Abstract

The societal changes in India and the available variety of reproductive health services call for evidence to inform health systems how to satisfy young women’s reproductive health needs. Inspired by Foucault’s power idiom and Bandura’s agency framework, we explore young women’s opportunities to practice reproductive agency in the context of collective social expectations. We carried out in-depth interviews with 19 young women in rural Rajasthan. Our findings highlight how changes in notions of agency across generations enable young women’s reproductive intentions and desires, and call for effective means of reproductive control. However, the taboo around sex without the intention to reproduce made contraceptive use unfeasible. Instead, abortions were the preferred method for reproductive control. In conclusion, safe abortion is key, along with the need to address the taboo around sex to enable use of “modern” contraception. This approach could prevent unintended pregnancies and expand young women’s agency.

Keywords: reproductive decision making, contraception, abortion, agency, rural India, reproductive health policy, qualitative in-depth interviews

Introduction

India is home to one of the world’s largest youth populations, where 358 million young people (10–24 years) represent 20% of India’s population (United Nations Children’s Fund [UNICEF], 2011). One third of married rural girls are adolescents (10–19 years) and early conception is common (Government of India, 2014). The government of India recently launched a comprehensive Adolescent Health Strategy, recognizing the contribution of early conceptions to ill health (Government of India, 2014). In addition to ill health, early marriage results in compromised agency and autonomy. An Indian multi-state study shows the associations of early marriage with reduced levels of autonomous decision making and with self-efficacy. Women who married early were less likely than other women to report confidence in, for example, expressing their opinions to elders (Santhya, Rajib Acharya, Jejeebhoy, Ram, & Singh, 2010). The National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) in India provides a variety of short- and long-acting contraceptive methods, and abortions are legal up to 20 weeks (Hirve, 2004). In spite of these efforts, early pregnancies remain and are influenced by early marriage, and unmet need for family planning (NRHM, 2010). However, India predominantly focuses on population control through sterilization and incentivized sterilization targets. These efforts have sometimes led to women not receiving abortion care unless they accept subsequent sterilization (Jeffery, Jeffery, & Lyon, 1985; Shaw, 2004). The long-term focus on sterilization is reflected in the high prevalence of female sterilization in India (34% of currently married women aged 15–44; Ram et al., 2009). Although awareness of contraceptive methods has increased, a subnational mixed method study shows young people’s unfamiliarity with how to effectively and correctly use, or access, reversible contraceptive methods (Santhya, Acharya, & Jejeebhoy, 2011). In addition, women who marry early are less likely to use contraceptives to delay their first pregnancy as compared with women who marry after the age of 18 (Santhya et al., 2010; Speizer & Pearson, 2011). To understand why these reproductive health issues remain despite the increased political focus on youth, to go beyond the numbers summarized above, careful attention to the social context and the young peoples’ voices is essential.

Access to reproductive health in India is shaped by the interplay between economic status, gender, education, social status, and age where adolescents have less access compared with older age groups (Sanneving, Trygg, Saxena, Mavalankar, & Thomsen, 2013). Young Indian women express fear, discrimination by doctors, and the lack of confidentiality as major barriers to accessing reproductive health services (Shaw, 2004; Singh & Srinivasan, 2000). This results in women’s preference of using “traditional” or “natural” methods in reproductive matters (Shaw, 2004; Singh & Srinivasan, 2000). The continuously expanding variety of reproductive health services available may not always be accessible to, acceptable for, or accepted by young people, especially in rural settings (Unnithan-Kumar, 2004b). Past research suggests that norms of what it means to be a good wife and mother, and notions of self and collective responsibility influence women’s non-use of contraception (Unnithan-Kumar, 2004a). Jeffery and colleagues (1985) suggest that women living in the rural north and north-western India have remained under the control of domestic authorities, specially husbands, fathers, and in-laws, giving young women little opportunity to exercise their reproductive rights (Jeffery et al., 1985). This begs the question how exactly today’s young women in rural areas of India access contraception and choose their means of fertility control.

Since legalization of termination of pregnancy in 1971, new technologies—medical abortion and manual vacuum aspiration (MVA)—have emerged and been included in the Indian abortion guidelines (Parliament of the Republic of India, 2002; World Health Organization, 2012). However, sharp curettage (D&C) is still widely practiced and accepted (Hirve, 2004). The recent political focus on sex-selective abortions due to son-preference has limited access to abortion and decelerated implementation and update of abortion methods (Ganatra, 2008; Unnithan-Kumar, 2010). This article asks how young rural Indian women make reproductive decisions and negotiate childbearing and reproductive agency; under what circumstances are abortion and contraception practiced? What are the contextually accepted means of family planning? Which contraceptive methods are available to young people, given the new and enabling policy environment and the wider range of methods in the market?

Conceptual Framework

Women’s capacity to make decisions, especially in terms of sexual and reproductive health has been analyzed under the concept of “agency.” In this study, we explore women’s agency by applying a conceptual framework informed by Foucault’s idiom of microphysics of power (Foucault, 1977) structured under Bandura’s “agentic perspective” (Bandura, 2001). Foucault’s idiom on microphysics of power argues that a power is strategic and tactical rather than acquired, preserved, and possessed. The idiom is therefore suitable when describing power dynamics at the micro-level, here referring to the community and family setting (Foucault, 1977). Strategies can be defined as conscious deliberate series of plans to achieve a defined vision whereas tactics are defined as defensive and reactive practices (Cornwall, 2007). In terms of reproductive agency, power acts through strategies and tactics where tactics are resorted to when the intentional plan fails, or when means to successfully implement the intentional plan are limited (Cornwall, 2007). Maxwell and Aggleton (2010) argue that agency is a form of power and can be seen as either a resource that is shared between people—collective, or a capacity of the self—individual. A key feature of personal agency is the power to originate actions for given purposes (Bandura, 2001). To better understand the underlying components that result in an action or the deliberate lack of an action, we use Bandura’s “agentic” perspective that stratifies agency into four components: forethought, intentionality, reactiveness, and self-reflection (Table 1; Bandura, 2001). Keeping in mind that unless people believe they can produce desired results by their actions, they have little incentive to act in the face of difficulties (Bandura, 2001). Applying strategies and tactics under the concept of agency is useful to disentangle women’s capacity to make reproductive decisions and hence understand what influences the choices available to them.

Table 1.

