Abstract

Once sought nearly exclusively by women, nonsurgical cosmetic procedures are increasingly being sought after by men. Reviewed here are survey data that characterize the spectrum of nonsurgical cosmetic procedures men are preferentially utilizing, the percentage of nonsurgical cosmetic procedures consumers who are men, and how some of these figures are changing with time. while men still comprise a small minority (approximately 10–20%) of those pursuing nonsurgical cosmetic procedures, this sector is growing, in particular for injection of neurotoxins. Practitioners performing nonsurgical cosmetic procedures on male patients need to be aware of anatomical, physiological, behavioral, and psychological factors unique to this demographic.

NONSURGICAL COSMETIC procedures (NSCPs), such as injection of neuromodulators and dermal fillers, laser treatments, and sclerotherapy, are becoming increasingly accepted and sought by mainstream society. For example, a recent survey from the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery (ASDS) indicated that dermatologists alone performed nearly three million neuromodulators and soft tissue filler procedures in 2013.1 Men are becoming increasingly concerned about their appearance. This is reflected not only by their increasing use of NSCPs, but also by their behaviors to maintain physique through use of anabolic steroids.2 While the NSCP market has historically been overwhelmingly dominated by female consumers, numerous studies and anecdotal experience suggest that there is increasing interest in these procedures among male patients. Further, physician attitudes toward these patients are changing as well.

While it had previously been posited that the prevalence of psychiatric disease among male cosmetic patients is higher than that among the general population, more recent studies suggest that this is not the case.3 In recognition of these trends, there are now specific centers dedicated to cater to the male cosmetic patient. The present review aims to compare available survey data across specialties and nations to qualitatively assess trends in utilization of NSCPs by men. Further, gender-specific differences in anatomy, physiology, and accordingly in technique are briefly reviewed for injectables (i.e., neurotoxins and soft tissue fillers) as well as sought-after laser treatments.

SURVEY DATA CHARACTERIZING TRENDS IN UTILIZATION OF NONSURGICAL COSMETIC PROCEDURES BY MEN

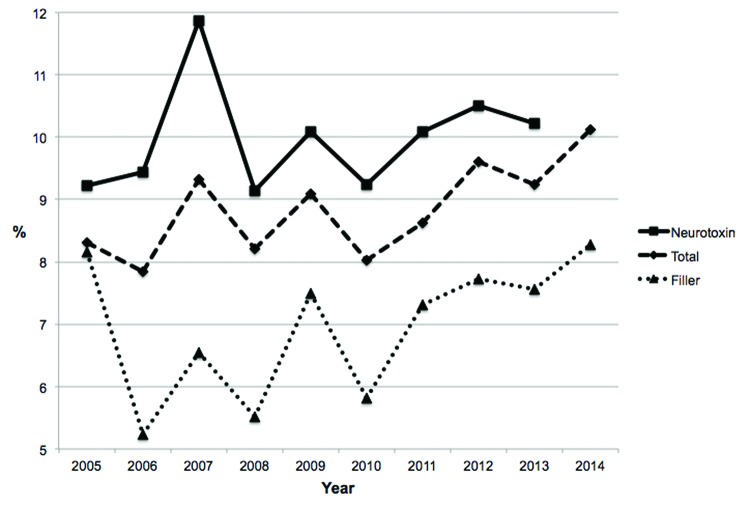

Since 2005, The American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (ASAPS) has been issuing an annual survey on cosmetic procedure utilization to more than 21,000 practicing dermatologists, plastic surgeons, and otolaryngologists.4–13 According to the 2014 ASAPS survey, the NSCPs with the highest percentage of male patients was intense pulsed light (13.9% males), laser hair removal (12.9% males), and neurotoxin injection (11.5% males) (Table 1). In each year the survey was administered, neurotoxin injections were by far the most popular NSCP for men. The ASAPS surveys suggest that the percentage of all NSCPs being performed in men is on the rise (Figure 1). In 2005, only 8.3 percent of NSCPs were performed on men, whereas this number increased to 10.1 percent in 2014 (Table 1). While the number of neurotoxin injections performed on men has increased from 9.2 to 11.5 percent from 2005 to 2014,the change in the percentage of soft tissue filler procedures being performed on men has been insignificant, from 8.2 to 8.3 percent, respectively. These results further suggest the overall number of NSCPs performed regardless of gender appears to be remaining relatively stagnant (Table 1). These data suggest that the rate at which males are seeking neurotoxin injections is growing more rapidly than that for females. The rate of growth for filler injections, however, is about the same for patients regardless of gender.

