Abstract

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-associated optic neuropathy is rare with few reported cases, mostly involving immunocompetent patients who developed optic nerve involvement after infectious mononucleosis. We describe a unique case of a patient who developed severe bilateral EBV neuroretinitis after solid organ transplant.

Keywords: Epstein-Barr virus, optic neuropathy, immunosuppression, transplantation, neuroretinitis, case report

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is a ubiquitous DNA virus of the herpes family and is the primary agent of infectious mononucleosis. Although 90 to 95 percent of adults are EBV-seropositive, the majority of primary infections are subclinical. Ocular manifestations of EBV infection are diverse and include: dacryoadenitis, Parinaud oculoglandular syndrome, follicular conjunctivitis, stromal keratitis, anterior and posterior uveitis, choroioretinitis, optic neuritis, and ophthalmoplegia (1). Optic nerve involvement is particularly rare and has been documented primarily in immunocompetent patients after contracting mononucleosis (2-7). In solid organ transplant patients, EBV is most commonly associated with post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD), a potential fatal complication due to lymphoid proliferation in the setting of immunosuppression (8). We report an unique case of an adult patient who developed severe bilateral EBV neuroretinitis after lung transplantation from primary EBV infection of the central nervous system.

Case Report

A 57-year-old woman reported headache, malaise, and acute vision loss in her left eye. Past medical history was significant for systemic scleroderma leading to lung transplantation six years previously. Medications included prednisone (7.5 mg daily), sirolimus (1 mg daily), and prophylactic trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (1 double-strength tab three times weekly) and valganciclovir (450mg three times weekly). Social history was unremarkable. She was married and retired, and denied recent travel or sick contact.

On examination, the visual acuity (VA) was 20/20, right eye, and 20/400, left eye, with a left relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD). Intraocular pressure was 19 mmHg in both eyes. Extraocular movements were full in both eyes without pain on eye movement. Automated visual field testing revealed an enlarged blind spot in the right eye and dense generalized field loss in the left eye (Fig 1). The fundus examination was notable for bilateral disc edema with nerve fiber layer hemorrhages, more severe in the left eye. Given the history of lung transplantation and immunosuppression, a broad work-up was initiated which included inflammatory, infectious, PTLD, and toxic etiologies.

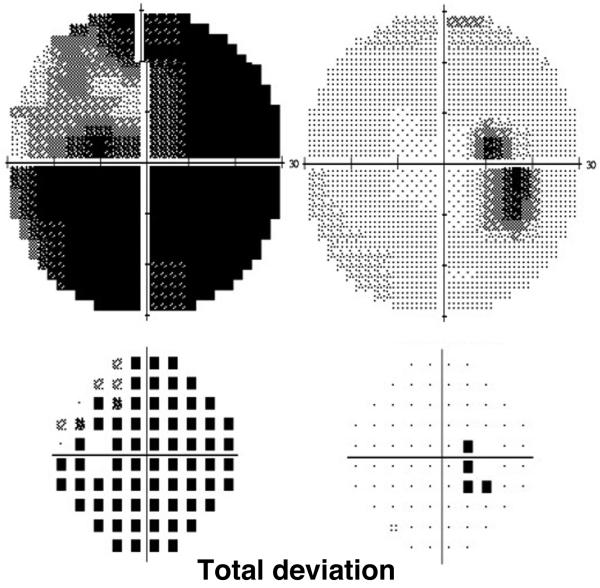

Figure 1.

Initial automated visual fields (Humphrey 30-2) shows an enlarged blind spot in the right eye and generalized field loss with sparing the superotemporal quadrant in the left eye.

Postcontrast orbital and brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed pachymeningeal enhancement, as well as enlargement of the retrobulbar left optic nerve and sheath with subtle nerve enhancement, but no infiltrative mass (Fig 2). Serum testing for Lyme disease, Bartonella species, Toxoplasma gondii, neuromyelitis optica, syphilis, and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody were negative. Random and trough level of sirolimus were within therapeutic range. Lumbar puncture revealed normal opening pressure and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis showed mild lymphocytic pleocytosis (11 WBC, 93% lymphocytes), protein of 67mg.dL (normal:15-45mg/dL), normal glucose, and negative cytology. With additional CSF studies pending, the patient’s vision stabilized for two weeks on empiric high-dose systemic corticosteroids (1 gram of intravenous methylprednisolone for 3 days followed by 60mg of oral prednisone for 11 days). However, one week after resuming her regular daily dose of prednisone (7.5mg), acuity in the right eye abruptly decreased to 20/150, dropping further to counting fingers (CF) at one foot within one week. Repeat visual field testing revealed new paracentral scotoma and supersonic field defect in the right eye (Fig 3). A RAPD was now detected in the right eye where the disc edema worsened with cystoid macular edema and subretinal fluid. In the left eye, there was stable vision with evolution of optic disc pallor and a partial macular star (Fig 4). Repeat brain MRI was stable and whole body positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) was unremarkable, arguing against PTLD.

