Abstract

The role of hemoglobin (Hb) redox forms in tissue and organ toxicities remain ambiguous despite the well-documented contribution of Hb redox reactivity to cellular and subcellular oxidative changes. Moreover, several recent studies, in which Hb toxicity were investigated, have shown conflicting outcomes. Uncertainties over the potential role of these species may in part be due to the protein preparation method of choice, the use of published extinction coefficients and the lack of suitable controls for Hb oxidation and heme loss. Highly purified and well characterized redox forms of human Hb were used in this study and the extinction coefficients of each Hb species (ferrous/oxy, ferric/met and ferryl) were determined. A new set of equations were established to improve accuracy in determining the transient ferryl Hb species. Additionally, heme concentrations in solutions and in human plasma were determined using a novel reversed phase HPLC method in conjugation with our photometric measurements. The use of more accurate redox-specific extinction coefficients and method calculations will be an invaluable tool for both in vitro and in vivo experiments aimed at determining the role of Hb-mediated vascular pathology in hemolytic anemias and when Hb is used as oxygen therapeutics.

Keywords: hemoglobin, extinction coefficients, spectrometric, HPLC measurements

1. Introduction

The concentration of acellular Hb in circulation increases after excessive hemolysis in malaria, sickle cell disease, blood transfusion, and after infusion of Hb-based oxygen carriers. It is becoming increasingly evident that heme loss after Hb oxidation plays a significant role in the toxicity associated with acellular Hb [1–4]. Superoxide ions (O2˙−) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) formed during the autooxidation of Hb drive a catalytic cycle that oxidizes ferrous (HbFe2+) into ferric (met) (Hb Fe3+), ferryl (HbFe4+), and the ferryl radical (·HbFe4+) [5, 6]. The catalytic cycle known as the pseudoperoxidase reaction is represented by equations 1 to 3. Rapid formation of the ferryl can occur when the reaction begins with ferrous Hb with excess H2O2 (Eq.1). The ferryl species autoreduces to ferric iron (Fe3+) (Eq.2) and in the presence of additional H2O2, ferryl iron (Fe4+) is regenerated back. When H2O2 reacts with the ferric form of Hb, a protein radical (·HbFe4+=O) is also formed (Eq.3).

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

These oxidatively unstable Hb intermediates (ferryl/ferryl protein radicals) oxidize residues within the Hb globin chains (and within other proteins in proximity), ultimately leading to Hb degradation and heme loss [6–8]. Our recent study in a transgenic sickle cell disease (SCD) mouse model showed that heme derived from sickle red blood cell (RBCs) hemolysis acts as a damage-associated molecular pattern molecule (DAMP) [4]. This correlates with another study indicating that haptoglobin (Hp) and hemopexin (Hpx) both attenuated Hb-induced vascular, cardiac, and renal injury after infusion of free Hb (and infusion of aged RBCs) in dogs, guinea pigs, and the SCD mouse model by controlling these redox side reactions [9–11] and by preventing extravasation of Hb through the vascular walls [4].

Mechanistic studies aimed at investigating Hb toxicity in cell culture experiments have shown, however, conflicting outcomes as to the precise contribution of Hb oxidation states to the observed cytotoxicity [11]. These investigations have also revealed that Hb toxicity depends on the cell type, exposure duration, and more importantly, the precise nature of heme/iron redox states used in these experiments [2]. Because Hb spontaneously undergoes autooxidation (Fe2+→Fe3+) and autoreduction (Fe4+→Fe3+), controlling Hb redox transitions is a critical element in the validity of these studies. Another confounding factor in these experiments is the purity of Hb preparations. Chromatographically purified stroma-free Hb (SFH) (derived from hemolysate) preparations were used in several of these studies [12, 13]. Unfortunately, some SFH preparations were contaminated with RBC enzymes, such as superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase which invariably complicated the interpretation of Hb redox reactions in vitro or in cell culture media [3].

In spite of the variability in purity of these preparations (i.e., whether Hb is obtained from human, animal sources, or whether or not Hb is chemically or genetically modified) the same set of published extinction coefficients were used in these studies [14–16]. Examples of the most frequently cited published molar extinction coefficients values for deoxy Hb, oxy Hb, carboxy Hb (HbCO) and ferric Hb forms (based on absorbance measurements at 540, 560, 576, and 630 nm) were those reported by Benesch et al [17]. Hb concentrations were determined by conversion of Hb to Hb cyanide derivative using the extinction coefficient (ε540nm = 11.5 mM−1cm−1) [17]. This value was originally published by Drabkin [18] and was later adopted after minor modification (ε540nm = 11.0 mM−1cm−1) by the International Committee for Standardization in Haematology (ICSH) [19, 20, 43–45]. Hb ferric and ferryl redox extinction coefficients were originally reported by Winterbourn [21]. In their work, Winterbourn et al., took special precaution to eliminate RBC enzyme contamination from the Hb preparations. In addition, contribution of hemichromes, choleglobin as well as ferryl Hb species in these solutions were taken into account and subtracted (in the case of hemichromes, choleglobin) from the overall Hb spectrum under an oxidant-generating system. Extinction coefficients (ε560nm 14.1, ε577nm 3.9, ε630nm 3.0 mM−1cm−1) determined previously for myoglobin (Mb) by Wintburn [22] were also used to calculate both ferryl Hb/Mb solutions.

Several decades have passed since the work by Benesch and Winterbourn [17, 21] in which equations for determining deoxyHb, ferrous Hb, and ferric Hb levels were first reported. With the advancement in analytical tools and the availability of high resolution spectrophotometric analysis, we revisited these early determinations using highly purified redox forms of Hb. In this study, HbA solutions were first purified using anion exchange followed by cation exchange chromatography. Afterward, the extinction coefficient of deoxyHb, ferrous Hb, and ferric Hb in PBS were determined and compared with those generated by early methods. A novel and more accurate RP-HPLC method, for testing Hb concentrations in plasma was also developed.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals

Potassium ferricyanide, Drabkin reagent, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) (30% w/w) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louise, Missouri, US). Poly-t-dimethylsiloxane (the anti-foaming reagent) was purchased from TSC Sci Corp.

2.2. Preparation of various hemoglobin solutions

Blood was obtained from normal and SCD patients attending the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland with informed consent. Hb was purified from human erythrocyte lysates by anion DEAE and cation CM chromatography respectively [23]. Briefly, red blood cells were washed three times with PBS and centrifuged at 500 g for 20 minutes using a Legend X1R centrifuge (Thermo Scientific). The precipitate was diluted with 3 fold volumes of water and mixed gently with a glass rod at room temperature for 30 min. Final salt concentration was adjusted to about 0.9% with NaCl. The lysate was then centrifuged at 12,000 g for 40 mins. The supernatant was filtered with 0.2 µM membranes, and then dialyzed against 50 mM Tris-acetate buffer, pH 8.3, at 4°C.

