Frank-Starling function curve. Our ability to draw conclusions about the precise presence or absence of cardiopulmonary dysfunction is limited from what is information is available in published data sets. However, we note that cyclical cardiovascular changes in venous, ventricular and arterial systems in response to periodic intrathoracic pressure from ventilation are observable in the model. This signal change is consistent with the dynamic indices of fluid responsiveness in response to tidal ventilation, and we plan to investigate this further during simulated hemorrhage and re-transfusion to help to further calibrate and validate the cardiovascular aspects of our integrated model.

The simulation model used in this study has some limitations. The autonomic reflexes are neglected because, in the studies used for model calibration [5, 25–27], it is likely that the cardiovascular side effects of the drugs and dosages used for sedation suppressed normal cardiovascular system baroreceptor reflexes (these studies consistently reported no significant changes in heart rate throughout their interventions). Effects due to increased cytokine presence in the systemic circulation due to alveolar-capillary membrane damage are not included. Their precise role in terms of isolated systemic effects on the vasculature is difficult to quantify in a clinical setting, since ethical considerations would require some amount of treatment to reverse the adverse effects associated with these changes, such as drugs to improve hypotension. However, we do measure and quantify alveolar strain, which has been established as a reliable surrogate for lung damage that exacerbates barotrauma [24].

Finally, previous studies have shown that the systemic pressure can compensate in response to changes in PEEP, attributed to neuromuscular reflexes [10, 46] and alveolar recruitment can lead to simultaneous recruitment of pulmonary vessels, increasing the vascular volume, and reducing the pulmonary artery pressure [47]. These mechanisms were omitted from the model due to a lack of reliable data for model calibration, and because the drugs and dosages used to produce the type of ventilation seen in the studies on which our model has been calibrated strongly suggest complete muscle relaxation and a constant total body VO2.

Conclusions

An integrated cardiopulmonary computational model was shown to be able to accurately match the cardiorespiratory responses of 23 individual patients with varying severity of ARDS and CO levels. The resulting bank of in silico patients allowed us to perform an in-depth and controlled investigation of the effect of lung recruitment maneuvers on key patient outcome parameters. Our results support the hypothesis that patients with severe ARDS (and hence worse starting VQ mismatch and more alveolar units available for recruitment) may benefit more from RMs. Our results also indicate that a higher than normal initial cardiac output may provide protection against the effects of high intrathoracic pressures associated with RMs on cardiac function. Results from the in silico patients with mild or moderate ARDS suggest that the detrimental effects of RMs on cardiac output can potentially outweigh the positive effects on oxygenation through alveolar recruitment, resulting in overall reductions in tissue oxygen delivery. However, RMs have other potential benefits aside from improved oxygenation, e.g. reduction in atelectrauma. In such patient groups, it may therefore still be useful to administer RMs as long as no dangerous decline in cardiac function is observed. Clinical trials using stratified patient groups could confirm the results of this in silico study and allow the development of more effective guidelines for the application of RMs in ARDS treatment.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding for this study: UK Medical Research Council (grant number MR/K019783/1).

Availability of data and materials

All data used for this study is publically accessible.

Authors’ contributions

JGH, AD, WW and DGB designed and implemented the pulmonary model. MH, AD, and JGH designed and implemented the cardio vascular model. MC, AD and JGH developed the integration between the pulmonary and cardiovascular models. WW, AD and DGB designed the simulation platform for disease simulation and developed algorithms for automated matching of the simulator to individual patient data. OC and MC selected the patient data, analyzed the results, and provided clinical interpretations of simulator outputs. All authors contributed to successive drafts of the manuscript, and read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ARDS

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- CI

Cardiac index [ml min−1 m2]

- CO

Cardiac output [ml min−1]

- CO2

Carbon dioxide

- DO2

Oxygen delivery [ml min−1]

- FIO2

Fraction of inspired air constituting of oxygen.

