Abstract

Background

Obesity continues to be a serious public health challenge. Rates are increasing worldwide, with nearly 70% of US adults overweight or obese, leading to increased clinical and economic burden. While successful approaches for achieving weight loss have been identified, techniques for long-term maintenance of initial weight loss have largely been unsuccessful. Financial incentive interventions have been shown in several settings to be successful in motivating participants to adopt healthy behaviors.

Purpose

Keep It Off is a three-arm randomized controlled trial that compares the efficacy of a lottery-based incentive, traditional direct payment incentive, and control of daily feedback without any incentive, for weight loss maintenance. This design allows comparison of a traditional direct payment incentive with one based on behavioral economic principles that consider the underlying psychology of decision-making.

Methods

Participants were randomized in a 2:1 ratio for each active arm relative to control, with a targeted 188 participants total. Eligible participants were those aged 30–80 who lost at least 11 pounds (lb, 5 kilograms (kg)) during the first 4 months of participation in Weight Watchers, a national weight loss program, with whom we partnered. The interventions lasted 6 months (Phase I); participants were followed for 6 additional months without intervention (Phase II). The primary outcome is weight change from baseline to the end of Phase I, with the change at the end of Phase II a key secondary endpoint. Keep It Off is a pragmatic trial that recruited, consented, enrolled and followed patients electronically. Participants were provided a wireless weight scale that electronically transmitted daily self-monitored weights. Weights were verified every 3 months at a Weight Watchers center local to the participant and electronically transmitted.

Results

Using the study web-based platform, we integrated recruitment, enrollment and follow-up procedures into a digital platform that required little staff effort to implement and manage. We randomized 191 participants in less than one year. We describe the design of Keep It Off and implementation of enrollment.

Lessons Learned

We demonstrated that our pragmatic design was successful in rapid accrual of participants in a trial of interventions to maintain weight loss.

Limitations

Despite the nationwide reach of Weight Watchers, the generalizability of study findings may be limited by the characteristics of its members. The interventions under study are appropriate for settings where an entity, such as an employer or health insurance company, could offer them as a benefit.

Conclusions

Keep It Off was implemented and conducted with minimal staff effort. This study has the potential to identify a practical and effective weight loss maintenance strategy.

Keywords: Behavioral economics, financial incentive, obesity, pragmatic trial, randomized trial, weight loss maintenance

Introduction

Obesity is a growing problem, with worldwide incidence doubling since 1980.1 In the United States, approximately 70% of adults are overweight or obese. Excess body fat has been associated with increased risk of heart disease, stroke, diabetes, certain cancers and early mortality.2,3 Obesity also has significant economic consequences with direct medical costs, higher rates of disability and decreased job productivity.4,5 Given this clinical and economic burden, identifying effective strategies to reduce body weight is a public health imperative.

While successful approaches for achieving initial weight loss have been identified,6,7 techniques for long-term weight loss maintenance have been more elusive. Several studies reporting weight loss at 6 months found 25–60% of that weight regained at 12 months.8 Weight regain after a period of intentional weight loss is widely observed due to reasons such as loss of motivation, lack of sustained rewards for weight loss behavior, difficulty adhering to diet, and willpower depletion.9–11

An external motivational source such as financial incentives may help people keep weight off more effectively than standard approaches. Individuals put disproportionate value on the present relative to future costs and benefits, a phenomenon known as present-biased preferences.12 While this bias typically works against healthy behavior, the same factors can be used to promote compliance by providing tangible but small immediate rewards for beneficial behaviors. A review of 11 randomized trials found that financial incentives promoted adherence better than any tested alternative, leading to better blood pressure control and appointment attendance and higher immunization rates.13 As shown in recent work by our group, financial incentives are effective in inducing initial weight loss.14–16

Few studies, however, have examined longer-term effects of incentives on health behaviors after incentives stop, or the relative effectiveness of traditional economic versus behavioral economic incentives, such as lottery schemes that consider the underlying psychology of decision-making. Keep It Off provides an innovative test of the relative effectiveness of lottery-based financial incentives, traditional financial incentives, and daily feedback on maintenance of weight loss. After the intervention phase, participants in all arms were observed without intervention to evaluate the longer-term effects on weight-loss maintenance after cessation of the incentives.

