Abstract

Transcatheter aortic valves (TAVs) represent the latest advances in prosthetic heart valve technology. TAVs are truly transformational as they bring the benefit of heart valve replacement to patients that would otherwise not be operated on. Nevertheless, like any new device technology, the high expectations are dampened with growing concerns arising from frequent complications that develop in patients, indicating that the technology is far from being mature. Some of the most common complications that plague current TAV devices include malpositioning, crimp-induced leaflet damage, paravalvular leak, thrombosis, conduction abnormalities and prosthesis-patient mismatch. In this article, we provide an in-depth review of the current state-of-the-art pertaining the mechanics of TAVs while highlighting various studies guiding clinicians, regulatory agencies, and next-generation device designers.

Keywords: TAVR, Transcatheter aortic valve, stent, minimally invasive, thrombosis, paravalvular leak, valve-in-valve

INTRODUCTION

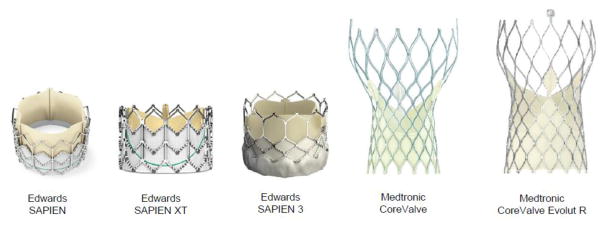

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) is an exciting new approach to treat aortic valve stenosis in patients who are classified as high-risk for open heart surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR). A transcatheter aortic valve (TAV) is designed to be compressed into a small diameter catheter, remotely placed within a patient’s diseased aortic valve under fluoroscopic guidance to take over the function of the native valve. Some TAVs (e.g., Edwards SAPIEN family) are balloon-expandable, while others (e.g. Medtronic’s CoreValve) are self-expandable owing to their shape-memory nitinol stents. In both cases, the TAVs are deployed within a calcified native valve that is forced permanently open and becomes the surface against which the stent is held in place by friction. More recently, TAVs have been used to replace failing bioprosthetic or transcatheter valves that were previously implanted in a procedure known as valve-in-valve (ViV). Figure 1 shows the TAVs that are currently FDA approved for clinical use in the United States.61 The design features, which most distinguish TAVs from their surgical counterparts -except for suture-less SAVRs- are the lack of a sewing cuff and the presence of a collapsible stent frame that houses the valve leaflets.

Fig. 1.

Transcatheter aortic valves FDA-approved for clinical use in the U.S. The figure is from Kheradvar et al (2015),1 with permission

Due to its minimally invasive approach, TAVR has a strong appeal to becoming the standard of care for low-risk patients. However, like any new device technology, the high expectations are dampened with growing concerns arising from frequent complications that develop in patients, indicating that the technology is far from being mature. Some of the most common complications that plague current TAVR devices include malpositioning, crimp-induced leaflet damage, paravalvular leak, thrombosis, conduction abnormalities and prosthesis-patient mismatch (PPM). These complications are currently difficult to predict prior to the procedure.; however, patient-specific risk factors are thought to include the calcification landscape of the native valve, geometric and mechanical properties of the aortic root, blood biochemistry and coagulability, and concomitant conditions such as hypertension, coronary artery disease, heart failure, etc. To ensure the robustness and safety of current and future TAVR devices, it is crucial to understand the relationship between potential complications, and their underlying mechanics. This work provides an in-depth review of the current state-of-the-art pertaining to TAVR mechanics and highlights various engineering studies guiding clinicians, regulatory agencies, and next-generation device designers. In what follows, we have divided the article into three main parts focusing on the fluid mechanics, solid mechanics, and future design concepts, respectively.

Fluid Mechanics of TAVR

Due to their particular design features, TAVs can undergo fluid and structural failure modes. The following sections provide a review of the major fluid mechanics-related failure modes, including paravalvular leak, PPM (particularly in valve-in-valve applications), thrombosis, and non-circular deployment.

Paravalvular Leak (PVL)

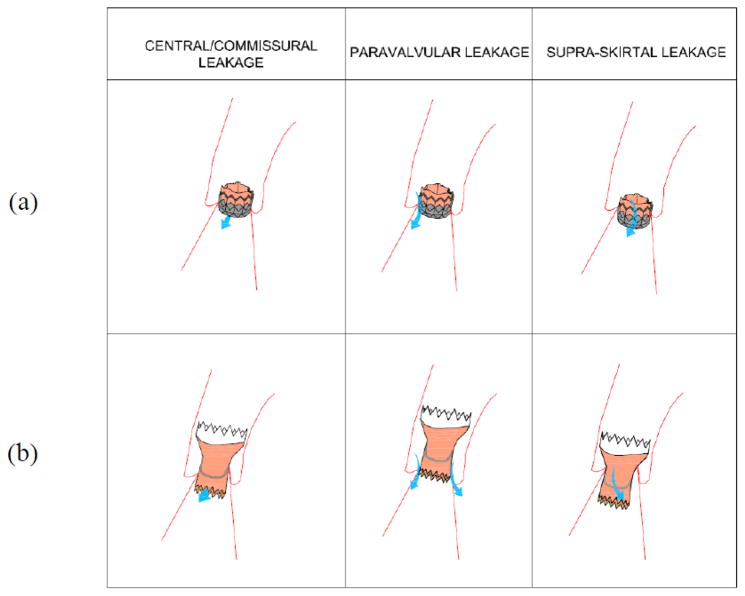

Valvular regurgitation is more prevalent after TAVR than SAVR 73, 89, 98, 109. In general, valvular leakage can be central or commissural (between the leaflets), paravalvular (between the prosthesis and deployment zone), or supra-skirtal (a form of PVL). Clinical studies have shown that even mild regurgitation can be associated with increased post-TAVR mortality 65, 133, 152. Figure 2 illustrates each mode of valvular leakage in the Edwards’s SAPIEN and the Medtronic’s CoreValve. Central or commissural regurgitation occurs in diseased, damaged, or improperly-deployed TAV when the leaflets do not fully coapt, while some prostheses have minor central leakage by design 73. If a THV is implanted too low within the annulus, supra-skirtal leakage can occur through the uncovered region of the stent. This has been observed in both SAPIEN and CoreValve, as only the lower part of their stents are shielded by a skirt 125. However, PVL is more frequent, affecting as many as 50% of patients with at least mild regurgitation 65, 73. Paravalvular leak can lead to congestive heart failure, hemolysis 105, 122, forceful contractions of the heart, and arrhythmias 50. Risk factors for PVL include heterogeneous calcification of the native annulus 24, 37, 73, 119, 144, malposition of the prosthesis 24, 96 and TAV undersizing 22, 24, 37, 39, 73. Figure 3 shows paravalvular leak at both coronary and non-coronary cusps in presence of different calcific lesions. Di Martino et al. suggested that self-expandable prosthesis may undergo resistance from the calcified native valve during deployment that may lead to a higher incidence of paravalvular leak 24. Accordingly, Abdel-Wahab et al. found that the occurrence of PVL was higher with CoreValve than SAPIEN 3, 51.

Fig. 2.

Types of valvular leakages in (a) Edwards SAPIEN valve and (b) CoreValve.

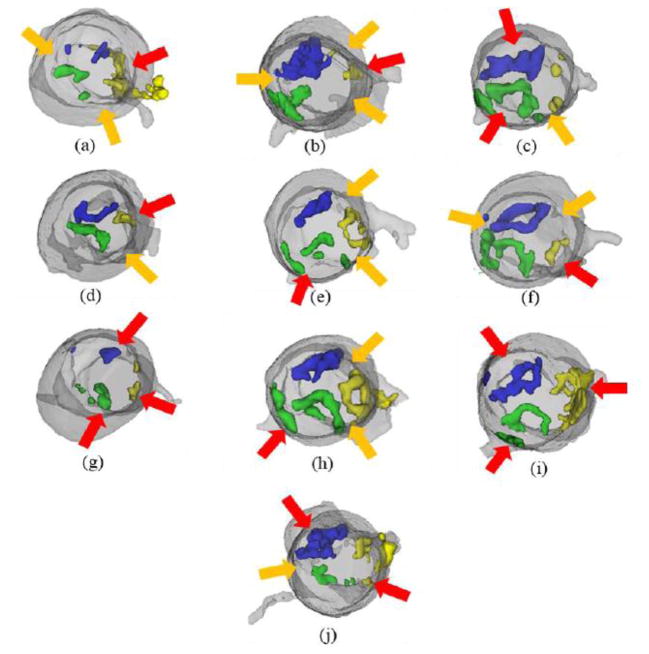

Fig. 3.

Segmented CT scans presenting reconstructed 3D models of the aortic root and calcific lesions overlaid with positions of paravalvular leak after TAVR based on respective transesophageal echocardiography scans. Red arrows correspond to PVL at cusp side and orange arrows correspond to PVL at commissure between two cusps. Green, blue and yellow denote the calcification in the right coronary, non-coronary and left coronary cusps respectively.

Anatomical and procedural factors have also been correlated with occurrence of PVL. A large aortic annulus as measured by CT may increase the chance of PVL 52, 101. Detaint et al. 22 defined a cover index representing the ratio of the difference between the TAV and annulus diameters. This index is a measure of TAV oversizing 47. A low cover index is associated with greater PVL.

The impact of PVL on patient mortality has motivated design changes to improve sealing 120. Design features, such as inflow skirts or cuffs as in Edwards’ SAPIEN 3, Boston Scientific’s Lotus, FoldaValve’s57 and St. Jude Medical’s Portico or alternative frame materials as used by Direct Flow are some examples that are being explored and utilized with some success 146.

