Abstract

Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms (GEP-NEN), considered a heterogeneous neoplasia, exhibit ill-defined pathobiology and protean symptomatology and are ubiquitous in location. They are difficult to diagnose, challenging to manage, and outcome depends on cell type, secretory product, histopathologic grading, and organ of origin. A morphologic and molecular genomic review of these lesions highlights tumor characteristics that can be used clinically, such as somatostatin-receptor expression, and confirms features that set them outside the standard neoplasia paradigm. Their unique pathobiology is useful for developing diagnostics using somatostatin-receptor targeted imaging or uptake of radiolabeled amino acids specific to secretory products or metabolism. Therapy has evolved via targeting of protein kinase B signaling or somatostatin receptors with drugs or isotopes (peptide-receptor radiotherapy). With DNA sequencing, rarely identified activating mutations confirm that tumor suppressor genes are relevant. Genomic approaches focusing on cancer-associated genes and signaling pathways likely will remain uninformative. Their uniquely dissimilar molecular profiles mean individual tumors are unlikely to be easily or uniformly targeted by therapeutics currently linked to standard cancer genetic paradigms. The prevalence of menin mutations in pancreatic NEN and P27KIP1 mutations in small intestinal NEN represents initial steps to identifying a regulatory commonality in GEP-NEN. Transcriptional profiling and network-based analyses may define the cellular toolkit. Multianalyte diagnostic tools facilitate more accurate molecular pathologic delineations of NEN for assessing prognosis and identifying strategies for individualized patient treatment. GEP-NEN remain unique, poorly understood entities, and insight into their pathobiology and molecular mechanisms of growth and metastasis will help identify the diagnostic and therapeutic weaknesses of this neoplasia.

Keywords: Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms, Blood, Carcinoid, Ki-67, Proliferation, Somatostatin, Transcriptome

Abbreviations used in this paper: Akt, protein kinase B; BRAF, gene encoding serine/threonine-protein kinase B-Raf; cAMP, adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate; CgA, chromogranin A; CGH, comparative genomic hybridization; CREB, cAMP response element-binding protein; D cell, somatostatin; DAG, diacylglycerol; EC, enterochromaffin; ECL, enterochromaffin-like; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; ERK, extracellular-signal-regulated kinase; G cell, gastrin; GABA, γ-aminobutyric acid; GEP-NEN, gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms; GPCR, G-protein coupled receptor; 5-HT, serotonin, 5-hydroxytryptamine; IGF-I, insulin-like growth factor-I; ISG, immature secretory vesicles; LOH, loss of heterozygosity; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; MEN-1/MEN1, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1; miR/miRNA, micro-RNA; MSI, microsatellite instability; MTA, metastasis associated-1; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; NEN, neuroendocrine neoplasms; NFκB, nuclear factor κB; PI3, phosphoinositide-3; PET, positron emission tomography; PI3K, phosphoinositide-3 kinase; PKA, protein kinase A; PKC, protein kinase C; PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10; SD-208, 2-(5-chloro-2-fluorophenyl)-4-[(4-pyridyl)amino]p-teridine; SNV, single-nucleotide variant; SSA, somatostatin analog; SST, somatostatin; TGF, transforming growth factor; TGN, trans-Golgi network; TSC2, tuberous sclerosis complex 2 (tuberin); VMAT, vesicular monoamine transporters; X/A-like cells, ghrelin

Summary.

Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms exhibit a unique neoplastic profile that is substantially different to other epithelial cancers. In the absence of common activating mutations, defining the cellular toolkit and the nexus/master regulator genes is vital to understand and clinically target them.

The Carcinoid Conundrum in Context

Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms (GEP-NEN) are generally considered to be anomalous neoplasia, given their unusual pathobiology that exhibits both secretory and proliferative phenotypes. In addition, they display divergent clinical courses, ranging from indolent to highly aggressive.1 Their protean symptomatology and ubiquitous sites of origin render them difficult to diagnose and vexatious to manage.2 Because they arise from different organs and diverse neuroendocrine cell types, each with their own unique transcriptome, the biologic behavior of these neoplasia is often unpredictable, and their outcome is variable and uncertain, irrespective of treatment.3

GEP-NEN present a paradox in that they are semantically grouped as one neoplastic category yet represent numerous different tumors that share only their neuroendocrine origin as a commonality (Table 1). Anatomically, these tumors arise from a variety of different neuroendocrine cells in diverse locations throughout the gastroenteropancreatic system. Functionally, they each produce a variety of different amine and peptide secretory products, some of which produce substantial clinical symptomatology or alterations in metabolic activity. Diverse regulatory systems to modulate the secretory process exist for the different cell systems. Proliferation is also different in each system and can range from indolence to almost completely unregulated growth with aggressive invasion and diverse metastatic events. A wide variety of proliferative regulatory systems have been defined that differ among the cell types and individual tumors. Until recently, the majority of knowledge about the regulation of secretion and proliferation was descriptive, with little mechanistic information available. More recently, the application of sophisticated strategies for exploring the transcriptome, micro-RNome (miRNome), and exome have yielded better insights into secretory and proliferative regulation at a genomic level. Nevertheless, a paucity of information characterizes our current state of understanding of these lesions. In particular, there is little appreciation of the molecular basis by which transformation from a naïve cell type to a neoplastic phenotype occurs. Resolution of this issue remains a paramount scientific concern.

Table 1.

Heterogeneity and Diversity in Gastrointestinal and Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors

| Tumor | Putative Cell of Origin | Localization | Secretory Products | Secretory Regulation | Proliferative Regulation | Omics-Based Analyses | Mutations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small intestinal NEN, “carcinoid” | Enterochromaffin (EC) | Entire GI tract | Serotonin, substance P, guanylin, melatonin | Immune (eg, IL1β), mechanical (eg, ATP), neural (eg, adrenaline), somatostatin (PKA, MAPK) | TGFβ, EGFR (RAS/RAF/MAPK, GL1/SNAIL) | Transcriptome, LOH, exome, miRNAome | CDKN1B |

| Nonfunctional pancreatic NEN | Precursor (ductal) cell or omnipotent stem cell | Pancreas | None defined | Calcium dependent | Growth factors (eg, VEGF), PI3K, Akt, mTOR | Transcriptome, LOH, exome, miRNome | MEN-1, DAXX, ATRX |

| Colorectal NEN | L, EC | Colon-rectum | GLP-1, PYY, NPY | Nutrient sensinga | EC: ATM) | EC: Transcriptome, LOH, exome, miRNome | — |

| ECLoma (type I–III) | Enterochromaffin-like (ECL) | Gastric fundus | Histamine | Gastrin, muscarinic, vagal (PI3K/DAG/calcium signaling), somatostatin | Gastrin, PACAP, histamine, EGFR (MAPK) | Transcriptome, LOH | None (type II: MEN-1) |

| Gastrinoma | Gastrin (G) | Gastric antrum and duodenum, pancreas | Gastrin | Environmental (amino acids, tastants, calcium, pH), mechanical, vagal (PKA, MAPK, calcium signaling), somatostatin | IGF-1 | Transcriptome, LOH | MEN-1 |

| CCKoma | I | Duodenum | CCK | Environmental (amino and fatty acids), vagal | — | — | — |

| GIPoma | K | Duodenum, jejunum | GIP | Nutrient sensinga | — | — | — |

| Insulinoma | Beta | Pancreas | Insulin | GIP, GLP-1, leptin, somatostatin (depolarization, calcium) | mTOR | Transcriptome, LOH, exome | YY1 |

| Glucagonoma | Alpha | Pancreas | Glucagon | GIP, GLP-1, somatostatin (depolarization, calcium) | — | Transcriptome, LOH | MEN-1 |

| Somatostatinoma | Delta | Pancreas | Somatostatin | — | Src family kinases, PI3K-mTOR, MEK | — | NF-1 |

| Somatostatinoma | Delta (D) | Duodenum | Somatostatin | — | Src family kinases, PI3K-mTOR, MEK | — | — |

| Ghrelinoma | Ghrelin (Gr) | Entire GI tract | Ghrelin | β1-adrenergic receptor | — | — | — |

| PPoma | PP | Pancreas | PP | — | — | — | — |

| VIPoma | VIP | Entire GI tract (pancreas, adrenal) | VIP | — | — | — | — |

Note: Akt, protein kinase B; ATM, ataxia telangiectasia mutated kinase; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; ATRX, alpha thalassemia/mental retardation syndrome X-linked; CCK, cholecystokinin; DAG, diacylglycerol; DAXX, death-domain associated protein; EC, enterochromaffin; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; GI, gastrointestinal; GIP, gastric inhibitory peptide; GLP-1, glucagon-like peptide 1; IGF, insulin-like growth factor; IL, interleukin; LOH, loss of heterozygosity; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; MEK, mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase; MEN-1/MEN1, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; PP, pancreatic polypeptide; PYY, polypeptide YY (tyrosine, tyrosine); NEN, neuroendocrine neoplasms; NF-1, nuclear factor 1; NPY, neuropeptide Y (tyrosine); PACAP, pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide; PI3K, phosphoinositide-3 kinase; PKA, protein kinase A; PP, pancreatic polypeptide; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; VIP, vasoactive intestinal peptide; YY1, Yin Yang 1 transcriptional repressor; —, no data.

Signaling pathways associated with nutrient sensing are poorly characterized.