- Hb

Haemoglobin content in blood [gm l−1]

- IE

Inspiratory to expiratory ratio

- LV

Left ventricle

- MAP

Mean arterial pressure [mm Hg]

- MPAP

Mean pulmonary arterial pressure [mm Hg]

- MRS

Maximum recruitment strategy

- O2

Oxygen

- PaO2

Partial pressure of oxygen in arterial compartment [kpa]

- PEEP

Positive end expiratory pressure [cm H2O]

- Pext

Extrinsic pressure attributed to an alveolar unit in the model [cm H2O]

- PF ratio

Ratio of arterial pressure of oxygen to fraction of oxygen in inspired air

- pHa

Arterial pH value

- PIT

Intrathoracic pressures

- Pplat

Plateau pressure [cm H2O]

- PvO2

Partial pressure of mixed venous oxygen [kpa]

- Ralv

Microbronchial (inlet) resistance attributed to an alveolar unit in the model

- RM

Recruitment maneuver

- RQ

Respiratory quotient

- RV

Right ventricle

- RVEDV

Right ventricle end diastolic volume [ml]

- RVESV

Right ventricle end systolic volume [ml]

- Salv

Alveolar stiffness, attributed to an alveolar unit in the model

- SaO2

Arterial oxygen saturation

- SI

Sustained inflation

- SvO2

Venous oxygen saturation

- TOP

Threshold opening pressure [cm H2O]

- TOPalv

Threshold opening pressure attributed to an alveolar unit in the model [cm H2O]

- VILI

Ventilator induced lung injury

- VO2

Oxygen consumption [ml min−1]

- VQ

Ventilation perfusion

- VR

Respiration rate set by the ventilator [breaths per minute, bpm]

Additional file

Model and Model fitting description and calibration. Contains description of the pulmonary model, cardiac model, cardio pulmonary interactions, model calibration to a healthy state and disease state, selection of patient data, assignment of baseline model parameters, model parameter configuration using optimization, list of parameters used for model fitting, model parameters for simulated patients and healthy state, hemodynamic and pulmonary outputs. (PDF 1930 kb)

Contributor Information

Anup Das, Email: Anup.Das@warwick.ac.uk.

Mainul Haque, Email: mainul.haque@nottingham.ac.uk.

Marc Chikhani, Email: Marc.Chikhani@nottingham.ac.uk.

Oana Cole, Email: minnnie_2000@yahoo.fr.

Wenfei Wang, Email: Wenfei.Wang@warwick.ac.uk.

