Abstract

Objective:

The objective of this study was to evaluate the changes in demographic, geographic, and practice characteristics of all Ontario psychiatrists between 2003 and 2013 and their implication for access to psychiatrists.

Methods:

We included all psychiatrists who were clinically active in Ontario in any year from 2003 to 2013. For each psychiatrist, we reported age, sex, years since medical school graduation, geographic practice region, and practice characteristics such as total number of inpatients, outpatients, and outpatient visit frequencies.

Results:

In 2013, there were 2070 psychiatrists, with nearly half (47%) more than 30 years since medical school graduation. Female psychiatrists comprised 41% of all psychiatrists in 2013 but 56% of all psychiatrists within 15 years of medical school graduation. Between 2003 and 2013, there was a 17% increase in the total number of psychiatrists, with the largest growth in psychiatrists occurring in the group more than 30 years from medical school graduation. Over these 11 years, the mean (SD) number of unique outpatients seen by a psychiatrist annually increased from 208 (228) to 249 (275) (19.5%; P = 0.001), with male psychiatrists, on average, seeing more outpatients annually than female psychiatrists.

Conclusion:

The number of outpatients seen by psychiatrists is slowly increasing. However, the large proportion of aging psychiatrists, the high concentration of psychiatrists in urban settings, and the increase in the number of female psychiatrists with smaller practices suggest that without radical changes to the way psychiatrists practice, access to psychiatrists will remain a challenge in Ontario.

Keywords: healthcare policy, health services research, mental health services

Abstract

Objectif:

L’objectif de cette étude était d’évaluer les changements des caractéristiques démographiques, géographiques et de la pratique de tous les psychiatres de l’Ontario entre 2003 et 2013, et l’implication de ces changements pour l’accès aux psychiatres.

Méthodes:

Nous avons inclus tous les psychiatres qui étaient cliniquement actifs en Ontario pour toute année entre 2003 et 2013. Pour chaque psychiatre, nous avons indiqué l’âge, le sexe, les années écoulées depuis la diplomation de la faculté de médecine, la région géographique de la pratique, et les caractéristiques de la pratique comme le nombre total de patients hospitalisés, de patients ambulatoires, et la fréquence des visites des patients ambulatoires.

Résultats:

En 2013, il y avait 2 070 psychiatres, dont près de la moitié (47%) comptaient plus de 30 ans depuis la diplomation de la faculté de médecine. Les femmes psychiatres représentaient 41% de tous les psychiatres en 2013, mais 56% de tous les psychiatres comptant 15 ans et moins depuis la diplomation de la faculté de médecine. Entre 2003 et 2013, il y a eu une hausse de 17% du nombre total de psychiatres, l’accroissement le plus important s’étant produit dans le groupe comptant plus de 30 ans depuis la diplomation de la faculté de médecine. Au cours de ces 11 ans, le nombre moyen (ET) de patients ambulatoires uniques vus par un psychiatre annuellement est passé de 208 (228) à 249 (275) (19,5%; P = 0,001), les psychiatres masculins, en moyenne, voyant plus de patients ambulatoires annuellement que les psychiatres féminins.

Conclusion:

Le nombre de patients ambulatoires vus par des psychiatres s’accroît lentement. Toutefois, la forte proportion de psychiatres vieillissants, la concentration élevée des psychiatres en milieu urbain, et l’accroissement du nombre de psychiatres féminins dont la pratique est plus modeste suggèrent qu’à moins de changements radicaux de la façon dont pratiquent les psychiatres, l’accès aux psychiatres demeurera un problème en Ontario.

Access to psychiatrists is a challenge in Canada and internationally. In Canada, primary care physicians rated psychiatrists as the most challenging specialist to access.1 A study conducted in Vancouver, British Columbia, found that only 6 of 230 psychiatrists doing active clinical work were able to provide a consultation to a family health team in a timely manner.2 Patients also describe access to psychiatrists as challenging3: A study in the United States found that psychiatrists were more likely to accept private patients and less likely to provide services to patients covered by Medicaid or other insurance plans than were nonpsychiatrist specialists; the authors commented that this low acceptance rate poses a barrier to access.4 Psychiatrists are only one aspect of a responsive mental health system, which typically includes primary care physicians, psychologists, social workers, and other allied mental health professionals; psychiatrists typically adopt the role of providing and/or overseeing the delivery of specialist mental health or addictions care. Indeed, the United Kingdom5,6 and Australia7 have both responded to poor access to psychiatrists by integrating the services of psychologists and social workers into the publicly funded system to provide evidence-based therapy and by having psychiatrists adopt the role of consultants, and a similar initiative has been proposed for Canada.8

