Abstract

This study reports dose-response estimates for the relative risk (RR) and population attributable risk (PAR) between acute alcohol use and serious suicide attempt. Data were analyzed on 272 suicide attempters arriving at 38 emergency departments (EDs) within six hours of the event in 17 countries. Case-crossover analysis, pair-matching the number of standard drinks consumed within the six hours prior to the suicide attempt with that consumed during the same six-hour period the previous week, was performed using fractional polynomial analysis for dose-response. Every drink increased the risk of a suicide attempt by 30%, even one-two drinks was associated with a sizable increase in the risk of a serious suicide attempt and a dose-response was found for the relationship between drinking 6 hours prior and the risk of a suicide attempt up to 20 drinks. Acute use of alcohol was responsible for 35% PAR of all suicide attempts. While very high levels of drinking were associated with larger RRs of suicide attempt, the control and reduction of smaller quantities of acute alcohol use also had an impact on population levels of suicide attempt, as showed here for the first time with our PARs estimates. Interventions to stop drinking or at least decrease levels of consumption could reduce the risk of suicide attempt. Screening people more at risk to suffer these acute effects of ethanol and offering interventions that work to these high risk groups is a matter of urgent new research in the area.

Keywords: Alcohol, case-crossover, emergency department, risk, suicide attempt

Introduction

New estimates from the Global Burden of Disease Study (GBD-2010) places alcohol as the fifth leading risk factor for disability-adjusted life year (DALYS) on a global scale, with 3.9% of all DALYS and was the leading risk factor among 14–49 year old individuals. Interpersonal violence and suicide (self-injury) alone contributed with about an eighth (0.5%) of this burden (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation & GBD 2013 2013). On the other hand, self-injury was responsible for 1.5% of global DALYS, 4.8% of all female deaths and 5.7% of all males deaths in 2010 and ranked in the 13th place for all deaths (Lozano et al. 2013) and since globally about 1 in every 5 suicide deaths/DALYs is attributable to alcohol (World Health Organization 2014) there is a considerable interest on how public policies to reduce alcohol could decrease suicide worldwide (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of the Surgeon General and National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention 2012; Wilcox, Conner & Caine 2004). Preventive efforts to reduce suicide have paid close attention to suicide attempt (Mann et al. 2005) which is one of the main risk factors for suicide (Neeleman, de Graaf & Vollebergh 2004) and itself a cause of great psychological suffering.

The relation between alcohol use and the risk of suicide attempt has proven to be complex. Part of this complexity lay in that alcohol may have a chronic and an acute impact on suicide attempt (Hufford 2001). While the chronic impact of alcohol use on suicide attempt, expressed by measures of population consumption (per capita alcohol use) individual measures of number of standard drinks on a given year or the presence of alcohol use disorder, has been studied for a long time (Borges & Loera 2010; Conner, McCloskey & Duberstein 2008) there is a great scarcity of studies on the impact of acute alcohol use on suicide attempt (Conner 2015). Even when several reports are available on the seemly high prevalence of acute alcohol use on suicide or suicide attempts (Cherpitel, Borges & Wilcox 2004), to our knowledge only 6 studies (Bagge et al. 2013; Borges et al. 2004a; Borges et al. 2006; Borges & Rosovsky 1996; Branas et al. 2011; Powell et al. 2001) have provided relative risk (RR) estimates for this relationship. Only 3 have provided dose-response estimates (Bagge et al. 2013; Borges & Rosovsky 1996; Branas et al. 2011). These dose-response estimates are nevertheless limited in that they only show estimates for a “low” drinking group and a “high” drinking group.

Full estimates of dose-response relationships in this area are nevertheless important as an argument for causality and as argument for the public health impact that a given measure of alcohol control may have on the burden of injury (National health and medical research council 2009) and in particular on suicide. Prior meta-analyses on dose-response relationship between acute alcohol use and injury (Taylor et al. 2010) found that “the risk of injury rises monotonically with increasing alcohol consumption…”, but not only the risk for intentional injury was higher than the ones observed for motor vehicle or falls but that also the relationship of acute alcohol use and intentional injury was non-linear (that is, intentional injuries having a greater proportional per-drink increase in risk). A new report (Cherpitel et al. 2015a) found a monotonic increase in RR of injury by increasing alcohol prior to the injury (starting from one drink and up to 30 drinks) and a steeper RR function curve for violence related injury, compared to traffic and falls. These RR functions were also associated with different levels of alcohol-attributable fraction (AAF) of injury (Cherpitel et al. 2015b) or the proportion of injury which would be eliminated in the absence of the risk factor, also known as population attributable risk (PAR) (Rothman, Greenland & Lash 2008).

