Abstract

The Gram-positive bacterium Streptococcus pneumoniae causes severe disease globally. Vaccines that prevent S. pneumoniae infections induce antibodies against epitopes within the bacterial capsular polysaccharide (CPS). A better immunological understanding of the epitopes that protect from bacterial infection requires defined oligosaccharides obtained by total synthesis. The key to the synthesis of the S. pneumoniae serotype 12F CPS hexasaccharide repeating unit that is not contained in currently used glycoconjugate vaccines is the assembly of the trisaccharide β-D-GalpNAc-(1→4)-[α-D-Glcp-(1→3)]-β-D-ManpNAcA, in which the branching points are equipped with orthogonal protecting groups. A linear approach relying on the sequential assembly of monosaccharide building blocks proved superior to a convergent [3 + 3] strategy that was not successful due to steric constraints. The synthetic hexasaccharide is the starting point for further immunological investigations.

Keywords: carbohydrate antigen, glycosylation, oligosaccharides, Streptococcus pneumoniae, total synthesis

Introduction

Streptococcus pneumoniae is a Gram-positive bacterium that colonizes the upper respiratory tract and causes life-threatening pulmonary diseases as well as infections of the brain, the middle ear and the sinuses [1–6]. Twenty-three of the more than ninety S. pneumoniae serotypes, which differ in the capsular polysaccharides (CPS) that surround them, are responsible for about 90% of infections worldwide [7]. The licensed polysaccharide vaccine Pneumovax 23 contains serotype 12F but is not efficacious in young children or elderly people, those at highest risk. The carbohydrate conjugate vaccines Prevanar13™ and Synflorix™ [8–11] are based on CPS-carrier protein constructs and contain thirteen or ten S. pneumoniae serotypes, respectively, but not 12F [12–13]. The S. pneumoniae serotypes 12A [14] and 12F [15] combined account for more than 4% of pneumococcal disease [16], whereby 12F (Figure 1) dominates with 85% [17]. In order to improve current glycoconjugate vaccines additional serotypes such as 12F should be included in next-generation preparations [18].

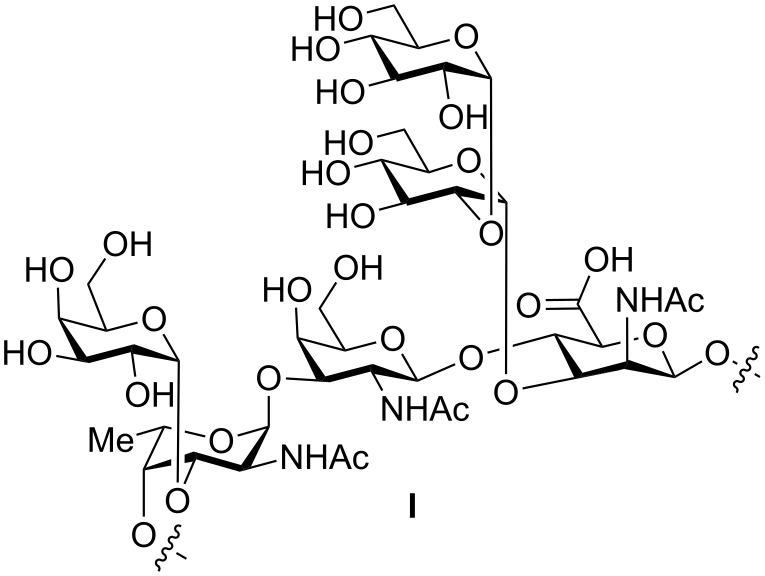

Figure 1.

Structure of the S. pneumoniae serotype 12F capsular polysaccharide repeating unit [15].

Synthetic oligosaccharides are important tools for the identification of vaccine epitopes and have been the key to the creation of monoclonal antibodies that serve as tools for vaccine design [19] and for the detection of pathogenic bacteria such as Bacillus anthracis [20–21]. S. pneumoniae 12F CPS consists of hexasaccharide repeating units containing the [→4)-α-L-FucpNAc-(1→3)-β-D-GalpNAc-(1→4)-β-D-ManpNAcA-(1→] polysaccharide backbone with a disaccharide branch at C3 of β-D-ManpNAcA and C3 of α-L-FucpNAc [15]. We established a total synthesis of the hexasaccharide repeat unit as a first step toward a detailed immunological analysis of S. pneumoniae 12F.

