Abstract

Background:

Sleep disruption and excessive sleepiness are the known consequences of shift work. The recent spate of night-time road and air accidents, with some being directly attributed to driver sleepiness prompted us to undertake this study.

Aims:

To screen for excessive sleepiness, coping practices, and post-shift sleep hygiene in night bus drivers.

Settings and Design:

This prospective study was carried out on night bus drivers of a public transport organization in Bengaluru, Karnataka, India.

Materials and Methods:

Bus drivers driving for ≥8 h at night were screened with the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) and a prevalidated shift work questionnaire.

Statistical Analysis:

Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the compiled data using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20.

Results:

One hundred and eighty bus drivers aged 22–63 years were screened.

Excessive Sleepiness:

Although only 2 (1.1%) drivers scored above the cutoff on ESS, 10 (5.6%) and 103 (57.2%) drivers admitted to feeling sleepy during daytime and night driving respectively. None of the drivers admitted to causing accidents related to sleepiness. The coping strategies for nocturnal sleepiness included consuming coffee/tea (16.7%), chewing tobacco (12.8%), smoking (6.1%), and walking (3.9%).

Post-Shift Sleep Practices:

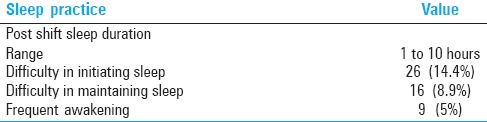

Post-shift sleep duration ranged between 1 h and 10 h. Twenty-six (14.4%) and 16 (8.9%) drivers had difficulty initiating and maintaining sleep, respectively, while 9 (5%) reported frequent awakening during daytime sleep.

Conclusion and Implications:

This study has demonstrated a high incidence of nocturnal sleepiness and daytime sleep disruption among night bus drivers, thus necessitating the need for education about shift work and alertness testing among shift workers in critical professions.

Key words: Bus drivers, excessive sleepiness, shift work, sleep hygiene

INTRODUCTION

Shift work is an integral part of many professions such as emergency services, health care, transport, and defence sectors. The term shift worker is used to describe someone who works outside the normal daylight hours. This might involve rotating or fixed night shifts. Shift work is known to disrupt circadian rhythms and compromise sleep. In the short term, sleep debt may result in critical errors at the workplace as well in tasks requiring vigilance outside the workplace such as driving. In the long term, the latter can result in shift work sleep disorder (SWSD).

Apart from the abovementioned consequences of shift work, sleep disorders unrelated to shift work may also cause excessive sleepiness. Bus drivers form an important subset of shift workers and the presence of an undiagnosed sleep disorder in them could lead to road accidents. A consensus statement[1] endorsed by a group of scientists states that “fatigue (sleepiness, tiredness) is the largest identifiable and preventable cause of accidents in transport operations (between 15% and 20% of all accidents), surpassing that of alcohol- or drug-related incidents in all modes of transportation.”

It has also been reported that relatively moderate levels of sleepiness impair performance to an extent that is equivalent to or greater than that currently acceptable for alcohol intoxication.[2]

The present study was conducted to screen the presence of excessive sleepiness and post-shift sleep practices amongst a cohort of bus drivers working in night shifts.

Objective

To screen for daytime and nocturnal (on-shift) sleepiness, coping practices, and post-shift sleep hygiene in night bus drivers using prevalidated questionnaires.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Inclusion criteria

Bus drivers working for the Karnataka State Road Transport Corporation (KSRTC) on long haul routes (more than 150 km) in rotating night shifts (10 PM to 6 AM) were included.

Exclusion criteria

The following subjects were excluded:

Those who were on sedatives or wake promoting drugs

Those who had already been diagnosed to have a sleep disorder and were on treatment for the same.

Methods

The study subjects were selected from a cohort of about 25,000 night shift drivers in the KSRTC using the simple random selection technique. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Strict confidentiality was maintained throughout the study. Demographic data (name, age, gender) and relevant medical history were recorded and compiled.

All subjects were administered the following questionnaires [Tables 1 and 2]

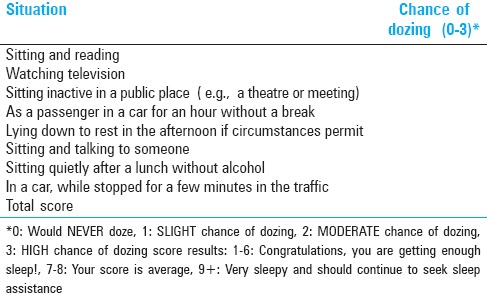

Table 1.

Epworth sleepiness scale

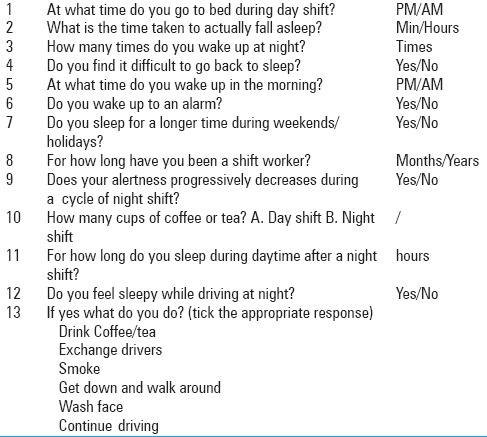

Table 2.

