Abstract

Hypoxic Pulmonary vasoconstriction (HPV) describes the physiological adaptive process of lungs to preserves systemic oxygenation. It has clinical implications in the development of pulmonary hypertension which impacts on outcomes of patients undergoing cardiothoracic surgery. This review examines both acute and chronic hypoxic vasoconstriction focusing on the distinct clinical implications and highlights the role of calcium and mitochondria in acute versus the role of reactive oxygen species and Rho GTPases in chronic HPV. Furthermore it identifies gaps of knowledge and need for further research in humans to clearly define this phenomenon and the underlying mechanism.

Keywords: Hypoxic Pulmonary Vasoconstriction, Human, Acute hypoxia, Chronic hypoxia, Pulmonary hypertension

INTRODUCTION

Hypoxic Pulmonary Vasoconstriction (HPV) is a fundamental physiological mechanism to redirect the blood from poorly to better-aerated areas of lungs to optimize the ventilation perfusion matching [1]. Persistent hypoxia results in increased pulmonary vascular resistance and right ventricular afterload, which leads to hypoxic pulmonary hypertension (HPH) [2]. HPV was initially thought to be caused by alveolar hypoxia by means of local lung mechanism but recent advances suggest that pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (PASMC) constitute both the sensor and the transducer of the hypoxic signal as well as its contractile effector [3]. A series of experiments performed to explain the HPV on macroscopic and microscopic level has been reported although the underlying mechanism is not clear [4, 5]. However, vast majority of experiments are performed in animals with little data available from humans. Experiments performed on animals are highly dependent on the species studied and therefore generally inapplicable to humans. Therefore new methodologies are needed to understand the human disease biology. In this review we concentrate on the existing evidence for HPV within humans and looking at the pulmonary vascular reactivity to acute and chronic hypoxia and the role of endothelium in vessels size in HPV.

1. OVERVIEW OF THE PULMONARY CIRCULATION

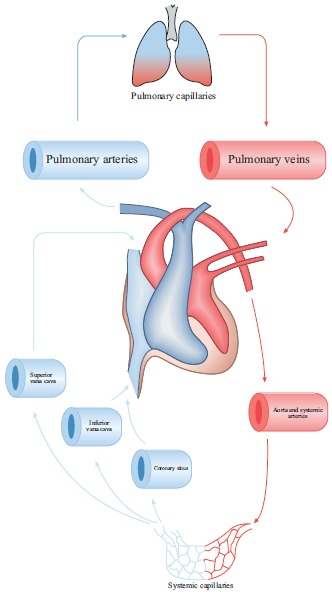

Pulmonary circulation is the segment of cardiovascular system, which carries the blood to and from the lungs. Its primary function is to oxygenate the deoxygenated blood that has returned to the right side of the heart. The oxygenated (oxygen-rich) blood is then delivered to the left side of heart and thus the systemic circulation [6, 7] (Fig. 1).

Fig. (1).

Schematic representation of pulmonary circulation. Red shows oxygen-rich CO2-poor blood. Blue shows oxygen-poor CO2-rich blood.

1.1. Anatomy of Pulmonary Circulation

The vascular wall is made up of three layers; tunica intima (internal layer), tunica media (middle layer) and tunica externa (outer layer) [8, 9]. Endothelial cells are located in the intima and play an important role in regulating vascular function by responding to neurotransmitters, hormones and vasoactive factors [10]. The endothelium and smooth muscle are the vital components for maintenance of arterial tone and regulation of blood pressure. The main purpose of the arteries is to deliver the blood to the organs with high pulse pressure. Arteries can broadly be divided into conducting arteries, conduit arteries (macro-vasculature) and resistance arteries (microvasculature) based on their size, anatomical position and functionality. Conducting arteries are the largest in size and rich in elastic tissues which support the vessels to expand and recoil to accommodate high changes in blood pressure and volume. The aorta, pulmonary artery and carotid arteries are the main examples of conducting arteries [11].

Pulmonary arteries in particular are less muscular, more distensible and compressible compared to their systemic counterpart and resistance pulmonary arterioles contain the most smooth muscle in the pulmonary vasculature [12, 13]. Bronchial circulation is a part of systemic circulation that provides nourishment to the lungs [14]. Pulmonary arteries unlike systemic arteries are always hypoxic as they conduct relatively deoxygenated blood and the gas exchange occurs at capillary level where lungs excrete carbon dioxide [15, 16].

1.2. Regulation of Pulmonary Circulation

Right ventricle and left ventricles are connected in series as is the case for the pulmonary and systemic circulation [17]. The pulmonary circulatory flow is dependent on systemic blood coming to it through right heart as well as the afterload that is determined by the aortic pressure and systemic vascular resistance [18, 19]. In addition to this the pulmonary circulation is also influenced by alveolar compression, gravity, body position and lung volume [20].

The regional ventilation and distribution of blood flow in lung varies from the apex to the base in the upright position [21]. At the apex of the lung the alveolar pressure is higher than the pulmonary artery pressure that results in wasted ventilation. On contrary at the base, the pulmonary pressure is higher than alveolar pressure that causes wasted perfusion [22, 23]. This difference in matching of blood flow to ventilation determines the regional blood flow and disrupts the gas exchange [24, 25].

At tissue level the release or inhibition of certain factors control regional pulmonary blood flow [26].Agonists of smooth muscle contraction such as endothelin increase the pulmonary artery tone [27, 28]. Nitric oxide and acetylcholine are smooth muscle relaxants that are known factors to decrease the pulmonary artery tone [29-31].

The pulmonary circulation is a low pressure, low resistance and high flow circuit and depending on age the average resistance is between 1 – 2.5 mmHg.min.L−1 [32]. Unlike systemic arterioles that dilate in response to hypoxia, the pulmonary arterioles and venules constrict when exposed to hypoxia [33]. This phenomenon is known as hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction that causes diversion of pulmonary blood from poorly ventilated to well-oxygenated areas of lungs to preserve systemic oxygenation [34]. This vasoconstrictive response of HPASMc to hypoxia is further augmented when pulmonary vasculature exposed to hypercapnia and the combined hypoxic and hypercapnic effects are additive not synergistic [35].

