Abstract

Twenty-seven subjects with squamous cell cancer of the head and neck received the neoadjuvant IRX-2 immunotherapy regimen prior to surgery in a Phase 2 trial. Pretreatment tumor biopsies were compared with the primary tumor surgical specimens for lymphocyte infiltration, necrosis and fibrosis, using hematoxylin and eosin stain and immunohistochemistry in 25 subjects. Sections were examined by three pathologists. Relative to pretreatment biopsies, increases in lymphocyte infiltration (LI) were seen using H and E or immunohistochemistry. CD3+ CD4+ T cells and CD20+ B cells were primarily found in the peritumoral stroma and CD3+ CD8+ T cells and CD68+ macrophages were mainly intratumoral. LI in the surgical specimens were associated with reductions in the primary tumor size. Improved survival at 5 years was correlated with high overall LI in the tumor specimens. Neoadjuvant IRX-2 immunotherapy regimen may restore immune responsiveness presumably by mobilizing tumor infiltrating effector lymphocytes and macrophages into the tumor.

Keywords: Lymphocytes, Monocytes, Macrophages, IRX-2, Dendritic cells, Cytokines

Background

Squamous cell cancers of the head and neck (HNSCC) are difficult to treat due to a surgically challenging anatomical location, behavioral and nutritional factors, radio/chemotherapy resistance, apparent lack of tumor immunogenicity and profound immunologic perturbations in the host. HNSCC were long considered to be unlikely candidates for immunotherapy. However, developments over the last 20 years have changed this perception, and a number of new immunotherapeutic approaches are being evaluated, including anti-tumor vaccines [1–6]. Although more than 1,600 tumor-associated candidate antigens are known, major challenges remain in overcoming not only the selection of tumor antigen and vaccine formulation but a variety of immunologic disturbances existing in HNSCC patients and involving tumor-derived immunosuppressive factors, host-derived suppressor cells, defective antigen processing cells, and functionally impaired T cells [3, 6–9]. The challenge in HNSCC is to overcome tumor- or host-derived immunosuppression and simultaneously restore or enhance anti-tumor immunity.

IRX-2 was selected for the evaluation in immunotherapy of HNSCC based on over 20 years of work studying the immunopharmacologies of many agents both in vitro and in vivo in mouse models aiming at reversing cellular immune deficiencies. These early studies have been reviewed [10, 11]. Of primary importance were the observations of the Turin group of investigators [12] who treated HNSCC patients with perilymphatic injections of a natural cytokine mixture rich in interleukin 2 (IL-2). They observed several complete and partial but transitory clinical responses [12]. Subsequent studies with recombinant IL-2 (rIL-2) failed to reproduce these early findings [13]. Cortesina et al. [11, 12] showed improved results using low dose IL-2, and these results suggested that a naturally derived mixture of human cytokines (NCM) in conjunction with a regimen designed to enhance the immunomodulatory activity of the cytokines might be more effective than rIL-2. Subsequently, a multidrug regimen was designed that included a pretreatment infusion with a non-cytotoxic dose of cyclophosphamide (CY), concomitant indomethacin (INDO) and zinc plus multi-vitamins. The rationale for this regimen was based upon the reported effects of CY on suppressor T cells [14]; of INDO, a known cyclooxygenase inhibitor of prostaglandin synthesis by suppressor monocyte/macrophages [15]; and of zinc supplementation in restoring zinc deficiency that is prevalent in HNSCC and is associated with cellular immune defects [16, 17].

Initially, in an investigator-initiated study using a natural cytokine mixture (NCM) with the regimen of CY + INDO + Zinc, 2/3 subjects with recurrent disease had partial clinical responses and one previously untreated subject had a partial response prior to surgery [18]. Subsequently, a cGMP biologic agent designated IRX-2, in combination with the above-described regimen, was explored under corporate sponsorship in the US. A Phase I clinical trial was opened in 2003 and a multicenter Phase 2 trial was recently completed, and results for both studies published [19, 20].

This manuscript details immunologic findings in 25 evaluable subjects in the IRX-2 Phase 2 study. Since lymphocyte infiltration has been associated with good outcomes for subjects with HNSCC and other solid malignancies especially in the context of immunotherapy [21–27], a histological evaluation of both pretreatment biopsy samples and post-treatment surgical samples of the tumors was undertaken. Findings were correlated with clinical tumor reduction prior to surgery and overall survival.

Materials and methods

Phase 2 clinical study

Patients with surgically resectable, potentially curable but previously untreated HNSCC signed a consent form and were enrolled in a multi-center phase 2 clinical study of IRX-2 (IRX-2 2005-A). The details of the study design and the clinical results of the study were previously published [20]. A total of 27 subjects were enrolled by 12 of 16 participating investigators (15 study centers in the United States and one center in Mexico). Subjects received a non-cytotoxic dose of cyclophosphamide 3 days before initiating 10 days of peri-lymphatic IRX-2 therapy. Subjects also received 21 days of INDO and zinc supplements prior to surgical resection. All 27 subjects were treated with the IRX-2 regimen and had planned surgery. One subject refused the required total glossectomy and therefore, only 26 subjects had complete tumor resection. Table 1 presents a summary of the clinical characteristics of the subjects treated in this trial. Data on the HPV status of the subjects are not shown, because at the time of design and subsequent execution of the study, the relationship between HPV and response to therapy and survival after surgery in HNSCC subjects was controversial and HPV data were not collected [27]. In addition, suitable specimens for retrospective testing were not available on all enrolled subjects. The table indicates that 30% of the subjects had oropharynx as the site of the disease and since this population is believed to be the most likely to be HPV positive (typically < 40%), the influence of HPV in the study is most likely modest at best.

Table 1.

IRX-2 phase 2 trial characteristics of study population (n = 27)

| Characteristic | Number/percentage |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Years (mean) | 57.4 years old (36 min/79 max) |

| Age > 65 Years | 24 (88.9%) |

| 65 ≤ Age < 75 Years | 2 (7.4%) |

| 75 Years ≤ Age | 1 (3.7%) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 74.1% |