The study was conducted using a web-based platform that facilitated participant recruitment, consent, enrollment, communication, follow-up and reimbursement. The data collection procedures leveraged existing electronic infrastructure available to study participants and required no on-site study visits. Thus, this study was a pragmatic trial in that the intervention was embedded within the participant’s home environment, including their membership in a participating Weight Watchers center.17 We highlight the unique design of Keep It Off and provide perspectives on the successes and challenges we experienced.

Methods

Overview of design and study objectives

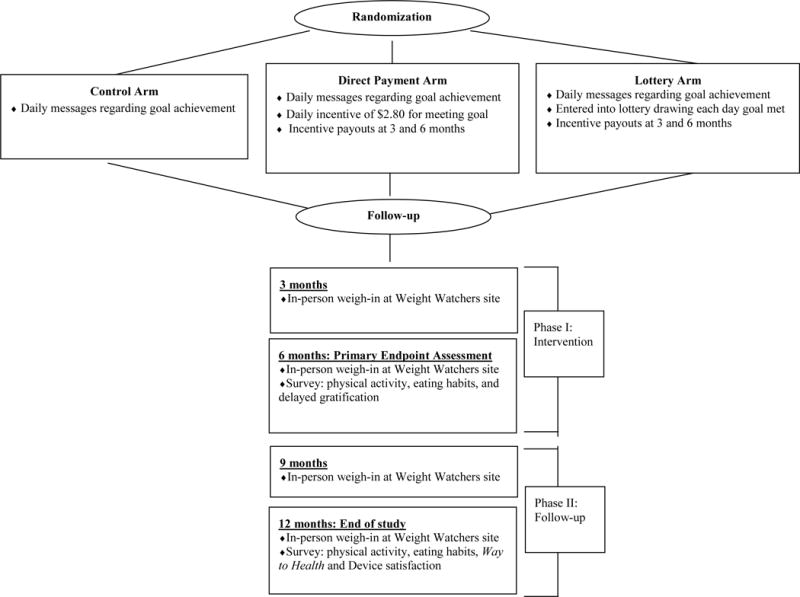

Keep It Off is a 3-arm, unblinded randomized controlled trial (RCT) with two phases, an intervention phase (Phase I) and a follow-up phase (Phase II). In Phase I, individuals who lost at least 11 pounds (lb, 5 kilograms (kg)) in the first 4 months of a Weight Watchers weight-loss program were randomized to receive one of the following interventions for 6 months: 1) daily weigh-ins and daily feedback (control), 2) control intervention + a lottery-based financial incentive (lottery), or 3) control intervention + a financial incentive consisting of traditional direct payments (direct payment). Those in the lottery arm were eligible to win daily lotteries for each day they achieved weight goals, whereas those assigned to the direct payment arm received a daily payment equal to the expected winnings of the lottery for each day they achieved weight goals (details below). In Phase II, months 7–12, all participants were followed without intervention. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Pennsylvania.

The primary objectives of this study are the three possible arm comparisons of weight loss maintenance at the end of Phase I (month 6). As a secondary objective, we assess the degree to which weight loss was maintained in the intervention groups relative to control during the 6 months following cessation of the interventions (Phase II).

Participant eligibility and recruitment process

To facilitate recruitment, we chose to enroll study participants from Weight Watchers, the largest weight loss program nationally with over 1 million members. Recruitment was limited to members who had opted to receive notifications about research studies (approximately 65% of members) and who belonged to a CHAMP (Computerized History and Member Processing)-enabled meeting center, which allowed for in-person weigh-in data collected at the Weight Watchers center during follow-up to be transmitted to the study database. Five hundred five CHAMP centers located in 41 states were selected for a targeted enrollment of 188 participants over a 1-year period.

Eligible participants were men and women aged 30 to 80 years who had a body mass index (BMI) of 30 to 45 kg/m2 prior to starting Weight Watchers, joined Weight Watchers and had a documented weight loss of at least 11 lb in the past 4 months, and were in stable health. People in this age range are those most affected by obesity in terms of prevalence, associated disease, disability, and healthcare costs.18,19 Participants had to have reliable access to the Internet, and an iPhone (OS 5.0 or later) or Android phone (OS 2.3.3 or later), to be paired successfully with the Withings wireless weight scale. This scale was provided by the study team to all enrolled participants to enable wireless transmission to the study database of weights measured daily at home during follow-up.