Table 1.

Gender-specific demographic data for nonsurgical cosmetic procedures from The American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery procedure surveys from 2005 to 20144–13

| YEAR | TOTAL | FEMALE TOTAL | FEMALE % | MALE TOTAL | MALE % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TOTAL PROCEDURES | 2005 | 9,297,730 | 8,525,713 | 91.7 | 772,017 | 8.3 |

| 2006 | 9,533,982 | 8,786,240 | 92.2 | 747,742 | 7.8 | |

| 2007 | 9,621,999 | 8,725,422 | 90.7 | 896,577 | 9.3 | |

| 2008 | 8,491,862 | 7,794,073 | 91.8 | 697,789 | 8.2 | |

| 2009 | 8,522,139 | 7,747,782 | 90.9 | 774,357 | 9.1 | |

| 2010 | 9,336,814 | 8,586,740 | 92.0 | 750,074 | 8.0 | |

| 2011 | 7,555,986 | 6,904,810 | 91.4 | 651,176 | 8.6 | |

| 2012 | 8,416,470 | 7,608,459 | 90.4 | 808,011 | 9.6 | |

| 2013 | 9,536,562 | 8,654,899 | 90.8 | 881,663 | 9.2 | |

| 2014 | 8,898,652 | 7,998,136 | 89.9 | 900,516 | 10.1 | |

| NEUROTOXIN | 2005 | 3,294,782 | 2,990,658 | 90.8 | 304,124 | 9.2 |

| 2006 | 3,181,591 | 2,881,119 | 90.6 | 300,472 | 9.4 | |

| 2007 | 2,775,175 | 2,445,656 | 88.1 | 329,519 | 11.9 | |

| 2008 | 2,464,123 | 2,239,024 | 90.9 | 225,099 | 9.1 | |

| 2009 | 2,557,068 | 2,299,282 | 89.9 | 257,786 | 10.1 | |

| 2010 | 2,437,165 | 2,211,930 | 90.8 | 225,235 | 9.2 | |

| 2011 | 2,619,739 | 2,355,455 | 89.9 | 264,284 | 10.1 | |

| 2012 | 3,257,913 | 2,915,865 | 89.5 | 342,048 | 10.5 | |

| 2013 | 3,766,148 | 3,381,476 | 89.8 | 384,672 | 10.2 | |

| 2014 | 3,588,219 | 3,174,856 | 88.5 | 413,363 | 11.5 | |

| FILLER | 2005 | 1,645,441 | 1,511,305 | 91.8 | 134,136 | 8.2 |

| 2006 | 1,972,131 | 1,868,934 | 94.8 | 103,197 | 5.2 | |

| 2007 | 1,723,478 | 1,610,616 | 93.5 | 112,862 | 6.5 | |

| 2008 | 1,528,829 | 1,444,505 | 94.5 | 84,324 | 5.5 | |

| 2009 | 1,579,897 | 1,461,550 | 92.5 | 118,347 | 7.5 | |

| 2010 | 1,547,679 | 1,457,647 | 94.2 | 90,032 | 5.8 | |

| 2011 | 1,441,703 | 1,336,346 | 92.7 | 105,357 | 7.3 | |

| 2012 | 1,623,346 | 1,497,811 | 92.3 | 125,535 | 7.7 | |

| 2013 | 2,125,506 | 1,964,853 | 92.4 | 160,653 | 7.6 | |

| 2014 | 1,908,993 | 1,751,049 | 91.7 | 157,944 | 8.3 | |

| LASER HAIR REMOVAL | 2005 | 1,566,909 | 1,334,669 | 85.2 | 232,240 | 14.8 |

| 2006 | 1,475,296 | 1,308,739 | 88.7 | 166,557 | 11.3 | |

| 2007 | 1,412,658 | 1,226,974 | 86.9 | 185,684 | 13.1 | |