Previously, we reported that the supply of Ontario full-time psychiatrists is not equally distributed across the province, with many more psychiatrists practicing in Toronto and Ottawa than in suburban or rural regions.9 We also showed that as the supply of psychiatrists increased, the proportion of psychiatrists adopting low-volume practices increased. For example, approximately 10% of full-time psychiatrists in Toronto see fewer than 40 patients annually, compared with 4% in low-supply regions, and approximately 40% of full-time psychiatrists in Toronto see fewer than 100 patients annually, compared with 10% in low-supply regions. The patients seen by these psychiatrists were more likely to reside in the highest income neighbourhoods and less likely to have had a prior psychiatric hospitalization, compared with patients seen less frequently.

These findings led to the publication of a Globe and Mail op-ed10 and a Medical Post article11 questioning what roles a psychiatrist should assume in a publicly funded health care system. This study also raised questions among Ontario psychiatrists. For example, some psychiatrists wondered whether psychiatrists with low-volume practices were more likely to be older and close to retirement. This would mean that an increasing number of younger psychiatrists who see a large number of patients would solve the problem of access to psychiatrists, making the need to address these low-volume practices a less relevant issue. Academic psychiatrists responsible for training psychiatry residents were also interested in the impact of gender since more women than men are now accepted into psychiatry residency programs. Beyond these specific issues, there was a need to understand better the relationship between characteristics of Ontario psychiatrists and their practice.

While studies have described the profiles of US psychiatrists,12–15 these studies were based on self-reports and they reflect US psychiatry practices from the late 1990s. In the absence of similar studies of the Canadian psychiatrist workforce, we used population-based health administrative data to evaluate the characteristics (age, sex, practice region, and years since medical school graduation) and practice patterns of all psychiatrists in Ontario between 2003 and 2013. While the data are well-suited to provide information on regional psychiatrist supply, psychiatrist characteristics, and practice patterns, we are unable to provide direct information about quality of care or patient outcomes. Additionally, we focus specifically on psychiatrist demographics and practice pattern trends and therefore cannot comment on access to care beyond care provided by psychiatrists. Based on feedback from psychiatrists following our first study,9 we evaluated the adoption of low-volume patient practices by age category over time to determine whether there is a cohort effect. We also evaluated the proportion of female psychiatrists and their practice patterns over time to investigate the impact of the increased proportion of female psychiatrists.

Methods

Data Sources

Psychiatrist characteristics were obtained from the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES) Physician Database (IPDB). Patient records were linked using unique, anonymized, encoded identifiers across multiple Ontario health administrative databases containing information on all publicly insured, medically necessary hospital and physician services. Psychiatrist practice patterns were obtained from the Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP) database. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre.

Study Sample

We included all psychiatrists who submitted at least 1 billing claim to OHIP in each of the 11 years included in our study (2003 to 2013).

Psychiatrist Characteristics

We assessed the following characteristics for each psychiatrist on a yearly basis: age, sex, years since medical school graduation, region of practice (based on the 14 Ontario Local Health Integration Network [LHIN] boundaries). We determined whether psychiatrists worked full-time using the Health Canada definition of a full-time equivalent physician: having annual billings above the 30th percentile for all Ontario psychiatrists.16 For each psychiatrist and in each year of our study, we measured the number of unique outpatients (defined as any patient with at least 1 visit per year), number of new outpatients (defined as no visits in the 12 months prior to the first visit in the year of interest), and number of patient encounters, overall and by location (inpatient vs. outpatient). New patients were defined as those with no visits to the same psychiatrist in the preceding 12 months.