Results and Discussion

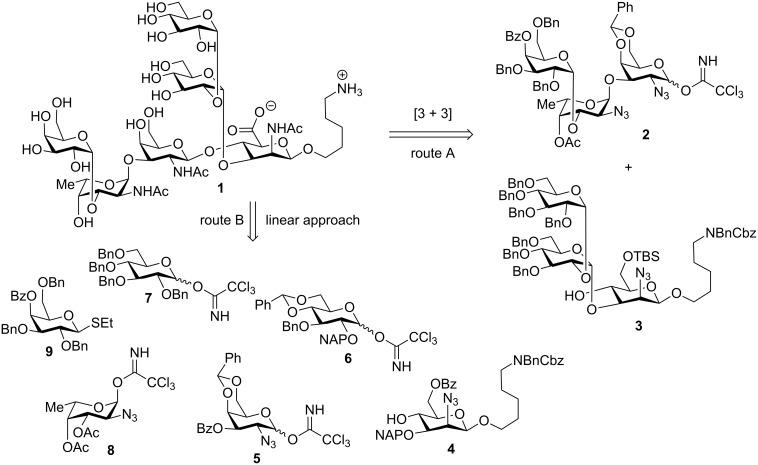

Retrosynthetic analysis. Initially, a convergent [3 + 3] synthesis of the repeating unit hexasaccharide 1 was envisioned. The union of trisaccharides 2 and 3 (Scheme 1, route A) was identified as the key step. The outcome of this late-stage block coupling was deemed risky considering the poor nucleophilicity of the C4 hydroxy group of the β-mannosazide in 3 combined with steric bulk around the acceptor. Trisaccharides 2 and 3 can be derived from differentially protected common building blocks that carry tert-butyldimethylsilyl (TBS), benzoate (Bz) or acetate (Ac) ester and 2-naphthylmethyl (NAP) protecting groups that can be removed sequentially to allow for glycosylation of the liberated hydroxy groups. Formation of the β-mannosazide glycoside containing a protected C5 amino linker that serves in the final product as an attachment point for glycan array surfaces or carrier proteins was central to the assembly of trisaccharide 3. To avoid a challenging and often unselective β-mannoside formation step we resorted to glucose–mannose conversion by inversion of the C2 stereocenter following selective installation of a trans-glucosidic linkage. Differentially protected thioglucoside 11 [22] is equipped with a participating C2 levulinyl ester that is replaced by an axial azido group following β-glucoside formation [23].

Scheme 1.

Retrosynthetic analyses of the S. pneumoniae hexasaccharide 1.

Alternatively, a linear synthetic strategy in which the sterically hindered C4 hydroxy group would be glycosylated first, followed by the C3 hydroxy group of β-mannosazide building block 4, was designed in case the convergent approach proved unsuccessful (Scheme 1, route B).

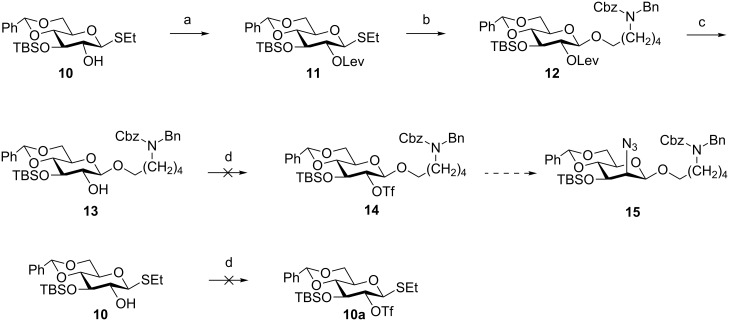

Building block synthesis. The accessibility of differentially protected monosaccharide building blocks is a prerequisite for the successful total synthesis of any complex glycan. The synthesis of the mannosazide building block was the first challenge to be addressed. Installation of a C2-participating levulinyl ester protecting group ensured selective formation of the trans-glycoside upon activation of 11 by NIS/TfOH in the presence of the C5 linker to produce glucoside 12 in 70% yield [24]. Cleavage of the C2 levulinyl ester of 12 by treatment with hydrazine acetate furnished 13, which was to be carried forward into the C2 inversion step. Conversion of 13 to the corresponding C2 triflate upon treatment with triflic anhydride in pyridine was not successful. Even model thioglycoside 10 failed to react to the corresponding glycosyl triflate under similar conditions (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Attempted synthesis of mannosazide building block 15. Reagents and conditions: (a) levulinic acid, DCC, DMAP, CH2Cl2, 82%; (b) NIS, TfOH, HO(CH2)5NBnCbz, CH2Cl2, −20 °C, 70%; (c) N2H4, AcOH, pyridine, CH2Cl2, 70%; (d) Tf2O, pyridine, CH2Cl2, 0 °C to rt.

