Abstract

Objective:

The first national survey to assess the prevalence of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) in Canada was the 2012 Canadian Community Health Survey: Mental Health and Well-Being (CCHS-MH). The World Mental Health Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WMH-CIDI), used within the representative sample of the CCHS-MH, provides the best available description of the epidemiology of this condition in Canada. This study uses the CCHS-MH data to describe the epidemiology of GAD.

Method:

The analysis estimated proportions and odds ratios and used logistic regression modelling. All results entailed appropriate sampling weights and bootstrap variance estimation procedures.

Results:

The lifetime prevalence of GAD is 8.7% (95% CI, 8.2% to 9.3%), and the 12-month prevalence is 2.6% (95% CI, 2.3% to 2.8%). GAD is significantly associated with being female (OR 1.6; 95% CI, 1.3 to 2.1); being middle-aged (age 35-54 years) (OR 1.6; 95% CI, 1.0 to 2.7); being single, widowed, or divorced (OR 1.9; 95% CI, 1.4 to 2.6); being unemployed (OR 1.9; 95% CI, 1.5 to 2.5); having a low household income (<$30 000) (OR 3.2; 95% CI, 2.3 to 4.5); and being born in Canada (OR 2.0; 95% CI, 1.4 to 2.8).

Conclusions:

The prevalence of GAD was slightly higher than international estimates, with similar associated demographic variables. As expected, GAD was highly comorbid with other psychiatric conditions but also with indicators of pain, stress, stigma, and health care utilization. Independent of comorbid conditions, GAD showed a significant degree of impact on both the individual and society. Our results show that GAD is a common mental disorder within Canada, and it deserves significant attention in health care planning and programs.

Keywords: generalized anxiety disorder, epidemiology, anxiety, population studies, cross-sectional studies, major depressive disorder

Abstract

Objectif:

La première enquête nationale qui a évalué la prévalence du trouble d’anxiété généralisée (TAG) au Canada a été l’Enquête sur la santé dans les collectivités canadiennes – Santé mentale (ESCC – SM) de 2012. L’entrevue WMH-CIDI, utilisée dans l’échantillon représentatif de l’ESCC – SM, offre la meilleure description disponible de l’épidémiologie de cette affection au Canada. Cette étude décrit l’épidémiologie du TAG à l’aide des données de l’ESCC – SM.

Méthode:

L’analyse a estimé les proportions, les rapports de cotes, et utilisé les modèles de régression logistique. Tous les résultats produits utilisaient les procédures de poids d’échantillonnage appropriées et d’estimation de variance bootstrap.

Résultats:

La prévalence du TAG de durée de vie est de 8,7% (IC à 95% 8,2 à 9,3), et la prévalence de 12 mois est de 2,6% (IC à 95% 2,3 à 2,8). Le TAG est significativement associé au fait d’être femme (RC 1,6; IC à 95% 1,3 à 2,1), d’âge moyen (âge 35-54; RC 1,6; IC à 95% 1,0 à 2,7), célibataire, veuf ou divorcé (RC 1,9; IC à 95% 1,4 à 2,6), sans emploi (RC 1,9; IC à 95% 1,5 à 2,5), d’avoir un faible revenu du ménage (< 30 000 $) (RC 3,2; IC à 95% 2,3 à 4,5) et d’être né au Canada (RC 2,0; IC à 95% 1,4 à 2,8).

Conclusions:

La prévalence du TAG était légèrement plus élevée que les estimations internationales, avec des variables démographiques associées semblables. Comme prévu, le TAG était très comorbide avec d’autres affections psychiatriques, mais aussi avec des indicateurs de douleur, de stress, de stigmates et d’utilisation des soins de santé. Indépendamment des affections comorbides, le TAG révélait un degré significatif d’impact sur la personne et la société. Nos résultats indiquent que le TAG est un trouble mental commun au Canada, et qu’il mérite une attention significative dans la planification et les programmes de soins de santé.

Anxiety disorders are a pervasive problem and account for approximately 2% of health-related disability in Canada.1 Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) is recognized as the most common anxiety disorder within primary care, carrying a significant degree of comorbidity, impairment, and disability.2 GAD is characterized by a chronic, persistent pattern of worrying, anxiety symptoms, and tension that has a waxing and waning course often without full remission.3 Estimates indicate that 2.4 million Canadians will report symptoms consistent with a diagnosis of GAD in their lifetime.4

The descriptive epidemiology of GAD has lagged because of the shifting Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) nosology and concerns regarding the independence of GAD as its own unique disorder.5 In addition, basic Canadian epidemiological data are limited in national estimates, and inconsistencies are seen in research methods applied in provincial and regional surveys.6 This has left a major gap in our understanding of GAD across Canada.

