Abstract

Purpose of review

To provide an overview of anti-cancer therapies in various stages of clinical development as potential interventions to target HIV persistence

Recent findings

Epigenetic drugs developed for cancer have been investigated in vitro, ex vivo and in clinical trials as interventions aimed at reversing HIV latency and depleting the amount of virus that persists on antiretroviral therapy (ART). Treatment with histone deacetylase inhibitors induced HIV-expression in patients on ART but did not reduce the frequency of infected cells. Other interventions that may accelerate the decay of latently infected cells, in the presence or absence of latency-reversing therapy, are now being explored. These include apoptosis-promoting agents, non-HDACi compounds to reverse HIV latency and immunotherapy interventions to enhance antiviral immunity such as immune checkpoint inhibitors and toll-like receptor agonists.

Summary

A curative strategy in HIV will likely need to both reduce the amount of virus that persists on ART and improve anti-HIV immune surveillance. While we \continue to explore advances in the oncology field including cancer immunotherapy, there are major differences in the risk-benefit assessment between HIV infected and patients with malignancies. Drug development specifically targeting HIV persistence will be key to developing effective interventions with an appropriate safety profile.

Keywords: HIV latency, HIV reservoir, HIV cure, apoptosis-promoting agents, immune checkpoint inhibitors

Introduction

Although HIV infection and malignancies are fundamentally different disease processes, there are important similarities when considering strategies to cure HIV or allow for antiretroviral therapy (ART)-free remission. The primary barrier to curing HIV is the long-term persistence of replication-competent virus in latently infected cells in HIV-infected individuals on ART [1]. Latency occurs at a very low frequency of around 60 infected cells per million resting CD4+ T cells in peripheral blood and at higher frequency in lymphoid tissue [2, 3]. Other mechanisms may also contribute significantly to long-term viral persistence including infection of non-CD4+ T cells [4], clonal expansion of replication-competent proviruses [5], low-level residual replication in tissues with insufficient penetration of ART [6, 7] or persistence in tissue sites where cytotoxic T cells (CTLs) have restricted access, including lymph node follicles [8]. One of the key challenges in both cancer and HIV cure research is the development of assays that allow detection of the rare cells with the capacity to rekindle infection or cause relapsing malignant disease. Epigenetic modifying drugs, originally developed for uses in oncology, are being evaluated in HIV cure research as a mechanism to reverse HIV latency and drugs that promote apoptosis are being evaluated to deplete infected cells. Finally, the recent development of immune-based therapies in cancer such as immune checkpoint (IC) inhibitors is another area of converging interest, i.e. interventions to enhance the immune response against HIV or cancer antigens.

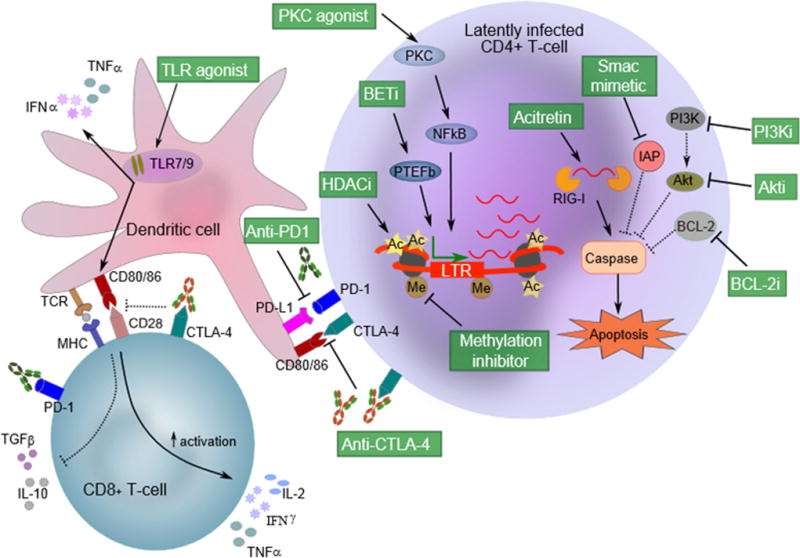

Here we provide an overview of therapies developed for treating malignancies, which are now being investigated as potential interventions to target HIV persistence (Table 1). We will discuss these approaches and the relevant mechanisms and offer our view on their potential applicability in the onward search for an HIV cure (summarised in Figure 1). Although bone marrow transplantation for haematological malignancy has had a clear profound effect on reducing the frequency of latently infected cells and also increased ART-free remission, these interventions will not be discussed here.

Table 1.

Cancer therapies investigated in HIV

| Drug class | Promising compounds in HIV research | Clinical development phase in oncology | Proposed effect in HIV infection | Clinical studies in HIV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| i. Latency reversing agents | ||||

|

| ||||

| HDAC inhibitors | Vorinostat, romidepsin, panobinostat | Licensed (CTCL, MM) | Reversing HIV latency by chromatin remodeling | Yes, refs 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 |

| BET inhibitors | OTX015, JQ1 | Phase I/II | Reversing HIV latency by promoting recruitment of P-TEFb to the HIV LTR | No |

| Histone methyltransferase inhibitors | Low doses only of chaetocin, BIX-01294 or DNZep | Not safe at doses tested / Pre-clinical | Prevents histone 3 methylation that represses HIV transcription, thereby reactivating latent HIV | No |

| DNA methyltransferase inhibitors | Azacitidine, decitabine | Licensed (MDS) | Prevents CpG methylation at the HIV promoter that represses HIV transcription | No |

| PKC agonists | Bryostatin-1, prostratin | Phase I/II | Reversing HIV latency by activating NF-κB signalling pathways | Yes, ref 17 |

|

| ||||

| ii. Apoptosis promoting compounds | ||||

|

| ||||

| Bcl-2 antagonists | Venetoclax | Licensed (CLL), Phase I-III | Inhibits anti-apoptotic BCL-2, sensitizing cells to apoptosis. When combined with LRA reactivation, leads to preferential apoptosis of HIV infected cells | No |

