Summary

Botswana has experienced a dramatic increase in HIV-related malignancies over the past decade. The BOTSOGO collaboration sought to establish a sustainable partnership with the Botswana oncology community to improve cancer care. This collaboration is anchored by regular tumor boards and on-site visits that have resulted in the introduction of new approaches to treatment and perceived improvements in care, providing one model for partnership between academic oncology centers and high burden countries with limited resources.

Introduction

The global burden of cancer is considerable. The majority of cancer cases and over 70% of cancer deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs)(1–3). Based on current population trends, global cancer mortality is expected to double by the year 2030. In sub-Saharan Africa, the rising epidemic of cancer is coupled with a high prevalence of HIV, presenting unique challenges for patients, health care providers, and local governments.

The nation of Botswana (Figure 1) sits at the crossroads of cancer and HIV. It has one of the most successful HIV treatment programs (4) and now faces a rising burden of malignancies, predominantly among HIV-infected persons on appropriate antiretroviral treatment (ART). Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and Botswana Harvard AIDS Institute, along with the Botswana-University of Pennsylvania Partnership and Baylor College of Medicine, have partnered with the local oncology community and government of Botswana with the goal of addressing this rising burden. Herein, we aim to describe the MGH and Botswana Harvard AIDS Institute efforts as one model of a partnership between academic medical centers and LMICs with limited oncology resources.

Figure 1. Map indicating Gaborone and Francistown, Botswana.

The majority of cancer care is delivered in referral centers in these cities.

Health and Cancer Care in Botswana

At the time of independence in 1966, Botswana was one of the poorest countries in Africa and had very limited healthcare infrastructure. The development of stable democratic governance and the subsequent discovery of mineral wealth have permitted rapid and sustained economic expansion (5). Botswana is now among the most affluent countries in Africa and has invested heavily in healthcare with construction of over 300 health clinics and dozens of regional hospitals to care for a population of 2 million persons.

Despite an intense HIV/AIDS epidemic during which life expectancy dropped to less than 40 years by the early 2000s, the Botswana government’s investment in healthcare (and most notably HIV care) was able to reverse this decline with an increase in longevity to over 65 years currently (6,7). Botswana had one of the first public antiretroviral treatment programs in Africa and has achieved remarkable coverage with over 90% of citizens requiring treatment currently on therapy, according to government estimates (8). While HIV incidence may be declining in Botswana , the burden of chronic infection is immense with an estimated 25% of adults living with HIV(4).

As AIDS-related mortality has plummeted, the late sequelae of chronic HIV infection have risen and cancer in particular has emerged as a public health challenge in Botswana. At two referral hospitals, wards previously full with HIV-infected patients with tuberculosis and other opportunistic conditions have been repurposed as oncology wards. Antiretroviral therapy has been associated with decreased incidence of Kaposi’s sarcoma, but other AIDS-defining and non-AIDS-defining cancers have increased in incidence since treatment became available (9). Over 60% of patients with cancer are HIV-infected (10). Cancer prevention and early detection by screening, aside from a growing program in cervical cancer, are not routine leading to late diagnosis and presentation with advanced disease among both HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected patients (11). Leading malignancies in Botswana are Kaposi’s sarcoma; cervical, breast, head and neck, esophageal, and prostate cancer; and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (12).

One of the main challenges for cancer care in Botswana is the lack of human capital, i.e. trained specialists in many fields, including pathology, clinical oncology, radiology, surgical subspecialties, and medical physics and engineering. Botswana is hoping to address this issue through developing efforts in post-graduate training at the University of Botswana School of Medicine, but a well-established oncology training program does not yet exist, resulting in a significant shortage of care providers and expertise in the country to cope with the rapidly growing cancer burden.

As recently reviewed (13), core oncologic infrastructure does exist in Botswana. Limited specialized oncologic care is available in three government hospitals (Princess Marina Hospital (PMH) in Gaborone, Nyangabgwe Referral Hospital in Francistown, and Letsholathebe II Memorial Hospital in Maun) (see Figures 2,3) and two private facilities (Gaborone Private Hospital and Bokamoso Private Hospital in Gaborone) but this care is limited by human capital and unreliable access to medications and diagnostics. Expatriate oncologists, recruited to Botswana via a service program of the government of China or via a for-profit Indian medical staffing company, supervise care at the public oncology facilities along with generalists (medical house officers). Since 2007, medical oncologists from the Texas Children’s Hospital have provided specialized care for children with cancer. A small number of clinical oncologists (trained in both radiation and medical oncology at foreign institutions) practice in the private sector. At the government and sometimes even private facilities, there are shortages of chemotherapy and other antineoplastic drugs, leading to interruptions or missing components of multidrug regimens, as well as shortages of drugs to manage the complications of therapy, including antiemetics, antibiotics, narcotics, and growth factors. There are also challenges with regard to cancer diagnosis, as both the tools and personnel to perform biopsies are in short supply, often delaying the start of treatment.