The 2012 Canadian Community Health Survey, Mental Health (CCHS-MH) used the World Mental Health (WMH) version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) to provide the first ever description of the epidemiology of GAD in the national population. The large, representative sample of the CCHS-MH allows description of the patterns of distribution of GAD within Canada. To date, only 2 studies have used the CCHS-MH 2012 data in relation to GAD. Pearson et al.4 examined the basic epidemiology of 6 major disorders described in the CCHS-MH. Their study showed that the lifetime prevalence of GAD was 8.7%, that higher rates were seen in females, that GAD was frequently seen with comorbid depressive disorders, and that GAD had a somewhat stable prevalence across the age spectrum. Sunderland and Findlay7 investigated perceived need for mental health services by using the CCHS-MH 2012 data. The investigators found that individuals reporting a mood or anxiety disorder had significantly higher odds of perceiving a mental health need (information, counselling, medication) compared with individuals without a mental disorder.

This study provides further investigation into the descriptive epidemiology of GAD, extending the results of the earlier studies by Pearson et al.4 and Sunderland and Findlay.7 Sunderland and Findlay7 demonstrated that there is a significant, unmet health care need for mental health conditions in Canada. This study reviews further the impact of GAD alone compared with substance use and mood disorders. This greater understanding of the epidemiology of GAD is necessary to inform future health care decisions and generate hypotheses for prevention strategies in the Canadian population.

Methods

The 2012 CCHS-MH is designed to provide a comprehensive analysis of mental health in Canadians. The initial sample design included 43 000 dwellings, based on individuals over the age of 15 in geographical clusters across Canada.8 From the initial raw sample, 36 443 dwellings were found to be in scope of the survey, and 79.8% of these households (29 088) agreed to participate.8 A final individual sample of 25 113 was obtained, resulting in an individual response rate of 86.3% and an overall response rate of 68.9%.8 Interviews were performed across Canada between January 2012 and December 2012 using computer-assisted personal interviewing.8 Approximately 87% of interviews were performed in person.8 Roughly 3% of the population was excluded from the survey’s sampling frame, including individuals living on reserves and other Aboriginal settlements, full-time members of the Canadian Forces, and the institutionalized population.8

Sampling weights were produced by Statistics Canada to ensure that the survey estimates are representative of the Canadian household population.8 Each participant was given a survey weight, so that his or her responses represent a certain number of people in the entire population.8 This weight is based on several factors but includes adjustments for nonresponse at the household and personal level; it also accounts for extreme values, unequal selection probabilities, and exclusion of out-of-scope units.8 Five hundred replicate bootstrap weights are applied to all output data to create accurate confidence intervals and account for clustering in the multistage sampling procedure.8

Various versions of the CIDI have been the mainstay of community-based studies in psychiatric epidemiology during the past 2 decades. A version of the CIDI developed for the WMH Survey program, the WMH-CIDI incorporated many improvements over earlier versions,9 especially the use of cognitive interviewing techniques. Reappraisal in relation to Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) interviews could not specifically examine GAD but found that 83.7% of past-year anxiety disorders were identified by this version of the CIDI.10

The standardized interview consists of multiple different modules that can be used for analysis. The WMH-CIDI modules used DSM-IV criteria to estimate lifetime and 12-month prevalence of psychiatric disorders. Diagnoses included GAD, major depressive disorder (MDD), bipolar disorder (BD), alcohol abuse, alcohol dependence, drug abuse, and drug dependence.9 The module for each psychiatric disorder was determined through the standardized questions and identified using a diagnostic algorithm to determine who met criteria for each disorder.7 Demographic indicators assessed in the survey included gender, age, marital status, level of education, employment, immigrant status, and urban living, all which were determined by standardized interview questions.8 Household income was determined by income decile brackets.