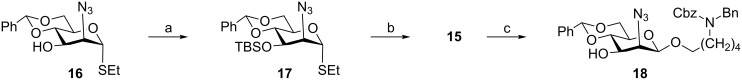

The problems associated with the lengthy and low yielding synthetic sequence prompted us to explore a different approach to obtain the key mannosazide building block (Scheme 3). Partially protected mannosazide thioglycoside 16 was prepared in seven steps from α-O-methylglucose following a published procedure [25]. Silylation of the C3 hydroxy group furnished thioglycoside 17. Glycosylation of the C5 linker by activation of 17 using NIS/TfOH as the promoter at −20 °C produced mainly β-mannoside 15 (4:1 β:α) [26]. The identity of the β-isomer was confirmed by NMR analysis (1JCH β = 159.0 Hz, see Supporting Information File 1). Cleavage of the silyl ether by TBAF treatment of 15 afforded the β-mannosazide building block 18.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of mannosazide building block 18. Reagents and conditions: (a) TBSCl, imidazole, DCM, 0 °C to rt, 85%; (b) NIS, TfOH, HO(CH2)5NBnCbz, CH2Cl2, −20 °C, 61%; (c) TBAF, THF, 0 °C, 80%.

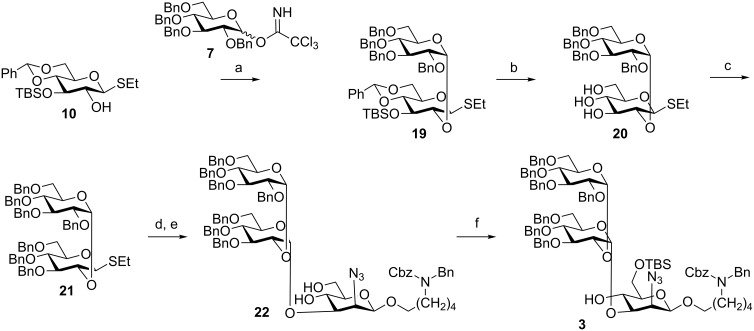

Convergent [3 + 3] synthesis. Synthesis of the reducing-end trisaccharide 3 (Scheme 1) commenced with the assembly of the α-1→2 linked diglucoside 19 by union of the monosaccharide building blocks 10 and 7 [27] in a dichloromethane–ether (enables alpha selectivity) mixture in 56% yield (Scheme 4). Removal of the silyl ether and benzylidene groups of 19 yielded triol 20 before benzylation afforded disaccharide thioglycoside building block 21. Activation of disaccharide 21 resulted in the glycosylation of mannosazide acceptor 18 (Scheme 3) to form the corresponding α-linked trisaccharide, which, subsequent to removal of the 4,6-benzylidene group under acidic conditions, provided diol 22 that was in turn converted into reducing-end trisaccharide 3 by selective placement of a TBS ether [28] on the primary alcohol (Scheme 4).

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of the reducing-end trisaccharide 3. Reagents and conditions: (a) TMSOTf, (CH3CH2)2O/CH2Cl2 (4:1), −20 °C, α/β = 4:1, 70%; (b) p-TsOH, CH3OH/CH2Cl2 (1:1), rt, 70%; (c) NaH, benzyl bromide, THF/DMF (1:1), 0 °C to rt, 90%; (d) 18, NIS, TfOH, (CH3CH2)2O/CH2Cl2, (4:1), −20 °C, 61%; (e) p-TsOH, CH3OH, rt, 90%; (f) TBSCl, imidazole, CH2Cl2, rt, 93%.

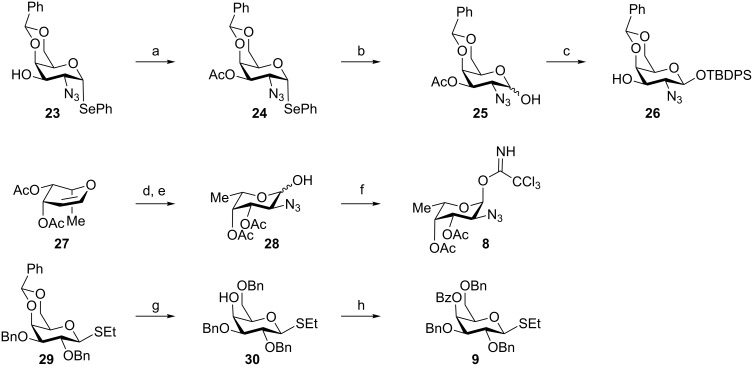

With reducing-end trisaccharide 3 in hand, we turned our attention to the synthesis of trisaccharide 2, which required the availability of three differentially protected monosaccharide building blocks: 8, 9 and 26 (Scheme 5). Protected building block 26 was obtained in four steps from known galactosylazide selenide 23 [29]. Acetylation of the C3 hydroxy group of 23 furnished fully differentially protected selenoglycoside 24 in 82% yield. Hydrolysis of the selenoglycoside using NIS in aqueous THF produced hemiacetal 25 that was silylated prior to selective saponification of the C3 O-acetate to yield building block 26 (Scheme 5).

