Abstract

In vitiligo, melanocytes are particularly vulnerable to oxidative stress owing to the pro-oxidant state generated during melanin synthesis and to the genetic antioxidant defects. Autophagy is a controlled self-digestion process which can protect cells against oxidative damage. However, the exact role of autophagy in vitiligo melanocytes in response to oxidative stress and the mechanism involved are still not clear. To determine the implications of autophagy for melanocyte survival in response to oxidative stress, we first detected the autophagic flux in normal melanocytes exposure to H2O2, and found that autophagy was significantly enhanced in normal melanocytes, for protecting cells against H2O2-induced oxidative damage. Nevertheless, vitiligo melanocytes exhibited dysregulated autophagy and hypersensitivity to H2O2-induced oxidative injury. In addition, we confirmed that the impairment of Nrf2-p62 pathway is responsible for the defects of autophagy in vitiligo melanocytes. Noteworthily, upregulation of the Nrf2-p62 pathway or p62 reduced H2O2-induced oxidative damage of vitiligo melanocytes. Therefore, our data demonstrated that dysregulated autophagy owing to the impairment of Nrf2-p62 pathway increase the sensitivity of vitiligo melanocytes to oxidative stress, thus promote the development of vitiligo. Upregulation of p62-dependent autophagy may be applied to vitiligo treatment in the future.

Vitiligo is defined as a common depigmentary disease characterized by the destruction of melanocytes in the epidermis1. In both lesional and non-lesional skin of vitiligo patients, increased levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) were observed, accompanied with reduced levels and activity of catalase2,3,4,5,6. It is well known that normal melanocytes are vulnerable to excessive ROS for their specialized function of melanin synthesis, which would result in a highly pro-oxidant state in the epidermis7,8. In fact, vitiligo melanocytes are particularly more sensitive to the accumulated ROS owing to the intrinsic antioxidant defects8–10. This imbalance between the pro-oxidants and the antioxidant status can disrupt the homeostasis of melanocytes, causing accumulation of oxidized and damaged proteins or organelles, and consequently lead to the destruction of melanocytes7,11.

Autophagy is a regulated cellular self-digestion process in which damaged intracellular proteins or organelles are sequestered and then transported to degrade in lysosomes for maintenance of cell homeostasis12. Interestingly, it has been discovered that constitutive autophagic activity is especially required to prevent oxidative damage and achieve the full proliferative capacity of normal melanocytes13. However, the exact role of autophagy in vitiligo melanocytes in response to oxidative stress has not been elucidated to date.

Nuclear factor E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) is a critical transcription factor in protecting melanocytes from oxidative damage14. It is well established that Nrf2 exerts its protective effect by binding to the antioxidant response element (ARE) sequence and therefore promotes the expression of antioxidant genes15,16. Noteworthily, recent studies suggest that Nrf2-ARE pathway protects cells from various pro-oxidant stimuli via the induction of autophagy17,18. Thus, we speculated that Nrf2 serve as an essential upstream regulator of autophagy in stressed melanocytes. Our previous study has found vitiligo melanocytes showing functional defect in Nrf2-ARE pathway under the oxidative stress10. Hence, we further hypothesized that impaired autophagy caused by the dysregulation of Nrf2 pathway may increase the sensitivity of vitiligo melanocytes to oxidative stress and contribute to the pathogenesis of vitiligo.

To test our hypothesis, we first detected the autophagy flux in normal and vitiligo melanocytes exposure to H2O2. Then, we confirmed the protective effects of autophagy on melanocytes against H2O2-induced oxidative stress. Furthermore, we elucidated whether H2O2-induced Nrf2 activation contributes to autophagic activity. The underlying mechanisms were investigated as well.