Statistical Analysis

We used chi-square for categorical comparisons and also used analysis of variance (ANOVA) to test for trends over time. We used SAS Version 9 for all statistical analyses.17

Results

In 2013, there were 2070 psychiatrists in Ontario who met our minimal clinical activity threshold of at least 1 submitted OHIP billing, with 1 in 5 (20.5%) psychiatrists within 15 years from their medical school graduation, 1 in 3 (32.8%) between 16 and 30 years, and nearly half (46.7%) over 30 years (Table 1). The average age of Ontario psychiatrists in these 3 categories was 38 (≤15 years from graduation), 50 (16-30 years from graduation), and 66 (>30 years from graduation). Female psychiatrists comprised 41% of all Ontario psychiatrists. While females made up 56% of all psychiatrists within 15 years of graduation from medical school, the proportion of female psychiatrists decreased as years from graduation increased. Overall, 3 of 5 (61.4%) of all Ontario psychiatrists graduated from Canadian medical schools: 80.0% of psychiatrists were within 15 years of graduation but only half (49.3%) of psychiatrists were more than 30 years. Finally, the number of psychiatrists in LHINs was highly variable, with 36% of all Ontario psychiatrists, and 41% of psychiatrists within 15 years of graduation, practicing in the Toronto Central LHIN.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Ontario psychiatrists in 2013 by years since medical school graduation.

| Years since medical school graduation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤15 y | 16-30 y | >30 y | Total | |

| n | 425 | 679 | 966 | 2070 |

| Age, mean (SD) | 38.2 (4.5) | 50.3 (5.6) | 65.7 (7.1) | 55.0 (12.5) |

| Sex, n (%) female | 238 (56.0) | 300 (44.2) | 305 (31.6) | 843 (40.7) |

| Canadian medical school graduate, n (%) | 340 (80.0) | 454 (66.9) | 476 (49.3) | 1270 (61.4) |

| Local Health Integration Network, n (%)a | ||||

| Erie St. Clair | 10 (2.4) | 18 (2.7) | 23 (2.4) | 51 (2.5) |

| South West | 33 (7.8) | 44 (6.5) | 76 (7.9) | 153 (7.4) |

| Waterloo Wellington | 19 (4.5) | 19 (2.8) | 33 (3.4) | 71 (3.4) |

| Hamilton Niagara | 33 (7.8) | 67 (9.9) | 64 (6.6) | 164 (7.9) |

| Mississauga Halton | 25 (5.9) | 29 (4.3) | 40 (4.1) | 94 (4.5) |

| Toronto Central | 176 (41.4) | 240 (35.3) | 332 (34.4) | 748 (36.1) |

| Central | 22 (5.2) | 50 (7.4) | 108 (11.2) | 180 (8.7) |

| Central East | 17 (4.0) | 32 (4.7) | 51 (5.3) | 100 (4.8) |

| South East | 10 (2.4) | 41 (6.0) | 41 (4.2) | 92 (4.4) |

| Champlain | 55 (12.9) | 90 (13.3) | 139 (14.4) | 284 (13.7) |

| North Simcoe Muskoka | 8 (1.9) | 10 (1.5) | 18 (1.9) | 36 (1.7) |

| North East | 11 (2.6) | 17 (2.5) | 15 (1.6) | 43 (2.1) |

| Full-time, n (%) | 289 (68.0) | 494 (72.8) | 687 (71.1) | 1470 (71.0) |

| Female full-time, n (%)b | 152 (63.9) | 204 (68.0) | 200 (65.6) | 556 (66.0) |

aThe North West and Central West Local Health Integration Networks are not reported because they had too few psychiatrists in certain categories such that particular psychiatrists could potentially be identifiable.

bThe percentage was calculated using the number of female psychiatrists within each category as the denominator.