An Overview of the Agency Components Based on Bandura’s “Agentic Perspective” (Bandura, 2001).

| Agency Component | Description |

|---|---|

| Forethought | Reflection to consider what is known, the believed consequences of action or non-action. Forethought provides direction and coherence. |

| Intentionality | Choosing to act to achieve a certain outcome. The chosen act may be a result of acting in an accommodative way, primarily fulfilling expectations of others, or in a self-influential way fulfilling the desire of one self. |

| Reactiveness | Shaping the appropriate course of action and regulating execution. |

| Self-reflection | Judging the correctness of the action by comparing the outcome with the intention and the reaction from others as a response to the outcome or the action. |

Bandura’s “agentic perspective” was adapted to fit the Indian context taking individual and collective agency into account (Omer-Salim, Suri, Dadhich, Faridi, & Olsson, 2014). The existing literature on women’s agency and reproductive decision making in the rural Indian context refers to data collected 10 to 20 years ago and has little reference to health system implications. With the recent policy focus on the health of young people, it is important to identify barriers and facilitators to sexual and reproductive health and rights. Given the changes in sexual practices and the development in reproductive health services in India over the past 20 years, it is likely that perceptions and actions among rural youth have changed. Moreover, it is important to explore young women’s reproductive choices from an “agentic” perspective to understand their opportunities and needs in relation to the power structure in which they exist. Understanding women’s opportunities to enact reproductive agency can inform health systems in their provision of reproductive health services to young women, and thus, achieve the set out “family planning vision 2020” (Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, 2014). Thus, this article explores how young women practice fertility control, in a context where women have seemingly little autonomy, by understanding the reproductive intentions, desires, and choices available to women in relation to social expectations and accessible health services.

Materials and Method

Study Setting

The study was conducted in the rural areas of Udaipur, in southern Rajasthan, a state in the northwest of India. Rajasthan’s population is largely rural (71% of households) and livelihood depends on agriculture. The average household comprises five members, and 19% of households belong to scheduled castes, 14% to scheduled tribes (ST), 45% to other backward castes (OBC), and Rajput largely comprises the remaining 22%. Literacy rates have risen for both men and women (74% and 36%, respectively) in recent years and more children are enrolled in schools, however few complete more than 8 years. Still, the overall health outcomes are lagging behind. The maternal mortality rate is one of the highest in India (318/100,000 live births) and early marriage is common (NRHM, 2010). Majority of the population in the selected study area belong to the ST group and Rajput group. Rajputs, traditionally known as the royal warrior caste, still benefit a high social status and are historically landowners, whereas people from ST backgrounds rarely own land. Instead, they work as daily labor workers or migrate to the bigger cities. The study area lies in the Araveli mountain range and is characterized by poor road connections, poverty, and lower literacy than state average, in particular among women. The study site was chosen due to its characteristics (women’s limited autonomy, the early age of marriage, poor maternal health outcomes), the presence of different social groups, and the challenging geographical landscape and infrastructure, hampering access to health services.

Study Participants

The interviewees were identified through snowballing or with the help from the gatekeepers known in the study area. The gatekeepers were field staff from the non-governmental organization (NGO), associated village health workers or Aanganwadis, local health volunteers. We conducted interviews with married young women in the ages of 18 to 24, with a preference to those recently married or recently cohabiting. We defined “recently married” as married within the last 2 years, however, because some marriages occur very early in this region, women who were married at a young age but had only been cohabiting for the past 2 years were also included in the study. All participants were Hindu, and their socio-demographic characteristics are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Informants (n = 19).

| Age | Education (Years) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 18–20 | 11 | None | 8 |

| 21–23 | 5 | 1–6 | 5 |

| 24–25 | 3 | 7–9 | 4 |

| 12 | 1 | ||

| Caste | Husband Has Migrated | ||

| Rajput | 7 | Yes | 3 |

| ST | 11 | No | 16 |

| Other | 1 | ||

| Years of Marriage | Parity | ||

| 0–2 | 6 | None | 3 |

| 3–5 | 10 | Pregnant | 8 |

| 6–10 | 3 | 1 child | 7 |

| >2 children | 1 | ||

Note. ST = scheduled tribe.

Data Collection

To realize the study, we collected data using qualitative in-depth interviews (IDIs). Data collection was inspired by naturalistic inquiry, allowing a dynamic interview process (Guba & Lincoln, 1989). In total, 24 interviews were conducted with 19 women. Five of the women were interviewed twice; the second interview took place approximately 1 year after the first. The first round of interviews was conducted in April to May, 2013, the second round in November to December, 2013, and the follow-up interviews in April 2014. The follow-up interviews were conducted with women from the first round of interviews to elaborate on topics not sufficiently explored in the first round, or topics that emerged in the second round of interviews and needed further exploration. In addition, extracts were verified during the second round and follow-up interviews to ensure reflexivity of the data. When we considered that we had reached “topical saturation”—when the content of the interviews reflected repeated expression of women’s experiences with regard to the topics of interest (Guba & Lincoln, 1989)—we stopped data collection. The first author (Mandira Paul) carried out multiple field visits during her time in the study setting (2012–2014), visiting participants’ villages as well as other villages in the area to better understand the context and setting. This was done before and during the data collection for the purpose of this study as well as other fieldwork carried out in the area. Field visits included informal conversations with village health workers, Aanganwadi workers, elderly, and community leaders. A field diary with reflections and experiences was kept and used in the interpretation and contextualization of data. In addition, during the interviews, we occasionally visited and informed neighbors about general reproductive health awareness to relieve the study participants from unwanted attention from relatives and neighbors. These visits also contributed to the field observations.

The interview topic guide was a combination of general topics and semi-structured open-ended questions. Topics covered included personal experiences of marriage and life before and after marriage; spousal relationship, reproductive strategies, and family planning; and social expectations of reproduction and general reproductive knowledge. We also talked about autonomy, freedom, and restrictions within and before marriage. The naturalistic inquiry approach allowed the interviews to develop in stages: The initial interviews had a broad approach trying to gather general information as well as understand how to address the taboo study topic. During the course of data collection, the question guide was tightened and the topics were narrowed down. In addition, we created vignettes based on field experiences and some of the early interviews with the women, these are presented as supplementary material (Table S1). This was useful when discussing sensitive topics as well as an attempt to decrease social desirability. The first author (Mandira Paul), a young Swedish-born woman with Indian background, moderated the interviews together with the fifth author (Sunita Soni), an Indian young woman residing and working in the study area and acted translator for the purpose of the study. Interviews were carried out by using a mix of Hindi, Mewari, or other local dialects. Due to the format of the interviews and the characteristics of the interviewers, we managed to create a comfortable and friendly atmosphere rather than a formal interview. Each interview took 25 to 50 minutes, depending on the availability of the participant as well as the possibility to maintain confidentiality given the busy family setting. Interviews were tape-recorded. One woman disagreed to be tape-recorded and notes were taken. Interviews were transcribed verbatim and translated to English by a local translator with field experience. Moreover, we selected transcripts for back translation and compared these with their tape-recording to verify the quality of the translation as well as to clarify ambiguities in the interpretation of certain expressions. We found no major discrepancies and felt confident with the quality of the translation.

Ethical approval was obtained from the local institutional ethics committee in April 2013. Written consents were obtained from all participants. Majority of participants live in joint families and if a relative or a neighbor joined the discussion, the interview was considered to be over. We referred women who wanted to know more about contraception or reproductive services to seek care at the health centers nearby, or because we commonly arrived with a village health worker or an NGO worker, they could provide information and sometimes methods to the women in connection with the interview.