Results

H2O2-induced oxidative stress increased autophagy flux in melanocytes

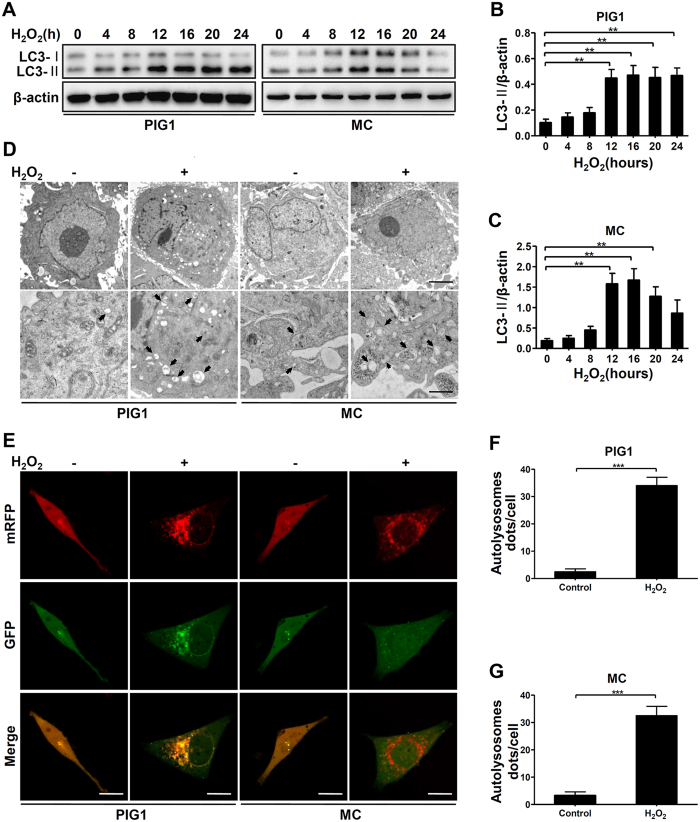

We firstly examined the autophagy levels of primary normal human melanocyte (MC) and the human melanocyte cell line (PIG1) treated with H2O2. We found the microtubule associated protein 1 light-chain 3 (LC3)-II, the most widely used biomarker of autophagosome formation, was significantly increased in MC and PIG1 cells following H2O2 treatment (Fig. 1A–C). And the conversion of LC3-I to LC3-II reached the highest level after 12 hours of H2O2 exposure in both groups (Fig. 1A–C). Subsequent ultrastructural transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis also showed that after exposure to H2O2 for 12 hours, MC and PIG1 cells displayed many cytoplasmic vesicles that had the typical single-membrane structure of autolysosome, whereas few autophagic vacuoles were observed in control cells (Fig. 1D). To further confirm the enhancement of autophagic flux induced by oxidative stress, mRFP-GFP-LC3 tandem construc was introduced. The results showed after exposure to H2O2 for 12 hours, both autophagosome (yellow puncta) and autolysosomes (red puncta) were increased in MC and PIG1 cells, whereas no significant changes were observed in control cells (Fig. 1E–G). These data demonstrated that H2O2-induced oxidative stress can induce autophagy in normal melanocytes.

Figure 1. H2O2 treatment increases autophagy flux in melanocytes.

(A) Immunoblots of LC3 in MC and PIG1 cells treated with H2O2 (0.5 mM) for different hours. (B,C) Band intensity normalized to β-actin is expressed as mean ± SD, **p < 0.01. (D) TEM images of autophagic vacuoles in cells treated with or without H2O2 for 12 hours. Arrows indicate the autolysosome. Scale bars represent 1 μm (upper row) and 500 nm (lower row). (E) MC and PIG1 cells were transfected with adenovirus expressing mRFP-GFP-LC3. After a 24-hour transfection, cells were treated with or without H2O2 for 12 hours. As shown in merged confocal images, the yellow puncta indicate the autophagosome while the red puncta indicate the autolysosome. Scale bars represent 5 μm. (F,G) The number of autolysosome dots were counted on 40 cells in a minimum of 3 experiments and expressed as mean ± SD, ***p < 0.001.

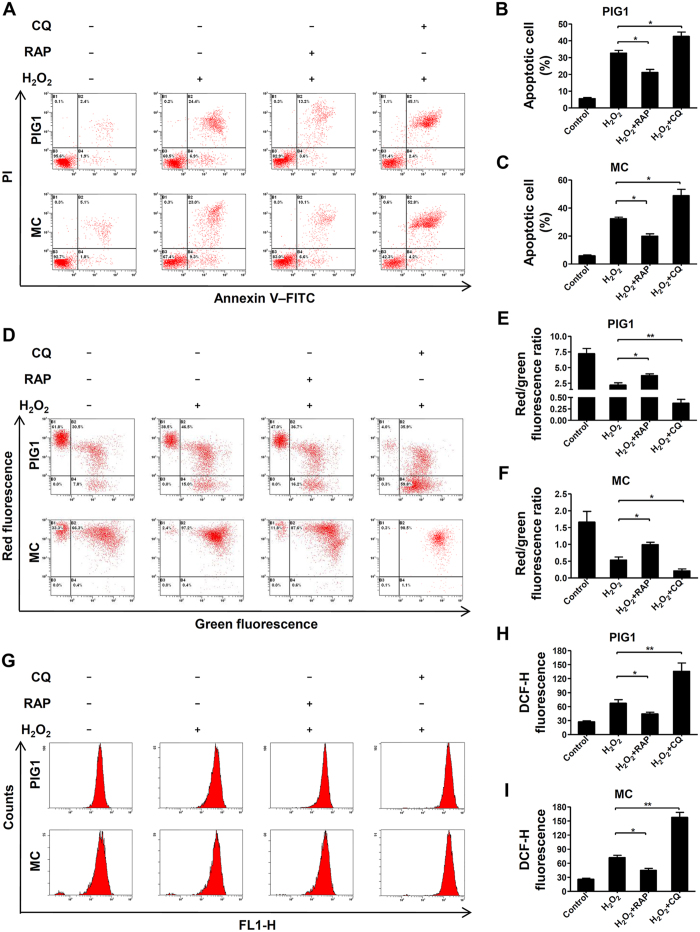

Autophagy protected melanocytes from oxidative stress-induced cell apoptosis, loss of mitochondrial membrane potential and ROS generation

We next identified the role of autophagy under oxidative stress in normal melanocytes. Cells were pretreated by rapamycin (RAP) to increase autophagic flux19, or chloroquine (CQ) to block autophagic activity20 in MC and PIG1 prior to treatment with H2O2. The results showed that addition of RAP significantly reduced cell apoptosis induced by H2O2, whereas CQ further promoted H2O2–induced apoptosis in both MC and PIG1 cells (Fig. 2A–C). Moreover, by using JC-1 dye and measuring the red/green ratio, a significant decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) was detected in both MC and PIG1 cells following exposure to H2O2 for 24 hours, which were further promoted by CQ pretreatment, while the RAP rescued the cells from the loss of MMP (Fig. 2D). In addition, we investigated whether autophagy could eliminate excessive ROS induced by H2O2. As shown in Fig. 2E–G, the level of intracellular ROS induced by H2O2 was significantly attenuated when cells were pretreated with RAP, whereas CQ obviously increased H2O2-induced ROS generation. Taken together, these results confirmed that autophagy play a critical role in protecting normal melanocytes from oxidative stress-induced cell apoptosis, loss of MMP and intracellular ROS generation.

Figure 2. Increased autophagy protects melanocytes against oxidative stress while reduced autophagy renders cells more susceptible to oxidative stress.

