Abstract

Background

African Americans (AAs) have been shown to exhibit a higher incidence of colorectal cancer and experience lower survival compared with whites. There is disagreement regarding the age at which to initiate screening in AAs.

Objectives

To calculate the age-specific incidence in AAs compared with whites while controlling for differences in socioeconomic status (SES) and to calculate the joinpoint at which the incidence begins to increase in each race.

Design

Retrospective database review.

Setting

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database.

Patients

All patients with adenocarcinoma of the colon or rectum from 2000 through 2011 in the SEER 18 database.

Interventions

We calculated the joinpoint of the upward trend of the age-adjusted incidence rate to determine the age at which the slope of the incidence curve began to increase in each race, while controlling for differences in SES by using a composite socioeconomic index.

Main Outcome Measurements

Age-adjusted incidence of colon and rectal cancer.

Results

The age-specific incidence of colorectal cancer (cases per 100,000 population) was 0.3 versus 0.4 in whites compared with AAs at 20 years of age. At 50 years of age, the incidence was 44.2 compared with 62.6 in whites compared with AAs. The model indicated a joinpoint at 47 years of age for whites (95% confidence interval, 45–49) and 43 for AAs (95% confidence interval, 42–45) (P < .001.) When SES was considered in stratification, joinpoints for whites were 48, 47, and 46 at high, middle, and low SES, respectively. Conversely, joinpoints of 43, 44, and 42 in the corresponding SES for AAs were noted (P ≤ .001).

Limitations

There was no intervention, and we cannot conclude that changing screening policy would affect this disparity.

Conclusion

There is a disparity in the age-specific incidence of colorectal cancer in AAs compared with whites beginning at 45 years of age. These differences persist across socioeconomic strata.

Over the past 5 years, an average of 145,000 new cases of colorectal cancer (CRC) were diagnosed per year in the United States, whereas 49,000 people per year died of this disease.1 The American Cancer Society estimates that 50% to 60% of these deaths may have been prevented if all men and women older than 50 years of age were routinely screened.2 Screening for CRC has been widely advocated by multiple professional organizations since it was first proposed in 1996.3 Colonoscopy has been shown to reduce the incidence of,4 as well as reduce the risk of death from,5 CRC. Multiple agencies have proposed screening guidelines for the early detection and prevention of CRC.6–9 Recent data indicate that the incidence of CRC in the United States has been decreasing,10 whereas other countries without aggressive screening and education have not seen the same decreases.11

There is additional interest in identifying vulnerable populations who may benefit from more intense screening. Patients with a family history of CRC, ulcerative colitis, hereditary nonpolyposis CRC, or familial adenomatous polyposis have been selected for more intense screening regimens compared with the general public.6–9 The American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) recently added the African American (AA) race as another high-risk patient group, proposing screening average-risk AA patients with colonoscopy starting at 45 years of age instead of 50 years of age.9 This recommendation was based on a special report from the ACG Committee on Minority Affairs and Cultural Diversity from 2005,12 which found a higher incidence of CRC in AAs,10,13–16 a lower survival rate in AAs with CRC,17–21 and a more proximal distribution of cancers in AAs.22–24 Despite these findings suggesting a higher overall incidence of CRC in AAs, the recommendation was made without citing any literature to suggest an earlier incidence of CRC in AAs. In 2010, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) also recommended screening AAs at 45 years of age, citing the ACG recommendation as the basis for this recommendation.25 The joint American Cancer Society, U.S. Multi-Society Task Force, and American College of Radiology consensus agreed to postpone further recommendations on the age at which to initiate screening in AAs until a later date, citing a lack of evidence that early screening in AA patients would positively affect screening or survival rates.8

To make informed recommendations about the age of screening initiation, we must understand the epidemiology of CRC among different populations. The purpose of this study was to clarify the age-specific incidence of CRC in AAs compared with whites, while accounting for socioeconomic factors, because lower socioeconomic status (SES) was previously correlated with lower use of screening modalities.

METHODS

The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database from the National Cancer Institute from 2000 through 2011 was used to determine the epidemiology of CRC by calculating the age-specific incidence in AAs compared with whites.

