Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the impact of a population-based telephonic wellness coaching program on weight loss.

Methods

Individual-level segmented regression analysis of interrupted time series data comparing the BMI trajectories in the 12 months before vs. the 12 months after initiating coaching among a cohort of Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) members (n=954) participating in The Permanente Medical Group (TPMG) Wellness Coaching program in 2011. The control group was a 20:1 propensity-score matched control group (n=19,080) matched with coaching participants based on baseline demographic and clinical characteristics.

Results

Wellness coaching participants had a significant upward trend in BMI in the 12 months before their first Wellness coaching session, and a significant downward trend in BMI in the 12 months after their first session equivalent to a clinically significant reduction of greater than one unit of baseline BMI (p<.01 for both). The control group did not have statistically significant decreases in BMI during the post-period.

Conclusions

Wellness coaching has a positive impact on BMI reduction that is both statistically and clinically significant. Future research and quality improvement efforts should focus on disseminating Wellness coaching for weight loss in diabetes patients and those at risk for developing the disease.

Keywords: Health promotion, health coaching, wellness coaching, BMI, weight loss

Introduction

Recent national estimates suggest that more than two-thirds (68.8%) of adult Americans are above normal weight: more than one third of the population consists of people with obesity, and more than 1 in 20 have a body mass index (BMI) >= 40kg/m2.(1, 2) This may increase the risk of developing type 2 diabetes, heart disease, high blood pressure, stroke, and some types of cancer within individuals. (3, 4) Among patients with diabetes, populations with overweight or obesity may also have higher rates of diabetes complications. (5-7)

Although obesity is an epidemic in the U.S., there are very few health plan-based programs designed to promote weight loss at the population level. Telephone-based, or telephonic, wellness coaching programs may help to address excess weight gain by encouraging healthy lifestyle choices. (8) Telephonic wellness coaching is often delivered by non-physician health care providers such as nurses, and gives patients the support, information, and skills to improve their self-efficacy and make patient-directed positive changes in health behaviors.(9-13) Randomized controlled trials testing the efficacy of coaching have suggested that patients who participate in telephonic coaching may achieve small but significant weight loss, (8, 14-16) and other studies have suggested that health coaching can improve outcomes for patients with chronic diseases, (12, 17) and reduce medical cost and hospitalization.(18). Despite its potential positive impact on weight loss, telephonic wellness coaching has not been widely adopted as an obesity intervention, and there is very little evidence on how to integrate meaningful weight loss into routine clinical practice (19-21) where it may be most effective. (22) While some community-based coaching programs conducted by research teams have been evaluated (14, 23-24), there are no evaluations of the effectiveness of real-world wellness coaching programs on weight loss when implemented across a health care delivery system.

The purpose of this study is to conduct an evaluation of The Permanente Medical Group (TPMG) telephonic Wellness Coaching program on 12-month weight loss among patients who initiated the program to address weight, exercise, and healthy eating concerns.

Methods

Study Setting and Coaching Program Description

Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) is an integrated health care delivery system currently serving approximately 3.8 million members in Northern California. KPNC membership is diverse, community-based, and broadly representative of the local and statewide population. The Permanente Medical Group (TPMG) is a multidisciplinary medical group that provides programs and direct care to KPNC members. Since 2010, TPMG has provided a telephonic wellness coaching program which supports patients’ efforts to change behaviors related to weight management, healthy eating, physical activity, tobacco cessation, and stress reduction. The Wellness Coaching program has been described in detail elsewhere. (9, 10, 25, 26) In brief, during the first coaching session (approximately 20-30 minutes in length), patients speak to their wellness coach on the telephone, decide on a health topic on which to focus, assess readiness to change, and choose an action step to begin; follow-up sessions are typically 10-15 minutes in length scheduled on an ad hoc basis upon request, and are intended to be completed within a year or less. Wellness coaches are TPMG master’s-level clinical health educators who are trained in motivational interviewing strategies, a patient-centered counseling style that engages intrinsic motivation within the patient to change behavior.(27) Members are connected to participate in the Wellness Coaching program through referrals by TPMG providers and staff, and partnerships with employers; patients may also self-refer if they learned about the coaching program through any of these methods, from fellow patients, or from their medical facility. Wellness coaching is a covered benefit, and is offered as a covered benefit to all KPNC members.