(A) MC and PIG1 cells were pretreated with rapamycin (RAP, 400 nM) or chloroquine (CQ, 50 μM) for 2 hours and treated with H2O2 (0.5 mM) for 24 hours, then the level of apoptosis was detected by flow cytometry assay. (B,C) The level of apoptosis are presented as the mean ± SD, *p < 0.05. (D) MC and PIG1 cells were pretreated with rapamycin or chloroquine for 2 hours and treated with H2O2 for 24 hours, then the MMP was measured by flow cytometry assay. (E,F) Quantification of MMP are presented as the mean ± SD, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. (G) MC and PIG1 cells were pretreated with rapamycin or chloroquine for 2 hours and treated with H2O2 for 24 hours, then the intracellular ROS level was quantized by flow cytometry assay. (H,I) Quantification of intracellular ROS level are presented as the mean ± SD, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

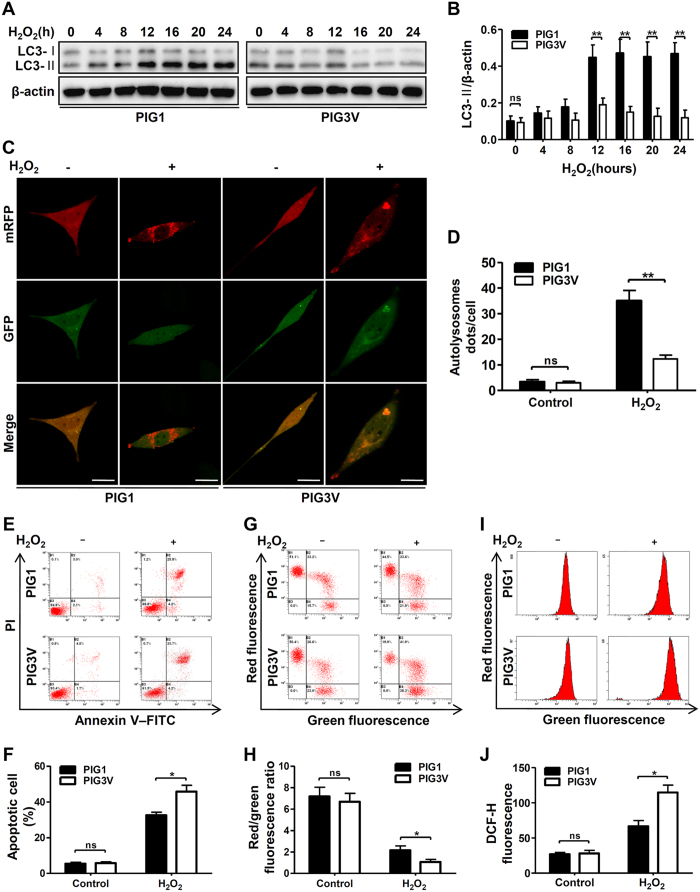

Vitiligo melanocytes displayed impaired autophagy and increased sensitivity to H2O2-induced oxidative stress

To evaluate whether autophagy was involved in the higher susceptibility to oxidative stress in vitiligo melanocytes, we first measured the level of autophagy in a vitiligo melanocyte cell line (PIG3V) exposed to H2O2. The results showed that after treatment with H2O2 for 12 hours, both the level of LC3-II and the ratio of LC3-II/-I were relatively lower in the PIG3V cells compared to that in PIG1 cells (Fig. 3A–C). According to mRFP-GFP-LC3 puncta formation assays, fewer autolysosomes dots in PIG3V cells were observed following H2O2 treatment for 12 hours than those of PIG1 cells (Fig. 3D). These observations suggested that vitiligo melanocytes have faint autophagic induction in response to H2O2-induced oxidative stress.

Figure 3. The difference in autophagy flux and cells sensitivity after H2O2 treatment between PIG1 and PIG3V cells.

(A) Immunoblots of LC3 in PIG1 and PIG3V cells treated with H2O2 (0.5 mM) for different hours. (B) Band intensity normalized to β-actin is expressed as mean ± SD, **p < 0.01. (C) PIG1 and PIG3V cells were transfected with adenovirus expressing mRFP-GFP-LC3. After a 24-hour transfection, cells were treated with or without H2O2 for 12 hours. As shown in merged confocal images, the yellow puncta indicate the autophagosome while the red puncta indicate the autolysosome. Scale bars represent 5 μm. (D) The number of autolysosome dots were counted on 40 cells in a minimum of 3 experiments and expressed as mean ± SD, **p < 0.01. (E) PIG1 and PIG3V cells were treated with H2O2 for 24 hours, and the level of apoptosis was detected by flow cytometry assay. (F) The level of apoptosis are presented as the mean ± SD, *p < 0.05. (G) PIG1 and PIG3V cells were treated with H2O2 for 24 hours, and the MMP was measured by flow cytometry assay. (H) Quantification of MMP are presented as the mean ± SD, *p < 0.05. (I) PIG1 and PIG3V cells were treated with H2O2 for 24 hours, then the intracellular ROS level were measured by flow cytometry assay. (J) Quantification of intracellular ROS level are presented as the mean ± SD, *p < 0.05.

We further evaluated the effect of decreased autophagy in vitiligo melanocytes under oxidative stress by determine cell apoptosis, MMP and ROS generation. Compared to PIG1 cells, treatment of H2O2 caused more increased apoptosis (Fig. 3E,F), more reduced MMP (Fig. 3G,H), and more accumulated intracellular ROS (Fig. 3I,J) in PIG3V cells. Taken together, we concluded that vitiligo melanocytes with decreased autophagyic activity were more sensitive to H2O2-induced oxidative stress.