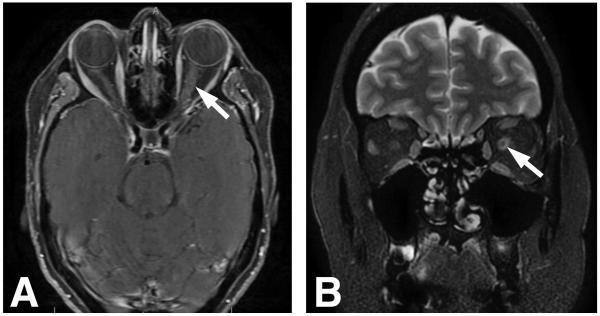

Figure 2.

A. Postcontrast axial T1 magnetic resonance imaging demonstrates left optic nerve enlargement and enhancement (arrow). B. Coronal T2 scan reveals expansion of the subarachnoid space surrounding the orbital segment of the left optic nerve (arrow).

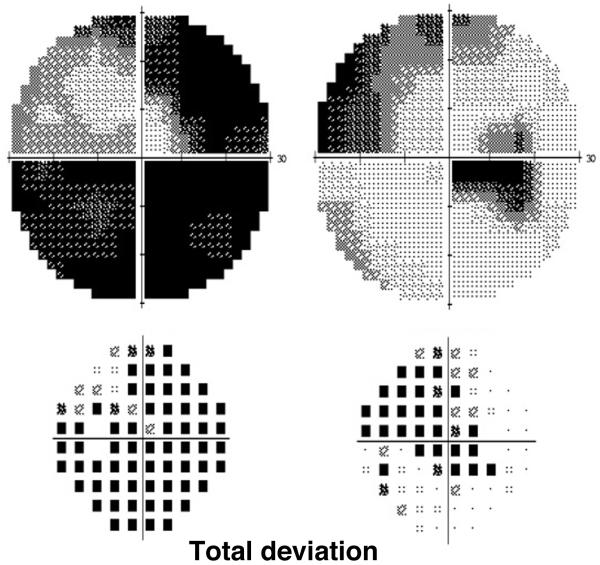

Figure 3.

Followup visual fields (Humphrey 30-2) demonstrate worse field loss in the right eye.

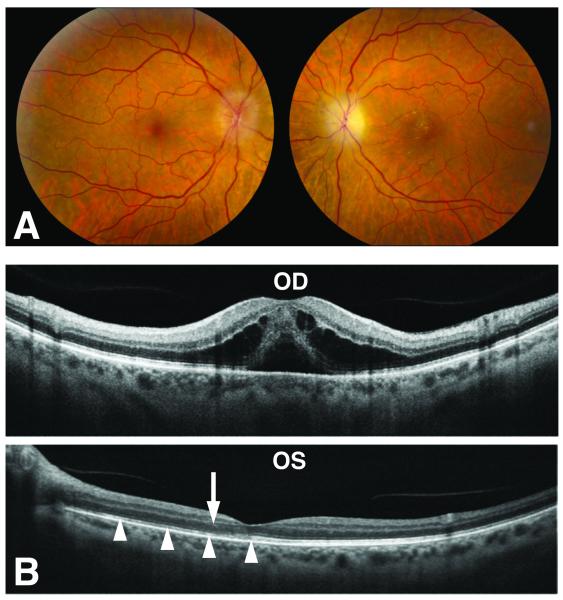

Figure 4.

A. There is diffuse optic disc edema in the right eye and resolving disc edema in the left eye with lipid deposition in the macula. B. Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography shows cystoid macular edema with subretinal fluid in the right eye (OD), while in the left eye (OS) there is disruption of the photoreceptor layer (arrowheads) near the fovea and lipid deposits (arrow) in the Henle Fiber layer.