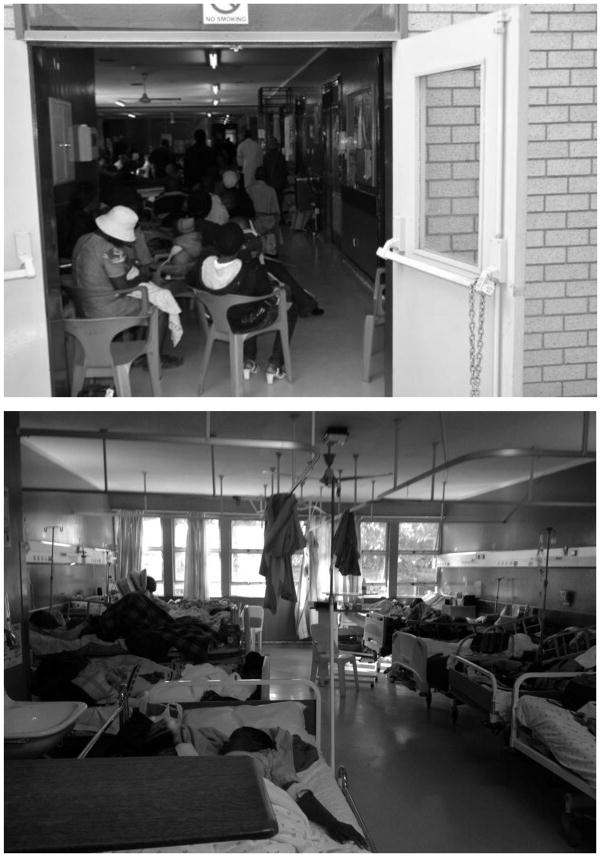

Figure 2. Princess Marina Hospital, Gaborone, and Nyangabgwe Referral Hospital, Francistown.

Long waits and crowded facilities are common in these referral hospitals.

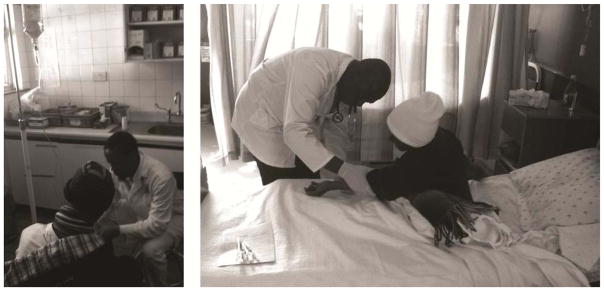

Figure 3.

Chemotherapy administration at Princess Marina Hospital.

The National Health Laboratory (NHL), a government institution in Gaborone, and Nyangabgwe Referral Hospital in Francistown provide the majority of pathology services in Botswana. The Ministry of Health employs four anatomic pathologists to interpret specimens from throughout the country. The NHL alone receives approximately 35,000 specimens, including over 24,000 Papanicolaou smears, each year. The typical time from receipt of a specimen to reporting generally exceeds one month. This prolonged turn-around time is not only due to a lack of human capital, but also a lack of the necessary equipment to care for a population this large.1 For the vast majority of specimens, histologic appearance alone is used for diagnosis and grading of malignancies.

Currently, radiation therapy is only available at Gaborone Private Hospital (GPH). While radiation is administered in the private sector, the Botswana government has made this available for all citizens by fully supporting the costs of treatment for the 90% of patients without sufficient private medical insurance. A single linear accelerator and a high dose rate (HDR) brachytherapy device are housed at GPH. With a population of 2 million, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) recommendations would indicate the need for four to eight linear accelerators in Botswana (14), far more resources than currently available. Notably, however, other sub-Saharan countries with significantly larger populations (e.g. Rwanda and Mozambique) have no such facility. A teaching hospital affiliated with the University of Botswana is under construction and plans to include radiotherapy services in the future.