Scheme 5.

Synthesis of monosaccharide building blocks 8, 9 and 26. Reagents and conditions: (a) acetic anhydride, pyridine, CH2Cl2, rt, 18 h, 82%; (b) NIS, THF/H2O (1:1), rt; (c) 1) TBDPSCl, imidazole, DMF, rt; 2) NaOMe, MOH, rt, 68% over two steps; (d) (PhSe)2, BAIB, NaN3, CH2Cl2, rt, 24 h; (e) NIS, THF/H2O (1:1), rt, 80% over two steps; (f) CCl3CN, DBU, CH2Cl2, 0 °C to rt, 2 h, 72%; (g) TES, TFA, CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 6 h; (h) benzoyl chloride, pyridine, rt, 18 h, 80% over two steps.

Fucosazide building block 8 was derived from diacetyl fucal 27 that in turn was prepared in two steps from L-fucose [30]. Azido-selenation of 27 and hydrolysis of the seleno fucosazide with NIS in aqueos THF [31] provided hemiacetal 28, which was subsequently converted to the fucosyl trichloroacetimidate building block 8 (Scheme 5). Galactosyl thioglycoside 9 was prepared from D-galactose following published procedures [32]. Reductive opening of the benzylidene acetal of known galactosyl thioglycoside 29 [33] with triethylsilane [34] in TFA/CH2Cl2 liberated the C4 hydroxy group of 30, which was subsequently benzoylated to ensure remote participation in 9 for the preferential formation of cis-glycosides (Scheme 5) [35].

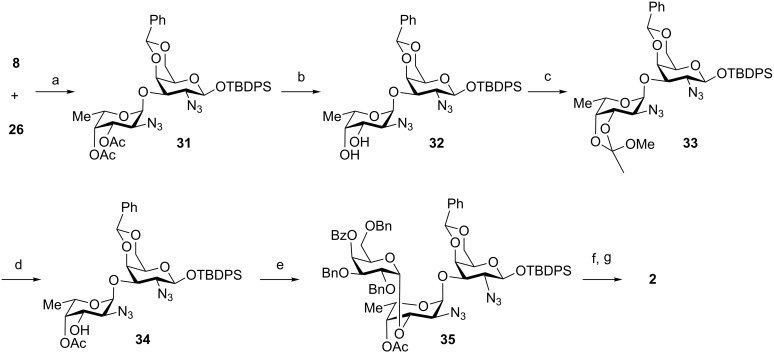

With the three building blocks 8, 9 and 26 in hand, the assembly of the non-reducing end trisaccharide 2 commenced. The union of 8 and 26 produced the α-linked disaccharide 31 in 74% yield and excellent α-selectivity due to remote participation of the C2 and C3 acetate esters present in the fucosazide donor (Scheme 6). Preparation of the site for the downstream glycosylation, the C3 hydroxy group in the fucosazide moiety, to obtain 35, required several protecting group manipulation steps: cleavage of the two acetate esters of 31 to produce diol 32 was followed by the reaction with trimethyl orthoacetate to provide the ortho-ester 33, which was regioselectively opened under acidic conditions to afford disaccharide acceptor 34 containing a C3 hydroxy group [28]. Glycosylation of disaccharide 34 using galactose building block 9, activated by NIS/triflic acid, produced trisaccharide 35 with high α-selectivity by virtue of the C4-participating benzoyl ester protecting group of 9 [36]. Trisaccharide 35 was transformed into a glycosylating agent by removal of the anomeric TBDPS silyl ether using HF-pyridine and subsequent treatment with trichloroacetonitrile in the presence of catalytic amounts of DBU to afford glycosyl trichloroacetimidate trisaccharide 2 (Scheme 1).

Scheme 6.

Synthesis of the non-reducing end trisaccharide 2. Reagents and conditions: (a) TMSOTf, CH2Cl2, −30 °C, 74%; (b) NaOMe (0.5 M in MeOH), MeOH, rt; (c) trimethyl orthoacetate, p-TsOH, toluene; (d) 80% AcOH, rt, 71% over three steps; (e) 9, NIS, TMSOTf, dioxane/toluene (3:1), −10 °C, 54%; (f) HF-pyridine, THF, 0 °C; (g) CCl3CN, DBU, CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 57% over two steps.

With trisaccharide fragments 2 and 3 in hand, the convergent [3 + 3] approach (Scheme 1, route A) to the synthesis of the repeating unit hexasaccharide 36 (Scheme 7) was attempted. The union of trisaccharides 2 and 3 using TMSOTf in acetonitrile as the activator did not yield the desired hexasaccharide 36. Instead, trisaccharide acceptor 3 missing its C6 silyl ether protecting group 38 was recovered. The undesired outcome of this coupling step likely resulted from the poor nucleophilicity of 3 rather than a lack of reactivity of trisaccharide glycosylating agent 2, as demonstrated by an experiment in which model monosaccharide 37 [29] also failed to react with trisaccharide acceptor 3 and recovered 38 (Scheme 7).

