Abstract

Regulation of intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) is vital for eukaryotic organisms. Recently, we identified a Ca2+ channel (TcIP 3R) associated with intracellular Ca2+ stores in Trypanosoma cruzi, the parasitic protist that causes Chagas disease. In this study, we measured [Ca2+]i during the parasite life cycle and determined whether TcIP 3R is involved in the observed variations. Parasites expressing R‐GECO1, a red fluorescent, genetically encoded Ca2+ indicator for optical imaging that fluoresces when bound to Ca2+, were produced. Using these R‐GECO1‐expressing parasites to measure [Ca2+]i, we found that the [Ca2+]i in epimastigotes was significantly higher than that in trypomastigotes and lower than that in amastigotes, and we observed a positive correlation between TcIP 3 R mRNA expression and [Ca2+]i during the parasite life cycle both in vitro and in vivo. We also generated R‐GECO1‐expressing parasites with TcIP 3R expression levels that were approximately 65% of wild‐type (wt) levels (SKO parasites), and [Ca2+]i in the wt and SKO parasites was compared. The [Ca2+]i in SKO parasites was reduced to approximately 50–65% of that in wt parasites. These results show that TcIP 3R is the determinant of [Ca2+]i in T. cruzi. Since Ca2+ signaling is vital for these parasites, TcIP 3R is a promising drug target for Chagas disease.

Keywords: intracellular Ca2+ concentration, IP3 receptor, life cycle, live cell Imaging, Trypanosoma cruzi

Abbreviations

- [Ca2+]i

intracellular Ca2+ concentration

- IP3Rs

inositol 1,4,5‐trisphosphate receptors

- R‐GECO1

red fluorescent, genetically encoded Ca2+ indicator for optical imaging

- SKO

single‐knockout

- TcIP3R

IP3R homolog in T. cruzi

Calcium ion (Ca2+) is the most important and versatile intracellular messenger in eukaryotes 1. Ca2+ signaling regulates various biological process, including secretion, fertilization, cell growth, and cell death 2; thus, the regulation of intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) is vital. In mammals, [Ca2+]i is regulated by several factors, including Ca2+ influx into the cytosol through voltage‐gated Ca2+ channels (VGCCs), receptor‐operated Ca2+ channels (ROCs), and store‐opened Ca2+ channels (SOCs); buffering of Ca2+ with plasma membrane and cytosolic proteins; accumulation of Ca2+ in intracellular Ca2+ stores through the sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+‐ATPase (SERCA); and efflux of Ca2+ from stores through Ca2+ channels, such as inositol 1,4,5‐trisphosphate receptors (IP3Rs), and ryanodine receptors (RyRs) 3.

Trypanosoma cruzi is the parasitic protist that causes Chagas disease in Latin America. At present, only two drugs are available for Chagas disease (benznidazole and nifurtimox), and these often induce severe side effects and are effective for only the acute phase of the disease. Since no practical drug or vaccine for Chagas disease is available, new treatments are greatly needed 4. The life cycle of the parasite comprises two phases, the insect and mammalian phases 5. In the insect vector (the reduviid bug), the epimastigote replicates and transforms into a metacyclic trypomastigote (metacyclogenesis). A nonproliferating metacyclic trypomastigote invades a mammalian host, and is then transformed into an amastigote inside a wide variety of nucleated cells. The intracellular amastigote multiplies by binary fission, and is then transformed back into a trypomastigote, which is released into the circulation after host cell disruption.

[Ca2+]i regulation is vital for T. cruzi, and the molecular mechanisms of [Ca2+]i regulation in the parasite are thought to be quite different from those in mammalian cells 6. In fact, no homologs of the typical Ca2+ transporters—ROCs, SOCs, or Na+/Ca2+ exchangers, have been detected in Trypanosomes. The results of a proteome analysis of T. brucei suggested that a putative VGCC is localized to the flagellum 7. Two homologs of plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPase (PMCA) have also been reported; one is localized on the plasma membrane, and the other is localized to the acidocalcisome of T. brucei 8. In addition, a SERCA has been shown to be localized to the ER of T brucei like mammalian cells 9. However, no RyR homologs have been reported. Recently, we identified an IP3R homolog in T. cruzi (TcIP3R), and showed that it is mainly localized to the ER. When the expression level of TcIP3R is reduced to less than one‐half of that in wild‐type (wt) cells, the parasite cannot grow 10. Therefore, TcIP3R may be a promising drug target 11. We also previously showed that TcIP3R regulates parasite growth, transformation, infectivity, and virulence in mammalian hosts, indicating that TcIP3R is an important regulator of the parasite life cycle 10, 12. In fact, experiments using classical Ca2+ indicators, such as Fura‐2, showed that Ca2+ signaling is important for host cell invasion 10, 13, 14 as well as proliferation and transformation 15.