Exclusion criteria were limited to factors that could confound results or make participation in a weight loss program infeasible, unsafe, or require more intensive monitoring.20 Exclusion criteria included substance abuse; bulimia nervosa or related behaviors; pregnancy or breast feeding; medical contraindications to counseling about diet, physical activity, or weight reduction; unstable mental illness; screen positive for pathologic gambling on the basis of the two question Lie/Bet Questionnaire (excluded if answers yes to either question).21 Individuals unable to provide consent or fill out surveys in English were excluded.

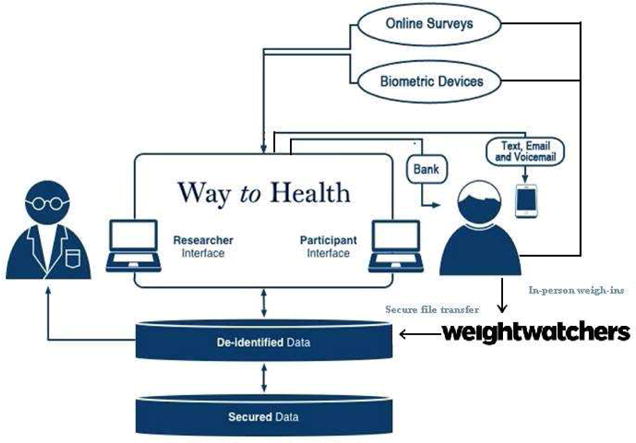

Recruitment emails were sent in monthly waves by Weight Watchers to all members Weight Watchers identified at the time as having met the age, BMI, and weight loss eligibility criteria. An initial email and at least one bi-weekly reminder were sent to potentially eligible members inviting them to visit the Way to Health (WTH) portal, a web-based clinical study platform hosted by the University of Pennsylvania and sponsored by the National Institutes of Health,16,22 to learn more about the study and to participate. WTH integrates clinical trial enrollment and randomization processes, receipt of data from wireless devices (such as the Withings scale), messaging (text, email, or voice), self-administered surveys, distribution of financial incentives, and patient communication.16,23–28

Participants completed an online eligibility screening form and online consent. Participants were instructed to weigh in at the nearest Weight Watchers CHAMP location to verify the 11 lb weight loss requirement. Once verified, participants received an automated message prompting them to complete the baseline survey. Upon completion, participants were sent a Withings scale. Participants had 2 months to complete enrollment. To avoid randomizing participants who were unable to use the device, participants were randomized after the first weight transmission. Immediately following randomization, participants received notification to log into the WTH portal to receive their randomization assignment.

The WTH portal allowed the study team to track participant enrollment. Participants remaining at any enrollment step for more than a few days received a message encouraging them to continue. WTH also provided a two-way communication channel for participants to send inquires to the study team throughout the study. Figure 1 summarizes the flow of information between the participant, Weight Watchers, and the study database.

Figure 1.

Keep It Off flow of study information through the Way to Health Platform.

Interventions

Randomized participants selected a weekly weight loss goal of 0, 0.5, or 1 lb and self-monitored their weights daily using the Withings scale, which transmits daily weights wirelessly to the study database. Participants in each intervention group received a daily message with feedback from the WTH Platform on their progress relative to their goals. Participants in both incentive arms were eligible for daily winnings based on transmitted weights. They received daily feedback on their winnings to keep weight goals salient; however, payments were based on required in-person weigh-ins at months 3 and 6, to take advantage of the motivating power of loss aversion by highlighting to participants that they would only receive their accumulated daily winnings if they continued to meet their goal and reach the target weight for their milestone visit. Between months 7–12 (Phase II) participants received no further daily incentives.

The lottery incentive was designed to provide both infrequent large payoffs and frequent small payoffs because individuals are motivated by both the future, being particularly attracted to small probabilities of large rewards, and the past (how often did I win?).29–31 This lottery incentive scheme has been shown to be successful in the primary weight loss setting.15 With this incentive, a participant who met his/her weight target could win $10 (18 in 100 chance) or $100 (1 in 100 chance). When a participant did not complete the daily weigh-in or weighed in above the target, the participant received a message indicating she would have won the lottery that day if a weight had been transmitted and was at or below target. We hypothesize that a desire to avoid the regret associated with not winning, combined with learning that one would have won had one been adherent, would motivate participants to a greater degree than the value of the rewards alone.

Direct payment participants were eligible to receive $2.80 (the expected winnings of the lottery) each day they weighed in and were at or below their weight loss goals. There was no regret component to this arm, as our goal is to compare the impact of a behavioral economic incentive to a straightforward economic incentive that is easier to administer.