2.3. Purification of HbA

The lysate was loaded onto a DEAE Sepharose Fast Flow column (Bed dimentions 26 × 100 mm, 53 mL), which was equilibrated with 6 column volumes of 50 mM Tris-acetate at pH 8.3 (buffer A) using an AKTA FPLC System. HbA was eluted at 4°C with a linear gradient of 25–100% buffer B, 50 mM Tris-acetate at pH 7.0 in 12 column volumes. The column was eluted at a flow rate of 2 ml/min and the effluent was monitored at 540 and 630 nm. HbA was collected, concentrated, and then dialyzed against extensive 10 mM phosphate buffer (buffer C), pH 6.5, at 4°C. HbA solution was then applied to a CM Sepharose Fast Flow column (Bed dimentions 26 × 100 mm, 53 mL), which was equilibrated with 6 column volumes of buffer C using an AKTA FPLC system. HbA was eluted (at 4°C) with a linear gradient of 0–100% buffer D, 15 mM phosphate buffer (at pH 8.5) in 12 column volume (2 mL/min) and the effluent was monitored at 540 and 630 nm. HbA was collected, concentrated, dialyzed against PBS, and was stored at −80°C for future use. The complete removal of antioxidative enzymes, namely SOD and catalase in the purified HbA solution was verified as previously reported [24]. Molar concentrations for all Hb solutions in this paper are based on heme. Purified HbA in PBS solutions was then dialyzed against water for 12 hours at 4°C. The dialyzing process was repeated twice with fresh cold water. The pure HbA was completely dried into powder using a FreeZone Freeze Dry System (Labconco Corp, MO, USA).

2.4. Preparation of ferric hemoglobin

The ferric (met) Hb was generated as previously reported [25] by incubating 2 mM ferrous (oxy) Hb with 3 mM potassium ferricyanide in PBS at room temperature for 15 mins. Excess ferro- and ferricyanide were removed by passing the reaction solution through a Sephadex G-25 column equilibrated with PBS at 4°C.

2.5. Preparation of deoxy hemoglobin

The deoxyHb was prepared by bubbling nitrogen into an HbA (oxy) solution (60 µM) containing 0.01% poly-t-dimethylsiloxane (0.01% anti-foaming reagent) at room temperature for 20 minutes. DeoxyHb formation and purity were confirmed by spectral scanning using an Agilent 8453 spectrophotometer. The deoxygenation process was regarded as complete when the shoulder peak at 576 nm is completely diminished [26].

2.6. Preparation of ferryl hemoglobin

Ferryl Hb solutions were prepared as previously reported [2, 3] by mixing 20 times the concentration of metHb (60 µM) with H2O2 (1200 µM) in PBS buffer at room temperature for 1 minute. Afterward, 12 units of catalase were added into the reaction to terminate the action of H2O2 (see Results and Discussion).

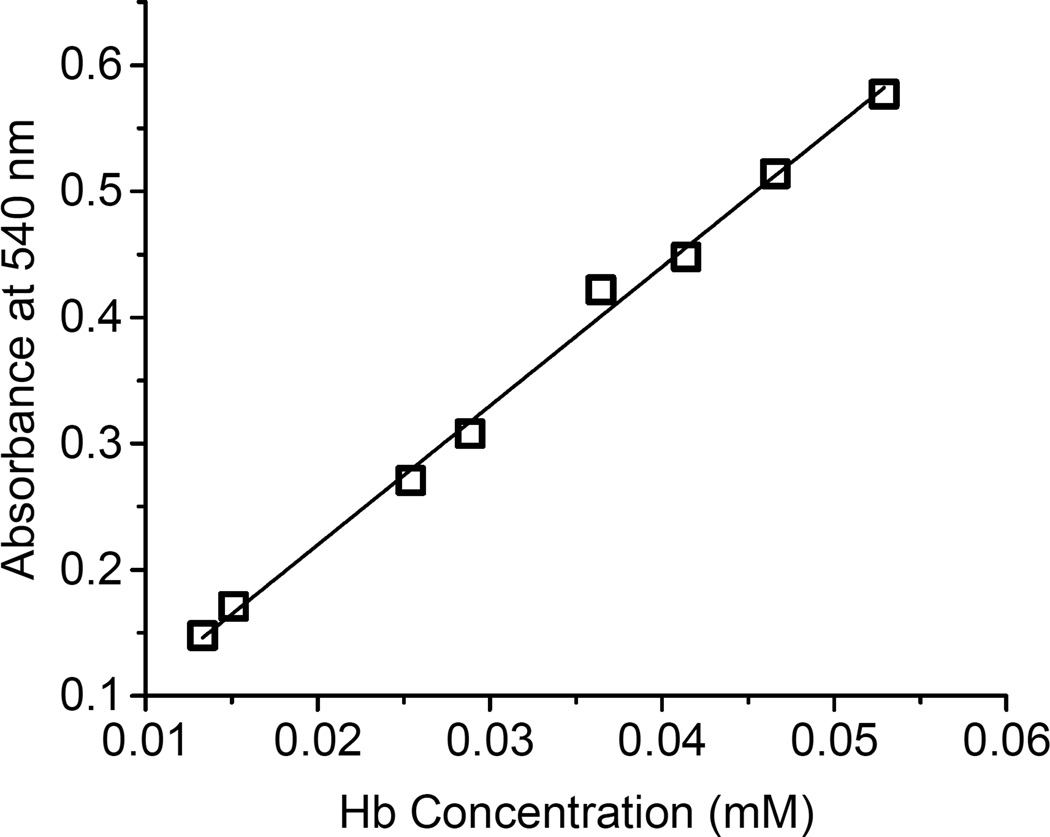

2.7. Standard calibration curve for hemoglobin determinations

Drabkin’s Reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, Catalogue# D5941) was used to construct Hb standard curves using 0.05, 0.1, 0.15, and 0.2 mL of HbA standards (HbA-st1 and HbA-st2) mixed with 1 mL of Drabkin’s working reagent and incubated at room temperature for 15 minutes. Absorbances at 540 nm were recorded and the calibration curve was constructed against the final cyanometHb concentrations. Test Hb solution concentrations were determined directly from the calibration curve (see Fig. 1).

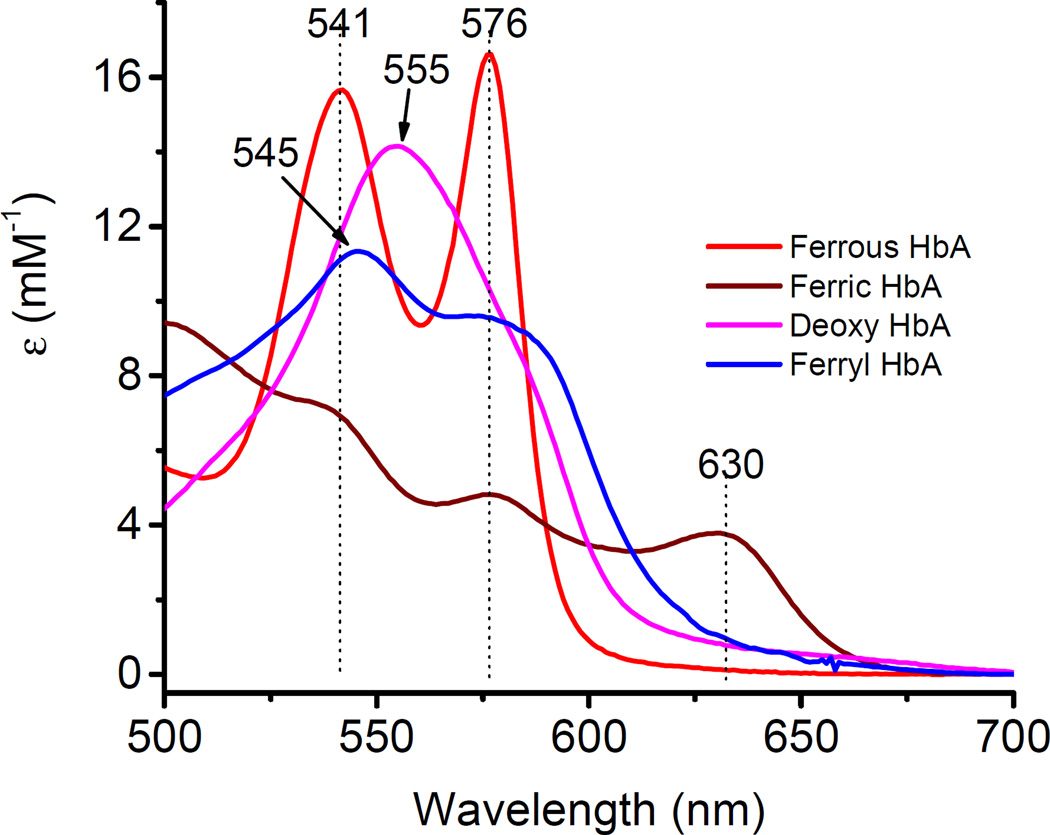

Fig. 1.