In this paper, we reported the successful preparation of parasites expressing R‐GECO1 (a red fluorescent, genetically encoded Ca2+ indicator for optical imaging), which is a green fluorescent protein (GFP) variant that fluoresces only upon binding to Ca2+ 16. It has recently been reported that other parasites including Plasmodium falciparum and Toxoplasma gondii that express genetically encoded Ca2+ indicators are useful for investigating Ca2+ signaling in the parasite 17, 18. Importantly, our findings revealed that analysis of T. cruzi expressing R‐GECO1 revealed that the [Ca2+]i in the parasite changes significantly during its life cycle, and that TcIP3R is the determinant of [Ca2+]i in T. cruzi.

Materials and methods

Plasmid construction

The R‐GECO1 gene was amplified by PCR from the pCMV‐R‐GECO1 plasmid vector (Addgene, plasmid 45494) using specific primers (forward: 5′‐CACCATGGTCGACCTTCACGTCGTA‐3′ and reverse: 5′‐CTACTTCGCTGTCATCATTTGTAC‐3′; the CACC sequence required for directional cloning in pENTR/D‐TOPO is underlined) and KOD‐Plus Neo (TOYOBO Co., Ltd, Osaka, Japan). The PCR‐amplified gene was inserted into pENTR/D‐TOPO (Life Technologies, Rockville, MD, USA). The resultant plasmid, pENTR/R‐GECO1, was converted to a pTREX vector 19, 20, which contains a neomycin resistance gene as the selection marker, and was modified by the Gateway Vector Conversion System (pTREX(neoR)‐GW; Life Technologies) using the Gateway recombination system, to generate pTREX (neoR)‐GW/R‐GECO1.

The puromycin resistance gene was amplified by PCR using pBApo‐CMV Pur DNA plasmid vector (Clontech Laboratories, Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) as the template with the specific primers (forward: 5′‐ATGACCGAGTACAAGCCCAC‐3′ and reverse: 5′‐TCAGGCACCGGGCTTGC‐3′). To remove the neomycin resistance gene from pTREX (neoR)‐GW/R‐GECO1, we used PCR with pTREX (neoR)‐GW/R‐GECO1 as the template and the primers (forward: 5′‐GGGGATCGATCCGGAACAA‐3′ and reverse: 5′‐ATTGGCTGCAGGGTCGCT‐3′). These two PCR fragments were ligated with DNA Ligation Kit Ver. 2.1 (Takara Bio Inc., Shiga, Japan), to generate pTREX (purR)‐GW/R‐GECO1.

Cell culture

Epimastigotes of the T. cruzi Tulahuen strain were cultured as previously described 21. The mammalian stages of the parasites were maintained in HeLa cells or 3T3‐Swiss albino cells (Health Science Research Resources Bank, Tokyo, Japan), and trypomastigotes were collected from subcultures of infected 3T3‐Swiss albino cells by centrifugation as previously described 22. Metacyclogenesis was performed as previously described 23. Quantitative real‐time RT‐PCR analysis was performed as previously described 10. 1,2‐Bis(2‐aminophenoxy)ethane‐N,N,N′,N′‐tetraacetic acid (BAPTA), which is a cell‐impermeant Ca2+ chelator and reduces the levels of extracellular Ca2+, and 1,2‐Bis(2‐aminophenoxy)ethane‐N,N,N′,N′‐tetraacetic Acid, tetraacetoxymethyl ester (BAPTA‐AM), which is a cell‐permeant Ca2+ chelator thereby reduces [Ca2+]i, were purchased from Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Inc. (Kumamoto, Japan), and an IP3R inhibitor, 2‐aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2‐APB), was purchased from Sigma‐Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Expression of R‐GECO1 in T. cruzi

A total of 1 × 107 epimastigotes were resuspended in Amaxa Basic® Parasite Nucleofector Kit 2 solution (Lonza, Köln, Germany). The resuspended wt or TcIP3R SKO parasites 10 were mixed with 10 μg of pTREX (neoR)/R‐GECO1 or pTREX (purR)/R‐GECO1, respectively, and then electroporated with an Amaxa Nucleofector Device (Lonza) using program U‐033. Stable wt transformants expressing R‐GECO1 were selected by incubating the cells for 30 days in LIT medium containing 0.5 mg·mL−1 G418, and then clonal derivatives were isolated by limiting dilution. The stable SKO transformants expressing R‐GECO1 were selected by incubating the cells for 30 days in LIT medium containing 0.25 mg·mL−1 G418 and 3 μg·mL−1 puromycin. Amastigotes or trypomastigotes stably expressing R‐GECO1 were transformed from the epimastigotes expressing R‐GECO1 using the methods described above.

