Abstract

Background:

Postoperative rehabilitation after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair (ARCR) remains controversial and suffers from limited high-quality evidence. Therefore, appropriate use criteria must partially depend on expert opinion.

Hypothesis/Purpose:

The purpose of the study was to determine and report on the standard and modified rehabilitation protocols after ARCR used by member orthopaedic surgeons of the American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine (AOSSM) and the Arthroscopy Association of North America (AANA). We hypothesized that there will exist a high degree of variability among rehabilitation protocols. We also predict that surgeons will be prescribing accelerated rehabilitation.

Study Design:

Cross-sectional study; Level of evidence, 4.

Methods:

A 29-question survey in English language was sent to all 3106 associate and active members of the AOSSM and the AANA. The questionnaire consisted of 4 categories: standard postoperative protocol, modification to postoperative rehabilitation, operative technique, and surgeon demographic data. Via email, the survey was sent on September 4, 2013.

Results:

The average response rate per question was 22.7%, representing an average of 704 total responses per question. The most common immobilization device was an abduction pillow sling with the arm in neutral or slight internal rotation (70%). Surgeons tended toward later unrestricted passive shoulder range of motion at 6 to 7 weeks (35%). Strengthening exercises were most commonly prescribed between 6 weeks and 3 months (56%). Unrestricted return to activities was most commonly allowed at 5 to 6 months. The majority of the respondents agreed that they would change their protocol based on differences expressed in this survey.

Conclusion:

There is tremendous variability in postoperative rehabilitation protocols after ARCR. Five of 10 questions regarding standard rehabilitation reached a consensus statement. Contrary to our hypothesis, there was a trend toward later mobilization.

Keywords: general, shoulder, rotator cuff, physical therapy/rehabilitation, arthroscopic, ARCR

Despite enormous interest in determining factors that would correlate with improved patient outcomes, satisfaction, and function after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair (ARCR), relatively little is known about the influence of postoperative rehabilitation protocols on tendon healing and functional outcome.5,14,18 Patient, surgeon, and physical therapist heterogeneity contribute to the difficulty in developing clinical practice guidelines for rehabilitation after ARCR. As such, surgeons vary with regard to many aspects of rehabilitation after ARCR. Traditionally, arthroscopists have prescribed a short period of immobilization in a sling with the arm in neutral followed by early, passive range of motion (ROM) to minimize stiffness and avoid delays in return to shoulder function. However, the effect of tendon involvement pattern, type of mobilization device, position of immobilization, timing of shoulder motion, and influence of repair type on tendon healing remains largely unknown. Strengthening and full return to activities are also controversial.2,6–8,10,13 The current American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) Clinical Practice Guideline Summary cannot recommend for or against using an abduction pillow or specific type of sling.11 Also, no recommendation could be made for a specific time frame of complete shoulder immobilization, or the delay before starting active resistance exercises after ARCR. Finally, the AAOS could not recommend for or against home-based exercise programs versus facility-based rehabilitation after ARCR. Factors such as age, tobacco use, workers’ compensation, and repair quality may cause surgeons to deviate from their usual protocol. However, there is limited high-level evidence to guide alterations in standard protocols.1,7,9,10

Basic science research in animal models shows that mature healing of the supraspinatus tendon takes up to 4 months.16 Such models support the notion that early repair site micromotion may negatively affect tendon healing; however, some studies show benefit to early passive ROM.2,15 The benefits and risks of early shoulder motion compared with immobilization after ARCR have not been completely defined. New repair techniques such as the double-row repair are becoming increasingly popular for large tears. Type and quality of repair as well as concomitant pathology such as labral tears, subscapularis pathology, or biceps involvement may influence rehabilitation speed in an attempt to minimize stiffness while avoiding a dreaded rerupture.3,9,17 As a result of a paucity of high-quality evidence, expert consensus represents an important tool to guide rehabilitation after surgery. Primarily, we hypothesized that there will exist a high degree of variability among rehabilitation protocols. In addition, we predict that surgeons will be prescribing accelerated rehabilitation depending on repair type and tissue quality. The purpose of this study was to determine and report on the standard and modified rehabilitation protocols after ARCR used by member orthopaedic surgeons of the American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine (AOSSM) and the Arthroscopy Association of North America (AANA).

Methods

Questionnaire Development

A clinical question was asked whether variation exists among orthopaedic surgeons in their practice of postoperative rehabilitation after ARCR. After performing a computerized search of the PubMed database, the senior author (R.C.B.) generated and compiled a questionnaire based on a review of the literature. The 29-question survey in English language is outlined in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Study Questionnairea

|

aSurgeons were instructed to answer based upon their routine postoperative rehabilitation protocol after fully arthroscopic rotator cuff repair of a typical, medium-sized tear in a healthy patient with good tissue quality. AANA, Arthroscopy Association of North America; AOSSM, American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine.