Study participants

We examined all adults who initiated telephonic coaching between January 1 and August 23 2011 (n=1,539), and selected those who contacted coaching regarding a topic directly related to BMI (i.e., weight management, healthy eating, and physical activity) (n=1,183). We limited our analyses to those who had non-missing data for the propensity score matching variables described below (n=1,173), those with no pregnancy recorded during their observation window (n=1,139), and who had a valid BMI observation in the year leading up to and the year after the initiating coaching session (n=954). The index date for the coaching participants was the date of their first coaching session.

We used propensity score matching to select a control group not exposed to wellness coaching from the population of KPNC members who were in the age range of the coaching participants (18-90 years), whose primary language was recorded as English or Spanish, and who had non-missing data for the variables used in the propensity score described below. Propensity for participating in wellness coaching was calculated from a logistic regression model with the following variables: age, gender, race/ethnicity, annual number of primary care visits in previous year, home service area, current tobacco use, health risk and comorbidities as measured by the Diagnostic Cost Group (DxCG) score (28,29), and the patient’s 12 month BMI trajectory as the patient’s average BMI in each of the four quarters in the year before the index date (4 BMI observations total). For quarters without a BMI observation, we used the last observation carried forward or next observation carried backward; this proportion of 20% did not differ between the participant and control groups (data not shown). As the index dates of the coaching participants spanned three quarters of 2011 and the propensity score model included time-varying measures (e.g., most recent BMI in each of the 4 quarters, number of primary care visits in the previous year), we generated propensity scores for the eligible controls for each quarter of the study using data relative to the first day of the quarter. Using propensity score matching with the nearest neighbor without replacement method, for each coaching participant we identified 20 matched controls that were not exposed to wellness coaching; this number was chosen to maximize the availability of potential controls while also maximizing efficiency. (30) The index date for the participants was set at the date they started the program; matched controls was defined as the first day of the quarter for which they were matched.

Main Outcome Measure and Data Sources

All data for this study were derived from the KPNC electronic health record (EHR) and administrative databases. Weight, height, and BMI (kg/m2) are measured, recorded and calculated at each office visit, and this information is placed in the EHR. If a patient had more than one BMI recorded on the same day, the mean BMI was used for that day. All observed BMI values in the year before and year after the index date were used to model BMI trajectories.

Statistical Methods

We modeled BMI trends for the coaching participants and the matched controls using segmented linear regression analysis of interrupted times series data, a variation of standard linear regression analysis that estimates the slope in the year before the index date separately from the slope in the year after (31-34). The model included a linear time trend and a term to estimate the slope change at the index date. To test for differences between the coaching participants and the matched controls, the model further included an indicator for group, the interaction between the group indicator and the time trend, and the interaction between the group indicator and the term to estimate the slope change at the index date. The model used individual-level data and adjusted for the correlation among BMI measurement within patients. As a sensitivity analysis, we calculated the BMI unit change and weight change for each individual, and compared this average between the two groups.

Pearson chi-square tests of independence and two sample t tests were used to compare the baseline characteristics of the coaching participants and the control group. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.3. (35) These analyses were conducted under the auspices of the “Natural Experiments for Translation in Diabetes (NEXT-D) Study”; the KPNC Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Results