Detection of [Ca2+]i by fluorescence microscopy

Fluorescence images of the parasites were acquired using a fluorescent microscope (Axio Imager M2; Carl Zeiss Co. Ltd., Oberkochen, Germany) or a laser confocal microscope (Nikon A1R, Nikon Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). After acquiring fluorescence images in normal culture medium, the maximal fluorescence signal (F max) of R‐GECO1 in individual parasites was determined by treating them with high Ca2+ solution (10 mm) and ionomycin (0.26 mm; Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan), which increase the cytosolic Ca2+ content of parasites so as to saturate R‐GECO1 with Ca2+. To convert fluorescence intensity to Ca2+ concentration, the following formula was used:

where K d is the dissociation constant for R‐GECO1 (482 nm); n is the Hill coefficient of R‐GECO1 (2.0); F is the fluorescence intensity in each parasite; F MAX is the maximal fluorescence intensity of R‐GECO1 in the parasite (see above); and F MIN is the minimal intensity of R‐GECO1 calculated using the ratio change value obtained by Zhao et al. (= 1/16 of F MAX).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with sigma plot ver. 12 software (Systat Software, Inc., San Jose, CA, USA) using one‐way ANOVA or Student's t‐test.

Results and Discussion

The [Ca2+]i changes significantly during the life cycle of T. cruzi

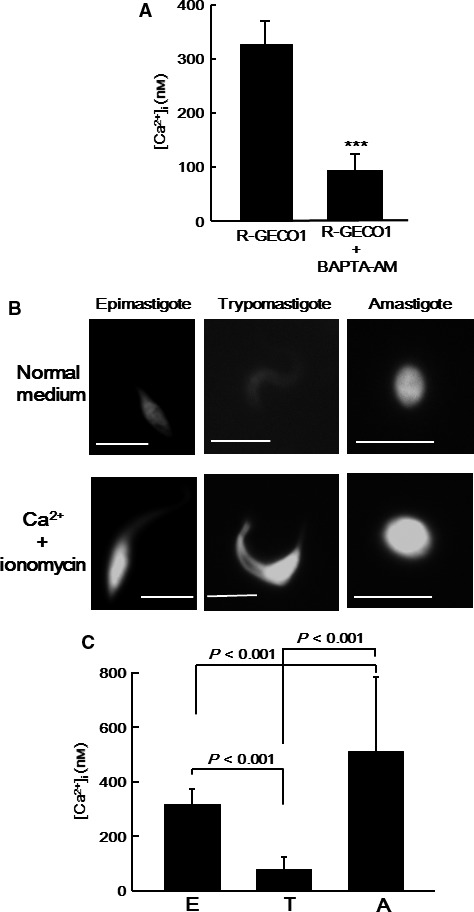

To investigate the changes in the [Ca2+]i in T. cruzi during its life cycle, parasites expressing R‐GECO1 were prepared. The R‐GECO1 gene was cloned in the T. cruzi pTREX expression vector 19, in which R‐GECO1 is expressed under the ribosomal promoter; therefore, R‐GECO1 was constitutively expressed throughout the parasite life cycle. We at first investigated whether the fluorescence signal in the parasites expressing R‐GECO1 was reduced after treatment with a cell‐permeant Ca2+ chelator BAPTA‐AM. After replacement of the parasite medium with PBS, BAPTA‐AM (final concentration 100 μm) was added to the PBS to reduce Ca2+, and [Ca2+]i was measured after 3 min (Fig. 1A). Treatment of the parasites with BAPTA‐AM significantly reduced the parasite [Ca2+]i, indicating that R‐GECO1 works as a Ca2+ indicator in the parasites. We also found that the parasites were killed by the treatment.

Figure 1.