GEP-NEN comprise ∼1% of all malignancies and represent the second most common gastrointestinal malignancy after colorectal cancer.4 It has also been accepted that they are increasing in incidence1, 5, 6, 7 (estimated annually at ∼5%8) and that the majority (≥95%) are of sporadic etiology.1 The diagnosis of NEN remains a challenge, given the often subtle and protean clinical manifestations,9 and the current understanding of this neoplastic group is defined more by what is not known (ie, “not typical and/or unusual” presentation and behavior) rather than what is known. Tumors of the same organ behave differently. For example, β-cell pancreatic neoplasms (insulinomas) are different from G-cell tumors (gastrinomas) of the pancreas in both symptomatology and malignancy. The former are invariably benign, and the latter are indubitably malignant.10 The common symptoms are protean and easily mistaken for other conditions, such as when flushing or diarrhea are mistaken for symptoms of menopause or irritable bowel syndrome, respectively. As a consequence of tardy recognition of these tumors (the majority are metastatic when identified), clinical management is a Sisyphean task given the advanced nature of the disease and the paucity of effective therapeutic strategies.9

NEN are heterogeneous whether viewed from a genetic, biochemical, cellular (proliferation, metastases), organ site, or symptomatic perspective.11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19 They are difficult to diagnose and manage, and surgery represents the only known “cure.”20, 21, 22 Standard clinical approaches to monitor treatment responses are inadequate (limited biomarker spectrum) and relatively insensitive (limited image discriminant index).23 Radiological Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors v1.1 (RECIST) criteria are insensitive for measuring treatment responses in these often “indolent” lesions.24 Response to therapies is rarely associated with early measurable (detectable) changes in tumor size and represents a substantial limitation in GEP-NEN management.25, 26

The recognition of somatostatin receptors as key regulators of NEN function provided an effective therapeutic strategy in terms of secretory inhibition, symptomatic control, and quality of life improvement.27 The impact of such agents (somatostatin analogs) on the proliferative regulation of NEN has also been clinically demonstrated as having some degree of efficacy.28, 29 Other agents (everolimus, sunitinib, bevacizumab, gefitinib) euphemistically considered as targeting specific proliferative pathways in NEN have proved of relatively modest benefit given their marginal efficacy and substantial adverse-event profile.30, 31, 32, 33, 34 A critical shortcoming in the latter strategy is the inability to identify before treatment whether the “target” exists.

Overall, the lack of effective agents represents the limited understanding of the biologic basis of NEN and the paucity of information as to the molecular nature of the disease.35 This disappointing situation has arisen for two reasons. First, the limited financial investment in exploring a disease therapy reflects its perceived low incidence and health-care impact on the population. Second, NEN disease in itself presents a formidable investigative problem. Individual neoplasms arise from a plethora of different cell types (albeit with a common neuroendocrine element) and organs systems. They exhibit different regulatory systems, and their rarity has inhibited the acquisition of large specimen samples needed for identification of molecular mechanisms. The fact that they arise from the diffuse neuroendocrine system, which itself is poorly characterized and little understood, has compounded the investigative problem.36

The scientific conundrum of these neoplasms is further amplified by the diverse observations with respect to their differences from other forms of cancer in epidemiology, biology, and behavior. Typically, the incidence rates of cancer are nonlinear, and not all multicellular organisms develop neoplasia. This disconnect between body mass (which is a surrogate for cell number) and cancer incidence is known as Peto’s paradox37; this identifies that natural selection favors against carcinogenesis. NEN, however, do not conform to the declining acceleration model of cancer development evident in the majority of neoplasia.38 Instead, these neoplasms tend to occur later than other cancers (usually >60 years of age) and continue increasing in incidence with age (risk as high as 7 out of 100,000 in the seventh decade).1, 8 Indeed, the frequency of these neoplasms has been reported to be as high as 1% in the population (at autopsy).39 Such a high prevalence is more consistent with timed exposure per Peto’s experiments than to any paradox. It is also evident that the proportion of neuroendocrine cells in the body—which is estimated at ∼1% 40—closely mirrors the proportion of cancers that develop with neuroendocrine features (1%). Thus, it seems likely that this class of neoplasms (neuroendocrine) may not be regulated by the same rules that govern the development of more common cancers and that it represents a different neoplastic phenomenon compared with the classic “hit theory” mutation-driven oncologic paradigm.

In this appraisal of the state of neuroendocrine neoplasia, we seek to examine the unique nature of NEN and scrutinize the evidence indicating their differences from the accepted cancer model. The goal is to elucidate whether NEN disease is actually different from other cancers or whether this is simply a presumption that has evolved out of misinterpretation of available data, a paucity of information, or an example of oncologic dialetheism.41 Our thesis is that molecular advances are necessary to advance the understanding of the disease and that, in particular, the development of a molecular toolkit for these neoplasms will prove to be the appropriate pathway to the development of effective diagnosis and therapy.

Functional Cellular Morphology

The term “neuroendocrine” is a composite description of a cell that exhibits mixed morphologic and physiologic attributes of the neural and endocrine regulatory systems. The bicameral cell includes a neural cell phenotype expressing proteins that include neuron-specific enolase, synaptophysin, chromogranin A (CgA), and neuronal filament proteins such as internexin α. In addition, they express a physiologic “hormone” phenotype classically ascribed to endocrine cells.42

Structurally, neuroendocrine cells can either be “open” or “closed” to the lumen. Most intestinal enterochromaffin (EC) and D (somatostatin) cells and gastric G (gastrin) cells are of the open type, with apical cytoplasmic extensions that project into the glandular lumen with short microvilli and allow the cell to sense physical or chemical variations in luminal content.43 The neuronal component is represented at the basal aspect of the cells by often extensive and elongated axon-like cytoplasmic processes that abut adjacent cells.44 Multiple processes, which can extend up to 50–80 μm in length, often possess a terminus resembling a synaptic-like bouton that likely interacts with adjacent non-neuroendocrine cells.45 These dendritic-like processes embody the neuronal component of the neuroendocrine cell whereby signal substances are delivered in direct proximity to other coexistent neural filaments in the lamina propria or contiguous mucosal cells and the immune cells.46

Closed cells include the majority of fundic neuroendocrine cells, the enterochromaffin-like (ECL) cell as well as the gastric D, EC, and X/A-like (ghrelin) cells. Such cells do not access the lumen but are regulated by basal neural and hormonal signals. Like open cells, however, they also exhibit long, axon-like processes that regulate the function of other cell types.47 Tumor cells, similar to normal neuroendocrine cells, exhibit almost all the morphologic characteristics of neural and endocrine cell types, including secretory machinery as well as axonal structures such as internexin α expression.48 Assessment of the secretory profile provides the basis for the much-used clinical measurements of, for example, the granin family or amines such as 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT, serotonin).49 However, the pathobiologic relevance of their neural characteristics remains largely uninvestigated. It is likely that tumor cells both directly sense and “taste” the lumen,43, 50 transduce these messages (albeit in an uncontrolled, paroxysmal fashion), and modulate the behavior of mucosal cells such as inflammatory cells or cells involved in the regulation of nociception and motility. These local events and the systemic secretory products provide the basis for the clinical features (such as pain and diarrhea) evident in some GEP-NEN.1

Mechanistic Secretory Matrix

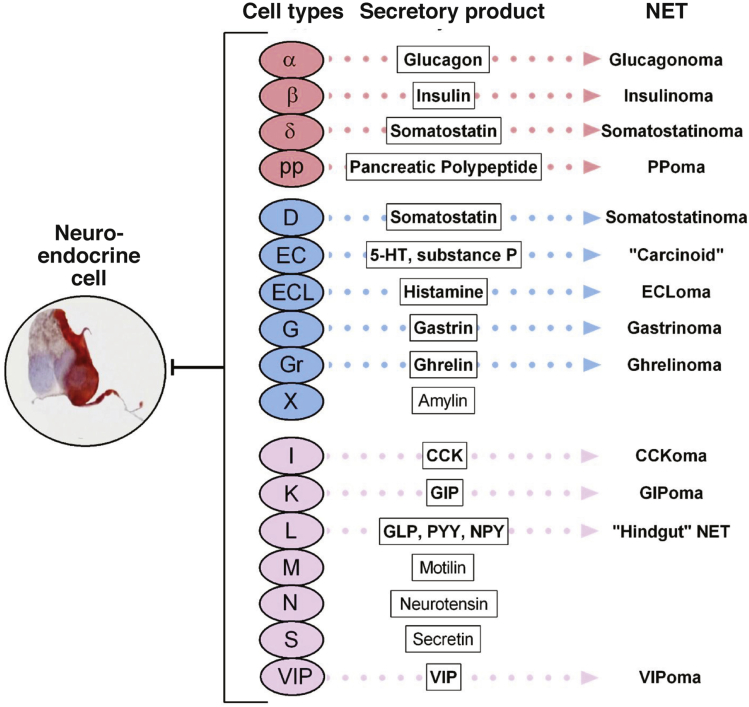

At least 17 individual neuroendocrine cell types have been identified within the gastrointestinal tract and pancreas, reflecting the plethora of bioactive amines and peptides they synthesize and secrete (Figure 1). Secretory products are stored in large dense-core vesicles or in small synaptic-like vesicles.51 Large dense-core vesicles bud from the trans-Golgi network (TGN) where prohormones and proneuropeptides are processed and stored. Although some granules store individual peptide hormones, several different peptides or amines may be colocalized.52, 53 CgA is a key constitutive protein involved in the biogenesis of dense-core secretory granules at the level of the TGN. Amines are accumulated in secretory vesicles via type I vesicular monoamine transporters (VMAT1 in EC cells, VMAT2 in ECL cells) and may be colocalized in large dense-core vesicles or processed into small synaptic-like vesicles.

Figure 1.

Gastrointestinal and pancreatic neuroendocrine cell types, secretory products, and associated neoplasms. CCK, cholecystokinin; GIP, gastric inhibitory peptide; GLP-1, glucagon-like peptide 1; NPY, neuropeptide Y (tyrosine); PP, pancreatic polypeptide; PYY, polypeptide YY (tyrosine, tyrosine).