The oncology department at GPH is staffed by two oncologists, a medical physicist, nurses, therapists, and a dosimetrist, and treats approximately 60 patients per day, the majority for curative intent (80% radical, 20% palliative). The linear accelerator (Elekta Precise, Stockholm, Sweden) has independent jaws but no multi-leaf collimator. Customized cerrobend blocking is utilized in up to 15% of cases. Verification imaging is performed using conventional radiographic films. A dedicated CT simulator (Philips AcQSim, Amsterdam, Netherlands), which also often serves as a source of diagnostic/staging imaging, is available and three-dimensional treatment planning is performed for both external beam and brachytherapy.

BOTSOGO Collaboration

Following a year long needs assessment in 2011 and in order to help improve cancer care in Botswana, the MGH/Harvard Medical School community has partnered with the oncology community and government of Botswana to form the BOTSOGO (BOTSwana Oncology Global Outreach) initiative (15). The name BOTSOGO, pronounced “bot-so-ho” is taken from the Setswana (primary language for most Batswana) word for “health.” This collaborative effort in oncology care was spurred by existing relationships in HIV/AIDS research and care delivery developed within the Botswana-Harvard AIDS Institute Partnership (BHP). BHP, founded in 1996, is an independent not for-profit research organization in Gaborone affiliated with the Harvard School of Public Health and the Botswana Ministry of Health.

The initial efforts of the BOTSOGO initiative have been organized around the following themes: 1) on-site visits to share expertise in clinical cancer care for capacity building purposes in identified areas of most need and/or impact, 2) developing a forum for multi-disciplinary case discussions and education, 3) identifying and conducting collaborative research initiatives, and 4) relationship building with local stakeholders for long-term sustainability and growth.

Clinical Care and Capacity Building

Likely driven by prevalent HIV infection, Botswana has one of the highest rates of cervical cancer in the world with an age-standardized incidence of 38 per 100,000 women (compared to less than 10/100,000 in developed countries) (9), and it is the leading cause of cancer-related mortality (16). The Botswana-University of Pennsylvania collaboration has pioneered capacity development in screening and early detection of cervical lesions (17). We sought to complement these activities by providing hands-on training and mentorship, with initial efforts focused on enhancing capacity for cervical cancer treatment.

Once diagnosed, cervical brachytherapy is a critical tool in disease management and along with external beam radiotherapy can be curative even for locally advanced disease (18). Prior to 2012, patients were sent to South Africa to receive brachytherapy. It was the consensus of local care providers and the government of Botswana that the development of local capacity for brachytherapy was a high priority. A modern HDR device (Nucletron/Elekta AB, Stockholm, Sweden) was purchased and installed at GPH in 2011 and insertions began in February 2012.

The first visit of the BOTSOGO team coincided with the initiation of cervical brachytherapy in Botswana. Hands-on, practice-changing guidance was provided for treatment planning, equipment selection, ultrasound image guidance, source insertion, and patient management. A follow-up visit occurred in September 2012, when approximately 25 cases were performed over a one-week period (Figure 4). This visit helped to alleviate a three-month brachytherapy backlog. Of note, insertions were challenging due to fibrosed cervices and delay-induced tumor recurrences. Titanium tandem and split ring (TSR) treatments were initiated with a donated applicator set (Mick Radio-Nuclear Instruments, Inc., Mount Vernon, NY). Titanium TSR applicators provide ideal geometry for the advanced disease typically seen in Botswana. Further visits by our team in May and September 2013 and additional support from the Botswana University of Pennsylvania collaboration have helped optimize the procedure. The oncologists at GPH have now developed significant expertise and treat 30–50 brachytherapy cases per month.

Figure 4.

Ultrasound-guided cervical brachytherapy insertion, Gaborone Private Hospital.

With successful development of capacity in brachytherapy administration, the focus of visits have expanded to include patient care and treatment planning case discussions for external beam radiation therapy, including disease management with a particular focus on pelvic and head & neck malignancies, as well as quality and safety. A distance–learning program for physicians, therapists, nursing and physics staff is under development.

The BOTSOGO initiative has since grown to include all cancer related disciplines. MGH medical and surgical oncologists visited Botswana in May 2013 focusing on lymphoma and breast cancer management, and providing patient care and didactic teaching at Princess Marina Hospital (PMH) in Gaborone and Nyangabgwe Referral Hospital in Francistown(15). In September 2013, a visit by a MGH pathologist looked to help address possible bottlenecks at NHL, including the donation of an additional microtome for processing of pathology slides. A full-time MGH faculty medical oncologist is now based in Botswana as of March 2014 to provide specialized clinical care, training of medical students and residents, assist with quality improvement measures, and conduct research initiatives.