Scheme 7.

Attempted synthesis of hexasaccharide repeating unit 36 via a convergent [3 + 3] glycosylation strategy and exploratory control experiments. A) Failed [3 + 3] glycosylation; B) failed model [1 + 3] glycosylation; C) low yielding model coupling of two monosaccharides.

In order to better understand the formation of the key disaccharide GalNAc→ManNAcA, a model glycosylation involving mannosazide 4 (Scheme 7, prepared in four steps from 16, see Supporting Information File 1) was explored. Differentially protected mannosazide 4 was successfully glycosylated using building blocks 5 or 37 to yield the corresponding disaccharide in 21% and 37% yield, respectively. The failure of the [3 + 3] coupling to produce hexasaccharide 36 was apparently a result of the poor nucleophilicity of the C4 hydroxy group in 3 rather than of problems associated with the glycosylating agents. The presence of a disaccharide appendage at the C3 position as well as a bulky TBS silyl ether at C6 may block the C4 hydroxy group.

The β-selectivity of glycosylations using glycosylating agents 5 and 37 even in acetonitrile was rather poor. Apparently, the “nitrile effect” [37–38] is partially overruled by the participating nature of the C3 ester protecting groups Ac/Bz that leads to a preference for the cis-glycosidic α-linked product.

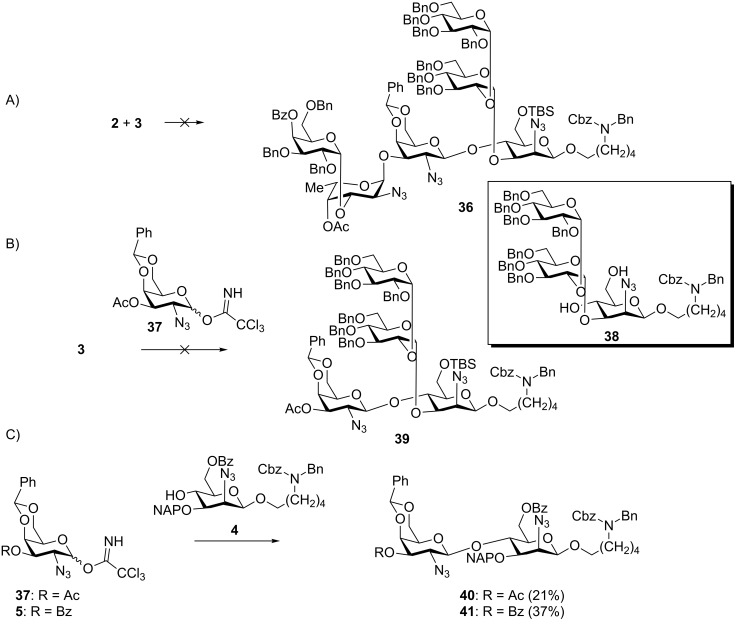

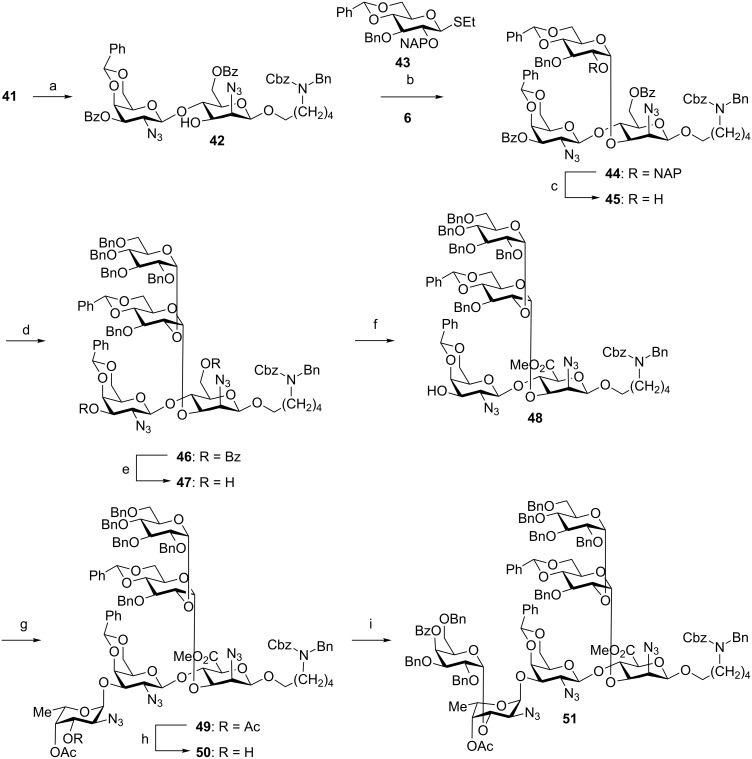

Linear total synthesis of 12F repeating unit hexasaccharide 1. The failure of the convergent [3 + 3] total synthesis approach prompted us to retreat to the linear avenue (Scheme 1, route B) towards the target oligosaccharide in order to avoid the sterically demanding late-stage glycosylation. Differentially protected mannosazide 4 served as the starting point for stepwise assembly from the reducing to the non-reducing end (Scheme 8). Union of 4 and 5 (Scheme 7) produced disaccharide 41 as the key intermediate, the naphthyl protecting group of which was cleaved in 70% yield using DDQ [37] to afford 42. Thioglycoside 43 failed to react with disaccharide 42 to furnish the desired trisaccharide 44. Considering a potential “mismatch” [38] between the thioglycoside glycosylating agent and the acceptor [39–40] we explored whether the glucosyl trichloroacetimidate donor 6 (Scheme 1) would be more suitable. Indeed, glycosylation of disaccharide 42 with building block 6 using TMSOTf as the activator proceeded to produce trisaccharide 44 in 65% yield.