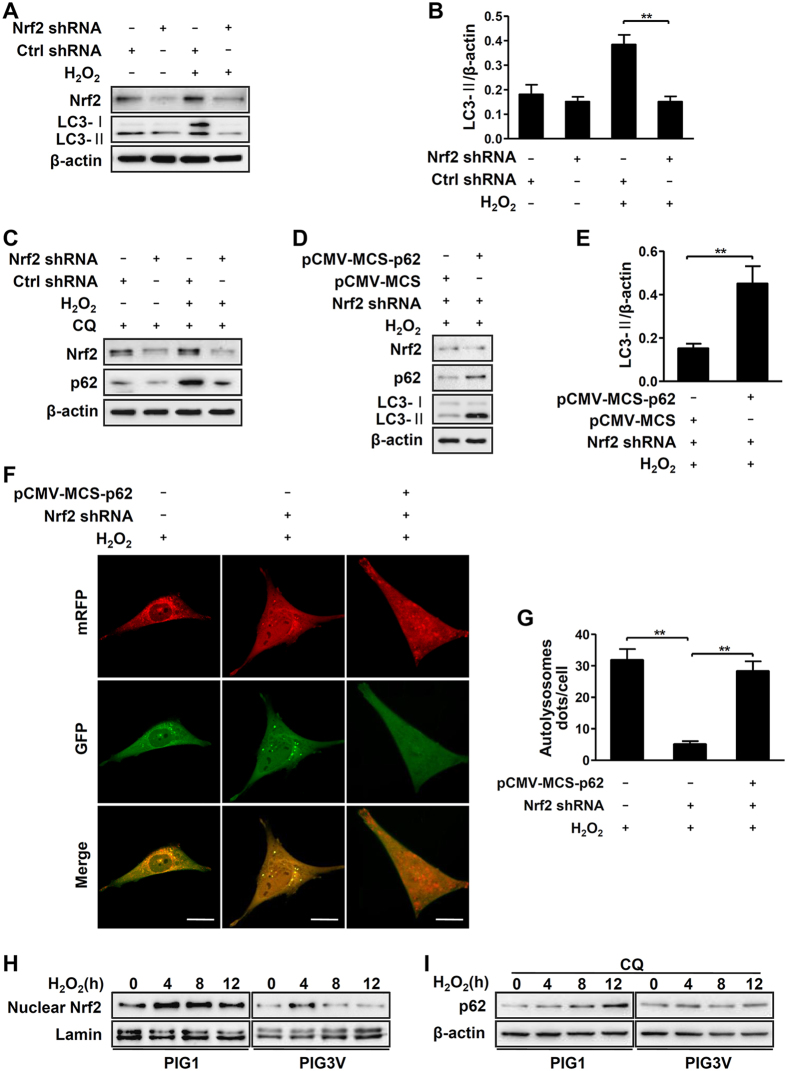

Aberrant Nrf2-p62 signaling pathway is responsible for impaired autophagy in vitiligo melanocytes under oxidative stress

Our previous study had ascertained that Nrf2 pathway has crucial role in protecting melanocytes from oxidative damage14. Meanwhile, recent studies have suggested that Nrf2 pathway protects cells from various pro-oxidant stimuli also via the induction of autophagy18. Therefore, we investigated whether Nrf2 pathway contributes to increase autophagy in normal melanocytes. Our results showed that the knockdown of Nrf2 by shRNA significantly attenuated the levels of LC3-II induced by H2O2 (Fig. 4A,B). Considering that Nrf2 contributes to the induction of p62/sequestosome1 which functions as an autophagic adaptor21, we examined whether the expression of p62 would be affected in normal melanocytes under H2O2-induced oxidative stress. Since p62 could also be degraded by autophagy, we detected the basic protein levels of p62 by addition of chloroquine which can block autophagic flux. As shown in Fig. 4C, Nrf2 knockdown blocked the expression of p62 in normal melanocytes. Furthermore, we restored the protein level of p62 in Nrf2 knockdown cells under oxidative stress, and observed that the declined LC3-II protein levels were rescued (Fig. 4D,E). Consistently, mRFP-GFP-LC3 puncta formation assays detected attenuated autolysosome puncta in Nrf2-knockdowned cells, whereas the number of the puncta significantly increased in these cells after over-expression of p62 (Fig. 4F,G). These data indicated that H2O2-induced autophagy can be regulated by the Nrf2-p62 pathway in normal melanocytes.

Figure 4. Nrf2-p62 pathway affected autophagy in melanocytes.

. (A) Immunoblots of Nrf2 and LC3 in PIG1 cells expressing Nrf2 shRNA, in the absence or presence of H2O2 (0.5 mM) for 12 hours. (B) The ratio of LC3-II/β-actin is presented as mean ± SD, **p < 0.01. (C) With chloroquine (CQ, 50 μM) pre-treatment, PIG1 cells expressing Nrf2 shRNA were treated with or without H2O2 for 12 hours. The expression level of Nrf2 and p62 were detected by western blotting. (D) PIG1 cells expressing Nrf2 shRNA were transfected with or without pCMV-MCS-p62 for 36 hours and then treated with H2O2 for 12 hours. The expression level of Nrf2, p62 and LC3 were detected by western blotting. (E) The ratio of LC3-II/β-actin is presented as mean ± SD, **p < 0.01. (F) PIG1 cells expressing Nrf2 shRNA were transfected with adenovirus expressing mRFP-GFP-LC3. After a 12-hour transfection, cells were treated with or without pCMV-MCS-p62 for 36 hours and then treated with H2O2 for 12 hours. As shown in merged confocal images, the yellow puncta indicate the autophagosome while the red puncta indicate the autolysosome. Scale bars represent 5 μm. (G) The number of autolysosome dots were counted on 40 cells in a minimum of 3 experiments and expressed as mean ± SD, **p < 0.01. (H) Immunoblots of nuclear Nrf2 in PIG1 and PIG3V cells treated with H2O2 for different hours. (I) Immunoblots of p62 in PIG1 and PIG3V cells co-treated with chloroquine and H2O2 for different hours.