| RIG-I inducers | Acitretin | Licensed (psoriasis only) | Reactivates HIV transcription and activates RIG-I induced apoptosis, leading to selective apoptosis of HIV infected cells | No |

| PI3k/Akt inhibitors | Perifosine, arctigenin | Phase I/II | Blocks PI3K/Akt pathway signalling, sensitizing HIV-infected cells for apoptosis | No |

| SMAC mimetics | Birinipant, SBI-0637142, LCL161 | Phase I/II | Inhibits inhibitor of apoptosis proteins (IAPs), sensitizing HIV infected cells for apoptosis, inuduces viral replication | No |

| Tyrosine kinase inhibitors | Ibrutinib | Licensed | Impairs Bruton’s tyrosine kinase on the surface of HIV-infected cells, inducing selective depletion of HIV-infected cells | No |

|

| ||||

| iii. Immune modulation | ||||

|

| ||||

| Immune checkpoint inhibitors | Ipilimumab, pembrolizumab, nivolumab | Licensed (melanoma, NSCLC) | Enhancing HIV-specific T cell responses; reversing HIV latency | Yes, refs 60 |

| TLR agonists | GS-9620, MGN1703 | Phase I, II | Activating DCs and NK cells; reversing HIV latency | Yes, refs 76, 78 |

HDAC: histone deacetylase, CTCL: cutaneous T cell lymphoma, MM: multiple myeloma, BET: bromodomain and extra terminal, P-TEFb: positive transcription elongation factor b, MDS: myelodysplastic syndrome, PKC: protein kinase C, CLL: chronic lymphocytic leukemia, LRA: latency reversing agent, RIG-I: retinoic acid-inducible gene I, PI3k: phosphoinositide 3-kinase, SMAC:, second mitochondria-derived activator of caspase, NSCLC: non-small cell lung cancer, DC: dendritic cell, NK: natural killer.

Figure 1. Anti-cancer compounds with potential to target HIV persistence.

Latency reversing agents (LRAs) that induce HIV expression in latently infected cells include histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACi), bromodomain and extra-terminal (BET) inhibitors, methylation inhibitors and protein kinase C (PKC) agonists. HDACi promote histone acetylation and chromatin remodelling at the HIV promoter to support access for transcription initiation. Methylation inhibitors prevent deleterious hypermethylation of CpG islands near the HIV promoter to foster HIV transcription initiation. PKC agonists (eg. prostratin, bryostatin) promote the accumulation of active cellular NF-κB transcription factor in the cell nucleus to promote HIV transcription initiation. Bromodomain inhibitors (eg. JQ1) prevent PTEF-b binding to bromodomain proteins, releasing free PTEF-b to interact with HIV Tat protein for efficient HIV transcription elongation. Apoptosis-inducing compounds act on various pathways leading to caspase activation and apoptosis and could also be administered with LRAs to sensitise cells for apoptosis. For instance, acitretin triggers retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I) that in turn detects viral RNA for subsequent interferon-induced apoptosis. SMAC mimetics block inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) proteins, preventing IAPs from inhibiting apoptosis and sensitizing cells towards apoptosis. Similarly, inhibitors of BCL-2 (eg. Venetoclax) block this BCL-2 inhibitor of apoptosis, sensitising cells towards apoptosis. Inhibitors of the PI3K/Akt pro-survival pathway both culminate in preventing Akt activation (which inhibits apoptosis), thereby also sensitising cells towards apoptosis. Immune-based therapies such as immune checkpoint (IC) inhibitors and toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists may enhance immune-mediated killing of HIV-expressing cells. IC inhibitors (e.g. anti-PD1 or anti-CTLA-4) also block negative signalling to T cells and may potentially also reverse latency. TLR 7/9 agonists bind to receptors on endolysosomes in antigen-presenting cells and other immune cells, activate dendritic cells (DCs) and natural killer (NK) cells and induce release of interferon-α.

SMAC: second mitochondria-derived activator of caspase, PI3Ki: phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibitor, Akti: Akt inhibitor, BCL-2i: B-cell lymphoma 2 inhibitor, BETi: bromodomain and extra-terminal protein inhibitor, P-TEFb: positive transcription elongation factor b, LTR: HIV long terminal repeat promoter, Ac: acetylation, Me: methylation.

Histone deacetylase inhibitors

Using latency reversing agents (LRAs) to activate HIV production in latently infected cells and potentially facilitate their elimination through virus- or immune-mediated cell lysis has been proposed as a strategy to target persistent HIV. Histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACi), largely licensed for treating haematological malignancies, have now been studied in multiple small single-arm clinical trials as LRAs. The primary focus has been with vorinostat and romidepsin both approved for the treatment of cutaneous T cell lymphoma, and panobinostat, recently licensed for multiple myeloma. Early-phase clinical trials with vorinostat [9, 10], panobinostat [11] and romidepsin [12] have all demonstrated increases in HIV transcription, and in some cases also plasma HIV RNA. However, this did not reduce the frequency of latently infected CD4+ T cells. Current efforts are therefore focused on using HDACi in combination with other strategies that enhance HIV transcription, such as other epigenetic modifying drugs or with strategies that enhance HIV-specific immunity via therapeutic vaccination [13] (NCT02336074, NCT02616874), pegylated interferon (NCT02471430) and antigen loaded dendritic cells (NCT02707900).

Protein kinase C agonists

Activation of protein kinase C (PKC) with prostratin was originally shown to potently activate latent HIV in vitro [14], but given its toxicity it is uncertain whether this drug will proceed to clinical studies. Bryostatin-1 is another PKC agonist and is in clinical development for malignancies including multiple myeloma and renal cell carcinoma [15]. Bryostatin-1 activated HIV latency in resting CD4+ T cells from HIV-infected individuals on ART and when combined with potent HDACi displayed strong synergy and induced HIV production similar to maximal T cell stimulation [16]. However, a recent clinical trial using bryostatin-1 in HIV-infected individuals on ART did not demonstrate any effect on either PKC activity or HIV transcription, likely due to the low plasma concentrations observed with the doses used [17]. Ingenol derivatives also activate PKC isoforms, leading to increased NF-kB nuclear translocation and subsequent HIV RNA transcription. Ingenol B (IngB) was more efficient in inducing viral transcription in infected primary CD4 T cells than vorinostat, hexamethylene bisacetamide (HMBA) or mitogenic stimuli [18]. These agents have potential clinical utility in HIV cure trials but adverse events related to immune activation are of potential concern.