| Female | 25.9% |

| Racial or ethnic group | |

| Caucasian/White | 85.2% |

| Black/African American | 3.7% |

| American Indian/Alaska Native/Pacific Islander | 3.7% |

| Other | 7.4% |

| Karnofsky performance status | |

| 90 or 100 | 88.9% |

| 70 or 80 | 11.1% |

| Site of disease | |

| Oral cavity | 55.6% |

| Oropharynx | 29.6% |

| Larynx | 11.1% |

| Hypopharynx | 3.7% |

| T stage | |

| TX, T0, T1 | 1 (3.7%) |

| T2 | 15 (55.6%) |

| T3 | 6 (22.2%) |

| T4a | 5 (18.5%) |

| N Stage | |

| N0 | 5 (18.5%) |

| N1 | 8 (29.6%) |

| N2a | 1 (3.7%) |

| N2b | 7 (25.9%) |

| N2c | 6 (22.2%) |

| N3 | 0 (0.0%) |

| Stage of disease | |

| I | 0 (0%) |

| II | 11.1% |

| III | 29.6% |

| IVA | 59.3% |

| IVB | 0 (0%) |

| Differentiation of SCC tumor | |

| Low grade | 14.8% |

| Intermediate grade | 51.9% |

| High grade | 14.8% |

| Unknown | 18.5% |

Histology

Slide preparation

Sites participating in IRX-2 2005-A submitted one paraffin embedded biopsy block and one representative tumor resection block, chosen by the site pathologist according to standardized tissue block selection guidelines on all consented and enrolled subjects. Blocks were shipped to PhenoPath Laboratories (Seattle, WA), where sections were cut from the paraffin blocks to perform hematoxylin and eosin stain (H&E) and immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining. Efforts were made to minimize site-to-site variations in tissue handling by providing guidelines for fixing and processing the tissues. The time between tissue collection and placement in formalin was minimized. The tissue samples were trimmed to 4 mm thickness and fit into the cassette with at least a 1 mm space on all sides. Cassettes were filled with 10% neutral buffered formalin to fix the tissue sample. The volume of fixative solution was 15–20 times greater than the volume of the tissue.

If release and shipping of tissue blocks were not possible, sites were instructed to prepare unstained slides by cutting 4 μm sections onto charged glass slides (Fisherbrand Superfrost Plus, Catalogue #12-550-15 or equivalent). Slides were air dried and not baked. Sites provided 10 unstained sections per block. Slides were immediately shipped in the provided PhenoBox with completed Material Transfer Form.

Immunohistochemistry

Standard protocols for immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining were followed using sections from blocks similar to those used in the H&E analysis. Heat-Induced Epitope Retrieval (HIER) was performed using buffers custom selected for each of the antibodies. The antibodies (Abs) used for the IHC studies included the following: anti-CD3 (T cells; BD Biosciences clone SP34 at 1/500), anti-CD20 (B cells; DAKO clone L26 at 1/250), anti-CD68 (Macrophages; DAKO Clone KPI at 1/2000) anti-CD8 (cytotoxic T cells; DAKO clone CD8 144B at 1/100) and anti-CD4 (helper T cells Vector Clone 1F6 at 1/5) abs. Human tonsil tissue was used as a positive control with each run for all antibodies. Irrelevant antibodies served as the controls for each other. Only the surgical samples were stained for subsets of CD3+ cells (CD4+ and CD8+) primarily due to insufficient amounts of biopsy material. Additional lymphocyte subsets were not evaluated either due to a lack of adequate reagents at the time of staining (i.e., Tregs), the lack of appreciation of their biologic reference at the time (i.e., Th17), or the statistical concerns about the evaluation of large numbers of variables in relatively small numbers of subjects (n = 25) [9, 28, 29].

Histological evaluation

Blinding

The complete set of H&E and IHC study slides was randomly sorted and re-numbered so that individual subject biopsy and surgery specimens were not obvious to the reviewer (“random slides”).

Assessments

Three pathologists participated in this study. All received the same set of slides, and their evaluations were performed independently at their location. H&E sections were read by three pathologists but IHC were read by only two of the pathologists. Thus for the majority of the subjects, there were 5 totally independent reads that could be evaluated either separately or as averages. Prior to scoring, an assessment of the overall presence of the cells of interest across the entire specimen was made in order to identify representative areas of tumor on the slide for quantitative evaluation such that biopsy and surgical specimens were both representative of the overall tumor-stromal interface in which the assessment of tumor histology was made. A second assessment was made to more precisely quantitate the histological assessment using a visual analog scale (VAS) provided to the pathologist (see below). When evaluating the data for changes between biopsy and surgery after treatment, especially with respect to the comparison of H&E with IHC assessment, subjects who did not have specimens for both were eliminated from the analysis.

Visual analog scale

Immunologic response features were extracted and quantified using a VAS of 0–100 mm to provide for a more continuous variable than the 0–4+ scale that is often used to assess histological responses. The VAS provides data that are suited to statistical analysis. The scoring was such that 100 represented the maximum for any sample and 0 represented the lack of any parameter of interest. Observations of the samples by the pathologists were made on the VAS case report forms by placing a vertical line on the VAS line indicating their observations between 0 and 100 or their “score” for each feature. The VAS marking was independently measured. The “score” was recorded on the VAS CRF form. All measurements were quality controlled by confirming that the data on the VAS sheet were accurately transcribed. The “scores” were then double data entered and checked for discrepancies. Photographs of surgical specimens from subjects in the study are presented in Figs. 1 and 2 in order to provide examples of the range of VAS scores for lymphocyte infiltration for both H&E and IHC.

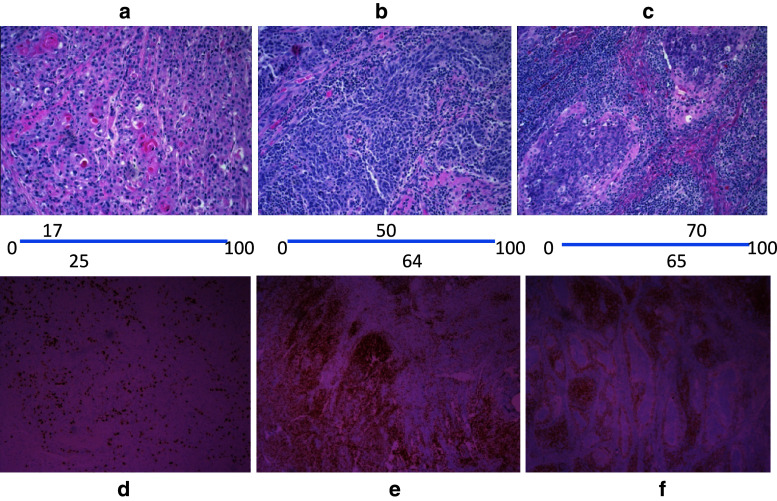

Fig. 1.

