Abstract

Background:

Physical activities among adolescents affects health during pubescence and adolescence and decrease in physical activities among adolescents has become a global challenge. The aim of the present study was to define the relation between the level of physical activity among adolescent girls and their health beliefs as personal factor and level of observational learning as environmental factor.

Materials and Methods:

The present study was a cross-sectional study that was conducted on 400 students aged from 11 to 19 years in Isfahan, Iran. Information regarding the duration of physical activity with moderate/severe intensity was measured in four dimensions of leisure time (exercising and hiking), daily activities, and transportation-related activities using the International Physical Activity questionnaire. Health belief structures included perceived sensitivity, intensity of perceived threat, perceived benefits, and barriers and self-efficacy; observational learning was measured using a researcher-made questionnaire.

Results:

Results showed that perceived barriers, observational learning, and level of self-efficacy were related to the level of physical activity in all dimensions. In addition, the level of physical activity at leisure time, transportation, and total physical activity were dependent on the intensity of perceived threats (P < 0.05).

Conclusions:

This study showed that the intensity of perceived threats, perceived barriers and self-efficacy structures, and observational learning are some of the factors related to physical activity among adolescent girls, and it is possible that by focusing on improving these variables through interventional programs physical activity among adolescent girls can be improved.

Keywords: Adolescent girls, health belief, observational learning, physical activity

Introduction

Regular physical activity has known beneficial effects on physical and mental health of adolescents and improvement of their academic and social performance.[1] The most recognized complication of inactivity, which is obesity, is accompanied with risk of depression[2] and metabolic diseases[3] in adolescents. In addition, it is believed that behavioral risk factors for noncommunicable diseases in adulthood are shaped during childhood and pubescence;[4] therefore, the World Health Organization has recommended that 5–17-year-old individuals should have a moderate to severe physical activity for 60 min per week.[5] However, throughout the lifespan of humans, from childhood to adulthood, physical activities have a clear and obvious downward slope that becomes steeper during pubescence.[6] Reduction in physical activities during pubescence has been reported in many countries; this reduction in physical activities among adolescents has turned into a global health challenge. In Iran also, inactivity has become a serious problem of the modern days,[7] and its rate is higher among girls than boys.[8] Conducted studies have reported that two-third of Iranian girls do not have desirable physical activity during their adolescents years[9] and are exposed to the damages caused by their inactivity. Inactivity among girls, along with undesirable effects on general physical conditions, would also cause gender-related diseases. Studies have shown that girls who had done more hiking during their pubescence suffered from breast cancer less than other girls.[10] Obesity, following inactivity, would increase the risks of pregnancy such as preeclampsia[11] and gestational diabetes.[12] The association of inappropriate physical activity with fertility health and its effect on society's health indicators would emphasize the importance of recognizing its effective factors. Significant efforts have been made toward recognizing the effective factors of physical activity of adolescents. Some studies have also shown that attitude toward physical activity is one of the effective factors of physical activity among different age groups.[13] However, various social and cultural contexts have made the effect of each effective factors on tendency toward physical activity complicated. Desire for computer games among adolescents[14] and social pressures for gaining better academic positions and spending a lot of time learning would affect this group's behaviors. Therefore, planning for improvement of this behavior requires definition of factors that would create more motivation for performing appropriate physical activities. Therefore, considering the fact that personal factors along with environmental factors are effective on incidence of a behavior, the aim of the present study was to evaluate the relationship between the health belief and observational learning on physical activity among adolescent girls.

Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted in January 2015 in Isfahan on 400 adolescent girls who were studying in high schools and aged from 11 to 19 years. This study was approved by the ethics committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. The inclusion criterion was not having any diseases that would restrict physical activities. Samples were selected by random cluster sampling method and all the selected students and their parents provided written and signed informed consent form. The duration of moderate/severe physical activity (minutes per week) was evaluated using the physical activity questionnaire of the World Health Organization.[15] A rate of energy expenditure according to metabolic equivalent (MET) that was more than three was considered moderate/severe physical activity. In addition, exercising and hiking were considered as leisure time activities. Structures of the health belief model including perceived sensitivity, perceived severity of threat, perceived barriers and benefits, self-efficacy, and observational learning were evaluated using a self-report researcher-made questionnaire based on Likert scale (1–5). This questionnaire was designed by reviewing related literature. Content validity and face validity of this questionnaire were evaluated using opinions of health improvement experts and applying their suggestions. Its internal reliability was approved through a pilot study on 20 adolescent girls with a Cronbach's α between 0.75 and 0.82 for all the five structures. In addition, by repeating the study after 1 week, its external reliability with verifiability index (ICC) of 0.82 was approved. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by measuring weight and height. Scores of health belief structures and observational learning were calculated on the basis of 100 and were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 19 (Chicago, IL, USA) and multivariable linear regression statistical test. The level of significance was set at 0.05.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. Also, all subjects signed an informed written consent.