Bromodomain inhibitors

Bromodomain and extra-terminal (BET) proteins play a key role in the epigenetic regulation of gene expression by regulating the recruitment of cellular transcription factors [19]. As bromodomain proteins are implicated in cancer [19], BET inhibitors are being investigated for the treatment of multiple malignancies, with 14 BET inhibitors currently in clinical trials. Whereas the initial focus was haematological malignancies such as leukaemia, lymphoma and multiple myeloma, ongoing phase 1/2 trials are evaluating BET inhibitors in a range of solid tumours [20]. The BET proteins BRD2 and BRD4 repress HIV transcription during latency by inhibiting transcriptional initiation or by binding positive transcription elongation factor b (P-TEFb) in resting CD4+ T-cells [19, 21]. Consequently, bromodomain inhibitors are now being explored for their ability to reverse HIV latency. JQ1, i-BET, i-BET151 and MS417 BET inhibitors activated latent HIV in cell lines and some primary CD4+ T-cell latency models, but showed modest or no activity ex vivo in resting CD4+ T-cells from HIV-infected individuals on ART [16, 22, 23]. Moreover, these compounds are not yet in clinical trials in oncology so their associated toxicities in the clinical setting are unknown.

Another BET inhibitor, OTX015, is currently in phase 1 and 1b trials for haematological malignancies and solid tumours including prostate, breast, and lung cancer [24]. OTX015 induced HIV production in resting CD4+ T-cells from HIV-infected individuals on ART [25] and both OTX015 [25] and JQ1 [16, 22] displayed synergy ex vivo when combined with low dose protein kinase C (PKC) agonists. Overall, BET inhibitors clearly have pharmacological potential to activate HIV from latency, which may be enhanced in combination with other LRAs, but the current lack of clinical safety and pharmacokinetic data is likely to limit their immediate development for HIV cure studies.

DNA Methyltransferase Inhibitors

DNA methylation at gene promoters is regulated by DNA methyltransferases (DNMT) leading to transcriptional silencing. These pathways are relevant to myelodysplastic syndromes and malignancies including acute myeloid leukemia [26]. Consequently, DNMT inhibitors have undergone clinical development with 5-azacitidine (azacitidine) and 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (decitabine) now licensed for the treatment of myelodysplastic syndrome and SGI-110 is in a range of clinical trials for various malignancies [26, 27]. Because hypermethylation around the HIV promoter is associated with repression of HIV transcription, DNMT inhibitors are also being investigated for their effect on HIV latency [28]. The DNMT inhibitors decitabine and zebularine activated HIV transcription in latently infected cell lines when combined with other LRAs [29, 30], and decitabine also activated HIV transcription in resting CD4+ T-cells from an aviremic patient on ART with high HIV CpG hypermethylation [29]. However, the overall low frequency of methylation at the HIV promoter in CD4+ T cells from HIV-infected individuals on ART [29] may limit the efficacy of DNMT inhibitors in HIV, and more studies are needed to explore their potential in combination with low doses of tolerable LRAs such as HDACi and disulfiram.

Apoptosis Inducers

Apoptosis, or programmed cell death, eliminates cells that are stressed, damaged or no longer required. Apoptosis is triggered by numerous signals through two main pathways: the extrinsic or intrinsic [31]. The extrinsic pathway is triggered by ligand binding to cell-surface death receptors, whereas the intrinsic pathway is triggered by intracellular stress signals leading to mitochondrial release of cytochrome c, second mitochondria-derived activator of caspase (SMAC) and Omi into the cytosol to trigger apoptosis. Both extrinsic and intrinsic pathways culminate in a proteolytic caspase cascade that induces apoptosis [31]. Apoptosis is regulated by members of the BCL-2 protein family plus inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) proteins including XIAP, cIAP1 and cIAP2 [31, 32]. Inhibitors of apoptosis regulatory proteins, like the anti-apoptotic BCL-2 family of proteins, can trigger cell death and are under clinical development to target malignancies. In HIV cure research, such agents could be exploited to eliminate latently infected cells, avoiding the need for boosting or altering immune-mediated clearance. Combining these inducers of apoptosis with LRAs may potentially lead to selective death of latently infected cells if the apoptotic pathway is triggered by HIV RNA or proteins. Several classes of drugs that induce apoptosis could be relevant to HIV cure, some of which are detailed below.

i. BCL-2 inhibitors

Venetoclax (Venclexta/ABT-199), an oral and highly selective BCL-2 inhibitor, was recently licensed for the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia [33] and was shown to selectively enhance apoptosis of latently infected CD4+ T-cells in vitro following activation with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 [34]. This approach exploited the known interaction between the caspase cleavage peptide Casp8p41, generated by the viral protease, and the cellular protein BAK (which enhances apoptosis) or BCL-2 (which inhibits apoptosis) [34]. Pre-treating T cells from HIV infected individuals on ART ex vivo with venetoclax followed by maximal T cell stimulation induced preferential apoptosis and depleted HIV-infected cells in 8 of 11 patients [34]. Notably, venetoclax did not reduce the viability of CD4+ T-cells in the absence of T cell stimulation. Further investigation of venetoclax using LRAs with less toxicity than maximal T cell stimulation is required to determine if similar synergy is observed. Other inhibitors targeting BCL-2 or other apoptosis regulators (eg. obatoclax/GX15-070 currently in clinical trials) could also be examined to pre-sensitise cells to apoptosis before reactivation of latent HIV.