Relationship of VAS scoring for H&E lymphocyte infiltration and CD3± cells by immunohistochemistry. Photographs of three different surgical specimens stained with H&E or with IHC for CD3+ cells are shown with their corresponding VAS scores. The H&E sections (a, b, c) have their VAS scores listed below the picture and placed on the position of the VAS line that the pathologist would have made on the VAS scoring line. The VAS scores presented are the average of either three pathologists (H&E) or two pathologists (IHC). The VAS scores for the IHC staining of CD3+ lymphocytes are presented above the three matched sections (d, e, f). In the H&E sections, the small dark blue nuclei of the lymphocytes should be distinguished from the small dark nuclei with surrounding pink cytoplasm of the tumor cells. The intense brown/orange staining for CD3+ cells in e and f is readily contrasted to the few such positive cells in d. Enhanced fibrosis and necrosis can also be seen in sample c as compared to sample a. Sample b is intermediate in scoring

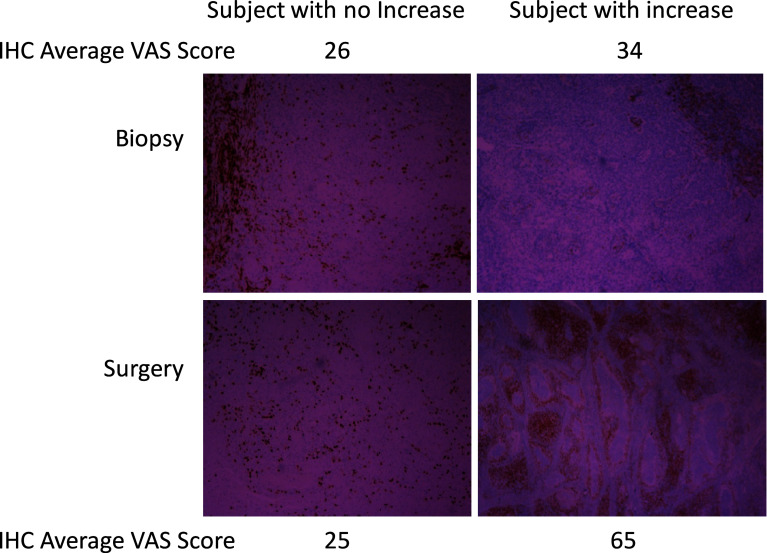

Fig. 2.

Relationship of VAS scores and CD3± IHC in comparing initial pretreatment biopsies with surgical specimens. Biopsy and surgical specimens from subjects treated with IRX-2 immunotherapy regimen were stained for CD3+ positive cells. The photographs illustrate a patient that has minimal increase in CD3+ cells in the surgical specimen compared to the biopsy and a subject with a more significant increase in CD3+ cells. Note that although tumor histology cannot be readily assessed in IHC, both subjects had CD3+ cells located predominantly on “margins” in the biopsy sample while the subject with the increase in CD3+ cells in the surgical specimen had an enhanced intratumoral infiltration

The prospectively defined immune response features were designed to capture the spectrum of immune response in HNSCC. Given that lymphocytes are thought to play a major role in killing tumor cells, the features extracted related to the characterization of the infiltrate and its location. Additional features related to the tumor were assessed as fibrosis and tumor necrosis.

Determination of Peritumoral vs. Intratumoral Infiltrates

It was prospectively defined that the reader would read the slide under low power to evaluate the overall size of the specimen, the area representing tumor and its orientation to identify the leading edge and define that area as the tumor’s peripheral area (peritumoral). The area opposite the center of the body of the tumor or at the periphery of the tumor was classified as peritumoral. For each of the markers, an evaluation was performed to determine the degree to which each of the markers was located in the peri- or intra-tumoral areas. This degree of location was marked on the VAS scoring sheet such that a low score represented that the majority of the cells were outside the tumor (peritumoral) and a high score represented more cells inside the tumor (intratumoral).

Statistical analysis methodology

Exploratory statistical analyses were performed to assess the relationship of the histological assessments to measures of biologic and clinical activity including overall survival and change in the longest diameter (LD) of the primary tumor from time of biopsy to surgery (approximately 21 days) as determined by a central-independent radiologist. Initial statistical evaluation compared the averages of histological assessments for biopsy to surgical specimen. The data were graphically displayed using box-and-whisker plots. The box-and-whisker plot provided a visual representation of the median, the quartiles and the smallest and greatest values in the distribution. The changes from biopsy to surgery were analyzed with one-sample t-tests. The purpose of these analyses was to identify changes that might be of potential clinical interest.

The correlation between histological assessments and change in tumor size was assessed using Pearson and Spearman rank correlations. The correlation of histological assessments with overall survival was assessed using univariate Cox proportional hazards regression models. Multiple Cox proportional hazards regression with stepwise variable selection was then used to identify the histological assessments that had the greatest association with overall survival. Cox models were also used to determine thresholds of the histological assessments that identified subsets of subjects with better survival prognosis. Kaplan–Meyer plots were used to demonstrate relationship between overall survival and the histological assessments.

Results

There is a direct relationship between the values scored on the VAS for both the H&E and IHC. Figure 1 presents examples of three surgical specimens from subjects treated with the IRX-2 immunotherapy regimen prior to their surgery. They were selected to demonstrate the relationship of VAS scores with the H&E and IHC. Surgical resections reflecting three different VAS scores were selected as examples. The two different pathologic assessments are complementary. The H&E assessment provides a visual view of the structure of the tumor specimen such that in addition to lymphocyte infiltration (LI), fibrosis and necrosis can also be scored. A drawback of the H&E, however, is that distinguishing the tumor (small blue nuclei with light pink cytoplasm) from lymphocytes (blue nucleus with little cytoplasm) is not always obvious. On the other hand, due to the specificity of the antibody, the IHC for the matching tumor can be readily scored for the presence of lymphocytes, although identifying the architecture of the surrounding tissue is more difficult due to the lack of a useful counter stain. Location can also be more accurately assessed on IHC stained samples when the H&E for the same section is also available. Figure 2 displays representative photographs of the biopsy and corresponding surgical specimens from two subjects treated with the IRX-2 immunotherapy regimen including one that had no significant increase in CD3+ cells and one subject that had an increase. Again, a direct relationship between the VAS scores and the visual changes seen in the slides is demonstrated.