Jonathan G. Hardman, Email: J.Hardman@nottingham.ac.uk

Declan G. Bates, Email: D.Bates@warwick.ac.uk

References

- 1.Gattinoni L, Caironi P, Cressoni M, Chiumello D, Ranieri VM, Quintel M, Russo S, Patroniti N, Cornejo R, Bugedo G. Lung recruitment in patients with the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(17):1775–1786. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lapinsky SE, Aubin M, Mehta S, Boiteau P, Slutsky AS. Safety and efficacy of a sustained inflation for alveolar recruitment in adults with respiratory failure. Intensive Care Med. 1999;25(11):1297–1301. doi: 10.1007/s001340051061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Engelmann L, Lachmann B, Petros S, Böhm S, Pilz U. ARDS: dramatic rises in arterial PO2 with the ‘open lung’ approach. Crit Care. 1997;1(Suppl 1):054. doi: 10.1186/cc3832. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fan E, Wilcox ME, Brower RG, Stewart TE, Mehta S, Lapinsky SE, Meade MO, Ferguson ND. Recruitment maneuvers for acute lung injury: a systematic review. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178(11):1156–1163. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200802-335OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borges JB, Okamoto VN, Matos GF, Caramez MP, Arantes PR, Barros F, Souza CE, Victorino JA, Kacmarek RM, Barbas CS, et al. Reversibility of lung collapse and hypoxemia in early acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174(3):268–278. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200506-976OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riva DR, Contador RS, Baez-Garcia CS, Xisto DG, Cagido VR, Martini SV, Morales MM, Rocco PR, Faffe DS, Zin WA. Recruitment maneuver: RAMP versus CPAP pressure profile in a model of acute lung injury. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2009;169(1):62–68. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu LL, Aldrich JM, Shimabukuro DW, Sullivan KR, Taylor JM, Thornton KC, Gropper MA. Special article: rescue therapies for acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. Anesth Analg. 2010;111(3):693–702. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181e9c356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grasso S, Mascia L, Del Turco M, Malacarne P, Giunta F, Brochard L, Slutsky AS, Marco RV. Effects of recruiting maneuvers in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome ventilated with protective ventilatory strategy. Anesthesiology. 2002;96(4):795–802. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200204000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luecke T, Pelosi P. Clinical review: Positive end-expiratory pressure and cardiac output. Crit Care. 2005;9(6):607–621. doi: 10.1186/cc3877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fessler HE, Brower RG, Wise RA, Permutt S. Effects of positive end-expiratory pressure on the gradient for venous return. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;143(1):19–24. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/143.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scharf SM, Brown R. Influence of the right ventricle on canine left ventricular function with PEEP. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol. 1982;52(1):254–259. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1982.52.1.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hickling KG. The pressure-volume curve is greatly modified by recruitment. A mathematical model of ARDS lungs. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158(1):194–202. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.1.9708049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Massa CB, Allen GB, Bates JH. Modeling the dynamics of recruitment and derecruitment in mice with acute lung injury. J Appl Physiol. 2008;105(6):1813–1821. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.90806.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Musch G, Harris RS, Vidal Melo MF, O’Neill KR, Layfield JD, Winkler T, Venegas JG. Mechanism by which a sustained inflation can worsen oxygenation in acute lung injury. Anesthesiology. 2004;100(2):323–330. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200402000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ma B, Bates JH. Modeling the complex dynamics of derecruitment in the lung. Ann Biomed Eng. 2010;38(11):3466–3477. doi: 10.1007/s10439-010-0095-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Das A, Cole O, Chikhani M, Wang W, Ali T, Haque M, Bates DG, Hardman JG. Evaluation of lung recruitment maneuvers in acute respiratory distress syndrome using computer simulation. Crit Care. 2015;19(1):8. doi: 10.1186/s13054-014-0723-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hardman J, Bedforth N, Ahmed A, Mahajan R, Aitkenhead A. A physiology simulator: validation of its respiratory components and its ability to predict the patient’s response to changes in mechanical ventilation. Br J Anaesth. 1998;81(3):327–332. doi: 10.1093/bja/81.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Das A, Haque M, Cole O, Chikhani M, Wang W, Ali T, Bates DG, Hardman JG. Development of an Integrated Model of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Physiology for the Evaluation of Mechanical Ventilation Strategy. Milano: 37th IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Conference; 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McNamara MJ, Hardman JG. Hypoxaemia during open-airway apnoea: a computational modelling analysis. Anaesthesia. 2005;60(8):741–746. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2005.04228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hardman JG, Aitkenhead AR. Validation of an original mathematical model of CO2 elimination and dead space ventilation. Anesth Analg. 2003;97(6):1840–1845. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000090315.45491.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Das A, Gao Z, Menon P, Hardman J, Bates D. A systems engineering approach to validation of a pulmonary physiology simulator for clinical applications. J R Soc Interface. 2011;8(54):44–55. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2010.0224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang W, Das A, Ali T, Cole O, Chikhani M, Haque M, Hardman JG, Bates DG. Can computer simulators accurately represent the pathophysiology of individual COPD patients? Intensive Care Medicine Experimental. 2014;2(1):23. doi: 10.1186/s40635-014-0023-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ursino M. Interaction between carotid baroregulation and the pulsating heart: a mathematical model. Am J Phys Heart Circ Phys. 1998;275(5):H1733–H1747. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.5.H1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Protti A, Andreis DT, Monti M, Santini A, Sparacino CC, Langer T, Votta E, Gatti S, Lombardi L, Leopardi O, et al. Lung stress and strain during mechanical ventilation: any difference between statics and dynamics? Crit Care Med. 2013;41(4):1046–1055. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827417a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Biondi JW, Schulman DS, Soufer R, Matthay RA, Hines RL, Kay HR, Barash PG. The effect of incremental positive end-expiratory pressure on right ventricular hemodynamics and ejection fraction. Anesth Analg. 1988;67(2):144–151. doi: 10.1213/00000539-198802000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pinsky MR, Desmet JM, Vincent JL. Effect of positive end-expiratory pressure on right ventricular function in humans. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;146(3):681–687. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/146.3.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jardin F, Farcot JC, Boisante L, Curien N, Margairaz A, Bourdarias JP. Influence of positive end-expiratory pressure on left ventricular performance. N Engl J Med. 1981;304(7):387–392. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198102123040703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crotti S, Mascheroni D, Caironi P, Pelosi P, Ronzoni G, Mondino M, Marini JJ, Gattinoni L. Recruitment and derecruitment during acute respiratory failure: a clinical study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(1):131–140. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.1.2007011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Campos T. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. The Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(18):1302–1308. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Matos GF, Stanzani F, Passos RH, Fontana MF, Albaladejo R, Caserta RE, Santos DC, Borges JB, Amato MB, Barbas CS. How large is the lung recruitability in early acute respiratory distress syndrome: a prospective case series of patients monitored by computed tomography. Crit Care. 2012;16(1):R4. doi: 10.1186/cc10602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Slutsky AS. Lung injury caused by mechanical ventilation. Chest. 1999;116(1 Suppl):9S–15S. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.suppl_1.9S-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Amato MB, Meade MO, Slutsky AS, Brochard L, Costa EL, Schoenfeld DA, Stewart TE, Briel M, Talmor D, Mercat A, et al. Driving pressure and survival in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(8):747–755. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1410639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shoemaker WC, Appel PL, Waxman K, Schwartz S, Chang P. Clinical trial of survivors’ cardiorespiratory patterns as therapeutic goals in critically ill postoperative patients. Crit Care Med. 1982;10(6):398–403. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198206000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shoemaker WC, Appel PL, Kram HB, Waxman K, Lee TS. Prospective trial of supranormal values of survivors as therapeutic goals in high-risk surgical patients. Chest. 1988;94(6):1176–1186. doi: 10.1378/chest.94.6.1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pearse R, Dawson D, Fawcett J, Rhodes A, Grounds RM, Bennett ED. Early goal-directed therapy after major surgery reduces complications and duration of hospital stay. A randomised, controlled trial [ISRCTN38797445] Crit Care. 2005;9(6):R687–R693. doi: 10.1186/cc3887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hayes MA, Timmins AC, Yau EH, Palazzo M, Hinds CJ, Watson D. Elevation of systemic oxygen delivery in the treatment of critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(24):1717–1722. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406163302404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gattinoni L, Brazzi L, Pelosi P, Latini R, Tognoni G, Pesenti A, Fumagalli R. A trial of goal-oriented hemodynamic therapy in critically ill patients. SvO2 Collaborative Group. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(16):1025–1032. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199510193331601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leach RM, Treacher DF. The relationship between oxygen delivery and consumption. Dis Mon. 1994;40(7):301–368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lim SC, Adams AB, Simonson DA, Dries DJ, Broccard AF, Hotchkiss JR, Marini JJ. Intercomparison of recruitment maneuver efficacy in three models of acute lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(12):2371–2377. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000147445.73344.3A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Villar J, Kacmarek RM, Perez-Mendez L, Aguirre-Jaime A. A high positive end-expiratory pressure, low tidal volume ventilatory strategy improves outcome in persistent acute respiratory distress syndrome: a randomized, controlled trial. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(5):1311–1318. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000215598.84885.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Briel M, Meade M, Mercat A, Brower RG, Talmor D, Walter SD, Slutsky AS, Pullenayegum E, Zhou Q, Cook D, et al. Higher vs lower positive end-expiratory pressure in patients with acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;303(9):865–873. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Webb HH, Tierney DF. Experimental pulmonary edema due to intermittent positive pressure ventilation with high inflation pressures. Protection by positive end-expiratory pressure. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1974;110(5):556–565. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1974.110.5.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Caironi P, Cressoni M, Chiumello D, Ranieri M, Quintel M, Russo SG, Cornejo R, Bugedo G, Carlesso E, Russo R, et al. Lung opening and closing during ventilation of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181(6):578–586. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200905-0787OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tuchschmidt J, Fried J, Astiz M, Rackow E. Elevation of cardiac output and oxygen delivery improves outcome in septic shock. Chest. 1992;102(1):216–220. doi: 10.1378/chest.102.1.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jardin F, Vieillard-Baron A. Right ventricular function and positive pressure ventilation in clinical practice: from hemodynamic subsets to respirator settings. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29(9):1426–1434. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-1873-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jellinek H, Krenn H, Oczenski W, Veit F, Schwarz S, Fitzgerald RD. Influence of positive airway pressure on the pressure gradient for venous return in humans. J Appl Physiol. 2000;88(3):926–932. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.88.3.926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gattinoni L, Pesenti A, Baglioni S, Vitale G, Rivolta M, Pelosi P. Inflammatory pulmonary edema and positive end-expiratory pressure: correlations between imaging and physiologic studies. J Thorac Imaging. 1988;3(3):59–64. doi: 10.1097/00005382-198807000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data used for this study is publically accessible.