However if this short term beneficial role of HPV to facilitate perfusion and ventilation persist or alveolar hypoxia become more widespread or if the hypoxic stimulus is not removed as in intrinsic lung disease, this results in increase in pulmonary resistance and subsequent pulmonary hypertension [36, 37].

2. ACUTE HYPOXIC PULMONARY VASOCONSTRICTION

HPV in humans appears to have several components [38], the first acute phase occur within 5 minute with a mean time constant of 151-160 (+/- 24.8-42) sec followed by a plateau phase of at least 20 minutes [39, 40]. A second phase also known as sustained phase start after a latency period of 30 min and plateau at 2 hours [40] followed by a third chronic phase taking upward of 8 hours [38, 41]. During the sustained hypoxic phase an initial temporary vasodilation response is seen followed by secondary vasoconstriction period [42]. The precise underlying mechanism of HPV is still uncertain but cells in the endothelium and/or smooth muscle cells are involved as HPV can be seen in isolated pulmonary artery [43-45]. Fishman describes the role of nervous system and humoral agents as modulatory rather than primary cause of HPV [46]. Both adrenergic and cholinergic nerve fibres are found in human lung tissue. α adrenergic receptors are predominant both functionally and numerically in lungs as compared to β adrenergic receptors [47]. The adrenergic system only contributes to maintain the initial resting tone needed for HPV while the cholinergic system was found to play no role in the control of pulmonary circulation [48, 49]. This concept of little role of nervous system modulatory role is further strengthened by the fact that HPV still persists in transplanted and denervated lungs [50].

2.1. Role of Calcium in Hypoxic Pulmonary Vasoconstriction

Pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (PASMCs) are found in large arteries as well as in small arterioles [13] and are believed to cause vasoconstriction in response to hypoxia by increasing the intracellular calcium (Ca2+). Intracellular concentration of Ca2+ is mainly regulated by release of sarcoplasmic reticulum stored Ca2+, extracellular Ca2+ influx through voltage gated Ca2+ channels and receptors or store operated Ca2+ channels [51]. PASMCs membrane potential is regulated by voltage gated K+ channels, which control the cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration. Voltage gated K+ channels cause vasoconstriction when exposed to acute hypoxia by increasing cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration and may have a role in some of the components of HPV response [52, 53]. Hypoxia depolarizes the membrane by reducing the outward K+ current and leads to vasoconstriction by increasing the influx of Ca2+ through voltage gated Ca2+ channels.

Michelakis et al. demonstrated that pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells have the ability to sense oxygen and react to hypoxia without any influence from surrounding parenchyma [54]. They also conclude that dissimilarities in systemic and pulmonary circulation response to hypoxia is due to the manifestation of different K+ channels that trigger hyperpolarization and vasodilation in systemic circulation and depolarization and vasoconstriction in pulmonary circulation.

Tang et al. showed that the increase of calcium in PASMCs after acute hypoxia is due to voltage gated calcium channels to some extent but largely due to transient receptor potential [TRP] channels [55]. TRP channels are cation channels that are present in cellular membranes and involved in various cellular activities e.g. pain, touch, temperature and osmolarity [56, 57]. Channel 6 of Canonical subfamily of TRP (TRPC6) are extensively expressed in HPASMc and on activation by its mediators such as epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) induced hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction by increasing intracellular Ca2+ [55].

Vanilloid subtype of transient receptor potential channels (TRPV) also act as sensory channels for heat, pain touch and osmotic stress [58]. TRPV channels are present in endothelium, perivascular nerves and vascular smooth muscle cells and its sub-class TRPV4 is expressed highly in pulmonary endothelial cells and human PASMCs [59]. Acute hypoxia increase the EETs levels that activates the TRPV4, as depletion of EETs attenuated the TRPV6 induced HPV [60]. Goldenberg et al. demonstrated that acute hypoxia induced TRPV4 to trigger HPV by increasing Ca2+ influx and phosphorylation of myosin light chain in human PASMCs [61]. EETs activated TRCP6 and TRPV4 work in parallel to each other and form heteromers when exposed to hypoxia, which increase their surface expression and calcium conductance capacity [62, 63].

Meng et al. demonstrated that arachidonic acid [AA] – a membrane phospholipid, attenuates the hypoxia induced rise in intracellular Ca2+ and related vasoconstriction in human PASMCs [64]. Inhibition of endogenous AA production by diacyglycerol, fatty acid hydrolysis and phospholipase A augments pulmonary vasoconstriction and increase intracellular Ca2+ level through TRP channels, voltage gated Ca2+ channel and Na+ - Ca2+ exchanger.

Beside Ca2+ other important mediators such as reactive oxygen species generated during hypoxia. Under normoxic conditions ROS are predominantly produced in mitochondria of pulmonary cells, suggesting that mitochondria might play a role in HPV.

2.2. Role of Mitochondria/Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) in Hypoxic Pulmonary Vasoconstriction

Mitochondria are essential organelle, which contains iron-sulphur complexes, and proteins within the inner mitochondrial membrane that generate energy through electron shuttle called electron transport chain [65]. During oxygen metabolism stable substances like hydrogen peroxide and unstable toxic substances such as hydroxyl and superoxide radicals are produced. These substances are collectively called reactive oxygen species and are produced from I and III complexes of electron transport chain and NADPH oxidase [66]. Mitochondrial electron transport chain is believed to act as an oxygen sensor and facilitates hypoxic induced vascular smooth muscle cells contraction by controlling different kinases and ion channels through ROS [67]. ROS act as an intercellular and intracellular secondary messenger system and reacts with protein residue like cysteine to regulate different signalling pathway [68].