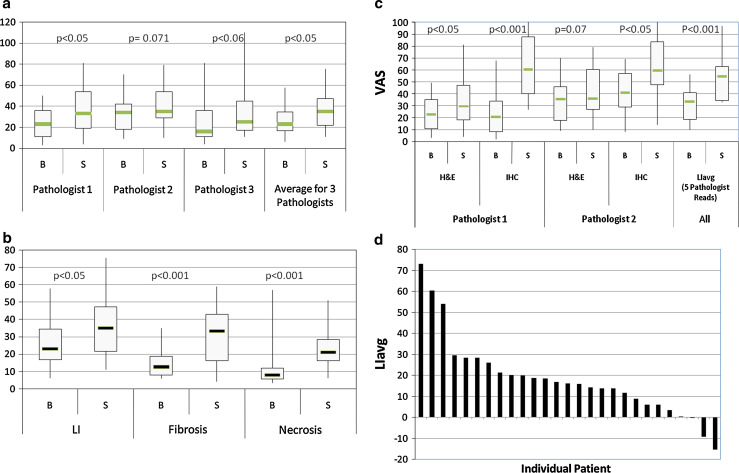

Three independent pathologists used H&E stained slides and assessed the lymphoid infiltration (LI) in the specimens using the VAS as described in the methods. All three pathologists observed an increase in lymphoid infiltration following IRX-2 treatment in the majority of subjects (Figs. 1, 3a–d). The average range of variation on a case-by-case basis was about 10 mm on a VAS of 100 mm. The pathologists were blinded to the subject’s name and clinical outcomes. Figure 3a shows the comparison of biopsy and surgery reads for lymphoid infiltration as the individual average scores of three pathologists who were given the H&E stained slides for the evaluation along with the average scores of the three. As described in the methods, scoring was based on the infiltration such that the pretreatment biopsy and post-treatment surgical samples were scored similarly without regard for the size or section of the tumor. Figure 3b shows the average of the three H&E reads of the blinded specimens for lymphocyte infiltration (LI) as well as the immunotherapy-related changes in fibrosis and necrosis. IHC stained slides were also used by two pathologists to assess LI of specific leukocyte subsets, using the VAS. Figure 3c compares IHC assessment of LI (using VAS for CD3+ T cells plus CD20+ B cells) with H&E assessments for the two blinded readers who reviewed both the H&E and IHC slides. The graph clearly shows the advantage of using IHC for assessing LI since the immunoperoxidase reaction greatly facilitates the ability to identify tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) and enhances the perception of differences between pre- and post-IRX-2 immunotherapy. In addition, Fig. 3c shows results for the LIavg value calculated as the average of the three histological and two immunohistochemical reads available for the subjects. Figure 3d presents the change in lymphocyte infiltration for the individual subjects calculated as the change in LIavg (surgical specimen value minus biopsy value). The majority of subjects were observed to have an increase after 10 days of IRX-2 therapy (20 positive out of 25 (80% P < 0.001 using Student’s t-test)).

Fig. 3.

Assessment of histological features in biopsy and surgical tumor specimens. Specimens were stained by H&E or IHC. The VAS scores presented are the average of either three pathologists (H&E) or two pathologists (IHC). All subjects were treated with the IRX-2 immunotherapy regimen prior to surgical removal of the tumor. Lymphocyte Infiltration was assessed using a VAS of 0–100 mm where 100 represented the maximum infiltration seen in the specimens. The changes in each assessment were analyzed using one-sample t-tests. The graphs represent the change (Surgery [S] − Biopsy [B]) for the LIavg for individual subjects, sorted based on the magnitude of the change. a Lymphocyte infiltration for H&E-stained specimens by VAS scores are shown by box-and-whisker plots for each of the three pathologists’ reads as well as the average calculated using the value of the three pathologists for each subject. b Lymphocyte infiltration, fibrosis and necrosis as read by three pathologists on H&E specimens. c Lymphocyte infiltration assessed by two pathologists using both H&E stained and IHC stained specimens. LI for the IHC specimens was calculated by adding the VAS score for CD3+ and CD20+ cell infiltration. Also shown on the graph is the Lymphocyte Infiltration Average (LIavg) that was defined as the average VAS Score for all 5 reads (3 H&E and 2 IHC). d Change in LIavg for individual patients

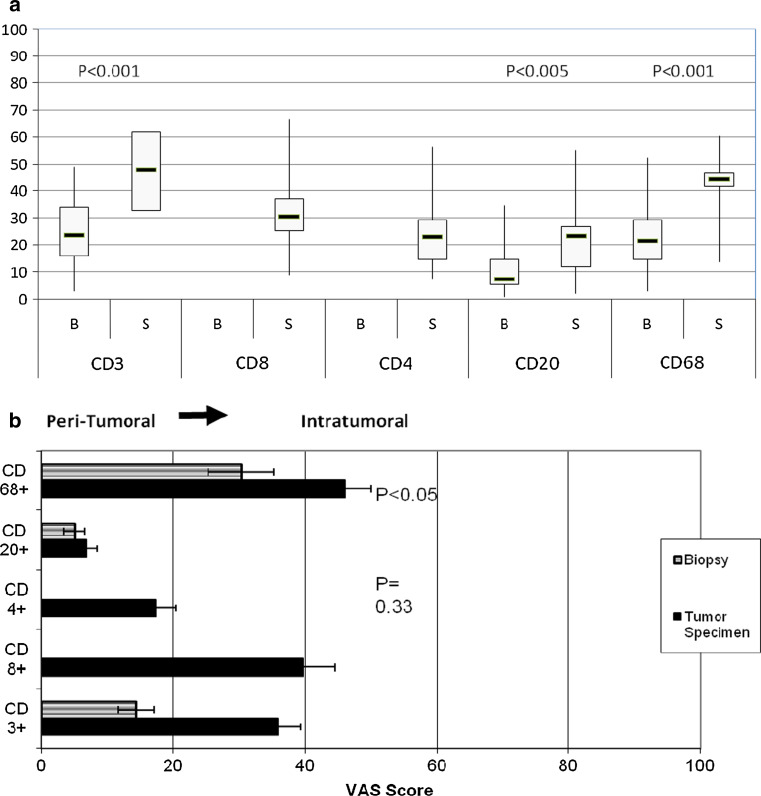

Increases in CD3+, CD20+ and CD68+ cells were observed in the surgical tumor specimen compared to pretreatment biopsies (Fig. 4a). We only evaluated CD4+ and CD8+ subsets in the resected tumors due to limited tissue availability in the biopsy sample. Since the location of leukocyte subsets could be readily identified using IHC, the two pathologists also assessed whether the various cell populations were predominately in the peritumoral region (left side of the graph) or intratumoral region (right side of the graph in Fig. 4b). Subjects treated with IRX-2 had the increase in overall CD3+ T cells, in the intratumoral region. The CD4+ cells were mainly localized in the peritumoral areas, while the CD8+ T cells were mainly in the intratumoral regions. The increases in the CD20+ B cells were mainly peritumoral, while increases in the CD68+ macrophages were mainly intratumoral.

Fig. 4.

Lymphocyte infiltration subsets defined as the average VAS score by two pathologists. a The graph displays the VAS scores for biopsy versus surgery for subjects with IHC stained slides (n = 21). a The extent of leukocyte infiltration in the surgical samples. Biopsy samples were not stained for CD4+ and CD8+. The change from biopsy to surgery was analyzed using a one-sample t-test. b Location of infiltrating lymphocytes in primary tumor (surgical sample). Location in the tumor of the lymphocyte infiltration was defined using a 0–100 VAS scale that was from peripheral (peritumoral (0) or far left) or intratumoral (100 for far right). The graph displays the average VAS scores for biopsy versus surgery in subjects with IHC stained slides. (n = 21)