As GAD is a highly comorbid condition, the impact of GAD was determined by separating GAD from 12-month prevalence of mood and substance use disorders (MSUDs). A substance use disorder was considered to be a diagnosis of alcohol or drug dependence or alcohol or drug abuse, as based on DSM-IV criteria. Mood disorders encompassed both bipolar disorder and MDD. Adjusted odds ratios were then reported based on the presence of GAD alone, MSUDs alone, or both GAD and MSUDs. These 3 categories were then analyzed in respect to areas of impact, including work and income, self-perceived interference with life, health care utilization, and suicide. These different areas were evaluated through self-reported health scales, health care utilization modules, and suicide modules. To assess pain, items used to classify pain-specific health states for the Health Utility Index10 were used. These items identify respondents with a “usual” experience of pain sufficient to interfere with their day-to-day activities. The remainder of CCHS measures consisted of field-tested, but not formally validated, survey items and modules. Interference with life was determined by multiple scales and items to assess self-perceived health, stress, and pain. Stigma was assessed using a module developed through collaboration between the Mental Health Commission of Canada and Statistics Canada and administered to participants who had received treatment within the last year.11 Health care utilization was assessed by a module developed by Statistics Canada to determine professional consultation and hospitalization.8 Suicide was assessed in a module by Statistics Canada that addressed 12-month and lifetime prevalence of thoughts, plans, and attempts.8 The survey also assessed work absenteeism in the last week and income strain, based on respondent-reported difficulty meeting basic household expenses.8

Data analysis used Stata version 12.8 at the Statistics Canada Prairie Regional Data Centre. Descriptive techniques were used for the cross-sectional data, including estimation of frequencies and odds ratios. Logistic regression modeling was used to produce adjusted estimates and to help describe a smoothed pattern of age-specific prevalence by incorporating age as a continuous variable. Past-year rather than lifetime GAD prevalence was the primary focus of the analysis, as there are concerns regarding the validity of lifetime prevalence.12

Results

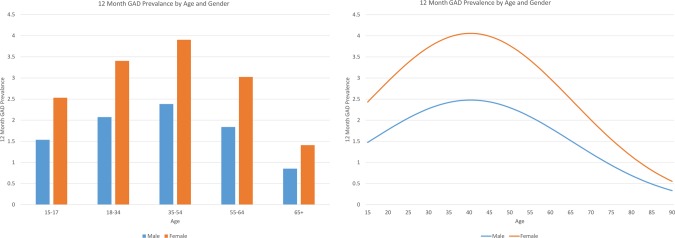

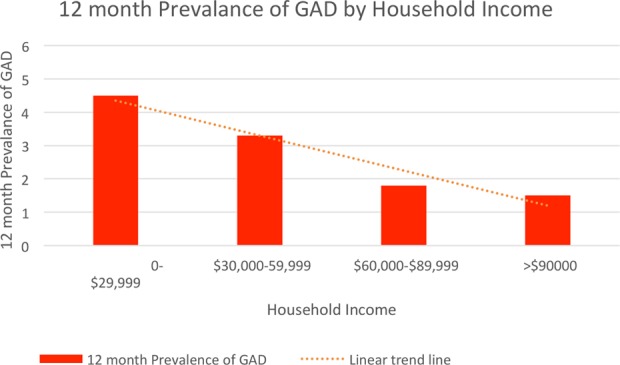

Demographic characteristics of the CCHS-MH sample population in association with 12-month prevalence of GAD are shown in the Appendix, Supplementary Table 1. Results showed a 8.7% (95% CI, 8.2% to 9.3%) lifetime prevalence of GAD, a 2.6% (95% CI, 2.3% to 2.8%) 12-month prevalence of GAD, and a 1.6% (95% CI, 1.3% to 1.8%) 30-day prevalence of GAD. The 12-month prevalence of GAD amongst women was 3.2% (95% CI, 2.7 to 3.6), whereas the prevalence amongst men was 2.0% (95% CI, 1.6% to 2.3%). An unadjusted odds ratio (OR) of 1.6 (95% CI, 1.3 to 2.1) indicated a significantly higher annual prevalence of GAD in women. Widowed, separated, and divorced individuals also had a higher prevalence, relative to married respondents: 3.8% (95% CI, 2.9% to 4.7%), which was associated with an unadjusted OR of 1.9 (95% CI, 1.4 to 2.6). Level of education (unadjusted OR for secondary level graduation or less, 1.1; 95% CI, 0.9 to 1.5) and urban living (unadjusted OR 1.0; 95% CI, 0.8 to 1.4) were not significantly associated with GAD. Subjects who were not working in the last week had 1.9 times higher odds (95% CI, 1.5 to 2.5) of GAD in comparison to those with full-time work. Last, subjects born in Canada were 2.0 times (95% CI, 1.4 to 2.8) more likely to experience GAD when compared with immigrants. Figure 1 presents age-specific prevalence from a model including age and age squared, providing a smoothed nonlinear description of annual prevalence as a function of age. Figure 2 shows the relation between household income and GAD, demonstrating the trend of higher rates of GAD amongst those with lower incomes.