Data Analysis

Thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) was used to structure data into codes, sub-themes, and themes. Anonymous transcripts were read through several times and discussed between co-authors, the person who transcribed the interviews, and people working in the Indian setting. We identified codes contributing to the purpose of the study and structured them under sub-themes that captured the overarching meaning of the codes. Analysis was done manually with constant comparison between the data throughout data collection. This enabled us to confirm trends identified in the data with the subsequent interviews and additionally clarified in the follow-up interviews. Once we identified the sub-themes, we re-read the material to find extracts highlighting and confirming the findings. All authors discussed the sub-themes, which resulted in the identification of the main theme. Colleagues working in the study setting and the translator verified the meaning of the extracts.

Findings and Discussion

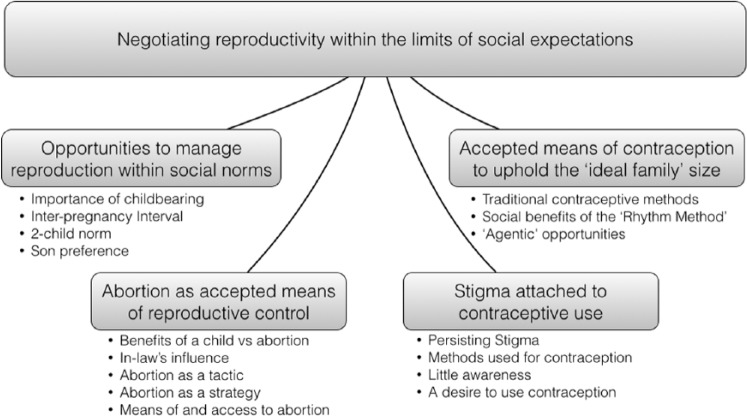

Data analysis resulted in one main theme—negotiating reproductivity within the limits of social expectations—and four sub-themes (Figure 1). The findings are structured according to the sub-themes, presenting the existing social norms of reproduction, the strategies and tactics used by women and their families to control reproduction, and the available means and different methods used by women in an attempt to plan and control fertility. These findings are discussed through a lens of agency next.

Figure 1.

Thematic map illustrating the overarching theme, the four sub-themes and a selection of codes leading up to the sub-themes.

Opportunities to Manage Reproduction Within Social Norms

Having children was primarily essential to fulfill social responsibilities and invest in the future. However, women also desired children. Childbearing was used a strategy by women to improve their social status, and prove womanhood. When asked what was “good” about having a child, one interviewee who had not yet conceived explained, “It’s the tradition of the society, if a child is not there then society speaks bad. People can say anything,” she later added, “ . . . but, a child is our happiness too . . . There is a responsibility to grow them up, and it feels good” (20 years, nulliparous, Rajput). The social pressure to have children often overruled the couples’ private agenda, and recently married couples had to compromise their own desire with social expectations. However, there were opportunities to negotiate reproduction within the social norms. One interviewee belonging to the Rajput social group explained, “I was afraid if something [pregnancy] would happen this early [within one year of marriage], in our caste it is not allowed to conceive this early . . . but then also, he was born in one year [laughs]” (24 years, uniparous, Rajput). Managing reproduction according to social norms was not easy; one child was expected after cohabitation; however, not necessarily “too” soon. In most cases, there was a window of opportunity to delay having a child for approximately 2 years. This implies that young Indian women are still tied by social structures informing and influencing their reproductive intentions. One woman explained, “when she [the daughter] will become 5 years old, . . . , then it would be fine [to have another child]” (19 years, uniparous at follow-up interview, ST). Hence, once a child was born there was less pressure to have another, and having one child was a way of “buying time” to be able to wait to conceive again. Participants knew of and referred to spacing between children, generally a 2- to 5-year gap to ensure health of both mother and child. Spacing of children could be socially justified by the known and accepted health consequences of frequent births; short inter-pregnancy intervals were frowned upon. Our findings clearly demonstrate the successful social internalization of the government’s past efforts to promote the two-child norm and inter-pregnancy intervals (Jeffery et al., 1985). The social acceptance of these childbearing norms in rural Rajasthan enables a collective approach toward reproduction that is directly beneficial to women’s health, allowing women more reproductive autonomy, while staying within the limits of social expectations. Hence, women’s personal reproductive intentions to space and limit number of children accommodate the accepted social norms and result in a beneficial environment for the women, catering to their own and their communities’ reproductive desires. This may enhance the scope of fertility control among recently married women. In line with previous research, this new beneficial environment could result in an earlier resort to contraception than currently seen, given the access to appropriate contraceptive choices and counseling (Edmeades, Lee-Rife, & Malhotra, 2010). Importantly, this gives the health system an opportunity to provide women with effective strategies to achieve delay and spacing of children, in accordance with the current social norms.

An “ideal family” according to the women, consisted of two children—one boy and one girl. However, participants accepted any sex of the baby because they understood that this could not be controlled. Only one woman (22 years, pregnant, Rajput) stated that a son is necessary and mentioned sex-selective abortions, referring to machines in the city that can establish the sex of the child, as a last resort. When probed, another participant said, “As I’m having a daughter, so if I have a son then it will be better. We need one boy and one girl” acknowledging the benefits of a son. However, when we asked her what to do if the second child was a daughter too she answered, “Then what can be done, it’s the God’s wish.” She further explained that her mother had seven daughters, and that there was no point to continue to have children until you conceive a boy. Even her “husband has said that there is no problem if one boy and one girl is not there, two girls will also do” (19 years, uniparous, ST) suggesting that in the case of this family, there was no pressure to have boy children from the father. Another woman (24 years, uniparous, Rajput) stated, “After two children I want to sterilize, regardless of sex of the children,” suggesting family size to be more important than the sex of her children. Although most participants did not express an explicit son-preference, they appreciated the social value of having a boy and were aware of its social benefits. However, the strong son-preference as previously reported (Jeffery et al., 1985), seems to be fading over generations. Bearing in mind that Jeffery and colleagues did their research in another Indian state where attitudes may differ and acknowledging the possibility of social desirability by non-disclosure of son-preference among participants. A recent multi-state survey showed that Rajasthan had the lowest proportion of men and women with high son-preferring attitudes and that men and women who desired more sons were typically older (Priya et al., 2014), supporting our findings of an attitude transformation among younger men and women.

Abortion as Accepted Means of Reproductive Control

The women had reproductive visions and a desired family size that was influenced not only by social norms but also by personal reproductive intentions. Conversely, the women rarely had an effective strategy to enact their intentions. Several participants had experienced an unintended pregnancy resulting in childbirth or abortion. One woman, who had not experienced an abortion, explained, “The women talk about cleaning, safai, [abortion] . . . if they do not want the child, then they have to go for safai” (24 years, uniparous, ST). This reflects the general attitude to abortion among the participants, indicating acceptance toward using abortion to control reproduction. However, because an Indian woman’s body has many stakeholders (Unnithan-Kumar et al., 2004), reproductive decisions among participants were made under the duress of collective intentionality.