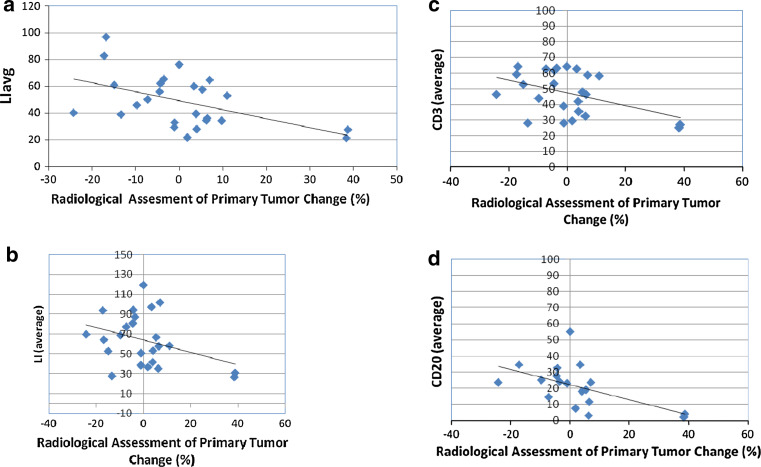

As shown in Table 2 and Fig. 5, the correlation of radiologic tumor size change with histological assessment was evaluated using both Pearson and Spearman rank correlations. As shown in Fig. 5, high LIavg values at surgery were associated with decreases in size of the primary tumor. Of note was the observation that the two subjects, who had increases in tumor following IRX-2 immunotherapy, also had the least lymphocyte infiltration in the surgical specimen (Fig. 5). As shown in Fig. 5b, the LI for IHC at surgery also had a negative correlation with tumor change that is high LI values were associated with decreases in tumor size, when assessed as the sum of CD3+ and CD20+ lymphocytes. The CD3+ and CD20+ lymphocyte subsets in the surgical specimen also had negative correlations with change in tumor size (Fig. 5c, d) with the CD20+ having a generally higher correlation (Table 1). The correlation of change in tumor size with change in necrosis was also negative; there was little apparent correlation of change in tumor size with CD68, CD8 and CD4 at either biopsy or surgery.

Table 2.

Correlation of histological assessments with radiologic tumor reduction after 10 days of IRX-2

| Description | N | Spearman rank correlation | P value (Spearman) | Pearson correlation | P value (Pearson) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LI avg at biopsy | 25 | −0.36 | 0.655 | −0.141 | 0.501 |

| LI avg at surgery | 25 | −0.473 | 0.017 | −0.500 | 0.011 |

| LI avg change | 25 | −0.259 | 0.211 | −0.384 | 0.058 |

| H&E | |||||

| LI VAS avg by H&E at biopsy | 25 | −0.094 | 0.655 | −0.141 | 0.501 |

| LI VAS avg by H&E at surgery | 25 | −0.252 | 0.224 | −0.381 | 0.060 |

| LI VAS avg by H&E change | 25 | −0.084 | 0.689 | −0.236 | 0.257 |

| Necrosis at biopsy | 25 | 0.305 | 0.138 | 0.553 | 0.004 |

| Necrosis at surgery | 25 | −0.218 | 0.295 | −0.251 | 0.226 |

| Necrosis change | 25 | −0.485 | 0.014 | −0.624 | 0.001 |

| IHC | |||||

| LI CD3 +CD20 at biopsy | 23 | 0.041 | 0.854 | −0.074 | 0.728 |

| LI CD3 +CD20 at surgery | 24 | −0.409 | 0.047 | −0.502 | 0.012 |

| LI CD3 +CD20 change | 23 | −0.392 | 0.064 | −0.401 | 0.058 |

| CD3 at biopsy | 24 | −0.056 | 0.798 | −0.133 | 0.536 |

| CD3 at surgery | 24 | −0.357 | 0.087 | −0.438 | 0.032 |

| CD3 change | 24 | −0.249 | 0.240 | −0.334 | 0.111 |

| CD20 at biopsy | 23 | 0.109 | 0.620 | −0.449 | 0.032 |

| CD20 at surgery | 24 | −0.519 | 0.009 | −0.518 | 0.010 |

| CD20 change | 23 | −0.659 | 0.001 | −0.449 | 0.032 |

Bold data presented on graphs in Fig. 3 to confirm a biologically relevant correlation for the samples with P < 0.05 by Pearson correlation. Additional data provided for completeness even though P > 0.05

Fig. 5.

Centrally reviewed radiologic change in primary tumor following the IRX-2 immunotherapy regimen versus lymphocyte infiltration. a The change in tumor size following treatment with IRX-2 immunotherapy regimen was defined by radiologic assessment and is plotted against the lymphocyte infiltration in the surgical specimen defined by the LIavg. The LIavg in the tumor specimen correlated with percent change in tumor size (P < 0.05, Pearson correlation). Also plotted b, c, d are the results for LI by IHC (CD3+ and CD20+) average and for CD3+ average and CD20+ average. The x-axis displays percent tumor change and the y-axis displays the average value for tumor specimen of subjects with IHC-stained slides. All 3 IHC assessments were correlated with change in tumor size (P < 0.05, Pearson correlation, see Table 2)

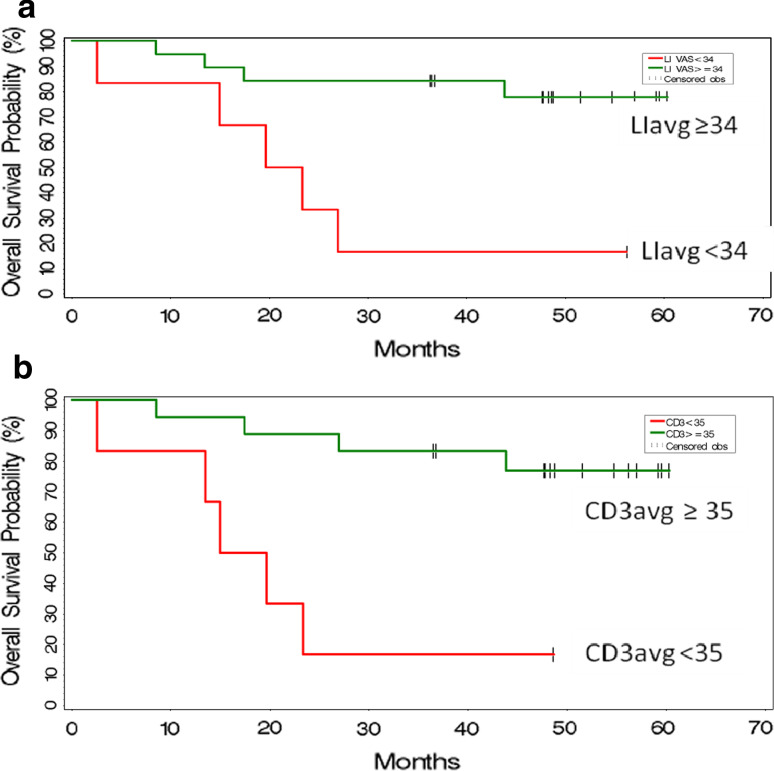

A majority (17/26 = 65%) of subjects treated with neoadjuvant IRX-2 immunotherapy were alive at the 5-year assessment visit when the trial was closed. The association of overall survival with histological assessments was assessed using Cox proportional hazards regression models (Table 3). When the parameters with greatest association with survival (P value ≤ 0.10) were further evaluated using multiple Cox regression with stepwise variable selection, CD3+ lymphocyte infiltration in the surgical specimen was shown to have the strongest association with overall survival; however this variable is highly correlated with LIavg at surgery and LI by IHC at surgery and biopsy. Figure 6 plots the Kaplan–Meier estimates of overall survival estimates for subjects with high vs. low LIavg and high vs. low CD3+ lymphocytes at surgery, both of which had P values < 0.05 in the Cox regressions.