Changes in T. cruzi [Ca2+]i during its life cycle. (A) The fluorescence intensity of epimastigotes expressing R‐GECO1 was measured after treatment with 100 μm BAPTA‐AM for 3 min. The [Ca2+]i were calculated from the fluorescence intensity and compared to that in untreated epimastigotes. The fluorescence intensity of 20 parasites for each condition was measured. Statistical analysis between the two groups was performed using Student's t‐test. ***P < 0.001. (B) Typical images of a clonal derivative of T. cruzi expressing R‐GECO1 in normal culture medium (top) and in high Ca2+ medium with ionomycin (bottom), including an epimastigote, trypomastigote, and amastigote, are shown. Bar, 5 μm. (C) The [Ca2+]i in epimastigotes (E), trypomastigotes (T), and amastigotes (A), as measured by fluorescence intensity, was compared. The fluorescence intensity of 20 parasites was measured for each stage. Statistical analysis between the groups was performed using one‐way ANOVA and Tukey's Test.

To exclude variations in signal intensity among the parasite clones, a clonal derivative was isolated and used for the experiments. Figure 1B shows the R‐GECO1 signal in the epimastigote, trypomastigote, and amastigote. Although the signal was detected throughout the cytoplasm of the parasites at all stages, the signal intensity was quite different among the different life cycle stages, and the maximal fluorescence intensities of R‐GECO1 obtained in the presence of 260 μm ionomycin and 10 mm Ca2+ were similar. The [Ca2+]i was calculated from the R‐GECO1 signal intensity and compared among the three stages, as described in the Methods section (Fig. 1C). The [Ca2+]i was clearly higher in amastigotes (579 ± 204 nm) and epimastigotes (327 ± 44 nm) than in trypomastigotes (85 ± 39 nm). These results indicated that the [Ca2+]i changes significantly during the progression of the parasite life cycle. Ca2+ oscillation was not detected at any stage.

Live cell imaging revealed changes in the [Ca2+]i of T. cruzi parasitizing host cells

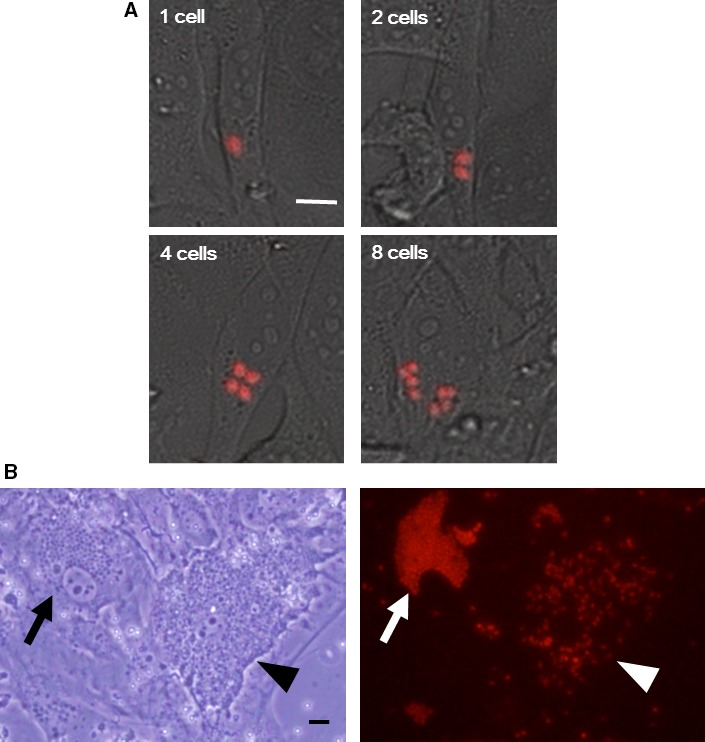

We further investigated the changes in the [Ca2+]i of parasites during intracellular growth. 3T3‐Swiss cells were infected with R‐GECO1‐expressing trypomastigotes, and then the growth of one parasite was monitored under a fluorescent microscope (Fig. 2A). We successfully monitored them until the parasite divided three times within a host cell. The results showed that the [Ca2+]i in amastigotes did not change significantly after division.

Figure 2.