Although participants accepted abortions, their families did not necessarily accept abortions under all circumstances, especially not if the woman was nulliparous or a child was anticipated. Having an abortion was rarely a decision made in agreement with the mother-in-law. Instead, when the mother-in-law knew about the pregnancy, an abortion was less likely. Some of the participants had aborted their first pregnancy, regardless of it being considered controversial. One participant explained to her husband about her unintended pregnancy that she perceived to have occurred “too soon,” at the age of 17:

I told him that this has happened to me, I’m three months pregnant. And if someone will see and will ask, how this happened . . . I don’t want it now, so he agreed with me. I went there [to the clinic] . . . Then I took the pills and had a cleaning, and my work [abortion] was done with it. (19 years, pregnant at first interview, ST)

Another participant (21 years, pregnant, ST) chose to exclude her husband from the decision to abort her first pregnancy at the age of 19. She had been married for 4 years, and lived and worked with her husband in the city since 2 years. She felt the need to keep the abortion a secret because, she had been cohabiting with her husband for 2 years, and a child was anticipated. She thought she was too young to conceive and that an early pregnancy could be harmful. She was pregnant again at the time of the interview: “I wanted to [abort again], but then I get to know that this harms the body if you will do it repetitively and I got afraid. Let it happen” (21 years, pregnant, ST). The rumors of abortions being harmful, her mother-in-law’s awareness of the pregnancy, and the husband’s desire to have a child changed her mind to keep the second pregnancy. Women discussed abortions with their husbands, or conducted abortions according to their own wish, given that the mother-in-law was unaware. Both examples above describe individual, self-influential, intentionality in the attempt to practice agency and reproductive control. Abortions were common solutions to unintended pregnancies, accepted by women and mostly by their husbands too. This suggests that women primarily use abortion as a means of reproductive control, and not for the purpose of sex selection. Our findings contrast the recent medial and political focus that suggests abortions to primarily be sex selective and claims abortions to be the exclusive explanation for India’s declining sex ratio (Ganatra, 2008). Hence, our findings emphasize the importance of available safe abortion services as means of reproductive control. Recent studies from Rajasthan suggest the efficacy, feasibility, and acceptability of implementing and scaling up of early medical abortion in primary health care settings offering different modes of follow-up to decrease number of clinical visits and increase the women’s autonomy in the abortion procedure (Iyengar et al., 2015; Paul et al., 2015). This could further enable women’s agency in reproductive decision making.

Women used different methods for inducing abortions, however all abortions were referred to as “cleaning,” safai. This suggests that medical abortion, similar to surgical abortion (Unnithan-Kumar et al., 2004), is culturally accepted due to the perception that medical abortion cleans the uterus. Some interviewees explained that they sought abortion from the nearby NGO-run clinics, others traveled to private clinics in Udaipur City, some received pills from their husbands or bought them from a medical shop, and one woman ingested heated sugar from dates, jaggeri, and confirmed the successful termination of her pregnancy. One woman who miscarried, primarily sought cleaning from a public health facility nearby, but she perceived the care to be insufficient and continued to seek care from a private clinic in the city to get a “proper cleaning done,” and thus ensure future conception. Some women seemed confused whether they had taken abortion or contraception pills. When we asked about contraception, one participant explained, “I have taken tablets before. [With] tablet [I] mean [the tablet you take] when the period days have crossed [delayed]. Then I took the tablets once” she further explained, “my husband has said [husband’s idea], he bought the tablets from the shop or from the hospital, that I don’t know, I took them at home” (24 years, uniparous, Rajput). Interestingly, few participants related abortion to danger, especially when the women obtained the abortion from a health facility or by using pills from what they considered a safe provider or brought to them by their husbands. Previous research focuses on the unsafe means of abortions that Indian women use (Banerjee, Andersen, & Warvadekar, 2012; Duggal & Ramachandran, 2004), however to our knowledge, little light is shed on women’s perception of whether these means of abortions are unsafe or not. Our research suggests that women in this setting do not perceive seeking abortion from different sources as unsafe, however they refrain from resorting to the public health facilities for abortion care. Conversely, the vulnerability of women is evident through their dependence on private or informal abortion providers and their husbands to obtain abortion services. In line with our study, previous research also suggests women’s unwillingness to seek abortion in the public health sector due to their lack of privacy, forced adoption of contraception or sterilization, and poor quality services (Shaw, 2004; Singh & Srinivasan, 2000).

Although women conducted most abortions without the involvement of the mother-in-law, there were cases where abortions served purpose of the collective intentionality, and instead of the woman’s intention to terminate the pregnancy, the mother-in-law was the initiative taker. One woman had conceived “too early”—before cohabitation—and the mother-in-law decided to take her to the clinic to terminate the pregnancy, to maintain the family reputation. Another woman had been forced by her parents-in-law to have an abortion after she experienced bleeding in the second trimester. The woman did not consent to the abortion; nevertheless, it was conducted in a public hospital using D&C, with no anesthesia. The husband was neither at home nor informed until after the abortion. The woman received little support afterwards and was now scared of difficulties to conceive again. Hence, in contrast to women’s tactic use of abortion, in-laws could strategically use abortions, by demanding the woman to abort the pregnancy if they found the pregnancy inappropriate. Previous research suggests sex-selective abortions to be a result of women’s lack of reproductive agency and family pressure (Unnithan-Kumar, 2010). However, to our knowledge, the literature does not illuminate when family members demand women to conduct abortions for purposes other than sex selection. Such abortions further stress the vulnerability of young women, and the lack of access to self-controlled, evidence-based methods of abortion jeopardizes women’s reproduction and health. Methods of abortions need to be not only safe and evidence-based but also correctly applied by the collective and made accessible to women, for them to successfully control their reproduction, individually and collectively.

Our findings emphasize the importance of scaling up acceptable and non-discriminatory abortion services within the public health system, in line with previous suggestions to improve abortion care in India (Ganatra, 2008). Moreover, the central role of men as providers of abortion pills and the parents-in-law resort to abortion sheds light on the need to increase knowledge of reproductive health services including abortion in the community. Women who use abortion to achieve self-attainment should not mean that women have to jeopardize their health and future reproduction due to the lack of access to safe abortion services. In the context of Bandura’s “agentic perspective,” abortion can be seen as a result of self-reflection where social expectations and collective reproductive intentions are weighed by the woman in retrospect of knowing of the pregnancy, ultimately resulting in accommodative agency—to continue the pregnancy, or self-influencing agency—to terminate the pregnancy. This decision depends on the available opportunities of reactiveness and the stakeholders involved in the decision-making process, deciding whether the action responds to the collective or the individual reproductive intentionality. Hence, abortions were a reactive means of reproductive agency, tactically used by women to stay within the limits of social expectations, informed by appropriate timing of a child, the two-child norm, and the reproductive intention of the woman.