SEER database

Description taken from the SEER Web site26: “The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program of the National Cancer Institute currently collects and publishes cancer incidence and survival data from population-based cancer registries covering approximately 28% of the U.S. population. For more information on this, please view the SEER Research Data. SEER coverage includes 26 percent of African Americans, 38 percent of Hispanics, 44 percent of American Indians and Alaska Natives, 50 percent of Asians, and 67 percent of Hawaiian/Pacific Islanders. The SEER Program registries routinely collect data on patient demographics, primary tumor site, tumor morphology and stage at diagnosis, first course of treatment, and follow-up for vital status. Geographic areas were selected for inclusion in the SEER program based on their ability to operate and maintain a high quality population-based cancer reporting system and for their epidemiologically significant population groups.” Registries represent the Northeast (Connecticut and New Jersey), South (Kentucky, Louisiana, Atlanta, Rural Georgia, and Greater Georgia), North-Central (Detroit and Iowa), and West (Hawaii, New Mexico, Seattle-Puget Sound, Utah, San Francisco-Oakland, San Jose-Monterey, Los Angeles, Greater California, Arizona, and Alaska).

We used SEER Stat version 8.02 software (National Cancer Institute, Silver Spring Md). The SEER database for the period from 2000 to 2011 was used to calculate the age-specific incidence of colon and rectal adenocarcinoma based on race and socioeconomic factors. Incidence rates were age-adjusted to the age of the U.S. census population from 2000 and reported as the number of cases per 100,000. We selected patients from the SEER 18 registry with a confirmed cancer diagnosis and older than 20 years of age. The populations in the dataset were adjusted by SEER for population shifts that occurred as a result of Hurricane Katrina. Cases were selected by site (colon excluding appendix and rectum) and histology codes (adenocarcinoma).

To account for socioeconomic factors, we stratified our incidence calculations by county-level SES by using the poverty rate, described as the percentage of families below the poverty level, as previously detailed by Singh et al.27 The poverty rate has been shown to be a measure of economic deprivation and an uneven distribution of economic resources in a given population. It has also been shown to correlate highly with other methods of economic deprivation such as educational attainment, unemployment rate, and occupational composition.27 Patients were stratified by quartiles according to county-level poverty rate.

Joinpoint regression (JR) models were used to fit the upward trend of the age-adjusted incidence rate and determine the age at which the slope of the incidence curve began to increase in each race. Standard errors of age-adjusted incidence rates were used as weights to account for heteroscedasticity in the weighted least-squares estimates of the JR models. Initial results from single and multiple joinpoint models indicated that a joinpoint existed in the age range of 40 to 55 years; we therefore decided to use a 1-joinpoint model for parsimony and focus on assessing this joinpoint and comparing it between race groups in a formal analysis. Joinpoints, slopes, and intercepts were determined for both white and AA groups by using the JR models and compared by using z tests. The same analyses were repeated in subsets when individuals were stratified by their SES and geographic locations of residence.

For the purpose of validation, we categorized individuals into multiple age groups (by using every 5 years as a group) and performed a fixed-effects model to assess the association between the age-adjusted incidence with the fixed effects of race and age groups. Age-adjusted rates were computed by using SEER Stat 8.2 or STATA version 13.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Tex); JR models were computed by using the Joinpoint Regression Program 4.0.4 (downloaded free from http://surveillance.cancer.gov/joinpoint/). Other statistical analyses were performed by using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute). P values <.05 were considered statistically significant. This study was approved by the institutional review board of our institution.