Figure 1.

Past year generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) prevalence by age and gender.

Figure 2.

Past year generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) prevalence by household income.

A logistic regression was performed to further analyze the demographic indicators with 12-month prevalence of GAD. The analysis included the same variables included in Supplementary Table 1. Variables found to be significant included sex, age, age squared, marital status, Canadian birth, part-time work and unemployment, and low household income (<$29 999 and $30 000-$59 999). The results of this multivariable analysis resembled the unadjusted estimates, except that an effect of marital status was no longer evident, the associations with alcohol use disorders weakened, and those for cannabis and drug use disorders were no longer significant. The adjusted estimates are available in the Appendix (Supplementary Table 2) for further review.

Further analysis was performed to estimate the impact of GAD alone, MSUD alone, or both GAD and an MSUD, when compared with a baseline group with no disorders. These analyses were undertaken in order to discern the extent to which the impact of GAD was due to comorbidity with other conditions. Table 1 shows the adjusted odd ratios of each indicator controlled for age, age squared, and gender that were found to be significant in our logistic regression analysis (see Supplementary Table 2). The adjusted odds ratio for the effect of GAD alone on perceived life stress was 3.5 (95% CI, 2.4-5.1), whereas MSUD alone had an adjusted odds ratio of 2.4 (95% CI, 2.0-2.8). When both conditions were combined there was an adjusted odds ratio of 7.9 (95% CI, 5.8-10.6), significantly higher than each alone and roughly equal to the product of their 2 effects. For many variables the joint effect was less than multiplicative (Table 1). Analysis showed that 12-month suicide thoughts and plans or attempts were more strongly associated with MSUDs without GAD than with GAD without comorbidity. When an individual had both, his or her odd ratios were again significantly higher than when individually reported (Table 1). The finding of substantially higher impact in those with comorbid conditions was not seen for some other variables, such as household income and perceived stigma.

Table 1.

Workplace and economic impact, interference with life, health care utilization, and suicide indicator analysis with generalized anxiety disorder, mood or substance use disorders, or botha.

| GAD yes, MSUDs no | GAD no, MSUDs yes | GAD yes, MSUDs yes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Workplace and economic impact | |||

| Work absentee—last week | 1.9 (1.1-3.4) | 1.6 (1.1-2.4) | 1.9 (1.0-3.5) |

| Current household income—difficulty meeting basic expenses | 3.3 (2.2-4.8) | 2.5 (2.0-3.1) | 6.6 (4.7-9.2) |

| Interference with life | |||

| Self-perceived health in general | 5.4 (3.7-8.0) | 3.5 (2.8-4.2) | 13.4 (9.9-18.0) |

| Self-perceived life stress | 3.5 (2.4-5.1) | 2.4 (2.0-2.8) | 7.9 (5.8-10.6) |

| Pain and discomfort—HUI function code | 5.1 (3.5-7.4) | 3.1 (2.5-3.7) | 8.8 (6.3-12.2) |

| Perceived prejudice or discrimination regarding mental health | 1.6 (0.9-2.9) | 2.7 (1.8-4.1) | 2.8 (1.8-4.5) |

| Health care utilization | |||

| Consultation with professional services—past 12 months | 16.9 (11.9-24.0) | 8.8 (7.3-10.6) | 29.4 (20.5-42.1) |

| Hospitalized overnightb | 8.1 (2.7-24.7) | 12.8 (7.3-22.3) | 33.9 (17.6-65.1) |

| Suicide | |||

| Suicide thoughts—past 12 months | 10.0 (6.1-16.6) | 11.2 (8.6-14.7) | 28.4 (20.0-40.4) |

| Suicide plan or attempt—past 12 months | 11.5 (4.3-30.5) | 22.4 (13.2-38.0) | 61.6 (34.4-110.3) |

GAD = generalized anxiety disorder; HUI = health utility index; MSUDs = mood and substance use disorders.

aValues are expressed as odds ratios (adjusted for sex, age, and age squared) and 95% confidence intervals. N = 24 861 for all data.

bAt least overnight in the preceding 12 months for reasons of mental health, alcohol, or drugs.

