Abstract

Although it is established that the composition of the human intestinal microbiota changes with age, transition of the intestinal microbiota of animals with age has not been well studied. In the present study, we collected fresh fecal samples from dogs of 5 different age groups (pre-weanling, weanling, young, aged, senile) and analyzed the compositions of their intestinal microbiota with a culture-based method. The results suggested that the composition of the canine intestinal microbiota also changes with age. Among intestinal bacteria predominant in dog intestines, lactobacilli appeared to change with age. Both the number and the prevalence of lactobacilli tended to decrease when dogs became older. Bifidobacteria, on the other hand, was not predominant in the intestine of the dogs. We also identified lactobacilli at the species level based on 16S rRNA gene sequences and found that the species composition of Lactobacillus also changed with age. It was further suggested that bacteria species beneficial to host animals may differ depending on the host species.

Keywords: aging, bifidobacteria, dog, intestinal microbiota, lactobacilli

INTRODUCTION

It is now well established that the intestinal microbiota confers such great impacts on host health such as in development of normal immune systems, prevention of metabolic diseases, and alleviation of the course of infectious diseases to name a few. Maintaining an optimal intestinal microbiota is indispensable for good health of the host. Among the many factors that influence the composition of the intestinal microbiota, age is one of the most critical [1, 2]. It has been reported that the composition of the human intestinal microbiota changes with age, and “aging of the intestinal microbiota” is thought to be somehow related to the health of the host [1, 2]. For example, it was revealed that bifidobacteria, which are thought to be a beneficial bacterial group, decreases during the transition from middle age to old age, while the numbers of Clostridium perfringens, lactobacilli, enterococci and Enterobacteriaceae increase [1, 2].

The dog is one of the most popular companion animals around the world and is beginning to play important roles as a member of the family. Recent advances of veterinary practices have dramatically prolonged the life span of dogs, leading to unprecedented ballooning of the aged dog population. Beside disorders associated with longevity, the aged dog population is likely to be more vulnerable to infectious diseases, leading to increased opportunity for administration of antimicrobials. There are growing concerns regarding the emergence of antimicrobial resistant bacteria, and the World Health Organization recently indicated in its Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance that urgent responses are seriously needed to face this problem [3]. Prudent use of antimicrobials is required in both human and veterinary medical practices. Probiotics are expected to be alternative intervention measures to prevent bacterial infections in aged dogs. To identify probiotic bacteria beneficial to the health of aged dogs, better understanding of the aging of the intestinal microbiota is important. If such beneficial probiotics become available, they would contribute to the improvement of quality of life (QOL) of both dogs and their owners. Although the compositions of the intestinal microbiota of various animal species have been studied, transition of the intestinal microbiota of animals with age, including that in dogs, has not been well studied [1, 2, 4, 5].

In this study, we analyzed the composition of the intestinal microbiota in dogs of different age groups to elucidate the age-dependent transitions and attempted to isolate and identify bacteria potentially beneficial to aged dog health status.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

In this study, we collected fresh fecal samples from 5 different age groups of dogs, and each group contained 10 animals (Table 1). Animals in pre-weanling and weanling groups were 11 to 15 days old and 6 to 7 weeks old respectively. Young dogs were 2 years old, and aged dogs were 10 to 13 years old. These dogs were beagles bred and maintained at Kitayama Labes Co., Ltd. (Nagano, Japan). Pre-weanling dogs were breast-fed, while weanling, young and aged dogs were reared individually and fed DS-E diet (Oriental Yeast Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Senile dogs were 16 to 17 years old. They were of various breeds and kept in ordinary households without special food restrictions.

Table 1. Dogs used in this study.

| Group | n | Age | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-weanling | 10 | 13.2 ± 1.8 | days |

| Weanling | 10 | 6.8 ± 0.4 | weeks |

| Young | 10 | 2.0 ± 0.0 | years |

| Aged | 10 | 11.5 ± 0.9 | years |

| Senile | 10 | 16.7 ± 0.5 | years |

Collection of fecal samples

Fresh fecal samples were collected after defecation and kept under anaerobic conditions with AnaeroPack® Kenki (Mitsubishi Gas Chemical Company Inc., Tokyo, Japan). In the case of the pre-weanling group, puppies were provoked to defecate. Samples were refrigerated and transported to Laboratory of Veterinary Public Health, the University of Tokyo, the next day.