ii. RIG-I Inducers

Another pathway that can trigger apoptosis is through retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I). RIG-I detects intracellular viral RNA and induces interferon-mediated apoptosis. This pathway can be activated by acitretin, a retinoic acid derivative with activity in non-melanoma skin cancer [35] and approved for the management of severe psoriasis [36]. When acitretin was added to latently infected cell lines or CD4+ T cells from HIV infected individuals on ART, acitretin not only stimulated HIV transcription but also induced RIG-I signalling and the pro-apoptotic BAX protein leading to preferential apoptosis of reactivated cells [37]. Acitretin also stimulated HIV transcription through activation of p300 histone acetyltransferase and this effect was enhanced in the presence of the HDACi vorinostat [37]. This new strategy represents an interesting concept of combining latency reversal with augmented sensing of intracellular viral RNA, potentially enhancing the selective death of virus-producing cells.

iii. IAP Inhibitors – SMAC Mimetics

By antagonising cellular inhibitors of apoptosis proteins (cIAPs), SMAC mimetics promote TNF-mediated cell death and are currently being investigated in numerous phase 1 and phase 2 studies of haematological malignancies and solid tumours [38]. SMAC mimetics may also play a role in cure strategies for HIV although this research is still at an early stage. Depletion of the cIAP BIRC2 by SMAC mimetics induced HIV-expression in cell lines and, when combined with the HDACi panobinostat, had synergistic activity in CD4+ T cells isolated from HIV-infected individuals on ART [39]. The SMAC mimetic birinipant was originally developed for the management of chronic myeloid leukemia, but was recently shown to have no activity in a recent phase 2 study. Birinipant is also in clinical trials for ovarian cancer [40]. In mice infected with hepatitis B virus (HBV), which establishes chronic persistent infection on antiviral therapy, birinipant specifically eliminated HBV infected hepatocytes [41]. More work is required to investigate apoptosis-promoting effects of IAP inhibitors in HIV latency, but it is possible that SMAC mimetics such as birinipant could be useful in targeting latent HIV, particularly given the upregulation of the molecule XIAP in latently infected cells [42].

iv. PI3K/Akt Inhibitors

Dysregulation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) signalling proteins has been implicated in numerous cancers and inhibitors of the key upstream pathway factors, PI3K and Akt, are being explored as potential therapies for targeting a wide range of malignancies including haematological cancers and solid tumours [43]. Inhibiting this pro-survival pathway using PI3K or Akt inhibitors might also promote apoptosis of virus-producing cells but so far there is limited evidence for this effect. The Akt inhibitors miltefosine, perifosine and edelfosine blocked HIV-induced Akt activation and enhanced death of HIV-infected primary human macrophages or a human microglial cell line, [44]. Moreover, arctigenin, lancemaside A1 and compound K, which inhibit different components of the PI3K/Akt pathway, also blocked the pro-survival activity of the HIV protein Tat and increased death of a microglial cell line [45]. These studies demonstrate that PI3K and Akt inhibitors can overcome the pro-survival activities of HIV Tat, but much more work is needed to clarify the potential of these compounds to target latently infected cells and, hence, their future place in cure research remains speculative at present.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors

Upregulation of inhibitory signalling through ICs on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells allows malignant cells to evade immune destruction and, therefore, monoclonal antibodies to block ICs have been developed to enhance anti-tumour immune responses [46]. Monoclonal antibodies against cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4; ipilimumab) and programmed death 1 (PD1; nivolumab and pembrolizumab) were the first to show efficacy in cancer and are now licensed for the treatment of melanoma and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [47, 48]. Furthermore, the use of these antibodies together for melanoma has shown enhanced efficacy, but also increased toxicity [49]. Interestingly, it was recently demonstrated that by modulating T cell chemokine expression, HDACi can enhance the anti-tumour response to anti-PD1 [50]. This concept is currently being tested in a phase 1b/2 clinical trial using the HDACi entinostat in combination with pembrolizumab (anti-PD1) in patients with NSCLC (NCT02437136), and could be highly relevant for the design of future combination studies in HIV cure.

Similar to malignant disease, HIV infection is characterised by increased expression of IC, which is associated with T cell exhaustion and disease progression [51, 52] and may constitute a mechanism for immune escape [53]. Therefore, IC blockade has attracted considerable interest as a strategy to enhance HIV specific T cell responses against virus-expressing cells, supported by previous studies showing that blocking CTLA-4 or PD1 can enhance HIV- and SIV-specific T cell function ex vivo [54, 55]. Furthermore, CD4+ T cells from HIV-infected individuals on ART that express the IC molecule PD1 are highly enriched for integrated HIV DNA and infectious virus in blood [56, 57] and in lymph node follicles [3]. Other IC molecules may also be important for identifying persistent HIV, and this was confirmed by a recent study showing a higher frequency of HIV infection in CD4+ T cells expressing PD1, T cell immunoglobulin and immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif domain (TIGIT) and lymphocyte activation gene 3 (LAG-3) [58]. Collectively, these studies demonstrate that IC expression, in particular PD1, plays a key role in HIV persistence and might also explain why activating T cell function through IC blockade could activate expression of latent HIV, as we recently demonstrated in an HIV infected individual on ART with melanoma who underwent treatment with ipilimumab for malignancy [59].