Representative spectra of hemoglobin’s main redox forms. A spectral scan from 500 to 700 nm captures the different oxidation states of hemoglobin identified by characteristic peaks in the visible region (ferrous, 541 and 576 nm; deoxy, 555 nm; ferric, 500 and 630 nm; ferryl, 545 nm, 576 nm, and a flattened region between 600 and 700 nm) in PBS at 25°C. AU is arbitrary units.

2.8. Kinetic time courses of ferryl hemoglobin formation

Ferric Hb (60 µM) was mixed with increasing amounts of H2O2 (0–2400 µM) in PBS in the spectrophotometer to capture the reaction spectrum and was monitored between 500–700nm, every 20 seconds for 30 minutes using an Agilent 8453 spectrophotometer.

2.9. Stopped-flow rapid mixing spectrophotometric analysis

To capture the newly formed ferryl species when H2O2 was added to Hb solutions, we used rapid mixing stopped-flow apparatus. This stopped-flow technique requires very small reactant volumes and allows evaluation of ferryl Hb formation and decay-based kinetics on millisecond timescales. The reactions of the ferrous and ferric forms of Hbs (60 µM) with excess amount of H2O2 (1200 µM) were measured in an Applied Photophysics SF-17 microvolume stopped-flow spectrophotometer in PBS at room temperature as previously reported [27, 28]. Spectra were captured as a function of time using an Applied Photophysics photodiode array accessory. Spectral data were then subjected to global analysis and curve fitting routines included in the Applied Photophysics software. The spectra of major reaction species were reconstructed, and the reaction rate constants were calculated.

2.10. Reverse phase high performance liquid chromatograph (RP-HPLC)

RP-HPLC was performed using a Zorbax 300SB-C3 column (4.6×250 mm, 5 µm, 300 Å pores) [29]. Hb samples (20 µg) dissolved in 25 µL water or 0.4 mM of potassium ferricyanide solution were loaded on a C3 column equilibrated with 35% acetonitrile containing 0.1% TFA. The step gradient was initially set at 35% acetonitrile, for 10 min, and then increased to 37% acetonitrile over 5 min. The gradient was increased to 40% acetonitrile over 1 min and then to 43% acetonitrile over 10 min. The column was washed by 100% acetonitrile for 8 minutes, and then equilibrated with 35% acetonitrile for 16 minutes before injection of the next sample. The flow rate was 1 mL/min at 25°C. The eluent was monitored at 280 nm (globin chains and heme) and 405 nm (heme) for 30 minutes. The gradient profile controlled by the HPLC pump in developing the column lasts for 26 minutes. However, the gradient developers (buffers A and B) require additional 4 minutes to clear the (4ml) column resulting therefore in a total of 30 minute elution time profile as shown in Figures 5 and 6.

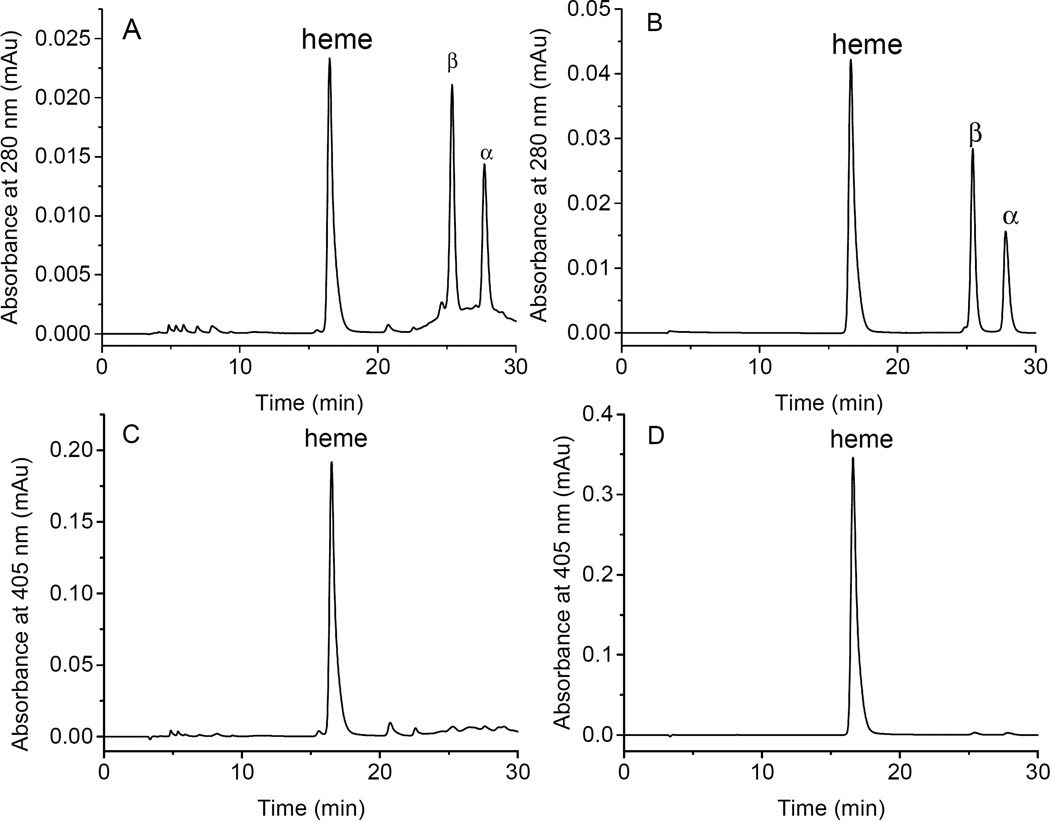

Fig. 5.

Reversed phase HPLC analyses of oxy HbA and metHbA samples. RP-HPLC was performed using a Zorbax 300 SB C3 column (4.6×250 mm). Hb samples (20 µg) in 25 µL of PBS (A, C) or 0.4 mM of Potassium ferricyanide (B, D) were loaded on the C3 column equilibrated with 35% acetonitrile containing 0.1% TFA. The gradient was initially set at 35% acetonitrile, for 10 min, and then increased to 37% acetonitrile over 5 min. The gradient was increased to 40% acetonitrile over 1 min and then to 43% acetonitrile over 10 min. The flow rate was 1 mL/min at 25°C. The eluent was monitored at 280 nm (A, B; for globin chains) and 405 nm (C, D; for heme).

