Abstract

Background/Aims

In gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma, the clinical significance of various endoscopic findings has not yet been determined. This study aimed to compare the time to complete remission (CR) and relapse-free survival (RFS) in gastric MALT lymphoma based on endoscopic findings.

Methods

In this single-center retrospective cohort study, the medical records of 122 consecutive adult patients with gastric MALT lymphoma were collected over a period of 12 years. CR was defined by the absence of macroscopic or microscopic features of lymphoma on two subsequent follow-ups. Relapse was clinically defined by a positive endoscopic biopsy after CR.

Results

The median time to CR did not differ significantly between treatment methods. However, it was significantly longer in the group with polypoid endoscopic appearance than in the groups with diffuse infiltration or ulceration (7.83, 3.43, and 3.10 months, respectively; p=0.003). Six patients relapsed after CR. Kaplan-Meier analysis showed that RFS differed significantly between groups based on Ann Arbor staging, treatment methods, and initial endoscopic findings.

Conclusions

In gastric MALT lymphoma, the endoscopically defined polypoid type was characterized by a longer duration to CR, with a higher likelihood of recurrence, compared to the endoscopically defined diffuse infiltration or ulceration types.

Keywords: Endoscopy; Familial primary gastric lymphoma; Lymphoma, B-cell, marginal zone; Recurrence

INTRODUCTION

The treatment method for gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma is determined according to the clinical stage and Helicobacter pylori (HP) infection status [1,2]. HP eradication is recommended regardless of the clinical stage, even in HP-negative cases [2,3]. In cases of early-stage MALT lymphoma, approximately 75% of patients with successful HP eradication achieved complete remission (CR) [4]. In advanced stages, residual disease after HP eradication, or HP-negative cases, radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy can be administered subsequently [1,2].

The mean time to histological remission after HP eradication was 5 months (range, 1 to 14) [5,6]. The guidelines recommend a watch and wait strategy, in which endoscopic biopsies are performed every 3 to 6 months for a period of at least 12 months [1,2].

It appears that low-grade MALT lymphoma has good prognosis irrespective of the treatment method used [7-9]. In 1992, Radaszkiewicz et al. [10] reported that the 5-year cumulative incidence of relapse after radical tumor resection was 22% for gastric MALT lymphoma. In a preceding study, Pinotti et al. [11] had reported that the 5-year projected event-free survival rate was 67% (events defined as relapse or death) for low-grade MALT lymphoma. In a 2010 systematic review, Zullo et al. [4] reported that the recurrence rate for early-stage MALT lymphoma after HP eradication was 2.2% per year.

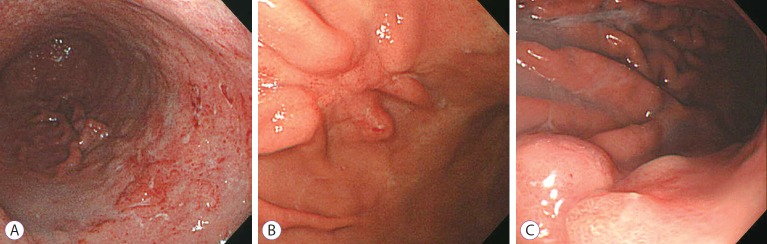

We classified gastric MALT lymphoma into diffuse infiltration, ulceration, and polypoid types based on the major macroscopic appearances [12]. On the other hand, Kolve et al. [13] classified gastric MALT lymphoma into the polypoid, exulcerative, ulcerative-infiltrative, and diffuse-infiltrative types based on the endoscopic appearances, while others classified it into five types based on strictly defined endoscopic findings [14,15]. There have been several attempts at using endoscopic classification in the diagnosis of MALT lymphoma [16,17]. However, the clinical significance of endoscopic classification for the diagnosis of gastric MALT lymphoma is controversial. The aim of this study was to compare the time to CR and relapse-free survival (RFS) between different endoscopic types of gastric MALT lymphoma.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of 158 consecutive adult patients diagnosed with gastric MALT lymphoma at Seoul National University Bundang Hospital between April 2003 and March 2015. Thirty-six patients who did not achieve CR were excluded, while the remaining 122 patients who achieved CR were included. This study was conducted in accordance with the amended Declaration of Helsinki. The Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Bundang Hospital reviewed and approved the protocol (B-1507-306-125).

