Abstract

Background:

During recent decades, various factors have modified the nurse–physician professional relationship pattern in hospital settings. The present study investigates the typology and dynamics of this relationship as well as the effects of social structures and the actors’ agency by considering the gender variable in two professional groups of nurse and physician.

Materials and Methods:

A survey was conducted in 2009 using a quota sampling method of 100 female nurses and male physicians in four hospitals in Tehran.

Results:

The study revealed three distinct patterns of nurse–physician professional relationship including “dependence–independence,” “nondominance–dominance,” and “cooperation–participation.” Occupational socialization, gender stereotypes, organization support, and actors’ agency were discovered as the most effective factors.

Conclusions:

Observing caution in generalizing the results, the predominant relationship pattern was derived from the persistence of gender stereotypes in the occupational context. Although there is a paradigm shift in the relational and embodied structures, balancing power resources are being formed by younger nurses who require more organizational support to improve the professional fulfilment and authority.

Keywords: Gender, Iran, nurse and physician, professional power

Introduction

While both patients and professionals benefit from a strong professional alliance,[1] evidence shows that a conflict between physician and nurse continuously leads to negative outcomes in health services.[2,3] Studies have illustrated that nurses’ autonomy and professional fulfilment are strongly influenced by their interactions with physicians.[4,5,6,7] Historically, nursing is viewed as a women's job.[8] While the American nurses’ gender ratio (male:female) is reported to be 1:9.5,[8] the percentage of women's entry to American medical schools has increased only from 26% to 37% during 1997–2012.[10] In Iran, this ratio has been reported to be 1–7 in recent years,[11] with female doctors gradually increasing.[12]

After 1967, some important social changes had an impact on this relationship.[13] The American Nurses Association statement (1980), as an effective organizational stream, emphasized on clinical autonomy and nurse–physician collaborative relationships through the acceptance of separate and combined spheres of activity, responsibility, and accountability.[3] Subsequently, in 1983, the American Academy of Nursing identified a new model that attracted and retained nurses in 41 Magnet hospitals.[14] Recent studies of Magnet hospitals revealed three relational patterns including collaborative, hostile, and student–teacher relationship.[3] However, it may continue to change over time due to the current trends in the position of women in societies.[14]

The studies on Iranian nurses also clarify a poor socioeconomic position of nurses[15,16] and the dissatisfaction of making decisions and professional control levels.[17,18]

In summary, this relationship should be considered as a multidimensional phenomenon that depends on economic, social, and cultural factors, especially the gender distribution at work, which is argued, has remained one of the most effective factors in nurses’ experience. Considering the fact that related studies are mostly on microlevel fields and are conducted by health service researchers who sparsely covered a number of issues, the authors were motivated to design the first study of nurse–physician professional relationship from a sociological viewpoint in Iran.

This study aims to provide answers to the following questions:

What patterns of female nurse–male physician relationship can be found in the Iranian context?

What is the impact of institutional structures (social, economic, and organizational policies) and embodied structures (skills and habits) on the patterns?

How does the agency affect power relations among male physicians and female nurses?