The electronic questionnaire consisted of 4 categories: standard postoperative protocol, modification to postoperative rehabilitation, utilized operative technique, and surgeon demographic data. Each of the 4 categories contained different subdivisions and had multiple choice answering possibilities. The survey was created on the website SurveyMonkey (www.surveymonkey.com) and was sent to all associate and active members of the AANA and the AOSSM. Full, active surgeons from these 2 groups were chosen as an appropriate subject population because their members consist of physicians who demonstrate a continuing interest in arthroscopy and many are pioneers in the field who are responsible for developing new and more sophisticated procedures and instruments. The orthopaedic surgeons and their email addresses were generated through membership directories. Via email, the survey was sent on September 4, 2013 (round 1), and reminders were sent on September 18 (round 2) and October 24 (round 3). Three weeks after the final reminder email, the survey was closed. The data were collected through the SurveyMonkey web tool, and the responses were kept confidential. The surgeons were instructed to choose the single most appropriate response and allowed only 1 answer per question, unless otherwise noted. Additionally, surgeons were instructed to answer based on the assumption of a routine postoperative rehabilitation protocol after ARCR of a typical, medium-sized tear in a healthy patient with good tissue quality.

Statistical Analysis

The total number of responses for each question was tabulated. Standard descriptive statistics were organized using GraphPad Prism (Prism Software) and shown in percentages (ratio of respondents). Questions that reached 50% or greater agreement among respondents were considered to be consensus statements and are shown in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Summary of Questions That Reached Majority Consensus (>50% Agreement)a

| Question | Response | % Agreement |

|---|---|---|

| Immobilization | Abduction pillow sling | 70 |

| Start passive ROM | <2 wk | 69 |

| Start active ROM | 7-10 wk | 61 |

| Unrestricted active ROM | 7-10 wk | 53 |

| Strengthening | 6 wk to 3 mo | 56 |

aROM, range of motion.

Results

The survey was sent to 3292 email addresses. Seventy-five surgeons opted out of the survey and 111 requests failed due to incorrect email addresses. Removing these from the final analysis resulted in a total of 3106 potential arthroscopists. The average response rate per question was 22.7%, representing an average of 704 total responses per question (range, 20.7%-23.0%).

Postoperative Protocols

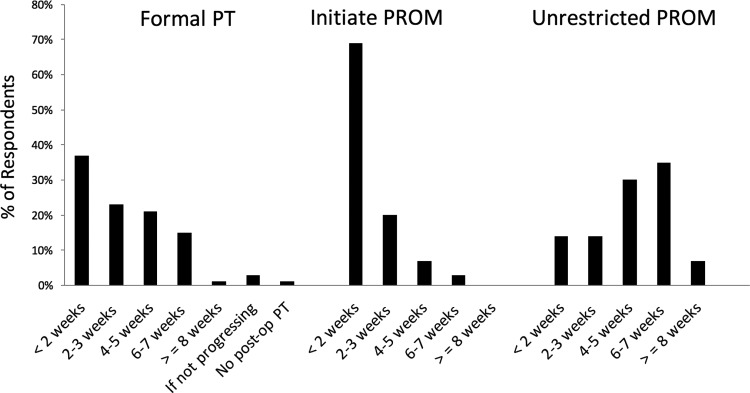

The most common immobilization device was an abduction pillow sling (arm in neutral or slight internal rotation) (70%). Position of immobilization nearly reached a majority consensus, with internal rotation being employed by 45% of surgeons. Formal physical therapy was most commonly initiated postoperatively within the first 2 weeks (37%) (Figure 1). The majority of respondents initiated passive shoulder ROM within the first 2 weeks (69%), followed by unrestricted passive shoulder ROM at 6 to 7 weeks (35%) as shown in the Appendix.

Figure 1.

Response data showing initial referral to physical therapy (PT) and passive range of motion (PROM) within the first 2 weeks after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Unrestricted PROM trended toward later time points, with the majority of surgeons waiting between 4 and 7 weeks postoperatively.