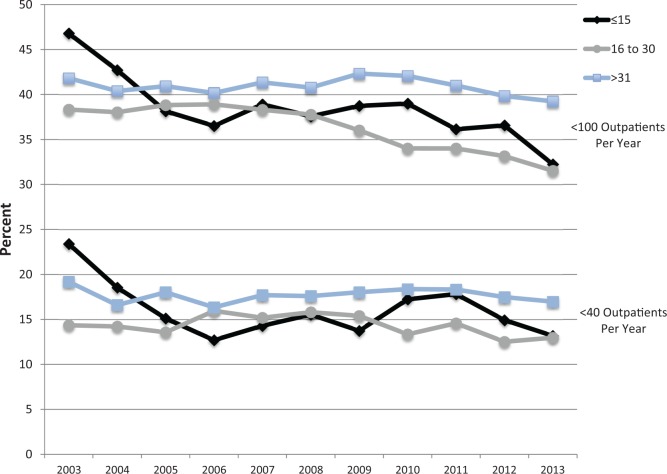

Assessing changes in the supply of Ontario psychiatrists over time, the total number of psychiatrists increased from 1775 to 2017 (an increase of 16.6%) between 2003 and 2013 (Table 2). In the same period, the number of psychiatrists more than 30 years since graduation increased from 641 to 966 (an increase of 50.7%). The number of psychiatrists within 15 years of graduation increased from 312 to 425 (36.2%), and the number of psychiatrists between 16 and 30 years since graduation decreased from 822 to 679 (–17.4%). The mean (SD) number of unique outpatients seen by a psychiatrist annually increased from 208 (228) to 249 (275) (19.5%; P = 0.001), whereas the mean (SD) number of unique inpatients seen annually increased from 54 (112) to 60 (110) (11.6%; P = 0.003). The proportion of all psychiatrists who saw fewer than 40 outpatients annually decreased from 310 (17.5% of all psychiatrists in 2003) to 299 (14.5% of all psychiatrists in 2013) (P = 0.12), and the proportion of psychiatrists who saw fewer than 100 outpatients annually decreased from 729 (41.1%) to 730 (35.3%) (P = 0.25). The proportion of psychiatrists within each cohort based on the period of time since graduation from medical school (≤15, 16-30, and >30) who saw fewer than 40 and 100 outpatients annually is shown in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Psychiatrist demographics and practice characteristics from 2003 to 2013.

| 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total no. of psychiatrists | 1775 | 1785 | 1803 | 1821 | 1834 | 1876 | 1932 | 1956 | 2021 | 2049 | 2070 |

| Sex, n (%) female | 625 (35.2) | 638 (35.7) | 656 (36.4) | 677 (37.2) | 685 (37.4) | 707 (37.7) | 734 (38.0) | 754 (38.5) | 798 (39.5) | 812 (39.6) | 843 (40.7) |

| Years from graduation, n (%) | |||||||||||

| ≤15 years | 312 (17.6) | 302 (16.9) | 291 (16.1) | 315 (17.3) | 329 (17.9) | 354 (18.9) | 364 (18.8) | 377 (19.3) | 404 (20.0) | 402 (19.6( | 425 (20.5) |

| 16-30 years | 822 (46.3) | 802 (44.9) | 796 (44.1) | 784 (43.1) | 731 (39.9) | 715 (38.1) | 708 (36.6) | 697 (35.6) | 700 (34.6) | 703 (34.3) | 679 (32.8) |

| >30 years | 641 (36.1) | 681 (38.2) | 716 (39.7) | 722 (39.6) | 774 (42.2) | 807 (43.0) | 860 (44.5) | 882 (45.1) | 917 (45.4) | 944 (46.1) | 966 (46.7) |

| Total annual unique outpatients, mean (SD) | 208 (228) | 214 (235) | 217 (236) | 219 (241) | 220 (249) | 224 (257) | 227 (264) | 231 (266) | 237 (274) | 241 (275) | 249 (275) |

| Total annual unique inpatients, mean (SD) | 54.1 (111.8) | 57 (119) | 57 (118) | 56 (117) | 56 (115) | 56 (110) | 57 (110) | 58 (109) | 59 (113) | 58 (111) | 60 (110) |

| <40 total annual outpatients, n (%) | 310 (17.5) | 281 (15.8) | 281 (15.6) | 279 (15.4) | 293 (16.0) | 308 (16.4) | 305 (15.9) | 315 (16.1) | 337 (16.7) | 308 (15.1) | 299 (14.5) |

| <100 total annual outpatients, n (%) | 729 (41.1) | 709 (39.7) | 713 (39.5) | 710 (39.0) | 728 (39.7) | 732 (39.0) | 760 (39.3) | 755 (38.6) | 760 (37.6) | 756 (36.9) | 730 (35.3) |

Figure 1.

Proportion of psychiatrists who see fewer than 40 and 100 outpatients total annually by years since medical school graduation, 2003-2013.