Changes in T. cruzi [Ca2+]i within host cells. (A) 3T3‐Swiss albino cells were infected with R‐GECO1‐expressing trypomastigotes (red), and imaged 84 h after infection. The movement of an amastigote was recorded using real‐time confocal microscopy with 40× dry objective lens (Nikon AIR). The time interval of the serial images was 15 min. The amastigotes (one cell) that divided once (two cells), twice (four cells), and three times (eight cells) are shown. Bar, 5 μm. (B) A bright‐field image of cells that are heavily infected with R‐GECO1‐expressing amastigotes (arrow) and trypomastigotes (arrowhead) is shown (left). A representative microscopic image was obtained with an inverted microscope (IX72; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). A video of the same field is available as Movie S1. Note that the trypomastigotes in the host cell move intensely. A fluorescent image of the same field is also shown (right). Bar, 10 μm.

Amastigotes divide several times within host cells, transform into trypomastigotes, and then lyse the host cells. We investigated whether the [Ca2+]i in trypomastigotes parasitizing host cells was decreased similar to that observed in tissue culture‐derived trypomastigotes (Fig. 2B, Movie S1). The results showed that the [Ca2+]i in trypomastigotes within host cells (Fig. 2B, arrowhead in the right panel) was significantly lower than that in amastigotes (Fig. 2B, arrow in the right panel).

These results indicate that amastigotes are able to maintain [Ca2+]i even in environments where the Ca2+ concentration is very low, such as the cytosol of host cells, and that the [Ca2+]i in the trypomastigote when inside host cells is significantly lower than that in the amastigote [Ca2+]i.

TcIP3R is the determinant of [Ca2+]i in T. cruzi

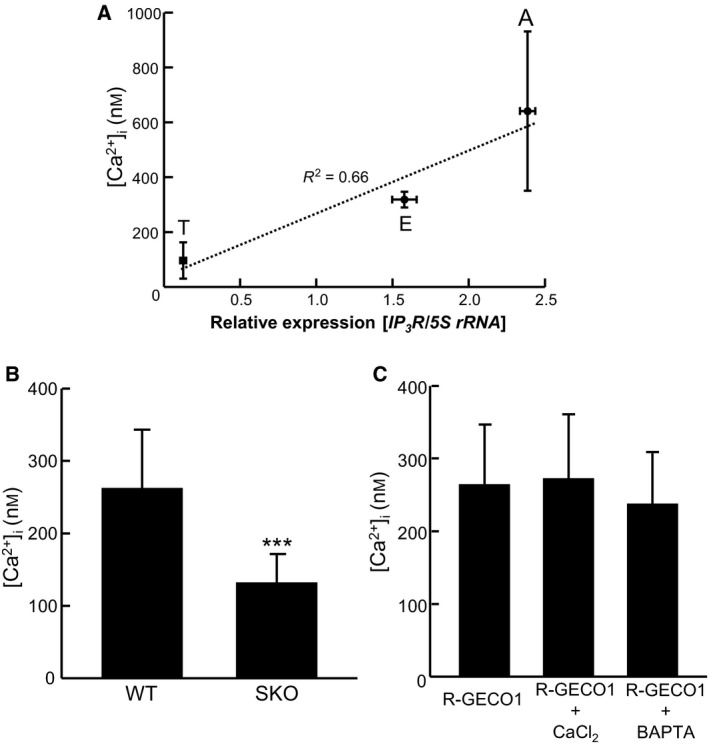

Previously, we reported that TcIP 3 R mRNA expression varied significantly among the parasite life cycle stages 10. Here, we investigated a possible correlation between TcIP 3 R mRNA expression and the [Ca2+]i of the parasite (Fig. 3A). There was a positive correlation between the parasite [Ca2+]i at each life stage and the TcIP 3 R mRNA expression level (R 2 = 0.66). These results suggest that TcIP3R is important for the regulation of [Ca2+]i in T. cruzi.

Figure 3.

Effect of Ca2+ chelators or reduced TcIP 3R expression on T. cruzi [Ca2+]i. (A) Correlation between TcIP 3 R mRNA expression level and [Ca2+]i in T. cruzi throughout the parasite life cycle. [Ca2+]i shows a linear relationship with TcIP 3 R mRNA expression (R 2 = 0.66). To measure [Ca2+]i, the R‐GECO1 fluorescence intensity of 20 parasites was measured. To measure TcIP 3 R mRNA expression, quantitative real‐time RT‐PCR analysis of relative transcript levels was performed, and the data shown are the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. (B) [Ca2+]i was compared between R‐GECO1‐expressing wt and SKO epimastigotes. The fluorescence intensity of 20 parasites was measured. Statistical analysis between the groups was performed using Student's t‐test. ***P < 0.001. (C) R‐GECO1‐expressing epimastigotes were treated with 10 mm CaCl2 or 10 mm BAPTA for 2 h; fluorescence was measured, and [Ca2+]i was calculated and compared to that in untreated parasites. The fluorescence intensity of 20 parasites was measured.