A total of 954 coaching participants met the inclusion criteria for this study. Coaching participants were majority white (52%) and predominately female (83%). The mean age for coaching participants was 52 years old, and the mean BMI was 34.5 kg/m2. There were no significant differences between coaching participants and the matched control group on age, gender, race/ethnicity, primary language, baseline BMI, pre-index date BMI slope, current tobacco use, percentage with a diabetes diagnosis at baseline, and DxCG risk score; there was a small but statistically significant difference in the mean number of primary care visits (4.3. vs. 4.0, p=.03). The mean number of telephonic coaching visits for program participants was 1.8 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Wellness Coaching participants and Propensity-score Matched Controls

| Coaching participants (n=954) |

Matched Controls (n=19,080) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 52 (14) | 51 (17) | .16 |

| Female, % | 83% | 86% | .07 |

| Race/ethnicity, % | .74 | ||

| Asian | 9% | 8% | |

| Black | 18% | 18% | |

| Hispanic | 18% | 19% | |

| White | 52% | 51% | |

| Other | 4% | 5% | |

| Primary language, % | .61 | ||

| English | 95% | 95% | |

| Spanish/Other | 5% | 5% | |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 34.5 (8.4) | 34.3 (9.4) | .57 |

| Current tobacco user, % | 4% | 4% | .77 |

| No. of primary care visits, mean (SD) | 4.3 (4.2) | 4.0 (4.7) | .03 |

| Diagnostic cost group (DxCG) risk score, mean (SD) |

2.9 (2.9) | 2.7 (3.2) | .08 |

| Diabetes Diagnosis, % | 16.8 | 17.2 | .71 |

| Pre-Index Date BMI Slope | 1.78 | 0.87 | .09 |

| Mean number of Coaching Sessions | 1.8 (1.1) | n/a | |

| Mean number of Days Between First and Last Coaching Sessions (SD) |

42.0 (58.3) | n/a | |

| Percent of Patients with >= 1 unit of BMI loss in the post period |

30.1 | 22.5 | <.01 |

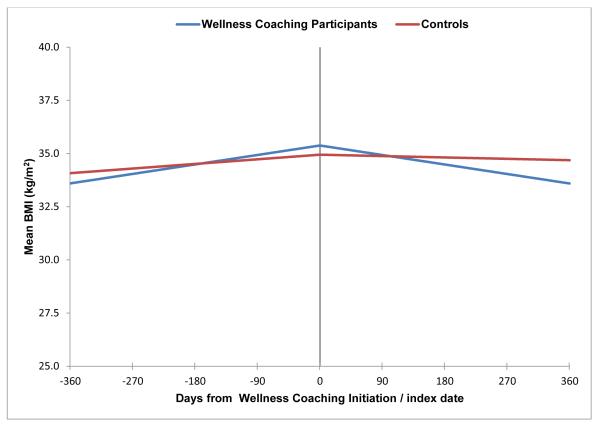

Table 2 and Figure 1 show the results of segmented linear regression analysis of interrupted time series data. The trajectory of patient BMI, or the slope, before the start of coaching was significantly positive for both participants exposed to wellness coaching and their matched controls who were not exposed to coaching, indicating both groups were gaining weight before the index date. There was no significant difference in this positive slope prior to the index date between the two groups (p=0.09). The BMI trajectory after the start of wellness coaching was negative for coaching program participants (−1.79 kg/m2, p<0.001), indicating a significant change in BMI that translates to weight loss 12 months after coaching initiation. The matched controls did not have a decrease in BMI (slope −0.26, p=0.11), and the difference in the post-index date slopes for the two groups was statistically significant (p=.002).

Table 2.

Slope of one-year trajectory in BMI for Wellness Coaching participants and Controls

| Estimate | 95% Confidence Interval |

P value (comparing slope to 0) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Slope before index | |||

| Wellness Coaching Participants | 1.78 | (0.77, 2.79) | <.001 |

| Matched Controls | 0.87 | (0.58, 1.15) | <.001 |

| Difference in slope between Wellness Coaching Participants and Matched controls |

0.91 | (−0.13, 1.96) | .09 |

| Slope after index | |||

| Wellness Coaching Participants | −1.79 | (−2.68, −0.90) | <.001 |

| Matched Controls | −0.26 | (−0.58, 1.15) | .11 |

| Difference between Wellness Coaching Participants and Matched Controls |

−1.53 | (−2.47, −0.58) | .002 |

Figure 1. BMI trends for pre- and post-exposure to Wellness Coaching and pre- and post-index date for controls*.

* Statistically significant difference in weight trajectories after index.