Pre validated shift worker questionnaire

Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS)[3]

A prevalidated questionnaire to screen sleep habits, shift schedules, coping practices, and sleepiness during shift work and post-shift sleep hygiene.

The questionnaires were administered in the local language by the medical researcher and the responses were tabulated.

Sample size and statistical analysis

The sample size was estimated using nMaster 2.0 sample size calculator (Department of Biostatistics, CMC, Vellore) based on a study by Howard et al.[4] where 24% of commercial vehicle drivers were found to have excessive sleepiness. A sample size of 304 drivers was arrived at by considering an alpha error of 5% with 90% power. Based on preliminary analysis of the data collected from 100 drivers, the sample size was further reduced to 180.

Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the compiled data. The frequency of excessive sleepiness and/or suspected sleep disorders were expressed in percentage and its 95% confidence interval was analyzed.

RESULTS

Demographic profile

One hundred and eighty male bus drivers who satisfied the inclusion criteria stated in the protocol were screened. The age of the drivers ranged between 22 years and 63 years [mean ± standard deviation (SD): 41.4 ± 9.3 years]. The duration of shift work ranged between 0.5 years and 35 years (mean ± SD: 12.9 ± 8.2 years), and the duration of night-time driving ranged 8–14 h.

Sixteen drivers (8.9%) reported comorbidities as follows: 9 (5%) had diabetes mellitus; 6 (3.3%) had hypertension, and 1 (0.6%) had hypercholesterolemia [Table 3].

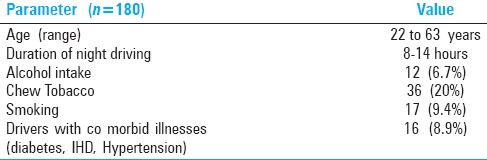

Table 3.

Demographic data

Twelve (6.7%) of the drivers admitted to consuming alcohol, 17 (9.4%) were smokers, and 36 (20%) chewed tobacco.

Sleepiness evaluation

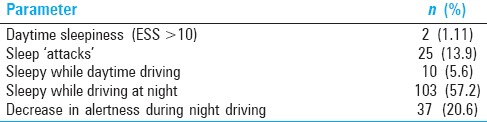

Only 2 (1.1%) of the bus drivers scored ≥9 on the ESS, implying a significant level of daytime sleepiness. However, 10 (5.6%) drivers confessed to feeling sleepy during the day while stopping in traffic and 103 (57.2%) drivers admitted to feeling sleepy while driving at night.

Twenty-five (13.9%) of them reported experiencing “sleep attacks” and 37 (20.6%) drivers reported a decrease in alertness as the shift progressed [Table 4].

Table 4.

Evaluation of sleepiness

On statistical analysis, it was found that sleepiness significantly decreased with increasing duration of shift work (P 0.026), which indicates that bus drivers get habituated to night shifts. Sleepiness during night-time driving significantly decreased in those drivers who had sleep maintenance insomnia prior to commencing night shift-related job (P 0.040).

However, it was found that the daytime sleep duration after night shift did not correlate with sleepiness while night-time driving (P 0.262).

Further, no association was found between difficulty in sleep initiation and being sleepy while driving at night (P 0.797) and as well as between daytime sleepiness and feeling sleepy while driving at night (P 0.362).

Coping strategies

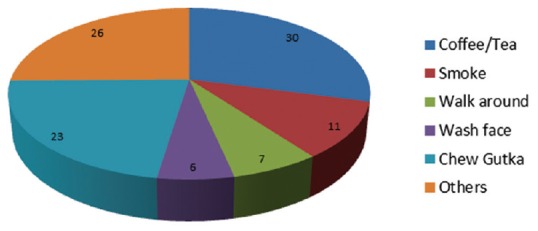

As mentioned earlier, 103 drivers felt sleepy during the night shift. The various coping strategies adopted by them have been depicted in Figure 1. Coping strategies for nocturnal sleepiness included consuming coffee/tea (16.7%), chewing tobacco (12.8%), smoking (6.1%), and walking (3.9%).

Figure 1.

Coping strategies adopted in night shifts

Evaluation of post-shift work-sleep practices

One hundred and seventy five (97.2%) slept during the day after the completion of a night shift. The duration of this daytime sleep ranged between 1 h and 10 h (mean ± SD: 5.14 ± 1.84 years). Fifty-eight (32.2%) drivers said that they caught up on sleep by sleeping for longer durations during holidays and weekends. During this catch-up sleep as well as during night-time sleep during nonshift periods, 26 bus drivers (14.4%) found it difficult to initiate sleep, 9 (5%) drivers complained of disrupted sleep as they woke up more than twice every night, and 16 (8.9%) reported the inability to fall asleep after nocturnal awakenings [Table 5].