Mehta et al. established that hypoxia attenuates the production of ROS in human PASMCs [65]. These reduce ROS augments pulmonary vasoconstriction and subsequent pulmonary hypertension through rise in intracellular Ca2+. In addition to PASMCs, coronary artery smooth muscle cells [CASMCs] also show reduction in ROS production during hypoxia. However these cells dilate instead of constricting and the reason for this differential contractile response is not clear. Wang et al. suggested that this differential response to hypoxia in pulmonary and systemic vasculature might be attributed to the way in which ROS regulate their ion channels [69].

Waypa et al. also showed that hypoxia reduces the mitochondrial production of ROS that results in the hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction due to inhibition of voltage gated plasma membrane K+ (KV) channels [70]. Closure of KV channels cause membrane depolarization and subsequent vasoconstriction though increases influx of Ca2+.

Freund-Michel et al. described the role of hypoxia induced mitochondrial alterations and mitochondrial dysfunction that shift the oxidative phosphorylation energy production to glycolysis [71]. The resultant hyperpolarized mitochondria reduced the production of ROS and the metabolic shift to increased glycolysis increased the concentration of non-oxidized sugars, lipids and amino acids that are pre requisite to smooth muscle cells proliferation. Similarly Evans et al. proved that inhibition of oxidative phosphorylation in mitochondria through LKB1 (liver kinase B1) – AMPK (amp activated protein kinase) signalling pathway triggers hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction [72]. This demonstration of hypoxia induced mitochondrial dysfunction in pulmonary artery endothelium, smooth muscle and adventitia of pulmonary hypertension patients suggests that production of targeted mitochondrial therapies will provide effective therapy for this life threatening disease [73, 74]

In contradiction to the above some studies have shown that hypoxia enhanced the production of ROS instead of reducing it. Perez-Vizcaino et al. demonstrated that pulmonary vascular smooth muscle cells augment the production of ROS particularly hydrogen peroxide when exposed to hypoxia [75]. Hypoxia induced ROS increase the intracellular Ca2+ concentration and PASMCs contraction through modulation of protein kinase C, Rho kinases, ryanodine receptors and voltage gated potassium K+ channels. In addition to vascular mitochondria and NADPH oxidases, ROS are also produced from endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), arachidonic acid metabolism and xanthine oxidase.

This controversy regarding ROS during hypoxia might be related to the duration of hypoxia. ROS production by human PASMCs attenuates initially when exposed to brief period of hypoxia [65] but increases subsequently [76].

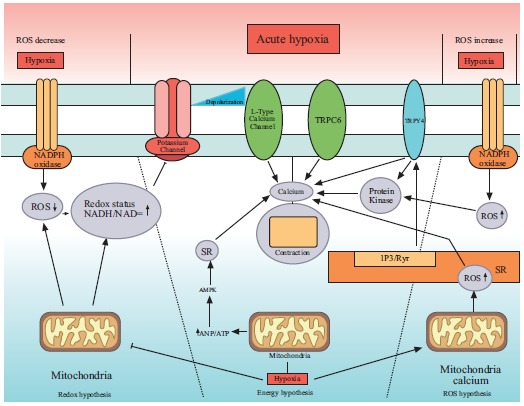

Fig. (2) provides an overview of mechanisms involved in acute hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction.

Fig. (2).

Mechanism of acute hypoxic vasoconstriction in human pulmonary artery. ROS= reactive oxygen species, SR= sarcoplasmic reticulum, TRPC=transient receptor potential channels. Redox hypothesis: Hypoxia decreases the ROS level and cause vasoconstriction through inhibition of K+ channels. Energy hypothesis: hypoxia shifts the energy production cycle and produces more AMP that increases the intracellular Ca2+ through SR. ROS hypothesis: hypoxia augments the production of ROS that cause HPV through SR induced release of Ca2+.

3. CHRONIC HYPOXIC PULMONARY VASOCONSTRICTION

Chronic hypoxia is coupled with refractory vasoconstriction and attenuated NO mediated vasodilation that expedites human PASMc medial hypertrophy and subsequent pulmonary hypertension [77]. Production of reactive oxygen species such as hydrogen peroxide and superoxide and hydroxyl radicals in vascular smooth muscle cells is involved in physiological regulation of vascular tone and vascular remodelling [78].

3.1. Role of ROS and Different Ions in Chronic Hypoxic Pulmonary Vasoconstriction

Wu et al. demonstrated that chronic hypoxia (PO2 = 30 mmHg for 48 h) cause increased ROS level in PASMCs [76]. This increased ROS production induce a pathophysiological response that cause pulmonary vascular remodelling and subsequent chronic hypoxia associated pulmonary hypertension [79]. Similarly Porter et al. in his experiments showed that hypoxia for more than 72 hours significantly induce the hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) production and proliferation of human pulmonary artery endothelial cells (HPAEC) [80]. The hypoxic induced generation of H2O2 activates the arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase (ALOX 5) pathway that induced HPAEC proliferation and vascular remodelling. Pharmacological blockade of ALOX 5 by zileuton or by MK-886 (inhibitors of 5 lipooxygenase activating protein) attenuates hypoxia-induced proliferation of HPAEC.

Platoshyn et al. showed that chronic hypoxia down regulates the mRNA and protein expression of plasma membrane voltage gated potassium (KV) channels that are responsible for regulation of membrane potential and intracellular Ca2+ concentration. The resultant membrane depolarization from inhibition of KV channels results in amplified Ca2+ influx through voltage gated Ca2+ channels in PASMCs and mediates pulmonary vasoconstriction and vascular smooth muscle cells proliferation [81]. Zhao et al. demonstrated that the chronic hypoxia leads to the enhanced expression of Zinc transporter ZIP12 in human endothelial and smooth muscle cells [82]. This intracellular rise of Zinc plays a role in hypoxia induced pulmonary smooth cells proliferation as inhibition of ZIP12 attenuates HPASMc proliferation and development of pulmonary hypertension. Pharmacological development of ZIP12 inhibitor can be a novel treatment module for pulmonary hypertension management.