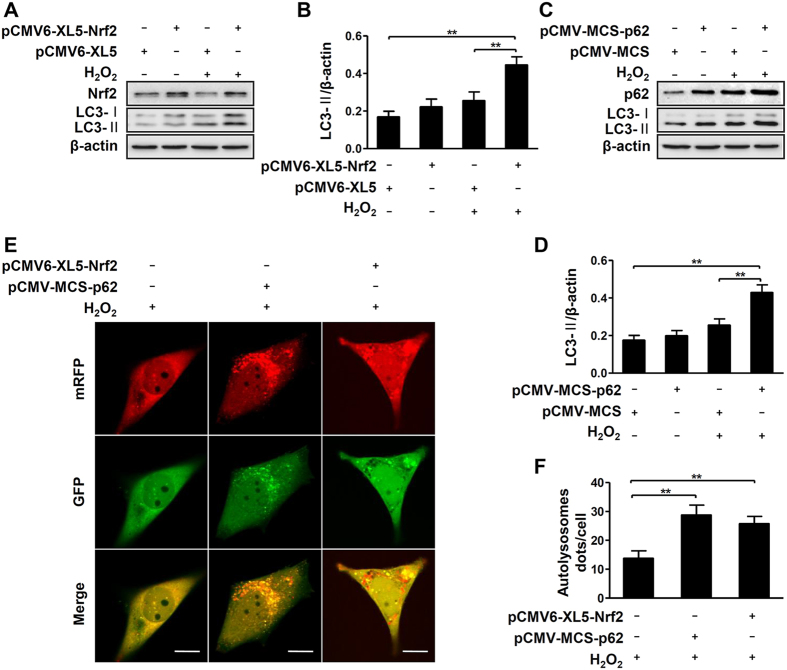

We found both the nuclear Nrf2 translocation and basic protein levels of p62 failed to increase in response to H2O2-treated PIG3V cells compared to normal melanocytes (Fig. 4H,I). indicating an aberrant Nrf2-p62 signaling pathway in vitiligo melanocytes. Therefore, we further investigated whether the aberrant Nrf2-p62 pathway was the culprits for the damaged autophagy in vitiligo melanocytes under oxidative stress. Interestingly, upregulation of Nrf2 expression increased the protein levels of LC3-II in PIG3V cells after exposure to H2O2 (Fig. 5A,B). The increased LC3-II was correspondingly detected in p62-overexpressed PIG3V cells during oxidative stress (Fig. 5C,D). Moreover, increased autolysosome puncta were detected in both Nrf2- and p62-overexpressed PIG3V cells in response to H2O2 (Fig. 5E,F). Taken together, these results proved that aberrant Nrf2-p62 signaling pathway is responsible for impaired autophagy in vitiligo melanocytes under oxidative stress.

Figure 5. Upregulation of Nrf2 or p62 promotes H2O2-induced autophagy in vitiligo melanocytes.

(A) Immunoblots of Nrf2 and LC3 in PIG3V cells which were transfected with pCMV6-XL5-Nrf2 for 36 hours and then were treated with H2O2 (0.5 mM) for 12 hours. (B) The ratio of LC3-II/β-actin is presented as mean ± SD, **p < 0.01. (C) Immunoblots of p62 and LC3 in PIG3V cells which were transfected with pCMV-MCS-p62 for 36 hours and then treated with H2O2 for 12 hours. (D) The ratio of LC3-II/β-actin is presented as mean ± SD, **p < 0.01. (E) PIG3V cells were transfected with adenovirus expressing mRFP-GFP-LC3. After a 12-hour transfection, cells were transfected with pCMV6-XL5-Nrf2 or pCMV-MCS-p62 for 36 hours and then treated with H2O2 for 12 hours. As shown in merged confocal images, the yellow puncta indicate the autophagosome while the red puncta indicate the autolysosome. Scale bars represent 5 μm. (F) The number of autolysosome dots were counted on 40 cells in a minimum of 3 experiments and expressed as mean ± SD, **p < 0.01.

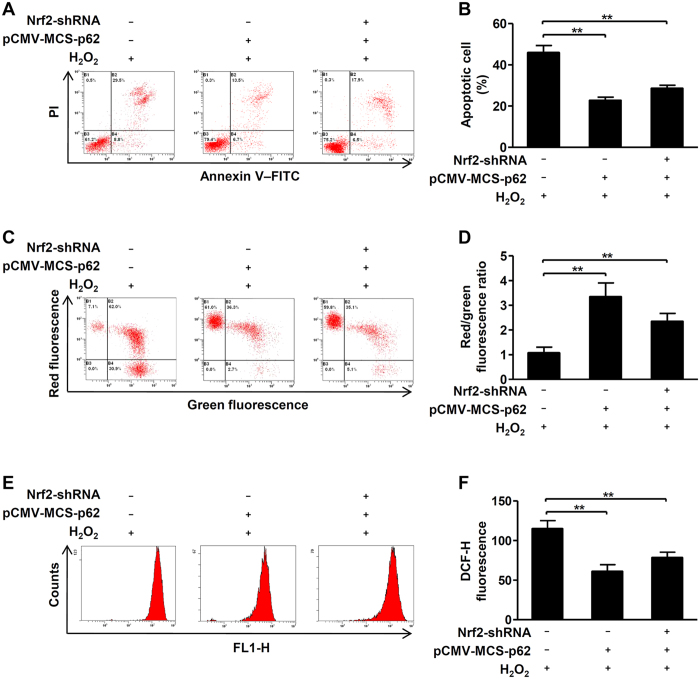

Upregulation of p62 reduces cytotoxicity of vitiligo melanocytes under H2O2-induced oxidative stress

Finally, we try to investigate whether upregulation of p62 expression could reduce the cytotoxicity only by promoting autophagy in vitiligo melanocytes under oxidative stress. Of note, our results showed that upregulation of p62 significantly reduced cell apoptosis (Fig. 6A,B), restored the loss of MMP (Fig. 6C,D), and eliminated excessive intracellular ROS (Fig. 6E,F) in PIG3V cells and in Nrf2-knockdown cells treated with H2O2. All the above data demonstrated that even upregulation of p62 can independently protect vitiligo melanocytes against H2O2-induced oxidative stress.