Bacteriological procedures

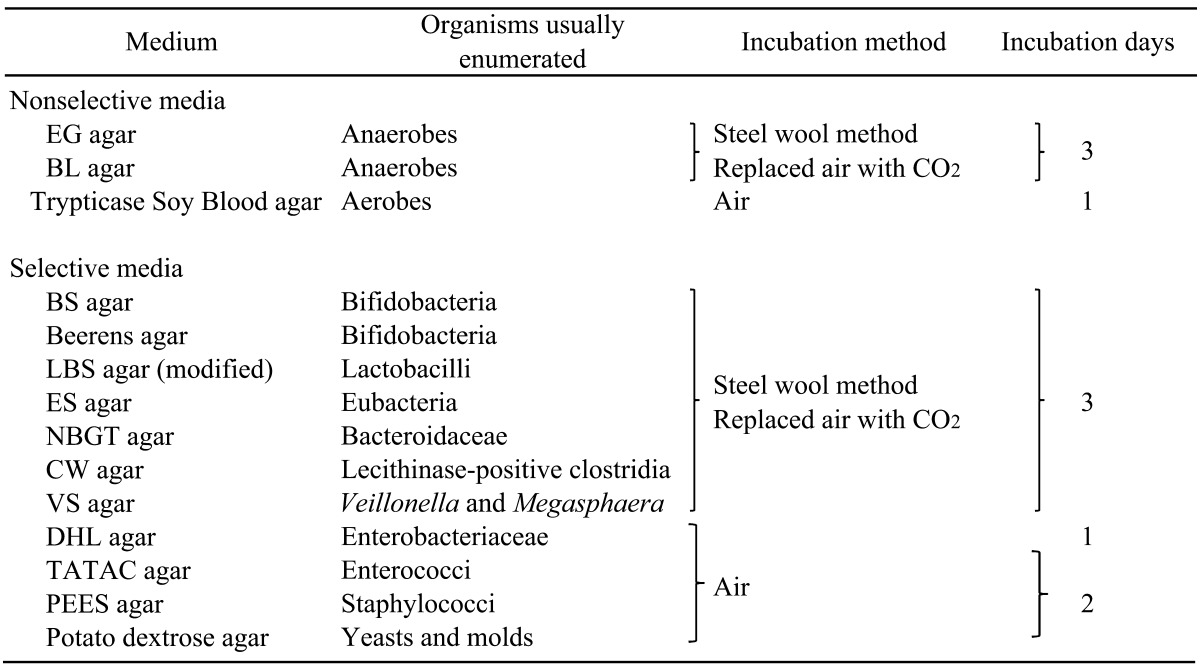

Bacteriological procedures were essentially the same as those described previously [1, 2, 6]. Samples were weighed and introduced into an anaerobic chamber (85% N2, 5% CO2, and 10% H2), and 10-fold serial dilutions were prepared with prereduced trypticase soy broth without dextrose (BBL, Sparks, MD, USA) supplemented with 0.5 g of agar, 0.84 g of Na2CO3 and 0.5 g of L-cysteine•HCl•H2O (pH 7.2). Dilutions were then inoculated onto 3 nonselective and 8 selective agar media (Table 2). Beerens agar medium [7] was also included for isolation of bifidobacteria. Bacteria were identified at the levels of genus or family based on colony form, Gram staining, cell morphology, and growth under aerobic conditions. Bacterial numbers were expressed as the log10 number of bacteria per gram wet weight of feces. Based on the colony and cell morphology, 1 to 3 colonies of bifidobacteria and lactobacilli per sample were isolated from modified LBS, BS, and Beerens agar and stored at −80°C for further identification.

Table 2. The media and cultural method for comprehensive investigation of intestinal microbiota.

Species identification of isolates

The DNA of isolated bacteria was extracted using a Simple Prep® DNA Extraction Kit (Takara Bio Inc., Kusatsu, Shiga, Japan), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The 16S rRNA gene was amplified from the DNA extracts using a Bacterial 16S rDNA PCR Kit (Takara Bio), and the PCR products were purified with NucleoSpin® Gel and PCR Clean-up (Macherey-Nagel GmbH & Co. KG., Düren, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The sequences of the purified products were analyzed by FASMAC Co., Ltd. sequencing service (Kanagawa, Japan). The sequences obtained were compared with those available in nucleic acid databases using the EzTaxon-e database (http://www.eztaxon-e.ezbiocloud.net/) [8] and species were identified as the top hit species with <98% similarity using the EzTaxon-e database.