To investigate whether TcIP3R is involved in the regulation of [Ca2+]i in T. cruzi, the level of TcIP 3 R was reduced in parasites expressing R‐GECO1, and the [Ca2+]i in wt and mutant parasites was measured (Fig. 3B). We previously found three TcIP 3 R genes in the genome of the T. cruzi Tulahuen strain, and we prepared single‐knockout (SKO) parasites, in which one of the TcIP 3 R genes was disrupted by homologous recombination 10. We observed the specific disruption of only one TcIP 3 R gene by Southern blot analysis and an approximately 35% reduction in TcIP3R expression levels in the SKO parasites, and these parasites show various phenotypes, such as inhibition of epimastigote growth 10. Since the knockout cassette used to prepare the SKO parasites contained a neomycin resistance gene, the transformants were selected with G418. Then, the R‐GECO1 gene was cloned into an expression plasmid vector for T. cruzi containing a puromycin resistance gene (pTREX(purR)), and then this plasmid was transfected into the SKO parasites. SKO parasites expressing R‐GECO1 were selected in culture medium containing G418 and puromycin. For the control, wt Tulahuen strain parasites were transfected with pTREX(purR)/R‐GECO1 and selected in culture medium containing puromycin. Since the expression level of R‐GECO1 among the parasite clones might vary, the fluorescence intensity in the parasites was randomly measured without cloning. The fluorescence intensity in the SKO parasites was significantly lower than that in the wt parasites. Importantly, the TcIP3R expression level in the SKO parasites was reduced to approximately 65% of wt levels 10, and the R‐GECO1 signal in SKO parasites was reduced to approximately 50% of wt levels.

Next, we investigated whether Ca2+ influx from the extracellular fluid or efflux to the extracellular fluid is important for maintenance of [Ca2+]i (Fig. 3C). Excessive amounts of CaCl2 or BAPTA, a noncell‐permeable Ca2+ chelator, was added to the cultivation medium of epimastigotes expressing R‐GECO1, and the [Ca2+]i in treated parasites was compared to that in untreated parasites after 2 h. No increase was detected in parasites treated with CaCl2 compared to that in untreated parasites. When the Ca2+ in the culture medium was chelated by the addition of BAPTA, we speculated that [Ca2+]i might be reduced by PMCA function. However, the [Ca2+]i in parasites treated with BAPTA was not reduced when compared with that in untreated parasites. These results indicate that T. cruzi do not constitutively import or export Ca2+. Therefore, Ca2+ released from intracellular Ca2+ store(s) into the cytosol by TcIP3R should be effectively returned to the store(s) by SERCA 24, 25.

In animal cells, [Ca2+]i are kept at low concentrations (~ 100 nm) in the absence of extracellular stimuli 26. Phosphoinositide phospholipase C (PI‐PLC) is activated in response to signals from cell surface receptors, and it catalyzes the hydrolysis of phosphatidylinositol 4,5‐bisphosphate (PIP2) to generate IP3, which activates IP3R and transiently increases [Ca2+]i 27. Our present data indicate that [Ca2+]i in epimastigotes and amastigotes is constitutively high. Recently, it has been reported that Trypanosoma brucei PI‐PLC may be constitutively activated 28. Furthermore, the molecular properties of T. cruzi PI‐PLC have been reported to be similar to that of T. brucei PI‐PLC 29 (e.g., plasma membrane localization). Together, these findings suggest that constitutive activation of T. cruzi PI‐PLC might maintain high [Ca2+]i through constitutive TcIP3R activation.

According to the cell boundary theorem, [Ca2+]i is determined by the balance between Ca2+ influx and efflux, and Ca2+ release via IP3R does not result in higher [Ca2+]i 30, 31. In mammalian cells, Ca2+ influx increases through the SOC mechanism activated by Ca2+ release from the ER, thereby resulting in an increase of [Ca2+]i 25. Furthermore, it might be possible that [Ca2+]i in T. cruzi is not always increased through TcIP3R directly but the parasites have some unknown mechanism(s) to increase Ca2+ influx. Interestingly, since amastigotes parasitize the host cell cytoplasm, where the concentration of Ca2+ is much lower than the [Ca2+]i in amastigotes, the parasites may not receive Ca2+ from outside through a SOC‐like mechanism. However, how amastigotes maintain high [Ca2+]i within the host cells remains unknown at present.