Table 5.

Post shift sleep practices

DISCUSSION

This study has demonstrated a high proportion of sleepiness in drivers working on long haul night shifts, which is in concordance with that reported in studies conducted in other parts of the world. A few of these studies are reviewed below and their results have been compared with the results of our study.

A study[5] by Akerstedt has revealed the chronic effects of long-term night shifts, which are comparable to clinical insomnia in reducing productivity of the workforce. Several previously conducted studies have demonstrated the association between night shift work and self-reported sleepiness in train drivers,[6] truck drivers,[7] and process operators,[8] among others. An increased risk of road accidents has also been reported when driving home after a night shift.[9,10] In our study too, we have demonstrated a high proportion of self-reported on-shift sleepiness (57.22%) and also a decrease in alertness as the shift progressed in 37 bus drivers (20.6%). In addition, we have attempted to study post-shift sleep hygiene practices and the methods adopted by Indian bus drivers to cope with sleepiness during the night shift.

A survey conducted in England by Horne et al.[11] found that sleep-related incidents comprised 16–20% of all police-attended motor vehicle crashes. A recent study on the top five causes for road accidents in India, Nepal, and Zimbabwe by Pearce et al.[12] has revealed that driver error was the major factor in 74% of bus accidents. As our study involved only self-administered questionnaires; the statistics of actual vehicle crashes related to sleepiness could not be compiled.

Some limitations of our study were as follows: The methodology used self-reporting as a means of obtaining data, which may have underestimated the proportion of sleepiness and its role in the causation of accidents/near-misses, lack of real-time monitoring, and performance of in-laboratory tests such as the maintenance of wakefulness test (MWT). Nevertheless, the findings reported in this study reiterate the need for further research aimed at real-time monitoring of alertness in bus drivers as well as in other critical professions.

Thus, this study could be considered as the initial step toward detection of undiagnosed shift work-related sleep disorders among public transport vehicle drivers. If simple questionnaire-based methods as described in our study could be routinely employed in preemployment and periodic screening of night shift drivers, timely referral for further evaluation and treatment for sleep disorder(s) could be enforced. This would go a long way in reducing the number of road traffic accidents related to sleepiness.

Apart from this, the existence of a database related to the patterns and prevalence of driver sleepiness could help in modifying existing work schedules to avert accidents and near-misses. Some measures to achieve this may include education about sleep hygiene, good post-shift sleep practices, programed naps during shifts, and the controlled use of caffeine to promote wakefulness during shifts.

Thus, this study could be considered a forerunner for future research aimed at improving road safety standards, especially with respect to reducing critical but avoidable human errors.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We thank Gaurav Gupta, former Managing Director (MD) (KSRTC) and all the bus drivers for their help and cooperation, and for granting us the permission to interview them soon after their night shifts.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akerstedt T. Consensus statement: Fatigue and accidents in transport operations. J Sleep Res. 2000;9:395. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2000.00228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dawson D, Reid K. Fatigue, alcohol and performance impairment. Nature. 1997;388:235. doi: 10.1038/40775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johns MW. Reliability and factor analysis of the Epworth Sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1992;15:376–81. doi: 10.1093/sleep/15.4.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howard ME, Desai AV, Grunstein RR, Hukins C, Armstrong JG, Joffe D, et al. Sleepiness, sleep-disordered breathing, and accident risk factors in commercial vehicle drivers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:1014–21. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200312-1782OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akerstedt T. Shift work and disturbed sleep/wakefulness. Sleep Med Rev. 1998;2:117–28. doi: 10.1016/s1087-0792(98)90004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Torsvall L, Akerstedt T. Sleepiness on the job: Continuously measured EEG changes in train drivers. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1987;66:502–11. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(87)90096-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kecklund G, Akerstedt T. Sleepiness in long distance truck driving: An ambulatory EEG study of night driving. Ergonomics. 1993;36:1007–17. doi: 10.1080/00140139308967973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Torsvall L, Akerstedt T, Gillander K, Knutsson A. Sleep on the night shift: 24-hour EEG monitoring of spontaneous sleep/wake behavior. Psychophysiology. 1989;26:352–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1989.tb01934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stutts JC, Wilkins JW, Scott Osberg J, Vaughn BV. Driver risk factors for sleep-related crashes. Accid Anal Prev. 2003;35:321–31. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4575(02)00007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ohayon MM, Lemoine P, Arnaud-Briant V, Dreyfus M. Prevalence and consequences of sleep disorders in a shift worker population. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:577–83. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00438-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horne JA, Reyner LA. Sleep related vehicle accidents. BMJ. 1995;310:565–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6979.565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maunder DA, Pearce TC. Bus accidents: An additional burden for the poor. CODATU IX Conference; 11-14 April 2000; Mexico City. [Google Scholar]