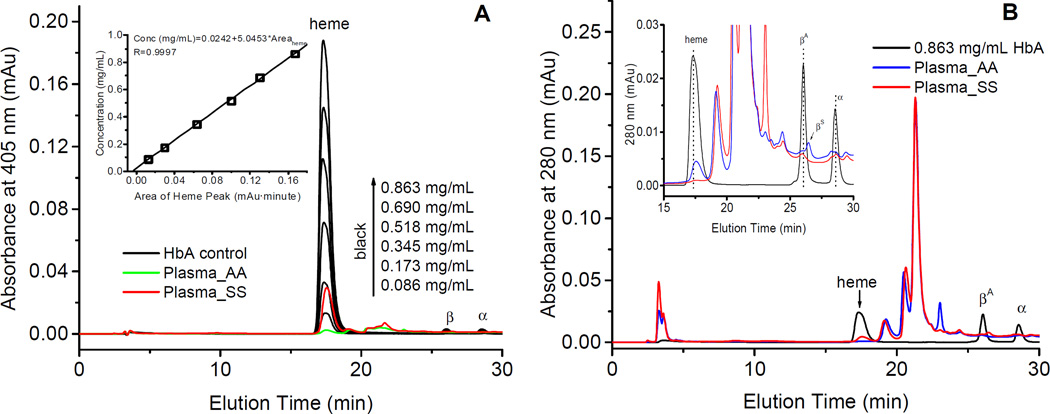

Fig. 6.

Reversed-HPLC analyses of free hemoglobin and heme in human plasma samples. A) RP-HPLC heme absorption peaks (monitored at 405 nm) for the HbA control at different concentrations (ranging from 0.086 mg/mL to 0.863 mg/mL) (black curves) and absorption peaks obtained from unknown samples obtained normal plasma (blue curve) and plasma from SCD patients (red curve) respectively and after mixing these samples with 0.4 mM of potassium ferricyanide for the complete oxidation heme iron; The area under the curve (AUC) for of heme peaks were integrated using Origin 6.0 software. The relationship between the heme peak areas and a wide range of Hb concentrations is displayed in the inset. B) RP-HPLC plots (monitored at 280 nm) of HbA control (black curve) and plasma obtained from normal individuals (blue curve) and SCD patients (red curve). The insert in this figure capture a narrower view, between 15–30 mins.

2.11. Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopic studies

Hb spectra were recorded in a JASCO-815 spectrometer (Tokyo, Japan) at 25°C using a 0.1 cm light path cuvette (200 µL) as described previously [30]. The Hb concentration was 5.2 µM in heme for measurement at the far UV-CD range from 200 to 250 nm. All experiments were carried out in PBS buffers.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Spectral characterization of hemoglobin redox states

A typical UV-visible absorbance spectroscopy of the main redox states of Hb is shown in Fig. 1. In the visible region of Hb absorption spectrum, the ferrous/oxy Hb (red) spectrum is characterized by two major absorption peaks (namely β and α bands) at 541 nm and 576 nm respectively [46, 47]. The spectrum of deoxyHb with its characteristic single peak (555nm) in the visible region is shown in purple color [26]. The spectrum of oxidized Hb (ferric Hb) (brown) shows 3 major peaks at 541, 576, and 630 nm respectively. The spectrum of ferryl Hb (blue) in the visible region is characterized by two peaks at 545 nm and 576 nm and a flattened region between 600–700 nm. To confirm the redox identity of the ferryl state intermediate, sodium sulfite (Na2S)was added to convert the ferryl to a metastable sulfHb intermediate which absorbs very strongly at 620 nm [2, 31] (data not shown). The spectra of hemichromes and low spin forms of ferric Hb induced by different effects (pH, detergent, heat) are not included. The hemichrome spectrum can be distinguished from that of the ferryl and its contribution to the absorption at the 700nm wavelength can be determined [32].

3.2. Standard solutions for deoxy, ferric and ferryl hemoglobins

Two HbA standard solutions were prepared by weighing 45.0 mg and 51.1 mg of the lyophilized HbA powder that were dissolved into 10 mL of the PBS. The final concentrations of the HbA standard solution 1 (HbA-st1) and standard solution 2 (HbA-st2) were 4.50 and 5.11 mg/mL (0.280 and 0.319 mM), respectively. The two standard HbA solutions were mixed with Drabkin’s reagent to make final Hb concentrations ranging between 0.01–0.06 mM, and absorbances at 540 nm were recorded to construct the standard curve represented in Fig. 2. The slope of the fitted line was 11.02 in agreement with the extinction coefficient for cyanometHb at 540 nm which was reported to be 11.0 mM−1cm−1 [19, 20, 43–45]. This standard curve was used throughout this study for the determination of deoxy/ferrous, ferric, deoxy, and ferryl HbA concentrations.

Fig. 2.

Calibration curve for the Drabkin method used for the measurement of hemoglobin concentrations. A wide range of volumes (0.05, 0.1, 0.15, and 0.2 mL) of HbA standards (HbA-st1 and HbA-st2) were mixed with 1 mL of Drabkin’s working reagent and were incubated at room temperature for 15 minutes. The absorbances at 540 nm were recorded and the calibration curve was constructed against the final cyanometHb concentrations.

3.3. Oxidation of ferric hemoglobin by peroxide and the generation of the ferryl state

Adding H2O2 into ferric Hb solution, Fe3+ iron oxidizes to Fe4+ (ferryl Hb) [33, 34]. However, the ferryl Hb is not stable, and the Fe4+ reverts rapidly back to Fe3+ in PBS at room temperature [3, 6, 8]. It is, therefore, difficult to obtain an absolutely pure ferryl Hb in PBS at room temperature. We were able however to convert more than 95% of the heme to the ferryl form (see Materials and Methods), considerably higher than one recently reported attempt to prepare the ferryl heme (~80%) in the literature [35].