RESULTS

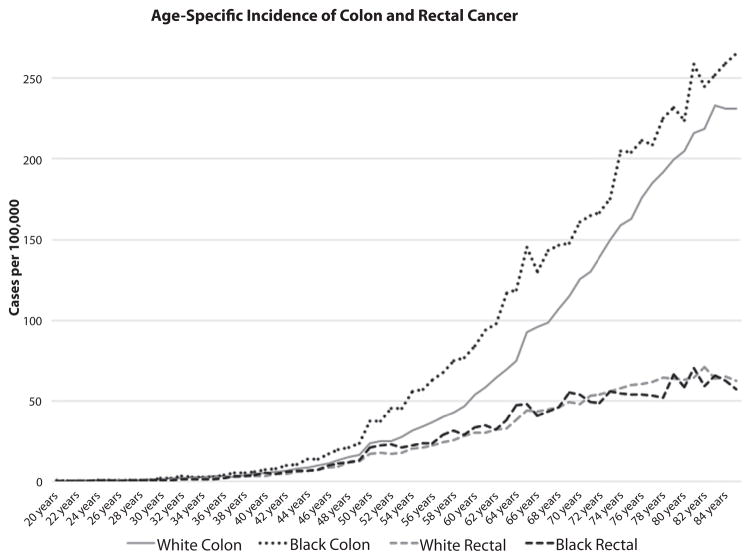

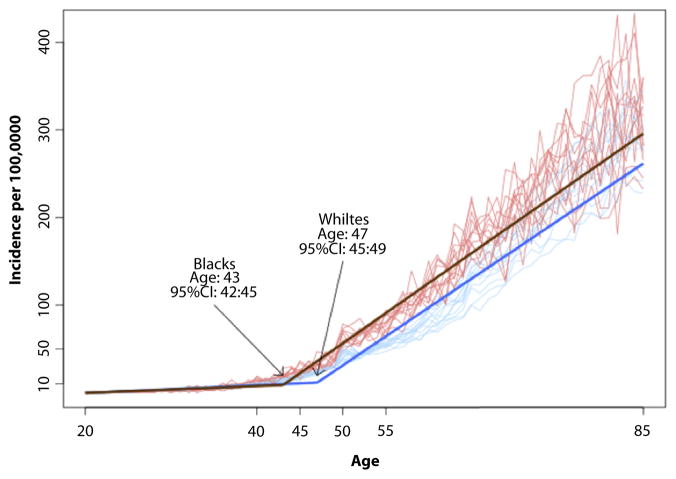

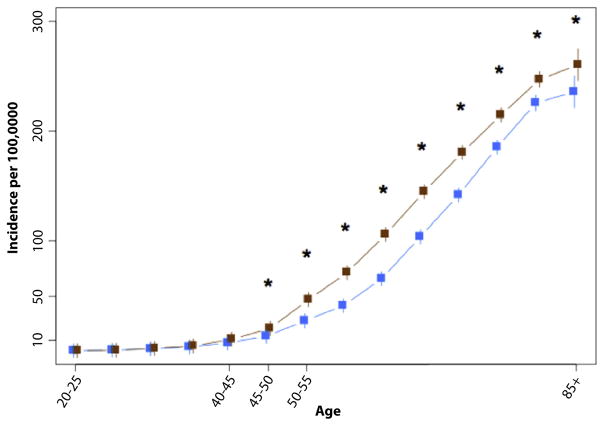

From 2000 to 2011, 395,713 cases of CRC were identified in the SEER database, yielding an annual incidence of 40.6 per 100,000 (whites, 40.6 per 100,000; AAs, 40.7 per 100,000). Figure 1 demonstrates no difference in the age-specific incidence of rectal cancer between whites and AAs, but demonstrated a large difference in the incidence of CRC. The JR model indicated a joinpoint for CRC as a whole at 47 years of age for whites (95% confidence interval, 45–49), and 43 for AAs (95% confidence interval, 42–45) (P< .001) (Fig. 2). The mean incidence rates were compared between race groups in each age category in a validation model (Fig. 3). Differences in incidence were significant, starting with the age category of 45 to 50 years, and AAs had a higher incidence of CRC after 45 years of age.

Figure 1.

Age-specific incidence of colon and rectal cancer, by race.

Figure 2.

Joinpoint regression analysis of the age at which colorectal cancer begins to increase, by race.

Figure 3.

Validation joinpoint model of age-specific incidence of colorectal cancer, by race. *P < .05.

