Summary

Episodic memory is thought to critically depend on interaction of the hippocampus with distributed brain regions [1–3]. Specific contributions of distinct networks have been hypothesized, with the hippocampal posterior-medial (HPM) network implicated in recollection of highly precise contextual and spatial information [3–6]. Current evidence for HPM specialization is mostly indirect, derived from correlative measures such as neural activity recordings. Here, we tested the causal role of HPM in recollection using network-targeted noninvasive brain stimulation in humans, which has previously been shown to increase functional connectivity within the HPM network [7]. Effects of multiple-day electromagnetic stimulation were assessed using an object-location memory task that segregated recollection precision from general recollection success. HPM network-targeted stimulation produced lasting (~24 h) enhancement of recollection precision, without effects on general success. Canonical neural correlates of recollection [8–10] were also modulated by stimulation. Late-positive evoked potential amplitude and theta-alpha oscillatory power were reduced, suggesting that stimulation can improve memory through enhanced reactivation of detailed visuospatial information at retrieval. The HPM network was thus specifically implicated in processing of fine-grained memory detail, supporting functional specialization of hippocampal-cortical networks. These findings demonstrate that brain networks can be causally linked to distinct and specific neurocognitive functions and suggest mechanisms for long-lasting changes in memory due to network-targeted stimulation.

Keywords: transcranial magnetic stimulation, hippocampus, retrieval, EEG, spatial memory, precision, theta

Results

Even when recollection of past episodes is successful, the amount of retrieved information can vary [11], providing memory for precise details in some cases (e.g., “The store was on the left, four blocks ahead of the first stop light.”) and more general memory in others (e.g., “The store was on the left side of the street.”). Several lines of evidence suggest preferential contributions to high-precision memory by the posterior hippocampus [6], including smaller receptive fields for posterior compared to anterior hippocampus ([12]; dorsal versus ventral in the rodent). Indeed, distinct functional large-scale networks of posterior versus anterior hippocampus and surrounding parahippocampal regions [13] have been hypothesized to differentially support precise versus general/gist-based memory, respectively [3–6]. However, there is little direct evidence for the reliance of recollection precision on distributed functional brain networks. To test the hypothesized involvement of the HPM network in memory precision, we used noninvasive electromagnetic stimulation methods that increase functional connectivity of the HPM network [7] in conjunction with a graded assessment of associative object-location memory (Figure 1A) designed to segregate recollection precision from general success [11]. We predicted that HPM network-targeted stimulation would improve memory precision and modulate established EEG correlates of recollection [8].