TAVR Thrombosis

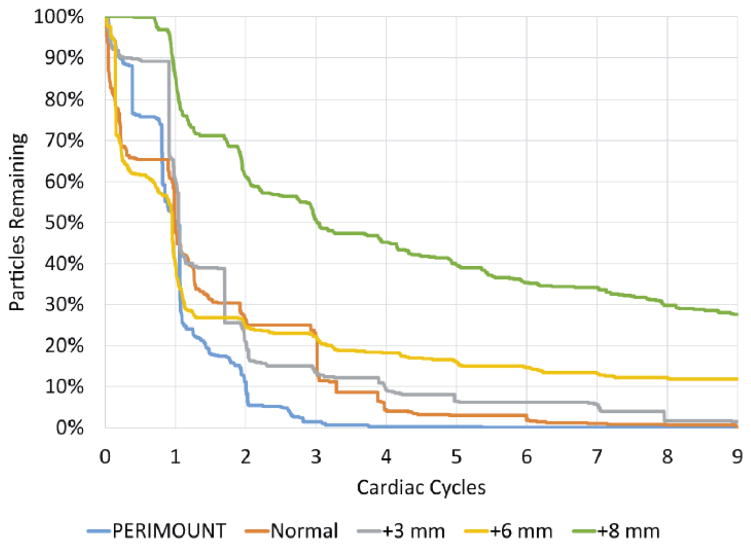

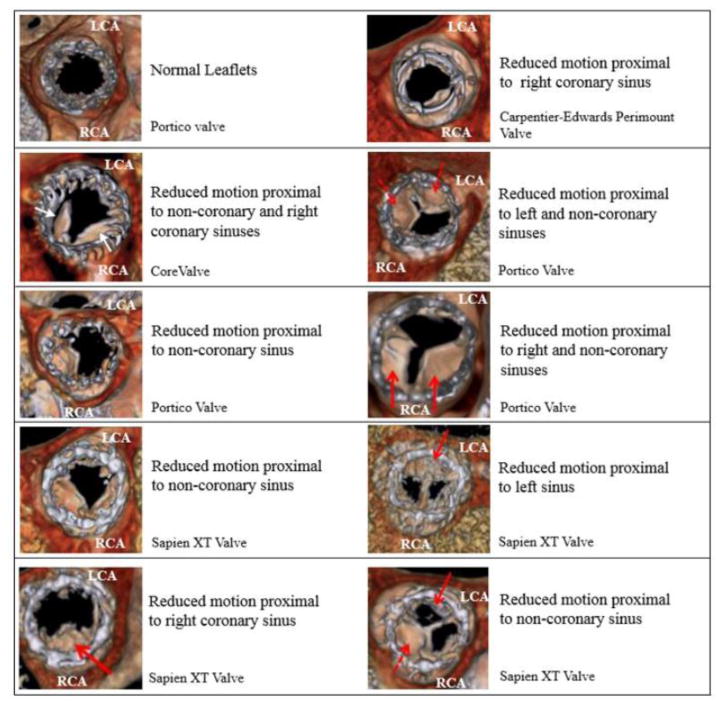

Thrombosis is the formation of blood clots or thrombi that can lead to partial or complete restriction of heart valve leaflet motion and/or embolization. Thrombosis in the cardiovascular system is traditionally discussed in terms of Virchow’s triad (fluid flow, foreign materials, and blood biochemistry). Presence of non-hemocompatible material in a blood circulation may lead to platelet activation 8. Sensitized platelets exposed to extended periods of flow stagnation and/or recirculation can result in thrombus formation 27, 59, 154. For example, stagnant flow in the sinus may expose these sensitized platelets to extended exposure time, making this site prone to thrombus formation 43, 115. Furthermore, it was shown that flow stagnation in the sinus was exacerbated with supra-annular implantation of the THV 42, 67, 86. Particle tracking results illustrated in Figure 4, show that there is a significant increase in the time taken for a given number of particles to exit the sinus at the highest supra-annular deployment 86, 88. These studies also demonstrate that the flow stagnation primarily occurs at the base of the sinus 42, 67, 86. After TAVR, the risk of thrombus formation rises in some patients 68. Factors that are thought to trigger post-TAVR thrombose formation are summarized as follows: small or under-expanded valves, premature stopping of antithrombotic or antiplatelet therapy, aggressive post-dilation, crimp-induced leaflet damage and geometric deformation of the valve stent 68, 93. Recently Makkar et al. 78 revealed evidence of reduced leaflet mobility to happen more frequently in transcatheter aortic valves compared to surgically-implanted bioprosthetic valve, which may explain consequent embolic stroke in patients undergoing TAVR. They also observed that warfarin improves leaflet mobility that supports their hypothesis indicating the reduced leaflet mobility is due to subclinical leaflet thrombosis. While the authors acknowledge the small sample size, p-values of 0.08 and 0.18 for PCI and CABG, respectively, may indicate that diminished coronary perfusion could be a factor in thrombus formation. In a correspondence to Makkar’s publication, Dasi et al. proposed a potential relationship between reduction in flow and formation of thrombus 48. Figure 5 shows some clinical images taken from Makkar et al. illustrating the reduced leaflet motion relative to the coronary ostia 48, 78. As can be seen in the figure, non-coronary sinuses as well as non-anatomical positioning of the TAV may explain possible flow stasis that correlates with the thrombus locations.

Fig. 4.

Time taken for a given number of particles to exit the sinus at the highest supra-annular deployment

Fig. 5.

Reduced motion leaflet identification images of different prosthetic and surgical valves presented in Makkar et al 2015 with respect to their corresponding sinuses. LCA denotes Left Coronary Artery and RCA Right Coronary Artery

Non-circular THV Deployment

As mentioned earlier, the interaction between the TAV and native aortic valve is not predictable. Sometimes, the stented-valve assumes an eccentric shape due to deployment in irregularly calcified native leaflets. For example, circular deployment is achieved only in 86% of the patients undergoing TAVR with a balloon-expandable prosthesis e.g., Edwards SAPIEN 21, 47.Likewise, a non-circular deployment in such cases is associated with further calcification and paravalvular regurgitation 21, 38, 155. Schultz et al. 112 reported that this problem is also prevalent in self-expandable valves such as the Medtronic’s CoreValve, where a majority of valves implanted in patients achieved a non-circular conformation. Abbasi et al. 2 investigated the synergistic impact of eccentric and incomplete stent deployment and showed that it may lead to higher localized stress regions over TAV leaflets in vitro. In addition, high mechanical stresses over TAV leaflets may induce enhanced tissue degeneration and reduce long-term valve durability 2, 4, 28, 130. On the contrary, some studies show that the relationship between non-circular deployment and paravalvular leak is not conclusive 71, 153. In a case-report, Jilaihawi et al. 53 noted that TAV under-expansion can lead to good hemodynamic function and excellent symptomatic recovery. Bench-top experiments conducted by Gunning et al. 43 using particle image velocimetry downstream of an eccentrically-deployed TAV suggested that the hemodynamic performance is invariable to the TAV configuration. They also noted that the eccentric TAV deployment may result in an asymmetric systolic jet with elevated turbulence and shear stress downstream of the valve; however, this phenomenon may not be significant enough to induce blood damage 43. While TAV oversizing can be used as a solution to compensate for eccentric TAV deployment, many studies have shown that oversizing contributes to annular injury or even rupture 71, 79. Oversizing by specific percentages optimizes risk/benefit ratio in terms of paravalvular leakage and conduction disorders 47, 69, 77. Sun et al 130 demonstrated that when the eccentricity value is above 0.5, the TAV may not properly close and is likely to result in increased commissural backflow leakage 112, 130.

Fluid Mechanics of Prosthesis-Patient Mismatch (PPM)

Rahimtoola et al. 19, 100 defined prosthesis-patient mismatch as an effective orifice area (EOA) smaller than that of a normal human valve. Successively Dumesnil and Pibarot explained that this definition can be applied to almost all valve replacements 28. Therefore, the heart must overcome the additional flow resistance via elevated pressures 10. Gorlin and Hakki 46 describe that transvalvular gradients depend on both EOA and transvalvular flow rate. While the cutoffs for PPM have been debated, PPM occurs when the prosthesis’ EOA normalized by body surface area is less than 0.85 cm2/m2 28.

Valve-in-Valve (ViV) implantation is a procedure in which a TAV is deployed within a failing bioprosthetic or transcatheter valve 83. Due to the typically high-risk or inoperable classification of these patients, ViV provides a viable valve replacement option when a second surgical procedure is not an option 32, 147, 150. With this procedure being the patient’s second valve replacement, there is always a high probability of coronary obstruction, PPM and residual stenosis 34, 145. Other in vitro studies have also suggested similar consequences such as the study by Azadani et al.12 conducted to test the hemodynamics of TAVs in degenerated -and particularly small-sized- bioprostheses. Careful selection of the TAV for ViV needs to be considered to mitigate the risk of paravalvular leakage as well as residual stenosis.12, 13 When Edwards’ SAPIEN and Medtornic’s CoreValve were implanted in surgical valves with internal diameters less than 20 mm, elevated post-procedural gradients (>20 mmHg) were found in 59% and 20% of patients, respectively 31, 138, 145. This is thought to be due to the intra-annular nature of the SAPIEN family of valves, whereas CoreValves are supra-annular by design 29. A recent in-vitro study by Simonato et al116 has emphasized the likelihood of having low pressure gradients associated with the supra-annular TAV implantation in particularly-small bioprostheses. The type of the bioprosthesis used also plays a role in the function and hemodynamic assessment of the ViV setup. The differences are elaborated in a study by Sedaghat et al.,113 as the paravalvular leakage was found higher when an Edwards’ SAPIEN was implanted within a 23mm Edwards’ Perimount compared to that seen when a Medtronic’s CoreValve was implanted in the same valve. Surprisingly, conflicting results were observed when the same TAVs were implanted within a St. Jude Medical’s Trifecta. The design of the Trifecta valve with leaflets sutured on the outside of the stent rather than on the inside may be a reason for this difference.

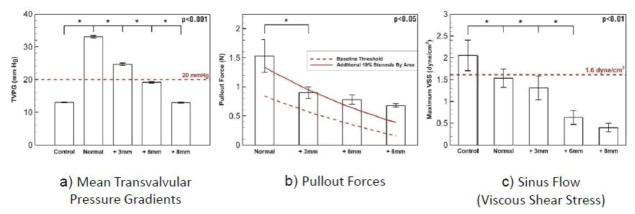

Other studies have shown that optimal size and placement of TAVs may exist outside the current guidelines 29, 86, 87. One possible solution to improve post-procedural gradients and minimize PPM is to implant the TAV in a supra-annular position (Figure 6a), effectively bypassing the geometric constraints imposed by the semi-rigid bioprostheses 86, 116, 158. However, several risks are associated with supra-annular deployment, including device migration or embolization (Figure 6b), coronary obstruction30, 127 as described by Dvir et al.30 tested in vitro by Stock et al.127, and thrombose formation due to flow stagnation within the sinus region (Figure 6c). An in vitro risk-benefit analysis of supra-annular deployment of a SAPIEN XT in a small surgical bioprosthetic valve demonstrated that the optimal deployment is in the range of 3 to 6 mm supra-annular. Another in vitro study by Groves et al. has shown that placement of a TAV within the annulus of a bioprosthetic valve with no more than 5 mm distance from its annulus should be ideal42. Any further displacement of the valve can be associated with detrimental effects on the observed hemodynamics. Groves et al. suggested that the transcatheter valve placement as close to the bioprosthetic valve annulus as possible provides optimal hemodynamics in the sinuses of Valsalva and ascending aorta42.