In conclusion, our present study revealed that basal [Ca2+]i levels in T. cruzi are determined by the level of TcIP3R expression. Since Ca2+ signaling is essential for the parasite and the primary structure of TcIP3R shares low similarity with that of mammalian IP3Rs, TcIP3R, the key Ca2+ signaling molecule, is a promising drug target for Chagas disease.

Author contributions

MH, MD, NK, KM, and NT designed the study. MH, MD, NK, KF, and HM did the experiments. MH, MD, NK, and TN wrote the manuscript. MH, MD, NK, KF, HM, YO, TS, TM, KM, and TN interpreted the data. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Supporting information

Movie S1. Changes in T. cruzi [Ca2+]i within host cells. 3T3‐Swiss albino cells were infected with R‐GECO1‐expressing trypomastigotes. A bright‐field movie of cells that are heavily infected with R‐GECO1‐expressing amastigotes and trypomastigotes is shown (A). A representative microscopic movie was obtained with an inverted microscope (IX72; Olympus). Note that the trypomastigotes in the host cell move intensely. A fluorescent image of the same field is also shown (B).

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Mariano J. Levin (Instituto de Investigaciones en Ingeniería Genética y Biología Molecular [INGEBI‐CONICET]) for providing the pTREX vector. We thank Ms. Tsukakoshi for technical assistance. This work was supported by two grants from JSPS KAKENHI (15K08452 [to MH] and 24390102 [to TN]), by the Pharmacological Research Foundation, Tokyo (to MH).