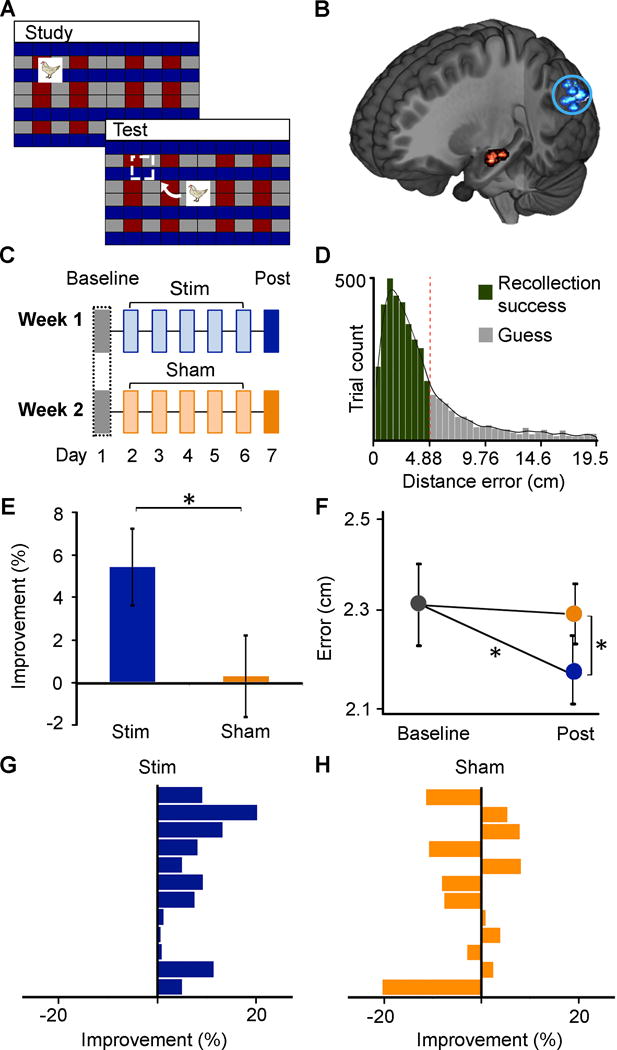

Figure 1. HPM network-targeted stimulation enhanced recollection precision.

A. Participants studied trial-unique objects at randomly assigned locations. Subsequent memory testing involved object-cued recall of locations. B. fMRI connectivity used anatomically defined hippocampal body seeds (red) to define parietal-maximum stimulation locations (blue, circled) in each participant. Each dot indicates locations for one participant (see Figure S1). C. Five daily sessions of Stim or Sham stimulation followed Baseline memory testing. Post-Stim and Post-Sham testing followed the final daily stimulation session by ~24 hours. Stim and Sham conditions were administered within-subjects in counterbalanced order. D. Histogram of distance error for all participants and conditions. Successful recollection (green) and guessing (gray) trials were defined via converging modeling approaches (see Supplemental Experimental Procedures). E. Percent-improvement from Baseline was significantly above zero for Post-Stim but not Post-Sham and significantly greater for Post-Stim than Post-Sham. F. Distance error for successful recollection was reduced Post-Stim relative to Baseline (but not Post-Sham relative to Baseline) and Post-Stim relative to Post-Sham (see Table S1). G. Percent change in precision due to Stim for each participant. H. Percent change in precision due to Sham for each participant *p<0.05

There is high anatomical [14] and fMRI connectivity [13, 15] between lateral-parietal cortex and hippocampus. We have previously shown that five daily sessions of repetitive high-frequency transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) delivered to stimulation-accessible parietal-cortex locations enhances fMRI connectivity between posterior hippocampus and the associated retrosplenial, parahippocampal, medial-parietal, and lateral-parietal HPM cortical network regions [7]. We identified participant-specific stimulation locations in the lateral-parietal cortex based on high resting-state fMRI connectivity with anatomically defined left-hippocampal seed locations (Figure 1B, Figure S1), in order to noninvasively target the HPM network.

Sixteen participants completed a two-week, sham-controlled, counterbalanced paradigm (Figure 1C), involving memory testing ~24 hours before and after HPM network-targeted stimulation (Stim) compared to rTMS of the same intensity delivered to the vertex, a location outside of the HPM network (Sham) (see Supplemental Experimental Procedures for further details). At each of the assessments (Pre-Stim, Post-Stim, Pre-Sham and Post-Sham), EEG was collected during memory recall of 96 unique object locations (Figure 1A). Pre-Stim and Pre-Sham data were collapsed into a common Baseline. Main analyses include data from only the participants that contributed to EEG comparisons (n=12), although the same pattern of selective effects on recall precision was found in the entire sample (see below and Supplemental Experimental Procedures for more details).

Network-Targeted Stimulation Selectively Improved Recollection Precision

Trials were scored for distance error (difference between recalled and studied locations) and sorted into successful recollection (67.6% of trials, SE=4.5%) and guess conditions using a two-parameter model that segregates recollection precision from general recollection success [11] (Figure 1D, see Supplemental Experimental Procedures). We did not hypothesize effects of stimulation on general recollection success, which was tested using two complementary approaches. First, the proportion of trials categorized as reflecting successful recollection (distance errors less than the 4.88-cm threshold, see Supplementary Methods) did not significantly change Post-Stim (t(11)=1.88, p=0.26) or Post-Sham (t(11)=0.18, p=0.86) relative to Baseline. Second, the same growth-mixture fitting was used to define the group-level threshold for recollection success was used to estimate successful recollection for each participant and memory assessment ([11]; see Supplementary Methods). Individualized successful recollection thresholds did not significantly differ for Pre-Stim versus Post-Stim (t(11)=0.603, p=0.56) nor for Pre-Sham versus Post-Sham (t(11)=0.591, p=0.57). Both methods thus converged to indicate that stimulation did not alter general recollection success.