Fig. 6.

Risks associated with supra-annular deployment of a Transcatheter Aortic Heart Valve

Considering all the above-mentioned in vitro studies, we emphasize that clinicians must first consider patient-specific anatomic characteristics and carefully weigh the benefit of intra- or supra-annular valve implantation in reducing post-procedural gradients against the potential risk for valve thrombosis, conduction abnormality and device migration.

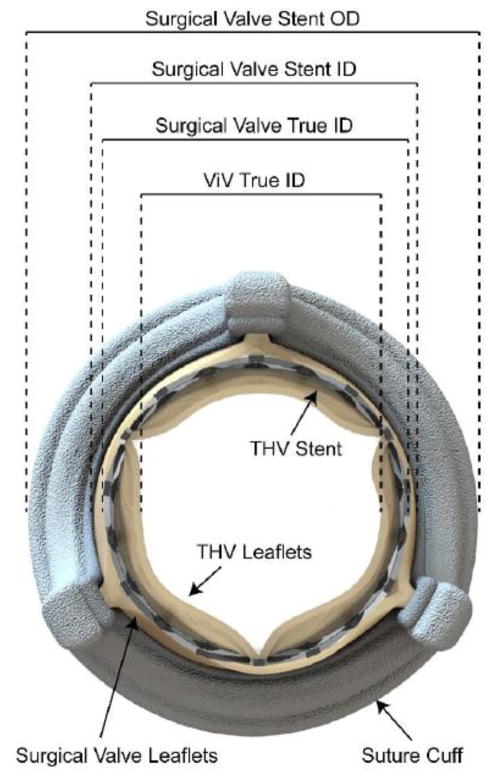

Figure 7 shows a schematic of a typical ViV arrangement in which a transcatheter valve is deployed within a stented surgical bioprosthetic valve. The relative dimensions described in the figure vary among valve types. For instance, a 23mm Edwards’ PERIMOUNT and a 23mm Medtronic Mosaic are indicated for an annulus approximately 23mm in diameter, however, the internal diameters are 21mm and 18.5mm, respectively. A 23mm Edwards’ SAPIEN XT could expand 2.5mm further within the PERIMOUNT rather than the Mosaic, thus leading to less PPM and lower gradients. As shown in the figure, most of the area is occupied by the original surgical valve. Bapat et al.16 helped creating a standardized ViV sizing and positioning guidelines by deploying various sizes of TAVs in a wide range of surgical bioprostheses. A summary based on that study is shown in Table 1 exhibiting different sizes of a stented surgical aortic valve and their corresponding valve-in-valve matches for the Edwards’ SAPIEN XT, Medtronic’s CoreValve, and St. Jude Medical’s Portico. With ViV sizing guidelines in place, knowing a patient’s surgical valve type and size allows for appropriate TAVs to be selected for the purpose of ViV.

Fig. 7.

Valve in Valve (ViV) arrangement using a stented valve as the surgical valve and a transcatheter aortic valve as the Valve-in-Valve

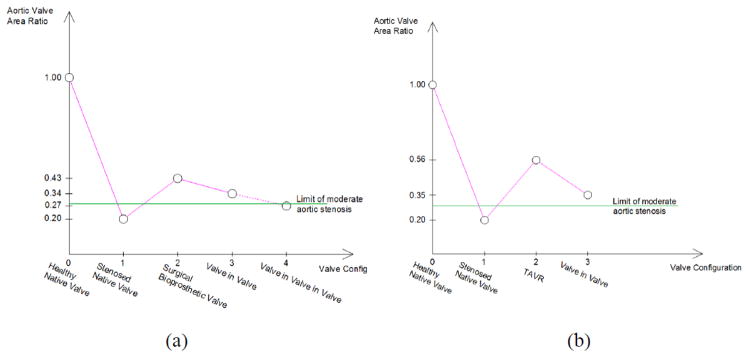

Figure 8 shows the evolution of the aortic valve area as the condition and configurations of a diseased aortic valve changes. The figure compares the improvement level in aortic valve area after the implantation of a TAV and a surgical bioprosthesis. The Figure considers 3.5 cm2 as the healthy aortic valve area and the ratio of 1.0 represents a healthy case. Gavina et al. show that TAVs may lead to lower gradients than surgical valves in native aortic valve replacement 36, 136. The Figure also shows the level of reduction in valve area after ViV 76, along with a comparison valve area in ViV configurations when the diseased bioprosthesis is a surgical valve versus a TAV 103. Due to the lack of published data regarding valve-in-valve-in-valve procedures, the value adopted in this figure is only a projection based on a fractional reduction seen in the ViV configuration results. In this case, a second ViV deployment may drop below the 1 cm2 cutoff for severe aortic stenosis 55, 97.

Fig. 8.

Evolution of the aortic valve area as the configuration of the valves change in the case of (a) a surgical heart valve implantation originally and (b) a transcatheter aortic heart valve implantation originally. The value of 1.00 corresponds to a healthy aortic valve area and is taken to be 3.5 cm2.

Structural Mechanics of TAVR

Many catastrophic TAV failures observed in clinics can be explained from a biomechanics perspective. For instance, excessive radial expansion force exerted by the TAV stent may lead to aortic annulus injury, while insufficient force may result in PVL and device migration. In addition, improper TAV positioning can cause coronary ostia’s occlusion. Thus, a quantitative understanding of the biomechanical interactions between the native aortic tissue and TAV is essential for scientifically-justified design of the next-generation devices and an enabling step towards patient-specific device selection and procedural planning. More recently, several studies on structural analyses were performed using finite element models to understand the interaction between TAV and aortic root interaction. These studies are mainly classified into two groups: (1) simulation of biomechanical interactions between the TAV devices and the aortic root, and (2) post-TAVR evaluation of the device performance. The accuracy of these models largely depends on three critical factors: geometry, material properties, and boundary conditions. The processes to determine these factors are reviewed in the subsequent section.

Modeling the interactions between TAV and aortic root

A deployed TAV device comes into contact with the aortic root, leaflets and left ventricle besides any potential calcification spots. Thus modelling these anatomical structures are critical to develop accurate computational models for TAVR. The aortic root, including the aortic sinuses and the ascending aorta, as well as the calcification can be segmented directly using commercial image-processing software such as Avizo (VSG, Burlington, MA) and Mimics (Materialise Inc., Belgium) by selecting an appropriate window width of Hounsfield units (HU) 18, 142. For example, Wang et al. 142 chose a window width of 950 and -50 HU for the segmentation of the aortic root. However, the valve leaflets typically cannot be directly segmented from the images using the software, and have been ignored in many studies 11, 44. The segmentation of the native leaflets requires manual digitization and reconstruction process, 121, 141–143 which can be cumbersome and prone to error.

The aortic root and native leaflets are often modeled using shell elements 18, 44, 90, 108, 121. However, transverse shear stiffness may not be accurate in shell elements, and thus may give inaccurate results when modeling out-of-plane bending responses. Furthermore, the addition of calcification to the aortic root and leaflets requires precise accounting of volume and geometry, for which a 3D element is required. Calcification may result in highly complex geometries and can be embedded into the leaflets and sinuses, which was not included in many of the earlier computational models 11, 15, 18, 44, 90. Recent studies indicate that it is advantageous to model both aortic root and calcification using brick elements 17, 41, 141–143. Only a few studies include the left ventricle (LV) in modeling TAVR 108, 141–143; however, Wang et al. 141 reported that by including some portion of the LV, the tissue-TAV interaction force increases upon stent deployment; thus inclusion of the LV may improve the accuracy of the analysis.

Various material models have been used to describe aortic tissue behavior, including rigid walls 107, linear elastic models 15, 41, 107, isotropic hyperelastic models 17, 18, 44, 56, 90, 107, and anisotropic hyperelastic models 11, 90, 141–143. A more advanced material model can capture the tissue response more accurately, providing more accurate simulation results at the expense of computational time.

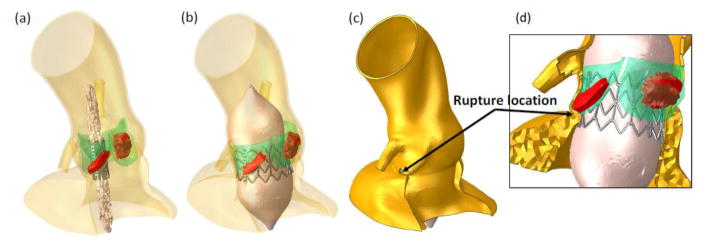

Patient-specific computational models for TAVR can potentially be utilized as a tool to refine patient selection, evaluate device performance, and eventually improve clinical outcomes for each patient. Many FE models 11, 15, 17, 18, 41, 44, 90, 107, 141–143 have been developed over the past several years to analyze the biomechanics involved with TAVR in specific patient groups. These models have been used to evaluate the potential for coronary artery occlusion 18,141–143 and migration 17, as well as the feasibility of complex clinical cases such as ViV 18. Notably, Wang et al. 142 have described a complex patient-specific TAVR model that includes realistic aged human tissue properties including the aortic root failure criteria defined by experiments 81, as well as a fluid cavity modeling approach to simulate the balloon expansion of the Edwards’ SAPIEN stent (Figure 9). They simulated TAVR in three patients considered to be at a higher risk of aortic root rupture, and showed that asymmetric calcium deposition within the root may be a cause of TAVR-induced aortic rupture clinically observed. Collectively these studies have shown that the size and location of calcium deposits are critical to the success of TAVR procedure 108, 141–143. Calcification can prevent full or symmetric stent expansion leading to paravalvular leakage 17, 90, 141–143 and distortion of the TAV leaflet configuration 11, 44, 90.

Fig. 9.

(a) Pre- and (b) post-deployment geometries of the aortic root of Case 1. (c) full and (d) local views of the deformed the aortic root and balloon deployment indicates annulus tearing under the left coronary ostium due to dislodgement of calcification into the vulnerable part of the aortic sinus. Adopted from Wang et al. Biomech Model Mechanobiol (2015) 14:29–38

Modeling of post-operative device performance

Li and Sun 75 presented the first FE model for TAV leaflet deformations. The leaflet material behavior was defined by the nonlinear, anisotropic, hyper-elastic Fung-type model fitted to planar biaxial testing data of thin glutaraldehyde-treated bovine pericardium and porcine pericardium. Li and Sun 75 showed that leaflet stresses decrease with increasing tissue thickness, and under the same loading and boundary conditions, bovine pericardium leaflets have a lower peak stress compared to porcine pericardium leaflets (59%). All the cases of the TAV leaflet stresses and strains 75 were significantly higher compared to those reported by Sun et al. 131 for traditional surgical bioprosthetic valve leaflets. These results suggest that TAVs will have a limited long-term durability compared to surgical bioprosthetic valves, particularly the TAVs utilizing porcine pericardium leaflets.