The only clinical trial thus far to investigate IC blockade in HIV infected individuals on ART without malignancy was a dose-escalation study of BMS-936559, a monoclonal antibody to PD1 ligand1 (PD-L1). Data from the first dose showed an increase in HIV-specific CD8+ T cell responses in two of six individuals treated with a single infusion of low-dose (0.3 mg/kg) anti-PD-L1 but no effect on plasma or cell-associated HIV RNA [60]. Hypophysitis 36 weeks after receiving low-dose anti-PD-L1 was seen in one individual, which raised concern whether the risks of adverse effects with IC blockade could preclude their investigational use in HIV-infected individuals without cancer. Treatment with IC inhibitors can cause a unique spectrum of immune-related adverse events (irAEs) in skin, gut, lung, kidney, liver or the endocrine system [61]. The frequency of irAEs is well described in oncology and rates of grade 3 or 4 irAEs have been relatively low at around 2% in studies with nivolumab or pembrolizumab, although slightly higher for ipilimumab, and considerably higher when ipilimumab and nivolumab were combined [49, 61]. Still, with sufficient monitoring most irAEs are reversible and can be managed fairly easy with glucocorticoids [62]. Notably, no cases of hypophysitis were reported in a phase 1 trial where 207 patients received anti-PD-L1 therapy over 12 weeks [63]. In conclusion, IC blockade represents a highly interesting immune-based intervention in HIV cure research that warrants further investigation. Gathering more robust data on safety and the effect on HIV latency and HIV-specific immunology in infected individuals receiving immunotherapy for management of cancer will be key to advancing this agenda. Two National Cancer Institute (NCI)-sponsored clinical trials, which are currently recruiting study participants, are particularly relevant in this context. These are a phase I dose-escalation study of nivolumab in combination with ipilimumab in patients with HIV-associated solid tumours (NCT02408861), and a phase I study of pembrolizumab in HIV infected individuals with relapsed, refractory or disseminated malignancies (NCT02595866). Both trials have safety as their primary outcome measure but do also investigate effects on HIV latency and the frequency of latently infected cells.

Other strategies that could boost HIV-specific T cell function being explored in cancer and which may be relevant to HIV cure include interleukin (IL)-15 and related agonists [64], IL-21 [65], bi-specific antibodies [66] and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells [67].

Toll-like receptor agonists

Innate immune recognition of foreign pathogens occurs through binding of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMP) to pattern-recognition receptors (PRR) on innate immune cells including the family of toll-like receptors (TLR) [68]. Similarly, during tumour cell death, damage-associated molecular pattern molecules (DAMP) are dispersed, which may also bind to TLR and induce tumour-directed innate immune activation [69]. Consequently, TLR agonists are in development with phase 2 or 3 trials in lung cancer, melanoma, breast cancer and colorectal cancer [70]. In HIV research, TLR agonists have recently attracted attention because they activate antigen-presenting cells (APC) and augment priming of T cells and induce NK cell activation [71, 72]. Most studies have focused on agonists to TLR7 and TLR9, which are both expressed intracellularly on endolysosomes, with TLR7 in plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) and conventional DCs, and TLR9 in pDCs and B cells [73]. Several in vitro studies also suggested that some TLR agonists could activate HIV from latency [74, 75].

MGN1703, a novel TLR9 agonist, induced antiviral innate immune responses and boosted NK cell-mediated viral inhibition in vitro [71]. Based on these findings, MGN1703 is being investigated in a phase 1b/2a trial in 15 ART-suppressed HIV infected individuals, where preliminary data showed that MGN1703 given twice weekly over 4 weeks led to activation of pDCs, NK cells and T cells and an increase in plasma levels of interferon-α [76]. MGN1703 is currently being investigated in phase 3 trials for colorectal cancer [77].

The oral TLR7 agonists, GS-9620 and GS-986 have been administered to ART-suppressed simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-infected rhesus macaques and induced consistent increases in plasma viral RNA and T cell activation [78]. Moreover, two of nine TLR7-treated monkeys had no inducible virus in blood and lymph node tissue and these two animals also displayed virological control for at least 3–4 months when ART was withdrawn [78]. GS-9620 is now in a phase 1 trial in HIV infected individuals on ART.

Conclusion

Translational and clinical research in the HIV cure arena over the past decade has been inspired by drug development in the oncology field. A lot of work has been done to identify new LRAs in addition to HDACi, which have been extensively explored. However, LRAs other than HDACi that have been characterised to date also do not target HIV infected cells specifically. Therefore, significant concerns remain with respect to off target effects, long-term cancer risk and toxicity. Recent advances in cancer immunotherapy has revolutionised the treatment of some malignancies, and it is becoming increasingly clear that improvements in anti-HIV immunity will also be key to achieving ART-free remission. However, the favourable long-term prognosis of someone living with HIV compared to most malignancies means that the risks associated with new interventions need to be assessed with great caution. While we may continue to learn from and apply advances from the oncology field, developing new strategies that specifically target HIV persistence and have an acceptable safety profile remains a top priority.

Key points.

Drugs developed for treating malignancies are being actively investigated as potential therapies to target HIV persistence

Histone deacetylase inhibitors have been employed in clinical trials in HIV infected individuals on ART and activated HIV transcription but on their own, did not reduce the frequency of latently infected CD4+ T cells

Other oncology drug classes are now being explored in vitro and ex vivo for their capacity to augment latency reversal or promote killing of virus-producing cells

Immunomodulation with immune checkpoint inhibitors and toll-like receptor agonists appear to be promising in pre-clinical models of HIV latency and results from clinical trials are eagerly awaited

Acknowledgments

None

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was partly supported by funding from from the American Foundation for AIDS Research, amfAR (grant 109226-58-RGRL); the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia; the National Institutes of Health Delaney AIDS Research Enterprise (DARE) to find a cure collaboratory (U19 AI096109); and the L.E.W. Carty Charitable Fund. S.R.L. is an NHMRC Practitioner Fellow.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

SRL’s institution has received funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia, National Institutes for Health, American Foundation for AIDS Research; Merck, Viiv, Gilead and Tetralogic for investigator initiated research; Merck, Viiv and Gilead for educational activities.

