Abstract

The benefits of Person- and Family-Centred Care (PFCC) are well documented, and many healthcare organizations have expressed their commitment to take this approach. Yet, it can be a difficult endeavour, with common barriers identified at the point-of-care, organizational and system levels. We implemented a PFCC education program with healthcare leaders, providers, and support staff working in home, community, and long-term care organizations across Canada. Focus groups were then conducted with almost 200 workshop participants and 20 long-term care home residents and family members. Five key opportunities for healthcare leaders to better support the provision of PFCC were revealed. In this article, specific recommendations from focus group participants for addressing each of these five opportunities are provided. These findings can assist healthcare leaders to proactively ensure the supports and processes are in place to enable staff to provide care in a more person- and family-centred way.

Introduction

The benefits of Person- and Family-Centred Care (PFCC) are well documented,1–7 and many healthcare organizations have expressed their commitment to this approach. The need to be more person-centred is propelled by the focus on PFCC in Accreditation Standards,8,9 which raise the bar for PFCC from direct care to governance levels.10 Yet this can be hard, and research has identified barriers to implementing PFCC, including discrepancies between clients’ and care providers’ goals for care,11 providers’ difficulties transitioning to a partnership approach,12–14 time constraints,13,15 and misunderstandings about what PFCC means.13

Healthcare providers who view care recipients as “dependent,” “helpless,” or gradually losing their “personhood” (eg, in the case of dementia) are less likely to see the need for developing a caring relationship, instead delivering care that is more reflective of a task-oriented approach.16,17

Previous research shows that PFCC should be a shared responsibility between healthcare providers, organizations, and the broader healthcare system.15,18–21 Yet often PFCC strategies are focused primarily at the point of care, with limited guidance for how leaders should support PFCC. What should leaders do?

Methods

To answer this question, this article reports on one component of a broader research project. The aim of the broader study was to determine whether specially-designed educational workshops give participants in different care settings appropriate information in an appropriate way to provide PFCC for their residents (note 1), improve residents’ care experience, and create healthier work environments.

In previous work, we had conducted a literature review of PFCC approaches in home and community care settings18 and a pilot education program with 2,500 Unregulated Care Providers (UCPs), followed by consultations with care providers and recipients. For this study, we developed a broader, revised PFCC education program and delivered it to over 1,500 direct care providers (eg, UCPs, nurses, rehabilitation professionals), support staff (eg, housekeeping, dietary), and management in seven sites across Canada, spanning home care, assisted living, and long-term care.

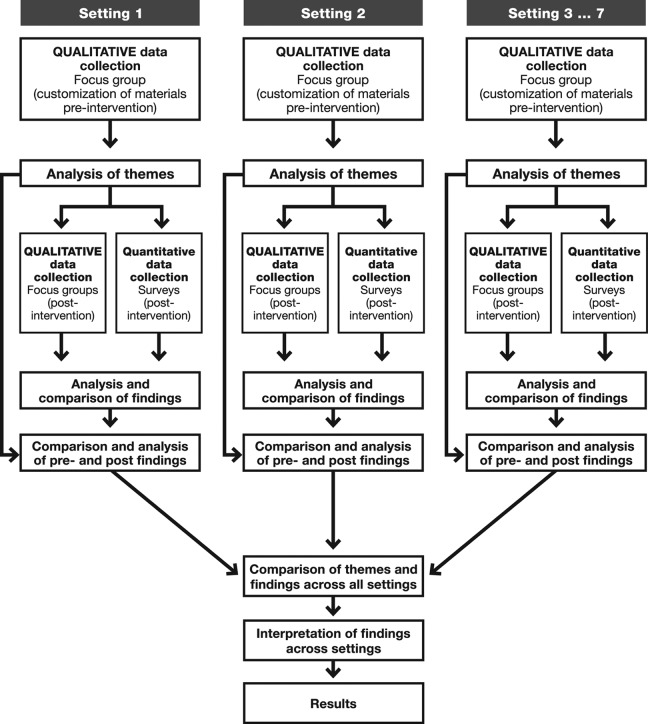

The study took a concurrent transformative approach to multilevel mixed-methods research, with an action research theoretical perspective (Figure 1).22,23 A variety of data within each setting were analyzed iteratively and then compared across sites. Research participants were embedded throughout the planning stages and analysis, with a view to transform the settings in which they worked to be more person- and family-centred.