The weight loss/maintenance trajectory for all arms could be reset monthly, a critical feature when a participant fell short of attaining a monthly weight loss goal in order to avoid discouraging participants who would otherwise have had to lose a lot of weight to get back on track and potentially have dropped out of the study. However, the choice was limited to the 0.5 and 1 lb per week weight loss option whenever a participant’s current weight exceeded the study start weight. Receipt of each participant’s cumulative daily incentives were contingent on completing the verification weigh-ins in person at months 3 and 6. Winnings were prorated on the percent of goal achieved, as determined by their verified weight. To receive 100% of their winnings, participants had to be at or below their goal.

All participants were compensated up to $160 for their time, with $30 for completing each of the 3 and 9 month in-person weigh-ins and $50 each for completing the 6 and 12 in-person weigh-ins. This strategy had succeeded in minimizing differential dropout in our previous studies of different financial incentives.14,15 All participants eligible for Phase I received a free weight scale (retail value $179) upon enrollment that they kept at the end of the study.

Follow-up procedures

Participants were asked to weigh themselves each morning using the internet-enabled scale. At 3, 6, 9 and 12 months after randomization, participants were asked to go to a Weight Watcher’s CHAMP location to provide in-person weight data, which was recorded electronically as part of usual member services. Participants who chose to weigh-in more often than required by the trial protocol had weight data sent more frequently. At 6 and 12 months, participants completed a questionnaire on WTH regarding physical activity, eating habits, and delayed gratification behaviors. At 12 months, participants provided information about their study experience and helpfulness of the intervention. See Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Keep It Off study schema.

The WTH platform included an automated participant tracking system that reminded the study coordinator of each participant’s quarterly weigh-in schedule. Customized messages were sent to encourage participants who were overdue for an in-person weigh-in.

Baseline weight and qualifying weight loss for all participants were ascertained at the beginning of Phase I. Weight change after randomization was ascertained at the end of months 3, 6, 9 and 12 based on weigh-ins at Weight Watchers centers.

Study monitoring

An independent Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) reviewed and approved the research protocol and plans for data and safety monitoring prior to the study start. The DSMB assessed data quality, participant recruitment, accrual, retention, and adverse events. Potential safety concerns prior to study start were maintaining participant privacy and monitoring to detect rapid, potentially unsafe weight loss. Procedures to address these concerns were described in the study’s Data Safety Monitoring Plan, approved by the DSMB before study start.

Patients were requested to report hospitalizations on the WTH portal or by phone calls to the study coordinator. Participants were monitored in real-time during follow-up for excessive weight loss, which triggered an alert. Excessive weight loss originally was defined as >5 lb in one week, 8 lb in 2 weeks, and/or 12 lb in a month. Two months into the study, the alerts were changed to a weekly trigger of >7 lb and/or 12 lb in one month, to reduce the number of unnecessary alerts arising from calibration issues or variation in how a participant weighed in (clothed or non-morning). The study coordinator called participants to determine whether they were engaging in unsafe behaviors to achieve goals. Completed excessive weight loss questionnaires were sent to the principal investigator for review. Weight loss alerts were summarized for DSMB review.

Statistical considerations

Participants were randomized in a 2:2:1 ratio with twice as many assigned to each financial incentive intervention compared to the control intervention using block randomization with variable block sizes. This design allowed for a more precisely estimated difference between the two financial incentive intervention arms, which was pre-hypothesized to be smaller than the difference between a financial incentive and control. Randomization was stratified by gender and degree of obesity at baseline (BMI 30–37.9 and 38–45 kg/m2). We planned to enroll 188 participants; allowing for a 20% loss to follow-up at 12-months, this yielded outcome data for an expected 150 participants.

The Holm-Bonferroni method is used to test the three primary comparisons to maintain the experiment-wide 0.05 type I error.32 150 participants provide at least 90% power to detect a difference in weight change during Phase I of 11 lb (5 kg) between each financial incentive group and the control and 6.6 lb (3 kg) between incentive groups, assuming a standard deviation for weight loss of 11 lb (5kg).

Primary analyses will be done on an intent-to-treat basis. We will impute missing 6-month in-person weights using a linear regression model built on baseline participant characteristics. In sensitivity analysis, we will assume that the weight of any participant with missing outcome weigh-ins returned to baseline.33 We will consider the sensitivity of the study findings to alternative imputation strategies that use post-randomization in-person and daily weights and adjustment for potential confounders. Analyses of secondary outcomes, including weight loss at 12 months, will be done in a similar manner.