3.2. Role of Rho A and Rho B in Chronic Hypoxic Pulmonary Vasoconstriction

Rho GTPases is a family of signalling G Proteins, and are regulators of cytoskeletal dynamics, cell migration, cell polarity, neuronal development, vesicle transport and cytokinesis [83]. Rho-A was the first identified member of Rho GTPases family in 1985 [84].

Rho-A with its downstream factor, Rho Kinase (ROCK) mediated multiple cellular functions such as proliferation, contraction, adhesion, migration and gene expression [85]. Rho-A/ROCK signalling pathway is involved in mediating pulmonary artery hypertension, vasoconstriction and vascular remodelling. Inhibition of Rho-A/Rho kinase pathway by sildenafil (cGMP specific phospho-diesterase inhibitor] proves beneficial in pulmonary hypertension patients due to its vasodilatory effects [86].

Rho-B is a protein homologous to Rho-A and in response to hypoxia induced pulmonary vasoconstriction and vascular remodelling by inducing actin-myosin contractility, enhanced endothelial permeability and promotion of cell growth [87]. Rho-B levels significantly increased in human PASMCs when exposed to hypoxia. PDGF/PDGFR signalling pathway is involved in Rho-B mediated PASMCs proliferation as inhibition of PDGF receptor tyrosine kinase by imatinib attenuates the effects of Rho-B. This shows that Rho-B can be a potential therapeutic target to prevent pulmonary hypertension in humans.

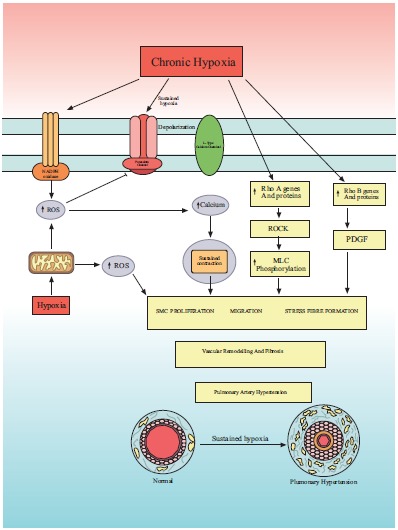

Fig. (3) summarizes the role of ROS and Rho GTPases family in human chronic hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction.

Fig. (3).

Mechanism of chronic hypoxic vasoconstriction in human pulmonary artery. ROS = reactive oxygen species, Rho A and Rho B are members of Rho GTPases family which is a family of G proteins. Chronic hypoxia induced Rho A and Rho b and ROS production that results in smooth muscle cell proliferation, vascular remodelling and ultimately pulmonary artery hypertension.

4. ROLE OF PULMONARY ARTERY ENDOTHELIUM CELLS IN HYPOXIC PULMONARY VASOCONSTRICTION

Vascular endothelium is a layer of specialized cells between vessel lumen and vascular smooth muscle cells and produces several active compounds including vasodilators and vasoconstrictors [88]. Endothelium derived relaxing factor [EDRF-NO], endothelin, lipooxygenase and cyclooxygenase are endothelial vasoactive agents that regulates vascular tone [89].

4.1. Is Endothelium Necessary for HPV?

Hypoxia induced constriction of human pulmonary artery rings is dependent on endothelium was established by Demiryurek et al. as denuding the endothelium markedly abolish the hypoxic vasoconstriction [44]. In contrary to this Ohe et al. demonstrated that endothelium is not needed for hypoxia-induced vasoconstriction. They established that human pulmonary artery strips [2mm in diameter] constrict in response to hypoxia and removal of endothelium instead of abolishing actually enhanced hypoxia-induced vasoconstriction response [45]. The reason for this controversial response claimed in these studies is not very clear.

4.2. Role of Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase (eNOS) in HPV

Endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) is an enzyme that synthesizes nitric oxide (NO) in vascular endothelium [90]. Nitric oxide regulates cellular proliferation, vascular tone, platelet aggregation and leukocyte adhesion [91].

Takemoto et al. demonstrated that prolonged hypoxia induced endothelial injury and diminished the production of eNOS via Rho kinase (ROCK) induced cytoskeletal changes that results in hypoxia induced pulmonary hypertension [92]. Hypoxia-induced ROCK expression results in decrease in eNOS mRNA and protein production in pulmonary artery endothelial cells. However, Krotova et al. have shown that chronic hypoxia induced NO production in human PAECs and this hypoxia-induced production of NO is further enhanced by inhibition of Arginase II [93]. Similarly Beleslin- Cokic et al. showed that hypoxia stimulates NO production, which is independent of hypoxia-induced reduction of eNOS gene expression [94]. This increase in NO production in response to hypoxia, appears to be the compensatory mechanism of the body by inducing the production of other nitric oxide synthase (NOS) enzymes e.g. iNOS.

Chovanec also demonstrated that the endothelium augment the production of NO and superoxide when exposed to chronic hypoxia [95]. The superoxide with NO facilitates the remodelling of pulmonary vasculature that is characterized by tunica media thickening, augmented muscularity and PASMCs proliferation and migration. Superoxide-NO combination marked the onset of collagen cleavage via peroxynitrite release and the resulted collagen fragments induce pulmonary vessels remodelling.

Ghrelin a peptide hormone produced by ghrelinergic cells in gastrointestinal tract is known to have beneficial effects on human pulmonary artery endothelial cell (HPAECs) function. Yang et al. demonstrated that hypoxia for 24 hours risks the viability of endothelial cells and ghrelin can inhibit hypoxia mediated HPAECs dysfunction by increasing NO production and eNOS phosphorylation [96].

Krotova et al. and Yu et al. demonstrated that human PAECs unlike PASMCs do not proliferate when exposed to chronic hypoxia [93, 97]. This reaction can be due to the fragility of endothelial cells under hypoxic conditions as studies show that hypoxia also increases the permeability of HPAECs [87].

Endothelium seems to play a modularity role in HPV and augments the hypoxic induced HPASMc response by modulating their release of vasoconstrictor and vasodilator factors while PASMc remain the main contractile mechanics as explained by Sylvester [98].