Accepted Means of Contraception to Uphold the “Ideal Family” Size

In an attempt to uphold reproductive norms and expectations, the women used socially accepted “traditional” contraceptive methods in addition to abortions. These methods refer primarily to abstinence during fertile days—the “rhythm method”—however, homeopathic contraception or “coitus interruptus” were also mentioned as socially accepted methods, although rarely used among the participants . The women had learnt from sisters, friends, or elderly that conception was only possible during a certain time of the month, the 10 to 15 days starting from the first day of menstruation. It was understood that menstrual bleeding cleans the uterus from dirt and leaves the uterus open and receptive for sperm. Women had different strategies to implement the “rhythm method,” and it was common to return to the natal home during the “fertile days.” One woman explained, “I didn’t go near my husband, I came here [in-laws] and when period comes then I go there [natal home] for 5 to 7 days” (19 years, uniparous, ST). This moving back and forth between family homes was useful until the in-laws or the community thought it was time for the woman to conceive, and subsequently limited her travel opportunities. Participants, who did not return to their natal homes, explained that they abstained during the “fertile days.” When asking whether their husbands respected the periodic abstinence, one woman explained, “He takes care of . . . meaning [when] I refuse [sex] then he agrees with that” (24 years, uniparous, Rajput). Indicating that having a husband who agreed with periodic abstinence to avoid pregnancy did not imply mutual responsibility to abstain, rather an acceptance if the woman actively refused sex. Another woman described the difficulties with maintaining periodic abstinence as follows:

Yes, he agrees [with using the rhythm method] but he used to come daily [to try to have sex] and I used to fight with him [to avoid sex]. I will get pregnant again with a son, then, that’s why [he should not try to have sex with me]. (19 years, uniparous, ST)

She explains how she has to fight off her husband, even though he agreed to use the rhythm method to avoid pregnancy. This suggests that practicing periodic abstinence could result in arguments between husband and wife and that women felt frustrated in their management of periodic abstinence. Still, none of the interviewees suggested “modern” reversible contraceptives or condoms as a feasible alternative or complement to the “rhythm method.”

The periodic abstinence gave women an accepted reason to return to their natal homes or to refuse sex. The period of abstinence varied depending on the time that women wished to stay at their natal homes or abstain from sex with their husbands. The “rhythm method” therefore gave women an opportunity to regain power in their spousal relationship. In addition, the women perceived the method as their most or only, feasible means of fertility control. However, in practice, the failure to convince the husband to abstain, the failure to count the days correctly, and the misunderstanding of the ovulation cycle enhances the ineffectiveness of the “rhythm method.” Even with correct use, periodic abstinence has 3 times the odds of resulting in unintended pregnancies compared with modern contraception (Bellizzi, Sobel, Obara, & Temmerman, 2015). The rhythm method did not serve women’s reproductive intentions effectively; however, it enabled “agentic” opportunities within their relationships. Conception was not perceived as a shortcoming of the “rhythm method,” but rather a personal failure to abstain or count the days correctly. It is important to recognize what women perceive are their feasible choices of fertility control in the health care encounter. However, it is also important to provide accurate information with regard to “traditional” methods of contraception as well as options of modern reversible contraceptive methods. This is in line with recent research suggesting that health personnel should inform women about the correct ovulation cycle for better understanding of reproduction (Ram, Shekhar, & Chowdhury, 2014). This was also supported by the women’s requests to know more about means of contraception, in connection with the interviews. The “agentic” opportunities provided by the rhythm method can be attributed to the justified visits to women’s natal home, where women are known to have more freedom and less obligations (Jeffery & Jeffery, 1996) or through prolonged periods of abstinence. Unnithan-Kumar (2004b) writes that women living in settings with little autonomy or decision-making power tend to find alternative channels to influence and communicate their approval or disapproval of an action, for example, women can realize agency through the resistance to cooperate (Unnithan-Kumar, 2004a).This is in line with the two kinds of reactiveness—accommodative or self-influencing—that shape appropriate course of action (Bandura, 2001). Hence, women may use the non-use of contraception as a means to practice agency in their family setting. This perspective underpins the need to empower women to fulfill their sexual rights without having to justify them with reproductive control. Furthermore, it must be considered in the provision of contraceptive counseling and other reproductive health services.

Stigma Attached to Reversible Contraceptive Use

Women were in search of accepted and effective means to control their reproduction, and there was a notion of wanting to use modern contraception, however not clearly outspoken among the interviewees. Only two participants (20 years, uniparous, ST; and 24 years, uniparous, Rajput) mentioned sterilization or operation as their future means of family planning, where one of the women explained that she planned to be sterilized after the second child because her family situation would never allow her to use reversible contraception. The other participants had not yet thought of strategies to limit childbearing, or preferred alternative methods. In contrast to abortion and sterilization that were relatively easy to talk about, when discussing reversible contraception with the participants, they initially became few worded and silences between answers were longer. A 19-year-old woman (ST) disclosed that she knew of other women who used oral pills and that she too was considering using it, now that she had conceived once. Another participant explained as follows: “Yes, I’ve heard [about contraception], but I’ve never thought of taking any tablet.” We continued to ask whether her husband had ever suggested any contraceptive method and she said,

He said [suggested], but I refused, there is no fear, but I didn’t take . . . My in-laws got to know . . . What ever contraceptive I take, they get to know; then they can tell anyone, so I didn’t take. Even my [natal] family members have told me [not to take]. (20 years, uniparous, ST)

The oral pill, Mala-D, was the most frequently cited contraceptive method among the women, whether used or not. Two women had tried the 3-month injection and a few knew of the copper intra-uterine device, Copper-T; however, none had used it. Several women claimed to never have heard of condoms, nirodh, and those who knew only mentioned it when we probed. Women, whose husbands worked in the city, said that “it would not look good” if they took pills while the husband was away, although they expressed a need for contraception when the husbands visited. Interestingly, some women who had experienced an institutional birth claimed to not have heard of contraception, however women who had conceived were more open to discuss reversible contraception. The reluctance to demonstrate awareness or experience illustrates persisting stigma and controversy around using and talking about contraceptive methods, also suggested by Unnithan-Kumar (2004b) in her fieldwork 15 years ago. The health services encounter must not re-enforce the persisting stigma on reversible contraception. Instead, contraceptive services must ensure women’s comfort and privacy. Moreover, services must acknowledge and use the opportunity offered post-partum and post-abortion when women may be more motivated to adopt a contraceptive method (Gemzell-Danielsson, Kopp Kallner, & Faúndes, 2014; Sebastian, Khan, Kumari, & Idnani, 2012). Recent research carried out in the same study area by the first author (Mandira Paul) and colleagues (2015) shows that women provided contraceptive counseling were more likely to initiate a contraceptive method post-abortion, indicating that abortion provides an opportunity for contraceptive uptake also in the study setting. The little focus on sterilization in the interviews is in sharp contrast to the observed prevalence of sterilization in Rajasthan (47%; Registrar General and Census Commissioner, 2012). This provides a nuanced picture of young women’s contraceptive preferences and widens the scope for reproductive control beyond sterilization, indicating a need for both short- and long-acting reversible contraceptives. However, participants’ current lack of need to limit childbearing can also explain the limited discussion around sterilization, something that may change with age.