Multi-disciplinary Tumor Board and Educational Initiatives

We have established the first sustainable multidisciplinary tumor board in Botswana, which connects the Botswana oncology community (including oncologists, surgeons, pathologists, infectious disease physicians, house officers, nurses, therapists, and students) with MGH/Harvard-based disease site experts (see Figure 5). Since its initiation during the first visit of the BOTSOGO team to Botswana in February 2012, the tumor board has met monthly to discuss specific patient management challenges. Attendees in Botswana and the US have been able to conduct these meetings via an internet-based platform (WebEx, Santa Clara, California). Thus, we have fostered relationships not only between care providers in Botswana and MGH/Harvard, but also among care providers from different disciplines and different institutions within Botswana. In addition to providing a venue for education and constructive peer review, the conference provides a regular forum to discuss relevant health systems issues.

Figure 5.

Botswana-Harvard Multidisciplinary Tumor Board. Top panel in Gaborone, and bottom panel in Boston.

The tumor board has covered a wide range of cases and topics selected by care providers of patients in Botswana, including common (e.g. cervical, breast, head and neck, Kaposi’s sarcoma, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma) and uncommon (e.g. leiomyosarcoma, vaginal carcinoma, penile, gastrointestinal stromal tumor, pediatric) cancers (see Table 1). Case presentations by the treating physicians in Botswana are followed by an open discussion of challenging diagnostic, treatment, or heath system issues that impact the care of the patient. The conference concludes with a focused review of best practice by disease site experts, and possible strategies for adapting these to clinical circumstances in Botswana and for HIV-infected patients (19).

Table 1.

BOTSOGO Multi-disciplinary Tumor Board Case Summaries

| Date | Title | Cancer Type | HIV status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feb-12 | A woman with cervical cancer | Cervix | + |

| Apr-12 | A 58 year-old male with lung mass | Lung | − |

| May-12 | A 35 year-old woman with leiomyosarcoma | Leiomyosarcoma | + |

| Jul-12 | A 20 year-old man with hepatocellular carcinoma | Hepatocellular carcinoma | − |

| Aug-12 | A 65 year-old woman with dark heel mass | Melanoma | Declined test |

| Sep-12 | A 39 year-old with Non-Hodgkins lymphoma | Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma | + |

| Nov-12 | A 36 year-old female with epigastric pain | GIST | − |

| Dec-12 | A 29 year-old woman with a breast mass | Breast | − |

| Jan-13 | A 39 year-old male with bilateral pleural effusion | Kaposi Sarcoma | + |

| Feb-13 | A 35 year-old woman with HIV and a tonsilar mass | Tonsilar SCC | + |

| Mar-13 | A 47 year-old female with post-coital bleeding | Vagina | + |

| Apr-13 | Two men with breast masses | Breast | − |

| May-13 | A 38 year-old woman and a 26 year-old man with neck and axillary masses | NHL | Pt 1: + Pt 2: − |

| Jun-13 | Oncologic management of a large neck mass | Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor | + |

| Jul-13 | Two women with rectal masses | Rectal adenocarcinoma | − |

| Sep-13 | A 29-year-old with vulvar cancer | Vulvar | + |

| Oct-13 | 5 children with lower extremity masses | Osteosarcoma | − |

| Nov-13 | Two men with penile lesions | Penile | + |

| Dec-13 | Two men with groin and neck swelling | Castleman’s disease | + |

| Feb-14 | A 52 year old woman with an enlarging perineal mass | Myoepithelioma | − |

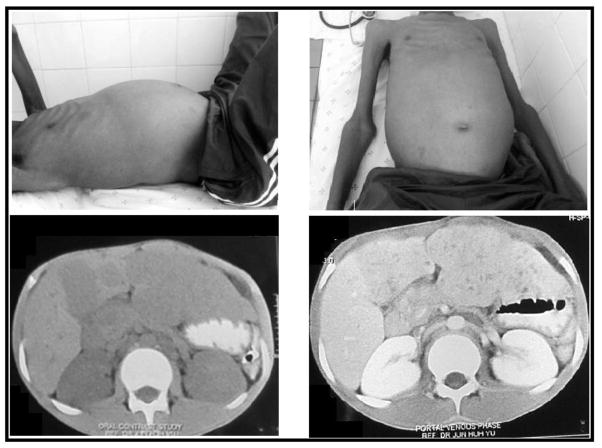

A recurrent theme throughout the conferences is that barriers to diagnosis and care often result in advanced disease (see Figure 6). These barriers include long-distance travel to referral hospitals for those living in less accessible areas, a decreased awareness of the signs and symptoms of cancer, a tendency to seek opinions from traditional healers, processing delays for pathology specimens, limited access to appropriate drugs and therapies, and wait times associated with large patient numbers in a resource-limited setting.