Figure 1.

Methods convergence table

This article reports only the findings from the focus groups conducted with 192 staff who volunteered from all settings after the PFCC education and 20 residents and family members who volunteered at two pilot sites. In particular, it reports on the themes identified using inductive thematic analysis that centred on the role leaders could play in nurturing PFCC in their organizations.

Results and discussion

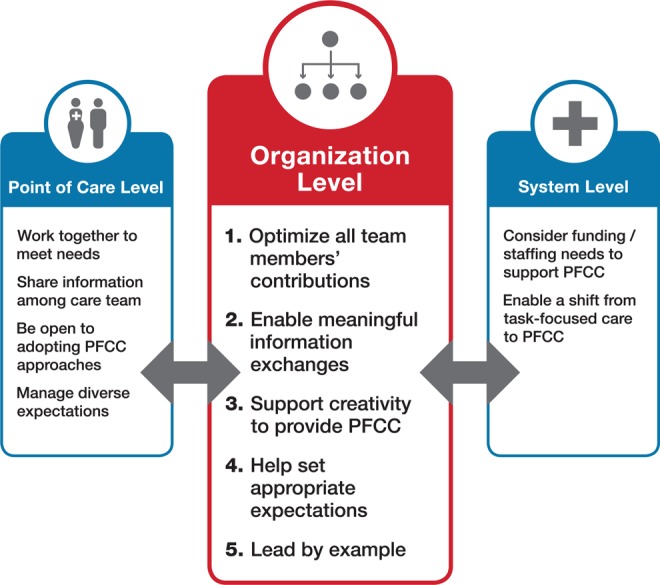

Education workshop participants identified challenges and opportunities to practise PFCC not only at the individual and system levels but also at the organizational level (Figure 2). Our analysis identified five themes that indicate opportunities for healthcare leaders to support PFCC, along with participants’ ideas for leaders’ actions.

Figure 2.

Opportunities to support the practice of Person- and Family-Centred Care (PFCC).

Theme 1: Optimize all team members’ contributions

Workshop participants commented that they did not feel that collaborative team effort was encouraged by their leaders but felt that collaboration is essential to achieve PFCC.

What we heard:

Nursing is the one that has the most responsibility for the residents but lots of the other staff have very meaningful interactions with them on a daily basis, and they feel that those interactions and their opinions are not valued … (Manager—long-term care)

Our management said, “Oh no, you guys aren’t allowed to help (in another unit) … except for with that one lift” … So, where is the team in that?” (UCP—long-term care)

I’ve been told that before, “That’s not your job. Don’t put the sneakers on the residents.” (Housekeeper—long-term care)

I like to feed (my wife). I used to do it. I miss it … They (saw) me feeding her and now I can’t do it. They changed the policy … because she’s a risk of choking. But I already know about her. I know her choking. I know her swallowing. (I) know what she can and cannot have. (Family member—long-term care)

Healthcare organizations tend to be hierarchical, with professionals having a privileged place. However, participants believe that recognizing and promoting the important role that everyone has, including family members, UCPs, and support staff, is vital to PFCC. Encouraging collaborative care and providing interprofessional education can promote respect for the skills and knowledge that each brings to the team.24–27 In addition, role descriptions could be rewritten to highlight team work and mutual assistance.

Theme 2: Enable meaningful information exchanges

A related theme from the focus groups was the need to share information about residents, especially among support staff, UCPs, and casual employees, so they can all provide PFCC.