Figure 6. Upregulation of p62 reduces sensitivity of vitiligo melanocytes to H2O2-induced oxidative stress.

(A) PIG3V cells were stably infected with or without the Nrf2 shRNA, then cells were transfected with or without pCMV-MCS-p62 for 24 hours and then treated with H2O2 (0.5 mM) for 24 hours, the level of apoptosis was detected by flow cytometry assay. (B) The level of apoptosis are presented as the mean ± SD, **p < 0.01. (C) PIG3V cells were stably infected with or without the Nrf2 shRNA, then cells were transfected with pCMV-MCS-p62 for 24 hours and then treated with H2O2 for 24 hours, the MMP was measured by flow cytometry assay. (D) Quantification of MMP are presented as the mean ± SD, **p < 0.01. (E) PIG3V cells were stably infected with or without the Nrf2 shRNA, then cells were transfected with pCMV-MCS-p62 for 24 hours and then treated with H2O2 for 24 hours, the intracellular ROS level was quantized by flow cytometry assay. (F) Quantification of intracellular ROS level are presented as the mean ± SD, **p < 0.01.

Discussion

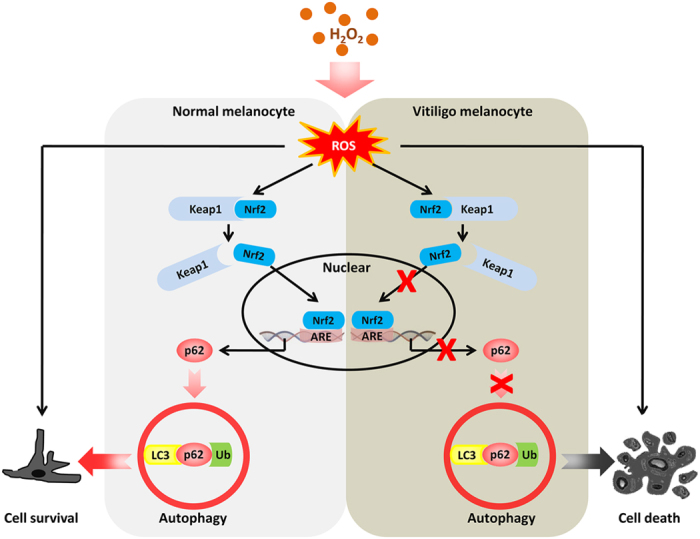

In this study, we firstly found that H2O2-induced oxidative stress enhances autophagic flux in primary human melanocytes against oxidative damage, and then established that Nrf2-p62 is an essential pathway in protecting melanocytes against H2O2-induced oxidative damage. Moreover, we confirmed that vitiligo melanocytes under H2O2-induced oxidative stress showed lower autophagic flux owing to the dysfunction of Nrf2-p62 pathway, which resulted in increased susceptibility to excessive ROS (Fig. 7). Giving the first evidence, our data pointed that the enhancement of autophagic activity is sufficient to reduce the oxidative damage in vitiligo melanocytes. Modification of autophagy may provide a promising therapy for vitiligo.

Figure 7. Nrf2-p62 pathway regulates autophagy in normal human melanocytes and vitiligo melanocytes under H2O2-induced oxidative stress.

Under H2O2-induced oxidative stress in normal human melanocytes, Nrf2 dissociates from Kelch-like ECH-associated protein (Keap1) and then translocates to the nucleus where it binds to ARE and finally upregulates p62 expression. Upregulation of p62 can further promote cell autophagy and then protect melanocytes from H2O2-induced oxidative damage. On the contrary, in vitiligo melanocytes, impaired activation of the Nrf2-p62 pathway leads to decreased p62 expression, which fails to induce cell autophagy and then cause cell death exposed to H2O2-induced oxidative stress.

Autophagy is a key catabolic process that helps to maintain cell homeostasis under oxidative stress19,22,23. Because of the process of melanogenesis, excessive ROS is accumulated in melanocytes. Recently, Zhang et al. has reported their research on the autophagy process in melanocytes by detecting LC3, a classical protein marker for autophagy. Their study demonstrates that autophagy functions as a self-defense mechanism in mouse melanocytes against oxidative stress13. Since LC3 could be found in melanosomes, our study also used ultrastructural TEM to observe direct changes of autophagy flux in melanocytes, trying to exclude the interference of melanosomes when detecting autophagy using LC3 only. Noteworthily, the results of our TEM assay were always consistent with the ratio of LC3II/I detected by western blot in our study, indicating that using LC3 to detect autophagy in melanocytes is still feasible in spite of little expression of LC3 in melanosomes. Our results provide the first evidence that autophagy occurs to alleviate the oxidative damage as a part of cellular repair process in normal human melanocytes. Therefore, in addition to classical antioxidant system such as antioxidant genes or enzymes7, autophagy can protect melanocytes from oxidative stress, and consequently contribute to the cell homeostasis.

Our previous study has demonstrated that vitiligo melanocytes equipped with impaired antioxidant system, including the genetic defects of antioxidant enzymes9, dysfunctional Nrf2-HO1 antioxidant signaling pathway10, as well as aberrant expression of miRNAs24. In the current study, we confirmed that defects in autophagy could increase the apoptotic death and raise the intracellular ROS levels, as well as reducing the MMP in vitiligo melanocytes. These observations provide new evidences to explain why vitiligo melanocytes are more vulnerable to H2O2-induced oxidative damage compared to normal melanocytes.

Recently, several lines of evidence support an essential role for Nrf2 in the induction of autophagy, but the underlying mechanisms are still not fully understood17,18. It is well known that during autophagy, intracellular proteins and organelles can be banded to autophagosome by the adaptor protein p6225, which can be induced by the activation of Nrf2 under oxidative stress21. Moreover, Nrf2-mediated induction of p62 has been implicated in controlling Toll-like receptor-4 (TLR4)–driven selective autophagy structure formation and autophagic degradation26, as well as in cigarette smoke-induced autophagy in airway epithelial cells17. In this study, we also identified that Nrf2-mediated p62 upregulation is required for oxidative stress-induced autophagy in normal human melanocytes.