Table 3.

Univariate Cox Proportional Hazards Regression Analysis for Overall Survival

| Variable | N | Time point | P value (Chi-square) | Hazard ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD3 | 24 | Biopsy | 0.046 | 0.936 |

| 24 | Surgery | 0.008 | 0.921 | |

| 24 | Change | 0.328 | 0.975 | |

| LIavg | 25 | Biopsy | 0.156 | 0.961 |

| 25 | Surgery | 0.039 | 0.980 | |

| 25 | Change | 0.299 | 0.990 | |

| LI(CD3–CD20) | 23 | Biopsy | 0.038 | 0.954 |

| 24 | Surgery | 0.038 | 0.969 | |

| 23 | Change | 0.678 | 0.995 | |

| LI H&E | 25 | Biopsy | 0.528 | 0.983 |

| 25 | Surgery | 0.029 | 0.946 | |

| 25 | Change | 0.115 | 0.965 | |

| Fibrosis | 25 | Biopsy | 0.527 | 1.026 |

| 25 | Surgery | 0.073 | 1.042 | |

| 25 | Change | 0.077 | 1.046 | |

| Necrosis | 25 | Biopsy | 0.015 | 1.112 |

| 25 | Surgery | 0.164 | 1.038 | |

| 25 | Change | 0.656 | 0.986 | |

| % Tumor | 24 | Biopsy | 0.801 | 0.989 |

| 24 | Surgery | 0.891 | 1.005 | |

| 24 | Change | 0.714 | 1.014 |

Bold represent values assessed in multiple Cox regression analysis. Additional data provided for completeness even though P > 0.05

Fig. 6.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of overall survival by intensity of lymphocyte infiltration assessed using H&E or IHC of the resected primary tumor after IRX-2 immunotherapy regimen. Kaplan–Meier estimates of overall survival for subjects in the Phase 2 trial are presented on the graph as a function of high- and low lymphocyte infiltration in the surgical specimens after the IRX-2 immunotherapy regimen. The upper graph is for LIavg and the lower graph is for CD3+ T-cell average. The cut-offs selected for identifying the 2 subsets of subjects are indicated in the legends for the graphs. The number of subjects in each are as follows: LIavg n = 18 best survival versus n = 7 worst survival; CD3+ n = 18 best survival and n = 6 worst survival. a LIavg versus Survival (P < 0.05). b LI CD3 versus Survival (P < 0.01)

Discussion

Our data conclusively demonstrate that a short neo-adjuvant course of the IRX-2 immunotherapy regimen is associated with an enhanced infiltrate of leukocytes into the tumors of patients with HNSCC who were felt to be good candidates for potentially curative resection. These data also clearly demonstrate that the enhanced infiltration of lymphocytes was associated with radiologic reductions in tumor size and with improvement in overall survival. With respect to the patient population, although the HPV status was not assessed, it has recently been suggested that there may be a modest correlation with HPV status and survival. As shown in Table 2, only 30% of the subjects in this study had oropharynx cancer and of those patients only 40% would be predicted to be HPV positive. In addition, when we compared the CD3+ VAS scores of the oropharynx to the other locations, there was no difference in the VAS score at surgery, again suggesting that HPV played a minimal role in these outcomes. Because this was not a randomized controlled trial, we cannot be certain whether IRX-2 is responsible for the enhanced lymphocyte infiltration and outcome in some patients or whether we are identifying patients with a more favorable endogenous immune response to their tumors. The increase in the infiltrations in the resected tumor specimens after the IRX-2 regimen compared to the pretreatment biopsy samples is suggestive of an IRX-2-mediated effect.

The validity of the observed changes in lymphocyte infiltration analyses was confirmed using the observations of three pathologists who were given the same random specimens for the evaluation. To enhance the evaluation of consistency among readers, scores were generated using a VAS to better quantitate the observations between weak (0) and intense (100) lymphocytic infiltration. The correlation among the three observers who read H&E stained specimens was high. Increases in leukocyte infiltration were seen in the majority of patients by all three pathologists. The use of IHC enhanced the detection of differences in LI assessed in the biopsy and the surgical specimen. It also provided an opportunity to define a subset of lymphocytes infiltrating the tumor. Increases in CD3+ T cells were observed in 80% of subjects. Increases in CD20+ B cells and CD68+ macrophages were also noted. When the location of the increased T cells in the surgical specimen was further evaluated by subsets, the increases in CD4+ T cells were both peritumoral and intratumoral, while CD8+ T cells predominated intratumorally. The mean ratio of CD4+ to CD8+ was 0.71, indicating a preferential CD8+ T-cell response. Others have observed CD4+ lymphocytes mostly peritumorally and a predominance of CD8+ cells in the tumor, and an overall CD4:CD8 ratio of > 1:1 [22–24]. In the literature [22–24], a CD4:CD8 ratio less than 1 yields a favorable prognosis, and B cells are rarely seen [22]. We did not evaluate the Treg or other lymphocyte subsets (such as TH17 cells) that have recently been shown to play important roles in the immune response to cancer [9, 28, 29].

The observed changes in lymphoid infiltrates were associated with changes in the resected tumor samples including fibrosis and necrosis. In the pretreatment biopsy samples, and as reported in the literature, these characteristics are found in approximately 25% of patients who tend to have improved outcome [21–24]. Increased LIavg (surgical section versus pretreatment biopsy) after the IRX-2 regimen was seen in all but three patients (22/25 or 88%).

The increase in CD3+ and CD20+ lymphocytes in the tumor was expected and is consistent with the hypothesis that infiltration of tumors with T cells and B cells is associated with a good prognosis [21–24]. On the other hand, the levels of CD68+ cells in tumors (i.e., tumor-associated macrophages; TAMs) and the relationship with prognosis remain controversial [30–36]. This is due to conflicting observations with respect to the role of tumoricidal macrophages (so called T1 polarized) and tumor suppressing macrophages (so called T2 polarized) in tumor regression/progression. There is also the controversy with respect to whether location of the CD68+ cells is favorable (i.e., intratumoral) or unfavorable (extra-tumoral). Since there are no cell surface markers that distinguish between the two vastly different macrophage populations, only studies evaluating biological function or gene expression are likely to yield useful information. An important component of this polarization is the plasticity of the cells which leads to the hypothesis that an increase in TH1 character of the tumor may shift the macrophage phenotype to one for tumor destruction rather than tumor enhancement. We hypothesize that IRX-2 treatment influenced the ratios of tumoricidal and suppressing macrophages such that in patients with decrease in tumor and enhanced survival, the ratio was favorable for tumoricidal activity as compared to patients with a less favorable outcome. Further analysis of macrophage subsets and function in subsequent trials will be important.