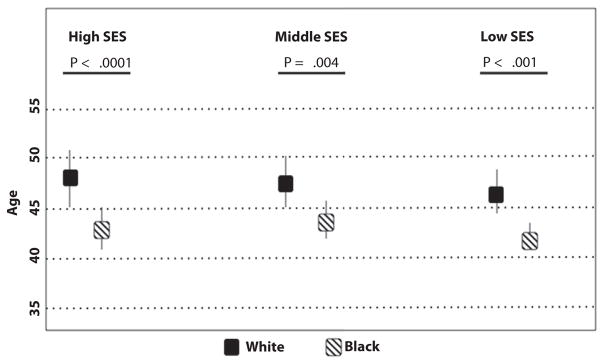

The joinpoints were compared between race groups in subpopulations stratified by SES (Fig. 4). Joinpoints for whites were 48, 47, and 46 of high, middle, and low SES, respectively. Conversely, joinpoints of 43, 44, and 42 in the corresponding SES for AAs were noted (P < .001).

Figure 4.

Joinpoint indicating the age at which colorectal cancer incidence begins to increase, by race (95% confidence interval represented by bars). SES, socioeconomic status.

DISCUSSION

To make informed decisions regarding cancer screening for a population, the epidemiology, particularly the age distribution of the malignancy, must be well known. This study has several important findings that detail these critical epidemiologic factors in CRC. First, there is a discrepancy in the incidence of colon cancer, but not rectal cancer, in AAs compared with whites. The incidence of CRC in whites begins to increase at 47 years of age, whereas the incidence in AAs begins to increase at 43 years of age, a difference that persists when county-level socioeconomic factors are accounted for. Although the SEER database accounts for 26% of the U.S. population, the incidence figures among both races have been shown to correlate between SEER data28 and data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,29 which uses data from the National Program of Cancer Registries, suggesting that the incidence figures provided by SEER are applicable to the general population.

Socioeconomic barriers in CRC between AA and white patients on a societal level have clearly been described,12,30 and AAs have a higher incidence of CRC and poorer survival rates than whites.31 However, in the U.S. Veterans Affairs Health Care System, which is an equal-access system, there is either no or minimal survival differences between AA and white patients with CRC.32,33 Brounts et al2 also described equal use of screening for CRC in AA and white patients in an equal-access system of the Department of Defense beneficiaries. Similarly, AA patients participating in adjuvant chemotherapy trials have survival rates similar to those of white patients.34 These factors were detailed in a special report from the ACG Committee on Minority Affairs and Cultural Diversity from 2005,12 leading the ACG to recommend screening average-risk AAs with colonoscopy starting at 45 years of age.9 A critical review of all references cited by the ACG does not reveal any evidence of an earlier onset of cancer in AAs compared with whites. Additionally, in 2010, the ASGE also recommended screening at 45 years of age.25 The ASGE made this recommendation in light of the 20% higher stage-adjusted mortality experienced by AAs and younger age at presentation in this ethnic group. Specific references cited a lower median age (67 vs 73 years) in AAs compared with whites by using SEER data from 1996 to 200235 and a higher proportion of cases diagnosed in AA patients younger than 50 years of age in the state of California from 1988 to 1995.15 Other agencies, including the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force,7 and the American Cancer Society8 continue to recommend the initiation of screening at 50 years of age in both races. Our study expands on these findings by introducing current national age-specific incidence figures while controlling for differences in SES.

Our study is the first study to use national data and robust statistical analysis to control for differences in SES in understanding the epidemiology of CRC. However, eliminating this disparity in incidence is a much more complex than simply decreasing the age of screening in AA patients because screening recommendations must be adhered to if they are to be effective. Current literature suggests some important differences in CRC screening rates between AA and whites. The American Cancer Society indicates that 61.5% of whites older than 50 years of age and 55.5% of AAs older than 50 years of age were in compliance with current screening guidelines defined as fecal occult blood test within 1 year or lower endoscopy defined as flexible sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy within 10 years.36 Importantly, approximately 60% of both whites and AAs 50 years of age and older received appropriate screening if they had health insurance. The same study indicated that only 19.4% of uninsured AAs and 24.2% of uninsured whites received appropriate screening.36 This report cited that the lack of education and health insurance coverage was associated with poorer compliance with screening recommendations.