However, unlike normal melanocytes, both the activation of Nrf2 and the basic protein levels of p62 failed to increase in response to oxidative stress in vitiligo melanocytes. Notably, upregulation of Nrf2-p62 pathway increased the autophagic activity in vitiligo melanocytes, and therefore contributed to cell survival. These data suggested that the impairment of Nrf2-p62 pathway is responsible for the defects of autophagy in vitiligo melanocytes. Although several studies have reported that p62 could protect cells from oxidative damage via activation of Nrf227,28, our current study demonstrated that even without activation of Nrf2, upregulation of autophagic flux by increasing p62 is sufficient to protect vitiligo melanocytes from H2O2-induced oxidative damage. These findings strengthen the importance of p62-dependent autophagy in melanocytes survival, providing a potential strategy for vitiligo treatment.

It has to be pointed out that only one vitiligo melanocyte cell line (PIG3V) was used in the current study. Considering that the genetic backgrounds vary among vitiligo patients, the cell line that we used can not completely represent the features of vitiligo melanocytes. Our findings need to be validated in other melanocyte lines extracted from vitiligo patients in future studies.

In conclusion, our study uncovers an essential role for autophagy in protecting normal human melanocytes from oxidative stress. Importantly, the dysregulation of Nrf2-p62 pathway causes the defects of autophagy under the condition of oxidative stress, which contributes to enhanced sensitivity of vitiligo melanocytes to oxidative stress. Our findings indicate a prospective treatment of upregulating p62-dependent autophagy for vitiligo.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and reagents

Primary normal human melanocytes were isolated from human foreskin specimens obtained during circumcision surgery. The primary melanocytes were grown in Medium 254 (Cascade Biologics, Portland, OR, USA) containing Human Melanocyte Growth Supplement (Cascade Biologics). The primary melanocytes were used between 2nd and 4th passage in all experiments. The immortalized normal human epidermal melanocyte cell line PIG1 and a vitiligo melanocyte cell line PIG3V (both gifts from Dr. Caroline Le Poole, Loyola University Chicago, Maywood, IL, USA) was cultured in Medium 254 (Cascade Biologics) containing Human Melanocyte Growth Supplement (Cascade Biologics) and 5% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA, USA). Cells were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. H2O2 (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) was used at concentration of 500 μM. Rapamycin (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) was used at concentration of 400 nM. Chloroquine (Sigma-Aldrich) was used at concentration of 50 μM. All subjects consented by written and informed agreement for inclusion in this study. All experiment protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Fourth Military Medical University, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki principles.

Lentiviral infection

Cells were infected with Nrf2 shRNA (5′-GGGAGGAGCTATTATCCATTC-3′, Genepharma, Shanghai, China) or Ctrl shRNA (Genepharma, Shanghai, China) at a 1:4 dilution in the presence of 5 μg/mL polybrene (Genepharma, Shanghai, China). After 24 h, cells harboring the Nrf2 shRNA or Ctrl shRNA cassettes were selected in the presence of puromycin (0.3 μg/ml; abcam) for 3 days. Expression of the constructs was confirmed by western blotting.

Plasmids and transfection

Cells were seeded at 2 × 105 cells per well for 24 hours before transfection. Cells were transfected with pCMV6-XL5-Nrf2 (OriGene, MD, USA) or pCMV-MCS-p62 (Genechem, Shanghai, China) at 4 mg per well for 6-well plates by Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen). After 48-hour incubation, cells were assessed protein changes. The pCMV6-XL5 or pCMV-MCS transfection and control cells (no transfection) were included in each experiment.

Western blot

Cells were washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and lysed in RIPA buffer (Runde Biologicals, Xi’an, China) containing phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (protease inhibitor mix; Sigma-Aldrich). Equal amounts of the protein samples were separated on a 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel and blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). After blocking by 5% non-fat dry milk, the membranes were washed and incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. After washing, the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature. Bound antibodies were detected using a chemiluminescence detection kit (KPL, Gaithersburg, MD). Primary antibodies against LC3 I/II and p62 were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Danvers, MA; Antibodies against Nrf2 were purchased from Abcam, MA; Anti-Lamin and anti-β-actin were purchased from Life Science Products &Services, shanghai, China. Second antibodies including anti-mouse IgG or anti-rabbit IgG were purchased from Santa Cruz. Band intensities were determined by software (ImageJ; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

Detection of apoptosis

After experimental treatment, cells were detected by the Annexin V/PI Apoptosis Detection Kit (MaiBio, Shanghai, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions and identified in flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Miami, USA) within an hour. The analysis was done with Expo32 software (Beckman Coulter).

Assay for ROS levels

After experimental treatments, cells were washed with PBS and incubated in PBS containing 10 mM CM-H2DCFDA (Invitrogen) for 30 min at 37 °C in the dark. Then cells were washed twice in PBS, and fluorescence was measured by flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter) within an hour. Mean fluorescence intensity was quantized with Expo32 software (Beckman Coulter).

Measurement of mitochondrial membrane potential

After experimental treatments, cells were washed with PBS and loaded with JC-1 dye (Invitrogen) 5 mg/mL for 20 min at 37 °C. Then cells were washed twice in PBS, and fluorescence was measured by flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter) within an hour. Mean fluorescence intensity was quantized with Expo32 software (Beckman Coulter) and red/green ratio was calculated as an indicator of mitochondrial membrane potential.

Transmission electron microscopy

After experimental treatments, cells were collected and washed in cold PBS, fixed in fixative buffer for 24 hours at 4 °C. Then the cell pellet was rinsed with Millonig’s buffer and minced post-fixed in 1.0% OsO4, The pellet was stained with 2.0% aqueous uranyl acetate followed by ethanol dehydration, and embedded in Spurr’s plasticresin. Ultrathin section analysis was visualized using a Tecnai™ G2 Spirit Bio Twin (FEI, Hillsboro, OR).