Materials and Methods

Theoretical framework

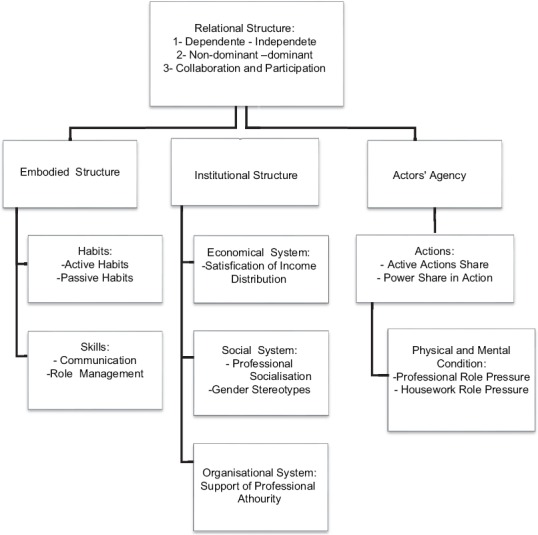

As a core hypothesis, we pursue the idea that nursing reflects broad historical and social changes in the society.[14] Based on Greth and Mills's sociological concept on character and social structure, the professional power assessment in a typical job such as nursing for women and medicine for men clarify their status in the organization and society.[19] According to Lopez and Scott (2000), social structure has three manifestations, namely, institutional, relational, and embodied, which include a wide range of factors, ranging from the microlevel interactions to meso-organizational level, to the macrolevel structures of economical and sociocultural type, including gender.[20] Drawing on the above, the variables are defined in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The theoretical model of effective factors on the patterns of nurse-physician relationship

Dependent variables: Patterns of nurse–physician relationship

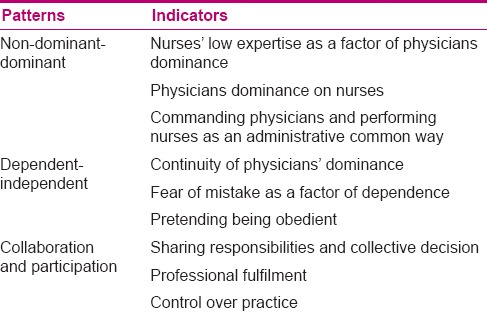

Based on the reviewed literature, along with the findings derived from the in-depth interviews with nurses, a triple scale of the nurse–physician relational patterns was developed. The patterns of the conceptual definitions and the related items are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Indicators of nurse-physician relationship patterns

Non-dominant–dominant pattern

The concept of medical dominance is determined based on two interconnected dimensions, that is, the ability to control its own occupational activities (autonomy) and the control over the work of others (dominance).[21] The physician–nurse relationship is a major image of the medical dominance and the persistence of society traditional structure.[22]

Dependent–independent pattern

The American Nurses Association defined nursing as an independent field of practice in addition to a traditional dependent function, which is linked to physicians.[23] Indeed, nurse's autonomy refers to the ability to act according to one's knowledge and judgment, providing nursing care within the full scope of practice;[24] this can be influenced by policy makers, employers, public expectations, and particularly nurses’ self-confidence and skills.[3] However, some female nurses, despite their expertise, learn consciously or unconsciously to maintain the physicians’ superior status.[2,14]

Collaboration and participation pattern

This pattern describes the interactions in which professionals work together cooperatively with shared responsibility[24] and are provided strategies for professional fulfilment, enhancing autonomy and control over the practice and clinical judgments in work places.[25,26]

Subjects and questionnaire

A survey was conducted on 50 nurses and 50 physicians using a quota sampling method from four hospitals in the capital area. Nevertheless, in the preliminary design, 220 questionnaires were considered, for two groups from 9 hospitals with 5 questioners, during the sampling process (1 May up to 30 June 2009), the scholars succeeded to achieve the acceptance of 67 physicians from 4 hospitals to be surveyed, and from among the distributed questionnaires after 3–5 times of follow-up, approximately 50 physicians and 89 nurses responded completely to the questionnaires. In conformity with the necessity of a balanced distribution in comparative studies, the sample was minimized to 50 female nurses with a bachelor's degree and 50 male physicians who enjoyed a stable employment position with at least 1 year experience in the profession.

Two questionnaires were designed based on the literature, field observations, and an expert panel, which consisted of demographic items including age (years), job experience (years), and socioeconomic status as well as seventy-seven main items on a six-point Likert-type scale with options ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.” All items of the two questionnaires were alike, with the exception of the items concerning the participant's agency which, included the professions’ daily tasks. The data analysis was performed using SPSS version 15 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

The face validity of the questionnaires was evaluated during a pilot study by asking potential responders for clarification. Content validity was achieved based on the theoretical framework, practical literature, and experts’ judgments. The items reliability was confirmed by Cronbach's alpha coefficient (α >0.8).