5. EFFECT OF VESSEL SIZE ON PULMONARY VASCULATURE REACTIVITY TO HYPOXIA

The effect of hypoxia on human pulmonary artery strips (HPASs) prepared from human pulmonary artery of diameter < 5 mm was examined by Hoshino et al. and established that the vessels constrict in response to hypoxia [43]. This hypoxia induced contractile response is enhanced when HPASs were pre stimulated with histamine. The response was attenuated by depletion of intracellular and extracellular Ca2+ and by HA 1004 – a novel calcium antagonist.

Human pulmonary artery rings - HPARs [2mm in diameter] were demonstrated by Ohe et al. to constrict in response to hypoxia and removal of endothelium enhanced the hypoxia-induced vasoconstriction. Voltage gated Ca2+ channels play a role in hypoxic vasoconstriction and pre stimulation is not a prerequisite [45].

Demiryurek et al. in their study on HPARs showed that hypoxia induced vasoconstriction in both smaller (0.38-0.68 mm) and larger (2.2 – 4.5 mm) diameter vessels under optimal resting conditions. This hypoxia-induced response is enhanced in both sizes HPARSs when rings were pre constricted and removal of endothelium diminished the hypoxic vasocontrictive response [44].

In contrary Ariyaratnam et al. demonstrated that larger HPARs (4 mm diameter) dilate in response to hypoxia and constrict when exposed to hyperoxia (95% O2). This hypoxic vasodilation is independent to nitric oxide, because application of L-NAME had no effect. This study showed hyperoxic vasoconstriction was reliant on voltage gated Ca2+ channels as evidenced by inhibition of vasoconstriction when HPARs treated with nifedipine (Ca2+ channel blocker) [99].

The reason of variation in response to different sized pulmonary vasculature to hypoxia and whether certain degree of pre stimulation is necessary is not clear. More studies need to be performed to confirm whether internal diameter of vessels and pre stimulation alters the reactivity of vessels to hypoxia.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

Hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction is difficult to describe, as the underlying mechanism is complex. More than one mechanism contributes to the overall effect seen in clinical practice. So far most of the research was conducted on animals, which is not necessarily applicable on humans. In addition to this the reactivity of pulmonary vasculature to hypoxia varies between species. Even the experiments that are performed on human shows variability that may be due to variation in pulmonary vasculature reactivity to oxygen between healthy individuals and those who suffered from significant pulmonary disease [100, 101]. It is worth mentioning here that the definition of acute (5min – 12 hours) and chronic (2-7 days) hypoxia and the degree of hypoxia (0% O2–5% O2/5 – 30 mmHg) used for experiments on humans are variable which give rise to discrepancies. We need to agree on a universal definition for acute and chronic hypoxia and for degree of hypoxia to avoid such inconsistencies.