Statistical analysis

Bacterial numbers were compared among 5 groups by Tukey’s t-test. Detection frequencies were compared by Fisher’s exact tests. All statistical analyses were performed using EZR (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan), which is a graphical user interface for R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) [9].

RESULTS

The composition of the intestinal microbiota of dogs in different age groups

The compositions of the fecal microbiota in different age groups are shown in Table 3. Lactobacilli were detected in all animals from the pre-weanling, weanling, young and aged groups, while only 30% of dogs in senile group tested positive for lactobacilli. The prevalence of lactobacilli in the senile group was, therefore, significantly lower compared with those in the four other groups. The mean number of lactobacilli was also significantly lower in the aged group than those in the pre-weanling group. Bifidobacteria were detected in 5 out of 10 pre-weanling puppies and 6 out of 10 weanling puppies but were not detected in the dogs of the three other elder age groups. Although clostridia were not found in weanling dogs, many dogs in the four other groups harbored this bacterial group.

Table 3. Fecal microbiota of the different age groups of dogs.

| Bacterial groups | Pre-weanling (n=10) | Weanling (n=10) | Young (n=10) | Aged (n=10) | Senile (n=10) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteroidaceae | 10.4 ± 0.6a | (10) | 10.4 ± 0.4b | (10) | 9.7 ± 0.3a,b | (10) | 10.0 ± 0.5 | (10) | 10.0 ± 0.4 | (10) |

| bifidobacteria | 9.5 ± 0.6 | (5)a,b,c | 9.7 ± 0.7 | (6)d,e,f | (0)a,d | (0)b,e | (0)c,f | |||

| eubacteria | 9.3 ± 1.1a | (9) | 10.4 ± 0.6a,b | (10) | 9.4 ± 0.3b | (10) | 9.5 ± 0.8 | (10) | 9.7 ± 0.2 | (9) |

| clostridia | 8.0 ± 1.5 | (6)a | (0)a,b,c,d | 8.9 ± 1.0 | (10)b | 8.7 ± 1.0 | (9)c | 8.6 ± 0.6 | (8)d | |

| Veillonella | 4.4 ± 2.0 | (4) | 3.7 ± 0.9 | (2) | ||||||

| Megasphaera | 7.5 | (1) | 4.6 ± 1.7 | (2) | 6.6 | (1) | (0) | |||

| lactobacilli | 9.7 ± 0.6a | (10)a | 8.7 ± 1.4 | (10)b | 9.5 ± 0.7 | (10)c | 8.2 ± 1.3a | (10)d | 8.5 ± 2.4 | (3)a,b,c,d |

| Enterobacteriaceae | 9.4 ± 1.0a,b | (10) | 8.2 ± 1.5 | (10) | 7.5 ± 0.9a | (10) | 7.1 ± 2.2b,c | (10) | 8.9 ± 0.9c | (10) |

| enterococci | 9.8 ± 0.6 | (10) | 9.0 ± 1.1 | (10) | 9.2 ± 0.5 | (10) | 8.9 ± 1.3 | (10) | 8.7 ± 1.4 | (10) |

| staphylococci | (0)a,b | (0)c,d | 3.3 ± 0.6 | (8)a,c,e | (0)e,f | 4.6 ± 1.4 | (9)b,d,f | |||

| total count | 10.8 ± 0.4a | 10.8 ± 0.4b | 10.3 ± 0.2a,b | 10.4 ± 0.4 | 10.4 ± 0.3 | |||||

Mean ± SD of log10/g feces when the organism was present (number of subjects in which the organism was detected).

a–f The same superscript letters in the same horizontal line indicate significant differences (p<0.05).

The number of enterobacteriaceae was significantly lower in young and aged dogs compared with pre-weanling dogs, and significantly higher numbers of enterobacteriaceae were detected in dogs of the senile group compared with those of the aged group. Compared with pre-weanling and weanling dogs, the number of bacteroidaceae was significantly low in young dogs. The highest number of eubacteria was detected in feces of weanling dogs.

Species identification of lactobacilli

Since the prevalence as well as the number of lactobacilli appeared to decrease in an age-dependent manner, isolated strains of lactobacilli were subjected to nucleotide sequencing of the 16S rRNA genes to delineate them at the species level (Table 4).