Women’s perceived lack of power to make decisions regarding future events, may explain their absence of preventive reasoning with regard to reproduction. Several participants reasoned like this woman (19 years, uniparous, ST): “I’m not using any methods, as I think till it [period] is going on like this [regularly], I’ll not use methods. As I’m having periods every month, so I’m not using anything,” implying a lack of understanding of the preventive rationale behind contraception. This raises the question whether women in our study are referring to medical abortion as a contraceptive method, or whether they discard the concept of modern contraception and prefer to act in retrospect. It may however not be a matter of preference or lack of knowledge, but rather an effect of the disbelief that an action, such as using contraception, would result in the desired result (Bandura, 2001).

Women thought the strategic use of “modern” contraception was impossible to fit under the collective decision making because the community discarded “modern” methods. This was attributed, by our participants as well as in previous research, to the families’ fear of infertility as a consequence of contraception and the social stigma attached to infertility (Kalra, 2015; Unnithan-Kumar, 2004a), as well as women’s limited knowledge of modern methods of contraception. Interestingly, participants rarely believed in the misconceptions themselves. Instead, many had a positive perception of contraception, especially oral pills, and hence tacit desires to use it. Nonetheless, there was an underlying fear:

If we [young women] use anything [modern contraception] and if later a child is not born, then it would be difficult for us. And because of that, the mother-in-law will scold you. Because you have used this [contraception], that’s why you are not having child. That’s why we have not used them. (20 years, nulliparous, Rajput, indicating that the use of contraceptive methods jeopardizes women’s social and family relationship, especially if conception did not occur as anticipated)

This is in line with our unpublished results from a recent study from Rajasthan where women were more likely to adopt “modern” contraception post-abortion if they had the intention to limit childbearing rather than to space. Hence, recently married women had insufficient agency to use contraception as a strategic means to plan their family, regardless of whether the plan would be according to social expectations or not. In addition, notions of promiscuity, to have sex for pleasure, and in-laws’ perceived lack of control of women who are using contraception, were also prominent reasons for disapproving contraceptive use. The women considered contraception, in contrast to abortion, to be difficult to keep a secret in the family setting. Consequently, women rarely perceived contraception to be a feasible strategy for reproductive control. Families’ support to use contraception deemed important, and although controversial in this setting, family planning programs must include other family members (Ram et al., 2014), while still paying attention to the woman’s demands.

The little trust in and use of the public health system with regard to reproductive matters, especially family planning, mirrored by our participants, may be a remnant from the Emergency in the 1970s. During this episode, the government introduced female sterilization as a priority family planning method (Jeffery et al., 1985), an emphasis that is still present today and manifested in incentives and governmental sterilization targets (Sebastian, Khan, & Roychowdhury, 2010). The exclusive focus on sterilization has demotivated health workers to counsel women on their choices of reversible contraception, and few women who have undergone sterilization report previous use of other contraceptive methods (Sebastian et al., 2010). It is important that the Indian health system acknowledges young women’s reproductive agency, and goes beyond the traditional perception of Indian women as passivized in the sociocultural context. The limiting of access to safe abortion services restrict women’s possibilities to practice their sexual and reproductive rights, and hence constrain their opportunities to adjust within the limits of social expectations. Concurrently, our findings of women’s reproductive agency, intentions, and the changing social norms provide opportunities for contraceptive uptake earlier in life for the purpose of delaying conception and spacing between children. However, for women to benefit from these opportunities, contraceptive services must cater to young women’s realistic choices while embracing their “agentic” opportunities, and hence both abortion and contraceptive services must be accessible. The use of reversible contraception and abortion has shown to have a positive association over the life-course among Indian women, attributed to the existing intention to plan reproduction (Edmeades et al., 2010). Women who experienced abortions are more likely to adopt contraception, and women, who used contraception that failed, are more likely to resort to abortions, compared with non-users (Edmeades et al., 2010). Thus, to embrace these opportunities of contraceptive uptake, comprehensive contraceptive counseling is crucial to increase awareness and use and must offer different contraceptive methods that cater to women’s reproductive health needs and the context in which she exists (Garg & Singh, 2014). To better understand women’s use or non-use of contraception and abortion for fertility control, we use Bandura’s (2001) concept of intentionality. Women act “accommodatively” by not opting for contraception, and hence profiting from the consequent social benefits. Instead, the women resorted to abortions as a tactical solution to unintended pregnancies, perceived to be more feasible in their context. Women in our study still managed reproductive control through the use of socially accepted means, however could choose to use abortions for the purpose of being socially accommodative or self-influential, if needed. This suggests that women do not regard all aspects of reproduction as a collective responsibility dealt with by employing collective strategies. These findings add a dimension to Unnithan-Kumar’s description of the traditional Indian conception of the body as a collective entity (Unnithan-Kumar, 2004a). In addition, it suits well with Cornwall’s suggestion of women resorting to reactive tactics, abortion in this case, rather than preventive strategies, contraception, as a means of agency (Cornwall, 2007).

Methodological considerations

This study included field observations to increase dependability by understanding the setting, cultural practices, and the language. The participants belong to different social groups; however, several are from vulnerable social groups in a challenging and poor context. Given the emerging nature of the interview process, the quality of the data retrieved, and the opportunity to confirm and further explore sensitive topics during the follow-up interviews, we believe that social desirability bias decreased, however being aware of the fact that in certain topics there may still have been such bias. We believe the findings may be transferrable to similar settings in Northern India and relevant to the general scholarship on fertility control in similar contexts, given the rich data gathered from participants belonging to vulnerable and marginalized social groups in resource-poor settings put in context with the existing literature. Due to the careful translation process and the discussion between authors and people working in the field area, we believe we have overcome the major language barriers and ensured reflexivity.

Conclusion

This study explores how young rural Indian women practice reproductive control by studying their opportunities to influence reproductive decisions. Our findings highlight the changes in notions of agency across generations, and suggest that recent social changes have created unique opportunities for young women’s influence in reproductive decision making. In spite of the collective governance of women’s bodies, especially in terms of reproduction, the changes in attitudes toward fertility control, son-preference, sterilization, contraception, and abortion give rise to new “agentic” opportunities that enable women’s individual reproductive decision making. With these new norms comes a pronounced need for effective means of reproductive control, identified by the women themselves and emphasized through their tacit desires to use contraception. However, the existing social norms also discourage contraceptive use attributed to misconceptions of infertility, and the persisting taboo of having sex without the intention to reproduce. Women perceived the use of “modern” contraception as unfeasible because regular contraceptive use was thought difficult to keep a secret, given the lack of privacy in the family setting. In contrast, “traditional” methods of contraception, complemented by abortions, were considered feasible and the best available means of reproductive control. Interestingly, the women did not always differentiate between medical abortion and contraception, and their lack of knowledge of contraceptive methods was profound.