Scheme 8.

Linear assembly of fully protected hexasaccharide 51. Reagents and conditions: (a) DDQ, CH2Cl2/MeOH (9:1), rt, 70%; (b) 43, NIS, TfOH, CH2Cl2, −20 °C (no reaction) or 6, TMSOTf, Et2O/CH2Cl2 (4:1), −20 °C (65%); (c) DDQ, CH2Cl2/MeOH (9:1), rt, 55%; (d) 7, TMSOTf, Et2O/CH2Cl2 (4:1), −20 °C, 62%; (e) NaOMe (0.5 M in MeOH), THF/MeOH (1:1), rt, 90%; (f) i. TEMPO, BAIB, CH2Cl2/H2O (4:1), rt; ii. MeI, K2CO3, DMF, rt, 35% over two steps; (g) 8, TMSOTf, CH2Cl2, −20 °C, 77%; (h) i. NaOMe (0.5 M in MeOH), THF/MeOH (1:1); ii. trimethyl orthoacetate, p-TsOH, toluene; iii. 80% AcOH, rt, 27% over three steps; (i) 9, NIS, TMSOTf, dioxane/toluene (3:1), −10 °C to 0 °C, 54%.

Removal of the C2 naphthyl ether using DDQ provided acceptor 45, which in turn was reacted with glucosyl thioglycoside 7 in the presence of NIS and TfOH to produce α-linked tetrasaccharide 46 in 62% yield (Scheme 8). At this stage, the 2-azidomannose moiety of 46 was converted to the corresponding mannosaminuronic acid by cleaving the C6 benzoate ester using sodium methoxide in methanol and selective oxidation of the primary alcohol of 47 using BAIB/TEMPO. Tetrasaccharide acceptor 48 was obtained by esterification of the carboxylic acid under basic conditions using methyl iodide in 32% yield over three steps [41]. Next, TMSOTf activation of fucosyl trichloroacetimidate 8 (Scheme 1) catalyzed the glycosylation of methyl uronate 48 to afford pentasaccharide 49 exclusively as the α-isomer by virtue of remote participation of the 3-O-acetate group. In anticipation of the final glycosylation, the fucosazide moiety of 49 was converted into acceptor 50. The desired hexasaccharide 51 was obtained as the α-anomer in 54% yield by coupling galactose building block 9 (Scheme 1) to pentasaccharide 50 using NIS/TfOH in a mixture of toluene/dioxane. Again, the C4 benzoate ester of 9 ensured high selectivity for the desired cis-glycosidic linkage.

