Abstract

Objectives:

We aimed to investigate the effectiveness of a day visit in changing attitudes towards a high-security forensic psychiatric hospital, with regard to the current recruitment difficulties in psychiatry.

Methods:

Broadmoor Hospital, a UK high-security psychiatric hospital, runs day visits for medical students, led by doctors. At the beginning and the end of the day students wrote their responses to the question, ‘What do you think of Broadmoor?’ Attitudes and themes were identified, and their prevalence was analysed.

Results:

The responses of 296 students were initially analysed; however, 19 responses had to be excluded because they were illegible or incomplete. Before the visit, 15 responses were rated as positive, 169 neutral and 93 negative. After the visit, 205 responses were positive, 69 neutral and three negative. The themes that changed markedly following the visit were those indicating a change to favourable attitude.

Conclusions:

A single day visit was shown to be effective in altering the attitudes of medical students towards forensic psychiatry within a high-security psychiatric hospital.

Keywords: forensic psychiatry, medical students, attitude, psychiatry, recruitment

Recent statistics from the Royal College of Psychiatrists UK report a shortfall in recruitment of psychiatrists, with the percentage of newly qualified doctors choosing a career in psychiatry being consistently low1 and spaces in rotations not being fully filled.2

Disregard for psychiatry as a specialty of choice has been shown to be influenced by stigma,3 being perceived as lacking scientific basis, a difficult and pressured work environment and lacking in resources.4,5 A positive attitude towards psychiatry has been found to correlate with an intention to pursue it as a career.6 The quality and extent of psychiatric experience during medical school affect attitudes towards the specialty, and can guide the decision to choose psychiatry as a career. Enrichment experience and attachments in psychiatry can extend this experience beyond standard teaching and placements and improve attitudes to psychiatry.7,8

We report an evaluation of the attitudes of medical students before and after a single day visit to a high-security forensic psychiatric hospital in England. Our aim was to investigate if the 1-day placement led to a change in the attitude towards high-security forensic psychiatry as assessed on that day.

Method

Participants and procedures

The study was a qualitative survey of fourth-year medical students (n = 296) on 1-day visits to Broadmoor High-security Psychiatric Hospital. High-security hospitals treat patients who have committed serious offences, have severe psychiatric conditions and therefore pose the highest level of risk to others such that they cannot be managed in other security settings. Typically, the most common diagnosis is schizophrenia followed by personality disorder. This survey was carried out as an evaluation of the medical education service provided by the hospital, hence no ethical approval was required.

Students visited in groups of 10–20 from University of Oxford, Imperial College, St George’s University London, King’s College London and Barts and The London School of Medicine. A consultant psychiatrist and trainee (core or higher training) working at Broadmoor Hospital hosted the visits. The 6-hour day programme began with an interactive question and answer session and brief introduction to the hospital, followed by 1.5 hours spent on the ward where the students interviewed patients under supervision. This was followed by a discussion of findings from the patient interviews. There was then a tour of the hospital and a 2-hour interactive teaching session on forensic psychiatry.

Students were assessed at the beginning (baseline) and end (follow-up) of the session. At baseline, before teaching began, they were given a blank piece of paper and asked to answer the question, ‘What do you think of Broadmoor?’. Students answered the question in free text and responses were anonymous. Students were not informed that they would be answering the question again in the afternoon. In order to match baseline and follow-up responses, each response in the morning was given a number for the given student by an administrator. Students were informed that their responses would be anonymous in order to maintain confidentiality.

A follow-up survey was conducted at the end of the day. Baseline responses were returned to the students, and on the opposite side of the paper they again answered the question, ‘What do you think of Broadmoor?’ This question was chosen as the question that best captured what we were trying to assess following a focus group of psychiatric trainee doctors.

Data analysis

All the responses were evaluated by two raters (AA, JG) using previously reported techniques of thematic analysis.9

The raters examined a random sample of responses (n = 50) and recorded the 30 most commonly occurring themes. A ‘theme’ was any subject matter or idea mentioned in the response. All responses in the data set were then evaluated for the presence of these 30 themes.

