We appreciate the interest and thoughtful comments of Dr Luedde and colleagues on our review, “Death Receptor-Mediated Cell Death and Proinflammatory Signaling in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis.”1 As they have made several seminal insights regarding liver pathobiology, we are flattered that our perspectives on nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), particularly on necroptosis in NASH, triggered their interest. We are happy to continue a friendly scientific dialogue.

They noted, the ideal model of NASH is a matter of intense discussion. We highlight that animals on methionine-choline-deficient (MCD) diet lose weight and lack insulin resistance, which is in direct contrast to humans with NASH. From our perspective, the MCD diet model is not informative regarding the mechanisms of steatohepatitis occurring in the context of the metabolic syndrome, and the use of this model should be discouraged.

It is well established that cell death by necroptosis requires that caspase 8 activity be inhibited or disrupted. This requirement may challenge the biological relevance of necroptosis in human liver disease. Currently, only a few conditions are known that lead to disrupted caspase 8 function in humans.2 For instance, a caspase 8 deficiency state (CEDS), caused by a loss-of-function mutation in the caspase 8 gene, is a very rare genetic disorder of the immune system with no liver phenotype.3, 4 Several viruses and intracellular bacteria may express proteins interfering with caspase 8 activation and can sensitize cells to necroptosis.5 However, this is not a feature of common hepatotropic viruses such as hepatitis C or B viruses. To date, loss of caspase 8 in steatohepatitis has not been reported. Finally, in preclinical studies of NASH, pharmacologic inhibition of caspases have been associated with beneficial effects, including reduced hepatocyte cell death.6, 7, 8

As Dr Luedde and colleagues point out, caspase 8 deletion in intestinal or skin epithelium causes receptor-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase 3 (RIP3)-dependent injury in mice. Similarly, necroptosis may occur in caspase 8−/− mice fed a MCD-diet,9 but these findings cannot be simply extrapolated to a situation where caspase 8 is fully functional, such as during NASH. Studies using caspase 8−/− mice are thus contrived because of the forced caspase 8 deletion. In addition, for interpretation of preclinical studies using caspase 8−/− mice, one should bear in mind that mice possess caspase 8, but humans express caspase 8 and caspase 10, with overlapping functions. Finally, the presence of increased protein levels with RIP3 does not provide proof that necroptosis occurred.10 It should also be noted that RIP3 can form complexes such as the ripoptosome, which induce apoptosis.10

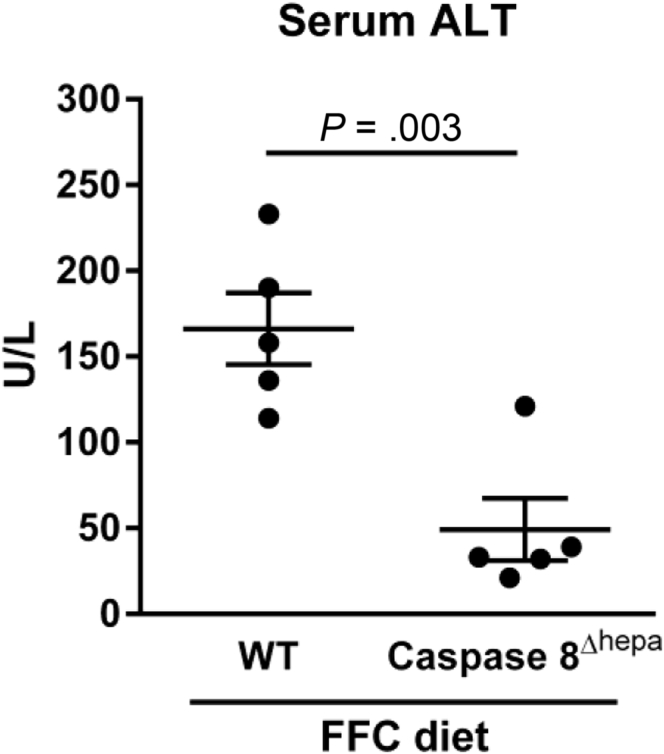

We had the opportunity to experimentally interrogate mice carrying a hepatocyte-specific deletion of caspase 8 (caspase 8Δhepa), which had been generated by Dr Luedde’s colleagues.11 When these mice were fed an established NASH-inducing diet high in saturated fats, fructose, and cholesterol (FFC diet),12 they displayed reduced liver injury compared with wild-type mice as assessed by serum alanine transaminase (ALT) values (Figure 1) and histology (data not shown). Of note, the serum ALT values of these mice were in the range of the ALT values normally seen in healthy mice. The differences between our experience and that of the authors may relate to the NASH model employed. Of note, the FFC diet is the only model that has been demonstrated to recapitulate the chicken-wire pattern of pericellular fibrosis of human NASH occurring in the context of obesity, nutrient excess, and insulin resistance.12

Figure 1.

NASH-induced liver injury is decreased in hepatocyte-specific caspase 8 knockout mice (caspase 8Δhepa). Wild-type mice and mice carrying a hepatocyte-specific deletion of caspase 8 were fed the FFC diet (a NASH-inducing diet high in saturated fats, fructose, and cholesterol) for 3 months, and serum alanine transaminase activity was measured. P value was calculated using unpaired two-tailed t test.

In conclusion, the precise role of necroptosis in human disease remains debatable, and there is not yet convincing evidence that caspase 8 deficiency occurs in any acquired human liver disease. Therefore, we view the likelihood that necroptosis occurs in NASH as unlikely.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest The authors disclose no conflicts.

References

- 1.Hirsova P. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;1:17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2014.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashkenazi A. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2014;30:337–356. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100913-013226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chun H.J. Nature. 2002;419:395–399. doi: 10.1038/nature01063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Su H.C. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2008;28:329–351. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Linkermann A. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:4554–4565. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1310050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barreyro F.J. Liver Int. 2015;35:953–966. doi: 10.1111/liv.12570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anstee Q.M. J Hepatol. 2010;53:542–550. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Witek R.P. Hepatology. 2009;50:1421–1430. doi: 10.1002/hep.23167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gautheron J. EMBO Mol Med. 2014;6:1062–1074. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201403856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pasparakis M. Nature. 2015;517:311–320. doi: 10.1038/nature14191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liedtke C. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:2176–2187. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Charlton M. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2011;301:G825–G834. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00145.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]