References

- 1.Chun TW, Stuyver L, Mizell SB, et al. Presence of an inducible HIV-1 latent reservoir during highly active antiretroviral therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:13193–13197. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.13193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bruner KM, Hosmane NN, Siliciano RF. Towards an HIV-1 cure: measuring the latent reservoir. Trends Microbiol. 2015;23:192–203. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2015.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3**.Banga R, Procopio FA, Noto A, et al. PD-1 and follicular helper T cells are responsible for persistent HIV-1 transcription in treated aviremic individuals. Nat Med. 2016 doi: 10.1038/nm.4113. By examining CD4+ T cell populations in blood and luymph node tissue, this study identified lymph node PD1+ cells as the major source of replication-comptent and infectious virus in patients on ART for up to 14 years. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Damouche A, Lazure T, Avettand-Fenoel V, et al. Adipose Tissue Is a Neglected Viral Reservoir and an Inflammatory Site during Chronic HIV and SIV Infection. PLoS pathogens. 2015;11:e1005153. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simonetti FR, Sobolewski MD, Fyne E, et al. Clonally expanded CD4+ T cells can produce infectious HIV-1 in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:1883–1888. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1522675113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6*.Lorenzo-Redondo R, Fryer HR, Bedford T, et al. Persistent HIV-1 replication maintains the tissue reservoir during therapy. Nature. 2016 doi: 10.1038/nature16933. Addresses a controversial issue of residual replication on ART. By using a combination of deep sequencing, phylogenetic analyses and mathematical modeling, they present a model to reconcile residual replication on ART (in lymphoid tissue) with absence of emergence of drug resistance. They propose that in sanctuary sites, drug resistant strains are outcompeted by sensitive strains because of their replicative fitness advantage and may spill over into blood. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7*.Rothenberger MK, Keele BF, Wietgrefe SW, et al. Large number of rebounding/founder HIV variants emerge from multifocal infection in lymphatic tissues after treatment interruption. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:E1126–1134. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1414926112. By examining lymph node biopsies taken at time of plasma viral rebound following ART interruption, this study demonstrated a large number of founder/rebound virus consistent with rebound occurring from multiple sites. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fukazawa Y, Lum R, Okoye AA, et al. B cell follicle sanctuary permits persistent productive simian immunodeficiency virus infection in elite controllers. Nat Med. 2015;21:132–139. doi: 10.1038/nm.3781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Archin NM, Liberty AL, Kashuba AD, et al. Administration of vorinostat disrupts HIV-1 latency in patients on antiretroviral therapy. Nature. 2012;487:482–485. doi: 10.1038/nature11286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elliott JH, Wightman F, Solomon A, et al. Activation of HIV Transcription with Short-Course Vorinostat in HIV-Infected Patients on Suppressive Antiretroviral Therapy. PLoS pathogens. 2014;10:e1004473. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rasmussen TA, Tolstrup M, Brinkmann CR, et al. Panobinostat, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, for latent-virus reactivation in HIV-infected patients on suppressive antiretroviral therapy: a phase 1/2, single group, clinical trial. The Lancet HIV. 2014;1:e13–e21. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(14)70014-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sogaard OS, Graversen ME, Leth S, et al. The Depsipeptide Romidepsin Reverses HIV-1 Latency In Vivo. PLoS pathogens. 2015;11:e1005142. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leth S, Schleimann MH, Nissen SK et al.