| 2008 | 1,280,963 | 1,101,255 | 86.0 | 179,708 | 14.0 | |

| 2009 | 1,280,031 | 1,113,996 | 87.0 | 166,035 | 13.0 | |

| 2010 | 936,271 | 817,383 | 87.3 | 118,888 | 12.7 | |

| 2011 | 919,802 | 812,352 | 88.3 | 107,450 | 11.7 | |

| 2012 | 883,893 | 757,489 | 85.7 | 126,404 | 14.3 | |

| 2013 | 901,570 | 773,278 | 85.8 | 128,292 | 14.2 | |

| 2014 | 828,480 | 721,874 | 87.1 | 106,606 | 12.9 | |

| ABLATIVE LASER | 2005 | 475,689 | 432,606 | 90.9 | 43,083 | 9.1 |

| 2006 | 576,512 | 528,061 | 91.6 | 48,451 | 8.4 | |

| 2007 | 509,901 | 479,799 | 94.1 | 30,102 | 5.9 | |

| 2008 | 570,880 | 532,008 | 93.2 | 38,872 | 6.8 | |

| 2009 | 522,319 | 463,339 | 88.7 | 58,980 | 11.3 | |

| 2010 | 562,605 | 518,275 | 92.1 | 44,330 | 7.9 | |

| 2011 | 345,587 | 319,810 | 92.5 | 25,777 | 7.5 | |

| 2012 | 432,496 | 401,915 | 92.9 | 30,581 | 7.1 | |

| 2013 | 359,404 | 334,026 | 92.9 | 25,378 | 7.1 | |

| 2014 | 408,433 | 381,890 | 93.5 | 26,543 | 6.5 | |

| INTESE PULSED LIGHT | 2005 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 2006 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 2007 | 647,707 | 584,530 | 90.2 | 63,177 | 9.8 | |

| 2008 | 526,828 | 479,941 | 91.1 | 46,887 | 8.9 | |

| 2009 | 452,210 | 404,534 | 89.5 | 47,676 | 10.5 | |

| 2010 | 381,480 | 345,545 | 90.6 | 35,935 | 9.4 | |

| 2011 | 439,161 | 396,866 | 90.4 | 42,295 | 9.6 | |

| 2012 | 337,482 | 308,764 | 91.5 | 28,718 | 8.5 | |

| 2013 | 456,613 | 413,186 | 90.5 | 43,427 | 9.5 | |

| 2014 | 370,496 | 318,846 | 86.1 | 51,650 | 13.9 | |

| FRAXEL | 2005 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 2006 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 2007 | 167,351 | 153,954 | 92.0 | 13,397 | 8.0 | |

| 2008 | 110,392 | 103,468 | 93.7 | 6,924 | 6.3 | |

| 2009 | 119,676 | 109,091 | 91.2 | 10,585 | 8.8 | |

| 2010 | 102,016 | 94,003 | 92.1 | 8,013 | 7.9 | |

| 2011 | 100,433 | 92,719 | 92.3 | 7,714 | 7.7 | |

| 2012 | 86,313 | 75,349 | 87.3 | 10,964 | 12.7 | |

| 2013 | 90,801 | 83,490 | 91.9 | 7,311 | 8.1 | |

| 2014 | 84,833 | 75,589 | 89.1 | 9,244 | 10.9 | |

| NONINVASIVE TIGHTENING | 2005 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 2006 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 2007 | 258,236 | 239,168 | 92.6 | 19,068 | 7.4 | |