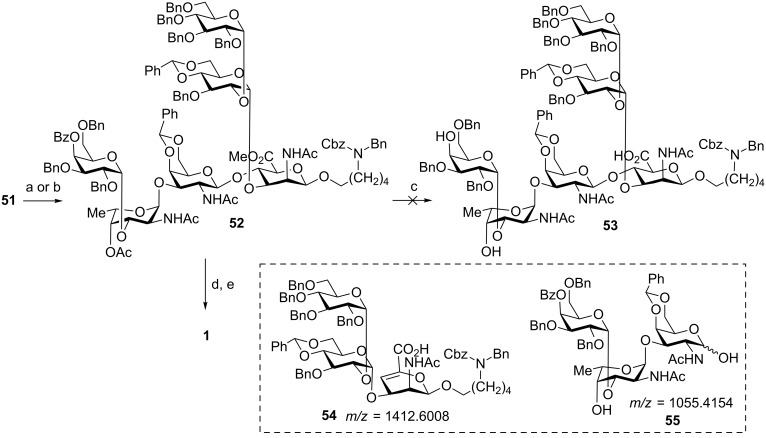

Global deprotection commenced with the conversion of the three azide groups present in compound 51 into NHAc groups in a single step using thioacetic acid in pyridine [42] afforded triacetamide 52 in 65% yield; it is important to note that Zn-mediated reduction of 51 led to decomposition of the substrate. Ester saponification of 52 employing sodium methoxide in methanol yielded none of the desired product 53 but rather the tentatively assigned β-elimination products 54 and 55. Furthermore, an attempt at employing a more nucleophilic and less basic reagent such as a lithium hydroxide/hydrogen peroxide mixture did not provide relief from the problem, but instead also produced a mixture of undesired products. Adjustments in the sequence of deprotection steps by first carrying out hydrogenolysis using Pd/C in a mixture of AcOH/H2O/t-BuOH prior to ester hydrolysis using LiOH/H2O2 enabled the hexasaccharide 1 to be obtained in 37% yield (Scheme 9).

Scheme 9.

Global deprotection to furnish S. pneumonia serotype 12F repeating unit hexasaccharide 1. Reagents and conditions: (a) thioacetic acid, pyridine, rt, 65%; (b) Zn, AcOH/Ac2O/THF, Cu2SO4 (aq, decomposed); saponification conditions that lead to β-elimination (c) i. NaOMe (0.5 M in MeOH) in MeOH, ii. NaOH (4 M, 2 M, 1 M, 0.5 M, 0.1 M) solution in THF, iii. H2O2, LiOH, THF, H2O; successful sequence (d) Pd/C, AcOH, H2O, t-BuOH (e) H2O2, LiOH, THF, H2O, 37% over two steps.

Conclusion

The first total synthesis of the S. pneumoniae serotype 12F capsular polysaccharide repeating unit hexasaccharide 1 was achieved by means of a linear approach. A convergent [3 + 3] total synthesis strategy failed, most likely due to steric crowding around the trisaccharide acceptor. The synthesis of 1 is an illustrative example of the challenges associated with state-of-the-art oligosaccharide assembly including steric, conformational, remote participation groups and solvent effects. It lends further credence to the linear assembly concept in which one monosaccharide unit at a time is incorporated, and which serves as the basis for automated glycan assembly [43]. With the synthetically sourced hexasaccharide repeating unit in hand detailed immunological analysis of S. pneumoniae serotype 12F can be undertaken, and future work will address the expanded inclusion of this antigen in next-generation glycoconjugate vaccines.

Abbreviations

Ac: acetate ester; BAIB: bis(acetoxy)iodobenzene; Bz: benzoyl; CPS: capsular polysaccharide; DMF: N,N-dimethylformamide; EtOAc: ethyl acetate; GlcA: glucouronic acid; HPLC: high-performance liquid chromatography; Lev: levulinoyl; MALDI–TOF MS: matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry; NAP: 2-naphthylmethyl; TBS: tert-butyldimethylsilyl; THF: tetrahydrofuran; TMSOTf: trimethylsilyl trifluoromethanesulfonate.

Supporting Information

Experimental details and full characterization data of all new compounds.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Max Planck Society and the Körber Foundation (Award to P.H.S.) for generous financial support and Dr. Allison Berger for editing the manuscript.