Table 4. Occurrence of species of lactobacilli in feces of dogs in the different age groups.

| Species | Pre-weanling | Weanling | Young | Aged | Senile |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. animalis | 7 | 4 | 8 | 9 | 0 |

| L. johnsonii | 8 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| L. gallinarum | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| L. paracasei subsp. paracasei | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| L. reuteri | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| L. ruminis | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

In pre-weanling group, only Lactobacillus animalis and Lactobacillus johnsonii were detected. L. johnsonii was mostly isolated from pre-weanling dogs, while L. animalis strains were isolated from dogs of almost all age groups except the senile group. In the young and aged groups, L. animalis was the predominant species. Three out of ten senile dogs were found to harbor Lactobacillus gallinarum, Lactobacillus paracasei subsp. paracasei, and Lactobacillus reuteri, respectively.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we analyzed the composition of the intestinal microbiota of dogs in different age groups. Although we did not follow up the same cohort of animals for prolonged years, our results seem to suggest aging of the intestinal microbiota in dogs. Among the predominant microbes at younger ages as represented by the pre-weanling and young groups, not only the prevalence but also the number of lactobacilli and enterococci appeared to decrease as the animals got older. A slight decrease in the prevalence of eubacteria was also noted after the weanling stage, while bacteroidaceae was the most predominant throughout life. These results basically agree with the previous finding indicating that lactobacilli were the predominant species in younger animals but that the numbers of eubacteria in elderly animals was lower in comparison with younger dogs [10].

Among the pre-weanling, weanling, and young groups, there were significant differences in the numbers of bacteroidaceae, eubacteria, and enterobacteriaceae and the incidence of bifidobacteria, clostridia, and staphylococci. Although the influence of other environmental factors cannot be ruled out, the weanling stage seems to have a great impact on the composition of the intestinal microbiota of dogs.

The present study employed a culture-based method, which was essentially the same as that described by Mitsuoka et al. [1, 2, 6], to analyze the composition of the intestinal microbiota of dogs, because we aimed to not only identify beneficial age-related changes in the composition of the canine intestinal microbiota but also to isolate particular bacteria for future development of probiotics targeting dogs. Recent advances in the molecular methods for studies on the microbiota have made quick and more comprehensive analysis of the intestinal microbiota possible. A previous study utilizing a molecular method reported that the composition of the microbiota of six healthy 1.7-year-old dogs comprised about 35% each of phyla Bacteroidetes/Chlorobi group and Firmicutes, followed by Proteobacteria (13–15%) and Fusobacteria (7–8%) [11]. Most of the bacteria classified in bacteroidaceae in this study belong to the phyla Bacteroidetes and Fusobacteria, while lactobacilli, enterococci, clostridia, and eubacteria belong to phylum Firmicutes. Furthermore, bacteria identified as enterobacteriaceae in this study belong to phylum Proteobacteria, indicating that the results obtained by the culture method well coincided with the previous findings obtained by using molecular techniques.

It has been reported that the composition of the intestinal microbiota of human beings changes with age. The dominance of bifidobacteria observed in infancy is not evident in the middle-aged population, and there are slight reductions in total bacterial counts. Furthermore, bifidobacteria become completely undetectable in some individuals in old age. On the other hand, the prevalence rates and numbers of Clostridium perfringens, Lactobacillus, Enterobacteriaceae, and Enterococcus markedly increase [4]. Although bifidobacteria are the most predominant bacteria in infants and one of the predominant bacteria in adults in humans [12] and are thought to confer some health benefits, bifidobacteria were isolated only from about half of the pre-weanling and weanling dogs and from none of the aged dogs, suggesting that bifidobacteria may not play important roles in dogs in contrast to humans. On the other hand, lactobacilli were one of the predominant bacteria in younger dogs. The number and prevalence of lactobacilli appeared to decrease in senile individuals, in contrast to the finding in humans indicating that the prevalence and numbers of lactobacilli in the human gut increased with age [13, 14]. It seems, therefore, likely that lactobacilli may exert some health benefits in dogs similar to those anticipated for bifidobacteria in humans. We also observed a significant decrease of enterobacteriaceae after the weanling stage and a subsequent increase in senile dogs. The roles played by each component bacterium in the microbiota might be different depending on the species of animals in question.