In respect to health care utilization, individuals who seek professional support were more likely to have GAD in the absence of MSUD rather than MSUD in the absence of GAD. However, consistent with expectation, hospitalization was more strongly associated with MSUD (in the absence of GAD) than with GAD (in the absence of MSUD). However, the greatest elevation in the risk/odds of hospitalization was seen in respondents with comorbid GAD and MSUD, suggesting that this comorbidity may be an indicator of the severity of respondents’ mental health difficulties (Table 1).

Discussion

Somers et al.13 produced a systematic review of prevalence and incidence rates of anxiety disorders globally. It was found that lifetime prevalence of GAD ranged from 1.9% in Basel, Switzerland, to 31.1% in Christchurch, New Zealand.10 The 12-month prevalence of GAD ranged from 0.15% in Northern Ireland to 12.7% in Christchurch, New Zealand.13 Our results (lifetime prevalence of GAD at 8.7% and 12-month prevalence of GAD of 2.6%) are slightly above estimates from the United States, New Zealand (a different estimate than the one from Christchurch), and Australia. The lifetime prevalence of GAD ranges from 5.7% in the United States to 6.1% in Australia.14 The 12-month prevalence of GAD in these countries ranges from 1.9% (New Zealand) to 3.1% (United States), consistent with our estimates.14 The very high prevalence in the Christchurch estimate contrasts with the lower prevalence estimates reported in a more recent Australian review.14 This variability can potentially be accounted for by vulnerabilities in measurement or other aspects of study design. The Canadian estimates are based on an adaptation of the WMH-CIDI, as is the estimate provided by the Australian researchers.14 The wide range of estimates in the review by Somers et al.13 resulted from the use of both clinician and diagnostic tools for GAD estimates. The Canadian prevalence estimates from the CCHS-MH seem to be at the high end of the range of international estimates.

The demographic indicators found in our study population are in keeping with international studies, including being female, being out of the labour force, being divorced or widowed, and being in the middle age ranges.2,14 Some studies have found that young women have the highest risk for GAD.15 European data, similar to our data, suggest that GAD is a relatively rare condition before the age of 20, with the majority of onsets being amongst older females.3 In addition, a difference was noted between lifetime and 12-month prevalence rates of GAD. This suggests that GAD potentially has a more episodic course or a higher rate of remission than is usually assumed. These demographic factors suggest that in Canada, GAD is most common amongst middle-aged women.

Immigrant status was protective for GAD in our Canadian data, in keeping with similar results found in Australia.14 Because our data are cross-sectional in nature, it is difficult to state whether this finding is related to a healthy immigrant effect, reflects true differences related to immigrant status, or results from cultural differences in mental health presentations or measurement. Low household incomes have been found to be associated with anxiety disorders and GAD specifically.15 The etiological implications of this association are difficult to decipher from cross-sectional data, as GAD could lead to lower income from decreased work productivity, or poverty itself may be a predisposing factor.15

As expected, GAD was found to be highly comorbid with multiple psychiatric conditions including MDD, alcohol abuse or dependence, and bipolar disorder. The lifetime comorbidity rates of psychiatric conditions within GAD are estimated to be above 90%, and our findings are in keeping with this.3 This rate of high comorbidity has historically supported the view that GAD is a prodromal, residual, or severity marker of other psychiatric conditions.5 Although GAD does have a significant rate of comorbidity, data now suggest that it is its own unique condition and needs to be looked at independently.5 Wittchen et al.16 showed that high comorbidity was a predictor of GAD in patients who sought medical treatment. Wittchen et al. believed that this created a bias in sample selection, artificially changing data on comorbidities. However, this would not affect our results since the CCHS-MH method did not depend on health care use. Additionally, the definition of GAD has changed over several iterations of the DSM, but it is recognized now that GAD has its own distinct symptom cluster apart from MDD.5 Last, it has been argued that the clinical course, sociodemographic predictors, and impairments related to GAD are unique when compared with comorbid conditions, suggesting that GAD should be studied as its own condition.5

In our study, we found that GAD carried significant impairment, independent of MSUDs. Our results suggest that individuals with GAD in the absence of these comorbidities experience a significant amount of stress and pain and have poorly perceived health. They are also significantly more likely to have difficulty attending work and making ends meet at home. Stigma and discrimination are also experienced by those with GAD. It is found that across multiple studies, GAD alone leads to disability and decreased work productivity equal to or greater than the burden caused by depression.2