Our sensitivity analysis showed that the BMI unit change and the weight change for each individual averaged across groups was statistically significantly lower in coaching participants compared to controls (data not shown).

Discussion

Obesity is a major health issue in the U.S., increasing the risks of developing diabetes and the risks of micro- and macro-vascular complications in diabetes patients. Behavioral interventions within clinical settings may be an important means for addressing unhealthy behaviors. (36) This study was designed to evaluate the impact of a real-world telephonic wellness coaching program on weight loss among patients whose goals were to manage their weight, improve their healthy eating habits, or increase their physical activity. Among wellness coaching participants, we found a significant downward trajectory in BMI over a 12 month period starting from the first coaching session, compared with matched controls that were not exposed to coaching, and an estimated level of BMI reduction of greater than one unit, which is considered clinically significant in populations with overweight and obesity. (37) These results are comparable to those of clinical trials of coaching interventions, (19, 20) suggesting that telephonic coaching programs can be effective when adopted as part of routine clinical care. Telephonic wellness coaching that is implemented as a part of routine health care and made accessible to health plan populations may provide effective weight loss support at the population level.

The wellness coaching model delivered by TPMG is based on motivational interviewing, which is a patient-centered and evidence-based approach to behavior change.(10, 38) While the coaching program does not require use of a standardized guidebook or educational content for the coaching sessions, patients are provided with the opportunity to receive evidence-based Kaiser Permanente-branded health education materials relevant to their coaching topics of interest. This study adds to the evidence that motivational interviewing combined with evidence-based health education information is an effective approach to weight loss by demonstrating the positive impact of the coaching program on weight loss. Studies have been shown that motivational interviewing is more effective than other more directive or educational-based interventions. (39) This coaching program resulted in an average of approximately two encounters per participant; prior research suggests that low-intensity interventions based on motiviational interviewing such as this one can be effective across a range of health behavior outcomes (40). Our results suggest that using a motivational interviewing-based approach in population-based preventive and care programs can be an important strategy for helping patients achieve a healthy weight, and potentially improving health care outcomes.

This study has several limitations. Individuals were not randomized to participate in coaching, and the participation rate in the program was relatively low compared to the size of the general KPNC membership; there may be differences in motivation between patients who selected wellness coaching versus matched control group for in these analyses which could not be balanced out through propensity score matching. Socioeconomic status, which may also differ between coaching participants vs. controls, was also not available for use in the propensity score models. However, our propensity scores used a wide range of variables available in the electronic health records. While this program was made available to all KPNC members, a relatively small percentage of KPNC members took advantage of the program in its early years. Future research should continue to explore the most effective means for encouraging participation in telephonic wellness coaching among patients seeking to lose weight to improve their health and well-being. (23)

Conclusion

Telephonic wellness coaching programs implemented within health care delivery systems may help to provide effective weight loss support to the broader population, and reduce the rates of chronic disease and health complications related to excess weight gain. Future research should assess the effectiveness of other real-world weight loss programs, and examine how to disseminate and spread effective weight loss programs on a wide scale.

What is important about the subject?

Telephonic wellness coaching can be an important strategy for achieving weight loss, but little is known about the effectiveness of such programs at the population level.

What does this study add?

Our study demonstrates the effectiveness of a real-world coaching program in helping patients achieve clinically meaningful weight loss compared to matched controls.

These findings are an important addition to the evidence base that health plan-level programs can help patients achieve a healthy weight, and improve health care outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the editorial contributions of Hong Xiao, MD and Karen Estacio.

Funding: This study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institute for Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) (grant no. U58 DP002721). Drs. Ferrara and Schmittdiel were also supported by the Health Delivery Systems Center for Diabetes Translational Research NIDDK grant 1P30-DK092924). Dr. Brown was also supported by the NIDDK (grant no. K01 099404).