Figure 6. Subject of Multidisciplinary Tumor Board.

20-year old male presenting with weight loss, vomiting, abdominal pain and distension, diagnosed with hepatocellular carcinoma. CT shows multi-nodulated masses within the left lobe of the liver and hilum with dilated intrahepatic biliary ramifications in the region of the caudate and left lobes.

In addition to enhancing the core activities of the tumor board, the BOTSOGO collaboration is planning a 3-day oncology symposium (co-sponsored with Botswana Ministry of Health, University of Botswana, Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Hospital and University of Pennsylvania) in Gaborone to further catalyze the development of a Botswana comprehensive cancer control plan, standardized cancer treatment guidelines, local engagement in oncology research, and improved provision of cancer care.

Research Initiatives

Many facets of the cancer problem in sub-Saharan Africa remain poorly understood (20). The spectrum of disease, its relationship to viral pathogens (e.g. HIV, EBV, HPV) and other exposures, and successful approaches to treatment with limited resources require further definition. Addressing these knowledge gaps to enable quality care and prevention has emerged as a priority of the BOTSOGO collaboration. Again leveraging the resources of the Botswana Harvard AIDS Institute, the collaboration has supported the development of research infrastructure including support to the Botswana National Cancer Registry, sustained the Botswana Prospective Cancer Cohort, and promoted a number of collaborative research projects that build on these shared resources.

Stakeholder Collaboration

Integrated oncologic care is complicated and demands a multi- and inter-disciplinary process with many invested partners. In addition to building strong relationships with the oncology teams at GPH and on the wards of the two main referral hospitals, PMH and Nyangabgwe Referral Hospital, we have also actively collaborated with representatives from the Botswana Ministry of Health, Botswana-Harvard AIDS Institute Partnership, NHL, University of Botswana, the Cancer Association of Botswana, Botswana-University of Pennsylvania collaboration, Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Hospital and the US Embassy in Botswana. Through these robust partnerships and a shared common goal of improving the care of cancer patients, Botswana is poised to build itself a center of excellence in oncology for sub-Saharan Africa. Given the country’s success in addressing the HIV/AIDS crisis, this goal seems achievable.

Future Goals and Conclusions

In conclusion, a collaborative and sustainable relationship in oncology care has been established between MGH/Harvard and Botswana, anchored by regular tumor boards and on-site visits and exchanges that have resulted in the introduction of new approaches to treatment and perceived improvements in patient care. In the future, we aim to expand our teaching and training efforts in the multiple oncological specialties, further address issues of drug and equipment access, continue to promote public education about cancer, provide bidirectional exchange opportunities for faculty and trainees, and foster ongoing research links to study cancer in the setting of HIV. The BOTSOGO collaboration provides one model for partnership between academic oncology centers and high burden countries with limited resources.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Botswana Harvard AIDS Institute— especially Joseph Makhema, Max Essex, Shahin Lockman, Matthew Boyer, Hermann Bussman, Aida Asmelash, and Kathleen Powis—for welcoming oncology as part of their mission and supporting the growth of the collaboration. Similarly, the collaboration could not have been sustained without the dedication of key clinical staff of Princess Marina Hospital and Gaborone Private Hospital, including Kamal Verma, Babe Gaolebale, Tlotlo Bathethi Ralefala, Jane Gillead Tieng’o, Saleh Mudjana, Lin Ragbo, Michael Walsh, and Dawn Balang. We appreciate the partnership and guidance from Shenaz El-Halabi, Malebogo Pusoentsi, Heluf Medhin, Ndwape Ndwape, Haruna Jibril, Vincent Molelekwa and others at the Botswana Ministry of Health. Involvement of faculty volunteers, much of it in person in Botswana, has been crucial for the educational mission and acknowledge the contributions of Jay Loeffler, David Bangsberg, David Ryan, Lidia Schapira, Michele Gadd, Edwin Choy, James Cusack, Aliyah Sohani, Drucilla Roberts, Franklin Huang, Ami Bhatt, Phillip Gray, and Kimberley Mak of Massachusetts General Hospital; Doreen Ramogola-Masire, Lillie Lin, Timothy Rebbeck, Surbhi Grover, Carrie Kovarik, and Stephen Hahn of the University of Pennsylvania; Jeremy Slone and David Poplack of the Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Hospital; and Sandro Vento of University of Botswana School of Medicine. Finally, we appreciate the assistance of Alec Eidelman, Justin Eusebio, Katherine Dueholm and the US Embassy in Gaborone, Davi Chabner, and Michelle Adelman.