Our results suggested that Bifidobacterium species are not as important for dog health as in the case of humans. Instead, we found that a transition with age did occur in lactobacilli in dogs, suggesting the possible importance of this bacterial group for dog health. In addition, at the species level, L. animalis and L. johnsonii were the most common species among the isolates from the pre-weanling dogs, while various species of Lactobacillus were isolated from the elder dogs. In contrast to L. animalis, which was isolated from all age groups except for the senile group, L. johnsonii strains were mostly isolated from pre-weanling dogs, suggesting that L. johnsonii might be a specific species for infant dogs but that L. animalis can colonize in dogs of all ages. Considering that some major human probiotic species are predominant species in healthy infants and decrease in elder individuals [15, 16] and that L. johnsonii strains have potential for use in developing probiotic food [17], the L. johnsonii isolated in this study might also have the potential to be probiotics specifically for dogs. In addition, the Lactobacillus species detected from senile dogs were drastically different from those of the other age groups. L. gallinarum and L. paracasei subsp. paracasei were isolated only from senile dogs. However, because these senile dogs were of various breeds and kept in ordinary households, further studies with senile dogs under well-controlled conditions should be performed.

The present study suggested that the intestinal microbiota of dogs might undergo age-dependent changes at the levels of both bacterial groups and species, as in the case of the human intestinal microbiota, and that the roles played by some intestinal bacterial groups of dogs might be different from those of humans. Lactobacilli were suggested to be the major bacteria playing important roles to control intestinal conditions of dogs. Bifidobacteria, which are one of the predominant bacterial groups in humans and thought to play important roles in human health, were not dominant in the dog intestine, especially for older age groups. The results of the present study indicate the importance of development of probiotics specific to dogs.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mitsuoka T, Hayakawa K. 1973. Die Faekal Flora bei Menschen I. Die Zusammensetzung der Faekalflora der verschiedenen Altersgruppen. Zbl Bakt Hyg I Orig 233: 333–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitsuoka T, Hayakawa K, Kimura N. 1974. Die Faekal Flora bei Menschen II. Die Zusammensetzung der Bifiobacterienflora der verschiedenen Altersgruppen. Zbl Bakt Hyg I Orig 226: 469–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. 2014. Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/94384/1/9789241506236_eng.pdf.

- 4.Smith HW. 1965. The development of the flora of the alimentary tract in young animals. J Pathol Bacteriol 90: 495–513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitsuoka T, Kaneuchi C. 1977. Ecology of the bifidobacteria. Am J Clin Nutr 30: 1799–1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirayama K, Itoh K, Takahashi E, Mitsuoka T. 1995. Comparison of composition of faecal microbiota and metabolism of faecal bacteria among ‘human-flora-associated’ mice inoculated with faeces from six different human donors. Microb Ecol Health Dis 8: 199–211. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beerens H. 1990. An elective and selective isolation medium for Bifidobacterium spp. Lett Appl Microbiol 11: 155–157. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim OS, Cho YJ, Lee K, Yoon SH, Kim M, Na H, Park SC, Jeon YS, Lee JH, Yi H, Won S, Chun J. 2012. Introducing EzTaxon-e: a prokaryotic 16S rRNA gene sequence database with phylotypes that represent uncultured species. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 62: 716–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kanda Y. 2013. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant 48: 452–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benno Y, Nakao H, Uchida K, Mitsuoka T. 1992. Impact of the advances in age on the gastrointestinal microflora of beagle dogs. J Vet Med Sci 54: 703–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Swanson KS, Dowd SE, Suchodolski JS, Middelbos IS, Vester BM, Barry KA, Nelson KE, Torralba M, Henrissat B, Coutinho PM, Cann IKO, White BA, Fahey GC., Jr2011. Phylogenetic and gene-centric metagenomics of the canine intestinal microbiome reveals similarities with humans and mice. ISME J 5: 639–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitsuoka T.2011. History and evolution of probiotics. Jpn J Lactic Acid Bact 22: 26–37. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitsuoka T. 2011. The progress of intestinal microbiota research. Biosci Microflora 25: 113–124. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitsuoka T. 1992. Intestinal flora and aging. Nutr Rev 50: 438–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maldonado J, Cañabate F, Sempere L, Vela F, Sánchez AR, Narbona E, López-Huertas E, Geerlings A, Valero AD, Olivares M, Lara-Villoslada F. 2012. Human milk probiotic Lactobacillus fermentum CECT5716 reduces the incidence of gastrointestinal and upper respiratory tract infections in infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 54: 55–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ménard O, Butel MJ, Gaboriau-Routhiau V, Waligora-Dupriet AJ. 2008. Gnotobiotic mouse immune response induced by Bifidobacterium sp. strains isolated from infants. Appl Environ Microbiol 74: 660–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zielińska D, Rzepkowska A, Radawska A, Zieliński K. 2015. In vitro screening of selected probiotic properties of Lactobacillus strains isolated from traditional fermented cabbage and cucumber. Curr Microbiol 70: 183–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]