Clearly, a dose-response estimate of the relationship between acute alcohol drinking and the risk of suicide attempt and corresponding PARs, while necessary, are lacking. Building from a large sample of patients attending emergency departments around the globe (Cherpitel et al. 2015a; Cherpitel et al. 2015b) that reported on their acute alcohol use prior to an injury and a comparable period in the prior week, the goal of this report is to delve into the dose-response relationship between acute alcohol use and serious suicide attempt. Moreover, we also provide population attributable risk estimates for this sample that could be used for monitoring the public health impact of alcohol control measures on suicide.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample

The methods for this case-crossover study are similar to those used previously in emergency department (ED) studies from the World Health Organization (WHO) Collaborative Study on Alcohol and Injury (Borges et al. 2006) and the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) study in EDs (Borges et al. 2013) that reported on the risk of alcohol use and injury. Following the WHO-PAHO standard protocol, probability samples were drawn from patients aged 18 years or older admitted within 6 hours of an injury at each site; each shift during each day of the week was represented equally in the sampling. Patients were approached as soon as possible to obtain informed consent for participation in the study. Interviewers were trained and supervised by study collaborators. Interviewers administered a standard 25-minute questionnaire. Further details on the general methodology, questionnaire development and training for the WHO study and the associated PAHO study can be found elsewhere (Borges et al. 2013; Cherpitel et al. 2005).

For this study, only patients attending the ED who reported their cause of injury as a consequence of an intentional self-inflicted (suicide attempt) were included here. The following study sites contributed with cases: Argentina (2001), Belarus (2001), Brazil (2001), Canada (2002 and 2009), China (2001), Costa Rica (2012–2013), Dominican Republic (2010), Guatemala (2011), Guyana (2011), India (2001), Ireland (2003–2004), Korea (2007), Mexico (2002), Nicaragua (2010), Panama (2010), Sweden (2001) and Taiwan (2009–2010). Ethical approval was obtained from institutional review boards in each participating country, as well as by the WHO and PAHO Ethics Review Committee.

The interview included questions on whether the participant reported drinking during the 6 hours before the suicide attempt and the same 6-hour period in the previous week. For alcohol use, during the 6 hours prior to the suicide attempt, patients were asked: ‘In the 6 hours before and up to you attempt suicide, did you have any alcohol to drink, even one drink?’ (yes/no). Information on alcohol use at the same time in the previous week was elicited as follows: ‘In this next section, I am going to ask you about what you were doing exactly 1 week ago. Think about the time you had your suicide attempt (today) and remember the same time a week ago. Last week at the same time, did you have any alcohol to drink in the 6 hours leading up to this time?’ (yes/no). If patients reported drinking prior to the suicide attempt or in the prior week, they were asked the beverage-specific number and size of containers consumed in the six-hour period prior to the suicide attempt. The volume of alcohol consumed during the 6-hour period was analyzed by converting the number and size of drinks of wine, beer, spirits and local beverages to pure ethanol, and summing across beverage types, using a standard drink size of 16 ml (12.8 grams) as a common volume measure across beverages.