Last, GAD is a common presentation amongst primary care and emergencies, leading to significant health care utilization and costs. This was seen in our results, as individuals who consulted professional support were more likely to have GAD alone when compared with MSUDs. When an individual had both diagnoses, these rates were dramatically increased. Unfortunately, GAD has relatively low rates of recognition and treatment amongst primary care practices.3 This suggests that interventions should be aimed at improving the recognition and treatment of GAD. Early recognition could halt the onset of significant impairments and comorbidities and possibly stop future relapses.3

Our study has several limitations. First, the CCHS-MH is a cross-sectional survey, and so no causality can be implied in our results. The assessment is performed by nonclinicians and thus does not have the rigor seen in a detailed clinical assessment. Although GAD was included in the 2012 CCHS-MH World Health Organization CIDI module, limited coverage of other anxiety disorders is provided. As such, our efforts to isolate the effects of GAD from those of MSUD were limited by an inability to assess all possible comorbidities. Many of the diagnostic categories assessed in the CCHS-MH were based on self-report and may be subject to inaccuracy.

Conclusion

Historically, GAD has been conceptualized as a highly comorbid condition, with little understanding regarding its impact on the individual and society. Our results demonstrate that GAD is a highly prevalent condition that carries a significant burden of disease. In Canada, individuals with GAD experience significant pain, stress, stigma, and discrimination and use significant health care resources, particularly in the outpatient setting. Therefore, it is imperative that future health care strategies and research take into consideration the burden of GAD in the Canadian population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The estimates reported in this article are derived from data collected by Statistics Canada, but the analysis and results are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not reflect the views of Statistics Canada. This work was approved by the University of Calgary Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) declared receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by a grant from the Calgary Health Trust and the University of Calgary Department of Psychiatry.

Supplemental Material: Supplementary material is available online with this article.

References

- 1. Global Burden of Disease. Seattle, WA: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation; 2015. [Accessed 8 April 2016]. Available at: http://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/ [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wittchen HU. Generalized anxiety disorder: prevalence, burden, and cost to society. Depress Anxiety. 2002;16(4):162–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lieb R, Becker E, Altamura C. The epidemiology of generalized anxiety disorder in Europe. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005;15(4):445–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pearson C, Janz T, Ali J. Mental and substance use disorders in Canada. Health at a Glance. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 82-624-X. Ottawa (ON): Statistics Canada; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kessler RC, Keller MB, Wittchen H-U. The epidemiology of generalized anxiety disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2001;24(1):19–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Patten SB, Williams JV, Lavorato DH, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of major depressive disorder in Canada in 2012. Can J Psychiatry. 2015;60(1):23–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sunderland A, Findlay LC. Perceived need for mental health care in Canada: results from the 2012 Canadian community health survey-mental health. Health Reports 82-003-x Ottawa (ON): Statistics Canada; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Canadian community health survey – mental health. Ottawa (ON): Statistics Canada; 2013. [Accessed 8 April 2016]. Available at: http://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&SDDS=5015#a2 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kessler RC, Üstün TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) survey initiative version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13(2):93–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Haro JM, Arbabzadeh-Bouchez C, Brugha TS, et al. Concordance of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview version 3.0 (CIDI 3.0) with standardized clinical assessments in the WHO World Mental Health surveys. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2006;15(4):167–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stuart H, Patten SB, Koller M, et al. Stigma in Canada: results from a rapid response survey. Can J Psychiatry. 2014;59(10 Suppl 1):S27–S33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Streiner DL, Patten SB, Anthony JC, et al. Has “lifetime prevalence” reached the end of its life? An examination of the concept. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2009;18(4):221–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Somers JM, Goldner EM, Waraich P, et al. Prevalence and incidence studies of anxiety disorders: a systematic review of the literature. Can J Psychiatry. 2006;51(2):100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McEvoy PM, Grove R, Slade T. Epidemiology of anxiety disorders in the Australian general population: findings of the 2007 Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2011;45(11):957–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Leray E, Camara A, Drapier D, et al. Prevalence, characteristics and comorbidities of anxiety disorders in France: results from the “Mental Health in General Population” survey (MHGP). Eur Psychiatry. 2011;26(6):339–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wittchen H-U, Zhao S, Kessler RC, et al. DSM 3-R generalized anxiety disorder in the national comorbidity survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:355–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.