Results

Recruitment and enrollment

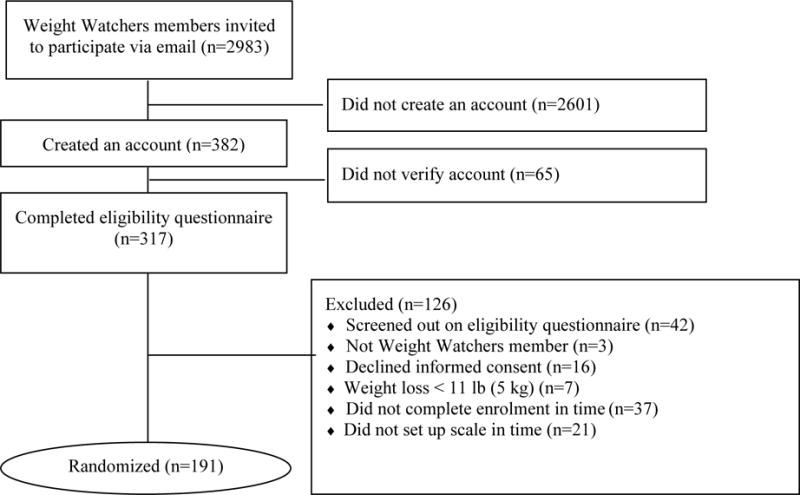

We randomized 191 participants from 158 Weight Watchers centers in less than 9 months. Candidates were recruited in 6 monthly cohorts by email message between September 2013 and May 2014. Weight Watchers sent at least two messages per cohort. Email messages were sent in three waves to the first two cohorts. The third email message resulted in very few additional enrollments, so the email frequency was changed to two waves per cohort.

Figure 3 summarizes the flow of potential participants from recruitment to randomization. A total of 2983 Weight Watchers members received an invitation email. Of these, 382 (12%) candidates created an account on the study website, but 65 failed to verify their accounts (a necessary step to initiate the online screening process) and 126 were ineligible, yielding 191 randomized participants. Ineligible individuals had the same percentage of males (9%) and were on average 3 years older compared to randomized participants. Phase I was completed on January 2, 2015; Phase II was completed on July 17, 2015. As of March 4, 2016, analyses of study data were in progress and will be reported separately.

Figure 3.

Keep It Off participant recruitment flow.

Challenges and lessons learned

A unique feature of this study was partnering with Weight Watchers, a national commercial provider of weight control services, to take advantage of their large representative membership, their records regarding members with recent weight loss, and their existing infrastructure that allowed us to capture member weigh-in data electronically. One challenge was that randomized participants were not required to maintain Weight Watchers membership. We arranged to issue to any participant who discontinued membership a voucher for access to a local Weight Watchers CHAMP center for scheduled weigh-ins. When necessary, participants were weighed at non-CHAMP centers and weights were faxed to study staff.

An important challenge for Keep It Off was achieving accrual goals while maintaining generalizability. We also needed to optimize participant recruitment for online communications, which can be plagued by low response rates – a challenge for generalizability and study budgets.34 Additional challenges to participant enrollment and collection of trial data included ability to assess participants’ electronic environment remotely to confirm eligibility and to remotely resolve technical issues with the participants’ wireless devices and internet connections.

We learned that the invitation email needed to clearly specify the source of the email, the purpose of the study, and the upfront time commitment required of participants. Feedback from potential participants indicated that the screening interaction could have been improved by more detail in the initial email message and emphasis that the messages came directly from the University of Pennsylvania study team. We also learned that we needed to refine the list of acceptable phones, and to solicit more detailed information for phone models from candidates before confirming eligibility and sending a weight scale. Information regarding specific versions of phone operating systems was needed to supplement the manufacturer’s specifications in order to assess phone compatibility. These are important considerations for any study designed to rely on personal smartphones or tablets and commercial wireless instruments for which software updates will be beyond the control of the study.

Instruments selected for use in Keep It Off included a commercially available weight scale with wireless capability to capture daily weights remotely. For a candidate to be enrolled successfully, software on the WTH Platform had to be configured to create a successful interface with the application program interface of the Withings scale so that weight data could transmit automatically once a participant set up the scale and authorized WTH to collect data. Participants were deemed ineligible if their scale was not set up by the 6-month mark of their Weight Watchers membership. Twenty-four participants received a scale but were unable or unwilling to set up their scale within the allotted time and thus were not enrolled. The ages of these participants ranged from 34 to 71 years; on average, they were about 5 years older than the successfully randomized participants.