When histological assessments were tested for correlations with radiologic change in primary tumor size following IRX-2 treatment, lymphocyte infiltration was higher in those subjects whose tumor decreased in size after IRX-2 immunotherapy. In an attempt to relate the IRX-2 immunotherapy regimen associated increases in various sub-sets of lymphocytes to clinical findings, we compared CD3+ CD20+ (total), CD3+ (T), CD4+ (T), CD8+ (T), CD20+ (B) and CD68+ (tumor-associated macrophage) levels with radiologic change in size of the primary tumor. Although all populations tended to contribute to the correlation of LI as defined by IHC with radiologic changes in tumor, CD20+ B cells in the tumor, although the lowest in numbers, had the highest correlation (higher CD20+ (B) associated with decreases in tumor size) with change in tumor size (Table 1). With respect to overall survival, this study extended the initial observation reported in our previous manuscript describing the safety and clinical observations of the Phase 2 trial. In that report, H&E specimens were read by a single observer and the average LI of the entire population in the tumors at surgery as defined by the VAS score was used to define two populations: a high LI group (n = 10) and a low LI group (n = 14). Using a cut-off of 37, two distinct survival curves were demonstrated with the highest VAS scores being associated with the best survival. In the results presented here, multiple readers were used to create average VAS scores, and multivariate analysis was used to determine which variables were associated with survival. As shown in Table 3 and the Kaplan–Meier plots in Fig. 5, the LIavg (3 H&E reads and 2 IHC reads; P = 0.039), CD3+ CD20 (average LI using IHC; P = 0.038) and the CD3avg (2 IHC reads; P = 0.008) in the tumor specimens at surgery were associated with survival. The frequency of CD3+ T lymphocytes in the surgical specimens appeared to be the strongest predictor of survival.

We interpret these observations as a demonstration that the IRX-2 immunotherapy regimen has the potential to enhance survival in these patients likely by enhancing the immune response to the tumor. We have not yet identified the potential tumor antigens that these lymphocytes are directed at. Additional mechanisms may also be elicited by IRX-2 immunotherapy and this broad enhancement of the immune response may make IRX-2 a unique immune modulator when compared to studies where individual cytokines are used to enhance the immune response.

Many studies indicate that lymphocyte infiltration in HNSCC subjects correlates with disease-free survival, locoregional control and/or overall survival [21–26]. The prognostic importance of type, density and location of immune cells infiltrating colorectal cancer was shown by Galon et al. [37] in 415 subjects with colorectal cancer. T-cell infiltration was a statistically significant predictor of survival in multivariate analysis and remained more predictive than standard tumor histopathology. Similarly in head and neck cancer, tumor infiltration has also been shown to be statistically associated with improved outcome [21–24]. We hypothesize that the immunologic changes induced by IRX-2 immunotherapy in the tumors is predictive of improved clinical outcome. The induced changes could also correlate with other assays, including gene expression signatures that have been suggested to predict outcome to various treatments including cancer immunotherapies [37].

The mechanisms responsible for the observed effects of IRX-2 are currently unknown. Potentially, IRX-2 consisting of several cytokines stimulates multiple immune cell types and could be active through several molecular mechanisms. In vitro studies have shown that IRX-2 treatment of dendritic cells results in the up-regulation of markers associated with antigen presentation [38]. IRX-2 also causes an increase in both CD83 protein expression and the percentage of cells expressing CD83, a marker for DC maturation. IRX-2 increases expression of MHC class I and co-stimulatory molecules on DCs. Schilling et al. [39] have recently shown that IRX-2 reverses, in vitro, the DC defects of HNSCC subjects. Kast et al. [40] have shown that whereas Langerhan’s cells infected with the HPV virus do not show evidence of activation, this can be reversed by incubation with IRX-2 (MK personal communication). Also, NCM may reverse the sinus histiocytosis (reduction in size, depletion of T cells and intrasinusoidal accumulation of immature dendritic cells that are FASCIN+ CD68+ CD83− CD86−) seen in draining lymph nodes of HNSCC subjects (Signorelli, Quadrini-unpublished data).

Czystowska et al. [41] have shown that IRX-2 can protect T cells from activation induced cell death. This group used two different models of activation-induced T-cell death including tumor-derived microvesicles expressing Fas ligand. IRX-2-induced cyto-protection was dose- and time dependant. IRX-2 reversed microvesscals (MV) induced inhibition of the PI3 K/Akt pathway. IRX-2 corrected the imbalance of pro- versus anti-apoptotic proteins induced by the microvesicles [42].

Most recently we have shown that IRX-2 induces enhanced T-cell responses when administered with various tumor antigen vaccines [43]. In fact, immune responses to peptides, conjugated peptides, proteins, cellular and viral vaccines have been augmented by combining the vaccine with local IRX-2 administration. This effect is dose dependent and can be seen in T cells removed from draining lymph nodes or the spleen. We speculate that peri-nodal IRX-2 treatment in subjects with head and neck cancer enhances endogenous antigen-specific T-cell responses to the tumor. Antigen-specific immune responses to head and neck tumor antigens will be studied in subsequent clinical trials. In addition, a phase I/II trial of IRX-2 in combination with a peptide vaccine is currently in the planning stages.

The present findings support a novel and fundamentally important hypothesis that IRX-2 administered upstream from lymph nodes regional to head and neck cancer together with CY, INDO and vitamins with zinc can yield tumoral changes indicative of T-cell, B-cell and macrophage invasion and associated tumor necrosis and fibrosis. These changes were rigorously documented histologically and with immunohistochemistry and correlated with radiologic assessments of tumor shrinkage and overall survival. The results may represent an immunization enabled immune activation to, as yet, unidentified endogenous tumor antigens. Based on these observations and the safety profiles from the reported Phase 1 and Phase 2 trials, a randomized controlled trial of IRX-2 immunotherapy in patients with HNSCC is warranted.