(Image courtesy of Hauso et al.47)

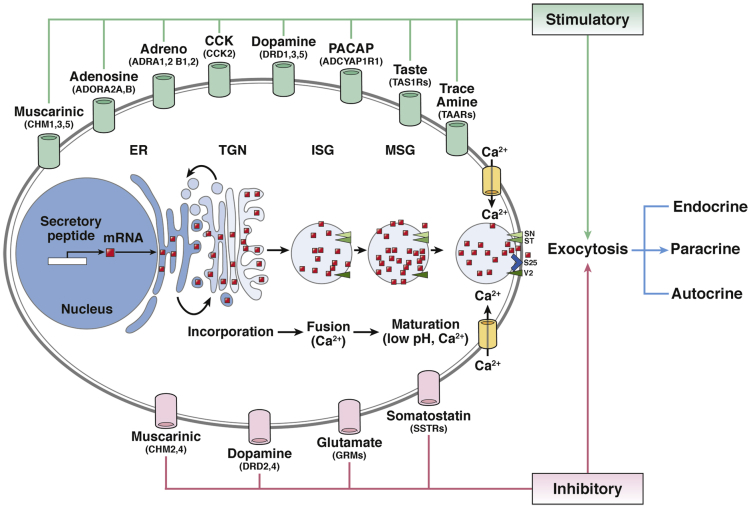

The process of neuroendocrine cell secretion is best exemplified by CgA,54 which (often with CgB) initially accumulates in the TGN before incorporation into immature secretory vesicles (ISG). In the ISG, chromogranins bind to low-affinity vesicle membrane receptors, initiating the sorting of other ISG proteins to the regulated secretory pathway (Figure 2). Further development of ISG into mature secretory granules involves calcium (Ca2+) influx, granule acidification, prohormone processing (including chromogranins themselves), and the uptake of amines (eg, 5-HT). Thereafter, after receptor-mediated Ca2+ influx, matured granules dock at the cell membrane via expression of syntaxin, synaptotagmin, vesicle-associated membrane protein 2 (VAMP2), and synaptosomal-associated protein, 25-kDa (SNAP25) with release of their contents into the extracellular milieu.55

Figure 2.

Mechanistic basis of secretory regulation in a neuroendocrine cell. Initial transcription and processing occurs in the nucleus and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and thereafter secretory products accumulate in the trans-Golgi network (TGN). Subsequently, they are incorporated into immature vesicles that also contain other protein products destined for immature secretory vesicles (ISG). Multiple ISGs fuse into a mature secretory granule (MSG) in a process that involves calcium (Ca2+) influx, granule acidification, and prohormone processing as well as amine uptake (eg, serotonin). This sequence of processes is directed via positive regulatory inputs from diverse regulatory G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) (green). Ligand binding activates both signal pathways (PKA/cAMP, MAPK, PI3K/DAG/PKC) and membrane depolarization. Regulatory GPCRs are typically cell-type specific and include muscarinic, tastant, and trace amine receptors. Consequent upon activation MSGs are directed to the plasma membrane, and, after receptor-mediated Ca2+ influx, docking occurs at the cell membrane. This process involves the expression of a series of proteins including syntaxin (SY), synaptotagmin (ST), vesicle-associated membrane protein 2 (VAMP2) (V2), and synaptosomal-associated protein, 25-kDa (SNAP25) (S25) (green arrowheads). The ensuing vesicle-and-membrane fusion process culminates in MSG release of contents into the extracellular milieu (exocytosis). Inhibition of secretion occurs through a number of GPCRs (pink) (somatostatin > muscarinic > glutamate) which upon activation reverses the signaling pathway initiation process through dephosphorylation of signaling intermediates as well as inactivation of voltage-gated channels. Red dots = secretory protein. IUPHAR gene symbols are included for each of the GPCRs.

Tumor cells, like their normal counterparts, synthesize and secrete a similar diverse array of bioactive products. However, processing in neoplastic cells differs from not only normal cells but between individual tumor cell types. Thus, CgA processing varies between different neuroendocrine tissues such that there is more extensive cleavage in pancreatic islets than in the adrenals, and different fragment profiles exist for each of the pancreatic α, β, D, and pancreatic polypeptide cells.56 This differential processing has implications for the accurate biochemical measurements of secretory product.57 Of biologic relevance, however, is that the smaller biologically active peptides (eg, vasostatin I and II, or chromostatin)58, 59 differentially regulate tumor cell proliferation and metastasis.60

Membrane Receptor Regulation

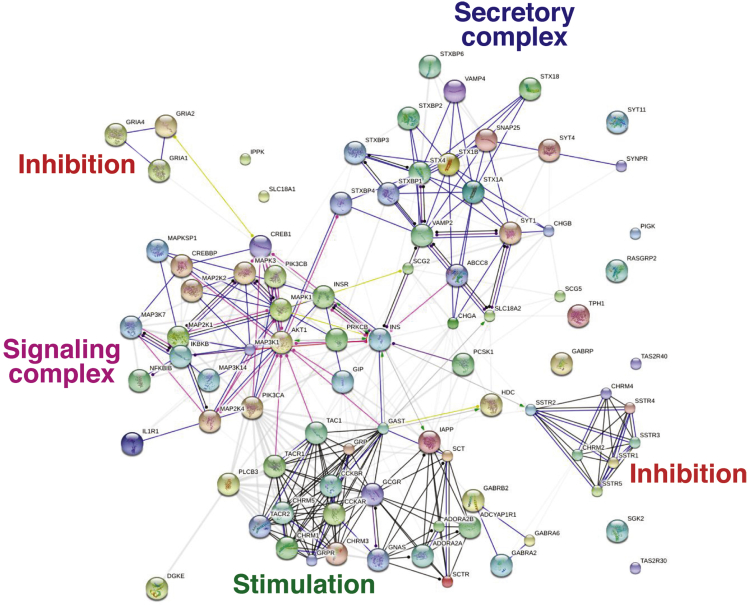

Secretion is regulated by G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs), ion-gated receptors, and receptors with tyrosine kinase activity.61 An interactomic map of the known regulators of secretion can be built to visualize this machinery, providing an overview of the “secretome” (Figure 3). Overall, secretory regulation includes tightly interrelated inputs from stimulatory receptors, which activate signaling pathways leading to exocytosis. The latter phenomenon is characterized by well-defined processes, including vesicular amine uptake, vesicle formation, migration, and docking with release of contents.

Figure 3.

Protein interactomes involved in neuroendocrine neoplasm secretion.Secretory regulation includes tightly interrelated inputs from stimulatory receptors, including cholecystokinin, muscarinic, adenosine (AdoR-A), pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP), and GABA receptors (stimulation). These activate signaling pathways (signaling) including MAPK/PKC, PKA/cAMP/CREB, NFκβ, and PI3K activity. Secretion is activated through well-defined processes that include vesicular amine uptake, vesicle formation, migration, docking, and exocytosis. Inhibition occurs at the level of signaling and involves somatostatin—inhibition of protein kinase C—and the ionotropic glutamate receptor family (ligand-gated ion channels and depolarization). Created with protein/transcripts identified in neuroendocrine neoplasms and String 9.1.213

Individual neuroendocrine cell types may differ in terms of signaling inputs, but the majority of pathways are conserved. In some neuroendocrine cell types, such as gastric G-cells, GPCRs activate protein kinase A (PKA) and adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (cAMP) production with downstream activation of the ERK1/2 (extracellular-signal-regulated kinase 1/2: mitogen-activated protein kinase, MAPK) pathways. In other types, such as gastric ECL cells, the phosphoinositide-3 kinase/diacylglycerol/protein kinase C (PI3K/DAG/PKC) pathways, and downstream, Ca2+ flux regulation (either an internal influx of calcium through calcium channels, or IP3-mediated efflux of calcium into the cytoplasm from endoplasmic stores) is activated.62 Membrane depolarization, as in pancreatic β-cells, can also ensue as ion-gated receptors are activated (eg, Sur/K+ receptors or γ-aminobutyric acid [GABA]-mediated Na+/K+ channel activators) with calcium entry.63 These pathways often involve mononucleotide signalers such as cyclic guanosine 3′,5′-monophosphate. The latter cells call also be hormonally regulated (incretins) via gastric inhibitory peptide and glucagon-like peptide-1.64

Receptors with tyrosine kinase activity initiate PKC pathway activation, leading to downstream effects that include phosphorylation of multiple proteins involved in granule maturation, migration, and docking to the membrane.65 Cytokines and bacterial products may also affect secretion, largely through nuclear factor κB (NFκB) signaling pathways.46 Activation of these pathways is not limited to secretion but may also activate transcription of enzymes involved in amine production, such as cAMP-mediated cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) transcriptional regulation of tryptophan hydroxylase (TPH1, the rate-limiting enzyme in 5-HT synthesis)66 or PKC-mediated phosphorylation (and stabilization half-life and thus activity) of this enzyme. Other pathways such as MAPK are involved in transcriptional regulation of HDC (histidine decarboxylase), the histamine biosynthetic enzyme.