Diagnosis, treatment, and endoscopic findings

All patients were diagnosed using endoscopic biopsies based on histomorphological criteria in accordance with the World Health Organization classification. Patients without histological confirmation were excluded. In addition, patients with other malignancies, including diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, as well as MALT lymphoma involving parts of the gastrointestinal tract other than the stomach, were excluded. Most patients underwent HP testing including modified Giemsa staining, rapid urease testing, cultures, or urea breath tests. Radiologic evaluations including computed tomography were also performed for staging. Some patients underwent endoscopic ultrasonography and bone marrow biopsy. A minority of patients underwent MALT1 gene rearrangement tests using fluorescence in situ hybridization.

The attending physicians determined the appropriate treatment for each patient depending on the HP infection status, chromosomal translocations, and clinical stage, including lymph node involvement and submucosal invasion. The majority of the subjects with HP infection and early stage cancer were treated with HP eradication. For HP-negative cases or cases with no response to eradication, radiotherapy was administered. When regional lymph nodes around the stomach were involved, radiotherapy was administered as the first-line treatment, with or without HP eradication. For the more advanced stages, such as modified Ann Arbor stage IIIE or IVE [18], the first-line treatment was chemotherapy with or without HP eradication. In patients who did not achieve CR after radiotherapy with or without HP eradication, chemotherapy was administered as a second-line treatment.

The treatment method was determined as HP eradication, radiotherapy, or chemotherapy, based on the treatment that resulted in CR, irrespective of whether it was the first- or second-line choice. In most patients, follow-up esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) was performed every 3 to 6 months until CR was achieved. After achieving CR, EGD was performed every 1 to 2 years. Two endoscopists reviewed the endoscopic findings of each patient and classified them into diffuse infiltration, ulceration, or polypoid lesion categories based on the study by Taal et al. (Fig. 1) [12].

Fig. 1.

Endoscopic findings on gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. (A) Diffuse infiltrative type with multiple erosions and hyperemic patches. (B) Ulcerative type. (C) Polypoid type with focal fold thickening.

CR and relapse

According to the histological grading system proposed by the Groupe d’Etude des Lymphomes de l’Adult, CR is defined as the lack of macroscopic features of lymphoma, and negative histology (complete histological response or probable minimal residual disease) on two subsequent follow-ups [1,19]. A complete histologic response was defined by normal or empty lamina propria and/or fibrosis with absent or scattered plasma cells, and small lymphoid cells in the lamina propria without lymphoepithelioid lesions. Probable minimal residual disease was defined as empty lamina propria and/or fibrosis with aggregates of lymphoid cells or lymphoid nodules in the lamina propria/muscularis mucosa and/or submucosa without lymphoepithelioid lesions.

Relapse was clinically defined by a positive endoscopic biopsy and a Wotherspoon score of 4 to 5 at follow-up after CR [20]. Transient or stable lymphoid aggregates without lymphoepithelioid lesions were excluded from the definition of a relapse.

Statistical analysis

For two-group comparisons, Pearson chi-square test, or Fisher exact test (in situations with small frequencies) was used for categorical variables, and the Mann-Whitney U test was used for continuous variables. For three-group comparisons, Pearson chi-square test, or Fisher exact test (in situations with small frequencies) was used for categorical variables, and the Kruskal-Wallis H test was used for continuous variables. The RFS and cumulative incidence of relapse were analyzed using Kaplan-Meier analysis, and the comparison of differences between groups according to clinical stage, treatment method, and endoscopic findings, was performed using the log rank test. A p<0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 22.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

The mean age was 52.1±11.3 (standard deviation [SD]) years at diagnosis, and 68 patients (55.7%) were men. The median follow-up duration was 2.6 years (interquartile range [IQR], 1.0 to 5.1). Thirteen patients (10.7%) had a chronic viral hepatitis B infection. Of the 122 patients, 98 (80.3%) tested positive for HP. In patients with HP infection, only two patients (2%) did not undergo HP eradication. Seventy-eight patients (79.6%) and 18 patients (18.4%) showed successful eradication of HP after first-line and second-line treatment, respectively. Among 24 patients without HP infection, 15 (62.5%) underwent HP eradication.