Ethical considerations

The ethical issues of the study involved providing the purpose, description, and the research design to the participants; ensuring confidentiality and anonymity, participants’ informed consent, and volunteering to take part in the study. Moreover, this study was confirmed by the research committee of the related medical sciences universities.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

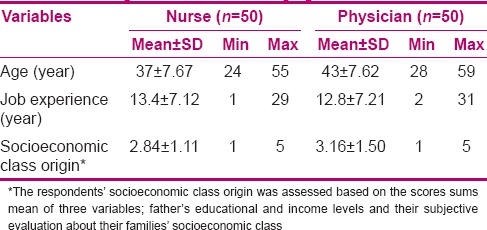

According to Table 2, the nurses had a lower average age (37 years) compared to the physicians (42 years); both groups shared a job experience average of 13 years. In addition, comparing the physicians’ socioeconomic class origin score mean (3.16) with nurses’ (2.84) shows that the physicians belonged to families of a higher socioeconomic status.

Table 2.

The respondents sociodemographic variables

Relational patterns

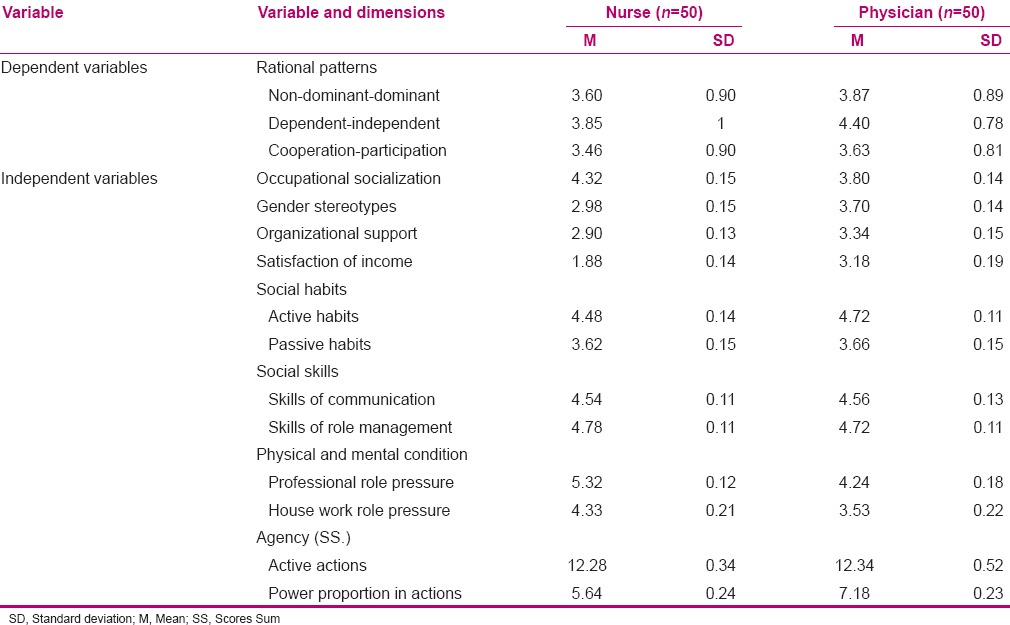

The findings revealed that the highest mean value was related to the independent–dependent pattern and the lowest to that of the cooperation and participation pattern [Table 3]. In addition, the nurses’ multiple regression analysis results clarify occupational socialization, and gender stereotypes offer the greatest determinate factors on the non-dominant–dominant pattern and the physicians’ professional authority, occupational socialization, and organizational support strongly influence this pattern.

Table 3.