Precision was defined as the mean distance error for successful recollection trials [11]. In contrast to general success, recollection precision measured Post-Stim improved relative to Baseline (t(11)=2.99, p=0.01; Cohen’s d=0.86), but not for Post-Sham relative to Baseline (t(11)=0.14, p=0.89) (Figure 1E). The percent-improvement from Baseline was significantly greater for Post-Stim than Post-Sham (t(11)=2.63, p=0.02; Cohen’s d=0.76). Furthermore, raw distance error (Figure 1F) was less for Post-Stim than for Post-Sham (t(11)=2.68, p=0.02, Cohen’s d=0.77). Thus, HPM network-targeted stimulation (and not Sham) improved recollection precision. Recollection precision improvements were highly consistent across subjects due to Stim (12/12 improved; Figure 1G; Sign Test p<0.0005) but were at chance due to Sham (6/12 improved; Figure 1H; Sign Test p=1.0). Similar effects of stimulation were identified when individual Pre-Stim and Pre-Sham values were used rather than the common Baseline (see Supplemental Experimental Procedures), confirming that stimulation improved precision irrespective of the choice of baseline. Precision improvements were also highly consistent in the entire N=16 sample. Percent-improvement values (Post versus Pre) were significantly greater for Stim than for Sham (t(15)=2.89, p=0.01; Cohen’s d=0.72), and precision improvements due to Stim were highly consistent across subjects (15/16 improved; Sign Test p=0.0005) but were at chance due to Sham (7/16 improved; Sign Test p=0.80) (see Supplemental Experimental Procedures for additional full-sample analysis details).

To test the possibility that the relative difference for Stim vs. Sham effects was due to impairments for Sham rather than improvements for Stim (as rTMS intensity for Stim and Sham was matched but with delivery to different locations), we also performed a separate control experiment in which zero-intensity stimulation was delivered to the HPM parietal target in an additional group of subjects (N=12; see Supplementary Methods). Precision memory was not reliably improved in this additional control condition. There was no significant change in raw error Post-Control versus Pre-Control (t(11)=1.57, p=0.145). Furthermore, improvements were not consistent across subjects (7/12 participants improved; Sign Test p=0.774; see Supplementary Results for more details). Precision improvements were therefore selective for Stim, and did not occur for either of the control conditions.

Network-Targeted Stimulation Reduced Evoked EEG Correlates of Recollection

Theta-alpha frequency oscillatory activity and late-positive event-related potentials (ERP) are stimulus-evoked neural correlates of recollection [9, 10]. We hypothesized that stimulation would modulate these neural signals of memory retrieval [16], providing neural correlates of the corresponding recollection precision improvement [17]. Many manipulations that increase the subjective experience of recollection and memory response accuracy correspond to increases in low-frequency oscillatory power and event-related late-positive ERP amplitude. However, reductions in oscillations and event-related potentials have also been associated with memory retrieval, specifically for sensory reactivation [18, 19] and increased flexibility for high-resolution information storage [20]. The nature of effects on EEG/ERP correlates of memory retrieval (i.e., enhancements or reductions) therefore can provide mechanistic insights regarding precision improvement due to Stim.