Activating receptors include β-adrenoreceptors, purinergic receptors (A2-A/B adenosine receptors, AdoR-A2A/B),67 and interleukins (IL-1β/2). These responses (activation of transcription and secretion) are largely regulated by Ca2+ influx, PKA/cAMP, ERK1/2, and NFκB signaling pathways. Secretagogue-evoked stimulation induces actin reorganization through sequential ordering of carrier proteins at the interface between granules and the plasma membrane, allowing for membrane trafficking and culminating in release of neuroendocrine contents.68

Secretory inhibition is prototypically initiated via somatostatin (acting dominantly via the somatostatin 2 [sst2] receptor), acetylcholine (muscarinic M4 receptors, but also can be stimulatory via M3 receptors), and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA, via GABAA receptors).69 Blockade of secretion occurs through inhibition of pathways involved in stimulating secretion. This includes inhibition of intermediate signaling such as cAMP (through dephosphorylation of PKA) or PKC inactivation (dephosphorylation) with reversals of Ca2+ influx.70 The latter can also occur through membrane repolarization and inhibition of voltage-gated L-channels.71

Mechanistic Basis of Proliferative Regulation

Proliferative regulators of GEP-NEN are, for the most part, poorly understood. The two best characterized and described are gastrin and gastric ECL cells and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) on the small bowel EC cell. Gastrin, via the cholecystokinin 2 (CCK2) receptor, is the principal regulator of ECL cell proliferation via a MAPK-activated signal transduction cascade72 and induction of the activator protein-1 (AP-1) complex (a FOS/JUN-mer) transcription factor.73 The latter regulate the genes necessary for cell cycle progression (eg, cyclin genes).74 Physiologic ECL cell proliferation is associated with fos/jun transcription activation by the MAPK pathway (ERK1/2) after gastrin-mediated Ras activation.75 Such proliferation rarely, if ever, leads to neoplastic progression and morphologic appearances of neoplasia are not associated with metastatic progression.76 In some circumstances, a mutation or loss of function of the menin gene represents an inherent “hit,” and hypergastrinemia culminates in the development of type II gastric carcinoids (Zollinger–Ellison syndrome/multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 [ZES/MEN-1]) with a classic neoplastic (invasive/metastatic) phenotype.77 Under such conditions, diffuse ECL cell proliferative changes are evident; at least linear and micronodular hyperplasia are noted in >50%, and invasive gastric carcinoids occur in ∼25%.78 Gastrin-producing tumors (eg, gastrinomas) appear to be regulated by insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I).79

The physiologic proliferative regulation of small intestinal EC cells is largely unknown, but TGF-β1-mediated growth inhibition appears a key component.80 TGF-β1 is a potent stimulator of neoplastic EC cell proliferation and functions to decrease expression of SMAD family member 4 (SMAD4) with concomitant increased expression of the inhibitor of SMAD nuclear translocation, SMAD7.80 TGF-β1 down-regulates P21WAF1/CIP1 transcription and increases expression of c-Myc, resulting in phosphorylation and cross-activation of the ERK1/2 signaling pathway. This culminates in downstream activation of malignancy-defining genes such as MTA1 (metastasis associated 1). Once transformed into a neoplastic phenotype, EC-derived-NEN are characterized by a loss of responsiveness to TGF-β1.80

HER1 (EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor) is expressed in the majority (>80%) of small intestinal and rectal NEN.81, 82, 83 At a molecular level, EGFR aneusomy occurs in ∼20% of cases, and an elevated EGFR copy number has been noted in ∼40%.84 The therapeutic relevance of this pathway, however, remains unclear because it is unknown whether the intracellular (and thus effector) domain is expressed in GEP-NEN.85

In contrast with the delineation of the positive regulators of NEN proliferation, the inhibitors have been well characterized, particularly the analogs that target somatostatin receptors. Somatostatin-receptor activation has been linked to at least four different inhibitory effects.86 These include 1) inhibition of adenyl cyclase, with a subsequent decrease in intracellular cAMP resulting in down-regulation of PKA; 2) activation of K+ and Ca2+ channels, leading to inhibition of transmembrane Ca2+ influx and resulting in a reduction of intracellular Ca2+; 3) activation of protein phosphatases (eg, calcineurin), which inhibit the exocytosis and serine/threonine phosphatases that influence Ca2+ and K+ channels; and 4) activation of intracellular tyrosine phosphatases, which, through different pathways, inhibits proliferation. Somatostatin has been noted in in vitro systems to affect the activity of phospholipase C, cyclic guanosine 3′,5′-monophosphate, and phospholipase A2.87 However, it remains unclear whether somatostatin is directly antiproliferative or acts through inhibition of growth factors and/or various trophic hormones such as growth hormone, IGF-I, insulin, gastrin, or epidermal growth factor from both the neoplastic cell and the surrounding tumor matrix.88 Nevertheless, irrespective of the mechanism, the clinical data provide some support for a role for this biotherapy as a negative regulator of GEP-NEN proliferation.28, 29

Intracellular Signaling Pathways

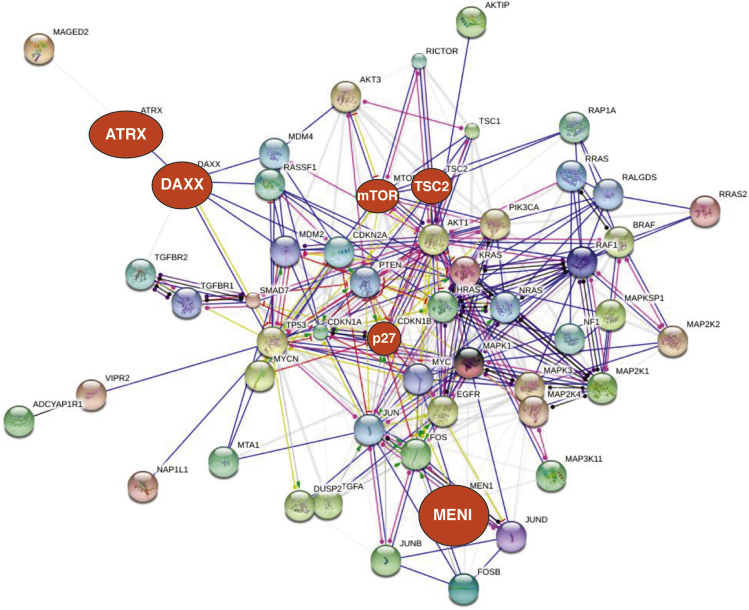

GEP-NEN exhibit three major signaling pathways: Ras/Raf/MAPK, PKC, and PI3K/protein kinase B (Akt) with some participation of Notch signaling89, 90 and Gli/Hedgehog/SNAIL and Src kinases (Figure 4).91, 92, 93 The Ras/Raf/MAPK and PKC pathways signal growth factor responses (eg, tyrosine kinase receptor activators), typically from stimulatory factors such as gastrin. PI3K/Akt regulates the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) complexes, which are regarded as master switches regulating cell fate and are considered to be principal regulators of cell proliferation and angiogenesis.94 As an intracellular protein, mTOR plays a central role in cell growth, protein synthesis, and autophagy by integration of input from multiple upstream pathways (insulin, growth factors [IGF-I/IGF-2]), and mitogens. In addition, mTOR also functions as a sensor of cellular nutrient and energy levels as well as the redox status.94

Figure 4.

Protein interactome involved in neuroendocrine neoplasm proliferation.Proliferative signaling includes a tightly regulated signaling interactome (including RAS/RAF, MAPK, and PI3K/Akt). The number and extent of linkages illustrates the potential for pathway cross-activation and redundancy in signaling. CCND1 (cyclin D1) represents a nexus focus involved in regulation of G1/S transition during the cell cycle. Known mutations in the interactome are identified (red); the size being reflective of the frequency of mutations (ie, MEN1/ATRX/DAXX mutations occur in 40%–50%, mTOR ∼15%, P27KIP1 ∼10%). These are largely peripherally localized (except for P27, regulator of G1 progression), which is consistent with their known tumor-suppressor function. Targeting the somatostatin receptor family has clinical utility as an antiproliferative strategy, but there is no direct link between these receptors and proliferative signaling pathways. Because these somatostatin receptors interact with protein kinase C, this may provide a potential link by indirect inhibition of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling. Current data renders it unlikely that somatostatin inhibitory effects are transduced via proliferative signaling inhibition. Created with protein/transcripts identified in neuroendocrine neoplasms and String 9.1.213

Two key pathways, the MAPK and PI3K/Akt pathways, are of considerable relevance in non-NEN lesions. They often exhibit activating mutations, usually due to constitutive activation of MAPK such as through gene-encoding serine/threonine-protein kinase B-Raf (BRAF) mutations such as V600E and/or through loss of an inhibitory factor such as phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN) in the Akt pathway.95 There is also significant cross-talk between the MAPK and Akt pathways, and activation or inhibition in one pathway may cause signal alteration in a second pathway. This is reflected in the inadvertent therapeutic consequence of drug resistance consequent to overactivation of compensatory pathways.96, 97 By contrast, although NEN themselves do not express common growth regulatory pathway mutations in MAPK and PI3K/Akt (discussed in the next section), they exhibit abnormalities (altered expression levels) in both pathways.

The RAS/RAF/MAPK signaling pathway is usually activated,98, 99 and expression of the BRAF activator Rap1 as well as B-Raf itself can be detected by immunohistochemical analysis (75%).100 In intestinal NEN, mutations in KRAS upstream of MAPK were identified in 3 of 102 neoplasms (∼3%).84 The relationship to signaling was not evaluated. Evidence for mTOR signaling is provided by observations that PTEN expression has been noted in carcinoids (low/middle grade NEN) whereas neuroendocrine carcinomas exhibited low or no PTEN activity (PTEN absent in ∼50%).101 This is reflected by the observation that Akt is phosphorylated (activated) in 76% of NEN.102 The mechanisms leading to these alterations are unknown but probably reflect the chromosomal losses (usually chromosome 18q but also alterations in 10q and 14q, sites of PTEN and Akt, respectively) that have been identified (60%–80%) in NEN.1

In much the same way that the secretome can be visualized, our current understanding of the NEN proliferome recognizes that it comprises a tightly regulated signaling interactome with significant cross-linkages consistent with the potential for pathway cross-activation and redundancy in signaling (Figure 4). A particular nexus of the system is provided by CCND1 (cyclin D1), which is involved in the regulation of the G1/S transition during the cell cycle. Known mutations in the interactome are largely peripherally localized (except for P27, regulator of the G1 progression), which is consistent with their known tumor suppressor function. Although targeting the somatostatin receptor family has clinical utility as an antiproliferative strategy, there is no direct link between these receptors and proliferative signaling pathways. Because these receptors interact with PKC, this may, however, provide a potential link by indirect inhibition of MAPK signaling.