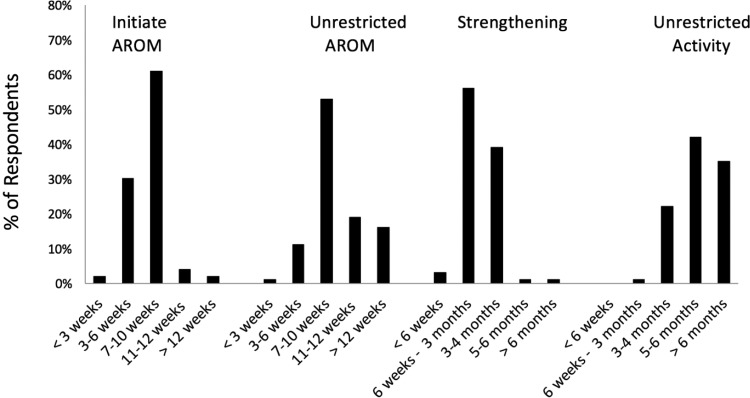

Active ROM was begun by most surgeons at 7 to 10 weeks (61%), with unrestricted active ROM being started at 7 to 10 weeks, with a consensus response of 53%. Strengthening (resistance) exercises were most commonly prescribed between 6 weeks and 3 months (56%). Unrestricted return to all activities was started at 5 to 6 months by nearly half of participants (42%), as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Initiation of active range of motion (AROM) was most commonly between 7 and 10 weeks. Strengthening was started shortly thereafter, between 6 weeks and 3 months. A trend toward later unrestricted return to activity was shown.

Protocol Alterations

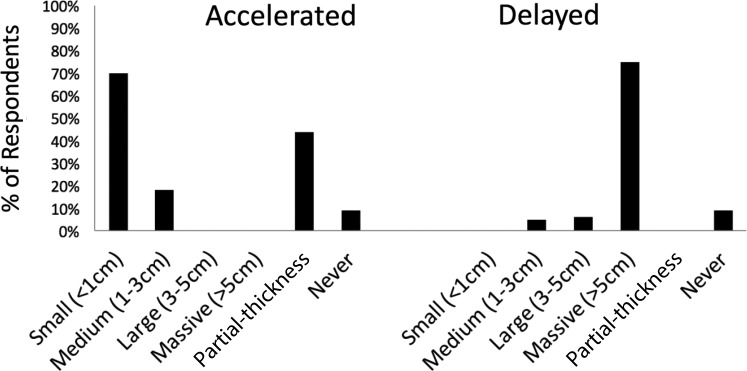

Protocols were altered most frequently based on tissue quality (85%) and involvement of the subscapularis (67%). Protocols were less frequently altered for concomitant procedures on the biceps tendon (35%), patient age (31%), and least commonly for workers’ compensation (WCB) status (3%). The majority of respondents also alter rehabilitation based on tear size (86%), with small tears (under 1 cm) most commonly prescribing quicker rehabilitation (89%). Partial-thickness tears were also prescribed accelerated rehabilitation by 55% of surgeons. A delayed protocol was prescribed for massive tears (over 5 cm) in the majority of respondents who decided to alter rehabilitation (75%), as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Seventy percent of surgeons prescribed an accelerated rehabilitation protocol for repairs performed on small (<1 cm) tears and 44% did the same for partial-thickness tears. Delayed rehabilitation protocols were employed by 75% of surgeons when repairing massive (>5 cm) rotator cuff tears.

Smoking status influenced rehabilitation for 30% of surgeons, and a small contingent (6%) responded that they do not perform rotator cuff repair on smokers.

Surgical Technique

Rotator cuff repairs were performed exclusively arthroscopically by greater than half (58%) of the respondents. The vast majority of surgeons (91%) indicated that they have performed double-row (including transosseous equivalent) repairs in their practice. Half of respondents (50%) perform the majority of their repairs using a double-row construct. However, only 5% of surgeons alter rehabilitation protocol in patients undergoing double-row repairs, most commonly using an accelerated passive ROM protocol (47%).

Surgeon Characteristics

More than half of the respondents (57%) performed greater than 50 fully arthroscopic rotator cuff repairs in the previous year. Thirty-seven percent of surgeons have been in practice for 20 or more years. The majority of surgeons described their practice as community-based, with only 14% being university-based. Thirty-four percent of respondents were exclusively members of the AANA, and 22% were exclusively members of the AOSSM. Nearly half belonged to both societies. Interestingly, the majority of the respondents (59%) agreed that they would change their protocol based on differences expressed in this survey.

Discussion

The most important finding of the study is that there is tremendous variability in postoperative rehabilitation protocols after all-arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Only 5 of 10 questions regarding standard rehabilitation reached consensus. The questions that did not reach consensus included preferred position of immobilization, when to initiate formal physical therapy, and timing of unrestricted passive ROM as well as unrestricted return to full activities. Clearly, additional research on these aspects is needed to form an appropriate use criteria statement. Variability in responses may in fact be a positive sign, as therapy should be individualized. The ideal postoperative physical therapy program is that which is best suited to the patient.