Among the 122 patients, 96 (78.7%), 19 (15.6%), and seven patients (5.7%) achieved CR after HP eradication without other treatments, with radiotherapy with or without HP eradication, and with chemotherapy, respectively. According to the endoscopic classification, 61 (50.0%), 43 (35.2%), and 18 patients (14.8%) were classified into the diffuse infiltration, ulceration, or polypoid types, respectively.

The proportion of advanced stage patients with polypoid type was significantly higher than those with the diffuse infiltration or ulceration types, and the proportion of patients receiving chemotherapy was significantly higher in patients with the polypoid type than in those with the diffuse infiltration and ulceration types (Table 1). However, the other variables did not differ significantly.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics according to the Endoscopic Classification of Low-Grade Gastric Mucosa-Associated Lymphoid Tissue Lymphoma

| Characteristic | Total (n=122) | Diffuse infiltration (n=61) | Ulceration (n=43) | Polypoid (n=18) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 52.1±11.3 | 52.6±9.7 | 50.9±12.7 | 53.3±13.1 | 0.716 |

| Male sex | 68 (55.7) | 34 (55.7) | 25 (58.1) | 9 (50.0) | 0.843 |

| HBsAg, positive | 13 (10.7) | 8 (13.1) | 4 (9.3) | 1 (5.6) | 0.782 |

| MALT1-FISH | 0.121 | ||||

| Positive | 4 (36.4) | 3 (50.0) | 0 | 1 (100.0) | |

| Negative | 7 (63.6) | 3 (50.0) | 4 (100.0) | 0 | |

| Ann Arbor stage | 0.005 | ||||

| IE | 92 (88.5) | 49 (94.2) | 33 (89.2) | 10 (66.7) | |

| IIE | 6 (5.8) | 1 (1.9) | 4 (10.8) | 1 (6.7) | |

| IIIE | 2 (1.9) | 1 (1.9) | 0 | 1 (6.7) | |

| IVE | 4 (3.8) | 1 (1.9) | 0 | 3 (20.0) | |

| T stage on EUS | 0.244 | ||||

| T1a | 10 (28.6) | 7 (43.8) | 2 (15.4) | 1 (16.7) | |

| T1b | 10 (28.6) | 3 (18.8) | 4 (30.8) | 3 (50.0) | |

| T2 | 13 (37.1) | 5 (31.3) | 7 (53.8) | 1 (16.7) | |

| T3 | 2 (5.7) | 1 (6.3) | 0 | 1 (16.7) | |

| HP infection | 0.888 | ||||

| Positive | 98 (80.3) | 48 (78.7) | 35 (81.4) | 15 (83.3) | |

| Negative | 24 (19.7) | 13 (21.3) | 8 (18.6) | 3 (16.7) | |

| HP eradication | 0.955 | ||||

| No eradication | 11 (9.0) | 6 (9.8) | 3 (7.0) | 2 (11.1) | |

| First-line regimen | 92 (75.4) | 45 (73.8) | 34 (79.1) | 13 (72.2) | |

| Second-line regimen | 19 (15.6) | 10 (16.4) | 6 (14.0) | 3 (16.7) | |

| Treatment | 0.036 | ||||

| HP eradication only | 96 (78.7) | 47 (77.0) | 37 (86.0) | 12 (66.7) | |

| Radiotherapy | 19 (15.6) | 11 (18.0) | 6 (14.0) | 2 (11.1) | |

| Chemotherapy | 7 (5.7) | 3 (4.9) | 0 | 4 (22.2) | |

| Duration of follow-up, mo | 31.7 (11.7–61.7) | 28.5 (13.3–60.5) | 32.1 (9.0–66.2) | 35.7 (24.2–84.0) | 0.401 |

| Duration from treatment initiation to CR, mo | 3.5 (2.7–6.2) | 3.4 (2.7–5.5) | 3.1 (2.3–5.0) | 7.8 (4.3–10.3) | 0.003 |

| Duration from CR to relapse, mo | 26.9 (10.2–32.1) | 32.1 (32.1–32.1) | 28.7 (6.8–50.5) | 22.8 (10.2–31.0) | 0.800 |

Values are presented as mean±SD, number (%), or median (interquartile range).

HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; MALT1-FISH, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma-associated translocation 1-fluorescence in situ hybridization; EUS, endoscopic ultrasonography; HP, Helicobacter pylori; CR, complete remission.

Time to CR after treatment initiation

The median time from treatment initiation to CR was 3.5 months (IQR, 2.7 to 6.2) (Table 1). The median time to CR did not differ significantly between the HP eradication, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy groups (3.8, 3.0, and 4.2 months, respectively; p=0.764). However, this was significantly longer for the polypoid type than for the diffuse infiltration or ulceration types (3.4, 3.1, and 7.8 months, respectively; p=0.003). The median time to CR for the ulceration type did not differ from the diffuse infiltration type.

RFS

Six (4.9%) out of 122 patients relapsed after CR. The median time to relapse after CR was 26.9 months (IQR, 10.2 to 32.1). All the relapses were observed within 5 years. In total, one, two, and three patients relapsed in the diffuse infiltrative, ulcerative, and polypoid groups, respectively. Among the patients with relapse, the diffuse infiltrative type, ulcerative type, and polypoid type were observed in one, two, and three patients, respectively. At relapse, the follow-up endoscopic types were consistent with the initial endoscopic types for all patients.

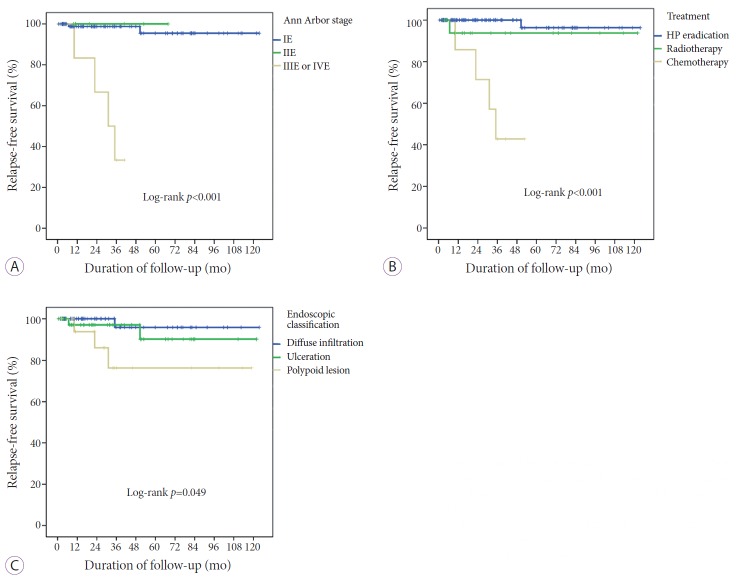

Kaplan-Meier analysis showed that relapse occurred more frequently and earlier in the advanced stage disease (modified Ann Arbor stage IIIE or IVE) than in early stage disease (modified Ann Arbor stage IE or IIE; log rank, p<0.001) (Fig. 2A). For cases with advanced stage disease (Ann Arbor stage IIIE or IVE), the 3-year RFS rate was 33.3%. In contrast, the 3-year RFS rates for Ann Arbor stages IE and IIE were 98.7% and 100%, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of relapse-free survival (RFS). (A) Kaplan-Meier estimates of RFS based on the Ann Arbor stage. Blue, green, and yellow curves represent stages IE, IIE, and IIE/IVE, respectively. (B) Kaplan-Meier estimates of RFS based on the treatment type. Blue, green, and yellow curves represent Helicobacter pylori (HP) eradication, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy, respectively. (C) Kaplan-Meier estimates of RFS based on endoscopic appearance. Blue, green, and yellow curves represent diffuse infiltration, ulceration, and polypoid types, respectively.

In addition, the cumulative relapse rate of the chemotherapy group was higher than that of the HP eradication or radiotherapy groups (log rank, p<0.001) (Fig. 2B). The relapse rate of the HP eradication group did not differ significantly from the radiotherapy group (log rank, p=0.229). The 3-year RFS of the chemotherapy group was significantly lower than that of the HP eradication and radiotherapy groups (p<0.001, 42.9% vs. 100%; p=0.032, 42.9% vs. 93.8%, respectively).