The Landscape of Neoplastic Transformation

GEP-NEN appear to be derived from stem cell–derived local tissue-specific neuroendocrine cells of the gastrointestinal tract and pancreas. The former evolve from a committed precursor cell within intestinal crypts103 or in the pancreatic ductal epithelium.104 Transcription factors involved in regulating the neuroendocrine phenotype, such as PAX genes and neurogenin 3 (NGN3), are not considered to play a role in the evolution of NEN.

The Knudson hypothesis, which is well accepted for non-NEN disease, proposes that neoplasms arise as a result of an acquired genomic instability and the subsequent evolution of tumor cells with variable patterns of selected and background aberrations.105 These observations were based upon a comparison of age-specific incidence curves between inherited and noninherited cases of retinoblastoma. The former exhibited an increased incidence by an amount consistent with the advance of progression by one rate-limiting step. This provided a method of analysis by which quantitative comparisons of age-specific incidences between two groups could be used to infer the underlying processes of progression. Such a comparison identified a genetic mutation as a key rate-limiting step. Proto-oncogenes (eg, genes regulating cellular proliferation) increase the probability of cancer when activated,106 but carcinogenesis generally requires that mechanisms of DNA repair, such as tumor suppressor genes, are also inactivated.105, 107 Numerous activating mutations (eg, BRAF V60E) have been identified (see: http://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cancergenome/projects/cosmic/). Tumor-suppressor genes have also been identified, but these are fewer in number. Modeling of cancer-gene activation and studies of the evolution of cellular defense mechanisms have determined that oncogenes may be frequently activated first within populations of large organisms, with tumor-suppressor gene inactivation as a second step before cellular deregulation and tumor emergence.108 This conforms to the classic cancer paradigm.

Unlike in the majority of cancers, activating mutations are infrequent if not largely unknown in GEP-NEN (Figure 5). Indeed, most neuroendocrine neoplasms of the small and large intestines arise in a sporadic manner. Others, notably ECL cell neoplasms of the stomach, are associated with ECL cell hyperplasia, usually due to hypergastrinemia. Gastrin-containing G-cell neoplasms and somatostatin-secreting D-cell neoplasms of the duodenum as well as pancreatic NEN are associated with MEN-1–related neuroendocrine cell neoplasia.109 The latter may not reflect transformation of islets and instead may be derived from pluripotent cells in the ductal/acinar system.110

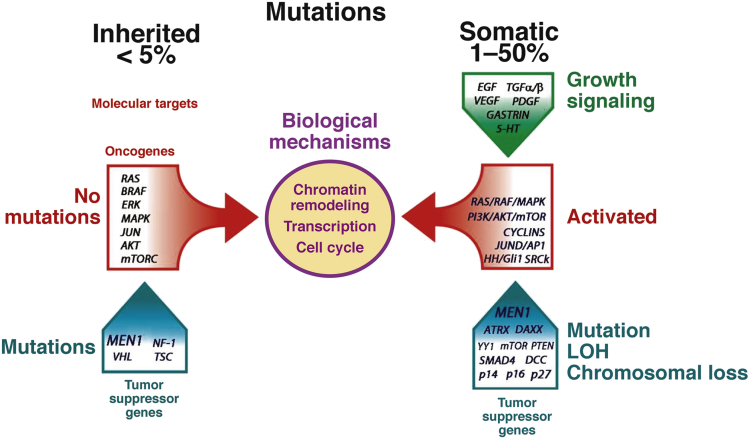

Figure 5.

Inherited mutations have only been identified in tumor-suppressor genes (TSGs), and occur in <5% of all gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms (GEP-NEN). Although no activating mutations have been identified in the molecular targets (eg, RAS or BRAF), the biologic results of TSG loss (chromatin and transcriptional alterations as well as changes in cell cycle regulation) are a consequence of alterations signaled by these oncogenes. The second “hit” under these conditions remains to be identified. Somatic alterations are more common and have been variably identified in 1%–50% of GEP-NEN. These typically involve mutations, loss of heterozygosity (LOH), and chromosomal changes (eg, telomeric or instabilities) that result in activated signaling pathways including RAS/RAF/MAPK, PI3K/Akt/mTOR, Src kinases, or histone modifications. They exhibit similar biologic consequences as inherited mutations. The growth regulatory milieu and proproliferative signaling, such as through growth factors, likely contribute to tumor development. Molecular alterations at a DNA level remain undefined in ∼50% of tumors.

Pancreatic NEN Molecular Events

Apart from inherited neoplasms—those that exhibit germ-line mutations in MEN-1 (discussed in detail in the section Menin Mechanisms and Metastases)—little is known of the molecular basis for oncogenesis or of the progression of sporadic pancreatic NEN (the majority).111 Standard mutations in k-ras, P53, myc, fos, jun, src, and the Rb gene have not been specifically implicated.112, 113 K-ras, paradoxically, has been implicated in the suppression rather than the promotion of pancreatic endocrine cells through Ras association (Ral/GDS-AF-6) domain family member 1 (RASSF1A) and blockade of the RAS-activated proproliferative RAF/MAPK pathway by menin.114 Loss of heterozygosity (LOH) at the MEN1 locus (eg, 11p13q) remains the commonest alteration in pancreatic NEN, and whole exome sequencing has not identified any novel gene activator mutations. Spontaneous mutations in tumor-suppressor genes—MEN1 (∼50%), alpha thalassemia/mental retardation syndrome X-linked (ATRX, 18%), death-domain associated protein (DAXX, 25%), and to a far lesser extent, mTOR (15%)—have been identified.115 Gene knockout/knock-in studies confirm the relevance of MEN-1 whereby inactivation uncouples the endocrine cell cycle progression from environmental cues such as glucose, leading to islet cell proliferation.116 Both ATRX and DAXX (which both encode proteins involved in chromatin remodeling) are somatically mutated in ∼40% of pancreatic NEN and are associated with activation of alternative lengthening of telomeres. In addition, decreased expression (and, by inference, function) is associated with chromosome instability and correlates with tumor stage and metastasis, a reduced time of relapse-free survival, and a decrease in survival.117 More recently, a recurrent somatic mutation in YY1 (T372R) was noted in ∼30% of sporadic insulinomas.118 YY1 is a member of the GLI-Kruppel class of zinc finger transcriptional repressors linked to mTOR signaling and histone modification.119 Clinically, the T372R mutation is associated with a later onset of tumors.118

Molecular and cytogenetic analyses have identified a number of chromosomal alterations in pancreatic NEN. Comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) studies indicate chromosomal losses occur more frequently than gains, while amplifications are uncommon.120, 121 The total number of genomic changes per tumor appears linked to tumor volume (size) and disease stage, indicating that genetic alterations accumulate during the natural history of the lesion. Thus, large neoplasms with increased malignant potential—and especially metastases—tend to harbor more genetic alterations than the small and clinically benign neoplasms. This suggests that a loss of tumor-suppressor pathway(s) and genomic instability represent mechanisms associated with progression but not initiation of pancreatic NEN. Losses of chromosomes 1 and 11q as well as gains on 9q are, however, early events because they have been identified in small neoplasms. Prevalent chromosomal alterations common in metastases include gains of both chromosome 4 and 7 and losses of 21q, implying that these chromosome imbalances may contribute to tumor metastasis.122, 123 The relevant genes (and pathways) have not yet been elucidated.

Deletions of 9p, which occur in ∼30% of pancreatic NEN, include the P16INK4A and P14ARF genes, both of which encode tumor suppressors; loss of this gene locus may lead to tumorigenesis due to deregulation of the P53 and cyclin D1/Rb pathways. Alterations in the cyclin D1 pathway in pancreatic NEN indicate overexpression of this proto-oncogene in 43% of neoplasms.124 Chromosome 16p, which contains TSC2 (tuberous sclerosis complex 2 [tuberin], a tumor suppressor of the Akt/mTOR pathway with GTPase-activating function), is lost in ∼40% of pancreatic endocrine tumors,122, 125 whereas PTEN a second tumor suppressor at this locus, is lost in 10% to 29% of lesions.122, 125, 126 Low expression of either TSC2 or PTEN correlates with pancreatic NEN aggressiveness, a “nonfunctional” status, liver metastasis at diagnosis or follow-up evaluation, and the proliferation index score and time to progression.127 This supports involvement of the Akt/mTOR pathway in pancreatic NEN tumorigenesis and progression. Pancreatic NEN also overexpress the mouse double-minute genes (now MDM oncogene, E3 ubiquitin protein ligase) MDM2 and MDM4, and protein phosphatase 1D (PPM1D/WIP1), all of which may attenuate the function of P53. Because P53 is critical in maintaining genomic stability, alterations in regulators of P53 are considered to play a permissive role in pancreatic NEN pathogenesis.128 One report documents a 100% association of X-chromosome deletions with pancreatic NEN.129 Two studies of pancreatic NEN found no evidence of microsatellite instability (MSI).130, 131

Small Intestinal NEN Molecular Events

DNA sequencing of small intestinal NEN failed to identify mutations in MEN1, DAXX, or ATRX and identified small intestinal NEN as one of the most genomically stable cancers thus far analyzed.132, 133 Point mutations (single-nucleotide variants, SNVs) were barely detectable at an average rate of 0.1 SNV per 106 nucleotides (range: 0–0.59).132 MSI, a common feature of small intestinal adenocarcinomas,134 is uncommon in small intestinal NEN.130, 131, 135 Eight percent of small intestinal NEN exhibit small insertions or deletions that can inactivate the cell-cycle inhibitor CDKN1B or P27KIP1.133 An evaluation of GEP-NEN identified that menin or P27-negative neoplasms (as opposed to menin/P27-dual-positive) were associated with a high histologic grade, lymph node metastasis, and a more advanced stage in foregut and small intestinal NEN. P27 loss was significantly associated with a decreased survival and was an independent factor for poor overall survival. P27 is implicated in the MEN4 syndrome,136 and it is transcriptionally regulated by menin,137 suggesting that the mechanistic basis for pancreatic NEN and small intestinal NEN may be coupled at a molecular level.