Footnotes

Disclosure: Dr. Goler is affiliated with the TPMG Wellness Coaching Center. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.National Institutes of Health (NIH) Overweight and Obesity Statistics. Bethesda, MD: [cited 2015 December 15]. 2012. Available from: http://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-statistics/Pages/overweight-obesity-statistics.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011-2012. JAMA. 2014 Feb 26;311(8):806–14. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999-2008. JAMA. 2010 Jan 20;303(3):235–41. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malnick SD, Knobler H. The medical complications of obesity. QJM. 2006 Sep;99(9):565–79. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcl085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klein R, Klein BE, Moss SE. Is obesity related to microvascular and macrovascular complications in diabetes? The Wisconsin Epidemiologic Study of Diabetic Retinopathy. Arch Intern Med. 1997 Mar 24;157(6):650–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Straub RH, Thum M, Hollerbach C, Palitzsch KD, Scholmerich J. Impact of obesity on neuropathic late complications in NIDDM. Diabetes Care. 1994 Nov;17(11):1290–4. doi: 10.2337/diacare.17.11.1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bergstrom B, Lilja B, Osterlin S, Sundkvist G. Autonomic neuropathy in non-insulin dependent (type II) diabetes mellitus. Possible influence of obesity. J Intern Med. 1990 Jan;227(1):57–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1990.tb00119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tao MRK, Paustian ML, Wasilevich EA, El Reda DK. Dialing in: effect of telephonic wellness coaching on weight loss. Am J Manag Care. 2014 Feb 1;20(2):e35–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adams SR, Goler NC, Sanna RS, et al. Patient satisfaction and perceived success with a telephonic health coaching program: the Natural Experiments for Translation in Diabetes (NEXT-D) Study, Northern California, 2011. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E179. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.130116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmittdiel JA, Brown SD, Neugebauer R, et al. Peer Reviewed: Health-Plan and Employer-Based Wellness Programs to Reduce Diabetes Risk: The Kaiser Permanente Northern California NEXT-D Study. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10 doi: 10.5888/pcd10.120146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Butterworth S, Linden A, McClay W, Leo MC. Effect of motivational interviewing-based health coaching on employees' physical and mental health status. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2006;11(4):358. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.11.4.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olsen JM, editor. Health Coaching: A Concept Analysis. Nurs Forum. 2014;49(1):18–29. doi: 10.1111/nuf.12042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bennett H, Laird K, Margolius D, Ngo V, Thom DH, Bodenheimer T. The effectiveness of health coaching, home blood pressure monitoring, and home-titration in controlling hypertension among low-income patients: protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2009;9(1):456. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hersey JC, Khavjou O, Strange LB, et al. The efficacy and cost-effectiveness of a community weight management intervention: a randomized controlled trial of the health weight management demonstration. Prev Med. 2012 Jan;54(1):42–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Terry PE, Seaverson EL, Grossmeier J, Anderson DR. Effectiveness of a worksite telephone-based weight management program. Am J Health Promot. 2011 Jan-Feb;25(3):186–9. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.081112-QUAN-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sangster J, Furber S, Allman-Farinelli M, et al. Effectiveness of a pedometer-based telephone coaching program on weight and physical activity for people referred to a cardiac rehabilitation program: a randomized controlled trial. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2015 Mar-Apr;35(2):124–9. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0000000000000082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huffman MH. Health coaching: a fresh, new approach to improve quality outcomes and compliance for patients with chronic conditions. Home Healthcare Nurse. 2009;27(8):490–6. doi: 10.1097/01.NHH.0000360924.64474.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wennberg DE, Marr A, Lang L, O'Malley S, Bennett G. A randomized trial of a telephone care-management strategy. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(13):1245–55. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0902321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sherman R, Crocker B, Dill D, Judge D. Health coaching integration into primary care for the treatment of obesity. Glob Adv Health Med. 2013 Jul;2(4):58–60. doi: 10.7453/gahmj.2013.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Appel LJ, Clark JM, Yeh HC, et al. Comparative effectiveness of weight-loss interventions in clinical practice. N Engl J Med. 2011 Nov 24;365(21):1959–68. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Merrill RM, Aldana SG, Bowden DE. Employee weight management through health coaching. Eat Weight Disord. 2010 Mar-Jun;15(1-2):e52–9. doi: 10.1007/BF03325280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patja K, Absetz P, Auvinen A, et al. Health coaching by telephony to support self-care in chronic diseases: clinical outcomes from The TERVA randomized controlled trial. BMC Health Services Research. 2012;12(1):147. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goode A, Reeves M, Owen N, Eakin E. Results from the dissemination of an evidence-based telephone-delivered intervention for healthy lifestyle and weight loss: the Optimal Health Program. Transl Behav Med. 2013;3(4):340–50. doi: 10.1007/s13142-013-0210-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goode AD, Winkler EA, Reeves MM, Eakin EG. Relationship between intervention dose and outcomes in living well siwht diabetes – a randomized trial of a tellephone-delivered lifestyle-based weight loss intervention. Am J Health Promot. 2015 Nov-Dec;30(2):120–9. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.140206-QUAN-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hong X, Boccio M, Sanna RS, Adams SR, Goler NC, Brown SD, Neugebauer RS, Ferrara A, Bellamy DJ, Schmittdiel JA. Wellness coaching for pre-diabetes patients: A randomized encouragement trial to evaluate outreach methods at Kaiser Permanente Northern California. Prev Chronic Dis. 2015 Nov 25;12:E207. doi: 10.5888/pcd12.150251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boccio M, Sanna RS, Adams SR, et al. Telephone-Based Coaching: A Comparison of Tobacco Cessation Programs in an Integrated Health Care System. Am J Health Promot. 2015 Nov 11; [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change, 3rd Edition (Applications of Motivational Interviewing) 3rd ed The Guilford Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baldwin L, Klabunde CN, Green P, Barlow W, Wright G. In search of the perfect comorbidity measure for use with administratiave claims data: does it exist? Med Care. 2006 Aug;44(8) doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000223475.70440.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wagner TH, Upadhyay A, Cowgill E, Stefos T, Moran E, Asch SM, Almenoff P. Risk Adjustment Tools for Learning Health Systems: A Comparison of DxCG and CMS-HCC V21. Health Serv Res. 2016 doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. Constructing a control group using multivariate matched sampling methods that incorporate the propensity score. The American Statistician. 1985 Feb;39(1):33–38. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wagner AK, Soumerai SB, Zhang F, Ross-Degnan D. Segmented regression analysis of interrupted time series studies in medication use research. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2002 Aug;27(4):299–309. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2710.2002.00430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Penfold RB, Zhang F. Use of interrupted time series analysis in evaluating health care quality improvements. Acad Pediatr. 2013 Nov-Dec;13(6 Suppl):S38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lopez Bernal J, Cummins S, Gasparrini A. Interrupted time series regression for the evaluation of public health interventions: a tutorial. Int J Epidemiol. 2016 doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw098. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Soumerai SB, Mah C, Zhang F, Adams A, Barton M, Fajtova V, et al. Effects of health maintenance organization coverage of self-monitoring devices on diabetes self-care and glycemic control. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(6):645–52. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.6.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.SAS (9.1.3) SAS Publishing Inc; North Carolina: [Google Scholar]

- 36.Whitlock EP, Orleans CT, Pender N, Allan J. Evaluating primary care behavioral counseling interventions: an evidence-based approach. Am J Prev Med. 2002 May;22(4):267–84. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00415-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stevens J, Truesdale KP, McClain JE, Cai J. The definition of weight maintenance. Int J Obes. 2006;30:391–99. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Butterworth S, Linden A, McClay W, Leo MC. Effect of motivational interviewing-based health coaching on employees' physical and mental health status. J Occup Health Psychol. 2006 Oct;11(4):358–65. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.11.4.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dunn C, Deroo L, Rivara FP. The use of brief interventions adapted from motivational interviewing across behavioral domains: a systematic review. Addiction. 2001 Dec;96(12):1725–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961217253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.VanBuskirk KA, Wetherell JL. Motivational interviewing with primary care populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Behav Med. 2014 Aug;37(4):768–80. doi: 10.1007/s10865-013-9527-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]