| 2008 | 257,995 | 232,594 | 90.2 | 25,401 | 9.8 | |

| 2009 | 275,118 | 264,366 | 96.1 | 10,752 | 3.9 | |

| 2010 | 247,500 | 236,588 | 95.6 | 10,912 | 4.4 | |

| 2011 | 297,795 | 279,549 | 93.9 | 18,246 | 6.1 | |

| 2012 | 350,353 | 318,196 | 90.8 | 32,157 | 9.2 | |

| 2013 | 388,311 | 342,277 | 88.1 | 46,034 | 11.9 | |

| 2014 | 433,671 | 395,581 | 91.2 | 38,090 | 8.8 | |

| SCLEROTHERAPY | 2005 | 554,252 | 548,045 | 98.9 | 6,207 | 1.1 |

| 2006 | 559,284 | 541,291 | 96.8 | 17,993 | 3.2 | |

| 2007 | 471,639 | 467,844 | 99.2 | 3,795 | 0.8 | |

| 2008 | 423,842 | 417,465 | 98.5 | 6,377 | 1.5 | |

| 2009 | 452,924 | 442,015 | 97.6 | 10,909 | 2.4 | |

| 2010 | 444,888 | 434,994 | 97.8 | 9,894 | 2.2 | |

| 2011 | 354,731 | 348,501 | 98.2 | 6,230 | 1.8 | |

| 2012 | 296,501 | 282,229 | 95.2 | 14,272 | 4.8 | |

| 2013 | 375,446 | 367,384 | 97.9 | 8,062 | 2.1 | |

| 2014 | 315,707 | 305,377 | 96.7 | 10,330 | 3.3 | |

| MICRODERMABRASION | 2005 | 1,023,931 | 939,508 | 91.8 | 84,423 | 8.2 |

| 2006 | 993,072 | 921,970 | 92.8 | 71,102 | 7.2 | |

| 2007 | 829,658 | 743,748 | 89.6 | 85,910 | 10.4 | |

| 2008 | 557,131 | 517,307 | 92.9 | 39,824 | 7.1 | |

| 2009 | 621,943 | 565,031 | 90.8 | 56,912 | 9.2 | |

| 2010 | 450,744 | 416,315 | 92.4 | 34,429 | 7.6 | |

| 2011 | 499,427 | 468,466 | 93.8 | 30,961 | 6.2 | |

| 2012 | 498,820 | 454,069 | 91.0 | 44,751 | 9.0 | |

| 2013 | 479,865 | 452,351 | 94.3 | 27,514 | 5.7 | |

| 2014 | 417,034 | 372,218 | 89.3 | 44,816 | 10.7 | |

| CHEMICAL PEELS | 2005 | 556,171 | 533,009 | 95.8 | 23,162 | 4.2 |

| 2006 | 558,430 | 530,147 | 94.9 | 28,283 | 5.1 | |

| 2007 | 575,081 | 536,044 | 93.2 | 39,037 | 6.8 | |

| 2008 | 591,808 | 554,492 | 93.7 | 37,316 | 6.3 | |

| 2009 | 528,285 | 492,335 | 93.2 | 35,950 | 6.8 | |

| 2010 | 493,806 | 469,570 | 95.1 | 24,236 | 4.9 | |

| 2011 | 384,222 | 360,313 | 93.8 | 23,909 | 6.2 | |

| 2012 | 443,824 | 418,774 | 94.4 | 25,050 | 5.6 | |

| 2013 | 444,268 | 412,870 | 92.9 | 31,398 | 7.1 | |

| 2014 | 484,053 | 452,872 | 93.6 | 31,181 | 6.4 |

Figure 1.

Percentage of total nonsurgical cosmetic procedures versus time for neurotoxin injections and soft tissue filler injections performed on men from 2005 through 2014. Data from The American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery procedure surveys.4–13

The National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) is a survey of office-based physicians across specialties. In 2007, Housman et al14 analyzed NAMCS data from 1995 to 2003 and found that dermatologists were performing more NSCPs than other specialists.14 Using ICD-9-CM procedure codes, these authors interrogated the data for cosmetic procedures including NSCPs. The authors’ analysis suggested that 21.3 percent of all NSCPs during this time were being performed on men (Table 2). Interestingly, these data suggest the most popular procedures for men in order were chemical peels, then soft tissue fillers, then dermabrasion. These observations stand in contrast to ASAPS data and common experience, both of which suggest neurotoxins followed by dermal fillers are the most popular NSCPs for men.13 These particular data are subject to the limitation of including only data for which ICD-9-CM codes were entered. A large number of cosmetic procedures are billed directly to the patient, rendering procedure codes unnecessary. Therefore, particular procedures that are more likely to be covered by insurance in part or in whole (e.g., scar rehabilitation) are more likely to be included in this survey than procedures paid for exclusively by the patient.

Table 2.