What we heard:

It would be nice having a heads-up before you go in … especially a new resident’s room, (to know) what to expect. We don’t get that communication. (Maintenance worker—long-term care)

Our support services staff, especially our housekeepers, are always in the room. They’re part of the team. They know an enormous amount of details about residents (and) the resident’s care. They feed (UCPs) and nurses share information, because they’re in there talking to the residents. They see things. (Workshop facilitator—long-term care)

All the frontline staff (do “Comfort Care Rounding”). So you’re “rounding” on your residents all day. So, you go in and you say, “Hi, Mrs. Smith. How are you doing? Are you in any pain today? Are you comfortable? Do you need to use the washroom while I’m here? Do you have everything you need?” …Then letting them know that you’ll be back in an hour and you give them a time… (Then ask), “Is there anything else I can do for you before I leave?” (Workshop facilitator—long-term care)

We heard that staff also do not always share with each other how they provide individualized care, and there are barriers to sharing with family caregivers. Electronic charting may help but not if all providers and caregivers do not have access to the chart, as is usual.

Participants provided suggestions on how leaders can improve information sharing, highlighting the importance of listening to staff to learn who needs to know what and in what format. For example, a one-page “All about me” form, developed from resident preferences, could be used as a conversation starter,28 and regular “rounding” with residents could be encouraged. Another example was allowing a wider circle of staff, including support staff and casual workers, to attend case conferences and team meetings to share information and foster an interprofessional team approach.25 These opportunities for interdisciplinary sharing of strategies and successes can promote peer-to-peer learning in PFCC.27

Theme 3: Support creativity to provide PFCC

Focus group participants identified that rigid policies and rules—which may have defensible intended goals—may actually prevent meeting individual resident needs and preferences. Allowing creativity to respond to individual preferences and needs, however, enables PFCC.

What we heard:

(A resident) would love to just get outside and get some fresh air, but she has no family, so in order for her to get outside, we have to take them. We don’t have the time to take them. So it’s like they’re in these four walls all day. (UCP—long-term care)

… One of the nursing staff said, “… On our floor, we often have residents who don’t have anything. And if I’m out at the store and I see a small pair of shoes and I know Mrs. Jones needs a pair of shoes, I’ll go pick them up … I don’t charge her, I just give them to her.” … So the whole group started to talk … and they all decided what they would do. They thought that was really important to still be able to support the residents in their neighbourhood, but that in order to keep that perception (of favouritism) from happening … they would take it to Social Work, and Social Work could arrange for them to get the item that they needed without any attachment to a staff member on the floor. Because they said, “We get joy out of being able to give … we still want to be able to assist them whenever we can.” (Manager—long-term care)

… They’ve got to remember that it only takes thirty seconds, as you’re putting on socks, just (to ask), “How is your day? How is it going? What’s happening?” Sometimes you’re just so focused on what you’re doing, you forget to … ask those little questions. And, that’s important to them and it makes a big deal … Instead of just, “Time for your pills, let’s go.” (Manager—assisted living)

Leaders need to identify policies and system regulations that are not aligned with a PFCC philosophy and work with policy-makers, staff, residents, and families to consider how to balance potential risks with resident needs and preferences. This might involve considering different ways of providing care, managing risks rather than imposing rules and policies to avoid them, and accepting situations that evolve as staff develop more meaningful relationships with residents and families.

For example, requirements to have all residents at breakfast at a certain time may appear to be efficient, but providing a more flexible approach that encourages residents to choose their own breakfast items from a buffet on their own schedule might be an alternative, at least for some residents. Leaders should support and celebrate care providers who show creativity in meeting resident and family needs and do “little extras.” It is also important to help staff understand how to provide PFCC within limited time constraints. This may be achieved by sharing successes and providing opportunities to try different approaches. Creativity may also come from complementary quality improvement methodologies, such as Kaizen, Lean, or Six Sigma.29,30

Theme 4: Help set appropriate expectations

Person- and family-centred care is not, of course, care that provides whatever residents want when they want it. It is providing care that is consistent with the capacity of individual providers and their organizations and consonant with residents’ preferences and needs. Care providers sometimes feel they cannot provide what residents and family members expect and find it difficult to help them understand what is actually feasible.