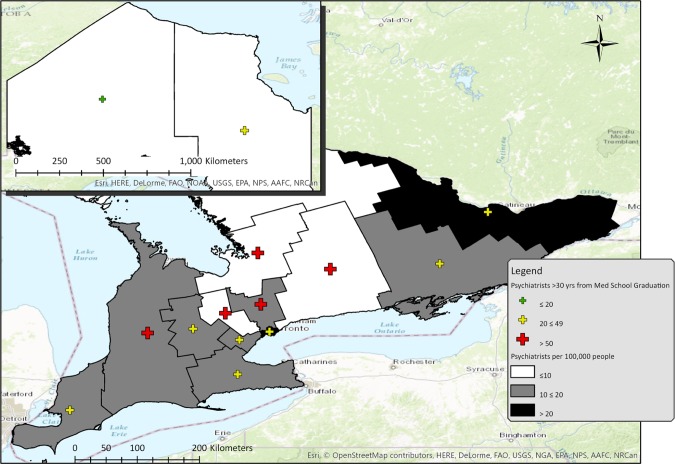

The per capita distribution of Ontario psychiatrists in 2013, including the years since graduation, by LHIN is shown in Table 3 and Figure 2. The Toronto Central LHIN had the highest number of psychiatrists per capita (61.0 psychiatrists per 100,000) whereas the Central West LHIN had the lowest (4.2 psychiatrists per capita), a 15-fold difference in psychiatrist supply. The LHINs with large urban centres (Toronto Central, Champlain [Ottawa], and Hamilton Niagara [Toronto Western suburbs and Hamilton]) had the largest proportion of recent graduates; the rural LHINs tended to have the highest proportion of psychiatrists 30 years or more from medical school graduation.

Table 3.

Regional per capita supply of psychiatrists and regional proportions by sex, graduation year, and country in 2013.

| Psychiatrists per capita, n/100,000 | Years since graduation from medical school, % | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female, % | ≤15 y | 16-30 y | >30 y | Canadian graduate, % | ||

| Total | 15.3 | 40.7 | 20.5 | 32.8 | 46.7 | 61.4 |

| Erie St. Clair | 8.0 | 25.5 | 19.6 | 35.3 | 45.1 | 29.4 |

| South West | 15.9 | 39.9 | 21.6 | 28.8 | 49.7 | 48.4 |

| Waterloo Wellington | 9.3 | 31.0 | 26.8 | 26.8 | 46.5 | 42.3 |

| Hamilton Niagara | 11.6 | 47.6 | 20.1 | 40.9 | 39.0 | 58.5 |

| Central West | 4.2 | 27.0 | 8.1 | 29.7 | 62.2 | 29.7 |

| Mississauga Halton | 7.9 | 40.4 | 26.6 | 30.9 | 42.6 | 52.1 |

| Toronto Central | 61.0 | 43.2 | 23.5 | 32.1 | 44.4 | 75.5 |

| Central | 9.9 | 39.4 | 12.2 | 27.8 | 60.0 | 50.0 |

| Central East | 6.3 | 33.0 | 17.0 | 32.0 | 51.0 | 40.0 |

| South East | 18.7 | 35.9 | 10.9 | 44.6 | 44.6 | 53.3 |

| Champlain | 22.0 | 45.4 | 19.4 | 31.7 | 48.9 | 68.3 |

| North Simcoe Muskoka | 7.7 | 19.4 | 22.2 | 27.8 | 50.0 | 69.4 |

| North East | 7.6 | 41.9 | 25.6 | 39.5 | 34.9 | 39.5 |

| North West | 7.2 | 41.2 | 17.6 | 64.7 | 17.6 | 88.2 |

Figure 2.

Geographical distribution of psychiatrist supply and proportion of psychiatrists more than 30 years from medical school graduation.

Practice characteristics in 2013 by psychiatrist sex and cohort since medical school graduation are shown in Table 4. Male psychiatrists saw a higher number of unique outpatients, unique inpatients, unique total patients, and new patients in each cohort since medical school. Female psychiatrists had a higher mean number of visits per patient than male psychiatrists. In each cohort, both male and female psychiatrists 16 to 30 years since graduation saw more unique outpatients than their older and younger counterparts, whereas the number of unique inpatients seen annually decreased as time since graduation increased. Similarly, the number of new outpatients seen per year decreased and the mean number of visits per patient increased as the years since graduation increased.

Table 4.