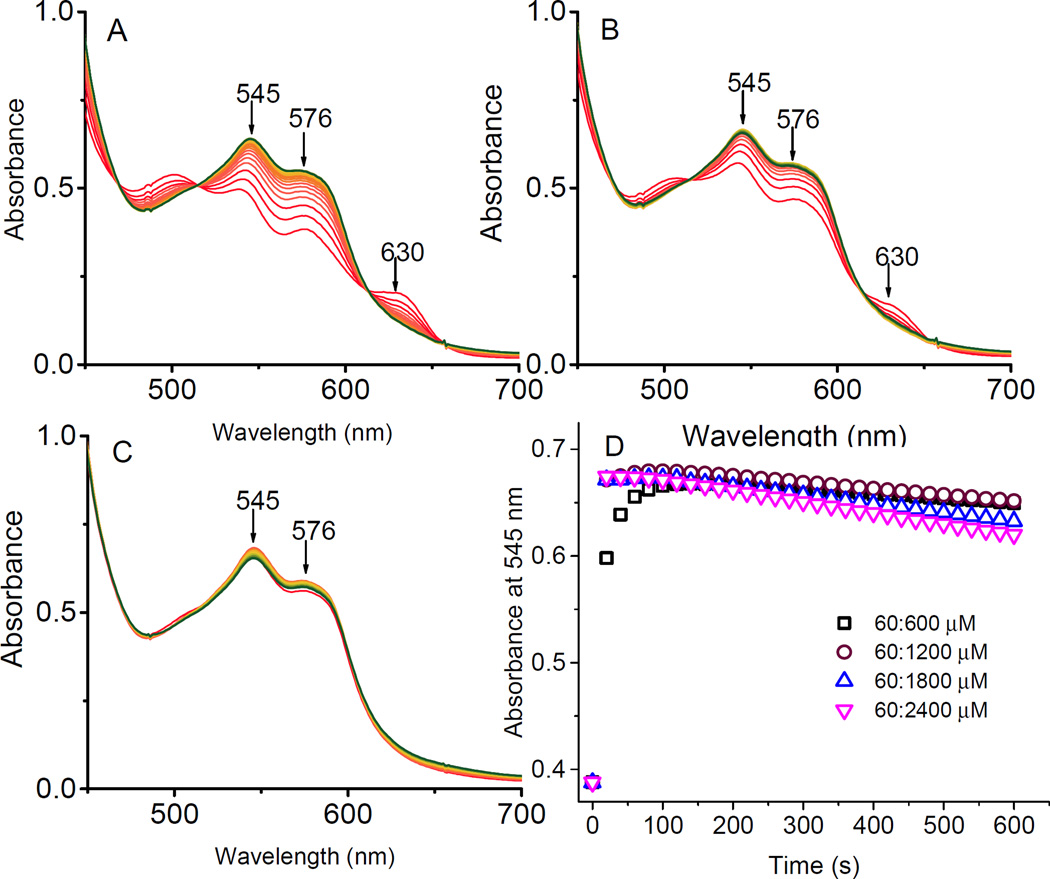

Fig. 3 shows spectral changes during the conversion of 60 µM metHb to the ferryl form using increasing concentration of H2O2 at the following heme to H2O2 ratios: 60:120, 60:300, and 60:1200 µM. The spectra were monitored every 20 seconds for 10 mins. At higher H2O2 concentrations we were able to convert metHb to ferryl Hb to nearly 100% (>95%) with little or no heme bleaching effects as there was little or no changes at the at the 700nm wavelength (Fig. 3A, 3B, and 3C). Importantly, the unavoidable autoreduction of ferryl Hb back to ferric Hb was also minimized at these higher concentration of H2O2 [3]. Time courses for absorbance changes at 545 nm as a function of time are shown in Fig. 3D. As can be seen in this Figure, ferryl Hb formation was achieved in the first 1–2 minutes as 1200 µM of H2O2 mixing with 60 µM of metHb (brown circle). For the calculation of the extinction coefficient for ferryl HbA reported in Table 1, we used the highest heme: H2O2 ratio (i.e., 60:1200 µM), in the first 80 seconds of the reaction.

Fig. 3.

Kinetic time courses of the reaction between ferric hemoglobin with peroxide. The reaction was carried out as a function of time in PBS at room temperature using increasing concentrations of H2O2 over heme (A) 60:120 µM, (B) 60:240 µM, and (C) 60:1200 µM. The spectra were scanned every 20s for 600 s (red) and the last recorded spectra (green) represent the end of reaction in each experiment. (D) Time courses of the reactions of ferric HbA with H2O2 (60: 600, 1200, 1800, and 2400 µM) in PBS at room temperature, monitored at 545 nm.

Table 1.

Extinction coefficients of ferrous and ferric HbA compared with other reported values.

| Wave length (nm) |

Millimolar extinction coefficient (mM−1) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| This work | Antonini[26] | Winterbourn[21] | Benesch[17] | Herold[35] | ||

| Ferrous Hb | 415 | 141.2 | 128 | |||

| 540/541 | 15.54 | 13.8(541nm) | 15.3 | |||

| 560 | 9.35 | 8.6 | 9.06 | |||

| 576/577 | 16.61 | 14.6(577 nm) | 15.0(577 nm) | 16.5 | ||

| 630 | 0.131 | 0.17 | 0.15 | |||

| Ferric Hb | 405 | 167.0 | 179.0 | |||

| 500 | 9.40 | 10.0 | ||||

| 540/541 | 7.05 | 6.82 | ||||

| 560 | 4.64 | 4.30 | 4.50 | |||

| 576/577 | 4.81 | 4.45 | 4.65 | |||

| 630 | 3.78 | 4.40 | 3.36 | 3.80 | ||

| Deoxy Hb | 540/541 | 11.60 | 10.8 | |||

| 560 | 13.80 | 13.4 | ||||

| 576/577 | 10.44 | 10.1 | ||||

| 630 | 0.82 | 1.15 | ||||

| Ferryl Hb | 418 | 113.40 | 100.0 | |||

| 541/544 | 11.07 | 11.0(544nm) | ||||

| 576/574 | 9.56 | 10.0(574 nm) | ||||

| 630 | 1.07 | |||||

[17] Benesch RE, Benesch R, Yung S. Anal Biochem. 1973; 55(1):245-8.

[21] Winterbourn CC. Methods Enzymol. 1990; 186: 265-72.

[26] Antonini E, Brunori M. In Hemoglobin and Myoglobin in their Reactions with Ligands. Amsterdam: North-Holland;1971.

[35] Herold S, Rehmann FJ. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;34(5):531-45.

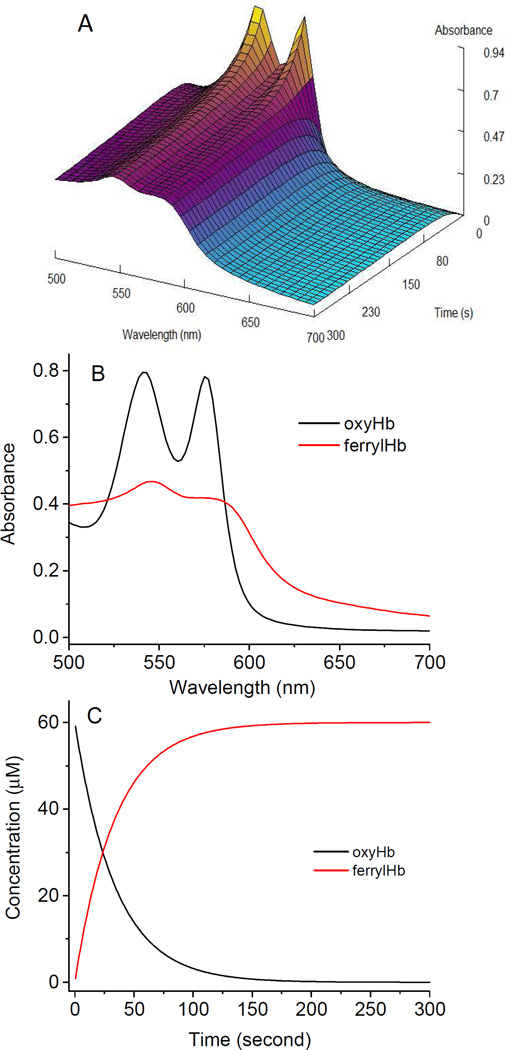

We carried our rapid mixing experiments to capture the early phase of ferryl Hb formation starting with either ferrous or ferric Hb, and the spectra were recoded using a diode array function in the stopped flow apparatus. Fig. 4 shows a typical data set of the global fitting routine used to calculate and re-construct spectra representing the main reaction intermediates when 60 µM ferrous Hb was mixed with 1200 µm H2O2 in the stopped-flow (Fig. 4A). Using Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) software, two spectral intermediates were then reconstructed, the first intermediate is that of Fe2+ and the second being that of the Fe4+. A single exponential process was monitored at all wavelengths essentially describing the transition from the Fe2+ to Fe4+ with a calculated rate constant (k =0.0275s−1) for the ferryl Hb formation (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Stopped flow spectrophotometric analyses of reaction of ferrous hemoglobin with peroxide. A) Three dimensional spectral changes during the oxidation of ferrous Hb (60 µM) by H2O2 (1200 µM). Spectra were collected every 0.5 seconds for 5 minutes in PBS, pH 7.4. The oxidation of ferrous Hb occurs immediately as evidence by the loss of absorption at the 576 and 541 nm bands that are typical of oxyferrous hemoglobin, yielding a final spectrum of a ferryl intermediate as can be seen by the appearance of the spectrum with peaks at 545 and 576 nm. B) Singular value decomposion (SVD) program was used to reconstruct the main spectral intermediate, namely ferrous and ferryl. C) Fractional changes of oxy/ferrous Hb and ferryl Hb during the oxidation of Hb with H2O2 (black, and red, respectively).