References

- 1. Petersen OH, Michalak M and Verkhratsky A (2005) Calcium signalling: past, present and future. Cell Calcium 38, 161–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bootman MD, Lipp P and Berridge MJ (2001) The organisation and functions of local Ca(2+) signals. J Cell Sci 114, 2213–2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Weber JT (2012) Altered calcium signaling following traumatic brain injury. Front Pharmacol 3, 60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chatelain E (2014) Chagas disease drug discovery: toward a new era. J Biomol Screen 20, 22–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brener Z (1973) Biology of Trypanosoma cruzi . Annu Rev Microbiol 27, 347–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Docampo R, Moreno SN and Plattner H (2014) Intracellular calcium channels in protozoa. Eur J Pharmacol 739, 4–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Oberholzer M, Langousis G, Nguyen HT, Saada EA, Shimogawa MM, Jonsson ZO, Nguyen SM, Wohlschlegel JA and Hill KL (2011) Independent analysis of the flagellum surface and matrix proteomes provides insight into flagellum signaling in mammalian‐infectious Trypanosoma brucei . Mol Cell Proteomics 10, M111.010538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Luo S, Rohloff P, Cox J, Uyemura SA and Docampo R (2004) Trypanosoma brucei plasma membrane‐type Ca(2+)‐ATPase 1 (TbPMC1) and 2 (TbPMC2) genes encode functional Ca(2+)‐ATPases localized to the acidocalcisomes and plasma membrane, and essential for Ca(2+) homeostasis and growth. J Biol Chem 279, 14427–14439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Docampo R, Moreno SN and Vercesi AE (1993) Effect of thapsigargin on calcium homeostasis in Trypanosoma cruzi trypomastigotes and epimastigotes. Mol Biochem Parasitol 59, 305–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hashimoto M, Enomoto M, Morales J, Kurebayashi N, Sakurai T, Hashimoto T, Nara T and Mikoshiba K (2013) Inositol 1,4,5‐trisphosphate receptor regulates replication, differentiation, infectivity and virulence of the parasitic protist Trypanosoma cruzi . Mol Microbiol 87, 1133–1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hashimoto M, Nara T, Hirawake H, Morales J, Enomoto M and Mikoshiba K (2014) Antisense oligonucleotides targeting parasite inositol 1,4,5‐trisphosphate receptor inhibits mammalian host cell invasion by Trypanosoma cruzi . Sci Rep 4, 4231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hashimoto M, Morales J, Uemura H, Mikoshiba K and Nara T (2015) A novel method for inducing amastigote‐to‐trypomastigote transformation in vitro in Trypanosoma cruzi reveals the importance of inositol 1,4,5‐trisphosphate receptor. PLoS One 10, e0135726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Moreno SN, Silva J, Vercesi AE and Docampo R (1994) Cytosolic‐free calcium elevation in Trypanosoma cruzi is required for cell invasion. J Exp Med 180, 1535–1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yakubu MA, Majumder S and Kierszenbaum F (1994) Changes in Trypanosoma cruzi infectivity by treatments that affect calcium ion levels. Mol Biochem Parasitol 66, 119–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lammel EM, Barbieri MA, Wilkowsky SE, Bertini F and Isola EL (1996) Trypanosoma cruzi: involvement of intracellular calcium in multiplication and differentiation. Exp Parasitol 83, 240–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhao Y, Araki S, Wu J, Teramoto T, Chang YF, Nakano M, Abdelfattah AS, Fujiwara M, Ishihara T, Nagai T et al (2011) An expanded palette of genetically encoded Ca2+ indicators. Science 333, 1888–1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Borges‐Pereira L, Budu A, McKnight CA, Moore CA, Vella SA, Hortua Triana MA, Liu J, Garcia CR, Pace DA and Moreno SN (2015) Calcium signaling throughout the Toxoplasma gondii lytic cycle: a study using genetically encoded calcium indicators. J Biol Chem 290, 26914–26926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Borges‐Pereira L, Campos BR and Garcia CR (2014) The GCaMP3 – A GFP‐based calcium sensor for imaging calcium dynamics in the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum . MethodsX 1, 151–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vazquez MP and Levin MJ (1999) Functional analysis of the intergenic regions of TcP2beta gene loci allowed the construction of an improved Trypanosoma cruzi expression vector. Gene 239, 217–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lorenzi HA, Vazquez MP and Levin MJ (2003) Integration of expression vectors into the ribosomal locus of Trypanosoma cruzi . Gene 310, 91–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Iizumi K, Mikami Y, Hashimoto M, Nara T, Hara Y and Aoki T (2006) Molecular cloning and characterization of ouabain‐insensitive Na(+)‐ATPase in the parasitic protist, Trypanosoma cruzi . Biochim Biophys Acta 1758, 738–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nakajima‐Shimada J, Hirota Y and Aoki T (1996) Inhibition of Trypanosoma cruzi growth in mammalian cells by purine and pyrimidine analogs. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 40, 2455–2458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gluenz E, Taylor MC and Kelly JM (2007) The Trypanosoma cruzi metacyclic‐specific protein Met‐III associates with the nucleolus and contains independent amino and carboxyl terminal targeting elements. Int J Parasitol 37, 617–625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Parekh AB and Putney JW Jr (2005) Store‐operated calcium channels. Physiol Rev 85, 757–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Smyth JT, Dehaven WI, Jones BF, Mercer JC, Trebak M, Vazquez G and Putney JW Jr (2006) Emerging perspectives in store‐operated Ca2+ entry: roles of Orai, Stim and TRP. Biochim Biophys Acta 1763, 1147–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Syntichaki P and Tavernarakis N (2003) The biochemistry of neuronal necrosis: rogue biology? Nat Rev Neurosci 4, 672–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Berridge MJ (1993) Inositol trisphosphate and calcium signalling. Nature 361, 315–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. King‐Keller S, Moore CA, Docampo R and Moreno SN (2015) Ca2+ regulation of Trypanosoma brucei phosphoinositide phospholipase C. Eukaryot Cell 14, 486–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. de Paulo Martins V, Okura M, Maric D, Engman DM, Vieira M, Docampo R and Moreno SN (2010) Acylation‐dependent export of Trypanosoma cruzi phosphoinositide‐specific phospholipase C to the outer surface of amastigotes. J Biol Chem 285, 30906–30917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ríos E (2010) The cell boundary theorem: a simple law of the control of cytosolic calcium concentration. J Physiol Sci 60, 81–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Friel DD and Tsien RW (1992) A caffeine‐ and ryanodine‐sensitive Ca2+ store in bullfrog sympathetic neurones modulates effects of Ca2+ entry on [Ca2+]i . J Physiol 450, 217–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Movie S1. Changes in T. cruzi [Ca2+]i within host cells. 3T3‐Swiss albino cells were infected with R‐GECO1‐expressing trypomastigotes. A bright‐field movie of cells that are heavily infected with R‐GECO1‐expressing amastigotes and trypomastigotes is shown (A). A representative microscopic movie was obtained with an inverted microscope (IX72; Olympus). Note that the trypomastigotes in the host cell move intensely. A fluorescent image of the same field is also shown (B).