By relying on the existing infrastructure of our industry partner and the existing WTH platform, this study was conducted with a small staff consisting of a full-time study coordinator, 50% of a data manager, and relatively small effort from a statistician, a clinical and principal investigator. Shared resource staff from WTH created and maintained the study database and assisted with data analysis. Weight Watchers staff received no reimbursement for their activities; their participation was motivated by a shared interest in the research.

Discussion

The Keep It Off study examines the efficacy of three interventions for weight loss maintenance, any one of which could serve as a model for work places or similar weight loss and maintenance programs. In particular, this study will provide information about whether and what type of financial incentive, if any, is more efficacious for weight loss maintenance compared to daily weight monitoring and feedback. An important study design element is our control arm of feedback alone, which will allow us to disentangle the effect of daily weight monitoring with feedback inherent in our incentive arms from that of the incentive itself.

This study has some limitations regarding generalizability. At enrollment, participants had to be Weight Watcher members at a CHAMP center. While geographically diverse, study participants reflected the predominantly female membership of Weight Watchers, needed sufficient financial resources to afford the Weight Watchers membership fee, and had to have an email address, Internet access, and a wireless phone compatible with the study weight scale. An additional limitation is that, as expected, we enrolled very few participants per site and did not stratify randomization by study site, allowing for potential imbalance by chance at some sites. There were 131 sites (83%) with one participant; the largest site had 4 study participants and none of the three intervention arms had more than 2 participants from a single site.

This study also had strengths. In particular, it was conducted pragmatically, in the context of the very operational system in which it could be later implemented. The design of this study reveals how real-time operational systems can become laboratories for health behavior change. By embedding the study into existing systems and relying on a primarily digital platform, we conducted the study with modest study-specific resources. This type of clinical trial design is well-suited for many behavioral interventions that could rely on electronic communication and self-monitoring devices, such as physical activity from step counters or portable accelerometers, pill bottles with electronic medication adherence monitors, or glycemic control from wireless devices. We also envisage that there are many potential partnerships with commercial or public entities, similar to the one we formed with Weight Watchers and others.27 Such partners can not only provide the efficiencies of existing infrastructure, but the ability to study pragmatic interventions that deliver both internal and external validity for the study findings.

In Keep It Off, we developed a pragmatic paradigm for the enrollment and conduct of weight loss and maintenance intervention studies. With relatively small staff, participants were recruited, enrolled, and followed, all with a passive electronic system augmented by tools that allowed for staff interaction through the use of email, phone calls, and text messages. In an era of diminishing research dollars for available studies, pragmatic designs that embed clinical research into settings with existing infrastructure have become a necessary imperative.35 We have shown that such pragmatic designs can be implemented successfully to evaluate interventions to achieve or maintain weight loss.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the study participants for their time and dedication to the study. We would also like to thank the staff at Weight Watchers for their assistance in recruiting participants and facilitating measurement of their follow-up weights at the pre-specified intervals for our study outcome.

Funding: Sponsored by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health, Award Number R01-AG045045 (Volpp and Yancy, MPIs).

Financial Disclosures

Kevin Volpp is a principal in the behavioral economics consulting firm VAL Health and has received consulting income and research funding from CVS as well as research support from Weight Watchers, Humana, Hawaii Medical Services Association, and Merck. Drs Shaw, Troxel, and Volpp have received research funding from the Vitality Institute. Dr. Troxel serves on the scientific advisory board of VAL Health. Dr. Foster is an employee of Weight Watchers International.

Footnotes

Trial Registration: clinicaltrials.gov Identifier NCT01900392

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight. Factsheet. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/ (accessed 18 August 2015)

- 2.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, et al. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2000. JAMA. 2002;288:1723–1727. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999–2004. JAMA. 2006;295:1549–1555. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Adult obesity causes & consequences. http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/adult/causes.html (accessed 18 August 2015)