In a follow-up study using this same FE model 75, Sun et al. 129 showed that the elliptical deployment compromises TAV leaflet coaptation and increases leaflet stresses. A stent elliptical eccentricity of 0.68 resulted in a 143% increase in the leaflet peak stress compared to the nominal circular configuration. Furthermore, it was shown that an eccentricity exceeding 0.5 can lead to central aortic regurgitation. Incomplete stent expansion has also been shown to distort the configuration of the leaflets 123, 157. Abbasi and Azadani 1 studied the impact of incomplete stent expansion on the TAV leaflet deformation in a 23 mm valve using FE model. They found that reduction of the stent diameter by 2–3 mm induces sharp bends in the leaflets during closure, which acted to increase the leaflet peak stress by 40.1–78.2% compared to the nominal valve under identical loading. Further reduction of the stent diameter by 4–5 mm increases the leaflet peak stresses by 124.1–158.6%. In the real scenario, the leaflet peak stresses during systole in the under-expanded configuration would also likely be higher than reported here 1, because incomplete expansion can lead to increased transvalvular pressure gradients 14, 45, 54, 64, 66, 70, 91, 148. Consequently, both short- and long-term functions may be compromised in an elliptically or under expanded deployed TAV.

Martin and Sun 82 recently investigated TAV leaflet durability through FE analysis by implementing a computational soft tissue fatigue damage model, which includes descriptions of the stress-softening and permanent set effects of glutaraldehyde-treated bovine pericardium subjected to cyclic loading 114, 132. The effects of cyclic loading on TAV and surgical bioprosthetic valve leaflets were compared. In both valves, cyclic loading induced changes in the leaflet tissue properties and geometries, and altered the leaflet stress and strain patterns, which could not be predicted in traditional FE models utilizing instantaneous tissues properties. Under identical loading conditions, the TAV leaflets sustained higher stresses and strains as observed by Li and Sun 75, which resulted in increased fatigue damage compared to the surgical valve leaflets. The simulation results suggest that the THV durability may be significantly reduced compared to surgical valves from 20 years to about 7.8 years post-implantation. This model may be useful in optimizing TAV design parameters to improve leaflet durability, and assessing the effects of under expanded, elliptical, or non-uniformly expanded stent deployment on THV durability.

Future TAVR Designs

The TAVR introduction has transformed the traditional surgical approach to heart valve disease by offering significantly minimal procedures particularly for high-risk patients who have been considered unsuitable for open-heart surgeries either in its traditional form or minimally-invasive.61, 65 Major TAVR advantages to the traditional surgical approaches can be summarized as refraining cardiopulmonary bypass, aortic cross-clamping and sternotomy that significantly reduces patients’ morbidity.49 However, current guidelines do not yet recommend TAVR for patients with intermediate or lower risk for open heart surgery. These risks are usually quantified based on the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) score23 or the EuroSCORE (European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation).94, 104

Society of Thoracic Surgeons established a measure - STS AVR composite score- that includes two outcomes domains, risk-adjusted mortality and risk-adjusted morbidity related to aortic valve replacement complications (i.e., reoperation, stroke, kidney failure, infection of the chest wound, or prolonged need to be supported by a breathing machine, or ventilator)23. In a similar fashion, EuroSCORE is a risk model that calculates the risk of death after a cardiac procedure. The model works based on 17 items of information about the patient, the cardiac condition and the proposed procedure to be performed,94 and uses logistic regression to calculate the mortality risk.104 High, intermediate and lower risks are usually quantified based on these scores.

Current guidelines do not recommend TAVR in patients at intermediate or low surgical risk since several issues affecting outcomes remain unresolved, including durability, subclinical thrombosis,80 vascular complications, neurological events, rhythm disturbances, and paravalvular leakage. Reducing the incidence of major adverse events associated with TAVR is crucial, as these risks are not acceptable to a standard-risk surgical population. However, innovations in devices and technologies for delivery system are rapid and unceasing, leading to the treatment of younger population in a near future. Additionally, PARTNER II trial showed that in intermediate-risk patients, second generation Edwards’ SAPIEN system is comparable to SAVR with respect to the primary end point of death or disabling stroke.72 In parallel, there are several ongoing trials of novel transcatheter aortic valves, which aim to solve many of the issues that currently are major challenges to heart valve developers.84, 137, 151

The current limitations of TAVR that prevents its use in lower risks patients are summarized below:

Vascular complications from large delivery systems, which necessitates smaller profiles.

Paravalvular leak, which necessitates better sealing strategies74,58, 134.

Device malpositioning, which necessitates repositionable and/or retrievable devices 139. This is particularly important when TAVR procedures are performed by interventional cardiologists with less TAVR experience.

Permanent pacemaker, which necessitates a better understanding of the mechanical loads imposed by TAVR devices on the cardiac conduction system. Most investigators agree that conduction abnormalities are primarily due to mechanical compression of the cardiac conduction system by the device, although other factors may be involved 95, 126, 140.

Device failure, which necessitates a better understanding of the mechanical and biological durability of TAVR devices. Durability concerns may arise from sub-optimal deployment, leaflet calcification, and thrombus formation to mention a few. More recently, quantitative data has become available assessing transcatheter heart valves’ leaflets durability. 33 The report estimates that TAV degeneration was about 50% within 8 years post-TAVR with early-generation balloon-expandable TAV devices.

TAVR involves delivery, deployment, and implantation of a crimped, stented valve within a diseased aortic valve or degenerated bioprosthesis. A major limitation of these procedures is the diameter to which the stent can be crimped without damaging the leaflet tissues within. Currently, only a handful of FDA-approved transcatheter valves (Figure 1) are being used in elderly aortic stenosis patients.61 Recently, PARTNER II trial showed that in intermediate-risk patients, second generation Edwards’ SAPIEN system is comparable to SAVR with respect to the primary end point of death or disabling stroke.72 TAV durability has not yet tested in any of the trials. However, a recent report from St. Paul’s Hospital in Vancouver, Canada suggests post-TAVR’ long-term durability with early-generation balloon-expandable valves is a concern with significant increase in degeneration rate 5 to 7 years post-TAVR. The report estimates TAV degeneration to be about 50% within 8 years. 33

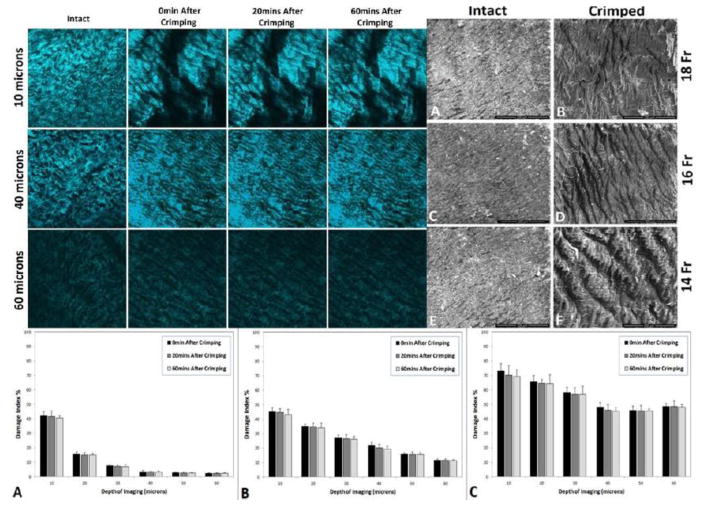

Avoid stent-crimp-induced leaflet injury

More recently, quantitative data has become available assessing the crimping-related damage to transcatheter heart valves’ leaflets. Most of these studies that rely on the histology of pericardial leaflets 20, 63, 156 have credibly documented that mechanical stresses applied to pericardial leaflets result in disruption of their collagen fibers’ natural patterns, and may lead to calcification and early valve problem.62, 111, 156 The results of a more recent study published in the New England Journal of Medicine by Makkar et al. indicate that transcatheter aortic valves may lead to subclinical leaflet thrombosis based on the results from PORTICO IDE trial in comparison to SAVORY and RESOLVE registries.78 A potential mechanism could be the injured rough surface of the leaflet facilitating thrombus formation. Whether the stent-crimp damage to the leaflets is transient or permanent is a critical question that Alavi et al. have recently addressed.4 in their study. They tested the effect of stent crimping on collagen fibers of the bovine pericardial leaflets at the surface and in deeper layers under scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and second harmonic generation (SHG) microscopy.4 Uncrimped leaflet tissue samples were imaged, followed by imaging tissue segments after crimping in a stented valve, immediately following, at 20 minutes, and at 60 minutes after crimping. The crimping experiments were performed for multiple crimped sizes (i.e., 14, 16, and 18 French) The results are shown in Figure 10, indicating significant tissue damage occurring both at the surface of the pericardial tissue and through its depth. Moreover, the collagen fiber alteration induced by crimping is irreversible and does not return to its original arrangement over time.

Fig. 10.