The respondents’ characteristics distribution on the dependent and independent variables

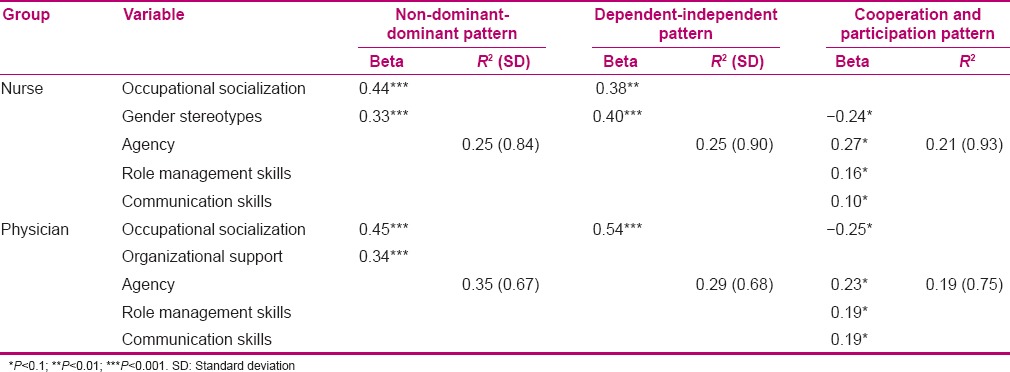

Based on the adjusted R2, the independent variables determine 35% of the changes of first pattern in the physicians and 25% in the nurses [Table 4].

Table 4.

The result of the multiple regression analysis

In the dependent–independent pattern, gender stereotypes and occupational socialization among nurses were noticeably effective. Whereas, according to physicians’ opinions, only occupational socialization was effective. Based on the adjusted R2, the independent variables described 29% of the changes of the first pattern in the physicians and 25% in the nurses group [Table 4].

In regards to the cooperation–participation pattern within the nurses, two variables were distinctly affected; in a positive manner, the agency was an effective factor whereas gender stereotypes created a negative impact. In contrast, occupational socialization negatively affected the physicians’ relational pattern, whereas physicians’ power has a positive effect. In addition, nurses’ role management and communication skills created a positive impact. Alternatively, the physicians’ communication skills provided a negative impact on this pattern. Based on the R2, the independent variables described 19% of changes of second pattern in the physicians and 21% in the nurses [Table 4].

Discussion

Professional socialization and gender

This study findings support the dependent–independent pattern ubiquity. Other studies emphasize an average level of nurses’ clinical decision-making in care process[27] and continuity of a physician-centred culture in Iran.[18] On the other hand, both groups exhibited a moderate level of gender stereotypes [Table 3] supporting the existence of gendered norms and values.

A significant finding that emerged from this study was regarding the gender stereotype factor which distinctly had an impact on the relational patterns, however, while the physicians’ gender stereotypes were in a higher level than those of nurses’ [Table 3]; the impact did not reveal itself in the relational patterns [Table 4]. In other words, only the nurses’ gender stereotypes positively impacted the first and second patterns, and negatively impacted the cooperation and participation pattern. Thus, it seems, the self-confidence variable can be considered as one of authority pillars among Iranian nurses. Therefore, it is mentioned as a root factor of nurses’ powerlessness and the feeling of inferiority toward doctors.[16,17]

On the other hand, while the younger nurses were mostly self-categorized in the cooperation and participation pattern, the older and more experienced nurses were self-categorized in the first and second patterns. Moreover, the occupational socialization has been found as the most effective factor among the physicians.

These results are confirmed by other evidences. Social and cultural factors, organizational culture, and gender socialization in Iran inhibit the nurses’ agency.[18] The element of patriarchy[19] that stabilizes the gendered norms in the educational and organizational systems.[18]

There are some studies that have focused on the improvement of nurses’ decision making skills.[5,28,29] Moreover, the enhancement of collaborative education for medical and nursing students is recommended, particularly in cultures with a hierarchical model of interprofessional relationships.[28]

Distribution of power sources and organization supports

According to the findings, the nurses’ power proportion in actions was lower than those of physicians’. In other words, nurses were considered to be a failed actor, unsuccessful in their interactions, while both groups utilized approximately a similar range of the active actions [Table 3]. It is important to emphasize that while nurses fared worse than the physicians in professional privilege, as well as, wage, administrative support, and professional role pressure confirming other studies,[15,16] there are no noticeable differences regarding their skills and habits levels [Table 3]. This can be associated partly to the similar socioeconomic class and the chances to obtain social skills during their initial socialization [Table 2].