Although the incidence curves of CRC were demonstrated to separate beginning at 45 years of age, the majority of the discrepancy in incidence occurs after 50 years of age. It is unclear whether the best strategy to mitigate this disparity would be to initiate earlier screening, as proposed by the ACG and ASGE, or to improve overall rates of screening in the AA population older than 50 years of age. Gupta et al37 estimated that screening the AA population at 45 years of age (assuming current screening rates) would detect the same number of cases of CRC in AAs as the strategy of continuing to initiate screening at 50 years of age and increasing current screening rates by 5%. The authors also estimated that increasing screening participation in AAs by 10% over current rates would be more effective because 67% of the AA patients with CRC were 60 years of age and older, whereas 5% were 45 to 49 years of age. A detailed analysis of the cost-effectiveness of alternative strategies is beyond the scope of this article.

This study has methodological limitations as well. Although the SEER database has been designed to be a representative sample of the U.S. population and the SEER incidence figures correlate with those from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, we cannot be sure that a different trend would not be observed in the population not included in the SEER database. We have no information about each patient’s personal or family history of polyps or cancer. We also do not know how many of these patients had a higher risk of cancer such as familial adenomatous polyposis, Lynch syndrome, and chronic ulcerative colitis. Additionally, these conditions account for a small minority of cases of CRC in a population (familial adenomatous polyposis, <1%; Lynch syndrome, 2%–3%; ulcerative colitis, <1%). Patient characteristics such as smoking, obesity, and alcohol use are not available at the population level, and we cannot be sure that the distribution of these conditions was equal in both races. Additionally, robust discrimination between African ancestries was not available, so we cannot determine whether incidence figures would differ among different ancestries. There was also no intervention in this study. The joinpoint analysis does not give us the ability to determine whether changing screening in a specific population would affect the incidence of CRC; it only is able to highlight the age at which this disparity begins. However, we believe that the data from this study, combined with the known rates of screening colonoscopy, will help policymakers to decide how to focus their efforts on improving screening rates and which populations to target.

There is a disparity in the age-specific incidence of CRC in AAs compared with whites beginning at 45 years of age. These differences persist across socioeconomic strata. These epidemiologic data should be used as the basis for further evaluating strategies to mitigate this disparity.

Abbreviations

- AA

African American

- ACG

American College of Gastro-enterology

- ASGE

American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

- CRC

colorectal cancer

- JR

joint regression

- SEER

Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results Database

- SES

socioeconomic status

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE: All authors disclosed no financial relationships relevant to this article.

References

- 1.National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health. [Accessed May 7, 2013]; http://www.cancer.gov.

- 2.Brounts LR, Lehmann RK, Lesperance KE, et al. Improved rates of colorectal cancer screening in an equal access population. Am J Surg. 2009;197:609–12. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.12.006. discussion 612–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Markowitz AJ, Winawer SJ. Screening and surveillance for colorectal carcinoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1997;11:579–608. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8588(05)70452-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, Ho MN, et al. Prevention of colorectal cancer by colonoscopic polypectomy. The National Polyp Study Workgroup. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1977–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312303292701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zauber AG, Winawer SJ, O’Brien MJ, et al. Colonoscopic polypectomy and long-term prevention of colorectal-cancer deaths. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:687–96. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1100370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davila RE, Rajan E, Baron TH, et al. ASGE guideline: colorectal cancer screening and surveillance. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:546–57. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Screening for colorectal cancer. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:627–37. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-9-200811040-00243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, et al. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:130–60. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rex DK, Johnson DA, Anderson JC, et al. American College of Gastro-enterology guidelines for colorectal cancer screening 2009 [corrected] Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:739–50. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al., editors. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2011. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: [Accessed April 3, 2015]. Available at http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2011/ [Google Scholar]