Practice characteristics of Ontario psychiatrists in 2013 by age and sex.

| Females | Males | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years since graduation from medical school | Years since graduation from medical school | Years since graduation from medical school | |||||||

| ≤15 y | 16-30 y | >30 y | ≤15 y | 16-30 y | >30 y | ≤15 y | 16-30 y | >30 y | |

| No. of visits, total | 958 (754) | 1053 (833) | 1053 (798) | 1374 (1029) | 1704 (1450) | 1605 (1472) | 1141 (908) | 1416 (1258) | 1431 (1322) |

| No. of visits, outpatient | 601 (516) | 813 (598) | 938 (749) | 832 (678) | 1175 (1056) | 1345 (1297) | 703 (603) | 1015 (901) | 1216 (1167) |

| No. of visits, inpatient | 357 (573) | 240 (501) | 115 (359) | 542 (712) | 529 (837) | 261 (592) | 438 (644) | 401 (722) | 215 (534) |

| No. of unique patients total | 239 (201) | 224 (210) | 184 (198) | 366 (265) | 383 (345) | 319 (362) | 295 (239) | 313 (306) | 276 (326) |

| No. of unique outpatients | 182 (174) | 192 (178) | 166 (180) | 285 (240) | 315 (313) | 289 (337) | 227 (212) | 261 (269) | 250 (302) |

| No. of unique inpatients | 71 (102) | 48 (91) | 24 (72) | 111 (135) | 94 (140) | 45 (98) | 89 (119) | 74 (123) | 39 (91) |

| No. of new outpatients | 139 (141) | 119 (133) | 86 (125) | 218 (199) | 192 (211) | 150 (235) | 174 (174) | 160 (184) | 130 (209) |

| No. of visits per outpatient per year | 3.9 (3.1) | 6.8 (7.5) | 9.6 (9.7) | 3.1 (1.9) | 5.3 (6.4) | 8.5 (99) | 3.6 (2.7) | 6.0 (7.0) | 8.8 (9.8) |

All results shown as mean (SD).

Discussion

Our study describes Ontario psychiatrists and their current pattern of practice as well as changes over the previous decade. Currently, there are a large number of psychiatrists more than 30 years since graduation from medical school or within 15 years of graduation, with relatively few mid-career psychiatrists. Ontario psychiatrists practice predominantly in urban areas, with 40% of Ontario psychiatrists working in the Toronto Central LHIN where only 10% of the Ontario population reside. Overall, there has been a statistically significant but modest increase in the average number of outpatients seen annually and no statistically significant change in the proportion of psychiatrists seeing fewer than 40 or 100 outpatients annually.

The practice patterns of psychiatrists vary by age and sex of the psychiatrists, with recent graduates seeing fewer outpatients than older psychiatrists and female psychiatrists seeing fewer patients (both inpatients and outpatients) than their male counterparts regardless of their cohort. Over the past decade, the proportion of psychiatrists who are female has increased, and the proportion of female psychiatrists is expected to continue to increase over time based on recent and current Canadian residency training programs with a larger proportion of female trainees. Thus, the lower practice volume of female psychiatrists is expected to affect access to care even more than the differential pattern of practice we observed in age cohorts. It may be that the lower outpatient volumes and higher visit frequency observed in female psychiatrist practices are associated with higher quality of care, as has been observed in female primary care physicians.18 However, the differential practice patterns of younger and female psychiatrists who are increasingly practicing in urban areas should worsen the access to psychiatrists in already underserved regions. Our data do not explain the reasons why younger and female psychiatrists see fewer patients, but these reasons are likely complex and multifactorial. Further quantitative and qualitative studies examining psychiatrist demographic factors with respect to quality of care provided and patient outcomes are necessary.

Another significant finding of our study is that despite the need for greater access to psychiatrists, the practice patterns of psychiatrists have remained largely unchanged over the 11-year study period. Our results suggest that the addition of younger psychiatrists to the current supply of Ontario psychiatrists will not solve the demand for increased access to their services. The role of psychiatrists, and, more specifically, how they practice and engage in the broader health care system, will need to change radically to accommodate the psychiatrist demographic shifts highlighted by our data: many older male psychiatrists nearing retirement being replaced by an increasing proportion of younger female psychiatrists who see fewer patients.