Gender-specific data on nonsurgical cosmetic procedures from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey pooled from 1995 to 2003. Data from Housman et al 2008.14

| PROCEDURE | TOTAL NUMBER | TOTAL % | NUMBER WOMEN | % WOMEN | NUMBER MEN | % MEN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHEMICAL PEELS | 2,706,802 | 28.8 | 1,796,168 | 66.4 | 910,635 | 33.6 |

| DERMAL FILLER | 2,570,137 | 27.3 | 1,814,297 | 70.6 | 755,841 | 29.4 |

| SCLEROTHERAPY | 1,803,140 | 19.2 | 1,715,284 | 95.1 | 87,856 | 4.9 |

| NEUROTOXIN | 746,079 | 7.9 | 720,977 | 96.6 | 25,102 | 3.4 |

| EPILATION | 383,499 | 4.1 | 377,920 | 98.5 | 5,578 | 1.5 |

| DERMABRASION | 1,172,808 | 12.5 | 953,865 | 81.3 | 218,943 | 18.7 |

| COLLAGEN | 19,524 | 0.2 | 19,524 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| TOTAL | 9,401,989 | 100 | 7,398,035 | 78.7 | 2,003,954 | 21.3 |

The ASDS surveys dermatologists annually on the number of procedures they are performing. Gender-specific data are available only for neurotoxins and dermal fillers from 2011 through 2014, and these data are summarized in Table 3.1,15–17 In summary, the data show that the percentage of neurotoxin injections performed on men increased from 10 percent in 2011 to 13 percent in 2014, whereas the percentage of soft tissue filler procedures performed on men increased from eight to only nine percent over the same time interval. In accordance with the ASAPS data, these results suggest that the percentage of men seeking neuromodulator injections is increasing more rapidly than that for other NSCPs.

Table 3.

Table 3. Gender-specific data on nonsurgical cosmetic procedures from The American Society for Dermatologic Surgery procedure survey from 2011 through 20141,15–17

| YEAR | TOTAL | FEMALE NUMBER | FEMALE % | MALE NUMBER | MALE % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEUROTOXIN | 2011 | 1,200,000 | 1,080,000 | 90 | 120,000 | 10 |

| 2012 | 1,493,147 | 1,328,901 | 89 | 164,246 | 11 | |

| 2013 | 1,800,000 | 1,602,000 | 89 | 198,000 | 11 | |

| 2014 | 1,740,000 | 1,513,800 | 87 | 226,200 | 13 | |

| FILLERS | 2011 | 830,800 | 764,336 | 92 | 66,464 | 8 |

| 2012 | 916,455 | 843,139 | 92 | 73,316 | 8 | |

| 2013 | 995,000 | 895,500 | 90 | 99,500 | 10 | |

| 2014 | 1,010,000 | 919,100 | 91 | 90,900 | 9 |

The 2013 International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (ISAPS) procedure survey, including data from 10 nations, indicated that men comprise 11.3 percent of those undergoing NSCPs (Table 4).18 Men made up the largest percentage of those seeking laser hair removal (15.1%), followed by neurotoxin injection (12.5%). Men made up the smallest percentage (6.4%) of those obtaining noninvasive facial rejuvenation procedures such as intense pulsed light. Data from previous years is not available for review.

Table 4.

Gender-specific data on nonsurgical cosmetic procedures from the International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery 2013 procedure survey18

| PROCEDURE | TOTAL | TOTAL % | TOTAL FEMALE | FEMALE % | TOTAL MALE | MALE % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEUROTOXIN | 5,145,189 | 43.3 | 4,501,514 | 87.5 | 643,675 | 12.5 |

| CHEMICAL PEEL, CO2 RESURFACING, DERMABRASION | 773,442 | 6.5 | 682,647 | 88.3 | 90,795 | 11.7 |

| NONABLATIVE REJUVENATION | 1,307,300 | 11.0 | 1,223,520 | 93.6 | 83,780 | 6.4 |

| FILLERS | 3,089,686 | 26.0 | 2,787,799 | 90.2 | 301,887 | 9.8 |

| LASER HAIR REMOVAL | 1,440,253 | 12.1 | 1,222,720 | 84.9 | 217,533 | 15.1 |

| SCLEROTHERAPY | 119,040 | 1.0 | 109,771 | 92.2 | 9,269 | 7.8 |

| TOTAL | 11,874,910 | 100 | 10,527,971 | 88.7 | 1,346,939 | 11.3 |

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS FOR MALE PATIENTS UNDERGOING NSCPs

There are significant anatomical, physiological, and behavioral differences in the aging male face that warrant specific treatment considerations. For example, men have more skeletal musculature than their female counterpart19 and this likely extends to mimetic musculature given that men have more facial muscular movement than women.20 These observations may explain why men tend to generally have more exuberant dynamic facial rhytids than women21 in areas other than the perioral area.22 Non-facial skin is thicker in males and has a higher collagen content than in females.23 These findings likely extend to facial skin. Men also tend to have more sebaceous skin and may therefore be more inclined to seek treatment for sebaceous hyperplasia. Men have greater vascularity and perfusion of facial skin, which may carry implications for complications of NSCPs,24 such as bleeding and bruising.