References

- 1.Friedländer C. Fortschr Med. 1883;1:715–733. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pasteur L. Bull Acad Med (Paris, Fr) 1881;10:94–103. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sternberg G M. Nat Board Health Bull. 1881;2:781–783. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Musher D M. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;14:801–809. doi: 10.1093/clinids/14.4.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O'Brien K L, Wolfson L J, Watt J P, Henkle E, Deloria-Knoll M, McCall N, Lee E, Mulholland K, Levine O S, Cherian T. Lancet. 2009;374:893–902. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61204-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henrichsen J. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2759–2762. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.10.2759-2762.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lund E, Henrichsen J. Laboratory Diagnosis, Serology and Epidemiology of Streptococcus pneumoniae. In: Bergan T, Norris J R, editors. Methods in Microbiology. Vol. 12. Academic Press; 1978. pp. 241–262. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reeves R E, Goebel W E. J Biol Chem. 1941;139:511–519. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moxon E R, Kroll J S. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1990;150:65–85. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-74694-9_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Austrian R. Clin Infect Dis. 1981;3(Suppl S1):S1–S17. doi: 10.1093/clinids/3.Supplement_1.S1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Austrian R. Clin Infect Dis. 1989;11(Suppl S3):S598–S602. doi: 10.1093/clinids/11.Supplement_3.S598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Committee on Infectious Diseases Pediatrics. 2010;126:186–190. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Plosker G L. Pediatr Drugs. 2013;15:403–423. doi: 10.1007/s40272-013-0047-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park I H, Pritchard D G, Cartee R, Brandao A, Brandileone M C C, Nahm M H. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:1225–1233. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02199-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heidelberger M, Avery O T. J Exp Med. 1924;40:301–316. doi: 10.1084/jem.40.3.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Calix J J, Nahm M H. J Infect Dis. 2010;202:29–38. doi: 10.1086/653123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robbins J B, Austrian R, Lee C J, Rastogi S C, Schiffman G, Henrichsen J, Makela P H, Broome C V, Facklam R R, Tiesjema R H, et al. J Infect Dis. 1983;148:1136–1159. doi: 10.1093/infdis/148.6.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rodgers G L, Arguedas A, Cohen R, Dagan R. Vaccine. 2009;27:3802–3810. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oberli M A, Tamborrini M, Tsai Y-H, Werz D B, Horlacher T, Adibekian A, Gauss D, Möller H M, Pluschke G, Seeberger P H. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:10239–10241. doi: 10.1021/ja104027w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Werz D B, Seeberger P H. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2005;44:6315–6318. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tamborrini M, Werz D B, Frey J, Pluschke G, Seeberger P H. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2006;45:6581–6582. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson M A, Pinto B M. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:15368–15374. doi: 10.1021/ja020983v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu X H, Sun Y, Frasch C, Concepcion N, Nahm M H. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1999;6:519–524. doi: 10.1128/cdli.6.4.519-524.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Codée J D C, Christina A E, Walvoort M T C, Overkleeft H S, van der Marel G A. Uronic Acids in Oligosaccharide and Glycoconjugate Synthesis. In: Fraser-Reid B, Cristóbal López J, editors. Reactivity Tuning in Oligosaccharide Assembly. Vol. 301. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2011. pp. 253–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van den Bos L J, Codée J D C, Litjens R E J N, Dinkelaar J, Overkleeft H S, van der Marel G A. Eur J Org Chem. 2007:3963–3976. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.200700101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lefeber D J, Kamerling J P, Vliegenthart J F G. Chem – Eur J. 2001;7:4411–4421. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20011015)7:20<4411::AID-CHEM4411>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Allevi P, Paroni R, Ragusa A, Anastasia M. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2004;15:3139–3148. doi: 10.1016/j.tetasy.2004.08.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Jong A-R, Hagen B, van der Ark V, Overkleeft H S, Codée J D C, van der Marel G A. J Org Chem. 2012;77:108–125. doi: 10.1021/jo201586r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Polat T, Wong C-H. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:12795–12800. doi: 10.1021/ja073098r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Z, Xu Y, Yang B, Tiruchinapally G, Sun B, Liu R, Dulaney S, Liu J, Huang X. Chem – Eur J. 2010;16:8365–8375. doi: 10.1002/chem.201000987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu X, Cui L, Lipinski T, Bundle D R. Chem – Eur J. 2010;16:3476–3488. doi: 10.1002/chem.200902460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kramer S, Nolting B, Ott A-J, Vogel C. J Carbohydr Chem. 2000;19:891–921. doi: 10.1080/07328300008544125. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Daragics K, Fügedi P. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009;50:2914–2916. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2009.03.194. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eller S, Collot M, Yin J, Hahm H S, Seeberger P H. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2013;52:5858–5861. doi: 10.1002/anie.201210132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Demchenko A V, Rousson E, Boons G-J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:6523–6526. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(99)01203-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weishaupt M W, Matthies S, Seeberger P H. Chem – Eur J. 2013;19:12497–12503. doi: 10.1002/chem.201204518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.BeMiller J N, Kumari G V. Carbohydr Res. 1972;25:419–428. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6215(00)81653-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walvoort M T C, Volbeda A G, Reintjens N R M, van den Elst H, Plante O J, Overkleeft H S, van der Marel G A, Codée J D C. Org Lett. 2012;14:3776–3779. doi: 10.1021/ol301666n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fraser-Reid B, Cristobal Lopez J, Radhakrishnan K V, Mach M, Schlueter U, Gomez A, Uriel C. Can J Chem. 2002;80:1075–1087. doi: 10.1139/v02-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fraser-Reid B, Cristóbal López J, Gómez A M, Uriel C. Eur J Org Chem. 2004:1387–1395. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.200300689. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walvoort M T C, Lodder G, Overkleeft H S, Codée J D C, van der Marel G A. J Org Chem. 2010;75:7990–8002. doi: 10.1021/jo101779v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shangguan N, Katukojvala S, Greenberg R, Williams L J. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:7754–7755. doi: 10.1021/ja0294919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seeberger P H. Acc Chem Res. 2015;48:1450–1463. doi: 10.1021/ar5004362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Experimental details and full characterization data of all new compounds.