There are a number of possible explanations for our findings. The Ontario fee schedule does not impose any limits on the duration or frequency with which a patient is seen. This may provide an incentive to see a small number of familiar patients repeatedly and a disincentive to see more patients or new patients. In Australia, changes in the psychiatry fee schedule have created disincentives for high-frequency repeat patient visits. The resulting reduced frequency of patient visits and larger number of patients being seen suggest that financial incentives are effective at changing psychiatrist practice patterns.19 However, the fee schedule is the same for all Ontario psychiatrists, so the varied practice patterns observed across regions with high versus low psychiatrist supply and across age and gender groups are clearly influenced by factors other than the fee schedule. The data we used are ideal for describing what is happening, but other studies are needed to explain why we observed these variations in practice by region, age, and gender.

In response to rising health care costs in the United States, health management organizations and behavioural health “carve-outs” were developed, and the organization of psychiatric care for those with health insurance coverage changed.20 Along with these reforms, the role of a psychiatrist in the United States within these new managed care systems also changed, and the changes were met with significant criticism early on,21 which continues to this day.22 Thus, while the behavioural health carve-outs are associated with efficiency,23 the gains in efficiency appear to be at the cost of psychiatrist job satisfaction, related to the perception that psychiatrists are less autonomous in the way they can provide care to patients. In contrast, our study suggests that Ontario psychiatrists have not been “managed,” with little change in practice patterns over the past decade despite an increasing awareness of a substantial amount of unmet need for psychiatric services24 and, according to Canada’s Wait Time Alliance, no current way to systematically assess access to psychiatric care.25 There is an opportunity for Ontario psychiatrists, as self-regulating professionals, to be better integrated within the broader array of health services to align psychiatrists as a finite human resource with the existing need. In the absence of better integration, Ontario psychiatrists may lose their autonomy and face practice restrictions similar to restrictions faced by Quebec psychiatrists (e.g., restrictions on where they can practice) or by US psychiatrists (e.g., restrictions on the treatment they can provide to their patients), with the risk of erosion of job satisfaction. Looking towards the future, Canadian psychiatry residency programs are preparing for the introduction of competency-based education in psychiatry residency, a mode of training that incorporates (1) identifying outcomes that need to be achieved through training; (2) defining performance levels or standards for each competency; (3) developing an evaluation framework for competencies; and (4) continuously evaluating competency-based medical education to see whether it is indeed producing the desired outcome of competent psychiatrists.26,27 The development of core competencies provides a unique opportunity to redefine and modify the role of future psychiatrists in Ontario.

In summary, this study provides a quantitative evaluation of the current Ontario psychiatrist work force, their pattern of practice, and changes over time. Our results suggest that, absent some radical changes in the way Ontario psychiatrists practice, 2 impactful demographic trends will worsen the access to psychiatrists in Ontario: a large number of older male psychiatrists (with large outpatient practices) nearing retirement and a large number of younger and female psychiatrists (with relatively smaller outpatient practices) entering the work force. Access to psychiatrists outside of urban settings will become even more challenging given the regional distribution of psychiatrists, with the majority of psychiatrists already practicing in large urban settings and an even larger proportion of newer psychiatrists establishing their practice in the Greater Toronto Area. Increasing access to psychiatrists while preserving, or enhancing, quality of care will be a challenge for an evolving mental health system. We hope that the information from this study will be helpful to psychiatrists and policymakers trying to address access to mental health care.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Michael Collins for his help in creating the map shown in Figure 2.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Dr. Paul Kurdyak received operational grant funding from the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC) Health Services Research Fund Capacity Award (Grant 06682). Dr. Kurdyak’s and Dr. Mulsant’s work is supported in part by the Medical Psychiatry Alliance, a collaborative health partnership of the University of Toronto, the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, the Hospital for Sick Children, Trillium Health Partners, the Ontario MOHLTC, and an anonymous donor. The Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES) is funded by the Ontario MOHLTC. The study results and conclusions are those of the authors and should not be attributed to any of the funding agencies or sponsoring agencies. No endorsement by ICES or the Ontario MOHLTC is intended or should be inferred.