There are gender-specific differences in facial bone structure. In particular, men have a more prominent supraorbital rim, a larger forehead, and flatter cheeks that are more angular.25 Men also have a greater forehead slope from brow to hairline, a flatter brow, and a more defined hairline with a wider and more forwardly projected chin.26 These anatomic differences are of paramount consideration in the context of cosmetic interventions, as exaggeration rather than restoration of typical male features can result in an aggressive or threatening appearance, whereas accentuation of feminine features will have a feminizing effect.26

In addition to considerations of gender-specific anatomical and physiological considerations, behavioral and psychological factors must also be considered when addressing cosmetic concerns of male patients. Men, like women, find facial symmetry desirable.27 However, men often do not desire complete eradication of dynamic rhytids, preferring instead to have them softened.26 Men may also be less inclined to request procedures associated with downtime such as fully ablative resurfacing,28 perhaps due to a combination of social stigmatization and career issues. Men also tend to be more conservative and tend to elect for only one procedure at a time, particularly with their first treatment sessions.28 Although it has not yet been studied, a higher percentage of male cosmetic patients may be naïve and may therefore have a less clear understanding of procedures from which they may benefit. Regardless of current trends, men still make up a small minority of those seeking NSCPs, so they are less likely to have heard about specific procedures from same-gender peers. It is therefore possible that new male cosmetic patients may require more counseling than their female counterparts.

Clinics with a specific understanding of male NSCP patients can foster an environment with which these patients will be comfortable and in which they will achieve desirable outcomes. Such clinics may serve to destigmatize NSCPs among some men who may still believe that these procedures are “only for women.” However, caution must be used to avoid creating spaces that feel hypermasculine for this would have the potential to alienate some patients.

GENDER-SPECIFIC APPROACH FOR NONSURGICAL COSMETIC PROCEDURES FOR MALE PATIENTS

Data suggests that men seek treatment with nonablative fractional resurfacing devices for different indications than do women. According to one study, the most common indications for men in decreasing order were acne scars, facial photoaging, and traumatic/surgical scars.29 In contrast, the most common indications for women were facial photoaging, non-facial photoaging, and acne scars in descending order. Anecdotal evidence also suggests that men are less likely than their female counterparts to seek more than one cosmetic treatment per visit, in particular for their initial treatment.28 Men also tend to be less patient and expect immediate results, yet do not tolerate post-procedure edema and erythema and are relatively unwilling to use masking agents such as make-up, but also tend to have fewer post-procedure acne flares than women.28 One author has reported the use of devices, such as the 590nm LED, to reduce post-procedure erythema and edema to minimize downtime after photorejuvenation with nonablative lasers in men.28 The same author advocates using higher fluences with men than with women, perhaps owing to some of the aforementioned gender-specific differences in anatomy and physiology of skin. Another technique the authors’ group commonly employs is use of a single application of a high potency topical corticosteroid immediately after the procedure to reduce post procedure erythema and edema.

Careful consideration of male facial anatomy is essential for patients seeking injection of dermal fillers. For example, outcomes may be more favorable when men are injected with volumizing filler in the lateral face (i.e., zygomatic cheek), as filler injected in the central face tends to be more feminizing. Also, the increased vascularity in the beard area of the male face suggests that men may be more prone to bruising following injections of filler for neurotoxin into the lower face.24,25,30