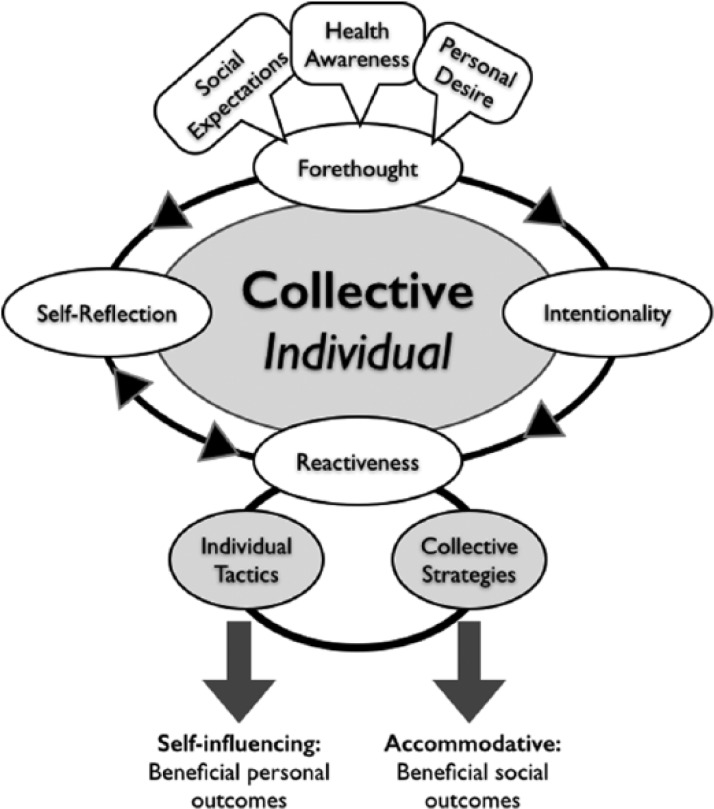

The conceptual framework used for this study is helpful to better understand the process of reproductive agency and health needs among young women. In rural India, two courses of agency are available, the collective and the individual. Both courses can be divided into Bandura’s agency components; forethought, intentionality, reactiveness, and self-reflection, and in the case of reproductive agency, we argue that these components are interrelated through a bidirectional interplay. Intentionality and self-reflection are complementary and guide reactiveness, either prospectively or retroactively. Both components are informed and influenced by existing social expectations: the biomedical concepts of delaying first pregnancy, the two-child norm, and the inter-pregnancy interval; and importantly, the woman’s own desire to reproduce (Figure 2). Instead of arguing that women fall victims for the collective reproductive agency, commonly argued in the Indian setting, we argue that today’s young rural women have reproductive intentions and increased opportunities to enact their individual agency. The reactiveness resulting from women’s intention and/or self-reflection, may then be strategic or tactic and, despite women’s limited autonomy, enables agency in the sense of Foucault (1977). Currently, for young women to enact their individual reproductive intentions, they need to apply tactics, such as abortion, to obtain self-influential outcomes, or if the woman’s intention corresponds with the collective intention, she may apply a socially accepted strategy and act in an accommodative way, resulting in beneficial social outcomes (Figure 2). However, women’s new “agentic” opportunities in reproductive decision-making identified in our study, pave way for women’s more strategic use of effective contraception when they plan their families.

Figure 2.

The adapted applied conceptual framework, schematically illustrating collective and individual agency and the interaction between Bandura’s (2001) four components of agency, the influential social factors, the tactics or strategies, and the outcomes depending on course of action: individual or collective.

The health system must embrace and encourage the need for and desire to use effective means of reproductive control among young women observed in the study. Currently, the lack of socially accepted “modern” contraception forces young women to use “traditional” contraception. Abortion therefore plays a key role in enabling young women’s individual reproductive agency, and provides a measure to remain within the limits of social expectations. Second, to avoid unwanted pregnancies and to support a shift toward “modern” contraceptive methods, it is important to recognize and address the taboo of sex without the intention to reproduce. If the health system does not acknowledge young women’s sexual needs, contraceptive counseling is unlikely to motivate young women’s use of contraception, and hence fails in its attempts to address young women’s reproductive needs. This also calls for enhanced awareness among families and at the community level, to create an enabling and supporting environment where women can use contraception. Educating families and communities is crucial to break the existing taboos around “modern” contraception. Finally, the public health system must improve its reputation in terms of reproductive health care services and shift focus from sterilization to contraception and medical abortion to attract young women to seek care in reproductive matters. Health facility and community must offer contraceptive services in a non-judgmental, patient-centered way where providers are trained to cater to young people’s reproductive needs in a changing society.

Author Biographies

Mandira Paul, MSc, PhD, candidate in International Reproductive and Maternal Health at the Department of Women’s and Children’s Health, Uppsala University, Sweden.

Birgitta Essén, PhD, is a professor in International Reproductive and Maternal Health at Uppsala University and a senior consultant in Obstetric and Gynaecology at the University Hospital of Uppsala, Sweden.

Salla Sariola, PhD, a senior researcher at Ethox Centre, Nuffield Department of Population Health, University of Oxford, United Kingdom.

Sharad Iyengar, MD, a public health doctor working on SRH issues at Action Research & Training for Health, Udaipur, India and serves as adjunct professor in Public Policy at Duke University, Durham, USA.

Sunita Soni, MSc, a senior associate at Action Research & Training for Health, Udaipur, India.

Marie Klingberg Allvin, PhD, a midwife and associate professor at Dalarna University and senior researcher at Karolinska Institutet, Sweden.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The research and the publication was funded by Swedish Research Council grant#2011-3525 and the family planning fund of Sweden. As was also specified in the submission system. In addition: Salla Sariola (3rd author) is funded by Global Health Bioethics Network, Wellcome Trust Strategic Award number 096527.

References

- Bandura A. (2001). Social Cognitive Theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 1–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S. K., Andersen K. L., Warvadekar J. (2012). Pathways and consequences of unsafe abortion: A comparison among women with complications after induced and spontaneous abortions in Madhya Pradesh, India. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 118, S113–S120. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(12)60009-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellizzi S., Sobel H. L., Obara H., Temmerman M. (2015). Underuse of modern methods of contraception: Underlying causes and consequent undesired pregnancies in 35 low- and middle-income countries. Human Reproduction, 30, 973–986. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deu348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Cornwall A. (2007). Taking chances, making choices: The tactical dimensions of “reproductive strategies” in southwestern Nigeria. Medical Anthropology, 26, 229–254. doi: 10.1080/01459740701457058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duggal R., Ramachandran V. (2004). The Abortion Assessment Project—India: Key findings and recommendations. Reproductive Health Matters, 12, 122–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmeades J., Lee-Rife S. M., Malhotra A. (2010). Women and reproductive control: The nexus between abortion and contraceptive use in Madhya Pradesh, India. Studies in Family Planning, 41, 75–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foucault M. (1977). Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison (Repr. ed.). London: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Ganatra B. (2008). Maintaining access to safe abortion and reducing sex ratio imbalances in Asia. Reproductive Health Matters, 16, 90–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg S., Singh R. (2014). Need for integration of gender equity in family planning services. The Indian Journal of Medical Research, 140, (Suppl.), 147–151. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gemzell-Danielsson K., Kopp Kallner H., Faúndes A. (2014). Contraception following abortion and the treatment of incomplete abortion. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 126, S52–S55. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2014.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government of India. (2014). Strategy handbook—Rashtriya Kishor Swasthya Karyakram (RKSK). Retrieved from http://nrhm.gov.in/images/pdf/programmes/RKSK/RKSK_Strategy_Handbook.pdf (accessed 16 Oct 2015).