Working definitions of the themes derived for the raters with example comments by respondents in brackets are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Definitions of themes with quotes from students in brackets

| Security/high security | Focus on security and restrictive aspects of the service delivered such as physical security, procedures, restrictions in freedom, intensive and intrusive monitoring (I think that patients at Broadmoor Hospital are locked up in cells, are not allowed much freedom to do much at all) |

| Prison | Focus on high secure hospital as a custodial setting like a prison rather than a hospital, where the emphasis is more on punishment and deterrence (It is no different to a prison really, except that it is called a hospital. The inmates are all locked up, how can one really treat people in such a setting?) |

| Criminals | Focus on patients in a high secure hospital being predominantly of criminal background rather than suffering from a mental disorder (All the people locked up are really criminals, who are conning and exploiting the system. Maybe they are malingering a mental illness!) |

| Danger | Focus on patients in such a setting as being extremely dangerous, and perhaps not amenable to modern psychiatric treatments (I think it is a spooky dangerous place, filled with rapist, serial killers and murderers. It must be scary to work with these psychopaths. Do they ever get better at all?) |

| Rehabilitation | Focus on the hospital being a setting where treatment focuses on risk reduction, symptom improvement and restoration of patients to society (I hear that the patients receive good treatment and their risk reduces. They are then discharged to the community and do not reoffend) |

| Humane/therapeutic | Focus on psychiatric treatment delivered with dignity, compassion, care and consideration (The staff are really very caring, and treat the patients with empathy and compassion, no matter what they have committed) |

The raters (AA, JG) also assessed the overall attitude of each response as either positive, negative, neutral/balanced or indiscernible. Attitude was classed as positive if a response expressed more favourable than unfavourable or neutral ideas. Negative attitude was defined as a response that was composed of more unfavourable than neutral or favourable ideas. Indiscernible applied to responses that were illegible or incomplete. Neutral/balanced applied to responses that were purely factual or recorded an equal mix of positive and negative comments

Descriptive analysis was carried out with SPSS Version 20.

Results

In total 296 students completed the survey. Nineteen responses had to be excluded because they were classified indiscernible. Thus n = 277 responses were analysed.

Inter-rater reliability of thematic analysis raters

As more than one rater assessed which themes and attitudes were reflected in the medical students’ answers, we tested our inter-rater agreement using Cohen’s kappa for two raters independently assessing 20 responses. Cohen’s kappa was found to be 0.91 (95% confidence intervals, 0.74–1.00), indicating a high level of inter-rater agreement.

Nature of attitudes at ‘baseline’ and ‘follow-up’

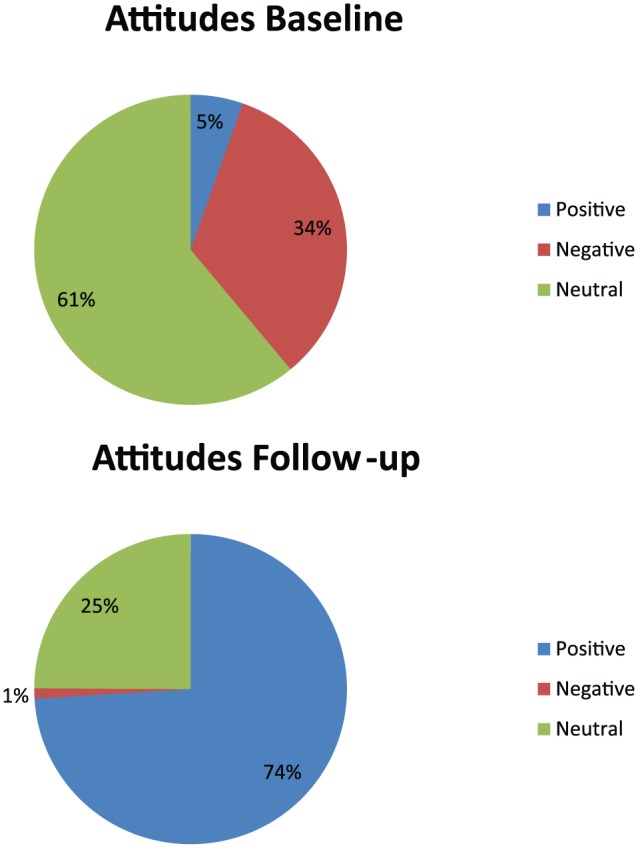

The majority of responses at baseline were neutral/balanced (169, 61%), with few responses demonstrating an overall positive attitude (15, 5%). At follow-up, responses with an overall positive attitude were the most frequently recorded (205, 74%), with neutral/balanced and negative attitude responses reducing to 69 (25%) and three (1%), respectively (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Pie chart to show attitudes at baseline and follow-up after the visit.

Change in attitude was recorded for each participant as a positive change, no change or a negative change. For example, positive change included an attitude change following the visit from negative to neutral, negative to positive or from neutral to positive. In total, 207 (75%) participants were recorded as having expressed a positive change in attitude, 65 (23%) no change and five (2%) a negative change in attitude.

Themes at ‘baseline’ and ‘follow-up’

Prevalence of themes mentioned was analysed both across the entire data set and in different subgroups according to their attitude change.