Supported by MGH Center for Global Health, Ira J. Spiro Award, Paul G. Allen Family Foundation, American Society of Clinical Oncology, in kind donations from Mick Radio-Nuclear Instruments, Inc., and by the NCI Federal Share of program income earned by Massachusetts General Hospital on C06 CA059267.

Footnotes

While capacity is being expanded, the NHL currently has one embedding station, one automated processor, and one microtome. They do not offer frozen sections, intraoperative cytology, electron microscopy, immunofluorescence, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or fluorescence in-situ hybridization (FISH) on tissue blocks. A limited array of immunohistochemistry (IHC) testing became available in early 2013; previously a small subset had been outsourced to South Africa for IHC.

Conflict of interest: none

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Brawley OW. Avoidable cancer deaths globally. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:67–8. doi: 10.3322/caac.20108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, et al. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–70. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farmer P, Frenk J, Knaul FM, et al. Expansion of cancer care and control in countries of low and middle income: a call to action. Lancet. 2010 Oct 2;376(9747):1186–1193. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61152-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.UNAIDS. Global Report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic 2013. Geneva: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leith JC. Why Botswana Prospered. Quebec City, Canada: McGill-Queen’s University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jamison DT. Disease and mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa. 2. Washington, D.C: World Bank; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. [Accessed August 22 2013];Global Health Observatory Data Repository. 2013 at http://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main.3?lang=en.

- 8.National AIDS Coordinating Agency. Progress Report of the National Response to the 2011 Declaration of Commitments on HIV and AIDS. Gaborone, Botswana: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dryden-Peterson S, Medhin H, Seage G, et al. Incidence of AIDS-defining and non-AIDS-defining cancers following expansion of ART, Botswana 2003–2008. 20th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infection; Atlanta, GA. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dryden-Peterson S, Medhin H, Iwe N, et al. Malignancies among HIV-Infected and HIV-Uninfected Patients in a Botswana Prospective Cohort. 19th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infection; 2012; Seattle, WA. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown CA, Dryden-Peterson S, Suneja G, et al. Effect of HIV on enrollment in oncology care in Botswana. Paper presented at: International Conference on Malignancies in AIDS and other Opportunistic Infections; 2013; Bethesda, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Botswana National Cancer Registry. Analysis of registered cancer patients, 1998–2008. Gaborone: Botswana Ministry of Health, Department of Public Health; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suneja G, Ramogola-Masire D, Medhin HG, Dryden-Peterson S, Bekelman JE. Cancer in Botswana: resources and opportunities. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:e290–1. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70283-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abdel-Wahab M, Bourque J, Pynda Y, et al. Status of radiotherapy resources in Africa: An international atomic energy agency analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:168–75. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70532-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chabner BA, Efstathiou JA, Dryden-Peterson S. Cancer in Botswana: The second wave of AIDS in sub-saharan africa. Oncologist. 2013;18:640–3. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferlay J, Shin H-R, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2893–2917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramogola-Masire D, de Klerk R, Monare B, et al. Cervical cancer prevention in HIV-infected women using the “see and treat” approach in Botswana. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999) 2012;59(3):308–13. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182426227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Viswanathan AN, Thomadsen B American Brachytherapy Society Cervical Cancer Recommendations C. American Brachytherapy Society consensus guidelines for locally advanced carcinoma of the cervix. Part I: general principles. Brachytherapy. 2012 Jan-Feb;11(1):33–46. doi: 10.1016/j.brachy.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramogola-Masire D, Russell AH, Dryden-Peterson SL, Efstathiou JA, Kayembe MKA, Wilbur DC. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case A 47-Year-Old Woman in Botswana with Post-Coital Bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2014 doi: 10.1056/NEJMcpc1400839. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parkin DM, Sitas F, Chirenje M, Stein L, Abratt R, Wabinga H. Part I: Cancer in Indigenous Africans--burden, distribution, and trends. Lancet Oncol. 2008 Jul;9(7):683–692. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70175-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]