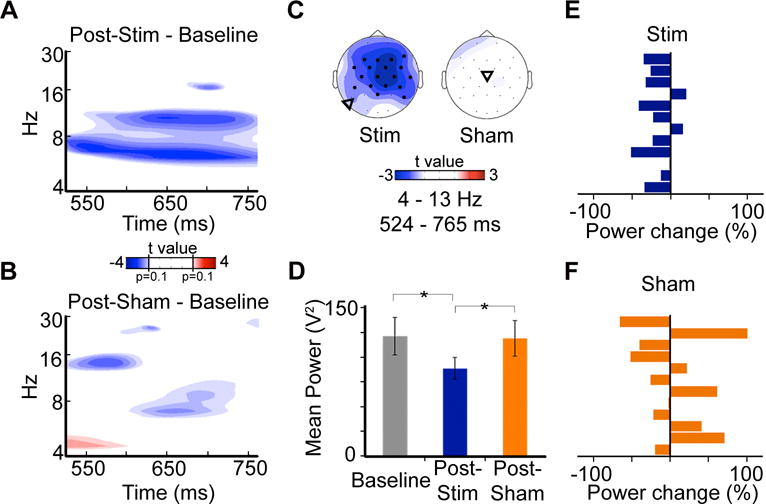

Based on fMRI-EEG evidence linking 4–13-Hz (theta-alpha) oscillatory EEG activity to fMRI connectivity of the retrosplenial cortex and hippocampus during recollection [8], we first tested the effect of stimulation on evoked oscillatory EEG power using this a priori frequency band of interest. We compared 4–13-Hz evoked oscillations for successfully recollected trials among Post-Stim, Post-Sham, and Baseline conditions. Cluster-based non-parametric simulation testing yielded significant frontoparietally distributed (Figure S2A) power reduction from 524–765ms for Post-Stim relative to Baseline (Figure 2ABC; cluster-corrected p=0.03). The same test for Post-Sham relative to Baseline identified no significant power differences (p>0.3). 4–13-Hz power averaged for all electrodes for the 524–765-ms period (Figure 2D) was significantly less Post-Stim compared to Baseline (t(11)=3.00, p=0.01, Cohen’s d=0.87) and compared to Post-Sham (t(11)=2.24, p=0.05, Cohen’s d=0.65), whereas the Post-Sham versus Baseline difference was not significant (t(11)=0.14, p=0.88). These reductions of theta-alpha power were consistent across subjects due to Stim (reductions in 10/12 participants; Sign Test p=0.039; Figure 2E), but not due to Sham (reductions in 7/12 participants; Sign Test p=0.774; Figure 2F). Further, an independent cluster-based non-parametric test for frequency across an a priori recollection latency interval [10], identified significant 6–11.5 Hz power reduction for Post-Stim versus Baseline (Figure S2B) and no significant differences for Post-Sham versus Baseline, consistent with the a priori frequency band used for primary analyses. Inter-trial theta-alpha phase coherence was reduced Post-Stim relative to Baseline and Post-Sham late in the epoch (Figure S2C), suggesting that sustained stimulus-evoked processing was reduced Post-Stim. Thus, stimulation-induced recollection precision improvement was associated with corresponding reductions in theta-alpha oscillatory activity.

Figure 2. Stimulation reduced evoked oscillatory correlates of successful recollection.

Plot indicates t values for pairwise comparisons of the time × frequency power spectra for A, Post-Stim and B, Post-Sham versus Baseline, averaged across electrodes and latency identified via cluster detection. The significant cluster of reduced power relative to Baseline is evident for Post-Stim but not Post-Sham. C. Topographical maps of t values demonstrate the frontal-central distribution of these effects. Electrodes identified via cluster detection are highlighted by bold markers. Triangles indicate approximate averaged stimulation locations for each condition. See also Figure S2. D. Mean 4–13-Hz averaged power for all electrodes was reduced for Post-Stim relative to both Baseline and Post-Sham. For each participant, mean 4–13-Hz power percent change is shown E, Post-Stim and F, Post-Sham, relative to baseline values. *p<0.05