What we heard:

(Residents and families) should also be aware that this is what we can do and this is what we can’t do … because we’ve had that discussion. But we can empathize with him of what that must feel like to be without, and then move forward in our care with them.” (Manager—long-term care)

(Residents and families are) looking at it as a fee for service. I’m paying you, you give me what I want. (Manager—long-term care)

Sometimes the client’s family wants you to do more than is actually your job. So (we need) a good way to tell them, “No, I’m not doing that.” (UCP—home care)

I think there should be education initiatives … The patient is saying, “Oh the hospital said you’ll come to my home every day.” … There’s such a disconnect between everybody that nobody knows what’s happening… The physicians should know what service is provided in home, and what they can and cannot do and they don’t. The hospitals don’t know either. (Nurse—home care)

Perhaps the most challenging aspect of PFCC for leaders is finding the balance between meeting residents’ preferences and needs while working within constraints, many of which are externally imposed, such as funding and available skills. While optimizing the capacity of an organization, leaders need to also be setting reasonable expectations for everyone. We heard that during the admission process, attempts could be made to clarify residents’ expectations. An informal “expectations audit,” for example, could provide an opportunity to identify alignment or divergence with available services to reduce future disappointments and frustrations. It could also help to customize the care plan to meet individual needs31 in creative ways (Theme 3). When a resident’s expectations are established outside an organization (eg, hospital staff telling someone what to expect in a long-term care home), leaders should arrange meetings with care providers in those other settings to help them better understand how care is funded, provided, and sometimes constrained, so that they can help set reasonable expectations.

Theme 5: Lead by example

Participants mentioned that they sometimes fear getting in trouble if they share concerns and challenges with their supervisors, indicating that some leaders may not be taking a person-centred approach with staff. Several UCPs felt their knowledge about residents was not valued or respected by their supervisors; others commented that some managers did not lead by example. However, the way care providers are treated can influence how they care for residents.32,33

What we heard:

Most of the time our voice doesn’t matter; what we see, they don’t care … When you know the person, you can say something and (the supervisors) come in, “Why don’t you try this?” When you have tried a million things already and you know what this person wants. (Care provider—long-term care)

There was a resident … management bent over backwards for this resident … meals galore … brought things in, took them out to dinner, had birthday parties … But why are we not allowed? (UCP—long-term care)

We need to model (PFCC) from the top down, and so we have to demonstrate how even though we’re not providing direct care, in our day to day operations … we have (PFCC) as our guide to making decisions …If we’re not modeling it, then how are our staff going to model it? (Manager-long-term care)

Let’s say two employees disagree about something that pertains to the resident. I always ask this question …, “What is in the resident’s best interest? How is (PFCC) … looking at this … ?” That’s kind of the game changer … It really makes people reflect even on their own position in an argument or in a disagreement. (Manager—long-term care)

Think about how you can support your staff in that coaching environment and, if someone’s making their own decisions, setting goals and they’re excited to share that with you and see their progress, that’s huge! This person’s gone from being miserable day to day and not performing well to all of a sudden being assertive and coming to you with good questions … Honestly, it’s like working with a different person. (Manager—home care)

Recommendations

Research has demonstrated the importance of leadership support and direction15,18–21 to embed PFCC principles throughout organizations.10 Participants felt that leaders should model PFCC behaviours with their staff, as they expect staff to do with residents. This includes taking a coaching, collaborative approach with staff to support personal and professional growth and acknowledging their expertise. The PFCC principles should be used to drive decision-making, which might involve, for example, creating a tool/decision-aid to guide team huddle discussions. Care providers want a safe place to share concerns and suggestions without fear of retribution and for leaders to follow up with them when ideas for improvements are made.