Timing of when to initiate passive and active ROM, as well as strategies to minimize stiffness, are unclear. For instance, Cuff et al2 randomized 68 patients with full-thickness crescent-shaped tears of the supraspinatus repaired using a transosseous-equivalent suture bridge technique along with subacromial decompression to receive passive mobilization on day 2 or starting after 6 weeks. They found no clinically significant difference at 1-year follow-up; however, tendon healing as assessed by ultrasound showed slightly better healing rates for patients with delayed passive mobilization. In another study, Koo et al9 identified 79 patients out of 152 undergoing primary ARCR with risk factors for stiffness identified in a previous study. Patients with calcific tendinitis, adhesive capsulitis, PASTA (partial articular surface tendon avulsion) repair, concomitant labral repair, or single-tendon cuff repair were started on early passive ROM on postoperative day 1. This comprised standard rehabilitation plus table slides for passive overhead motion. Using this protocol, no patients developed postoperative stiffness. This represented a significant difference from historical controls with the same risk factors (Fisher exact test, P < .004).

In a prior survey conducted by the senior author (R.C.B.), 74% of surgeons were starting early ROM (unpublished data, 2010). The present study revealed a slight trend away from this practice as only 69% of surgeons were starting passive ROM within 2 weeks. A similar trend toward later active ROM was noted. Previous studies suggest that early motion puts the repaired tendon at increased risk for retear. A minority of the respondents in our study (10%) waited 4 weeks or longer to mobilize a medium-sized tear in a healthy patient. Gradual strengthening exercises are typically employed; however, the exact timeline also remains controversial. Koo et al9 started strengthening at 3 months, citing a primate study that showed a conservative protocol allows Sharpey fibers to form before stressing the repair with resistive exercises. This was in agreement with the most popular answer in this study, which was to start strengthening between 6 weeks and 3 months. Similarly, Jung et al4 devised a 4-phase rehabilitation protocol by performing a literature review and surveying 63 surgeons from the German Society of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery (DVSE). Their group recommended strengthening at 3 months after surgery.

A number of studies using animal models have examined the use of passive motion versus immobilization. The most extensively used model for examining tendon healing is in rats. Peltz et al12 found slightly decreased ROM in a rat model with early passive motion compared with immobilization for 6 weeks. They speculated that early motion may increase scar formation and decrease ROM. In a similar study performing supraspinatus repairs in healthy rats, the authors found that immobilized repairs had “markedly higher collagen orientation, more nearly normal extracellular matrix genes, and increased quasilinear viscoelastic properties than did the tendons from subjects that were exercised.”16 However, the only animal model that possesses the unique orthogonal orientation of muscle fibers in the supraspinatous tendon is in higher level primates. Using a primate model, Sonnabend et al15 showed immature healing at 4 weeks and tendon remodeling by 8 weeks. The animals received neither immobilization device nor formal physiotherapy program.

Tear characteristics, type and quality of repair, and patient comorbidities like diabetes, smoking, and workers’ compensation claim may influence rehabilitation speed. In our study, 86% of surgeons alter rehabilitation based on tear size, 87% based on tissue quality, and 67% if there is involvement of the subscapularis tendon. A small subset (6%) of surgeons responded that they would refuse to operate on a patient who is a smoker. A recent systematic review published in Arthroscopy 1 revealed that smoking is associated with rotator cuff tears, shoulder dysfunction, and shoulder symptoms. Smoking may also accelerate rotator cuff degeneration, lead to decreased healing rates, and increase the prevalence of larger rotator cuff tears.1 The authors concluded that smoking may increase the prevalence of symptomatic rotator cuff disease and therefore influence a greater number of patients to seek surgical intervention. A recent meta-analysis by Xu et al18 revealed a lower retear rate and higher American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) scores for double-row repairs; however, it remains unclear how new repair techniques should affect postoperative protocols. At the time of our survey, the vast majority (95.2%) of surgeons did not alter their postoperative rehabilitation after double-row ARCR.