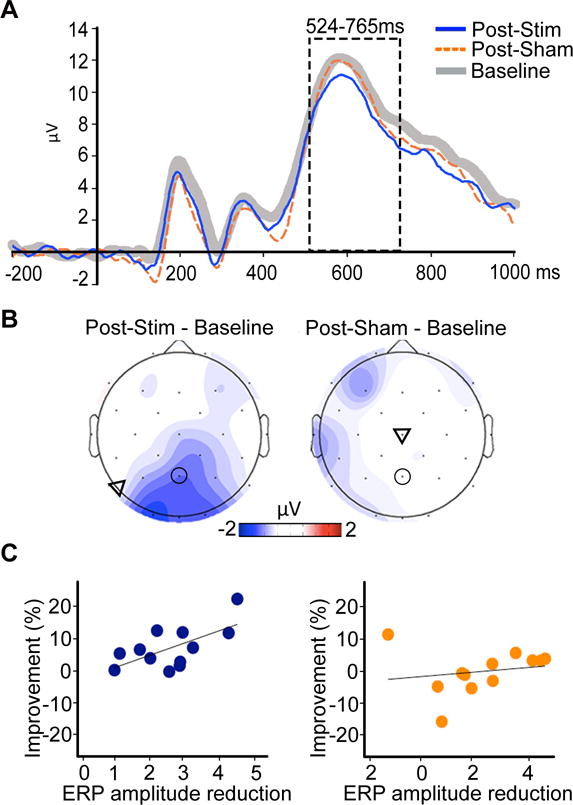

We next tested the effect of stimulation on event-related potential (ERP) correlates of successful recollection. Comparison of recollection success ERPs for both Post-Sham and Post-Stim yielded prototypical late-onset positive increases in amplitudes for successful recollected trials relative to guesses at parietal and occipital electrodes (known as the “parietal memory effect” [10]; Figure S3). This indicates reliable ERP correlates of successful memory irrespective of stimulation condition. For the 524–765ms latency interval of interest derived from cluster-based permutation testing, mean ERP amplitude for parietal-occipital electrodes was reduced Post-Stim relative to Baseline (t(11)=3.31, p<0.01; Cohen’s d=0.96) whereas Post-Sham amplitudes did not differ from Baseline (t(11)=0.86, p=0.41) (Figure 3AB). Further, correlation analyses using robust fitting to guard against outlier influences indicated that greater Post-Stim versus Baseline amplitude reduction was associated with greater recollection precision improvement (Robust-r=0.659, p=0.02) (Figure 3C). This relationship was not significant for Post-Sham (Robust-r=0.023, p=0.94). Stimulation thus reduced amplitudes of ERP correlates of recollection and these reductions corresponded to recollection precision improvements. As was the case for effects on recollection precision, theta-alpha power and mean ERP amplitudes were not significantly changed due to zero-intensity control stimulation in the additional control group (see Supplemental Experimental Procedures).

Figure 3. Stimulation reduced ERP correlates of successful recollection.

A. ERPs for Post-Stim (blue), Post-Sham (dashed-orange) and Baseline (thick gray) for one representative electrode (Pz). See also Figure S3. B. Topographical plot of the amplitude reduction relative to baseline show the posterior distribution characteristic of the parietal memory effect (the circled electrode is Pz). Triangles indicate approximate averaged stimulation locations for each condition. C. Relative to Baseline, greater reduction in ERP amplitude (Baseline – Post) was associated with greater percent-improvement in recall precision for Stim (blue) but not Sham (orange), tested using Robust correlation.

Discussion

Stimulation targeted to the HPM network improved precision, but not general success, of associative object-location memory. Notably, lesion-deficit and fMRI studies have implicated the human hippocampus [21–24] as well as parietal cortex [25, 26] in memory for precise details, suggesting that stimulation affected these HPM network locations. Indeed, changes in fMRI connectivity caused by the same stimulation parameters used here enhanced fMRI connectivity within the HPM network, particularly for hippocampus and medial aspects of parietal, occipital, and retrosplenial cortex [7]. Interestingly, just as fMRI connectivity enhancements with hippocampus were greater for medial regions than the lateral parietal regions that were stimulated [7], the changes in EEG/ERP correlates of recollection reported here occurred with medial distributions that were distal to the stimulation location (Figure 2, Figure 3). Collectively, this supports the interpretation that there were network-level effects of stimulation reflecting HPM-network involvement in memory precision.