(Left) SHG microscopy images compare the structural changes of intact and crimped pericardial tissues at depths of 10, 40, and 60 microns for crimping sizes of 18Fr over time. (Right) SEM images show intact (A, C, and E) and crimped (B, D, and F) states of three different pericardial leaflets at 18Fr, 16Fr, and 14Fr, respectively. Comparison of SEM images demonstrates substantial changes on the surface microstructure due to crimping, which increased with reduction of the collapsed profile. The images are adapted with permission from Alavi et al Annals of Thoracic Surgery (2014).4

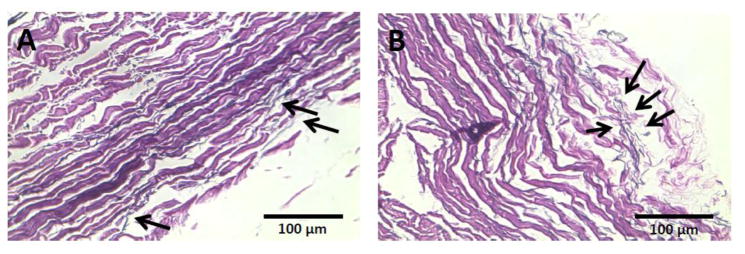

In another study, Sinha and Kheradvar showed significant levels of elastin fragmentation in stent-crimped leaflets when compared to intact pericardial leaflets as shown in Figure 11.117, 118 In that study, Glutaraldehyde-fixed bovine pericardial leaflets (Neovasc, Richmond, BC, Canada) were sewn into a self-expandable Nitinol stent to make transcatheter valve. The valves were divided into two groups of crimped and uncrimped, and each group was split into two to be exposed either to a calcifying solution 40 or to control solution (normal phosphate buffered saline). For the crimped group, the valves were carefully crimped with a standard crimper at 18Fr and 14Fr and held crimped for 20 minutes. All the leaflets were then equally cut into 0.5″X0.5″ segments and placed in 50 ml of either control, or calcifying solution similar to what described by Grases et al. 40 All groups were maintained at pH 7.5, 37°C, on an orbital shaker at 400 rpm for 7 weeks. The samples were thoroughly rinsed with saline before embedding for histological analysis. Each tissue sample was individually embedded, sectioned and stained for elastin stain (Verhoff’s Van Geison). Figure 11A demonstrates that the elastin fibers remain intact while the elastin fibers in crimped leaflet have been damaged in the depth of leaflet. The images show that elastin fibers in uncrimped leaflets have intact thin fibers morphology as pointed by black arrows in Figure 11A in comparison to fragmented thin elastin fibers in crimped leaflet in Figure 11B.

Fig. 11.

Verhoeff Van Gieson (VVG) staining of two cross sections extracted from Uncrimped (A) and crimped (B) bovine pericardial leaflets, respectively. Image A demonstrates intact elastin fibers (long black thin lines) in a cross section of an intact pericardial leaflet and image B shows fragmented elastin (short black thin lines) fibers in a stent-crimped leaflet. Elastin fibers in both cross sections were pointed by black arrows. Bars are 100 μm. The images are adapted from Sinha and Kheradvar (2015) 118

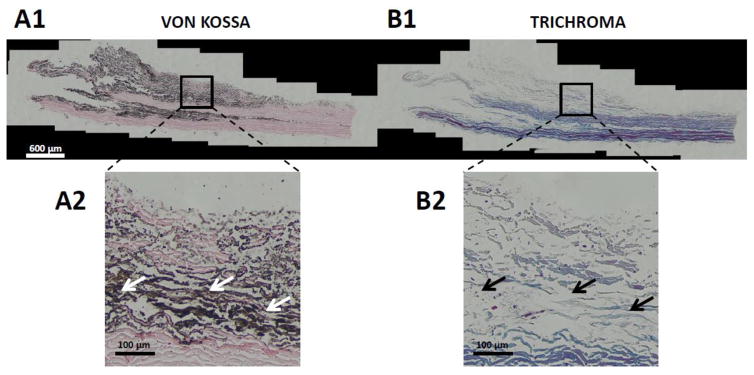

Transcatheter Heart Valve Calcification

Overall, stent-crimping damages in the depth of leaflets may increase calcification. While not yet systematically studied, microscopic damage to the leaflet collagen fibers is observed to be associated with calcification. In a recent in vitro calcification study, Kheradvar group at UC Irvine found that at the locations of significant damage to the collagen fibers within the leaflets, heavy calcification is present. The leaflet samples were studied after 50 million cycle accelerated wear test in presence of calcium-phosphate buffer at 37°C. Figures 12A1 and 12B1 compare similar cross-section of a stent-crimped pericardial leaflet stained for calcium-phosphate (von Kóssa stain) and collagen fibers (Trichrome stain). Two local zones shown in Figures 12A2 and 12B2 have been magnified and compared to reveal the association between the calcium deposition and collagen fiber damage in the stent-crimped leaflet. The higher calcium deposition (black color fibrils pointed by white arrows in Figure 12A2) has been observed wherever collagen fibers are damaged indicated by faded blue fibrils pointed by black arrows in Figure 12B2. This phenomenon is not noticed in the areas where collagen fibers are still undamaged as shown in Figure 12. More studies are underway to find out whether stent-crimping damage has causal relationship to leaflet calcification.

Fig. 12.

Von Kossa and Trichrome staining of a cross section extracted from a crimped bovine pericardial leaflet. Both cross sections were extracted from the same location in the leaflet and then were stained for calcification and ECM investigations. A1 and B1 are mosaic images ( 10 stitched images) of Van Kossa and Trichrome staining of the cross section, respectively. A2 and B2 are two magnified local images to compare the calcification versus ECM. Image A2 and B2 show hydroxyapatite deposition and collagen fibers in the same location of tissue. Black and white arrows represent the calcified and damaged ECM zones in the leaflet. Bars are 600 μm and 100 μm in mosaic and magnified images, respectively. The images are from Kheradvar

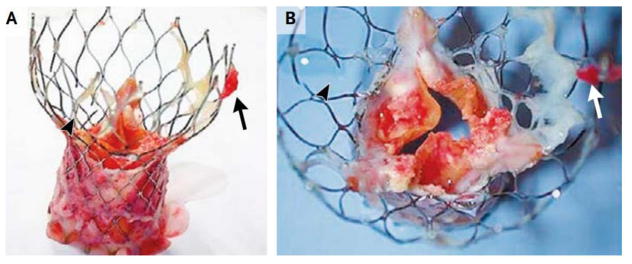

Transcatheter heart valves are prone to all the failure modes of surgical bioprosthetic heart valves.92 In addition to those, specific features to these prostheses may contribute to their failure. Recent studies describe adverse events due to late-stage embolization, subclinical thrombosis and heart valve compression.78, 92 Other investigators reported the failure of Edwards’ SAPIEN and Medtronic’s CoreValve due to severe leaflet calcification and cusp rupture.92, 99 Structural valve failure is attributed primarily to severe leaflet calcification, causing cusp rupture and obstructive leaflet function.99 The exact mechanisms that facilitate such rapid matrix degeneration are currently unknown; however, predominant reasons may include repeated chronic mechanical stresses on valvular leaflets causing initiation and accumulation of calcium deposition.135 In a recent editorial correspondence in the New England Journal of Medicine published in March 2015, two patients with severe calcification of 29mm CoreValve prostheses were presented and discussed only after five years post-implantation. Explant of the prosthesis revealed severe leaflet calcification, degeneration, and thrombus formation as shown in Figure 13.102

Fig. 13.

Panel A shows the presence of fresh thrombus (arrow), and panel B indicates the severe calcification and rupture of leaflets in a CoreValve. The images are taken from Richardt et al., NEJM, 2015 with permission.

The recent clinical reports on calcification of transcatheter aortic valves may be only the tip of the iceberg, and now that a few years have passed since the first generation of implants, more clinical cases of crimp-induced problems may be found. Considering the substantial numbers of TAVR in the recent years, the first comprehensive 10-year follow-up data can be expected by 2020.9 Overall, the field of heart valve engineering currently lacks knowledge about the in vivo mechanistic processes involved in transcatheter valvular dysfunction and calcification due to crimping damage.

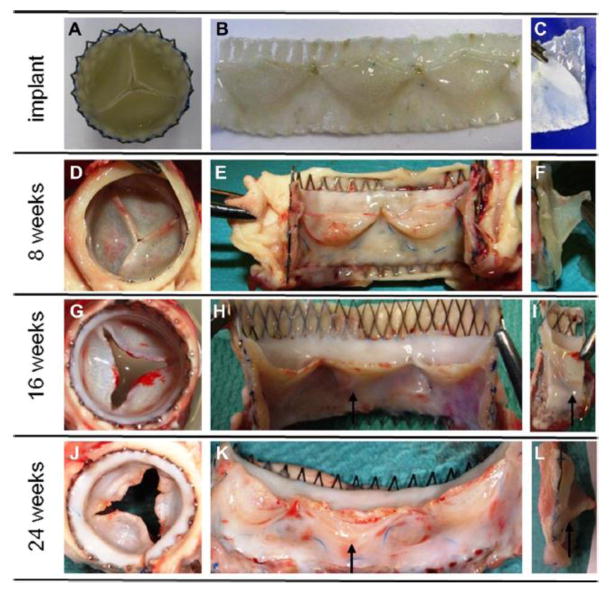

Transcatheter Tissue Engineered Heart Valves

Transcatheter tissue engineered heart valve (TTEHV) technology is a recent advancement that combines minimally invasive strategies with living tissue engineered heart valves aiming to overcome the limitations of current TAVR technologies by providing growth, remodeling, and regeneration capabilities. There have been promising reports recently demonstrating a potential role for this technology in near future. These reports have taken advantage of the use of either classical in vitro tissue engineering approaches 25, 85, 110 or the newly introduced in situ and “off-the-shelf” procedures.26, 149 In conventional approaches, the tissue engineered valves are developed in vitro by seeding cells in a proper scaffold to generate living tissue, whereas the in situ approaches take into account the intrinsic regenerative capacity of the body to repopulate the substrate 60. The latter provides an off-the-shelf feature that may extremely simplify the commercialization process and greatly enhance the clinical relevance of these valves. To the best of our knowledge, the introduction of TTEHV dates back to 2005 in the work of Ruiz et al.106 where they reported data on percutaneous implantation of decellularized valves made of biodegradable small intestinal submucosa (SIS) in a swine model. Even though the valves had progressive thickening after one-year implantation, the histologic remodeling and formation of new extracellular matrix (ECM) were promising. One year later, Stock et al.128 showed that the use of a thin SIS wall inside a stent would protect the delicate decellularized valves from crimping damages. This suggested the use of tissue engineered valves that included their own vascular wall. Schmidt et al110 employed this concept and demonstrated the feasibility of TTEHV technology by using stem cells for fabrication of heart valves. Those valves were implanted transapically in sheep at pulmonary valve position and exhibited acceptable in vivo functionality for up to 8 weeks with better extracellular matrix formation but with thickened leaflets. At that time, it was speculated that the thickening effect is due to the crimping procedure, however, later on Dijkman et al.25 showed that the thickening is due to functional in vivo remodeling procedures rather than crimping effects. Another promising and pioneering study was the work of Emmert et al.35 where, in contrast to the other works, they tested bone-marrow based TTEHVs at aortic position instead of pulmonary position. The valves successfully withstood the high pressure environment in the systemic circulation for the two-week period of this study. Recently, in two different works Weber et al.149 and Driessen-Mol et al.26 studied the use off-the-shelf TTEHV approach in short term (up to 8 weeks) and long term (6 months), respectively. Both studies showed substantial ECM formation whereas the long-term study revealed significant recellularization and elastin fiber formation. Nevertheless, progressive regurgitation was observed as reported in Figure 14, which was mentioned to be due to the suboptimal valve design26. New studies are currently underway to address these issues 5–7, 124. It is noticeable in all these studies that no matter what approach is used in fabrication of TTEHV, this technology can eliminate the damages caused by TAVR stent-crimping mainly due to the self-repair capacity of the valves, which leads to healing and rapid ECM production post-implantation.25, 110 Although the outcomes of these studies are promising, further studies are required to provide information on long term functionality and clinical safety and durability of these valves.