Thus, it seems in spite of female's competences, the opportunities for physicians as a man are better than nurses as a woman in professional spaces. Therefore, traditional structures act as a rewarding system for the dominant role to male physicians. Iranian nurses have frequently argued the organization support would bring them the feeling of confidence.[18] Thus, supportive organizational structures[30] as well as gender equity and positive attitudes toward females’ roles are valued in the society and are the main cores for nurses’ empowerment.[5]

The role of agency in balanced power relationships

Regardless of the data regarding male physicians’ privileges, the findings show that the quality of nurses’ agency affects the cooperation–participation pattern. However, wherever nurses’ gender stereotypes were more severe, the relationship was less likely to follow the third pattern, and whenever the nurses’ authority level increased, the professional relationships were more closely based on the third model [Table 4].

Consequently, the authoritative relationships could be overcome by an individual agency in certain circumstances and compensated for the structural inferiority, most commonly when nurses have adequate expertise.[18] In contrast with the physicians, when the impact of occupational socialization decreased, the agency and the skills of role management and communication became more salient. Indeed, it can be shown as an integrated role of structure and agency in forming social roles and actions.[20]

Another aspect of the study revealed that nurses’ actions were more passive than those of the physicians because of the lack of administrative support and the fear of job loss. In contrast, a few younger physicians complained of younger nurses’ aggressive behaviour or verbal violence. In addition, in the margin of the questionnaire, some nurses added that they routinely ignored physicians’ advice as a balancing act. These findings demonstrate a part of the power source utilized by nurses.

Conclusion

Regardless of its generalizability, this study reveals that there is a paradigm shift in the dynamic of relational and embodied structures, nevertheless the following facts remain stubbornly omnipresent: The nurse–physician relationship pattern is mostly based on the traditional patterns of power relations and gender stereotypes.

The limitation of the study is physicians’ low cooperation to provide consent to be surveyed and a high number of missing data. Thus, this study recommendations include extending qualitative researches and supplementary quantitative studies, systematically restructuring the education curriculums’ of both medicine and nursing to include a value-centred approach toward interdisciplinary collaboration, and defining nurses’ job description based on the advanced standard models which enhance competence in the clinical expertise, promoting economic value of nursing tasks, and reducing work-related pressures. Moreover, fundamentally running on the principles of equity and justice in the society regarding gendered roles is suggested as a long term intervention.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank and extend the heartfelt gratitude to Marnie Barnes Sadri for her very sincere cooperation in editing and summerizing this text, as well as Prof. Baqir Sarukhani, Prof. Mahmood Sadri and Dr. Abo-Ali Vedadhir for their excellent scientific advice and fruitful suggestions.

References

- 1.Purdy N, Spence Laschinger HK, Finegan J, Kerr M, Olivera F. Effects of work environments on nurse and patient outcomes. J Nurs Manag. 2010;18:901–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2010.01172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sirota T. Nurse/physician relationships: Improving or not. Nursing. 2007;37:52–5. doi: 10.1097/00152193-200701000-00040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmalenberg C, Kramer M. Nurse-physician relationships in hospitals: 20000 Nurses tell their story. Crit Care Nurse. 2009;29:74–83. doi: 10.4037/ccn2009436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenstein AH. Nurse-physician relationships: Impact on nurse satisfaction and retention. Am J Nurs. 2002;102:26–34. doi: 10.1097/00000446-200206000-00040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nicolson P. Gender, power and the health care professions. In: Sherr L, Lawrence JS, editors. Women, health and the mind. St. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 2000. pp. 34–45. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coombs M. Power and conflict in intensive care clinical decision making. J Intensive Crit Care Nurse. 2003;19:125–35. doi: 10.1016/s0964-3397(03)00040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Denny E, Earle S. Sociology for nurses. Cambridge: Polity Press; 2005. p. 76. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rappleye E. Gender ratio of nurses across 50 states. [Last accessed on 2015 May 29]. http://www.beckershospitalreview.com .