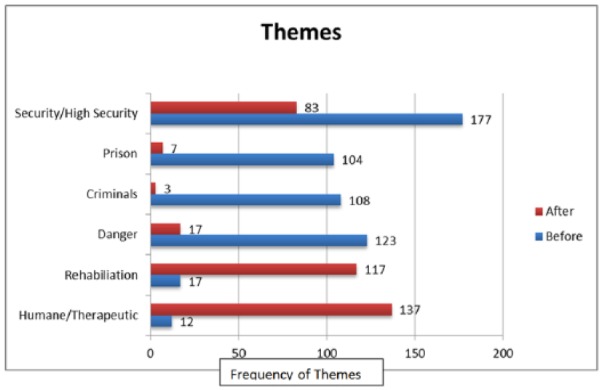

For the entire data set, the six themes seeing the greatest change in prevalence following the visit were: ‘Security/High-Security’, ‘Prison’, ‘Criminals’, ‘Danger’, ‘Rehabilitation’ and ‘Humane/Therapeutic’ (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Bar chart showing the six themes with most change in frequency following the visit.

Some qualitative comments by the students noted as ‘positive’ changes after the teaching programme are reproduced in Table 2.

Table 2.

Qualitative comments by students noted as positive change after teaching programme

| The patients were generally lot more stable than I thought and showed a good degree of normal functioning. |

| The hospital gives a lot of opportunities for rehabilitation and emphasis on psychological therapies and medication…. Patients get a sense of achievement and purpose. |

| I thought the patients were treated with a lot of care and compassion which helps in their recovery. |

| I am impressed that one in 4 patients are discharged every year and never come back. |

| The hospital has good outcomes, and the treatments are very effective in reducing risk. |

| I did not feel the patients were nasty or dangerous at all, I felt I could relate to them as human beings. |

| High secure hospitals have an important role in safeguarding society and rehabilitating dangerous mentally ill people. |

| I am surprised that the staff deliver some very good therapies and modern treatment for such a high-risk group. |

| I was surprised how the wards were more ‘like’ hospital wards rather than solitary prison detention centres. |

| It is a difficult area… balancing need for justice with need for rehabilitation… but I think these facilities are justified. |

| I did not feel anxious, as I thought I might during the visit… it was calm, and I saw good staff–patient relationships. |

| Therapeutic service, calm and contained atmosphere… Patients not scary… very difficult histories. |

| Initially felt a bit ‘zoo-like’ to come for a visit, but I can say it is a very modern and impressive hospital. |

| The newspapers portray Broadmoor as a scary and nasty place, I saw the opposite, the media can be wrong and likes to sensationalise. |

The ‘No Change’ group encompassed responses in which the attitude remained the same after the visit; however, the frequency of particular themes did change. In this subgroup of participants, the six themes seeing the greatest change from before to after the visit were ‘Danger’ from 27 to four, ‘Criminals’ from 22 to 0, ‘Security’ from 45 to 23, ‘Good Facilities/Modern’ from 1 to 18, ‘Prison’ from 17 to two and ‘High Profile/Infamous’ from 16 to one.

Discussion

We examined the effectiveness of a 1-day visit to Broadmoor Hospital in changing medical students’ attitudes towards a high-security forensic psychiatric hospital. The findings of this study demonstrate a positive change in attitude in the majority (207/277, 74.7%) of students. Analysis also showed a marked change in the themes raised by respondents before and after the visit. It was notable that in the group where attitudes remained the same before and after the visit, there was still a change in the themes raised within the content of their responses.

The six themes seeing the greatest change in frequency following the visit were: ‘Security/High Security’, ‘Prison’, ‘Criminals’, ‘Danger’, ‘Rehabilitation’ and ‘Humane/Therapeutic’. This is important, as whilst themes such as ‘Security/High-Security’ do not imply a particular attitude, their frequency does reveal the preoccupations of respondents before and after the visit. These changes in themes also relate closely to past studies examining reasons why psychiatry is not regarded as an attractive career option, such as being unscientific and not ‘real medicine’.5 The themes ‘Humane/Therapeutic’ and ‘Rehabilitation’, both relating to the role of the hospital in providing effective treatment to its patients, increased in frequency after the visit. The themes ‘Prison’, ‘Danger’ and ‘Criminals’ reduced vastly following the visit. They carry negative connotations and demonstrate a focus on the high-security element of the hospital.