Data analysis

Patients who reported drinking at any time within the 6 hours prior to injury were considered exposed cases. The pair-matching approach compared the reported use of alcohol of each patient during the 6 hours prior to the suicide attempt with their respective use of alcohol during the same time-period on the same day in the previous week. Conditional logistic regression was used to calculate matched-pair RRs and 95% confidence intervals (CI) [19]. Three models were calculated: one with alcohol prior as a dichotomous exposure, and two with alcohol volume as continuous: linear and polynomial. The analysis of dose-response relationship between the amount of drinking 6 hours prior and the suicide attempt used the second-degree fractional polynomial and calculations of AAFs are explained in full details on two prior works from our group (Cherpitel et al. 2015a; Cherpitel et al. 2015b). Briefly, this approach circumvents the more usual categorized alcohol exposure levels that while assumes no specific form or shape of the dose response implies that the RR of suicide attempt changes abruptly at the somehow arbitrarily set cut-points. As an alternative to categorical step-functions, fractional polynomials have recently been used to estimate the alcohol and injury dose-response relationship in a systematic review and meta-analysis (Taylor et al. 2010). Models were fitted using the STATA version 13.1 (Stata Corp LP 2013) fracpoly command. Royston (Royston, Ambler & Sauerbrei 1999) provides details of model fitting as well as estimation of analytic 95% CIs. PAR where calculated based on the RR estimates, evaluating the fractional polynomial function at the observed mean volume for a given range of drinks, by the prevalence of drinking six hours prior in that range: PARi = Prevalencei × (1−1/RRi) (Steenland & Armstrong 2006). The total PAR was computed as the summation of all PARi.

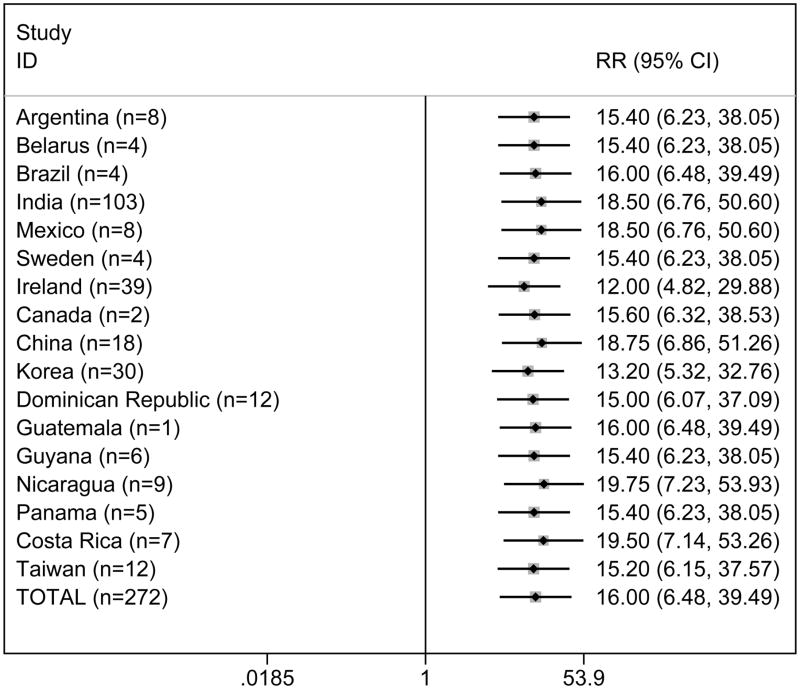

RESULTS

The merged sample of patients that attempted suicide summed 272. Most were males (66.2%) with a median age of 28 years (Table 1). Among these 272 cases, 37% reported any alcohol use 6 hours prior to the attempt. The common, merged, RR of suicide attempt given any alcohol consumption 6 hours prior by the matched analysis was RR=16.00; 95% CI=(6.48–39.49). Figure 1 shows the number of suicide attempt cases that each study site contributed with and the variation in estimates when these sites were deleted from the common estimate. The common RR varied from a low RR estimate of 12.0 (4.8–29.9) when we deleted the site of Ireland to a high RR of 19.8 (7.2–53.9) when we deleted the site of Nicaragua. These variations are all within the confidence intervals of the common estimate. Alcohol 6 hours prior, as a continuous variable modeled on a liner regression, was associated with an increase RR=1.30; 95% CI = (1.18–1.44). That is, an increase in one drink was associated with a 30% increase in the likelihood of a suicide attempt.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic and alcohol use among suicide attempt cases in the ED sample (n=272).*

| n | % or median (IQR) | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| Sex | ||

| Female | 92 | 33.82 |

| Male | 180 | 66.18 |

| Age (years) | 267 | 28 (13) |

| Education (years) | 269 | 10 (6) |

| Working at least 30 hours | ||

| Yes | 138 | 52.87 |

| No | 123 | 47.13 |

| Alcohol 6 hours prior | ||

| Yes | 101 | 37.13 |

| No | 171 | 62.87 |

Valid sample: those who reported complete information both on alcohol volume before injury and same time the previous week.