CSF PCR analysis (Viracor IBT Laboratories, MO) from the initial work-up returned, showing 10,400 copies/mL of EBV DNA in the CSF but none in serum. Cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus, and varicella zoster virus DNA were all absent from the CSF and serum. Serum EBV immunoglobulins M and G, and Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen had been negative at the time of her lung transplant, and remain so to date. EBV DNA appeared in the serum at <1,000 copies/mL after the right eye lost central vision (real-time PCR using primers to a segment of LMP2 gene, UCSF Clinical Laboratories, limit of detection 1000 copies/mL). The patient was diagnosed with bilateral EBV neuroretinitis.

The patient was treated with six weeks of intravenous acyclovir and experienced modest improvement in vision in the left eye and resolution of her headache. She was transitioned to long-term oral valacyclovir at treatment dosage (3 grams daily). After initiating targeted therapy, CSF EBV titer gradually decreased from 10,400 to 6,500 (1 month), to 4,700 (2 months), to 2,600 (8 months), to 1,700 copies/mL (14 months). At 9 months after symptom onset, visual acuity was CF, right eye, and, 20/100, left eye. MRI showed resolution of the left optic nerve sheath enhancement.

Discussion

EBV-associated optic neuropathy is rare, seen mostly in immunocompetent adults in the setting of infectious mononucleosis (2-7). We evaluated an immunosuppressed patient who developed bilateral EBV neuroretinitis, with subacute swelling of the optic discs, accumulation of intraretinal and subretinal fluid originating from the disc leakage, and finally precipitation of lipid within the neurosensory retina once the fluid resorbed several weeks later (9). The thickening and enhancement of the left retrobulbar optic nerve seen on MRI here has been previously reported in the setting of neuroretinitis (10, 11). The absence of right optic nerve enhancement on repeat MRI could be explained by the course of high-dose steroids that the patient had just received, or a more localized involvement of the optic nerve head on the right compared to the left side.

In this post-transplant patient, the presence of EBV in the CSF raised immediate concern for PTLD. However, the patient’s imaging was not consistent with malignancy. Nonetheless, she is being serially monitored with neuroimaging as EBV optic neuritis may be a precursor for future development of PTLD (12). The patient was an EBV-seronegative recipient of bilateral lung transplants from a donor whose EBV status was unknown. EBV IgM and IgG titers were negative post-transplantation and upon admission, suggesting primary infection rather than reactivation. One prior report described EBV optic neuritis in a patient after solid organ transplant, but that case differed in that it was a pediatric patient who was EBV IgG seropositive prior to liver transplant (12).

It is notable that EBV DNA PCR was positive in CSF but not in the serum initially. This discrepancy between CSF and serum has been encountered previously in cases of EBV-associated PTLD, optic neuritis, and encephalitis (3, 13-15). Potential explanations include the use of two different PCR assays for CSF and serum samples, preferential replication of the virus in the CNS, or presence of PCR inhibitor in the peripheral blood.

The diagnosis of EBV neuroretinitis was strongly supported by a high CSF EBV titer and the resolution of systemic symptoms, stabilization of vision loss, and a decline in CSF EBV viral load upon initiation of high-dose acyclovir, all in the context of an otherwise unremarkable work-up. The required duration of oral antiviral treatment is unclear, although the patient’s slowly improving CSF EBV titers suggest a need for prolonged therapy in order to clear the infection. One important strategy for all opportunistic infections is to reduce immunosuppression whenever feasible, although that was not possible in this case. In contrast to our patient’s outcome, the prognosis of EBV optic neuropathy appears to be more favorable in immunocompetent patients, with nearly complete recovery achieved in most individuals without antiviral treatment (6, 7). It is noteworthy that clinical deterioration was slowed in our patient during a course of high-dose systemic steroids. We cannot fully exclude the possibility that an inflammatory neuroretinitis were caused by vasculitis related to the patient’s underlying scleroderma. However, this seems unlikely given the patient’s baseline immunosuppressed status. The steroid responsiveness was also consistent with a viral etiology.

Our case illustrates the need to consider EBV infection in the differential diagnosis among immunosuppressed individuals with atypical optic neuritis or neuroretinitis. As EBV optic nerve infection may present exclusively with CSF abnormalities, negative blood EBV DNA PCR tests do not necessarily rule out this cause. Prolonged systemic antiviral therapy that target herpes viruses should be considered, particularly in immunocompromised patients with EBV-associated optic neuropathy.