CD spectroscopy was used to investigate the effect of H2O2 on the secondary structure of Hb. The CD spectrum of ferric Hb control (in the absence of H2O2) showed two characteristic peaks of negative ellipticity at 208 nm and 222 nm indicating that Hb is a predominantly in helical secondary structure. The CD spectrum (the data not shown) of met Hb remained almost unchanged upon addition of H2O2. The results suggest that the high H2O2 used in our experiments did not induce appreciable secondary structure changes in the proteins.

3.4. Multicomponent analysis of hemoglobin species

To maximize optical accuracy, a three-component system to quantify Hb species (oxy/ferrous, met/ferric, and deoxy) were chosen and optical density measurements were carried out at the 560 nm, 576 nm, and 630 nm wavelengths as previously reported by Benesch [17] and Winterbourn [21]. At these wavelengths, the absorbance of one component is at a maximum, whereas the contribution of other species is negligible. The concentrations (µM, heme based) for ferrous, deoxy, and ferric HbA are derived from the extinction coefficients listed in Table 1 and are represented by the following equations:

When oxidized Hb is used, the following wavelengths, 541 nm, 576 nm, and 630 nm were chosen to calculate Hb concentrations using extinction coefficients listed in Table 1 and are represented by the following equations:

Our extinction coefficients values summarized in Table 1 are generally in agreement with other reported values in literatures. However, in the case of ferrous Hb, the values are closer to those reported by Benches [17] and slightly higher than those reported by Winterbourn [21]. The values reported in this work for the ferryl species are contrasted with those reported recently by Herold et al. [35], and are somewhat higher particularly at 418 nm (Table 2). We believe these values represent accurate estimation of the extinction coefficients of ferryl Hb as we have paid careful attention to the transient nature of this species and we have also verified this species by other methodologies (e.g., by stopped flow and by derivtization with Na2S (data not shown)).

Table 2.

Comparison of hemoglobin concentration determinations among different methods.

| Samples n=3 |

Winterbourn Eq (µM)[21] | Benesch Eq (µM)[17] | This study (µM) | HPLC (µM)* |

Drabkin (µM) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxy | Met | Hemi | Total | Oxy | Met | Deoxy | Total | Oxy | Met | Deoxy | Total | |||

| HbA-st1 279.5 |

147.5 (±3.2) |

164.7 (±3.7) |

2.7 (±0.1) |

314.9 (±5.4) |

130.4 (±2.8) |

163.6 (±3.4) |

8.2 (±0.2) |

302.2 (±6.8) |

127.9 (±2.5) |

159.8 (±3.1) |

4.0 (±0.1) |

291.7 (±4.2) |

279.5 (±2.3) |

280.0 (±2.3) |

| HbA-st2 317.4 |

167.0 (±3.5) |

190.3 (±3.8) |

2.4 (±0.1) |

359.7 (±6.2) |

147.5 (±3.1) |

189.0 (±3.7) |

9.0 (±0.2) |

345.5 (±7.4) |

144.6 (±3.1) |

185.1 (±3.5) |

4.1 (±0.1) |

333.8 (±4.9) |

319.3 (±3.1) |

317.2 (±3.7) |

| HbA | 202.3 (±3.7) |

−2.4 (±0.1) |

−8.5 (±0.1) |

191.4 (±4.3) |

175.9 (±2.8) |

−3.4 (±0.1) |

5.7 (±0.1) |

178.2 (±3.9) |

177.7 (±1.9) |

−0.8 (±0.1) |

−0.2 (±0.0) |

176.7 (±2.7) |

177.8 (±2.1) |

175.6 (±2.3) |

| MetHb | 1.8 (±0.1) |

186.9 (±3.2) |

0.3 (±0) |

189.1 (±3.3) |

3.7 (±0.1) |

185.9 (±3.4) |

−1.1 (±0.1) |

188.5 (±4.2) |

−0.4 (±0.1) |

179.5 (±2.1) |

−0.8 (±0.1) |

178.3 (±2.9) |

176.6 (±1.8) |

174.2 (±2.7) |

3.5. Reversed phase HPLC method for the estimation of hemoglobin and heme concentrations

Oxidation of Hb with low levels of H2O2 or when Hb undergoes its own H2O2 production during autooxidation has been shown to induce α/β subunit oxidative and post translational modifications as well as the formation of altered heme products (as a result of heme crosslinking to the protein). These oxidation induced alterations have been well characterized by RP-HPLC and mass spectrometric methods [29, 36, 37].

We developed and tested a novel RP-HPLC to estimate Hb/heme levels and to confirm oxidative and redox changes within the protein in conjunction with our photometric methods. Aliquots (20 µg) of ferrous HbA and Met Hb solutions were injected into a C3 column (4.6×250 mm). The RP-HPLC separation was monitored at 280 nm (for heme and globin chains) and 405 nm (heme), and the results of the HPLC analyses are shown in the Fig. 5. Fig. 5A and 5B show typical elution profiles of ferrous and ferric Hb respectively. In Both cases, heme, most hydrophilic group was eluted at 18 min [38]. This elution was followed by the β globin chain at 26 min which is relatively more hydrophobic than α globin chains which was eluted at 28 min. The baseline absorption in the case of the ferrous sample is uneven with some scatter. This may be due to the fact that ferric Hb releases heme groups faster than ferrous Hb [39], resulting in a better resolution of both the heme and protein peaks in the ferric sample. Moreover, the peak height of ferrous HbA (Fig. 5C) is significantly lower than those of ferric Hb (Fig. 5D). This may be explained by a weaker optical absorption of the ferrous as opposed to the ferric heme at 405 nm (108.3 mM−1cm−1 at 405 nm for ferrous Hb vs 167.0 mM−1cm−1 at 405 nm for metHb, Table 2). It is important therefore to couple spectrophotometric as well chromatographic techniques to routinely and accurately estimate oxidative changes that accompanying Hb redox transitions and that these changes should be factored in Hb extinction and concentration measurements [3, 29].

In order to test the utility of our HPLC method in estimating the levels of both free Hb and heme in plasma, a standard curve was first constructed for the determination of Hb and heme concentrations in biological samples. A wide range of HbA solutions (5µM to 65 µM) were incubated in 400 µM of potassium iron cyanate solution at room temperature for 15 mins to fully obtain oxidized form of Hb, and then aliquot (25 µL) of the standard solutions were injected into C3 RP-HPLC column (Fig. 6). Hb elutes were monitored at 405 nm (Fig. 6A), and a plot of the integrated heme peak area (18 min) against the HbA (heme) concentrations was constructed (inset for Fig. 6A). Although there are some differences in the peak heights in our control samples (heme/protein), measurement of area under the curve (AUC) on the other hand yielded uniformed values for all peaks in our HPLC profiles (Figure 5 and 6).