Conclusions

Shifting the culture of healthcare organizations to be more person- and family-centred is not an easy undertaking, and it can be daunting for healthcare leaders to determine how best to put PFCC theory into practice. This research provided a unique perspective by speaking to staff and leaders of organizations that have undertaken PFCC initiatives to learn about their challenges and potential solutions. The five themes identified from these rich data provide an evidence base to inform leaders’ approaches. This can help them anticipate the supports and processes needed to champion PFCC, including optimizing all staff contributions, encouraging meaningful information exchange, embracing staff creativity, setting reasonable expectations, and leading by example. The recommendations provide a means and approach to address many of the challenges that employees face when trying to be more person- and family-centred. However, it is essential to provide opportunities and safe spaces for sharing specific concerns about practicing PFCC and collaboratively generate solutions. This may require changing the rules, influencing system-level policy, and new definitions of healthcare teams and how they work together.

Acknowledgments

The authors are deeply grateful to Mary Schulz from the Alzheimer Society of Canada for her continued commitment, support, and guidance throughout this project. The authors would also like to acknowledge the time and efforts of the employees, management, residents, and family members who engaged in this initiative and allowed us to learn from their experiences.

Note

“Resident” was used most frequently by participants in this study; however, it could be used interchangeably with “patient” in primary or acute care settings or “client” in home care settings.

Footnotes

Authors’ note: This research has been made possible through a financial contribution from Health Canada’s Healthcare Policy Contribution Program. The views expressed herein are the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of Health Canada.

References

- 1. McMillan SS, Kendall E, Sav A, et al. Patient-centered approaches to healthcare: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Med Care Res Rev. 2013;70(6):567–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Luxford K, Piper D, Dunbar N, Poole N. Patient-Centred Care: Improving Quality and Safety by Focusing Care on Patients and Consumers. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare (ACSQHC); 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barbosa A, Sousa L, Nolan M, Figueiredo D. Effects of person-centered care approaches to dementia care on staff: a systematic review. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2015;30(8):713–722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. National Ageing Research Institute. What is Person-Centred Healthcare? A Literature Review. Melbourne, Australia: Victorian Government Department of Human Services; 2006. Available at: https://www2.health.vic.gov.au/getfile//?sc_itemid=%7bCC68AD22-6F31-42BE-87FA-287ACB0335FF%7d. Accessed January 12, 2016. Updated November 29, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rave N, Geyer M, Reeder B, et al. Radical systems change. Innovative strategies to improve patient satisfaction. J Ambul Care Manage. 2003;26(2):159–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Scottish Health Council. A Scottish Health Council Report on Improving Quality Through Participation. A Literature Review of the Benefits of Participation in the Context of NHS Scotland’s Healthcare Quality Strategy. Health Improvement Scotland; 2011. Available at: http://www.scottishhealthcouncil.org/publications/research/idoc.ashx?docid=379f923e-1c4b-4e48-b4ba-9e0652aeea18&version=-1. Accessed January 12, 2016. Updated November 29, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. Putting Family Centered Care Philosophy into Practice. Toronto, Canada: Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH; ); 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 8. CARF Canada. Aging Services Program Descriptions. 2016. Available at: http://www.carf.org/ASProgramDescriptions/. Accessed January 20, 2016. Updated November 29, 2016.

- 9. Accreditation Canada. Qmentum. Available at: https://accreditation.ca/qmentum. 2013. Accessed January 20, 2016. Updated November 29, 2016.