References

- 1.Hoffman TK, Bier H, Whiteside TL. Targeting the immune system: novel therapeutic approaches in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2004;53:1055–1067. doi: 10.1007/s00262-004-0530-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whiteside TL. Anti-tumor vaccines in head and neck cancer: targeting immune responses to the tumor. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2007;7:633–642. doi: 10.2174/156800907782418310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferris RL, Whiteside TL, Ferrone S. Immune escape associated with functional defects in antigen-processing machinery in head and neck cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:3890–3895. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agada FO, Alhamarneh O, Stafford ND, et al. Immunotherapy in head and neck cancer: current practice and future possibilities. J Laryngol Onc. 2009;123:19–28. doi: 10.1017/S0022215108003356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dunn G, Oliver KM, Loke D, et al. Dendritic cells in HNSCC: a potential treatment option? (Review) Oncol Reports. 2005;13:3–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kross KW, Heimdal JH, Aarstad HJ. Mononuclear phagocytes in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;267:335–344. doi: 10.1007/s00405-009-1153-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whiteside TL. Immunobiology of head and neck cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2005;24:95–105. doi: 10.1007/s10555-005-5050-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Young RM. Protective mechanisms of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas from immune assault. Head Neck. 2006;28:462–470. doi: 10.1002/hed.20331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duray A, Demoulin S, Hubert P, Delvenne P, Saussez S. Immune suppression in head and neck cancers: a review. Clin Develop Immunology 2010; published on line: 2010 ID 701657 doi 10.1155/2010/701657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Hadden JW. The immunology of head and neck cancer: prospects for immunotherapy. Clin Immunother. 1995;3:362–385. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hadden JW. The immunopharmacology of head and neck cancer: an update. Int J Immunopharmac. 1997;19:629–644. doi: 10.1016/S0192-0561(97)00063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cortesina G, De Stefani A, Giovarelli M, et al. Treatment of recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck with low doses of interleukin-2 injected perilymphatically. Cancer. 1988;62:2482–2485. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19881215)62:12<2482::AID-CNCR2820621205>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cortesina G, De Stefani A, Galeazzi E, et al. Temporary regression of recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck is achieved with a low but not with a high dose of recombinant interleukin 2 injected perilymphatically. Br J Cancer. 1994;69:572–576. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1994.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berd D, Mastrangelo MJ, Engstrom PF, et al. Augmentation of the human immune response by cyclophosphamide. Cancer Res. 1982;42:4862–4866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berlinger NT. Deficient immunity in head and neck cancer due to excessive monocyte production of prostaglandins. Laryngoscope. 1984;94:1407–1411. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198411000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hadden J. The treatment of zinc deficiency as an Immunotherapy. Int J Immunopharmac. 1995;17:697. doi: 10.1016/0192-0561(95)00062-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prasad AS, Beck FW, Snell CD, et al. Zinc in cancer prevention. Nutr Cancer. 2009;61:879–887. doi: 10.1080/01635580903285122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hadden J, Endicott J, Backey P, et al. Interleukins and contrasuppression induce immune regression of head and neck cancer. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1994;120:395–403. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1994.01880280023004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Freeman SM, Barrera JL, Kenady DE, et al (2010) A Phase 1 safety study of an IRX-2 regimen in subjects with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Am J Clin Oncol in press [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Wolf GT, Fee WE, Dolan RW, et al (2011) Novel neoadjuvant immunotherapy regimen safety and survival in head and neck squamous cell cancer. Head Neck. Article first published online: 31 Jan 2011 doi:10.1002/hed.21660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Uppaluri R, Dunn GP, Lewis JS. Focus on TILs: prognostic significance of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in head and neck cancers. Cancer Immunity. 2008;8:16–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Badoual C, Hans S, Rodriguez J, et al. Prognostic value of tumor-infiltrating CD4+ T-cell subpopulations in head and neck cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:465–472. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wolf GT, Hudson JL, Peterson KA, et al. Lymphocyte subpopulations infiltrating squamous carcinomas of the head and neck: correlations with extent of tumor and prognosis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1986;95:142–152. doi: 10.1177/019459988609500203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Snyderman CH, Heo DS, Chen K, et al. T-cell markers in tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes of head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 1989;11:331–336. doi: 10.1002/hed.2880110408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ogino T, Shigyo H, Ishii H, et al. HLA class I antigen down-regulation in primary laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma lesions as a poor prognostic marker. Cancer Res. 2006;66:9281–9289. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meneses A, Verastegui E, Barrera JL, et al. Histologic findings in subjects with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma receiving perilymphatic natural cytokine mixture prior to surgery. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1998;122:447–454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Galon J, Costes A, Cabo F-S, et al. Type, density, and location of immune cells within human colorectal tumors predict clinical outcome. Science. 2006;313:1960–1964. doi: 10.1126/science.1129139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kong CS, Narasimhan B, Cao H, et al. The relationship between human papillomavirus status and other molecular prognostic markers in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. A J Rad Ongol. 2009;74:553–561. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee J-J, Chang Y-L, Lai W-L et al (2010) Increases prevalence of interleukin-17-producing CD4+ tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in human oral squamous cell carcinoma. Head and Neck; published on line: doi:10.1002/hed21607 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Al-Sarireh B, Eremin O. Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMS): disordered function, immune suppression and progressive tumor growth. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 2000;45:1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sica A. Role of tumor-associated macrophages in cancer-related inflammation. Exp Oncol. 2010;32:153–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mantovani A, Sica A, Allvena P, et al. Tumor-associated macrophages and related muyeloid-derived suppressor cells as a paradigm of the diversity of macrophage activation. Human immunol. 2009;70:325–330. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2009.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ohno S, Ohno Y, Suzuki N, et al. Correlation of histological location of tumor associated macrophages with clinicopathological features in endometrial cancer. Anticancer Res. 2004;24:337–3342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Forssell J, Öberg A, Henriksson ML, et al. High macrophage infiltration along the tumor front correlate with improved survival in colon cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1472–1479. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ma J, Liu L, Chel G. The M1 form of tumor-associated macrophages in non-small cell lung cancer is positively associated with survival time. BMC Cancer. 2010;10(1–9):112. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ohri CM, Shikotra A, Green RH, Waller DA, Bradding P. Macrophages within NSCLC tumour islets are predominantly of a cytotoxic M1 phenotype associated with extended survival. Eur Respir J. 2009;33:118–126. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00065708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gajewski TH, Louahed J, Brichard VG. Gene signature in melanoma associated with clinical activity: a potential clue to unlock cancer immunotherapy. Cancer J. 2010;16:399–4703. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e3181eacbd8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Egan JE, Quadrini KJ, Santiago-Schwarz F, et al. IRX-2, a novel in vivo immunotherapeutic, induces maturation and activation of human dendritic cells in vitro. J Immunother. 2007;30:624–633. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3180691593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schilling B, Harasymczuk M, Schuler P, et al (2010) AACR meeting poster. Abstract #244409_1

- 40.Meneses A, Verastegui E, Barrera JL, et al. Lymph node histology in head and neck cancer: impact of immunotherapy with IRX-2. Int Immunopharm. 2003;3(8):1083–1091. doi: 10.1016/S1567-5769(03)00017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Czystowska M, Han J, Szczepanski MJ, et al. IRX-2, a novel immunotherapeutic, protects human T cells from tumor-induced cell death. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16:708–718. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Czystowska M, Szczepanski MJ, Szajnik M, Quadrini et al (2010) Mechanisms of T-cell protection from death by IRX-2: a new immunotherapeutic. Cancer Immunol Immunother. Dec 23. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Naylor PH, Hernandez KE, Nixon AE, et al. IRX-2 increases the T cell-specific immune response to protein/peptide vaccines. Vaccine. 2010;28:7054–7062. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]