Acknowledgments

Financial support:

Dr. Levin is supported by EY023981 from the National Institutes of Health and a Career Development Award and departmental unrestricted support form Research to Prevent Blindness. Drs. Levin and Chin-Hong are both supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences and National Institutes of Health, through UCSF-CTSI Grant Number UL1 TR000004. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest disclosures:

No disclosure

Statement of Authorship

Category 1:

a. Conception and design

Yen Hsia, Marc Levin.

b. Acquisition of data

Yen Hsia, Marc Levin

c. Analysis and interpretation of data

Yen Hsia

Category 2:

a. Drafting the manuscript

Yen Hsia

b. Revising it for intellectual content

Marc Levin and Peter Ching-Hong

Category 3:

a. Final approval of the completed manuscript

Marc Levin

References

- 1.Matoba AY. Ocular disease associated with Epstein-Barr virus infection. Surv Ophthalmol. 1990;35:145–150. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(90)90069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Santos-Bueso E, Sáenz-Francés F, Méndez-Hernández C, Martínez-de-la-Casa JM, Garcia-Feijoo J, Gugundez-Fernandez JA, Garcia-Sanchez J. Papillitis due to Epstein-Barr virus infection in an adult patient. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. 2014;89:245–249. doi: 10.1016/j.oftal.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peponis VG, Chatziralli IP, Parikakis EA, Chaira N, Katzakis MC, Mitropoulos PG. Bilateral multifocal chorioretinitis and optic neuritis due to Epstein-Barr virus: a case report. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2012;3:327–332. doi: 10.1159/000343704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson MD, Kennedy CA, Lewis AW, Christensen GR. Retrobulbar neuritis complicating acute Epstein-Barr virus infection. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;18:799–801. doi: 10.1093/clinids/18.5.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corssmit EP, Leverstein-van Hall MA, Portegies P, Bakker P. Severe neurological complications in association with Epstein-Barr virus infection. J Neurovirol. 1997 Dec;3:460–464. doi: 10.3109/13550289709031193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones J, Gardner W, Newman T. Severe optic neuritis in infectious mononucleosis. Ann Emerg Med. 1988;17:361–364. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(88)80783-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Phowthongkum P, Phantumchinda K, Jutivorakool K, Suankratay C. Basal ganglia and brainstem encephalitis, optic neuritis, and radiculomyelitis in Epstein-Barr virus infection. J Infect. 2007 Mar;54:e141–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thorley-Lawson DA, Gross A. Persistence of the Epstein-Barr virus and the origins of associated lymphomas. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1328–1337. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra032015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Habot-Wilner Z, Zur D, Goldstein M, Goldenberg D, Shulman S, Kesler A, Giladi M, Neudorfer M. Macular findings on optical coherence tomography in cat-scratch disease neuroretinits. Eye. 2011;25:1064–1068. doi: 10.1038/eye.2011.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wals KT,MD, Ansari H, Kiss S, Langton K, Silver AJ, Odel JG. Simultaneous occurrence of neuroretinitis and optic perineuritis in a single eye. J Neuroophthalmol. 2003;23:24–27. doi: 10.1097/00041327-200303000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vaphiades MS, Wington EH, Ameri H, Lee AG. Neuroretinitis with retrobulbar involvement. J Neuroophthalmol. 2011;31:12–15. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0b013e3181e7e4c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu BR, Fenton LZ, O'Connor J, Narkewicz MR. Epstein-Barr virus related optic neuritis as a precursor to the development of post transplant lymphoproliferative disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;49:243–245. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31817e6f95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shimizu H, Saitoh T, Koya H, Yuzuriha A, Hoshino T, Hatsumi N, Takada S, Nagaki T, Nojima Y, Sakura T. Discrepancy in EBV-DNA load between peripheral blood and cerebrospinal fluid in a patient with isolated CNS post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder. Int J Hematol. 2011;94:495–498. doi: 10.1007/s12185-011-0951-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kittan NA, Beier F, Kurz K, Niller HH, Egger L, Jilg W, Andreesen R, Holler E, Hildebrandt GC. Isolated cerebral manifestation of Epstein-Barr virus-associated post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder afterallogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a case of clinical and diagnostic challenges. Transpl Infect Dis. 2011;13:524–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2011.00621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Babik JM, Katrak S, Miller S, Shah M, Chin-Hong P. Epstein-Barr virus encephalitis in renal transplant recipient manifesting as hemorrhagic, ring-enhancing mass lesions. Transpl Infect Dis. 2015;17:744–750. doi: 10.1111/tid.12431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]