Limitations

Several limitations of this study must be considered. The relatively low response rate (23%) is a weakness; however, the overall number of responses (704) was high, and most surgeons were classed as experienced arthroscopists. Another limitation of this study is the scope of questions. We did not address specific motions such as internal rotation stretching and strengthening or return to sport. Additional factors that may influence rehabilitation speed that were not specifically addressed include copathologies such as calcific tendinitis, adhesive capsulitis, PASTA, and concomitant labral repairs. Finally, surgeons may be unaware of what exercises a patient has been informed to do by their physical therapist. Future studies may more accurately assess rehabilitation protocols by acquiring the printed guidelines that the surgeons distribute to their patients. Surveys and observational studies have limited ability to yield meaningful, generalizable conclusions. However, they are appropriate for characterizing areas of controversy as well as aiding to develop appropriate use criteria in the absence of high-level randomized controlled trials. Future research is needed to directly compare immobilization type, position, and factors influencing rehabilitation speed.

Conclusion

We report on the largest survey to date of rehabilitation protocols after ARCR according to the most qualified arthroscopists in North America. Several responses reached a consensus of more than 50% agreement. These included immobilization in an abduction pillow sling with the arm in neutral or slight internal rotation, passive ROM within 2 weeks postoperatively, active ROM at 7 to 10 weeks, and strengthening between 6 and 12 weeks.

Appendix

Responses to Postoperative Rehabilitation and Preference Questions

Surgeons were instructed to answer based on routine postoperative rehabilitation protocol after fully arthroscopic rotator cuff (RC) repair of a typical, medium-sized tear in a healthy patient with good tissue quality.

|

Footnotes

The authors declared that they have no conflicts of interest in the authorship and publication of this contribution.

Ethical approval for this study was waived by the University of Saskatchewan Research Ethics Board.

Presented as a poster at the Canadian Orthopedic Residents Association 2014 Annual Meeting, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, June 2014.

References

- 1. Bishop YJ, Santiago-Torres JE, Rimmke N, Flanigan DC. Smoking predisposes to rotator cuff pathology and shoulder dysfunction: a systematic review. Arthroscopy. 2015;31:1598–1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cuff DJ, Pupello DR. Prospective randomized study of arthroscopic rotator cuff repair using an early versus delayed postoperative physical therapy protocol. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21:1450–1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Denard PJ, Jiwani AZ, Ladermann A, Burkhart SS. Long-term outcome of arthroscopic massive rotator cuff repair: the importance of double-row fixation. Arthroscopy. 2012;28:909–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jung C, Tepohl L, Tholen R, et al. Rehabilitation after rotator cuff repair. Obere Extremität. 2016;11:16–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Keener JD, Galatz LM, Stobbs-Cucchi G, Patton R, Yamaguchi K. Rehabilitation following arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: a prospective randomized trial of immobilization compared with early motion. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96:11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kim YS, Chung SW, Kim JY, Ok JH, Park I, Oh JH. Is early passive motion exercise necessary after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair? Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:815–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kluczynski MA, Nayyar S, Marzo JM, Bisson LJ. Early versus delayed passive range of motion after rotator cuff repair: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:2057–2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Koh KH, Lim TK, Shon MS, Park YE, Lee SW, Yoo JC. Effect of immobilization without passive exercise after rotator cuff repair: randomized clinical trial comparing four and eight weeks of immobilization. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96:441–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Koo SS, Parsley BK, Burkhart SS, Schoolfield JD. Reduction of postoperative stiffness after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: results of a customized physical therapy regimen based on risk factors for stiffness. Arthroscopy. 2011;27:155–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lee BG, Cho NS, Rhee YG. Effect of two rehabilitation protocols on range of motion and healing rates after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: aggressive versus limited early passive exercises. Arthroscopy. 2012;28:34–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pedowitz RA, Yamaguchi K, Ahmad CS. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Clinical Practice Guideline on: optimizing the management of rotator cuff problems. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94:163–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Peltz C, Dourte LM, Kuntz AF. The effect of postoperative passive motion on rotator cuff healing in a rat model. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:2421–2429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Riboh JC, Garrigues GE. Early passive motion versus immobilization after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Arthroscopy. 2014;30:997–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Slabaugh MA, Nho SJ, Grumet RC, et al. Does the literature confirm superior clinical results in radiographically healed rotator cuffs after rotator cuff repair? Arthroscopy. 2010;26:393–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sonnabend DH, Howlett CR, Young AA. Histological repair of the rotator cuff in a primate model. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92:586–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Thomopolous S, Williams GR, Soslowsky LJ. Tendon to bone healing: differences in biomechanical, structural, and compositional properties due to a range of activity levels. J Biomech Eng. 2003;125:106–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Warrender WJ, Brown OL, Abboud JA. Outcomes of arthroscopic rotator cuff repairs in obese patients. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20:961–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Xu C, Zhao J, Li D. Meta-analysis comparing single-row and double-row repair techniques in the arthroscopic treatment of rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23:182–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]