References

- 1. http://nationalphysiciansurvey.ca/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/2010-FP-Q13.pdf National Physician Survey: patient access to care Mississauga [Internet]; 2010 [cited 2011 Aug 25]

- 2. Goldner EM, Jones W, Fang ML. Access to and waiting time for psychiatrist services in a Canadian urban area: a study in real time. Can J Psychiatry. 2011;56(8):474–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bydlowska J. Finding a psychiatrist in Toronto is like hunting a unicorn. The Toronto Star. 2015 Apr 9; Health and Wellness Sect. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bishop TF, Press MJ, Keyhani S, Pincus HA. Acceptance of insurance by psychiatrists and the implications for access to mental health care. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(2):176–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hope R. Mental Health: New ways of working for everyone [Internet]. London: National Institute for Mental Health in England; 2007. [cited 2011 Jun 13]. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_074495.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bhugra D. http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/usefulresources/publications/collegereports/op/op74.aspx Role of the consultant psychiatrist. Occasional Paper OP74 [Internet] [published 2010; cited 2011 Jun 13]

- 7. National action plan on mental health 2006-2011. Australia: Council of Australian Governments (COAG); 2006. p. 41.

- 8. Cohen K, Peachey D. Access to psychological services for Canadians: getting what works to work for Canada’s mental and behavioural health. Can Psychol. 2014;55(2):126–130. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kurdyak P, Stukel T, Goldbloom D, Zagorski B, Kopp A, Mulsant B. Universal coverage without universal access: a study of psychiatrist supply and practice patterns in Ontario. Open Med. 2014;8(3):87–99. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kurdyak P, Goldbloom D. Can’t find a psychiatrist? Here’s why. Globe and Mail. 2014 Jul 17; Opinion. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bronca T. Treating the worried well—for a career? The Medical Post. 2014 Oct 20; Physicians. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zarin DA, Pincus HA, Peterson BD, West JC, Suarez AP, Marcus SC, et al. Characterizing psychiatry with findings from the 1996 National Survey of Psychiatric Practice. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(3):397–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Marcus SC, Suarez AP, Tanielian TL, Pincus HA. Datapoints: trends in psychiatric practice, 1988-1998: I. Demographic characteristics of practicing psychiatrists. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(6):732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tanielian TL, Marcus SC, Suarez AP, Pincus HA. Datapoints: trends in psychiatric practice, 1988-1998: II. Caseload and treatment characteristics. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(7):880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Suarez AP, Marcus SC, Tanielian TL, Pincus HA. Datapoints: trends in psychiatric practice, 1988-1998: III. Activities and work settings. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(8):1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Canadian Institute for Health Information. Full-time equivalent physicians report, fee-for-service physicians in Canada, 2004-2005. Ottawa: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 17. SAS system version 9: installation and administration information. Cary (NC): SAS Institute; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Borges Da Silva R, Martel V, Blais R. Qualité et productivité dans les groupes de médecine de famille: qui sont les meilleurs? Les hommes ou les femmes? Revue d’epidémiologie et de santé publique. 2013;61(S4):S210–S2S1. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Doessel DP, Scheurer RW, Chant DC, Whiteford H. Financial incentives and psychiatric services in Australia: an empirical analysis of three policy changes. Health Econ Policy Law. 2007;2(Pt 1):7–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Feldman S. Behavioral health services: carved out and managed. Am J Manag Care. 1998;4(Suppl):SP59–SP67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Goleman D. Psychiatrists under pressure: a special report: health; new paths to mental health put strains on some healers. New York Times. 1990. May 17; Health. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Harris G. Talk doesn’t pay, so psychiatry turns instead to drug therapy. New York Times. 2011. May 5; Health. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Goldman HH, Frank RG, Burnam MA, Huskamp HA, Ridgely MS, Normand SL, et al. Behavioral health insurance parity for federal employees. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(13):1378–1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sunderland A, Findlay LC. Perceived need for mental health care in Canada: results from the 2012 Canadian Community Health Survey-Mental Health. Health Rep. 2013;24(9):3–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Eliminating code gridlock in Canada’s health care system: 2015 Wait Time Alliance report card. Ottawa (ON): Wait Times Alliance; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Frank JR, Mungroo R, Ahmad Y, Wang M, De Rossi S, Horsley T. Toward a definition of competency-based education in medicine: a systematic review of published definitions. Med Teach. 2010;32(8):631–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Iobst WF, Sherbino J, Cate OT, Richardson DL, Dath D, Swing SR, et al. Competency-based medical education in postgraduate medical education. Med Teach. 2010;32(8):651–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]