Results

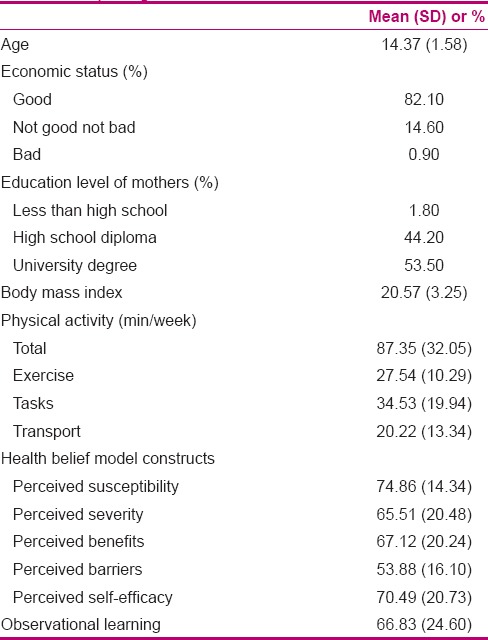

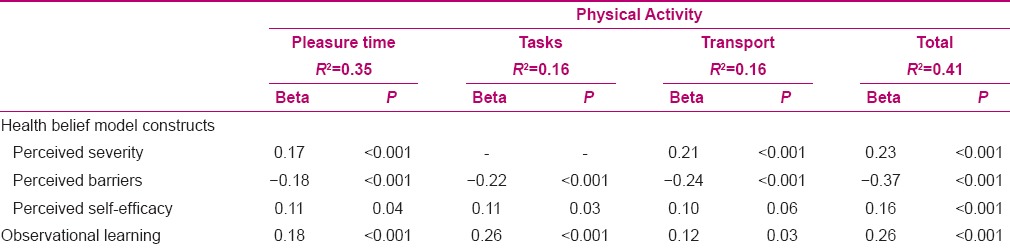

From all the 400 questionnaires that were filled by adolescents, 60 were found distorted and were excluded from the study. The analysis was conducted on the other 340 questionnaires. Participants’ demographic characteristics, that is, mean score of health belief structures, observational learning, and duration of physical activity are shown in Table 1. Evaluating the correlation between health belief structures and duration of moderate/severe physical activity with modification of results for BMI and economic status showed that the duration of leisure time activities among adolescent girls was positively related to the intensity of perceived threat and self-efficacy and it had a reverse and significant correlation with the level of perceived barriers. In addition, the results showed that daily tasks-related activities had a reverse significant correlation with level of perceived barriers and had a positive significant correlation with self-efficacy. Results also showed that the duration of walking among adolescents as a means of transportation had a positive correlation with intensity of perceived threat and a negative correlation with the level of perceived barriers. The total duration of time that was spent for moderate/severe activities had a positive correlation with the intensity of perceived threat and self-efficacy and a negative correlation with the level of perceived barriers. Further, there was a significant positive correlation between moderate/severe physical activities and observational learning [Table 2].

Table 1.

Subjects’ profiles

Table 2.

The relations between physical activity and health belief constructs

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the relation between health belief and observational learning with moderate/severe physical activity among adolescent girls, and the results showed that the two structures of intensity of perceived threat and self-efficacy from health belief structures and observational learning were reinforcing factors of physical activity, and perceived barriers was one of its important deterrents. Regarding the relation between health belief structures and physical activities among youth, results of the present study were in line with the results of Rahmati-Najarkolaei who reported from health belief structures, only the intensity of perceived threats, self-efficacy, and perceived barriers were related to the physical activity of this age group.[16] In addition, another study has shown that the perception of risk of diabetes among adolescents was associated with increase in physical activity.[17]

Based on the results of the present study, the intensity of perceived threat was considered to be an important variable in physical activity among adolescent girls; however, another result of the study showed that from different types of physical activities, leisure time activities were related to the intensity of perceived threat and daily tasks-related activities were not. This result could be because of this general belief that risks of inactivity could simply be prevented by leisure time activities and daily activities do not have any effect on being healthy. Considering the relation between health belief structures and physical activity, especially the key roles of self-efficacy and perceived barriers in incidence of this behavior, it is necessary that health improvement programs be focused at the family level and schools on skills for removing obstacles and gaining self-efficacy of adolescents.

A study by Mostafavi revealed that physical activity among adult women is also affected by their level of self-efficacy.[18] Self-efficacy is one of the most important factors in incidence of different behaviors and is considered to be an important element in many behavioral models;[19] results of this study also approved its role in showing physical activity-related behaviors. Conclusion of the results showed that among different age groups, perceived barriers in younger women was the determining factor for physical activity more than other age groups, which could be caused by social pressure on students for academic successes and spending a lot of time to achieve these goals.