- 11.Center MM, Jemal A, Ward E. International trends in colorectal cancer incidence rates. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:1688–94. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agrawal S, Bhupinderjit A, Bhutani MS, et al. Colorectal cancer in African Americans. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:515–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41829.x. discussion 514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghafoor A, Jemal A, Cokkinides V, et al. Cancer statistics for African Americans. CA Cancer J Clin. 2002;52:326–41. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.52.6.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Troisi RJ, Freedman AN, Devesa SS. Incidence of colorectal carcinoma in the U.S: an update of trends by gender, race, age, subsite, and stage, 1975–1994. Cancer. 1999;85:1670–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Theuer CP, Wagner JL, Taylor TH, et al. Racial and ethnic colorectal cancer patterns affect the cost-effectiveness of colorectal cancer screening in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:848–56. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.22535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parker SL, Davis KJ, Wingo PA, et al. Cancer statistics by race and ethnicity. CA Cancer J Clin. 1998;48:31–48. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.48.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clegg LX, Li FP, Hankey BF, et al. Cancer survival among US whites and minorities: a SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results) Program population-based study. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1985–93. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.17.1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merrill RM, Henson DE, Ries LA. Conditional survival estimates in 34,963 patients with invasive carcinoma of the colon. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:1097–106. doi: 10.1007/BF02239430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mandelblatt J, Andrews H, Kao R, et al. The late-stage diagnosis of colorectal cancer: demographic and socioeconomic factors. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:1794–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.12.1794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wudel LJ, Jr, Chapman WC, Shyr Y, et al. Disparate outcomes in patients with colorectal cancer: effect of race on long-term survival. Arch Surg. 2002;137:550–4. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.137.5.550. discussion 554–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freeman HP, Alshafie TA. Colorectal carcinoma in poor blacks. Cancer. 2002;94:2327–32. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Theuer CP, Taylor TH, Brewster WR, et al. The topography of colorectal cancer varies by race/ethnicity and affects the utility of flexible sigmoidoscopy. Am Surg. 2001;67:1157–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cress RD, Morris CR, Wolfe BM. Cancer of the colon and rectum in California: trends in incidence by race/ethnicity, stage, and subsite. Prev Med. 2000;31:447–53. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharma VK, Vasudeva R, Howden CW. Changes in colorectal cancer over a 15-year period in a single United States city. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3615–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cash BD, Banerjee S, Anderson MA, et al. Ethnic issues in endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:1108–12. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) [Accessed May 14, 2013]; Available at: http://www.seer.cancer.gov.

- 27.Singh GK, Miller BA, Hankey BF. Changing area socioeconomic patterns in U.S. cancer mortality, 1950–1998: part II–lung and colorectal cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:916–25. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.12.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Cancer Institute. Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) [Accessed July 22, 2014];Colorectal Cancer Statistics. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/colorect.html.

- 29.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed July 22, 2014];Colorectal Cancer Rates by Race and Ethnicity. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/colorectal/statistics/race.htm.

- 30.Dimou A, Syrigos KN, Saif MW. Disparities in colorectal cancer in African-Americans vs whites: before and after diagnosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:3734–43. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.3734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Desantis C, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:151–66. doi: 10.3322/caac.21173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dominitz JA, Samsa GP, Landsman P, et al. Race, treatment, and survival among colorectal carcinoma patients in an equal-access medical system. Cancer. 1998;82:2312–220. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19980615)82:12<2312::aid-cncr3>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rabeneck L, Souchek J, El-Serag HB. Survival of colorectal cancer patients hospitalized in the Veterans Affairs Health Care System. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1186–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCollum AD, Catalano PJ, Haller DG, et al. Outcomes and toxicity in African-American and Caucasian patients in a randomized adjuvant chemotherapy trial for colon cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1160–7. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.15.1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karami S, Young HA, Henson DE. Earlier age at diagnosis: another dimension in cancer disparity? Cancer Detect Prev. 2007;31:29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.American Cancer Society. Cancer prevention & early detection facts & figures 2013. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2013. [Accessed July 22, 2014]. Available at: http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@epidemiologysurveilance/documents/document/acspc-037535.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gupta S, Shah J, Balasubramanian BA. Strategies for reducing colorectal cancer among blacks. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:182–4. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]