In a previous study, HPM-network targeted stimulation improved paired-associate cued recall, also measured ~24 hours after the final stimulation session [7]. Cued recall is an “all-or-nothing” memory measure, and so differentiation of recollection precision from success was not possible. Relative to the previous cued recall testing, the current memory test involved substantially larger memory demands using a very different format (~100 random objects at precise locations within a redundant grid display versus ~20 face-word pairings in the previous study). Nonetheless, it is noteworthy that the effect sizes for stimulation on precision reported here (in a range typically classified as large) are similar to those obtained previously for cued recall [7]. The current findings provide novel information on the network basis of memory because they demonstrate the link between a highly specific aspect of memory, recollection precision, and the HPM network. Isolation of stimulation effects on precision from other co-occurring memory processes such as memory success within the same task is especially crucial for validating stimulation effects on memory and network-level processing, as condition-selective effects help mitigate influences from potential nonspecific factors such as history, practice, and placebo effects.

Stimulation targeted to the HPM network reduced amplitude of EEG correlates of recollection precision. This reduction is consistent with the hypothesis that successful retrieval of visual details corresponds to rapid memory reactivation [19, 27] and aligns with mounting evidence that reduced theta power correlates with better item-context memory [20]. One possibility is that stimulation promotes asynchronous activity within the medial temporal lobe and the neo-cortex, which produces the flexibility for higher resolution information storage and retrieval [27–31]. Increased EEG/ERP power and amplitude has been related to improved memory in many studies [9, 10, 17], and EEG/ERP oscillatory enhancements versus reductions may represent a neural distinction between general/semantic memory success and visuospatial memory precision. Memory for general information can benefit from verbal-semantic mnemonic strategies associated with the anterior hippocampal network, with heightened verbalization of recollection content during retrieval related to EEG/ERP increases. In contrast, the HPM network may support memory for precise perceptual details [3, 5] that does not benefit substantially from semantic strategies. This latter type of memory might be indicated by EEG/ERP decreases, as we observed due to stimulation in conjunction with enhanced memory for these perceptual details.

Evoked activity reductions may also indicate efficient processing. For example, evoked activity reductions can occur in conjunction with enhanced fMRI connectivity in experiments on priming [32], which is though to reflect heightened processing efficiency [33]. This pattern is consistent with our findings, in which stimulation enhanced HPM network fMRI connectivity [7] and reduced recollection-related evoked activity, specifically at frequencies characteristic of HPM network communication [34]. Although effects on memory precision were robust in the entire sample, our EEG/ERP subsample was relatively small. Nonetheless, several design features enhance confidence in reported neural findings, including strong a priori hypotheses on the particular neural signals that would be affected by stimulation, effects that significantly outlasted the stimulation sessions, as well as matched-intensity control (Sham) stimulation in addition to a separate zero-intensity, site-specific control group.

To summarize, our findings causally support hypothesized functional specialization of large-scale hippocampal-cortical networks. Although stronger tests of network functional subdivision could utilize control stimulation sites at varying levels of distance from the targeted network, our findings of stimulation-induced changes for a specific aspect of memory, recollection precision, extends previous lesion-based causal evidence for large-scale brain network involvement in cognition. That is, lesion-based accounts have necessarily focused on broad cognitive constructs, providing evidence for large-scale networks involved in language, attention, memory, and visuospatial processing [35], whereas the current findings demonstrate a causal role for a stimulation-responsive brain network and a highly specific neurocognitive construct. Finally, mechanisms by which brain stimulation affects cognition remain mysterious. There have been few demonstrations of stimulation effects on highly specific neural markers of well-defined cognitive processes [36], but in those studies effects did not outlast the period when stimulation was applied. The recollection precision improvements reported here outlasted the period of stimulation by ~24 h, consistent with our previous report of improvements lasting up to ~2 weeks after stimulation [37]. These long-lasting stimulation-induced changes included neural markers of detailed memory-content reactivation during recollection, thereby advancing understanding of how noninvasive brain stimulation could alter network function. Generation of long-lasting improvement in memory ability (rather than improved retention of specific material) has implications for the development of treatments for the many disorders related to hippocampal-cortical network dysfunction [15].