Another result of this study revealed that observational learning was an important factor in physical activity habits of adolescent girls. Results showed that having the opportunity of learning by watching others like parents, friends, and other relatives would increase physical activity. Parents have a key role in socializing adolescents and are appropriate role models for teaching them physical activities.[20] This study mentioned that parents could also be an effective role model in formation of physical activity habits. A qualitative study also showed that one of the most important factors in motivation or exercising was having a model to follow.[21] A longitudinal study on Scottish adolescents indicated that peers and parents are effective for performing physical activities.[22]

Conclusion

The present study showed that physical activity improvement programs for adolescent girls could only be successful when they are planned by focusing on individual factors like perceiving the risks of inactivity and creating a condition for decreasing perceived barriers and increasing their level of self-efficacy along with creating an opportunity for observing the behaviors of key individuals like parents and friends.

Financial support and sponsorship

Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (grant number: 393696).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences for funding the survey.

References

- 1.Domazet SL, Tarp J, Huang T, Gejl AK, Andersen LB, Froberg K, et al. Associations of physical activity, sports participation and active commuting on mathematic performance and inhibitory control in adolescents. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0146319. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alghadir AH, Gabr SA, Al-Eisa E. Effects of physical activity on trace elements and depression related biomarkers in children and adolescents. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s12011-015-0601-3. [ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steinberger J, Daniels SR, Eckel RH, Hayman L, Lustig RH, McCrindle B, et al. American Heart Association Atherosclerosis, Hypertension, and Obesity in the Young Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; and Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism. Progress and challenges in metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association Atherosclerosis, Hypertension, and Obesity in the Young Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; and Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism. Circulation. 2009;119:628–47. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.191394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Loughlin JL, Tarasuk J. Smoking, physical activity, and diet in North American youth: Where are we at? Can J Public Health. 2003;94:27–30. doi: 10.1007/BF03405048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Global recommendations on physical activity for health. [Last accessed on 2010 Oct 08]. Available from: http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/factsheet_recommendations/en/index.html .

- 6.Kimm SY, Glynn NW, Kriska AM, Barton BA, Kronsberg SS, Daniels SR, et al. Decline in physical activity in black girls and white girls during adolescence. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:709–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa003277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Momenan AA, Delshad M, Mirmiran P, Ghanbarian A, Azizi F. Leisure time physical activity and its determinants among adults in Tehran: Tehran lipid and glucose study. Int J Prev Med. 2011;2:243–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Azizi F, Ghanbarian A, Momenan AA, Hadaegh F, Mirmiran P, Hedayati M, et al. Prevention of non-communicable disease in a population in nutrition transition: Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study phase II. Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study Group. Trials. 2009;10:5. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-10-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahmadnia E, Shakibazadeh E, EmamgholiKhooshehcheen T. Life style-related osteoporosis preventive behaviors among nursing and midwifery students. Hayat. 2010;15:59–60. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boeke CE, Eliassen AH, Oh H, Spiegelman D, Willett WC, Tamimi RM. Adolescent physical activity in relation to breast cancer risk. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;145:715–24. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-2919-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poorolajal J, Jenabi E. The association between body mass index and preeclampsia: A meta-analysis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;13:1–20. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2016.1140738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huvinen E, Grotenfelt NE, Eriksson JG, Rono K, Klemetti MM, Roine R, et al. Heterogeneity of maternal characteristics and impact on gestational diabetes (GDM) risk-Implications for universal GDM screening? Ann Med. 2016;48:52–8. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2015.1131328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hosseini M, Khavari Z, Yaghmaei F, AlaviMajd H, Jahanfar M, Heidari P. Correlation between attitude, subjective norm, self-efficacy and intention to physical activity in female students. JHPM. 2013;3:52–61. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bassett DR, John D, Conger SA, Fitzhugh EC, Coe DP. Trends in physical activity and sedentary behaviors of United States youth. J Phys Act Health. 2015;12:1102–11. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2014-0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjöström M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:1381–95. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rahmati-Najarkolaei F, Tavafian SS, GholamiFesharaki M, Jafari MR. Factors predicting nutrition and physical activity behaviors due to cardiovascular disease in Tehran university students: Application of health belief model. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2015;17:e18879. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.18879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fischetti N. Correlates among perceived risk for Type 2 diabetes mellitus, physical activity, and dietary intake in adolescents. Pediatr Nurs. 2015;41:126–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mostafavi F, Ghofranipour F, Feizi A, Pirzadeh A. Improving physical activity and metabolic syndrome indicators in women: A transtheoretical model-based intervention. Int J Prev Med. 2015;6:28. doi: 10.4103/2008-7802.154382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice. 4th ed. San Fransisco, CA: Wiley & Sons; 2008. Models of individual health behavior. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pugliese JA, Okun MA. Social control and strenuous exercise among late adolescent college students: Parents versus peers as influence agents. J Adolesc. 2014;37:543–54. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bengoecheaa EG, Streanb WB. On the interpersonal context of adolescents’ sport motivation. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2007;8:195–217. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kirby J, Levin KA, Inchley J. Associations between the school environment and adolescent girls’ physical activity. Health Educ Res. 2012;27:101–14. doi: 10.1093/her/cyr090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]