- 5.Hammond RA, Levine R. The economic impact of obesity in the United States. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2010;3:285–295. doi: 10.2147/DMSOTT.S7384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nordmann AJ, Nordmann A, Briel M, et al. Effects of low-carbohydrate vs low-fat diets on weight loss and cardiovascular risk factors: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:285–293. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.3.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gardner CD, Kiazand A, Alhassan S, et al. Comparison of the Atkins, Zone, Ornish, and LEARN diets for change in weight and related risk factors among overweight premenopausal women: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2007;297:969–977. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.9.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Franz MJ, VanWormer JJ, Crain AL, et al. Weight-loss outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of weight-loss clinical trials with a minimum 1-year follow-up. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107:1755–1767. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jeffery RW, Drewnowski A, Epstein LH, et al. Long-term maintenance of weight loss: current status. Health Psychol. 2000;19(1 Suppl):5–16. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.19.suppl1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jeffery RW, Kelly KM, Rothman AJ, et al. The weight loss experience: a descriptive analysis. Ann Behav Med. 2004;27:100–106. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2702_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baumeister RF, Gailliot M, DeWall CN, et al. Self-regulation and personality: how interventions increase regulatory success, and how depletion moderates the effects of traits on behavior. J Pers. 2006;74:1773–1801. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2006.00428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Donoghue T, Rabin M. Doing it now or later. Am Econ Rev. 1999;89:103–124. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giuffrida A, Torgerson DJ. Should we pay the patient? Review of financial incentives to enhance patient compliance. BMJ. 1997;315:703–707. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7110.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.John L, Loewenstein G, Troxel AB, et al. Financial incentives for extended weight loss: a randomized, controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:621–626. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1628-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Volpp KG, John LK, Troxel AB, et al. Financial incentive-based approaches for weight loss: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2008;300:2631–2637. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kullgren JT, Troxel AB, Loewenstein G, et al. Individual-versus group-based financial incentives for weight loss: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:505–514. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-7-201304020-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roland M, Torgerson DJ. Understanding controlled trials: What are pragmatic trials? BMJ. 1998;316:285. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7127.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Finkelstein EA, Trogdon JG, Brown DS, et al. The lifetime medical cost burden of overweight and obesity: implications for obesity prevention. Obesity. 2008;16:1843–1848. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bales CW, Buhr G. Is obesity bad for older persons? A systematic review of the pros and cons of weight reduction in later life. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2008;9:302–312. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yancy WS, Jr, Westman EC, McDuffie JR, et al. A randomized trial of a low-carbohydrate, ketogenic diet versus orlistat plus a low-fat diet for weight loss. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:136–145. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson EE, Hamer R, Nora RM, et al. The lie/bet questionnaire for screening pathological gamblers. Psychol Rep. 1997;80:83–88. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1997.80.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Asch DA, Volpp KG. On the way to health. LDI Issue Brief. 2012;17:1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kullgren JT, Harkins KA, Bellamy SL, et al. A mixed-methods randomized controlled trial of financial incentives and peer networks to promote walking among older adults. Health Educ Behav. 2014;41(1 Suppl):43S–50S. doi: 10.1177/1090198114540464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sen AP, Sewell TB, Riley EB, et al. Financial incentives for home-based health monitoring: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29:770–777. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2778-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuna ST, Shuttleworth D, Chi L, et al. Web-based access to positive airway pressure usage with or without an initial financial incentive improves treatment use in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 2015;38:1229–1236. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Long JA, Jahnle EC, Richardson DM, et al. Peer mentoring and financial incentives to improve glucose control in African American veterans: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:416–424. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-156-6-201203200-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Halpern SD, French B, Small DS, et al. Randomized trial of four financial-incentive programs for smoking cessation. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2108–2117. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Asch DA, Troxel AB, Stewart WF, et al. Effect of financial incentives to physicians, patients, or both on lipid levels: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314:1926–1935. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.14850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Camerer C, Ho T-H. Experience-weighted attraction learning in normal form games. Econometrica. 1999;67:837–874. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Loewenstein G, Weber EU, Hsee CK, et al. Risk as feelings. Psychol Bull. 2001;127:267–286. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kahneman D, Tversky A. Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica. 1979;47:263–291. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holm S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scand J Statist. 1979;6:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ware JH. Interpreting incomplete data in studies of diet and weight loss. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2136–2137. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe030054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pequegnat W, Rosser BRS, Bowen AM, et al. Conducting Internet-based HIV/STD prevention survey research: Considerations in design and evaluation. AIDS Behav. 2007;11:505–521. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9172-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lauer MS. Time for a creative transformation of epidemiology in the United States. JAMA. 2012;308:1804–1805. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.14838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]