An aliquot (50 µL) of plasma from normal human and SCD patients were mixed with 100 µL of 400 µM of potassium iron cyanate solution, were also analyzed by the same HPLC method, and the HPLC profiles were monitored at 405 nm are shown in Fig. 6A. HPLC profiles for these samples that were monitored at 280 nm are shown in Fig. 6B along with the HPLC curve of HbA control (black curve). As can be seen in Fig. 6B, there were several complex peaks found in the plasma eluted between 19min to 25 min. However, closer inspection of these profiles (inset for Fig. 6B) reveals small but sharp peaks eluted out at 17.5 min which represent the heme group. By integrating the area under the curve (AUC) of heme peaks and using the standard curve (Fig. 6A), we were able to calculate the free Hb concentration in the plasma, which was 45.6 mg/100mL for the SCD patient and 10.5 mg/100mL for the normal human blood. These values are higher than those reported by others early, which are 2–33 mg/100 mL for SCD plasma [40, 41] and lower than 5 mg/100mL for normal plasma [42]. We are currently comparing the estimation of heme levels using our HPLC method with those commercially available photometric methods used widely in the literature.

3.6. Comparison of various methods for the determination of hemoglobin redox forms

Finally, using our photometric and chromatographic methods we compared our extinction coefficient values with those calculated based on extinction coefficients reported by others. For this purpose we included four Hb solutions designated as standard solutions HbA-st1, HbA-st2, and two tests (unknown) solutions, HbA and met HbA (Table 2). Table 2 compares the calculated values for the different Hb redox species (heme) with those previously reported values by Winterbourn [21], and Bensches [17] using our in-house derived standards and two test solutions of HbA and, metHb respectively. We have also listed the values for total Hb concentrations calculated for these solutions using our HPLC and the standard Drabkin methods (Table 2). It is interesting to note that total Hb concentrations calculated by photometric method in our study matched well with those values derived using the HPLC and the Drabkin methods. There were however, some variations in the values of oxy, met and hemichrome levels derived from the Winterbourn and Benesch equations and our methods. This may be due to variations in the quality of preparation of different Hb redox forms among the three groups. For calculating total concentration of Hb, Drabkin’s method was using an extinction coefficient of 11.0 mM−1cm−1. As shown in Table 2, all spectrophotometric methods give slightly higher values than the Drabkin’s methods. However, our photometric as well HPLC values were the closest to those generated by the Drabkin method.

In summary, we have presented in this report, a new set of extinction coefficients using highly purified redox forms of human Hb. To capture the ferryl heme, a transient redox form of Hb, we have specifically derived a new set of extinction coefficients. An HPLC method was also developed that can be used in conjunction with these photometric methods to enable a more precise estimation of Hb subunit integrity particularly after oxidation with H2O2. The application of these methods and their robustness were tested in human blood samples from normal and sickle cell subjects. These redox-specific extinction coefficients and method calculations will better compliment studies evaluating the role of Hb redox toxicity and disease pathogenesis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH/NHLBI) grant P01-HL110900 (AIA), and grants from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (MODSCI) (AIA).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Camus SM, De Moraes JA, Bonnin P, Abbyad P, Le Jeune S, Lionnet F, Loufrani L, Grimaud L, Lambry JC, Charue D, Kiger L, Renard J-M, Larroque C, Le Clésiau H, Tedgui A, Bruneval P, Barja-Fidalgo C, Alexandrou A, Tharaux P-L, Boulanger CM, Blanc-Brude OP. Circulating cell membrane microparticles transfer heme to endothelial cells and trigger vasoocclusions in sickle cell disease. Blood. 2015;125:3805–3814. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-07-589283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chintagari NR, Nguyen J, Belcher JD, Vercellotti GM, Alayash AI. Haptoglobin attenuates hemoglobin-induced heme oxygenase-1 in renal proximal tubule cells and kidneys of a mouse model of sickle cell disease. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2015;54:302–306. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kassa T, Jana S, Strader MB, Meng F, Jia Y, Wilson MT, Alayash AI. Sickle Cell Hemoglobin in the Ferryl State Promotes betaCys-93 Oxidation and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Epithelial Lung Cells (E10) J Biol Chem. 2015;290:27939–27958. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.651257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belcher JD, Chen C, Nguyen J, Milbauer L, Abdulla F, Alayash AI, Smith A, Nath KA, Hebbel RP, Vercellotti GM. Heme triggers TLR4 signaling leading to endothelial cell activation and vaso-occlusion in murine sickle cell disease. Blood. 2014;123:377–390. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-04-495887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mollan TL, Alayash AI. Redox reactions of hemoglobin: mechanisms of toxicity and control. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;18:2251–2253. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reeder BJ. The Redox Activity of Hemoglobins: From Physiologic Functions to Pathologic Mechanisms. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 2010;13:1087–1123. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonaventura C, Henkens R, Alayash AI, Banerjee S, Crumbliss AL. Molecular Controls of the Oxygenation and Redox Reactions of Hemoglobin. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 2013;18:2298–2313. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rifkind JM, Ramasamy S, Manoharan PT, Nagababu E, Mohanty JG. Redox Reactions of Hemoglobin. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 2004;6:657–666. doi: 10.1089/152308604773934422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deuel JW, Vallelian F, Schaer CA, Puglia M, Buehler PW, Schaer DJ. Different target specificities of haptoglobin and hemopexin define a sequential protection system against vascular hemoglobin toxicity. Free Radic Biol Med. 2015;89:931–943. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooper CE, Schaer DJ, Buehler PW, Wilson MT, Reeder BJ, Silkstone G, Svistunenko DA, Bulow L, Alayash AI. Haptoglobin Binding Stabilizes Hemoglobin Ferryl Iron and the Globin Radical on Tyrosine β145. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 2013;18:2264–2273. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chintagari NR, Jana S, Alayash AI. Oxidized Ferric and Ferryl Forms of Hemoglobin Trigger Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Injury in Alveolar Type I Cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2016;55:288–298. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2015-0197OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vandegriff KD, Malavalli A, Wooldridge J, Lohman J, Winslow RM. MP4, a new nonvasoactive PEG-Hb conjugate. Transfusion. 2003;43:509–516. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2003.00341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elmer J, Harris DR, Sun G, Palmer AF. Purification of Hemoglobin by Tangential Flow Filtration with Diafiltration. Biotechnology progress. 2009;25:1402–1410. doi: 10.1002/btpr.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou Y, Jia Y, Buehler PW, Chen G, Cabrales P, Palmer AF. Synthesis, biophysical properties, and oxygenation potential of variable molecular weight glutaraldehyde-polymerized bovine hemoglobins with low and high oxygen affinity. Biotechnology Progress. 2011;27:1172–1184. doi: 10.1002/btpr.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang W, Yan K, Dai P, Tian J, Zhu H, Chen C. A Novel Hemoglobin-Based Oxygen Carrier, Polymerized Porcine Hemoglobin, Inhibits H2O2-Induced Cytotoxicity of Endothelial Cells. Artificial Organs. 2012;36:151–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.2011.01305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Acharya SA, Acharya VN, Kanika ND, Tsai AG, Intaglietta M, Manjula BN. Non-hypertensive tetraPEGylated canine haemoglobin: correlation between PEGylation, O(2) affinity and tissue oxygenation. The Biochemical Journal. 2007;405:503–511. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benesch RE, Benesch R, Yung S. Equations for the spectrophotometric analysis of hemoglobin mixtures. Anal Biochem. 1973;55:245–248. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(73)90309-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drabkin DL, Austin JH. Spectrophotometric studies: II. Preparations from washed blood cells; Nitric oxide hemoglobin and sulfhemoglobin. J. Biol. Chem. 1935;112:51–65. [Google Scholar]