Somatic SNVs have been identified in 197 genes with a preponderance of cancer genes in small intestinal NEN, including FGFR2, MEN1, HOOK3, EZH2, MLF1, CARD11, VHL, NONO, FANCD2, and BRAF.132 Whether these SNVs have functional implications or reflect noninformative, biologically silent SNPs is unknown. The absence of canonical cancer mutations is supported by a limited study that used CancerCode to identify tumor-specific mutations.138

CGH has identified gains in chromosomes 17q and 19p (57%) and in 19q and 4q (50%)139 as well as in 4p (43%), 5 (36%), and 20q (36%). Chromosomal losses were noted in 18q or 18p (43%), and 21% had full or partial loss of 9p.139 Of 14 neoplasms, six had a full gain of chromosome 4, of which four samples also had a gain of chromosome 5. There were four neoplasms with a gain of chromosome 4 along with a partial or full trisomy of chromosome 14.139 In a separate CGH study, losses in 18q22-qter (terminal end of chromosome 18q) (67%) and 11q22–23 (33%) were the most common genetic defects, although losses of 16q (22%) and gains of 4p (22%) were also identified.140

Because 18q and 11q chromosomal losses have the highest frequency, they may reflect early events in small intestinal NEN tumorigenesis. Losses on chromosome 16 and gain-of-function on chromosome 4 are later events in tumor/carcinoid development. This is supported by a report that aberrations in 16q and 4p tend to occur in metastases.141 Lollgen et al142 confirmed that 18q deletions were characteristic of midgut NEN; losses were detected in 88%. These findings have been confirmed in more recent reports.143, 144

One of the genes encoded on chromosome 18 (18q21) is the tumor suppressor gene DCC (deleted in colorectal carcinoma). Loss of this gene, which has been linked to the tumor suppressor NCAM (neural cell adhesion molecule on 11q145), is thought to play a role in carcinoid genesis.146 A 40-kb heterozygous deletion in chromosome 18q22.1 has been suggested as a potential inherited factor, but the low occurrence (∼6%) makes it difficult to appreciate the significance.147 A gain of chromosome 14 has been identified as a marker of poor prognosis,143 whereas the antiapoptotic protein DAD1 (defender against cell death) has been identified in one of the chromosome 14 foci, and confirmed (via immunohistochemistry) to be overexpressed.144

Another CGH study identified that ∼20% of small intestinal NEN exhibited alterations in the distal part of 11q (location of succinate ubiquinone oxidoreductase subunit D gene, SDHD).141 Furthermore, two of five small intestinal NEN had a missense mutation in the SDHD gene in association with LOH of the other allele, suggesting that alterations in this gene may be implicated in tumorigenesis.141 An analysis of MSI in well-differentiated small intestinal NEN or their metastases using the BAT-26 microsatellite locus in intron 5 of hMSH2 and the BAT-II microsatellite region of TGFβRII135 identified no evidence for mismatch repair-related instability. In contrast, carcinomas of the small intestine exhibit MSI in ∼20% of cases,148, 149 suggesting that NEN evolve differently than epithelial neoplasia in this organ.135 The latter exhibited high frequencies of activating BRAF/KRAS mutations, which are typically absent in NEN.134

The Promised Land of Transcriptional Profiling

Transcriptional profiling of both pancreatic and small intestinal NEN has demonstrated that both are characterized by nonoverlapping expression of transcripts both between and within each tumor group (heterogeneity of expression).

Pancreatic NEN

A study of nine core biopsies (normal pancreas, pancreatitis, pancreatic adenocarcinoma, pancreatic adenocarcinoma metastases, and pancreatic NEN) identified pancreatic NEN as expressing a series of genes including ANG2 (overexpressed in 89%).150 In addition, islet amyloid protein and calcitonin signaling were two pathways expressed. An assessment of 24 pancreatic NEN (including 50% insulinomas) using U133A Affymetrix (Santa Clara, CA) arrays identified two subtypes of pancreatic neoplasia: benign and malignant. The latter overlapped with the World Health Organization category of “well-differentiated endocrine carcinoma” and was characterized by an overexpression of FEV, adenylate cyclase 2 (ADCY2), nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 2 (NR4A2), and growth arrest and DNA-damage-inducible β (GADD45β).151 Platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) was also expressed, and phosphorylation of PDGFR-β was observed in 83% of all neoplasms. Signal pathway analysis identified β-catenin, cadherin, and DNA damage as critical elements. Seventy-two primary pancreatic NENs, seven matched metastases, and 10 normal pancreatic samples were examined using the 18.5 K human oligo microarray from the Ohio State University Cancer Center.127 A plethora of transcript alterations were identified, but focus was directed to the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. TSC2 and PTEN were down-regulated in most (∼80%) of the primary tumors, and this decreased expression was associated with shorter disease-free and overall survival. In addition, they identified that transcript levels of somatostatin receptor 2 (sst2) were absent or low, particularly in insulinomas versus nonfunctioning neoplasia, and that expression of fibroblast growth factor 13 (FGF13) was associated with liver metastasis and shorter disease-free survival.120 In addition, signaling abnormalities were noted in catenin/cadherin pathways as well as in Akt signaling, while recessive disease-associations included PI3KR1 and RB1 in pancreatic NEN.

Small Intestine

Affymetrix transcriptional profiling identified >1,500 overexpressed and ∼400 transcripts that are decreased in expression in a group (∼30 samples) of small intestinal NEN.152 Further analysis identified three potentially useful malignancy-marker genes. Specifically, overexpression of nucleosome assembly protein-like 1 (NAP1L1), melanoma-associated antigen D2 (MAGE-D2), and MTA1 mRNA and MTA1 protein in tumor and metastatic small intestinal NEN was confirmed. These genes may be markers for identifying metastatic tumors, and NAP1L1 may be a neuroendocrine tumor-specific marker.152 Overexpression of MTA1 has been confirmed,153 and expression of these markers is effective in the prediction of small intestinal NEN grade and stage.154 Other candidate marker genes have been identified in small intestinal carcinomas,155 including paraneoplastic antigen Ma2 (PNMA2), testican-1 precursor (SPOCK1), serpin A10 (SERPINA10), glutamate receptor ionotropic AMPA 2 (GRIA2), G protein-coupled receptor 112 (GPR112), and olfactory receptor family 51 subfamily E member 1 (OR51E1). Further assessment of PNMA2 identified elevated protein levels, particularly in the blood, and titers were sensitive, specific, and superior to CgA measurement for the risk of recurrence after small intestinal NEN resection.156

A separate gene expression study identified that primary tumors and lymph node metastases in 19 patients differed in expression profiles, suggesting evidence for genetic change during metastasis.157 Genes identified in neoplastic progression included actin γ2 (ACTG2), gremlin 2 (GREM2), regenerating islet-derived protein 3α (REG3A), tumor suppressor candidate 2 (TUSC2), runt-related transcription factor 1 (RUNX1), tryptophan hydroxylase 1 (TPH1), transforming growth factor-β receptor, type II (TGFBR2), and cadherin 6 (CDH6). The functional role of TGFβRII has been confirmed in NEN.135

Small intestinal NEN also exhibit a distinctive gene expression profile compared with pancreatic neoplasia, and transcriptional profiling has also identified up-regulation of extracellular matrix protein 1 (ECM), VMAT1, galectin 4 (LGALS4), and RET proto-oncogene (RET).151 A reanalysis of two publicly available small intestinal tumor transcriptomes (Yale and Uppsala) using network-based approaches identified the existence of two potentially different small intestinal NEN types: one group that principally synthesizes and secretes 5-HT and a second that expresses serotonin, substance P, and other tachykinins.158 The integrated cellular transcriptomic analyses confirmed the expression of core secretory regulatory elements such as carboxypeptidase E (CPE), proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 1 (PCSK1), secretogranins, including genes involved in depolarization such as neuronal specific protein channel 3 (SCN3A), and transcription factors associated with neurodevelopment (NKX2-2, NeuroD1, INSM1) and glucose homeostasis (amyloid β [A4] precursor-like protein 1, APLP1). These neoplasia were regulated at a developmental level, and they expressed activation of hypoxic pathways (a known regulator of malignant stem cell phenotypes) and genes involved in apoptosis and proliferation. Further analyses (genomewide coexpression) identified that the small intestinal NEN gene network was nonrandom, scale free, and highly modular. Based on the mathematical appreciation of these parameters, it was inferred that the biologically informative organizing principles could be assessed.159 The superimposition of functional analysis confirmed that processes including nervous system development, immune response, and cell cycle were expressed in the network. In addition, it was apparent that substantial overexpression of GPCR signaling regulators was evident. The significance of the expression of neural GPCRs is their key role in the differential activation of CRE targets associated with proliferation and secretion.

Global micro-RNA (miR) profiles of pancreatic and small intestinal NEN reveal nonoverlapping expression of regulators both between and within each NEN type, similar to transcriptome analysis.160, 161, 162, 163 In pancreatic NEN, up-regulation of miR-103 and miR-107 was identified,160 and miR-21 overexpression was associated with both high proliferation and liver metastases.160 In contrast, a separate study reported that expression of miR-642 correlated with proliferation, and miR-210 was associated with metastatic disease.161 Li et al162 independently noted that down-regulation of serum miR-1290 discriminated pancreatic NEN from adenocarcinomas. In small intestinal NEN, five miRNA including miR-96, miR-182, miR-183, miR-196, and miR-200 were up-regulated during tumor progression, whereas four (miR-31, miR-129–5p, miR-133a, and miR-215) were significantly down-regulated.163 The cardiac-specific miRNA-133a has been confirmed to be down-regulated in metastases,164 but the relevance of this observation remains to be determined. It is likely that network-based approaches may have more utility for identifying relevant miRNAs as well as determining biologically useful interactions that have potential clinical relevance.