The findings of this study also mirror the positive attitude changes seen in other studies following a psychiatric attachment10 or summer school.11 Other studies have been non-clinical, but over a longer period of time.11 In order to change an attitude towards a specialty, it is necessary to change one’s perception of the specialty first. By introducing students to patients and clinicians within an extreme environment perceptions can be changed dramatically over a short period of time, and we have shown this to be a highly effective way of changing attitudes. For a change in negative attitude, stigma also needs to be addressed and whilst we did not specifically examine this, it is likely that contact with a stigmatised group (Broadmoor patients) decreases stigma and improves attitudes.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The strengths of this study include its large sample size, and that students attending the visits did so as a compulsory part of their course and thus were not a self-selecting group. The fact that the feedback was taken immediately after the visit meant that it was representative of the students’ thoughts at the time, and the changes seen can be presumed to have been influenced by the visit itself. In addition, scoring by raters had high inter-rater reliability.

The main limitation to this study is the fact that the visit was to a highly specialised forensic psychiatry unit. It therefore may not be possible to apply these findings across the whole of psychiatry. Although this change was demonstrated on the day of the visit, the cross-sectional nature of the study means that it is unknown whether the attitude change was maintained in the long term.

Some variables may not have been constant for every student visit. These changes may have affected the experiences of the students and thus their responses.

As the raw data in the form of student responses was qualitative in nature, it was open to researcher bias. We believe, however, that the naturalistic approach of asking students to write their thoughts in free text has advantages over more structured questionnaire methods of assessing attitudes.

Implications

We have demonstrated that a structured 1-day exposure is an easily achievable and effective way of changing medical students’ attitudes towards a psychiatric sub-specialty. It is possible that, as shown by previous studies, students with a positive attitude towards psychiatry are more likely to choose it as a career than those with negative attitudes.6

It may be of interest to see if similar teaching strategies for medical students lead to an increase in recruitment of doctors into basic psychiatry training posts. Future research would benefit from long-term follow-up, in order to assess the longevity of the attitude change observed in our study.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors report no conflict of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Contributor Information

Ann Archer, Medical Student, Medical Sciences Division, John Radcliffe Hospital, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK.

Joshana Guliani, Medical Student, Medical Sciences Division, John Radcliffe Hospital, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK.

Francesca Johns, Medical Student, Medical Sciences Division, John Radcliffe Hospital, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK.

Emily McCartney, Medical Student, Medical Sciences Division, John Radcliffe Hospital, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK.

E Naomi Smith, Core Psychiatric Trainee Doctor, Broadmoor Hospital, West London Mental Health Trust, Crowthorne, Berkshire, UK.

Callum C Ross, Consultant Forensic Psychiatrist, Broadmoor Hospital, West London Mental Health Trust, Crowthorne, Berkshire, UK.

Samrat Sengupta, Consultant Forensic Psychiatrist, Broadmoor Hospital, West London Mental Health Trust, Crowthorne, Berkshire, UK.

Mrigendra Das, Consultant Forensic Psychiatrist, Broadmoor Hospital, West London Mental Health Trust, Crowthorne, Berkshire, UK, and; College Tutor, Oxford School of Psychiatry, Oxford, UK, and; Consultant Forensic Psychiatrist, Top End Mental Health Service, Parap, NT, Australia.

References

- 1. Goldacre MJ, Turner G, Fazel S, et al. Career choices for psychiatry: National surveys of graduates of 1974–2000 from UK medical schools. Br J Psychiatry 2005; 186: 158–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Royal College of Psychiatrists. Recruitment strategy 2011–2016. http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/pdf/Recruitment%20Strategy%20-%2010092013.pdf

- 3. Curtis-Barton MT, Eagles JM. Factors that discourage medical students from pursuing a career in psychiatry. Psychiatrist 2013; 35: 425–429. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Malhi GS, Coulston CM, Parker GB, et al. Who picks psychiatry? Perceptions, preferences and personality of medical students. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2011; 45: 861–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wigney T, Parker G. Medical student observations on a career in psychiatry. Australas Psychiatry 2007; 41: 726–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Farooq K, Lydall GJ, Malik A, et al. Why medical students choose psychiatry – a 20 country cross-sectional survey. BMC Med Educ 2014; 14: 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Halder N, Hadjidemetriou C, Pearson R, et al. Student career choice in psychiatry: Findings from 18 UK medical schools. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2013; 25: 438–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Archdall C, Atapattu T, Anderson E. Qualitative study of medical students’ experiences of a psychiatric attachment. Psychiatrist 2013; 37: 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ryan GW, Bernard HR. Techniques to identify themes. Field Methods 2003; 15: 85–109. [Google Scholar]

- 10. McParland M, Noble LM, Livingston G, et al. The effect of a psychiatric attachment on students’ attitudes to and intention to pursue psychiatry as a career. Med Educ 2003; 37: 447–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Beattie S, Lister C, Khan JM, et al. Effectiveness of a summer school in influencing medical students’ attitudes towards psychiatry. Psychiatrist 2013; 37: 367–371. [Google Scholar]