- 10. Bender D, Holyoke P. Bringing person and family-centred care alive in home, community and long-term care organizations. Healthc Q. 2016;19(1):70–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sumsion T, Smyth G. Barriers to client-centredness and their resolution. Can J Occup Ther. 2000;67(1):15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bruce B, Letourneau N, Ritchie J, et al. A multisite study of health professionals’ perceptions and practices of family-centered care. J Fam Nurs. 2002;8(4):408–429. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wilkins S, Pollock N, Rochon S, Law M. Implementing client-centred practice: why is it so difficult to do? Can J Occup Ther. 2001;68(2):70–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rosenbaum P, King S, Law M, King G, Evans J. Family-centred service. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 1998;18(1):1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Viau-Guay A, Bellemare M, Feillou I, et al. Person-centered care training in long-term care settings: usefulness and facility of transfer into practice. Can J Aging. 2013;32(1):57–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Edvardsson D, Winblad B, Sandman PO. Person-centred care of people with severe Alzheimer’s disease: current status and ways forward. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7(4):362–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kitwood T. Dementia Reconsidered: The Person Comes First. Buckingham, England: Open University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Saint Elizabeth. Client-centred care in the Canadian home and community sector: a review of key concepts. 2011. Available at: www.saintelizabeth.com/pfcc/resources. Accessed November 29, 2016.

- 19. Brown D, McWilliam C, Ward-Griffin C. Client-centred empowering partnering in nursing. J Adv Nurs. 2006;53(2):160–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cott CA. Client-centred rehabilitation: client perspectives. Disabil Rehabil. 2004;26(24):1411–1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Registered Nurses Association of Ontario. Client Centred Care. (rev. suppl.). Toronto, Canada: Registered Nurses Association of Ontario; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Creswell JW. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Denscombe M. The Good Research Guide: For Small-Scale Social Research Projects. 2nd ed Buckingham, England: Open University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario. Developing and Sustaining Interprofessional Healthcare: Optimizing Patients/Clients, Organizational, and System Outcomes. Toronto, Ontario: Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Virani T. Interprofessional Collaborative Teams. Ottawa, Canada: Canadian Health Services Research Foundation & Canadian Nurses’ Association; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Drynan D, Murphy S. Understanding and Facilitating Interprofessional Education: A Guide to Incorporating Interprofessional Experiences into the Practice Education Setting, second edition. Vancouver, Canada: University of British Columbia, College of Health Disciplines; 2013. Available at: http://physicaltherapy.med.ubc.ca/files/2012/09/IPE-Guide-2nd-ed.-May-2012.pdf. Accessed June 18, 2016. Updated November 29, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 27. BC’s Practice Education Committee. Advancing teamwork in healthcare. A guide and toolkit for building capacity and facilitating interprofessional collaborative practice and education 2013. Available at: http://www.dal.ca/content/dam/dalhousie/pdf/healthprofessions/Interprofessional%20Health%20Education/BCAHC%20-%20IPE%20Building%20Guide%20-%20January%202013-1.pdf. Accessed June 18, 2016. Updated November 29, 2016.

- 28. Alzheimer Society of Canada. All About Me. 2015. Available at: http://www.alzheimer.ca/en/Living-with-dementia/I-have-dementia/All-about-me. Accessed June 17, 2016. Updated November 29, 2016.

- 29. iSixSigma. Kaizen Event. 2016. Available at: https://www.isixsigma.com/dictionary/kaizen-event/. Accessed June 17, 2016. Updated November 29, 2016.

- 30. DiGioia AM, Greenhouse PK, Chermak T, Hayden MA. A case for integrating the patient and family centered care methodology and practice in Lean Healthcare Organizations. Healthcare. 2015;3(4):225–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Brown M, ed. Health Care Marketing Management. Gaithersburg, Maryland: Aspen Publishers; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Maben J, Peccei R, Adams M, et al. Patients’ Experiences of Care and the Influence of Staff Motivation, Affect and Wellbeing. Final Report. NIHR Service Delivery and Organisation Programme; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 33. The King’s Fund. Patient-Centred Leadership: Rediscovering our Purpose. 2013. Available at: http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/files/kf/field/field_publication_file/patient-centred-leadership-rediscovering-our-purpose-may13.pdf. Accessed March 29, 2016. Updated November 29, 2016.