Menin Mechanisms and Metastases

Pancreatic NEN

Pancreatic NEN are typically more aggressive than other GEP-NEN. This likely reflects the mutational spectrum: MEN-1, ATRX, and DAXX are identified in ∼50% of lesions. It is noteworthy that all the genes linked to inherited syndromes in pancreatic NEN are tumor-suppressor genes; none are oncogenes. The single gene confirmed as mutated in small intestinal NEN (<10%), P27KIP1, is also a tumor-suppressor gene. To date, no inherited genetic factors are known; however, sporadic reports of familial relationships suggest that genetic factors remain to be identified.165

The MEN1 gene is located on the long arm of chromosome 11, band q13.166 Tumorigenesis likely involves loss of function of this growth-suppressor gene,105 and it is considered to follow a two-step process: a germline mutation affecting the first MEN1 allele, and a second somatic inactivation of the unaffected allele (LOH). Menin, a 610-amino acid nuclear protein encoded by the MEN1 gene, interacts with Jun D and the activator protein-1 (AP-1) transcription factors to modify growth-regulatory signaling. It also networks with nm23H1/nucleoside diphosphate kinase (nm23), and exerts GTPase activity.167 This gene product is also linked to TGFβ signaling (through SMADs),168 RAS-RAF signaling,114 and Gli1/hedgehog signaling169 as well as to histone modification (with transcriptional regulation of a plethora of genes).170 Its association with a histone methyltransferase complex containing, MLL2 results in differential methylation of histone H3 on lysine 4, and its association with RNA polymerase II is linked to the regulation of Hox expression.171

Menin likely functions as a neuroendocrine nexus gene (a master regulator)172 that controls cell signaling as well as gene expression, including differentiation-regulating genes in pancreatic NEN. As a classic tumor suppressor, a second hit is required for tumorigenesis (often considered as LOH). As previously noted, an inherited MEN-1 mutation results in pancreatic NEN and the development of gastric carcinoids, particularly if trophic hormones such as gastrin are elevated (eg, in Zollinger-Ellison syndrome). It is enigmatic that the same inherited mutation is not associated with the synchronous development of neuroendocrine neoplasia in the small intestine or other gut sites. The mechanisms that regulate the penetrance of the MEN1 gene are unknown.

Three other inherited NEN gene disorders include those of the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor (VHL), nuclear factor 1 (NF-1), and the tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) family. VHL173 interacts with the elongin family of proteins to regulate transcriptional elongation174 and may play a role in hypoxia-induced cell regulation and extracellular matrix fibronectin expression and localization.175 Mutations in NF-1 result in down-regulation of the P21ras signaling pathway, which leads to a constitutively activated guanosine triphosphate (GTP) (similar to menin) culminating in abnormal cell proliferation.176 The TSC genes, hamartin (TSC1), and tuberin (TSC2), play a role in the PI3K/Akt pathway, in cell adhesion (glycogen synthase kinase 3 pathway), and in proliferation (MAPK pathway).177

Small Intestinal NEN

An inherited disposition for small intestinal NEN has yet to be published; however, families who have multiple kindreds with the disease (eg, see http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT00646022) have been identified, and candidate genes are being sought. Genetic analyses of a family with three consecutive first-degree relatives failed to identify an inherited MEN-1 predisposition.165 Similar studies,178, 179 indicate that the menin gene is not linked to inherited tumors of the small intestine.

Additional support for an inherited factor has been provided by family cancer studies. The Swedish Family Cancer database study identified an increased risk of small intestinal NEN in the progeny of patients with squamous cell skin cancer (relative risk 1.79), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (relative risk 2.06), and endometrial cancer (relative risk 2.21).180 The children of patients with small intestinal NEN had an increased risk of cancer of the breast (relative risk 1.39), kidney (relative risk 2.08), and brain (relative risk 1.65). This and other epidemiologic-based studies180, 181 have suggested that an increased risk of developing small intestinal NEN occurs in individuals who have a parental history of the disease, and that a family history of any cancer (ie, not only NEN) is a risk factor for the development of these neoplasia.182 The mutations linked to small intestinal NEN disease development remain unknown.

Metastases

NEN metastatic disease remains a conundrum, despite the fact that the majority of GEP-NEN have distant spread when diagnosed.1 It is unclear why in the almost complete absence of known cancer-causing mutations as well as the relatively low proliferative potential of tumors (>60% small intestinal NEN are low grade [<2% proliferating index]), most tumors are metastatic. Evidence for this is based on a series of epidemiologic studies. Typically, 12% of GEP-NEN <10 mm have already metastasized at the time of diagnosis, and 60% of lesions <20 mm are metastatic.8 This is particularly relevant for small intestinal and colonic NEN, where ∼90% were already metastatic at 20 mm in size. It is noteworthy that 72% of small intestinal NEN are already metastatic when the primary is only 10 mm in size.8 Thus, metastasis occurs despite “indolence” and is not reflected in survival (there is no statistically significant difference in survival between localized and metastatic disease with small intestinal NEN: 94% and 80%, respectively).8 The long-accepted adage that there is a direct relationship between size and the development of metastases thus does not appear to apply to GEP-NEN. Currently, the basic mechanisms that drive metastasis (like those that drive tumorigenesis) remain ill-defined; however, two genes, ATM and MTA1, have been implicated.

Ataxia telangiectasia mutated kinase (ATM) gene

The ataxia telangiectasia mutated kinase (ATM) gene is the causal gene of Ataxia-telangiectasia and is involved in the regulation of DNA damage responses; hyperactivation of ATM is associated with increased metastasis through overexpression of epithelial-mesenchymal markers like SNAIL.183 A study of colorectal NEN (n = 31) using polymerase chain reaction arrays noted that high ATM mRNA levels were strongly correlated with overexpression of ATM protein by immunohistochemistry and low-proliferation rates.184 ATM-negativity was also associated with significantly decreased overall survival. This was confirmed both in an independent validation set (20 metastatic and 18 non-metastatic GEP-NEN, including pancreas and rectum) where a decreased ATM transcript were associated with metastasis. In a subsequent pancreatic NEN study (n = 107), high ATM expression was associated with a significantly smaller tumor size, lower recurrence rate, and well-differentiated tumors.185 Overall, ATM down-regulation was associated with metastases184; the mechanism, however, appears to differ from non-neuroendocrine neoplasia such as breast cancer, where hyperactivity not loss of activity is mechanistically linked to metastasis.183

Metastasis-associated 1 gene (MTA1)

Metastasis-associated 1 gene (MTA1) is an important component of the nucleosome remodeling and histone deacetylase (NuRD) complex, and it plays a role in DNA repair, inflammation, and pathogen-driven pathologic conditions.186 MTA1 was initially identified by transcriptional profiling to be overexpressed in small intestinal NEN,152 and subsequent functional studies identified up-regulation by TGF-β which also induced gene responses associated with growth promotion (c-Myc and the ERK pathway) and invasion (E-cadherin).80 MTA1 has more recently been reported as overexpressed in the majority (>95%) of small intestinal NEN, suggesting that this gene may activate the molecular pathway(s) promoting tumor progression and metastasis development.187 Mathematical modeling demonstrates that tumor expression levels (mRNA) of MTA1 can be used to predict metastases with 100% sensitivity and specificity.154

Clinical Utility

The application of molecular information about NEN to provide added clinical utility in GEP-NEN treatment can be applied to three areas: functional imaging, the application of transcriptomic technologies to diagnosis, and the identification of drug targets.

Identification of Functional Imaging Targets

Imaging has a central role in the diagnosis, staging, treatment selection, and follow-up evaluation of GEP-NEN. In this respect, nuclear medicine or functional techniques, particularly positron emission tomography (PET), exhibit optimal diagnostic sensitivity for these lesions.1 They are usually combined with a fusion of anatomic techniques to maximize the acquisition of clinically relevant spatial information.188

The utility of these approaches is mostly based on targeting somatostatin receptors (>80% of lesions189, 190) and through leveraging the canonical amine precursor uptake and decarboxylation (APUD) features of these lesions. Nuclear medicine imaging consists of conventional scintigraphy typically undertaken with somatostatin analogs (SSA) such as 111In-pentetreotide (or OctreoScan), or 99mTc-labeled analogues such as 99mTc-HYNIC-TOC) and PET/computed tomography. PET techniques mainly use 68Ga-DOTA-SSA peptides (DOTA-NOC, -TOC, and -TATE). Alternative PET techniques employ amine precursors such as 18F-DOPA and 11C-5-hydroxytryptophan.191

The utility of this approach is based on one of the fundamental properties of peptide-secreting neuroendocrine cells initially identified by Pearse in 1966.192 In principle, this embodies active amino acid uptake (via large amino acid transporters [LATs]193) as well as amine transportation across the vesicular membrane, which is undertaken by transporters that are proton-coupled antiporters.194 This coupling of intracellular transport with vesicular accumulation forms the basis for tracer accumulation and imaging (eg, 11C-5-HTP, 18F-DOP, and 123I-MIBG) of neoplastic cells.193, 195 Identification of novel transporters and metabolic molecules will lead to the development of additional strategies for defining tumor function.