Fig. 14.

Macroscopic images of a TTEHV prior and after implantation in sheep pulmonary position. The valves were fabricated using biodegradable scaffolds and in vitro culture of vascular derived cells. The valves were decellularized prior to implantation to provide an off-the-shelf characteristic. The images were adapted from Driessen-Mol et al., 2014.

Summary

Despite the revolutionary aspect of transcatheter aortic heart valves in offering high-risk patients an alternative to open heart surgery, adverse effects are still to a large extent of unresolved causes and consequences. The potential failure modes and durability concerns associated with TAVs fall under fluid mechanics, structural mechanics and microscopic mechanics. More studies in-vivo and in-vitro are deemed necessary to better understand and connect the causes to the effects and therefore to better contribute to more efficient and convenient TAV designs. To date, the main problems associated with TAVR revolve around paravalvular leakage, thrombosis, non-circular transcatheter heart valve deployment, conduction abnormalities, crimp-induced leaflet damage and patient-prosthesis mismatch. Paravalvular leakage can lead to congestive heart failure, arrhythmias, forceful contractions of the heart, and high degree of mortality. Valve positioning, types of TAVs (self-expanding versus balloon expanding), locations and size of calcium nodules and the increased stresses on the leaflets due to eccentric deployment have the biggest impact on determining the regurgitation possibility and level. A quantitative understanding of the biomechanical interaction between the native aortic tissue and the TAV is essential for better design and selection of the appropriate valve. Leaflet thrombosis is another major problem associated with TAVR. Stagnation of flow in the sinuses and crimp-induced damage are potential reasons behind leaflet thrombus formation. Positioning of the TAV, under-expansion, aggressive post dilation and the injured rough surface of the leaflets due to possible crimping may be the underlying factors on thrombus formation. Non-circular heart valve deployment is a direct consequence of the complication that arises when the TAV and the native valve interact. The non-circular shape is assumed due to the highly calcified native leaflets. This leads to high stress regions over the TAV leaflets under dynamic loading that may lead to calcification and early valve degeneration. Optimizing the TAV design parameters to improve leaflet durability taking into account the effects of stent-crimping, under-expansion and non-uniform expansion is necessary. Patient-prosthesis mismatch is also one of the most impactful adverse effects of TAVR especially in the valve-in-valve configuration. PPM induces additional flow resistance, which can only be overcome with higher pressures. The types and positioning of TAVs along with the types of the bioprostheses dictate the efficiency and functionality of the ViV configuration. Despite the numerous studies, patient-specific anatomic characteristics are necessary for an optimum ViV setup. Valve-in-Valve-in-Valve procedures constitute another dimension of the ViV setup but more studies are still required for better understanding and assessment of the procedure. Overall, all the previous studies reported her have contributed to a significant understanding regarding TAVR procedures and have a big impact on implementing remedies in future TAV designs. Some of these remedies include implementing an inflow skirt, making a change in the frame material, avoiding stent crimping as it leads to the disruption of the fibers natural pattern and therefore calcification, and developing transcatheter tissue engineered valves that can withstand high pressure environment.

Procedures pertaining transcatheter aortic valve replacement are undergoing fast improvements. Despite the efforts and the diversity of the studies, more investigations are still required to acquire a comprehensive understanding and thus to implement this understanding into future design and developments and clinical applications to improve patients’ quality of life and valve durability.

Table 1.

Corresponding Valve-in-Valve matches for different sizes of Stented Bioprosthetic Surgical Aortic Valves

| Bioprosthetic Stented Valve True ID (mm) | Appropriate TAV Type for ViV | Corresponding TAV Annulus Size (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| 16 – 17.5 | Sapien 20 | 16 – 18 |