In conclusion the precise mechanism by which hypoxia stimulate pulmonary vasoconstriction has not been completely elucidated.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank Prof Saadeh Suleiman, Prof. Sarah George, Prof. Mahmoud Loubani and Prof. Alyn Morice for their support, supervision and constructive criticism.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ward J.P., McMurtry I.F. Mechanisms of hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction and their roles in pulmonary hypertension: new findings for an old problem. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2009;9(3):287–296. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maggiorini M., Mélot C., Pierre S., Pfeiffer F., Greve I., Sartori C., Lepori M., Hauser M., Scherrer U., Naeije R. High-altitude pulmonary edema is initially caused by an increase in capillary pressure. Circulation. 2001;103(16):2078–2083. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.103.16.2078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang L., Yin J., Nickles H.T., Ranke H., Tabuchi A., Hoffmann J., Tabeling C., Barbosa-Sicard E., Chanson M., Kwak B.R., Shin H.S., Wu S., Isakson B.E., Witzenrath M., de Wit C., Fleming I., Kuppe H., Kuebler W.M. Hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction requires connexin 40-mediated endothelial signal conduction. J. Clin. Invest. 2012;122(11):4218–4230. doi: 10.1172/JCI59176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ariyaratnam P, Loubani M, Morice AH. Hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction in humans. BioMed Res Int. 2013;2013. doi: 10.1155/2013/623684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lumb A.B., Slinger P. Hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction: physiology and anesthetic implications. Anesthesiology. 2015;122(4):932–946. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee Gde.J. Regulation of the pulmonary circulation. Br. Heart J. 1971;33(Suppl.):15–26. doi: 10.1136/hrt.33.Suppl.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Comroe J.H., Jr The main functions of the pulmonary circulation. Circulation. 1966;33(1):146–158. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.33.1.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levick J.R. An introduction to cardiovascular physiology. 5th ed. London: Hodder Arnold; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Welsh D.J., Peacock A.J. Cellular responses to hypoxia in the pulmonary circulation. High Alt. Med. Biol. 2013;14(2):111–116. doi: 10.1089/ham.2013.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galley H.F., Webster N.R. Physiology of the endothelium. Br. J. Anaesth. 2004;93(1):105–113. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeh163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McEniery C.M., Wilkinson I.B., Avolio A.P. Age, hypertension and arterial function. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2007;34(7):665–671. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2007.04657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu P.N., Murphy G.W., Schreiner B.F., Jr, James D.H. Distensibility characteristics of the human pulmonary vascular bed. Study of the pressure-volume response to exercise in patients with and without heart disease. Circulation. 1967;35(4):710–723. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.35.4.710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kay J.M. Comparative morphologic features of the pulmonary vasculature in mammals. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1983;128(2 Pt 2):S53–S57. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1983.128.2P2.S53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deffebach M.E., Charan N.B., Lakshminarayan S., Butler J. The bronchial circulation. Small, but a vital attribute of the lung. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1987;135(2):463–481. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1987.135.2.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gutierrez G., Venbrux A., Ignacio E., Reiner J., Chawla L., Desai A. The concentration of oxygen, lactate and glucose in the central veins, right heart, and pulmonary artery: a study in patients with pulmonary hypertension. Crit. Care. 2007;11(2):R44. doi: 10.1186/cc5739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Redfield A.C., Bock A.V., Meakins J.C. The measurement of the tension of oxygen and carbon dioxide in the blood of the pulmonary artery in man. J. Physiol. 1922;57(1-2):76–81. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1922.sp002044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guazzi M., Arena R. Pulmonary hypertension with left-sided heart disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2010;7(11):648–659. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2010.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guazzi M., Vitelli A., Labate V., Arena R. Treatment for pulmonary hypertension of left heart disease. Curr. Treat. Options Cardiovasc. Med. 2012;14(4):319–327. doi: 10.1007/s11936-012-0185-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lau E.M., Corte T.J. Pulmonary hypertension in 2012: contemporary issues in diagnosis and management. Panminerva Med. 2012;54(1):11–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dawson CA, Krenz GS, Karau KL, Haworth ST, Hanger CC, Linehan JH. Structure-function relationships in the pulmonary arterial tree. J. Appl. Physiol. 1999;86:569–583. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.86.2.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galvin I., Drummond G.B., Nirmalan M. Distribution of blood flow and ventilation in the lung: gravity is not the only factor. Br. J. Anaesth. 2007;98(4):420–428. doi: 10.1093/bja/aem036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Badeer H.S. Gravitational effects on the distribution of pulmonary blood flow: hemodynamic misconceptions. Respiration. 1982;43(6):408–413. doi: 10.1159/000194511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wong D.T., Lee K.J., Yoo S.J., Tomlinson G., Grosse-Wortmann L. Changes in systemic and pulmonary blood flow distribution in normal adult volunteers in response to posture and exercise: a phase contrast magnetic resonance imaging study. J. Physiol. Sci. 2014;64(2):105–112. doi: 10.1007/s12576-013-0298-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.West J.B. Effects of ventilation-perfusion inequality on over-all gas exchange studied in computer models of the lung. J. Physiol. 1969;202(2):116P. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.West J.B. Ventilation-perfusion inequality and overall gas exchange in computer models of the lung. Respir. Physiol. 1969;7(1):88–110. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(69)90071-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fritts H.W., Jr, Harris P., Clauss R.H., Odell J.E., Cournand A. The effect of acetylcholine on the human pulmonary circulation under normal and hypoxic conditions. J. Clin. Invest. 1958;37(1):99–110. doi: 10.1172/JCI103590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maguire J.J., Davenport A.P. ETA receptor-mediated constrictor responses to endothelin peptides in human blood vessels in vitro. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;115(1):191–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb16338.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perez J.F., Sanderson M.J. The contraction of smooth muscle cells of intrapulmonary arterioles is determined by the frequency of Ca2+ oscillations induced by 5-HT and KCl. J. Gen. Physiol. 2005;125(6):555–567. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200409217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Degnim A.C., Nakayama D.K. Nitric oxide and the pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell. Semin. Pediatr. Surg. 1996;5(3):160–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cardell L.O., Hjert O., Uddman R. The induction of nitric oxide-mediated relaxation of human isolated pulmonary arteries by PACAP. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;120(6):1096–1100. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0700992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clauss R.H., Cournand A., Fritts H.W., Jr, Harris P., Odell J.E. Influence of acetylcholine on human pulmonary circulation under normal and hypoxic conditions. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1956;93(1):77–79. doi: 10.3181/00379727-93-22668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Naeije R., Chesler N. Pulmonary circulation at exercise. Compr. Physiol. 2012;2(1):711–741. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c100091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Farhi L.E., Sheehan D.W. Pulmonary circulation and systemic circulation: similar problems, different solutions. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1990;277:579–586. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-8181-5_65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sommer N., Dietrich A., Schermuly R.T., Ghofrani H.A., Gudermann T., Schulz R., Seeger W., Grimminger F., Weissmann N. Regulation of hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction: basic mechanisms. Eur. Respir. J. 2008;32(6):1639–1651. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00013908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Croft Q.P., Formenti F., Talbot N.P., Lunn D., Robbins P.A., Dorrington K.L. Variations in alveolar partial pressure for carbon dioxide and oxygen have additive not synergistic acute effects on human pulmonary vasoconstriction. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e67886. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Voelkel N.F., Mizuno S., Bogaard H.J. The role of hypoxia in pulmonary vascular diseases: a perspective. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2013;304(7):L457–L465. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00335.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Preston I.R. Clinical perspective of hypoxia-mediated pulmonary hypertension. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2007;9(6):711–721. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Swenson E.R. Hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction. High Alt. Med. Biol. 2013;14(2):101–110. doi: 10.1089/ham.2013.1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morrell N.W., Nijran K.S., Biggs T., Seed W.A. Magnitude and time course of acute hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction in man. Respir. Physiol. 1995;100(3):271–281. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(95)00002-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Talbot NP, Balanos GM, Dorrington KL, Robbins PA. Two temporal components within the human pulmonary vascular response to approximately 2h of isocapnic hypoxia. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985) 2005;98(3):1125–1139. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00903.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aaronson P.I., Robertson T.P., Ward J.P. Endothelium-derived mediators and hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2002;132(1):107–120. doi: 10.1016/S1569-9048(02)00053-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weissmann N., Sommer N., Schermuly R.T., Ghofrani H.A., Seeger W., Grimminger F. Oxygen sensors in hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction. Cardiovasc. Res. 2006;71(4):620–629. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hoshino Y, Obara H, Kusunoki M, Fujii Y, Iwai S. Hypoxic contractile response in isolated human pulmonary artery: role of calcium ion. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1988;65(6):2468–2474. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1988.65.6.2468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Demiryurek A.T., Wadsworth R.M., Kane K.A., Peacock A.J. The role of endothelium in hypoxic constriction of human pulmonary artery rings. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1993;147(2):283–290. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/147.2.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ohe M., Ogata M., Katayose D., Takishima T. Hypoxic contraction of pre-stretched human pulmonary artery. Respir. Physiol. 1992;87(1):105–114. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(92)90103-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fishman A.P. Hypoxia on the pulmonary circulation. How and where it acts. Circ. Res. 1976;38(4):221–231. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.38.4.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Porcelli R.J., Viau A.T., Naftchi N.E., Bergofsky E.H. beta-Receptor influence on lung vasoconstrictor responses to hypoxia and humoral agents. J. Appl. Physiol. 1977;43(4):612–616. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1977.43.4.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Joiner P.D., Kadowitz P.J., Hughes J.P., Hyman A.L. NE and ACh responses of intrapulmonary vessels from dog, swine, sheep, and man. Am. J. Physiol. 1975;228(6):1821–1827. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1975.228.6.1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Porcelli R.J., Bergofsky E.H. Adrenergic receptors in pulmonary vasoconstrictor responses to gaseous and humoral agents. J. Appl. Physiol. 1973;34(4):483–488. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1973.34.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Robin E.D., Theodore J., Burke C.M., Oesterle S.N., Fowler M.B., Jamieson S.W., Baldwin J.C., Morris A.J., Hunt S.A., Vankessel A., et al. Hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction persists in the human transplanted lung. Clin. Sci. 1987;72(3):283–287. doi: 10.1042/cs0720283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Catterall W.A., Perez-Reyes E., Snutch T.P., Striessnig J. International Union of Pharmacology. XLVIII. Nomenclature and structure-function relationships of voltage-gated calcium channels. Pharmacol. Rev. 2005;57(4):411–425. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.4.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sweeney M., Yuan J.X. Hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction: role of voltage-gated potassium channels. Respir. Res. 2000;1(1):40–48. doi: 10.1186/rr11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lai N., Lu W., Wang J. Ca(2+) and ion channels in hypoxia-mediated pulmonary hypertension. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2015;8(2):1081–1092. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Michelakis E.D., Archer S.L., Weir E.K. Acute hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction: a model of oxygen sensing. Physiol. Res. 1995;44(6):361–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tang C., To W.K., Meng F., Wang Y., Gu Y. A role for receptor-operated Ca2+ entry in human pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells in response to hypoxia. Physiol. Res. 2010;59(6):909–918. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.931875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Clapham D.E. TRP channels as cellular sensors. Nature. 2003;426(6966):517–524. doi: 10.1038/nature02196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yin J., Kuebler W.M. Mechanotransduction by TRP channels: general concepts and specific role in the vasculature. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2010;56(1):1–18. doi: 10.1007/s12013-009-9067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Clapham D.E., Runnels L.W., Strübing C. The TRP ion channel family. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2001;2(6):387–396. doi: 10.1038/35077544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Baylie R.L., Brayden J.E. TRPV channels and vascular function. Acta Physiol. (Oxf.) 2011;203(1):99–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2010.02217.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Keserü B., Barbosa-Sicard E., Popp R., Fisslthaler B., Dietrich A., Gudermann T., Hammock B.D., Falck J.R., Weissmann N., Busse R., Fleming I. Epoxyeicosatrienoic acids and the soluble epoxide hydrolase are determinants of pulmonary artery pressure and the acute hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstrictor response. FASEB J. 2008;22(12):4306–4315. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-112821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Goldenberg N.M., Wang L., Ranke H., Liedtke W., Tabuchi A., Kuebler W.M. TRPV4 is required for hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction. Anesthesiology. 2015;122(6):1338–1348. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Flockerzi V., Nilius B. TRPs: truly remarkable proteins. Handbook Exp. Pharmacol. 2014;222:1–12. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-54215-2_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ma X., Cao J., Luo J., Nilius B., Huang Y., Ambudkar I.S., Yao X. Depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores stimulates the translocation of vanilloid transient receptor potential 4-c1 heteromeric channels to the plasma membrane. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2010;30(11):2249–2255. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.212084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Meng F., To W.K., Gu Y. Inhibition effect of arachidonic acid on hypoxia-induced [Ca(2+)](i) elevation in PC12 cells and human pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2008;162(1):18–23. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mehta J.P., Campian J.L., Guardiola J., Cabrera J.A., Weir E.K., Eaton J.W. Generation of oxidants by hypoxic human pulmonary and coronary smooth-muscle cells. Chest. 2008;133(6):1410–1414. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-2984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Weir E.K., López-Barneo J., Buckler K.J., Archer S.L. Acute oxygen-sensing mechanisms. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;353(19):2042–2055. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Michelakis E.D., Rebeyka I., Wu X., Nsair A., Thébaud B., Hashimoto K., Dyck J.R., Haromy A., Harry G., Barr A., Archer S.L. O2 sensing in the human ductus arteriosus: regulation of voltage-gated K+ channels in smooth muscle cells by a mitochondrial redox sensor. Circ. Res. 2002;91(6):478–486. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000035057.63303.D1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wong C.M., Cheema A.K., Zhang L., Suzuki Y.J. Protein carbonylation as a novel mechanism in redox signaling. Circ. Res. 2008;102(3):310–318. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.159814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang Y.X., Zheng Y.M. Role of ROS signaling in differential hypoxic Ca2+ and contractile responses in pulmonary and systemic vascular smooth muscle cells. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2010;174(3):192–200. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Waypa GB, Schumacker PT. Hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction: redox events in oxygen sensing. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2005;98(1):404–414. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00722.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Freund-Michel V., Khoyrattee N., Savineau J.P., Muller B., Guibert C. Mitochondria: roles in pulmonary hypertension. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2014;55:93–97. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2014.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Evans A.M., Lewis S.A., Ogunbayo O.A., Moral-Sanz J. Modulation of the LKB1-AMPK signalling pathway underpins hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction and pulmonary hypertension. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2015;860:89–99. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-18440-1_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Paulin R., Michelakis E.D. The metabolic theory of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circ. Res. 2014;115(1):148–164. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.301130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sutendra G., Michelakis E.D. The metabolic basis of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Cell Metab. 2014;19(4):558–573. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Perez-Vizcaino F., Cogolludo A., Moreno L. Reactive oxygen species signaling in pulmonary vascular smooth muscle. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2010;174(3):212–220. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wu W., Platoshyn O., Firth A.L., Yuan J.X. Hypoxia divergently regulates production of reactive oxygen species in human pulmonary and coronary artery smooth muscle cells. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2007;293(4):L952–L959. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00203.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Konik E.A., Han Y.S., Brozovich F.V. The role of pulmonary vascular contractile protein expression in pulmonary arterial hypertension. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2013;65:147–155. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gupte S.A., Rupawalla T., Phillibert D., Jr, Wolin M.S. NADPH and heme redox modulate pulmonary artery relaxation and guanylate cyclase activation by NO. Am. J. Physiol. 1999;277(6 Pt 1):L1124–L1132. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.277.6.L1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lyle A.N., Griendling K.K. Modulation of vascular smooth muscle signaling by reactive oxygen species. Physiology (Bethesda) 2006;21:269–280. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00004.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Porter K.M., Kang B.Y., Adesina S.E., Murphy T.C., Hart C.M., Sutliff R.L. Chronic hypoxia promotes pulmonary artery endothelial cell proliferation through H2O2-induced 5-lipoxygenase. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e98532. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Platoshyn O., Yu Y., Golovina V.A., McDaniel S.S., Krick S., Li L., Wang J.Y., Rubin L.J., Yuan J.X. Chronic hypoxia decreases K(V) channel expression and function in pulmonary artery myocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2001;280(4):L801–L812. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.280.4.L801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zhao L., Oliver E., Maratou K., Atanur S.S., Dubois O.D., Cotroneo E., Chen C.N., Wang L., Arce C., Chabosseau P.L., Ponsa-Cobas J., Frid M.G., Moyon B., Webster Z., Aldashev A., Ferrer J., Rutter G.A., Stenmark K.R., Aitman T.J., Wilkins M.R. The zinc transporter ZIP12 regulates the pulmonary vascular response to chronic hypoxia. Nature. 2015;524(7565):356–360. doi: 10.1038/nature14620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Heasman S.J., Ridley A.J. Mammalian Rho GTPases: new insights into their functions from in vivo studies. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9(9):690–701. doi: 10.1038/nrm2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Madaule P., Axel R. A novel ras-related gene family. Cell. 1985;41(1):31–40. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90058-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jaffe A.B., Hall A. Rho GTPases: biochemistry and biology. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2005;21:247–269. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.020604.150721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ghofrani H.A., Wiedemann R., Rose F., Schermuly R.T., Olschewski H., Weissmann N., Gunther A., Walmrath D., Seeger W., Grimminger F. Sildenafil for treatment of lung fibrosis and pulmonary hypertension: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360(9337):895–900. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11024-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wojciak-Stothard B., Zhao L., Oliver E., Dubois O., Wu Y., Kardassis D., Vasilaki E., Huang M., Mitchell J.A., Harrington L.S., Prendergast G.C., Wilkins M.R. Role of RhoB in the regulation of pulmonary endothelial and smooth muscle cell responses to hypoxia. Circ. Res. 2012;110(11):1423–1434. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.264473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sumpio B.E., Riley J.T., Dardik A. Cells in focus: endothelial cell. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2002;34(12):1508–1512. doi: 10.1016/S1357-2725(02)00075-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ward J.P., Robertson T.P. The role of the endothelium in hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction. Exp. Physiol. 1995;80(5):793–801. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1995.sp003887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Marsden P.A., Schappert K.T., Chen H.S., Flowers M., Sundell C.L., Wilcox J.N., Lamas S., Michel T. Molecular cloning and characterization of human endothelial nitric oxide synthase. FEBS Lett. 1992;307(3):287–293. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80697-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Förstermann U., Münzel T. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase in vascular disease: from marvel to menace. Circulation. 2006;113(13):1708–1714. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.602532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Takemoto M., Sun J., Hiroki J., Shimokawa H., Liao J.K. Rho-kinase mediates hypoxia-induced downregulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Circulation. 2002;106(1):57–62. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000020682.73694.AB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Krotova K., Patel J.M., Block E.R., Zharikov S. Hypoxic upregulation of arginase II in human lung endothelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2010;299(6):C1541–C1548. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00068.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Beleslin-Čokić B.B., Cokić V.P., Wang L., Piknova B., Teng R., Schechter A.N., Noguchi C.T. Erythropoietin and hypoxia increase erythropoietin receptor and nitric oxide levels in lung microvascular endothelial cells. Cytokine. 2011;54(2):129–135. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2011.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chovanec M. Role of reactive oxygen species and nitric oxide in development of the hypoxic pulmonary hypertension. Cesk. Fysiol. 2013;62(1):4–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Yang D., Liu Z., Zhang H., Luo Q. Ghrelin protects human pulmonary artery endothelial cells against hypoxia-induced injury via PI3-kinase/Akt. Peptides. 2013;42:112–117. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yu L., Hales C.A. Hypoxia does neither stimulate pulmonary artery endothelial cell proliferation in mice and rats with pulmonary hypertension and vascular remodeling nor in human pulmonary artery endothelial cells. J. Vasc. Res. 2011;48(6):465–475. doi: 10.1159/000327005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sylvester J.T., Shimoda L.A., Aaronson P.I., Ward J.P. Hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction. Physiol. Rev. 2012;92(1):367–520. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00041.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ariyaratnam P, Loubani M, Bennett R, et al. Hyperoxic vasoconstriction of human pulmonary arteries: a novel insight into acute ventricular septal defects. ISRN Cardiol. 2013;2013:4. doi: 10.1155/2013/685735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Cases E., Vila J.M., Medina P., Aldasoro M., Segarra G., Lluch S. Increased responsiveness of human pulmonary arteries in patients with positive bronchodilator response. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;119(7):1337–1340. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb16043.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Peinado V.I., París R., Ramírez J., Roca J., Rodriguez-Roisin R., Barberà J.A. Expression of BK(Ca) channels in human pulmonary arteries: relationship with remodeling and hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction. Vascul. Pharmacol. 2008;49(4-6):178–184. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]