In particular, the RFS of the polypoid group was significantly worse than that of the diffuse infiltration or ulceration group (log rank, p=0.024) (Fig. 2C). The 5-year RFS rate was 76.4% in the polypoid type. There was no significant difference in the 5-year RFS rates between the diffuse infiltration and ulceration types (p=0.414, 95.8% vs. 90.1%).

Patients without HP eradication had tendencies to relapse more frequently compared to the patients with successful HP eradication (5-year RFS rates, log rank, p=0.003, 66.3% vs. 94.0%).

DISCUSSION

In this study, the possible correlation between endoscopic findings and recurrence rate in gastric MALT lymphoma was investigated. It appeared that patients with polypoid type on initial endoscopy had a higher likelihood of recurrence than those with diffuse infiltration or ulceration types. Yokoi et al. [21] identified eight patients with a polypoid appearance among 96 patients with gastric MALT lymphoma in Japan in 1999. They reported that the mean overall survival for polypoid cases was 21.0±20.9 months, and six of the eight patients achieved CR after total gastrectomy. Among the eight patients with a polypoid appearance on endoscopy, six had low-grade gastric MALT lymphoma, and two had high-grade gastric MALT lymphoma. They asserted that gastric MALT lymphoma cases with polypoid findings might be regarded as intestinal-type, and can be distinguished from lesions with other appearances, because their features resembled those of colorectal MALT lymphoma. Interestingly, they also reported a lower HP positivity in the polypoid lesions than in superficial/erosive or ulcerative lesions (37.5% vs. 86.7%, respectively). On the contrary, in our study, HP positivity did not differ significantly between the polypoid type and the diffuse infiltration or ulceration types (p=0.888).

In addition to the endoscopic findings, a correlation was identified between recurrence and the Ann Arbor staging and treatment methods. Although we aimed to identify the essential predictive factor(s) for relapse in gastric MALT lymphoma, we could not identify any significant factors using the Cox proportional hazards model. Although there was no significant collinearity between endoscopic findings, Ann Arbor stage, and/or treatment when variance inflation factors were used, statistical significance was not achieved with any multivariate model by Cox proportional hazards analysis. One of the three variables could be a potential confounding factor; however, the most important predictive factor could not be identified. Therefore, prospective randomized studies for gastric MALT lymphoma with a polypoid appearance on endoscopy are required.

The median time to CR after treatment was 3.5 months (IQR, 2.7 to 6.2) for all patients with MALT lymphoma. In subgroup analysis based on endoscopic appearance, the median time to CR was significantly longer in the polypoid type than in the diffuse infiltration or ulceration types. This finding might be attributed to a higher proportion of advanced-stage patients with polypoid type who received chemotherapy treatment than patients with other types. However, although the proportion of advanced stage patients was higher in the chemotherapy group than in the HP eradication or radiotherapy groups, the median time to CR did not differ significantly between the three treatment groups. Therefore, these results imply that polypoid findings on endoscopy have some clinical significance, regardless of clinical stage or treatment method. Furthermore, several previous studies reported that the polypoid type is more common in high-grade gastric MALT lymphoma than in low-grade gastric MALT lymphoma [14,15]. In the present study, all patients with high-grade gastric MALT lymphoma were excluded, including those with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Although all patients enrolled in the present study had histologically proven low-grade gastric MALT lymphomas, the polypoid appearance was significantly associated with an advanced Ann Arbor stage.

A limitation of this retrospective study was the heterogeneity among the enrolled patients, including HP eradication, the timing of the treatment, and the differences in treatment methods according to the clinical stage. We could not assess overall survival, because none of the enrolled patients died. In this study, 4.9% (six out of 122 patients) relapsed within 50 months; however, there was no relapse after 5 years. This relapse rate was lower than that observed in previous studies [4,10,11], because only patients who achieved CR were enrolled in this study. Nevertheless, it appeared that there was a significant difference in the RFS of patients based on the clinical Ann Arbor stage, treatment method, and endoscopic findings.