- Guba E., Lincoln Y. S. (1989). Fourth generation evaluation (1st ed.). London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Hirve S. S. (2004). Abortion law, policy and services in India: A critical review. Reproductive Health Matters, 12, 114–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyengar K., Paul M., Iyengar S. D., Klingberg-allvin M., Essén B., Bring J., . . . Gemzell-danielsson K. (2015). Self-assessment of the outcome of early medical abortion versus clinic follow-up in India: A randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial. The Lancet, 3, e537–e545. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00150-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffery P., Jeffery R. (1996). Don’t marry me to a plowman! Boulder, CO: Westview Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffery P., Jeffery R., Lyon A. (1985). Contaminating states and women’s status—Midwifery, childbearing and the state in rural north India. New Delhi: Indian Social Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Kalra R. (2015). Perceptual analysis of women on tubectomy and other family planning services: A qualitative study. International Journal of Reproduction, Contraception, Obstetrics and Gynecology, 4, 94–99. doi: 10.5455/2320-1770.ijrcog20150218 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell C., Aggleton P. (2010). Agency in action—Young women and their sexual relationships in a private school. Gender and Education, 22, 327–343. doi: 10.1080/09540250903341120 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health & Family Welfare. (2014). India’s “Vision FP 2020.” New Delhi, India: Government of India. [Google Scholar]

- National Rural Health Mission. (2010). 4th common review mission of the national rural health mission—report from Rajasthan. Jaipur, India: Government of India. [Google Scholar]

- Omer-Salim A., Suri S., Dadhich J. P., Faridi M. M. A., Olsson P. (2014). Theory and social practice of agency in combining breastfeeding and employment: A qualitative study among health workers in New Delhi, India. Women Birth, 27, 298–306. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2014.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parliament of the Republic of India. (2002). The Medical Termination of Pregnancy Amendment Act, 2002 (No. 64 of 2002): An Act to amend the Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Paul M., Iyengar K., Iyengar S., Gemzell-Danielsson K., Essén B., Klingberg-Allvin M. (2014). Simplified follow-up after medical abortion using a low-sensitivity urinary pregnancy test and a pictorial instruction sheet in Rajasthan, India – study protocol and intervention adaptation of a randomised control trial. BMC Women’s Health, 14, 98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul M., Iyengar K., Essén B., Gemzel-Danielsson K., Iyengar S. D., Bring J., . . . Klingberg-Allvin M. (2015). Acceptability of home-assessment post medical abortion and medical abortion in a low-resource setting in Rajasthan, India. Secondary outcome analysis of a non-inferiority randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE, 10(9), e0133354. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priya N., Abhishek G., Ravi V., Aarushi K., Nizamuddin K., Dhanashri B., . . . Sanjay K. (2014). Study on masculinity, intimate partner violence and son preference in India. New Dellhi, India: International Center for Research on Women. [Google Scholar]

- Ram F., Ladusingh L., Paswan B., Unisa S., Prasad R., Sekher T. V., Shekhar C. (2009). District level household and facility survey fact sheets India 2007–2008 (DLHS-3). Retrieved from http://rchiips.org/pdf/india_report_dlhs-3.pdf (accessed 16 October 2015).

- Ram F., Shekhar C., Chowdhury B. (2014). Use of traditional contraceptive methods in India & its socio-demographic determinants. The Indian Journal of Medical Research, 140(Suppl.), 17–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Registrar General and Census Commissioner. (2012). Annual health survey 2012-13: Fact sheet Rajasthan. New Delhi, India: Government of India; Retrieved from http://www.censusindia.gov.in/vital_statistics/AHSBulletins/AHS_Factsheets_2012-13/FACTSHEET-Rajasthan.pdf (accessed 16 October 2015). [Google Scholar]

- Sanneving L., Trygg N., Saxena D., Mavalankar D., Thomsen S. (2013). Inequity in India: The case of maternal and reproductive health. Global Health Action, 6, 1–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santhya K. G., Acharya R., Jejeebhoy S. J. (2011). Condom use before marriage and its correlates: Evidence from India. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 37, 170–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santhya K. G., Rajib Acharya U. R., Jejeebhoy S. J., Ram F., Singh A. (2010). Associations between early marriage and young women’s marital and reproductive health outcomes: Evidence from India. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 36, 132–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebastian M. P., Khan M. E., Kumari K., Idnani R. (2012). Increasing postpartum contraception in rural India: Evaluation of a community-based behavior change communication intervention. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 38, 68–77. doi: 10.1363/3806812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebastian M. P., Khan M. E., Roychowdhury S. (2010). Promoting healthy spacing between pregnancies in India: Need for differential education campaigns. Patient Education and Counseling, 81, 395–401. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.10.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw A. (2004). Attitudes to genetic diagnosis and to the use of medical technologies in pregnancy: Some British Pakistani perspectives. In Unnithan-Kumar M. (Ed.), Reproductive agency, medicine, and the state: Cultural transformations in childbearing (pp. 25–57). New York: Berghahn Books. [Google Scholar]

- Singh L. P., Srinivasan K. (2000). Family planning and the scheduled tribes of Rajasthan: Taking stock and moving forward. Journal of Health Management, 2, 55–80. doi: 10.1177/097206340000200103 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Speizer I. S., Pearson E. (2011). Association between early marriage and intimate partner violence in India: A focus on youth from Bihar and Rajasthan. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26, 1963–1981. doi: 10.1177/0886260510372947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Children’s Fund. (2011). Adolescence : An age of opportunity. New York: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Unnithan-Kumar M. (2004a). Conception technologies, local healers and negotiations around childbearing in Rajasthan. In Unnithan-Kumar M. (Ed.), Reproductive agency, medicine, and the state: Cultural transformations in childbearing (pp. 59–81). New York: Berghahn Books. [Google Scholar]

- Unnithan-Kumar M. (2004b). Introduction: Reproductive agency, medicine and the state. In Unnithan-Kumar M. (Ed.), Reproductive agency, medicine, and the state: Cultural transformations in childbearing (pp. 1–23). New York: Berghahn Books. [Google Scholar]

- Unnithan-Kumar M. (2010). Female selective abortion - beyond “culture”: Family making and gender inequality in a globalising India. Culture Health & Sexuality, 12, 153–166. doi: 10.1080/13691050902825290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unnithan-Kumar M., Shaw A., Simpson B., Bonaccorso M., Stones W., Donner H., . . . Madhok S. (2004). Reproductive agency, medicine, and the state: Cultural transformations in childbearing. New York: Berghahn Books. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2012). Safe abortion: Technical and policy guidance for health systems (2nd ed.). Geneva, Switzerland: Author. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]