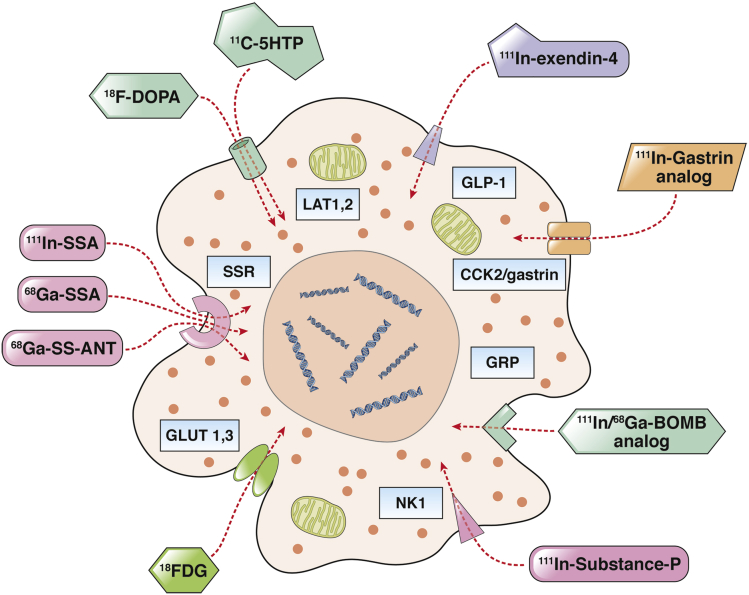

Radiolabeled SSAs are mostly used because of their theranostic properties, namely, the capacity of the same receptor peptide of being used for imaging or therapy by simply switching the radioisotope.196, 197, 198 It seems probable that by using a molecular-based search strategy other G-protein receptor peptides will be identified for clinical study. In addition, the recognition of pathways that can be imaged such as has been undertaken with increased glucose metabolism, expressed as 18F-FDG uptake, can be used to define the prognosis199 (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Functional imaging of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms (GEP-NEN) using radiolabeled ligands. Radiolabeled somatostatin analogs (SSAs) are the most exploited. Scintigraphy with 111In-pentretreotide and, more recently, positron emission tomography (PET)/computed tomography techniques with 68Ga-SSA target somatostatin receptors (SSR) are regarded as the optimal nuclear medicine NEN imaging tools. Alternative PET techniques with amine precursors such as 18F-DOPA and 11C-5HTP have also been shown to be sensitive modalities. Experimental techniques include the use of SSR antagonists, GLP-1, GRP, and NK ligands. BOMB, bombesin; 11C-5HTP, 11C-hydroxy-tryptophan; 18FDG, 18F-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose; 18F-DOPA, 18F-fFuoro-lL-DOPA; 68Ga-SSA: 68Ga-DOTATOC, 68Ga-DOTANOC, 68Ga-DOTATATE; 68Ga-SS-ANT, 68Ga-labeled SSR antagonists; GLP-1, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor; GLUT-1,3, glucose transporter type 1 and 3; GRP, gastrin-releasing peptide receptor; 111In-SSA: 111In-Pentetreotide, 111In-Depreotide, 99mTc-EDDA-HYNIC-Tyr3-octreotide; LAT 1,2, large neutral amino acid transporter type 1 and 2; NK1, neurokinin 1 receptor; SSR, somatostatin receptor.

Identification of Drug Targets

Current molecular approaches have failed to identify uniformly expressed novel, targetable DNA sequences in NEN. Although a role for the mTOR pathway has been suggested, mutations in only a small proportion of NEN (∼15% pancreatic NEN) suggest this may be a limited target. It remains unclear in what settings mTOR inhibitors would work.200 It does, however, raise the possibility of menin as a candidate target. Menin is the most commonly altered gene locus in GEP-NEN (∼50% of pancreatic NEN as well as gastric carcinoids) and its interaction with P27 signaling (mutated in small intestinal NEN) suggests it may provide a common target that encompasses both tumor types.

Because the menin crystal structure is available, progress has been made in the development of potent small-molecule and peptidomimetic inhibitors of the gene product.201 However, the majority of studies have focused on the role of menin as an essential cofactor in oncogenic mixed-lineage leukemia (MLL) fusion proteins and the development of targets to treat acute leukemia. Menin-targeting drugs are challenging chemical problems, given the difficulties in elucidating the mechanism by which menin binds to protein effectors and given its complex bivalent mode of engagement.202 Although there is the rationale for targeting this gene and its pathways, clinical utility will require the design of next generation of inhibitors for effective targeting in GEP-NEN.

The TGF-β pathway is also linked to menin (TGF-β/SMAD signaling is altered in ∼25% of small intestinal NEN), and targeting this area may provide an alternative approach. Several agents (eg, SD-208 [2-(5-chloro-2-fluorophenyl)-4-[(4-pyridyl)amino]p-teridine]) have been developed that target receptor kinase activity and limit tumor invasion and metastasis in pancreatic adenocarcinoma and melanoma models.203 Because no clinical data are currently available, it remains to be seen whether they could be effective in GEP-NEN.

Translational Transcriptomics and Network Neologies

Tumor transcriptomes contain information of critical value to understanding the different capacities of a cell at both a physiologic and pathologic level. In terms of clinical relevance, they provide information regarding the cellular toolkit—the pathways associated with malignancy and metastasis or drug dependency. Exploration of this resource thus can be leveraged as a translational tool to better manage and assess neoplastic behavior.

Multiple genes or gene products have been identified that could provide therapeutic targets (eg, FEV or MTA1) to be used as biomarker measurements or to assess tumor biology or identify new targets (network-targeted approach).204, 205 Gene-expression profiling and supervised machine learning of marker panels of implicated in tumorigenicity, metastasis, and hormone production have successfully been used to classify small intestinal NEN subtypes and can accurately (100%) predict metastasis.154

Because peripheral blood is more accessible for gene testing than tissue, a polymerase chain reaction approach has been used to identify circulating NEN markers. Circulating tumor mRNA can be detected in plasma, and a combination of expression and measurements of circulating NEN-related hormones and growth factors has provided high sensitivity and specificity to diagnose small intestinal NEN (81.2% and 100%, respectively).206 The NETest (Wren Laboratories, Branford, CT), a more recent multianalyte algorithmic analysis, includes 51 marker genes, exhibits high sensitivity (>95%) and specificity (>95%) for the detection of GEP-NEN, and provides a multidimensional (gene cluster analysis) assessment of disease status.207, 208 Multianalyte algorithmic analysis strategies of this type are significantly more accurate than CgA and pancreastatin209, 210, 211, 212 and are not affected by proton pump inhibitor usage.212

Conclusion

GEP-NEN represent a diverse group of neoplasia that exhibit a unique pathobiology and a neoplastic molecular profile that is substantially different from other epithelial cancers. Traditional DNA sequencing approaches to investigating the molecular basis of NEN disease have, to date, yielded relatively little information (with the exception of pancreatic NEN). Consequently, one important question is to characterize what constitutes the driver of neoplastic development. This may involve a focus on noncoding or long-chain RNA, a better delineation of the epigenome (and how it is regulated), or an identification of the environmental trigger that leads to a neoplasia in a tumor-suppressor milieu. It is likely that transcriptomics and network analyses, especially if interfaced with proteomic analysis, can help in further defining the neuroendocrine cellular toolkit. This strategy will contribute to resolving the oncologic conundrum of GEP-NEN as well as facilitating accurate molecular delineation of NEN disease.

With this approach in mind, a complete description of the master regulators and nexus genes is required to define what regulates metastasis and to identify candidate drug targets based firmly on the pathobiologic rationale of neuroendocrine neoplasia. Of particular relevance is the need to define the regulator changes that occur as the primary tumor evolves into a metastatic phenotype and in so doing undergoes alteration in its spectrum of master regulators and druggable targets. A further important issue is to define accurate reporter systems that can predict and measure the efficacy of drug therapies. Because repetitive biopsy of metastases is not a viable clinical option, the development of blood-based strategies to measure and assess changes in the circulating molecular signature are of critical relevance to both management strategy and outcome analysis. The acquisition of answers to these critical questions will be of clinical utility for the development of novel imaging, multianalyte algorithmic analyte biomarkers, and the advance of NEN-specific therapeutic strategies.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest The authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding This work has been supported by Clifton Life Sciences.

References

- 1.Modlin I.M., Oberg K., Chung D.C. Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:61–72. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70410-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strosberg J. Evolving treatment strategies for management of carcinoid tumors. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2013;14:374–388. doi: 10.1007/s11864-013-0246-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baudin E., Planchard D., Scoazec J.Y. Intervention in gastro-enteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;26:855–865. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2013.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Modlin I.M., Kidd M., Latich I. Current status of gastrointestinal carcinoids. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1717–1751. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yao J.C., Hassan M., Phan A. One hundred years after “carcinoid”: epidemiology of and prognostic factors for neuroendocrine tumors in 35,825 cases in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3063–3072. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.4377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ellis L., Shale M.J., Coleman M.P. Carcinoid tumors of the gastrointestinal tract: trends in incidence in England since 1971. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2563–2569. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maggard M.A., O’Connell J.B., Ko C.Y. Updated population-based review of carcinoid tumors. Ann Surg. 2004;240:117–122. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000129342.67174.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lawrence B., Gustafsson B.I., Chan A. The epidemiology of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2011;40:1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2010.12.005. vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Modlin I.M., Moss S.F., Chung D.C. Priorities for improving the management of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1282–1289. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Powell A.C., Libutti S.K. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1: clinical manifestations and management. Cancer Treat Res. 2010;153:287–302. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-0857-5_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Mestier L., Dromain C., d’Assignies G. Evaluating digestive neuroendocrine tumor progression and therapeutic responses in the era of targeted therapies: state of the art. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2014;21:R105–R120. doi: 10.1530/ERC-13-0365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bergsland E.K. The evolving landscape of neuroendocrine tumors. Semin Oncol. 2013;40:4–22. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2012.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]