In conclusion, polypoid appearance on initial endoscopy was linked to the clinical course of gastric MALT lymphoma. Cases of gastric MALT lymphoma with a polypoid appearance required a longer time to CR, and had higher likelihood of recurrence than those with diffuse infiltration or ulceration appearance on endoscopy. The polypoid appearance on initial endoscopy might indicate the necessity for a different strategy during the clinical follow-up of low-grade gastric MALT lymphoma.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to J. Patrick Barron, Professor Emeritus, Tokyo Medical University, and Adjunct Professor, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital for his pro bono editing of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ruskoné-Fourmestraux A, Fischbach W, Aleman BM, et al. EGILS consensus report. Gastric extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of MALT. Gut. 2011;60:747–758. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.224949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zucca E, Copie-Bergman C, Ricardi U, et al. Gastric marginal zone lymphoma of MALT type: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2013;24 Suppl 6:vi144–vi148. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dreyling M, Thieblemont C, Gallamini A, et al. ESMO consensus conferences: guidelines on malignant lymphoma. Part 2: marginal zone lymphoma, mantle cell lymphoma, peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:857–877. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zullo A, Hassan C, Cristofari F, et al. Effects of Helicobacter pylori eradication on early stage gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:105–110. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Isaacson PG. Gastric MALT lymphoma: from concept to cure. Ann Oncol. 1999;10:637–645. doi: 10.1023/a:1008396618983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sackmann M, Morgner A, Rudolph B, et al. Regression of gastric MALT lymphoma after eradication of Helicobacter pylori is predicted by endosonographic staging. MALT Lymphoma Study Group. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:1087–1090. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v113.pm9322502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim SJ, Yang S, Min BH, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication for stage I(E1) gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma: predictive factors of complete remission. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2010;55:94–99. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2010.55.2.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ryu KD, Kim GH, Park SO, et al. Treatment outcome for gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma according to Helicobacter pylori infection status: a single-center experience. Gut Liver. 2014;8:408–414. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2014.8.4.408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suzuki H, Saito Y, Hibi T. Helicobacter pylori and gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma: updated review of clinical outcomes and the molecular pathogenesis. Gut Liver. 2009;3:81–87. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2009.3.2.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Radaszkiewicz T, Dragosics B, Bauer P. Gastrointestinal malignant lymphomas of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue: factors relevant to prognosis. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:1628–1638. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)91723-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pinotti G, Zucca E, Roggero E, et al. Clinical features, treatment and outcome in a series of 93 patients with low-grade gastric MALT lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 1997;26:527–537. doi: 10.3109/10428199709050889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taal BG, den Hartog Jager FC, Tytgat GN. The endoscopic spectrum of primary non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the stomach. Endoscopy. 1987;19:190–192. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1018279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kolve M, Fischbach W, Greiner A, Wilms K. Differences in endoscopic and clinicopathological features of primary and secondary gastric non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. German gastrointestinal lymphoma study group. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49(3 Pt 1):307–315. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(99)70006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zullo A, Hassan C, Andriani A, et al. Primary low-grade and high-grade gastric MALT-lymphoma presentation. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:340–344. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181b4b1ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akaza K, Motoori T, Nakamura S, et al. Clinicopathologic study of primary gastric lymphoma of B cell phenotype with special reference to low-grade B cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue among the Japanese. Pathol Int. 1995;45:832–845. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1995.tb03403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirose Y, Kaida H, Ishibashi M, et al. Comparison between endoscopic macroscopic classification and F-18 FDG PET findings in gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma patients. Clin Nucl Med. 2012;37:152–157. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e3182393580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nonaka K, Ohata K, Matsuhashi N, et al. Is narrow-band imaging useful for histological evaluation of gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma after treatment? Dig Endosc. 2014;26:358–364. doi: 10.1111/den.12169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Musshoff K. Clinical staging classification of non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas (author’s transl) Strahlentherapie. 1977;153:218–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Copie-Bergman C, Gaulard P, Lavergne-Slove A, et al. Proposal for a new histological grading system for post-treatment evaluation of gastric MALT lymphoma. Gut. 2003;52:1656. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.11.1656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wotherspoon AC, Doglioni C, Diss TC, et al. Regression of primary low-grade B-cell gastric lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Lancet. 1993;342:575–577. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91409-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yokoi T, Nakamura T, Kasugai K, et al. Primary low-grade gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma with polypoid appearance. Polypoid gastric MALT lymphoma: a clinicopathologic study of eight cases. Pathol Int. 1999;49:702–709. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1827.1999.00935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]