- 9.U.S. Medical School Applicants and Students 1982-1983 to 2011-2012. [Last accessed on 2015 Oct 11]. Available from: http://www.aamc.org .

- 10.Equation 1 to 7 male to female nurses in the country. [Last accessed on 2013 June 06]. https.//www.tabnak.ir/fa/news .

- 11.Ministry of Health: Entry of women into medicine is limited. [Last accessed on 2016 Sep 01]. http://sharghdaily.ir/News/30873 .

- 12.Stein LI, Watts DT, Howell T. Sounding board: The doctor-nurse game revisited. N Eng J Med. 1990;322:546–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199002223220810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Porter S. Women in a women's job: The gendered experience of nurse. In: Cockerham W, editor. Readings in medical sociology. London: BlackWell Publishers; 2001. pp. 308–18. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nikbakht Nasrabadi A, Emami A, ParsaYekta Z. Nursing experience in Iran. Int J Nurs Pract. 2003;9:78–85. doi: 10.1046/j.1322-7114.2003.00404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gholami Motlagh F, Karim M, Hasanpour M. Iranian nursing students’ experiences of nursing. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2012;17:107–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hassankhani H, Mills J, Dadashzadeh Iranian nurses perception of control over nursing practice. Eur J Sci Res. 2012;75:5–13. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adib-Hagbaghery M, Salsali M, Ahmad F. A qualitative study of Iranian nurses’ understanding and experiences of professional power. Hum Resour Health. 2004;2:9. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-2-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerth HH, Mills CW. Character and social Structure: The Psychology of Social Institutions. Harcourt, Brace & World, Paperback, first Harbinger Books edition. 1964 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lopez J, Scott J. Social structure. Buckingham, Open University Press. 2000;3 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Annandale E. The sociology of health and medicine. Cambridge: Polity Press; 1998. pp. 145–250. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turner B. The vocabulary of complaints: Nursing professionalism and job content. J Sociol. 1986;22:368–86. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Royal College of Nursing: Defining nursing. Vol. 8. London: RCN; 2014. [Last accessed on 2016 Sep 01]. https://www.rcn.org.uk/professional-development/publications/pub-004768 . [Google Scholar]

- 23.Timby BK. Fundamental nursing skills and concepts. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lipincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009. p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weston MJ. Strategies for enhancing autonomy and control over nursing practice. Online J Issues Nurs. 2010;15:13–9. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hojat M, Fields S, Veloski J, Griffith M, Cohen M, Plumb J. Psychometric properties of an attitude scale measuring physician-nurse collaboration. Eval Health Prof. 1999;22:208–20. doi: 10.1177/01632789922034275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mirsaidi G, Lakdizaji S, Ghojazadeh M. How nurses participate in clinical decision-making process. J App Environ Biol Sci. 2012;2:620–4. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wharton AS. Gender inequality. In: Ritzer G, editor. Hand book of social problem: A comparative international perspective. London: Sage Publication; 2004. pp. 162–8. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hojat M, Nasca T, Cohen M, Fields S, Rattner S, Griffiths M, et al. Attitudes toward physician-nurse collaboration: A cross-cultural study of male and female physicians and nurses in the United States and Mexico. Nurs Res. 2001;50:123–8. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200103000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adib Hagbaghery M, Salsali M. A model for empowerment of nursing in Iran. BMC Health Serv Res. 2005;5:24. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-5-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davis K. In: Critical sociology and gender relations: The gender of power. Davis K, Leijenaar M, Oldersma J, editors. London: Sage Publications, First Published; 1991. pp. 65–89. [Google Scholar]