| 18 – 18.5 | Sapien 20 | 16 – 18 |

| CoreValve 23 | 18 – 20 | |

| Portico 23 | 19 – 21 | |

| 19 | Sapien 23 | 18 – 22 |

| CoreValve 23 | 18 – 20 | |

| Portico 23 | 19 – 21 | |

| 20.5–21 | Sapien 23 | 18 – 22 |

| CoreValve 23 | 18 – 20 | |

| Portico 23 | 19 – 21 | |

| 22 | Sapien 26 | 22 – 25 |

| CoreValve 26 | 20 – 23 | |

| Portico 25 | 21 – 23 | |

| 23 | Sapien 26 | 22 – 25 |

| CoreValve 26 | 20 – 23 | |

| Portico 25 | 21 – 23 | |

| 24 | Sapien 26 | 22 – 25 |

| CoreValve 26 | 20 – 23 | |

| Portico 27 | 23 – 25 | |

| 25–26 | Sapien 29 | 25 – 27.7 |

| CoreValve 29 | 23 – 27 | |

| Portico 27 | 23 – 25 | |

| 27 | Sapien 29 | 25 – 27.7 |

| CoreValve 29 | 23 – 27 | |

| Portico 29 | 25 – 27 |

References

- 1.Abbasi M, Azadani AN. Leaflet Stress and Strain Distributions Following Incomplete Transcatheter Aortic Valve Expansion. J Biomech. 2015;48:3672–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2015.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abbasi M, Azadani AN. The Synergistic Impact of Eccentric and Incomplete Stent Deployment on Transcatheter Aortic Valve Leaflet Stress Distribution. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2015;66:B253–B54. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abdel-Wahab M, Comberg T, Buttner HJ, El-Mawardy M, Chatani K, Gick M, Geist V, Richardt G, Neumann FJ, Segeberg-Krozingen Tavi Registry. Aortic Regurgitation after Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation with Balloon- and Self-Expandable Prostheses a Pooled Analysis from a 2-Center Experience. Jacc-Cardiovascular Interventions. 2014;7:284–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2013.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alavi S Hamed, Groves Elliott M, Kheradvar Arash. The Effects of Transcatheter Valve Crimping on Pericardial Leaflets. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;97:1260–66. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alavi S Hamed, Kheradvar Arash. A Hybrid Tissue-Engineered Heart Valve. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2015;99:2183–87. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.02.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alavi SH, Kheradvar A. Metal Mesh Scaffold for Tissue Engineering of Membranes. Tissue Engineering Part C Methods. 2012;18:293–301. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2011.0531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alavi SH, Liu WF, Kheradvar A. Inflammatory Response Assessment of a Hybrid Tissue-Engineered Heart Valve Leaflet. Ann Biomed Eng. 2013;41:316–26. doi: 10.1007/s10439-012-0664-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson JM, Rodriguez A, Chang DT. Foreign Body Reaction to Biomaterials. Seminars in Immunology. 2008;20:86–100. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arsalan Mani, Walther Thomas. Durability of Prostheses for Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2016;13:360–67. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2016.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Astudillo LM, Santana O, Urbandt PA, Benjo AM, Elkayam LU, Nascimento FO, Lamas GA, Lamelas J. Clinical Predictors of Prosthesis-Patient Mismatch after Aortic Valve Replacement for Aortic Stenosis. Clinics. 2012;67:55–60. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2012(01)09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Auricchio F, Conti M, Morganti S, Reali A. Simulation of Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation: A Patient-Specific Finite Element Approach. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Engin. 2013 doi: 10.1080/10255842.2012.746676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Azadani AN, Jaussaud N, Matthews PB, Ge L, Chuter TAM, Tseng EE. Transcatheter Aortic Valves Inadequately Relieve Stenosis in Small Degenerated Bioprostheses. Interactive Cardiovascular and Thoracic Surgery. 2010;11:70–77. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2009.225144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Azadani Ali N, Jaussaud Nicolas, Ge Liang, Chitsaz Sam, Chuter Timothy AM, Tseng Elaine E. Valve-in-Valve Hemodynamics of 20-Mm Transcatheter Aortic Valves in Small Bioprostheses. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2011;92:548–55. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Azadani Ali N, Tseng Elaine E. Transcatheter Heart Valves for Failing Bioprostheses: State-of-the-Art Review of Valve-in-Valve Implantation. Circulation: Cardiovascular Interventions. 2011;4:621–28. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.111.964478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bailey J, Curzen N, Bressloff NW. Assessing the Impact of Including Leaflets in the Simulation of Tavi Deployment into a Patient-Specific Aortic Root. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Engin. 2015:1–12. doi: 10.1080/10255842.2015.1058928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bapat VN, Attia R, Thomas M. Effect of Valve Design on the Stent Internal Diameter of a Bioprosthetic Valve a Concept of True Internal Diameter and Its Implications for the Valve-in-Valve Procedure. Jacc-Cardiovascular Interventions. 2014;7:115–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2013.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bianchi M, Ghosh RP, Marom G, Slepian MJ, Bluestein D. Simulation of Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement in Patient-Specific Aortic Roots: Effect of Crimping and Positioning on Device Performance. Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), 2015 37th Annual International Conference of the IEEE; 2015. pp. 282–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Capelli C, Bosi GM, Cerri E, Nordmeyer J, Odenwald T, Bonhoeffer P, Migliavacca F, Taylor AM, Schievano S. Patient-Specific Simulations of Transcatheter Aortic Valve Stent Implantation. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2012;50:183–92. doi: 10.1007/s11517-012-0864-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daneshvar SA, Rahimtoola SH. Valve Prosthesis-Patient Mismatch (Vp-Pm) a Long-Term Perspective. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2012;60:1123–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Buhr Wiebke, Pfeifer Stefan, Slotta-Huspenina Julia, Wintermantel Erich, Lutter Georg, Goetz Wolfgang A. Impairment of Pericardial Leaflet Structure from Balloon-Expanded Valved Stents. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Delgado V, Kapadia S, Schalij MJ, Schuijf JD, Tuzcu EM, Bax JJ. Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation: Implications of Multimodality Imaging in Patient Selection, Procedural Guidance, and Outcomes. Heart. 2012;98:743–54. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2011-301060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Detaint D, Lepage L, Himbert D, Brochet E, Messika-Zeitoun D, Iung B, Vahanian A. Determinants of Significant Paravalvular Regurgitation after Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation Impact of Device and Annulus Discongruence. Jacc-Cardiovascular Interventions. 2009;2:821–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dewey Todd M, Brown David, Ryan William H, Herbert Morley A, Prince Syma L, Mack Michael J. Reliability of Risk Algorithms in Predicting Early and Late Operative Outcomes in High-Risk Patients Undergoing Aortic Valve Replacement. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2008;135:180–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Di Martino LFM, Vletter WB, Ren B, Schultz C, Van Mieghem NM, Soliman OII, Di Biase M, de Jaegere PP, Geleijnse ML. Prediction of Paravalvular Leakage after Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation. International Journal of Cardiovascular Imaging. 2015;31:1461–68. doi: 10.1007/s10554-015-0703-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dijkman Petra E, Driessen-Mol Anita, de Heer Linda M, Kluin Jolanda, van Herwerden Lex A, Odermatt Berhard, Baaijens FP, Hoerstrup Simon P. Trans-Apical Versus Surgical Implantation of Autologous Ovine Tissue-Engineered Heart Valves. The Journal of heart valve disease. 2012;21:670–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Driessen-Mol Anita, Emmert Maximilian Y, Dijkman Petra E, Frese Laura, Sanders Bart, Weber Benedikt, Cesarovic Nikola, Sidler Michele, Leenders Jori, Jenni Rolf. Transcatheter Implantation of Homologous “Off-the-Shelf” Tissue-Engineered Heart Valves with Self-Repair Capacity: Long-Term Functionality and Rapid in Vivo Remodeling in Sheep. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2014;63:1320–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.09.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ducci A, Tzamtzis S, Mullen MJ, Burriesci G. Hemodynamics in the Valsalva Sinuses after Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation (Tavi) Journal of Heart Valve Disease. 2013;22:688–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dumesnil Jean G, Pibarot Philippe. Prosthesis-Patient Mismatch: An Update. Current cardiology reports. 2011;13:250–7. doi: 10.1007/s11886-011-0172-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dvir D. Treatment of Small Surgical Valves Clinical Considerations for Achieving Optimal Results in Valve-in-Valve Procedures. Jacc-Cardiovascular Interventions. 2015;8:2034–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2015.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dvir D, Leipsic J, Blanke P, Ribeiro HB, Kornowski R, Pichard A, Rodes-Cabau J, Wood DA, Stub D, Ben-Dor I, Maluenda G, Makkar RR, Webb JG. Coronary Obstruction in Transcatheter Aortic Valve-in-Valve Implantation Preprocedural Evaluation, Device Selection, Protection, and Treatment. Circulation-Cardiovascular Interventions. 2015;8:10. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.114.002079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dvir D, Webb JG. Transcatheter Aortic Valve-in-Valve Implantation for Patients with Degenerative Surgical Bioprosthetic Valves. Circulation Journal. 2015;79:695–703. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-14-1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dvir D, Webb JG, Bleiziffer S, Pasic M, Waksman R, Kodali S, Barbanti M, Latib A, Schaefer U, Rodes-Cabau J, Treede H, Piazza N, Hildick-Smith D, Himbert D, Walther T, Hengstenberg C, Nissen H, Bekeredjian R, Presbitero P, Ferrari E, Segev A, de Weger A, Windecker S, Moat NE, Napodano M, Wilbring M, Cerillo AG, Brecker S, Tchetche D, Lefevre T, De Marco F, Fiorina C, Petronio AS, Teles RC, Testa L, Laborde JC, Leon MB, Kornowski R Valve In Valve Int Data, Registry. Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation in Failed Bioprosthetic Surgical Valves. Jama-Journal of the American Medical Association. 2014;312:162–70. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.7246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dvir Danny, Eltchaninoff Helene, Ye Jian, Kan Arohumam, Durand Eric, Bizios Anna, Cheung Anson, Aziz Mina, Simonato Matheus, Tron Christophe, Arbel Yaron, Moss Robert, Leipsic Jonathon, Ofek Hadas, Perlman Gidon, Barbanti Marco, Seidman Michael A, Blanke Philippe, Yao Robert, Boone Robert, Lauck Sandra, Lichtenstein Sam, Wood David, Cribier Alain, Webb John. EuroPCR. Paria: 2016. First Look at Long-Term Durability of Transcatheter Heart Valves: Assessment of Valve Function up to 10-Years after Implantation. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eggebrecht H, Schafer U, Treede H, Boekstegers P, Babin-Ebell J, Ferrari M, Mollmann H, Baumgartner H, Carrel T, Kahlert P, Lange P, Walther T, Erbel R, Mehta RH, Thielmann M. Valve-in-Valve Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation for Degenerated Bioprosthetic Heart Valves. Jacc-Cardiovascular Interventions. 2011;4:1218–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2011.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Emmert Maximilian Y, Weber Benedikt, Wolint Petra, Behr Luc, Sammut Sebastien, Frauenfelder Thomas, Frese Laura, Scherman Jacques, Brokopp Chad E, Templin Christian. Stem Cell–Based Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation: First Experiences in a Pre-Clinical Model. JACC: Cardiovascular interventions. 2012;5:874–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2012.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gavina C, Goncalves A, Almeria C, Hernandez R, Leite-Moreira A, Rocha-Goncalves F, Zamorano J. Determinants of Clinical Improvement after Surgical Replacement or Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation for Isolated Aortic Stenosis. Cardiovascular Ultrasound. 2014;12:10. doi: 10.1186/1476-7120-12-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Genereux P, Head SJ, Hahn R, Daneault B, Kodali S, Williams MR, van Mieghem NM, Alu MC, Serruys PW, Kappetein AP, Leon MB. Paravalvular Leak after Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement the New Achilles’ Heel? A Comprehensive Review of the Literature. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2013;61:1125–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.08.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gooley RP, Cameron JD, Meredith IT. Assessment of the Geometric Interaction between the Lotus Transcatheter Aortic Valve Prosthesis and the Native Ventricular Aortic Interface by 320-Multidetector Computed Tomography. Jacc-Cardiovascular Interventions. 2015;8:740–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gotzmann M, Korten M, Bojara W, Lindstaedt M, Rahlmann P, Mugge A, Ewers A. Long-Term Outcome of Patients with Moderate and Severe Prosthetic Aortic Valve Regurgitation after Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation. American Journal of Cardiology. 2012;110:1500–06. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grases F élix, Sanchis Pilar, Costa-Bauzá Antonia, Bonnin Oriol, Isern Bernat, Perelló Joan, Prieto Rafael M. Phytate Inhibits Bovine Pericardium Calcification in Vitro. Cardiovascular Pathology. 17:139–45. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grbic S, Mansi T, Ionasec R, Voigt I, Houle H, John M, Schoebinger M, Navab N, Comaniciu D. Image-Based Computational Models for Tavi Planning: From Ct Images to Implant Deployment. Med Image Comput Comput Assist Interv. 2013;16:395–402. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-40763-5_49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Groves EM, Falahatpisheh A, Su JL, Kheradvar A. The Effects of Positioning of Transcatheter Aortic Valve on the Fluid Dynamics of the Aortic Root. ASAIO J. 2014;60:545–52. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000000107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gunning PS, Saikrishnan N, McNamara LM, Yoganathan AP. An in Vitro Evaluation of the Impact of Eccentric Deployment on Transcatheter Aortic Valve Hemodynamics. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 2014;42:1195–206. doi: 10.1007/s10439-014-1008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gunning PS, Vaughan TJ, McNamara LM. Simulation of Self Expanding Transcatheter Aortic Valve in a Realistic Aortic Root: Implications of Deployment Geometry on Leaflet Deformation. Ann Biomed Eng. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s10439-014-1051-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gurvitch Ronen, Cheung Anson, Ye Jian, Wood David A, Willson Alexander B, Toggweiler Stefan, Binder Ronald, Webb John G. Transcatheter Valve-in-Valve Implantation for Failed Surgical Bioprosthetic Valves. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2011;58:2196–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hakki AH, Iskandrian AS, Bemis CE, Kimbiris D, Mintz GS, Segal BL, Brice C. A Simplified Valve Formula for the Calculation of Stenotic Cardiac-Valve Areas. Circulation. 1981;63:1050–55. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.63.5.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hansson NC, Thuesen L, Hjortdal VE, Leipsic J, Andersen HR, Poulsen SH, Webb JG, Christiansen EH, Rasmussen LE, Krusell LR, Terp K, Klaaborg KE, Tang M, Lassen JF, Botker HE, Norgaard BL. Three-Dimensional Multidetector Computed Tomography Versus Conventional 2-Dimensional Transesophageal Echocardiography for Annular Sizing in Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement: Influence on Postprocedural Paravalvular Aortic Regurgitation. Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions. 2013;82:977–86. doi: 10.1002/ccd.25005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hatoum H, Crestanello JA, Dasi LP. Possible Subclinical Leaflet Thrombosis in Bioprosthetic Aortic Valves. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016;374:1591–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1600179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hemmann Katrin, Sirotina Margarita, De Rosa Salvatore, Ehrlich Joachim R, Fox Henrik, Weber Johannes, Moritz Anton, Zeiher Andreas M, Hofmann Ilona, Sch ächinger Volker, Doss Mirko, Sievert Horst, Fichtlscherer Stephan, Lehmann Ralf. The Sts Score Is the Strongest Predictor of Long-Term Survival Following Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation, Whereas Access Route (Transapical Versus Transfemoral) Has No Predictive Value Beyond the Periprocedural Phase. Interactive CardioVascular and Thoracic Surgery. 2013;17:359–64. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivt132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hoffmayer KS, Zellner C, Kwan DM, Konety S, Foster E, Moore P, Yeghiazarians Y. Closure of a Paravalvular Aortic Leak with the Use of 2 Amplatzer Devices and Real-Time 2-and 3-Dimensional Transesophageal Echocardiography. Texas Heart Institute Journal. 2011;38:81–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Iqbal J, Serruys PW. Comparison of Medtronic Corevalve and Edwards Sapien Xt for Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation the Need for an Imaging-Based Personalized Approach in Device Selection. Jacc-Cardiovascular Interventions. 2014;7:293–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2014.01.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jabbour A, Ismail TF, Moat N, Gulati A, Roussin I, Alpendurada F, Park B, Okoroafor F, Asgar A, Barker S, Davies S, Prasad SK, Rubens M, Mohiaddin RH. Multimodality Imaging in Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation and Post-Procedural Aortic Regurgitation Comparison among Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, Cardiac Computed Tomography, and Echocardiography. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2011;58:2165–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jilaihawi H, Asgar A, Bonan R. Good Outcome and Valve Function Despite Medtronic-Corevalve Underexpansion. Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions. 2010;76:1022–25. doi: 10.1002/ccd.22648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.John Daniel, Buellesfeld Lutz, Yuecel Seyrani, Mueller Ralf, Latsios Georg, Beucher Harald, Gerckens Ulrich, Grube Eberhard. Correlation of Device Landing Zone Calcification and Acute Procedural Success in Patients Undergoing Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantations with the Self-Expanding Corevalve Prosthesis. JACC: Cardiovascular interventions. 2010;3:233–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2009.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kappetein A Pieter, Head Stuart J, Généreux Philippe, Piazza Nicolo, Van Mieghem Nicolas M, Blackstone Eugene H, Brott Thomas G, Cohen David J, Cutlip Donald E, van Es Gerrit-Anne. Updated Standardized Endpoint Definitions for Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation: The Valve Academic Research Consortium-2 Consensus Document. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2012;60:1438–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kheradvar A, Falahatpisheh A. The Effects of Dynamic Saddle Annulus and Leaflet Length on Transmitral Flow Pattern and Leaflet Stress of a Bi-Leaflet Bioprosthetic Mitral Valve. J Heart Valve Dis. 2012;21:225–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kheradvar A, Groves EL, Tseng EE. Proof of Concept of Foldavalve a Novel 14fr Totally Repositionable and Retrievable Transcatheter Aortic Valve. Euro Intervention. 2015;10 doi: 10.4244/EIJY15M03_04. pii: 20141002–01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kheradvar A, Groves EL, Tseng EE. Proof of Concept of Foldavalve a Novel 14fr Totally Repositionable and Retrievable Transcatheter Aortic Valve. Euro Intervention. 2015;10 doi: 10.4244/EIJY15M03_04. pii: 20141002–01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kheradvar A, Kasalko J, Johnson D, Gharib M. An in-Vitro Study of Changing Profile Heights in Mitral Bioprostheses and Their Influence on Flow. ASAIO J. 2006;52:34–38. doi: 10.1097/01.mat.0000191203.09932.8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kheradvar Arash, Groves Elliott M, Dasi Lakshmi P, Alavi S Hamed, Tranquillo Robert, Grande-Allen K Jane, Simmons Craig A, Griffith Boyce, Falahatpisheh Ahmad, Goergen Craig J, Mofrad Mohammad RK, Baaijens Frank, Little Stephen H, Canic Suncica. Emerging Trends in Heart Valve Engineering: Part I. Solutions for Future. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 2014;43:833–43. doi: 10.1007/s10439-014-1209-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kheradvar Arash, Groves Elliott M, Goergen Craig J, Alavi S Hamed, Tranquillo Robert, Simmons Craig A, Dasi Lakshmi P, Grande-Allen K Jane, Mofrad Mohammad RK, Falahatpisheh Ahmad, Griffith Boyce, Baaijens Frank, Little Stephen H, Canic Suncica. Emerging Trends in Heart Valve Engineering: Part Ii. Novel and Standard Technologies for Aortic Valve Replacement. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 2015;43:844–57. doi: 10.1007/s10439-014-1191-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Khoffi F, Heim F, Chakfe N, Lee JT. Transcatheter Fiber Heart Valve: Effect of Crimping on Material Performances. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2014 doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.33330. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kiefer Philipp, Gruenwald Felix, Kempfert Joerg, Aupperle Heike, Seeburger Joerg, Mohr Friedrich Wilhelm, Walther Thomas. Crimping May Affect the Durability of Transcatheter Valves: An Experimental Analysis. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2011;92:155–60. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Klotz Stefan, Scharfschwerdt Michael, Richardt Doreen, Sievers Hans H. Failed Valve-in-Valve Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation. JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions. 2012;5:591–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2012.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kodali SK, Williams MR, Smith CR, Svensson LG, Webb JG, Makkar RR, Fontana GP, Dewey TM, Thourani VH, Pichard AD, Fischbein M, Szeto WY, Lim S, Greason KL, Teirstein PS, Malaisrie SC, Douglas PS, Hahn RT, Whisenant B, Zajarias A, Wang DL, Akin JJ, Anderson WN, Leon MB Investigators, Partner Trial. Two-Year Outcomes after Transcatheter or Surgical Aortic-Valve Replacement. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;366:1686–95. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Koos Ralf, Mahnken Andreas Horst, Dohmen Guido, Brehmer Kathrin, Günther Rolf W, Autschbach Rüdiger, Marx Nikolaus, Hoffmann Rainer. Association of Aortic Valve Calcification Severity with the Degree of Aortic Regurgitation after Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation. International Journal of Cardiology. 2011;150:142–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kumar Gautam, Raghav Vrishank, Lerakis Stamatios, Yoganathan Ajit P. High Transcatheter Valve Replacement May Reduce Washout in the Aortic Sinuses: An in-Vitro Study. The Journal of heart valve disease. 2015;24:22–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Latib A, Naganuma T, Abdel-Wahab M, Danenberg H, Cota L, Barbanti M, Baumgartner H, Finkelstein A, Legrand V, de Lezo JS, Kefer J, Messika-Zeitoun D, Richardt G, Stabile E, Kaleschke G, Vahanian A, Laborde JC, Leon MB, Webb JG, Panoulas VF, Maisano F, Alfieri O, Colombo A. Treatment and Clinical Outcomes of Transcatheter Heart Valve Thrombosis. Circulation-Cardiovascular Interventions. 2015;8:12. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.114.001779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Leber AW, Eichinger W, Rieber J, Lieber M, Schleger S, Ebersberger U, Deichstetter M, Vogel J, Helmberger T, Antoni D, Riess G, Hoffmann E, Kasel AM. Msct Guided Sizing of the Edwards Sapien Xt Tavi Device: Impact of Different Degrees of Oversizing on Clinical Outcome. International Journal of Cardiology. 2013;168:2658–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Leber Alexander W, Kasel Markus, Ischinger Thomas, Ebersberger Ulrich H, Antoni Diethmar, Schmidt Martin, Riess Gotthard, Renz Vivian, Huber Armin, Helmberger Thomas, Hoffmann Ellen. Aortic Valve Calcium Score as a Predictor for Outcome after Tavi Using the Corevalve Revalving System. International Journal of Cardiology. 2013;166:652–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.11.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Leipsic J, Yang TH, Min JK. Computed Tomographic Imaging of Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement for Prediction and Prevention of Procedural Complications. Circulation-Cardiovascular Imaging. 2013;6:597–605. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.113.000334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Leon Martin B, Smith Craig R, Mack Michael J, Makkar Raj R, Svensson Lars G, Kodali Susheel K, Thourani Vinod H, Tuzcu E Murat, Miller D Craig, Herrmann Howard C, Doshi Darshan, Cohen David J, Pichard Augusto D, Kapadia Samir, Dewey Todd, Babaliaros Vasilis, Szeto Wilson Y, Williams Mathew R, Kereiakes Dean, Zajarias Alan, Greason Kevin L, Whisenant Brian K, Hodson Robert W, Moses Jeffrey W, Trento Alfredo, Brown David L, Fearon William F, Pibarot Philippe, Hahn Rebecca T, Jaber Wael A, Anderson William N, Alu Maria C, Webb John G. Transcatheter or Surgical Aortic-Valve Replacement in Intermediate-Risk Patients. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016;374:1609–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1514616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lerakis S, Hayek SS, Douglas PS. Paravalvular Aortic Leak after Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement Current Knowledge. Circulation. 2013;127:397–407. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.142000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lerakis Stamatios, Hayek Salim S, Douglas Pamela S. Paravalvular Aortic Leak after Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement: Current Knowledge. Circulation. 2013;127:397–407. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.142000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li K, Sun W. Simulated Thin Pericardial Bioprosthetic Valve Leaflet Deformation under Static Pressure-Only Loading Conditions: Implications for Percutaneous Valves. Ann Biomed Eng. 2010;38:2690–701. doi: 10.1007/s10439-010-0009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Linke A, Woitek F, Merx MW, Schiefer C, Mobius-Winkler S, Holzhey D, Rastan A, Ender J, Walther T, Kelm M, Mohr FW, Schuler G. Valve-in-Valve Implantation of Medtronic Corevalve Prosthesis in Patients with Failing Bioprosthetic Aortic Valves. Circulation-Cardiovascular Interventions. 2012;5:689–97. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.112.972331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Litmanovich Diana E, Ghersin Eduard, Burke David A, Popma Jeffrey, Shahrzad Maryam, Bankier Alexander A. Imaging in Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement (Tavr): Role of the Radiologist. Insights into imaging. 2014;5:123–45. doi: 10.1007/s13244-013-0301-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Makkar RR, Fontana G, Jilaihawi H, Chakravarty T, Kofoed KF, de Backer O, Asch FM, Ruiz CE, Olsen NT, Trento A, Friedman J, Berman D, Cheng W, Kashif M, Jelnin V, Kliger CA, Guo H, Pichard AD, Weissman NJ, Kapadia S, Manasse E, Bhatt DL, Leon MB, Sondergaard L. Possible Subclinical Leaflet Thrombosis in Bioprosthetic Aortic Valves. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;373:2015–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1509233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Makkar RR, Fontana GP, Jilaihawi H, Kapadia S, Pichard AD, Douglas PS, Thourani VH, Babaliaros VC, Webb JG, Herrmann HC, Bavaria JE, Kodali S, Brown DL, Bowers B, Dewey TM, Svensson LG, Tuzcu M, Moses JW, Williams MR, Siegel RJ, Akin JJ, Anderson WN, Pocock S, Smith CR, Leon MB Investigators, Partner Trial. Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Replacement for Inoperable Severe Aortic Stenosis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;366:1696–704. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1202277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Makkar Raj R, Fontana Gregory, Jilaihawi Hasan, Chakravarty Tarun, Kofoed Klaus F, de Backer Ole, Asch Federico M, Ruiz Carlos E, Olsen Niels T, Trento Alfredo, Friedman John, Berman Daniel, Cheng Wen, Kashif Mohammad, Jelnin Vladimir, Kliger Chad A, Guo Hongfei, Pichard Augusto D, Weissman Neil J, Kapadia Samir, Manasse Eric, Bhatt Deepak L, Leon Martin B, Søndergaard Lars. Possible Subclinical Leaflet Thrombosis in Bioprosthetic Aortic Valves. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;373:2015–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1509233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Martin C, Pham T, Sun W. Significant Differences in the Material Properties between Aged Human and Porcine Aortic Tissues. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;40:28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2010.08.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Martin C, Sun W. Comparison of Transcatheter Aortic Valve and Surgical Bioprosthetic Valve Durability: A Fatigue Simulation Study. J Biomech. 2015;48:3026–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2015.07.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]