There are numerous gender-specific differences in facial anatomy that render special attention to technique absolutely essential for men requesting neurotoxin injections. Many of these differences have been reviewed elsewhere,26,30,31 so the present discussion will highlight solely a few salient points. Men tend to have larger foreheads, often resulting in the need for more injection sites. Men also tend to have brows that are low by nature, so injections that are too low or potent can easily result in ptosis.30 The male brow also tends to be flatter than that in women, so when choosing injection sites, care must be taken to avoid central or lateral brow lift.30 While there is at present no data to suggest that men require significantly more units of neurotoxin to successfully treat forehead rhytids, a randomized, double-blind study showed that men may require as much as 40 to 80 units of onabotulinumA to successfully treat glabellar rhytids, and that these high doses are not associated with an increased risk of complications.32 With treatment of the glabellar complex and resulting chemodenervation of the medial frontalis, there can be recruitment of lateral frontalis resulting in lateral brow lift.31 This is generally an undesirable outcome in males as it results in an eyebrow arch that is more typical of the female brow. Fortunately, this can be corrected or anticipated by treating the lateral frontalis at the same time as the glabellar complex.31 Moreover, the orbicularis oculi extends more laterally in men, so additional lateral depots may be required when treating lateral canthal folds.31

DISCUSSION

Men are showing increasing interest in NSCPs, perhaps more so than in surgical cosmetic interventions for which interest among males may not be rising as rapidly.33 The ASAPs survey data reviewed here suggest that the percentage of all NSCPs performed on men is slowly trending upward, implying that the male cosmetic sector is growing more rapidly than the female sector. Much of this trend is likely attributable to the high rate of growth of neurotoxin injections, which were the most popular NSCP requested by men in a survey series (Table 1). The ASDS survey results also suggested that rates of neurotoxin injections are on the rise among men, whereas filler injection rates are increasing modestly, if at all. All three surveys reviewed suggest that men comprise approximately10 to 20 percent of individuals seeking NSCPs, which is consistent with rates at our practice. It therefore bears emphasizing that while the male sector of this industry is increasing, males still make up a small minority of those pursuing these procedures.

There are likely numerous reasons why men are increasingly seeking out NSCPs. The overall trend regardless of gender is toward more NSCPs, and this is likely associated with societal destigmatization. Further, while in recent years there have been “reality” television programs that have shown cast members undergoing procedures, there are currently on-air several programs that focus specifically on cosmetic procedures. In addition to the societal destigmatization, it is possible that an additional contributing factor is the movement of so-called “metrosexuals”— progressive young urban heterosexual men who are meticulous about their appearance, a trait that had historically been attributed to women and homosexual men.34 It is plausible that men self-identifying as “metrosexual” may be over-represented among those seeking NSCPs, but this has not yet been studied.

Future studies should aim to further characterize this segment of the NSCP market with behavioral surveys. Further, the data reviewed here are merely semiquantitative, meaning there is still a need for systematic studies that will allow a more accurate characterization of these trends over time. One significant limitation of survey data is that changes in survey protocols may be altered from year to year, rendering comparisons across survey years problematic. Despite these limitations, the data reviewed here consistently suggest that men are increasingly interested in NSCPs. Clinics treating a large number of male cosmetics patients need to be aware of not only the gender-specific anatomical and physiological considerations reviewed here, but also the behavioral and psychological attributes specific to the population comprising this burgeoning niche.

Footnotes

Disclosure:Dr. Frucht reports no relevant conflicts of interest. Dr. Ortiz is an Allergan stockholder; has received equipment loans from Zeltiq, Sciton, Solta, Inmode, and BTL; and is an advisory board member for Inmode and Sciton.

REFERENCES

- 1. [Accessed on May 25, 2015]. http://www.asds.net/WorkArea/linkit.aspx?LinkIdentifier=id&ItemID=7758&libID=7733 American Society for Dermatologic Surgery 2013 survey on dermatologic procedures.

- 2.Miner MM, Perelman MA. A psychological perspective on male rejuvenation. Fertility and Sterility. 2013;99:1803–1806. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daines SM, Mobley SR. Considerations in male aging face consultation: psychologic aspects. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2008;16:281–287. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2008.03.001. v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. [Accessed May 2015]. http://www.surgery.org/media/statistics American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery 2005 statistics on cosmetic surgery.

- 5. [Accessed May 2015]. http://www.surgery.org/media/statistics American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery 2006 statistics on cosmetic surgery.

- 6. [Accessed May 2015]. http://www.surgery.org/media/statistics American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery 2007 statistics on cosmetic surgery.

- 7. [Accessed May 2015]. http://www.surgery.org/media/statistics American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery 2008 statistics on cosmetic surgery.

- 8. [Accessed May 2015]. http://www.surgery.org/media/statistics American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery 2009 statistics on cosmetic surgery.