- 14.Kulkosky J, Culnan DM, Roman J, et al. Prostratin: activation of latent HIV-1 expression suggests a potential inductive adjuvant therapy for HAART. Blood. 2001;98:3006–3015. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.10.3006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Plimack ER, Tan T, Wong YN, et al. A phase I study of temsirolimus and bryostatin-1 in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma and soft tissue sarcoma. Oncologist. 2014;19:354–355. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16*.Laird GM, Bullen CK, Rosenbloom DI, et al. Ex vivo analysis identifies effective HIV-1 latency-reversing drug combinations. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2015;125:1901–1912. doi: 10.1172/JCI80142. Unveils synergistic LRAs (PKC agonist and HDACi or JQ1 BET inhibitor) that robustly reactive latent HIV in resting CD4 T-cells from patients on ART, expanding options for clinical development. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17*.Gutierrez C, Serrano-Villar S, Madrid-Elena N, et al. Bryostatin-1 for latent virus reactivation in HIV-infected patients on antiretroviral therapy. Aids. 2016;30:1385–1392. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001064. The first clinical study to investigate bryostatin-1 in HIV patients but was unable to demonstrate any effect on HIV transcription or PKC activity with the used doses. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pandelo Jose D, Bartholomeeusen K, da Cunha RD, et al. Reactivation of latent HIV-1 by new semi-synthetic ingenol esters. Virology. 2014;462–463:328–339. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2014.05.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Filippakopoulos P, Knapp S. Targeting bromodomains: epigenetic readers of lysine acetylation. Nature reviews. Drug discovery. 2014;13:337–356. doi: 10.1038/nrd4286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sahai V, Redig AJ, Collier KA, et al. Targeting bet bromodomain proteins in solid tumors. Oncotarget. 2016 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jeng MY, Ali I, Ott M. Manipulation of the host protein acetylation network by human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Critical reviews in biochemistry and molecular biology. 2015;50:314–325. doi: 10.3109/10409238.2015.1061973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22*.Darcis G, Kula A, Bouchat S, et al. An In-Depth Comparison of Latency-Reversing Agent Combinations in Various In Vitro and Ex Vivo HIV-1 Latency Models Identified Bryostatin-1+JQ1 and Ingenol-B+JQ1 to Potently Reactivate Viral Gene Expression. PLoS pathogens. 2015;11:e1005063. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005063. Identifies synergistic LRAs (PKC agonists and JQ1 BET inhibitor) that potently reactive latent HIV in resting CD4 T-cells from patients on ART, and thus of great interest for clinical development. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boehm D, Calvanese V, Dar RD, et al. BET bromodomain-targeting compounds reactivate HIV from latency via a Tat-independent mechanism. Cell Cycle. 2013;12:452–462. doi: 10.4161/cc.23309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Theodoulou NH, Tomkinson NC, Prinjha RK, Humphreys PG. Clinical progress and pharmacology of small molecule bromodomain inhibitors. Current opinion in chemical biology. 2016;33:58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2016.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *25.Lu P, Qu X, Shen Y, et al. The BET inhibitor OTX015 reactivates latent HIV-1 through P-TEFb. Scientific reports. 2016;6:24100. doi: 10.1038/srep24100. Recent report of a novel, oral BET inhibitor in cancer clinical trials that also reactivates replication-competent virus in CD4 T-cells from HIV patients on ART and thus is promising for further development. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fratta E, Montico B, Rizzo A, et al. Epimutational profile of hematologic malignancies as attractive target for new epigenetic therapies. Oncotarget. 2016 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nebbioso A, Carafa V, Benedetti R, Altucci L. Trials with ‘epigenetic’ drugs: an update. Molecular oncology. 2012;6:657–682. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kauder SE, Bosque A, Lindqvist A, et al. Epigenetic regulation of HIV-1 latency by cytosine methylation. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000495. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blazkova J, Trejbalova K, Gondois-Rey F, et al. CpG methylation controls reactivation of HIV from latency. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000554. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fernandez G, Zeichner SL. Cell line-dependent variability in HIV activation employing DNMT inhibitors. Virology journal. 2010;7:266. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-7-266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Green DR, Llambi F. Cell Death Signaling. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology. 2015:7. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Estornes Y, Bertrand MJ. IAPs, regulators of innate immunity and inflammation. Seminars in cell & developmental biology. 2015;39:106–114. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roberts AW, Davids MS, Pagel JM, et al. Targeting BCL2 with Venetoclax in Relapsed Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:311–322. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1513257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34**.Cummins NW, Sainski AM, Dai H, et al. Prime, Shock, and Kill: Priming CD4 T Cells from HIV Patients with a BCL-2 Antagonist before HIV Reactivation Reduces HIV Reservoir Size. Journal of virology. 2016;90:4032–4048. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03179-15. Identifies a new, FDA-approved, oral BCL-2 inhibitor that selectively depletes reactivated resting CD4 T-cells from HIV patients on ART. This is promising for combining with LRAs less toxic than maximal T-cell stimulation to selectively purge the latent HIV reservoir in resting CD4 T-cells. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prado R, Francis SO, Mason MN, et al. Nonmelanoma skin cancer chemoprevention. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al] 2011;37:1566–1578. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.02108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dunn LK, Gaar LR, Yentzer BA, et al. Acitretin in dermatology: a review. Journal of drugs in dermatology : JDD. 2011;10:772–782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37**.Li P, Kaiser P, Lampiris HW, et al. Stimulating the RIG-I pathway to kill cells in the latent HIV reservoir following viral reactivation. Nature medicine. 2016 doi: 10.1038/nm.4124. Identifies an FDA-approved compound, acitretin, that both reactivates latent HIV and induces RIG-I signalling for selective apoptosis of reactivated latently-infected cells from HIV patients on ART. It is promising for development alone or with other LRAs to selectively purge the latent HIV reservoir. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bai L, Smith DC, Wang S. Small-molecule SMAC mimetics as new cancer therapeutics. Pharmacol Ther. 2014;144:82–95. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2014.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pache L, Dutra MS, Spivak AM, et al. BIRC2/cIAP1 Is a Negative Regulator of HIV-1 Transcription and Can Be Targeted by Smac Mimetics to Promote Reversal of Viral Latency. Cell host & microbe. 2015;18:345–353. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Noonan AM, Bunch KP, Chen JQ, et al. Pharmacodynamic markers and clinical results from the phase 2 study of the SMAC mimetic birinapant in women with relapsed platinum-resistant or -refractory epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer. 2016;122:588–597. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ebert G, Allison C, Preston S, et al. Eliminating hepatitis B by antagonizing cellular inhibitors of apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:5803–5808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1502400112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Berro R, de la Fuente C, Klase Z, et al. Identifying the membrane proteome of HIV-1 latently infected cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282:8207–8218. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606324200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mundi PS, Sachdev J, McCourt C, Kalinsky K. AKT in cancer: new molecular insights and advances in drug development. British journal of clinical pharmacology. 2016 doi: 10.1111/bcp.13021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lucas A, Kim Y, Rivera-Pabon O, et al. Targeting the PI3K/Akt cell survival pathway to induce cell death of HIV-1 infected macrophages with alkylphospholipid compounds. PloS one. 2010:5. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim Y, Hollenbaugh JA, Kim DH, Kim B. Novel PI3K/Akt inhibitors screened by the cytoprotective function of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat. PloS one. 2011;6:e21781. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sharma P, Allison JP. Immune checkpoint targeting in cancer therapy: toward combination strategies with curative potential. Cell. 2015;161:205–214. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weber JS, D’Angelo SP, Minor D, et al. Nivolumab versus chemotherapy in patients with advanced melanoma who progressed after anti-CTLA-4 treatment (CheckMate 037): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:375–384. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Robert C, Schachter J, Long GV, et al. Pembrolizumab versus Ipilimumab in Advanced Melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2521–2532. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1503093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Postow MA, Chesney J, Pavlick AC, et al. Nivolumab and ipilimumab versus ipilimumab in untreated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2006–2017. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50**.Zheng H, Zhao W, Yan C. HDAC Inhibitors Enhance T-Cell Chemokine Expression and Augment Response to PD-1 Immunotherapy in Lung Adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2016 doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2584. This study identified histone deacetylase inhibitors as being capable of augmenting the anti-tumour response to PD1 blockade and confirmed this effect of combination treatment in vivo in multiple models of lung tumours. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Day CL, Kaufmann DE, Kiepiela P, et al. PD-1 expression on HIV-specific T cells is associated with T-cell exhaustion and disease progression. Nature. 2006;443:350–354. doi: 10.1038/nature05115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chew GM, Fujita T, Webb GM, et al. TIGIT Marks Exhausted T Cells, Correlates with Disease Progression, and Serves as a Target for Immune Restoration in HIV and SIV Infection. PLoS pathogens. 2016;12:e1005349. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Akhmetzyanova I, Drabczyk M, Neff CP, et al. Correction: PD-L1 Expression on Retrovirus-Infected Cells Mediates Immune Escape from CD8+ T Cell Killing. PLoS pathogens. 2015;11:e1005364. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Porichis F, Kwon DS, Zupkosky J, et al. Responsiveness of HIV-specific CD4 T cells to PD-1 blockade. Blood. 2011;118:965–974. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-328070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Velu V, Titanji K, Zhu B, et al. Enhancing SIV-specific immunity in vivo by PD-1 blockade. Nature. 2009;458:206–210. doi: 10.1038/nature07662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chomont N, El-Far M, Ancuta P, et al. HIV reservoir size and persistence are driven by T cell survival and homeostatic proliferation. Nat Med. 2009;15:893–900. doi: 10.1038/nm.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pallikkuth S, Sharkey M, Babic DZ, et al. Peripheral T Follicular Helper Cells Are the Major HIV Reservoir within Central Memory CD4 T Cells in Peripheral Blood from Chronically HIV-Infected Individuals on Combination Antiretroviral Therapy. J Virol. 2015;90:2718–2728. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02883-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58*.Fromentin R, Bakeman W, Lawani MB, et al. CD4+ T Cells Expressing PD-1, TIGIT and LAG-3 Contribute to HIV Persistence during ART. PLoS pathogens. 2016;12:e1005761. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005761. This study explored the association between expression of immune checkpoint molecules and HIV persistence and demonstrated that expression of PD1, TIGIT and LAG-3 identifies CD4+ T cells with higher levels of HIV DNA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wightman F, Solomon A, Kumar SS, et al. Effect of ipilimumab on the HIV reservoir in an HIV-infected individual with metastatic melanoma. AIDS. 2015;29:504–506. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Eron J, Gay C, Bosch R, et al. Safety, Immunologic and Virologic Activity of Anti-PD-L1 in HIV-1 Participants on ART. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Boston, MA. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Eigentler TK, Hassel JC, Berking C, et al. Diagnosis, monitoring and management of immune-related adverse drug reactions of anti-PD-1 antibody therapy. Cancer Treat Rev. 2016;45:7–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2016.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Spain L, Diem S, Larkin J. Management of toxicities of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Cancer Treat Rev. 2016;44:51–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brahmer JR, Tykodi SS, Chow LQ, et al. Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2455–2465. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jones RB. Cytotoxic T-Lymphocytes in Combination with the IL-15 Superagonist ALT-803 Eliminate Latently HIV-Infected Autologous CD4+ T-Cells from Natural Reservoirs. Keystone Symposium, Mechanisms of HIV Persistence: Implications for a Cure; Boston, USA. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 65*.Micci L, Ryan ES, Fromentin R, et al. Interleukin-21 combined with ART reduces inflammation and viral reservoir in SIV-infected macaques. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2015;125:4497–4513. doi: 10.1172/JCI81400. Treatment of ART-treated SIV-infected macaques with IL-21 led to improved restoration of intestinal Th17 and Th22 cells and a more effective reduction of immune activation compared with ART alone. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66*.Sung JA, Pickeral J, Liu L, et al. Dual-Affinity Re-Targeting proteins direct T cell-mediated cytolysis of latently HIV-infected cells. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2015 doi: 10.1172/JCI82314. In this study it was shown that bi-specific antibodies that target both envelope and CD3 mediated CD8+ T cell clearance of CD4+ T cells obtained from HIV infected individuals on ART following induction of HIV-expression. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Leibman RS, Riley JL. Engineering T Cells to Functionally Cure HIV-1 Infection. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2015;23:1149–1159. doi: 10.1038/mt.2015.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kanzler H, Barrat FJ, Hessel EM, Coffman RL. Therapeutic targeting of innate immunity with Toll-like receptor agonists and antagonists. Nat Med. 2007;13:552–559. doi: 10.1038/nm1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Liu Y, Zeng G. Cancer and innate immune system interactions: translational potentials for cancer immunotherapy. J Immunother. 2012;35:299–308. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3182518e83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Krieg AM. Development of TLR9 agonists for cancer therapy. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2007;117:1184–1194. doi: 10.1172/JCI31414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Offersen R, Nissen SK, Rasmussen TA, et al. A Novel Toll-Like Receptor 9 Agonist, MGN1703, Enhances HIV-1 Transcription and NK Cell-Mediated Inhibition of HIV-1-Infected Autologous CD4+ T Cells. J Virol. 2016;90:4441–4453. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00222-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Buitendijk M, Eszterhas SK, Howell AL. Toll-like receptor agonists are potent inhibitors of human immunodeficiency virus-type 1 replication in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2014;30:457–467. doi: 10.1089/AID.2013.0199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kawai T, Akira S. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on Toll-like receptors. Nature immunology. 2010;11:373–384. doi: 10.1038/ni.1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Scheller C, Ullrich A, Lamla S, et al. Dual activity of phosphorothioate CpG oligodeoxynucleotides on HIV: reactivation of latent provirus and inhibition of productive infection in human T cells. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2006;1091:540–547. doi: 10.1196/annals.1378.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Scheller C, Ullrich A, McPherson K, et al. CpG oligodeoxynucleotides activate HIV replication in latently infected human T cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:21897–21902. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311609200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vibholm L, Schleimann MH, Offersen R, et al. TLR9 agonist MGN1703 treatment enhances cellular immune responses in HIV infected individuals on ART. HIV Persistence: Pathogenesis and Eradication (Keystone Symposium X7); Olympic Valley, CA. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schmoll HJ, Wittig B, Arnold D, et al. Maintenance treatment with the immunomodulator MGN1703, a Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9) agonist, in patients with metastatic colorectal carcinoma and disease control after chemotherapy: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2014;140:1615–1624. doi: 10.1007/s00432-014-1682-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Whitney JB, Lim SY, Osuna C, et al. Repeated TLR7 Agonist Treatment of SIV+ Monkeys on ART Can Lead to Viral Remission. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Boston, MA. 2016. [Google Scholar]