- 19.International Committee for Standardization in Haematology. British Journal of Haematology. 1967;13:71–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1967.tb00749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zijlstra WG. Standardisation of Haemoglobinometry: History and New Challeges. Haematology International. 1997;1:125–132. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Winterbourn CC. Oxidative reactions of hemoglobin. Methods Enzymol. 1990;1990:265–272. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)86118-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whitburn KD, Shieh JJ, Sellers RM, Hoffman MZ, Taub IA. Redox transformations in ferrimyoglobin induced by radiation-generated free radicals in aqueous solution. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:1860–1869. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manjula BN, Acharya AS. Purification and molecular analysis of hemoglobin by high-performance liquid chromatography. Totowa: Humana Press; 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aebi H. Catalase in vitro. Methods Enzymol. 1984;105:121–126. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(84)05016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Di Iorio EE. Preparation of derivatives of ferrous and ferric hemoglobin. Methods Enzymol. 1981;76:57–62. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(81)76114-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Antonini E, Brunori M. Chapter 2. The derivatives of ferrous hemoglobin and myoglobin. In: Antonini E, Brunori M, editors. Hemoglobin and myoglobin in their reactions with ligands. Amsterdam: North-Holland Pub. Co; 1971. pp. 13–39. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jia Y, Alayash AI. Stopped-flow fluorescence method for the detection of heme degradation products in solutions of chemically modified hemoglobins and peroxide. Analytical Biochemistry. 2002;308:186–188. doi: 10.1016/s0003-2697(02)00233-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alayash AI, Summers AG, Wood F, Jia Y. Effects of Glutaraldehyde Polymerization on Oxygen Transport and Redox Properties of Bovine Hemoglobin. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2001;391:225–234. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2001.2426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strader MB, Kassa T, Meng F, Wood FB, Hirsch RE, Friedman JM, Alayash AI. Oxidative instability of hemoglobin E (β26 Glu→Lys) is increased in the presence of free α subunits and reversed by α-hemoglobin stabilizing protein (AHSP): Relevance to HbE/β-thalassemia. Redox Biology. 2016;8:363–374. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meng F, Manjula BN, Tsai AG, Cabrales P, Intaglietta M, Smith PK, Prabhakaran M, Acharya SA. Hexa-thiocarbamoyl Phenyl PEG5K Hb: Vasoactivity and Structure. The Protein Journal. 2009;28:199–212. doi: 10.1007/s10930-009-9185-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dijkhuizen P, Buursma A, Gerding AM, AZijlstra WG. Sulfhaemoglobin. Absorption spectrum, millimolar extinction coefficient at lambda = 620 nm, and interference with the determination of haemoglobin and of haemiglobincy anide. Clin. Chim. Acta. 1977;78:479–487. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(77)90081-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mollan TL, Banerjee S, Wu G, Parker Siburt CJ, Tsai A-L, Olson JS, Weiss MJ, Crumbliss AL, Alayash AI. α-Hemoglobin Stabilizing Protein (AHSP) Markedly Decreases the Redox Potential and Reactivity of α-Subunits of Human HbA with Hydrogen Peroxide. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2013;288:4288–4298. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.412064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patel RP, Svistunenko DA, Darley-Usmar VM, Symons MC, Wilson MT. Redox cycling of human methaemoglobin by H2O2 yields persistent ferryl iron and protein based radicals. Free Radic Res. 1996;25:117–123. doi: 10.3109/10715769609149916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cashon RE, Alayash AI. Reaction of Human Hemoglobin HbA0 and Two Cross-Linked Derivatives with Hydrogen Peroxide: Differential Behavior of the Ferryl Intermediate. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 1995;316:461–469. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1995.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herold S, Rehmann F-JK. Kinetics of the reactions of nitrogen monoxide and nitrite with ferryl hemoglobin. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2003;34:531–545. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)01355-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jia Y, Buehler PW, Boykins RA, Venable RM, Alayash AI. Structural basis of peroxide-mediated changes in human hemoglobin: a novel oxidative pathway. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:4894–4907. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609955200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Strader MB, Hicks WA, Kassa T, Singleton E, Soman J, Olson JS, Weiss MJ, Mollan TL, Wilson MT, Alayash AI. Post-translational Transformation of Methionine to Aspartate Is Catalyzed by Heme Iron and Driven by Peroxide: A NOVEL SUBUNIT-SPECIFIC MECHANISM IN HEMOGLOBIN. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2014;289:22342–22357. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.568980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Masala B, Manca L. Detection of globin chains by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography. Methods Enzymol. 1994;231:21–44. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(94)31005-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kassa T, Jana S, Meng F, Alayash AI. Differential heme release from various hemoglobin redox states and the upregulation of cellular heme oxygenase-1. FEBS Open Bio. 2016;6 doi: 10.1002/2211-5463.12103. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Naumann HN, Diggs LW, Barreras L, Williams BJ. Plasma Hemoglobin and Hemoglobin Fractions in Sickle Cell Crisis. American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 1971;56:137–145. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/56.2.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reiter CD, Wang X, Tanus-Santos JE, Hogg N, Cannon RO, Schechter AN, Gladwin MT. Cell-free hemoglobin limits nitric oxide bioavailability in sickle-cell disease. Nat Med. 2002;8:1383–1389. doi: 10.1038/nm1202-799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.MedlinePlus, serum free hemoglobin test. http://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/003677.htm.

- 43.van Assendelft OW, Zijlstra WG. Extinction coefficients for use in equations for the pectrophotometric analysis of haemoglobin mixtures. Anal Biochem. 1975;69:43–48. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(75)90563-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Assendelft OW, Buursma A, AZijlstra WG. Stability of haemiglobincyanide standards. J. Clin. Pathol. 1996;49:275–277. doi: 10.1136/jcp.49.4.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zwart A, van Assendelft OW, Bull BS, England JM, Lewis SM, Zijlstra WG. Recommendations for reference method for haemoglobinometry in human blood (ICSH standard 1995) and specifications for international haemiglobinocyanide standard (4th edition) Journal of Clinical Pathology. 1996;49:271–274. doi: 10.1136/jcp.49.4.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Waterman MR. Spectral characterization of human hemoglobin and its derivatives. Methods Enzymol. 1978;52:456–463. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(78)52050-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van Kampen EJ, Zijlstra WG. Spectrophotometry of Hemoglobin and Hemoglobin derivatives. Advances in Clinical Chemistry. 1983;23:199–257. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2423(08)60401-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vandegriff KD, Malavalli A, Minn C, Jiang E, Lohman J, Young MA, Samaja M, Winslow RM. Oxidation and haem loss kinetics of poly(ethylene glycol)-conjugated haemoglobin (MP4): dissociation between in vitro and in vivo oxidation rates. Biochemical Journal. 2006;399:463–471. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]