- 9. [Accessed May 2015]. http://www.surgery.org/media/statistics American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery 2010 statistics on cosmetic surgery.

- 10. [Accessed May 2015]. http://www.surgery.org/media/statistics American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery 2011 statistics on cosmetic surgery.

- 11. [Accessed May 2015]. http://www.surgery.org/media/statistics American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery 2012 statistics on cosmetic surgery.

- 12. [Accessed May 2015]. http://www.surgery.org/media/statistics American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery 2013 statistics on cosmetic surgery.

- 13. [Accessed May 2015]. http://www.surgery.org/media/statistics American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery 2014 statistics on cosmetic surgery.

- 14.Housman TS, Hancox JG, Mir MR, et al. What specialties perform the most common outpatient cosmetic procedures in the United States? Dermatol Surg. 2008p;34:1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.34000.x. discussion 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. [Accessed on May 25, 2015]. http://www.asds.net/Survey-results/ American Society for Dermatologic Surgery 2011 survey on dermatologic procedures.

- 16. [Accessed on May 25, 2015]. http://www.asds.net/WorkArea/linkit.aspx?Link Identifier=id&ItemID=6655&libID=6631 American Society for Dermatologic Surgery 2012 survey on dermatologic procedures.

- 17.American Society for Dermatologic Surgery; 2014. American Society for Dermatologic Surgery 2014 survey on dermatologic procedures. [Google Scholar]

- 18. [Accessed May 2015]. http://www.isaps.org/Media/Default/global-statistics/2014%20ISAPS%20Results%20(3).pdf International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery 2013 Procedure Survey.

- 19.Janssen I, Heymsfield SB, Wang ZM, Ross R. Skeletal muscle mass and distribution in 468 men and women aged 18–88 yr. J Appl Physiol. 2000;89:81–88. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.89.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weeden JC, Trotman CA, Faraway JJ. Three dimensional analysis of facial movement in normal adults: influence of sex and facial shape. Angle Orthod. 2001;71:132–140. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2001)071<0132:TDAOFM>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsukahara K, Hotta M, Osanai O, et al. Gender-dependent differences in degree of facial wrinkles. Skin Res Technol. 2013;19:e65–e71. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0846.2011.00609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paes EC, Teepen HJ, Koop WA, Kon M. Perioral wrinkles: histologic differences between men and women. Aesthet Surg J. 2009;29(6):467–472. doi: 10.1016/j.asj.2009.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shuster S, Black MM, McVitie E. The influence of age and sex on skin thickness, skin collagen and density. Br J Dermatol. 1975;93:639–643. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1975.tb05113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mayrovitz HN, Regan MB. Gender differences in facial skin blood perfusion during basal and heated conditions determined by laser Doppler flowmetry. Microvasc Res. 1993;45:211–218. doi: 10.1006/mvre.1993.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keaney T. Male aesthetics. Skin Therapy Lett. 2015;20:5–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rossi AM. Men’s aesthetic dermatology. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2014;33:188–197. doi: 10.12788/j.sder.0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grammer K, Thornhill R. Human (Homo sapiens) facial attractiveness and sexual selection: the role of symmetry and averageness. J Comp Psychol. 1994;108:233–242. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.108.3.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ross EV. Nonablative laser rejuvenation in men. Dermatol Ther. 2007;20:414–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2007.00157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Narurkar VA. Nonablative fractional resurfacing in the male patient. Dermatol Ther. 2007;20:430–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2007.00173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keaney TC, Alster TS. Botulinum toxin in men: review of relevant anatomy and clinical trial data. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1434–1443. doi: 10.1111/dsu.12302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Flynn TC. Botox in men. Dermatol Ther. 2007;20:407–413. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2007.00156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carruthers A, Carruthers J. Prospective, double-blind, randomized, parallel-group, doseranging study of botulinum toxin type A in men with glabellar rhytids. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:1297–1303. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2005.31206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holcomb JD, Gentile RD. Aesthetic facial surgery of male patients: demographics and market trends. Facial Plast Surg. 2005;21:223–231. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-939501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheng F, Ooi C, Ting D. Factors affecting consumption behavior of metrosexual toward male grooming products. International Review of Business Research Papers. 2010;6(1):574–590. [Google Scholar]