Tandem mRFP-GFP-LC3 fluorescence microscopy

Cells were transfected with adenovirus expressing mRFP-GFP-LC3 (Hanbio, Shanghai, China) at 10 MOI for 24 h, and then treated with or without other agentia. The cells were analyzed by confocal laser scanning microscopy (LSM510; Carl Zeiss AB, Jena, Germany).

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was performed at least for three times, and statistical analyses of the data were performed using unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-tests or using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Newman-Keuls test built into GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software 5.0; San Diego, CA). All the data were expressed as mean ± SD. Differences with P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: He, Y. et al. Dysregulated autophagy increased melanocyte sensitivity to H2O2-induced oxidative stress in vitiligo. Sci. Rep. 7, 42394; doi: 10.1038/srep42394 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Caroline Le Poole for providing the immortalized human epidermal melanocyte cell line PIG1 and vitiligo melanocyte cell line PIG3V. This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos 81625020, 81472863 and 81130032).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions Y.H., S.L., and C.L. designed the experiments. Y.H., S.L., W.Z., W.D., and T.C. carried out the experiments. Y.H., S.L., G.W., T.G., and C.L. analyzed the results. Y.H., S.L., W.Z., and W.D. wrote the main manuscript text. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

References

- Ongenae K. et al. Psychosocial effects of vitiligo. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 20, 1–8 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boissy R. E. & Manga P. On the etiology of contact/occupational vitiligo. Pigment Cell Res 17, 208–214 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schallreuter K. U. et al. Low catalase levels in the epidermis of patients with vitiligo. J Invest Dermatol 97, 1081–1085 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schallreuter K. U. et al. Blunted epidermal L-tryptophan metabolism in vitiligo affects immune response and ROS scavenging by Fenton chemistry, part 1: Epidermal H2O2/ONOO(−)-mediated stress abrogates tryptophan hydroxylase and dopa decarboxylase activities, leading to low serotonin and melatonin levels. FASEB J 26, 2457–2470 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sravani P. V. et al. Determination of oxidative stress in vitiligo by measuring superoxide dismutase and catalase levels in vitiliginous and non-vitiliginous skin. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 75, 268–271 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z. et al. Decreased methionine sulphoxide reductase A expression renders melanocytes more sensitive to oxidative stress: a possible cause for melanocyte loss in vitiligo. Br J Dermatol 161, 504–509 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denat L. et al. Melanocytes as instigators and victims of oxidative stress. J Invest Dermatol 134, 1512–1518 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laddha N. C. et al. Vitiligo: interplay between oxidative stress and immune system. Exp Dermatol 22, 245–250 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. et al. AHR promoter variant modulates its transcription and downstream effectors by allele-specific AHR-SP1 interaction functioning as a genetic marker for vitiligo. Sci Rep 5, 13542 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jian Z. et al. Impaired activation of the Nrf2-ARE signaling pathway undermines H2O2-induced oxidative stress response: a possible mechanism for melanocyte degeneration in vitiligo. J Invest Dermatol 134, 2221–2230 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckman J. S. & Koppenol W. H. Nitric oxide, superoxide, and peroxynitrite: the good, the bad, and ugly. Am J Physiol 271, C1424–1437 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima N. et al. Autophagy fights disease through cellular self-digestion. Nature 451, 1069–1075 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C. F. et al. Suppression of autophagy dysregulates the antioxidant response and causes premature senescence of melanocytes. J Invest Dermatol 135, 1348–1357 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jian Z. et al. Heme oxygenase-1 protects human melanocytes from H2O2-induced oxidative stress via the Nrf2-ARE pathway. J Invest Dermatol 131, 1420–1427 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaspar J. W. et al. Nrf2:INrf2 (Keap1) signaling in oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med 47, 1304–1309 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niture S. K. et al. Nrf2 signaling and cell survival. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 244, 37–42 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L. et al. Regulation of Cigarette Smoke (CS)-Induced Autophagy by Nrf2. PLoS One 8, e55695 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Zhang L. et al. The Relevance of Nrf2 Pathway and Autophagy in Pancreatic Cancer Cells upon Stimulation of Reactive Oxygen Species. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2016, 3897250 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitter S. K. et al. Dysregulated autophagy in the RPE is associated with increased susceptibility to oxidative stress and AMD. Autophagy 10, 1989–2005 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klionsky D. J. et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy. Autophagy 8, 445–544 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain A. et al. p62/SQSTM1 is a target gene for transcription factor NRF2 and creates a positive feedback loop by inducing antioxidant response element-driven gene transcription. J Biol Chem 285, 22576–22591 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou X. et al. SIRT1 positively regulates autophagy and mitochondria function in embryonic stem cells under oxidative stress. Stem Cells 32, 1183–1194 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman M. et al. Reactive oxygen species regulation of autophagy in skeletal muscles. Antioxid Redox Signal 20, 443–459 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Q. et al. Oxidative stress-induced overexpression of miR-25: the mechanism underlying the degeneration of melanocytes in vitiligo. Cell Death Differ 23, 496–508 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurzer B. et al. Oligomerization of p62 allows for selection of ubiquitinated cargo and isolation membrane during selective autophagy. Elife 4, e08941 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita K. et al. Nrf2-mediated induction of p62 controls Toll-like receptor-4-driven aggresome-like induced structure formation and autophagic degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108, 1427–1432 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J. S. et al. Concerted action of p62 and Nrf2 protects cells from palmitic acid-induced lipotoxicity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 466, 131–137 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J. S. et al. p62 prevents carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazine (CCCP)-induced apoptotic cell death by activating Nrf2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 464, 1139–1144 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]