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Network-targeted stimulation caused lasting, selective increase in memory precision

Stimulation reduced evoked oscillatory neural correlates of recollection

The hippocampal posterior-medial network is causally involved in memory precision

Acknowledgments

We thank Anthony Ryals, Jane Wang, and Lynn Rogers for assistance with data collection and helpful discussion. Neuroimaging was performed at the Northwestern University Center for Translational Imaging, supported by Northwestern University Department of Radiology. This work was supported by P50-MH094263, R01-MH106512, and R01-MH111790 from the National Institute of Mental Health, T32-AG20506 from the National Institute on Aging, and F32-NS087885 from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Contributions

D.B. and J.V. designed the study. A.N., D.B., and E.G. collected the data. S.V. monitored stimulation-parameter and participant safety. A.N., D.B., and J.V. performed the analyses. All authors discussed the results and wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Battaglia FP, Benchenane K, Sirota A, Pennartz CM, Wiener SI. The hippocampus: Hub of brain network communication for memory. Trends Cogn Sci. 2011;15:310–318. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2011.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eichenbaum H. A cortical-hippocampal system for declarative memory. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2000;1:41–50. doi: 10.1038/35036213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ranganath C, Ritchey M. Two cortical systems for memory-guided behaviour. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:713–726. doi: 10.1038/nrn3338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fanselow MS, Dong HW. Are the dorsal and ventral hippocampus functionally distinct structures? Neuron. 2010;65:7–19. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.11.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nadel L, Hoscheidt S, Ryan LR. Spatial cognition and the hippocampus: the anterior-posterior axis. J Cogn Neurosci. 2013;25:22–28. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poppenk J, Evensmoen HR, Moscovitch M, Nadel L. Long-axis specialization of the human hippocampus. Trends Cogn Sci. 2013;17:230–240. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang JX, Rogers LM, Gross EZ, Ryals AJ, Dokucu ME, Brandstatt KL, Hermiller MS, Voss JL. Targeted enhancement of cortical-hippocampal brain networks and associative memory. Science. 2014;345:1054–1057. doi: 10.1126/science.1252900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herweg NA, Apitz T, Leicht G, Mulert C, Fuentemilla L, Bunzeck N. Theta-alpha oscillations bind the hippocampus, prefrontal cortex, and striatum during recollection: Evidence from simultaneous EEG-fMRI. J Neurosci. 2016;36:3579–3587. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3629-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klimesch W, Freunberger R, Sauseng P. Oscillatory mechanisms of process binding in memory. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010;34:1002–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rugg MD, Curran T. Event-related potentials and recognition memory. Trends Cogn Sci. 2007;11:251–257. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harlow IM, Yonelinas AP. Distinguishing between the success and precision of recollection. Memory. 2016;24:114–127. doi: 10.1080/09658211.2014.988162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kjelstrup KB, Solstad T, Brun VH, Hafting T, Leutgeb S, Witter MP, Moser EI, Moser MB. Finite scale of spatial representation in the hippocampus. Science. 2008;321:140–143. doi: 10.1126/science.1157086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kahn I, Andrews-Hanna JR, Vincent JL, Snyder AZ, Buckner RL. Distinct cortical anatomy linked to subregions of the medial temporal lobe revealed by intrinsic functional connectivity. J Neurophysiol. 2008;100:129–139. doi: 10.1152/jn.00077.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mesulam MM, Van Hoesen GW, Pandya DN, Geschwind N. Limbic and sensory connections of the inferior parietal lobule (area PG) in the rhesus monkey: a study with a new method for horseradish peroxidase histochemistry. Brain Res. 1977;136:393–414. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(77)90066-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buckner RL, Andrews-Hanna JR, Schacter DL. The brain’s default network: anatomy, function, and relevance to disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1124:1–38. doi: 10.1196/annals.1440.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bridge DJ, Paller KA. Neural correlates of reactivation and retrieval-induced distortion. J Neurosci. 2012;32:12144–12151. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1378-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rugg MD, Yonelinas AP. Human recognition memory: A cognitive neuroscience perspective. Trends Cogn Sci. 2003;7:313–319. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(03)00131-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mecklinger A, Johansson M, Parra M, Hanslmayr S. Source-retrieval requirements influence late ERP and EEG memory effects. Brain Res. 2007;1172:110–123. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.07.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gratton G, Corballis PM, Jain S. Hemispheric organization of visual memories. J Cogn Neurosci. 1997;9:92–104. doi: 10.1162/jocn.1997.9.1.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanslmayr S, Staresina BP, Bowman H. Oscillations and episodic memory: Addressing the synchronization/desynchronization conundrum. Trends Neurosci. 2016;39:16–25. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2015.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kolarik BS, Shahlaie K, Hassan A, Borders AA, Kaufman KC, Gurkoff G, Yonelinas AP, Ekstrom AD. Impairments in precision, rather than spatial strategy, characterize performance on the virtual Morris Water Maze: A case study. Neuropsychologia. 2016;80:90–101. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2015.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geib BR, Stanley ML, Wing EA, Laurienti PJ, Cabeza R. Hippocampal Contributions to the Large-Scale Episodic Memory Network Predict Vivid Visual Memories. Cereb Cortex. 2015 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhv272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koen JD, Borders AA, Petzold MT, Yonelinas AP. Visual short-term memory for high resolution associations is impaired in patients with medial temporal lobe damage. Hippocampus. 2016 doi: 10.1002/hipo.22682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yonelinas AP. The hippocampus supports high-resolution binding in the service of perception, working memory and long-term memory. Behav Brain Res. 2013;254:34–44. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2013.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berryhill ME, Phuong L, Picasso L, Cabeza R, Olson IR. Parietal lobe and episodic memory: bilateral damage causes impaired free recall of autobiographical memory. J Neurosci. 2007;27:14415–14423. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4163-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richter FR, Cooper RA, Bays PM, Simons JS. Distinct neural mechanisms underlie the success, precision, and vividness of episodic memory. Elife. 2016;5 doi: 10.7554/eLife.18260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Waldhauser GT, Braun V, Hanslmayr S. Episodic memory retrieval functionally relies on very rapid reactivation of sensory information. J Neurosci. 2016;36:251–260. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2101-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burke JF, Zaghloul KA, Jacobs J, Williams RB, Sperling MR, Sharan AD, Kahana MJ. Synchronous and asynchronous theta and gamma activity during episodic memory formation. J Neurosci. 2013;33:292–304. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2057-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greenberg JA, Burke JF, Haque R, Kahana MJ, Zaghloul KA. Decreases in theta and increases in high frequency activity underlie associative memory encoding. Neuroimage. 2015;114:257–263. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.03.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sederberg PB, Schulze-Bonhage A, Madsen JR, Bromfield EB, McCarthy DC, Brandt A, Tully MS, Kahana MJ. Hippocampal and neocortical gamma oscillations predict memory formation in humans. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17:1190–1196. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhl030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crespo-Garcia M, Zeiller M, Leupold C, Kreiselmeyer G, Rampp S, Hamer HM, Dalal SS. Slow-theta power decreases during item-place encoding predict spatial accuracy of subsequent context recall. Neuroimage. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buchel C, Coull JT, Friston KJ. The predictive value of changes in effective connectivity for human learning. Science. 1999;283:1538–1541. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5407.1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schacter DL, Wig GS, Stevens WD. Reductions in cortical activity during priming. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2007;17:171–176. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Foster BL, Kaveh A, Dastjerdi M, Miller KJ, Parvizi J. Human retrosplenial cortex displays transient theta phase locking with medial temporal cortex prior to activation during autobiographical memory retrieval. J Neurosci. 2013;33:10439–10446. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0513-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mesulam MM. From sensation to cognition. Brain. 1998;121:1013–1052. doi: 10.1093/brain/121.6.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reinhart RM, Woodman GF. Enhancing long-term memory with stimulation tunes visual attention in one trial. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:625–630. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1417259112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang JX, Voss JL. Long-lasting enhancements of memory and hippocampal-cortical functional connectivity following multiple-day targeted noninvasive stimulation. Hippocampus. 2015;25:877–883. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.