IQR - Interquartile range; ED- Emergency Department

Data from 38 Emergency Departments (ED) in 17 countries (only 35 ED contributed with self-injury cases)

The following study sites contributed with cases: Argentina, Belarus, Brazil, Canada, China, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Guatemala, Guyana, India, Ireland, Korea, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Sweden and Taiwan.

Figure 1.

Relative Risk of self-injury by any alcohol use six hours prior. Matched analysis. Total and without one study at a time.

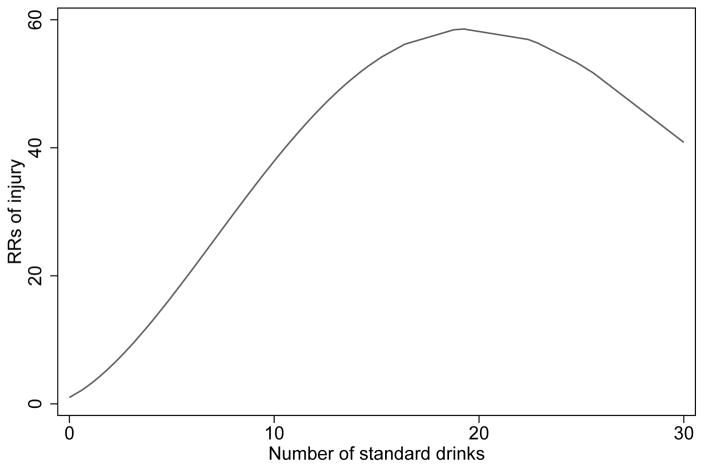

Table 2 presents the dose-response estimates for alcohol use and suicide attempt up to 30 drinks. The number of drinkers at each consumption level ranged from 9 to 28 and the prevalence at each consumption level ranged from 3.28% up to 10.08%. First, even one-two drinks increased the likelihood of a suicide attempt, with an RR=3.98; 95% CI=(2.34–6.77) and the RRs for up to 30 drinks was 54.33 (7.43–397.46). In all instances the confidence intervals were wide, reflecting the fact that even with such large sample size, there are few discordant pairs for specific levels of drinking. The corresponding Graph of these RRs (Figure 2) suggests a monotonic increase in risk of suicide attempt with more alcohol consumption up to 20 drinks and then a decrease in risk that nevertheless keeps being extremely high. Table 2 also presents the corresponding PAR associated with these drinking levels. It is interesting that while the lower categories of drinking have comparatively lower RRs, these categories have a large number of cases, similar or sometimes higher prevalences of exposure and PARs that are lower but still comparable with those of higher number of drinks (with the exception of category (10,15). Across levels of drinking, the summation of PARs implies that the elimination of alcohol would reduce suicide attempts by about 35% (28.58–40.94). It should be noted here that suicide attempt cases appear to be overrepresented by India, with 38% of the total cases coming from that country. Sensitivity analysis, removing India, made little difference in the common risk estimate, although PAR increased from 35% to 51%, possibly reflecting typically lighter drinking patterns in that country (data not shown).

Table 2.

Alcohol Relative Risk and Attributable Fraction estimates by levels of alcohol consumed six hours before suicide attempt in the ED sample (n=272)

| Alcohol intake before injury1,6

|

Relative Risk3

|

Attributable Fraction4

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | n | Prevalence2 | RR | 95% CI | AF | 95% CI |

|

|

|

|

||||

| No drinking | 171 | - | 1 | - | - | - |

| ≤2 | 9 | 3.28 | 3.98 | (2.34–6.77) | 2.45 | (0.37–4.54) |

| 2.1–4 | 10 | 3.64 | 9.53 | (4.05–22.43) | 3.26 | (1.11–5.42) |

| 4.1–6 | 12 | 4.31 | 18.61 | (6.26–55.32) | 4.07 | (1.83–6.32) |

| 6.1–8 | 13 | 4.97 | 24.82 | (7.62–80.87) | 4.77 | (2.27–7.27) |

| 8.1–10 | 12 | 4.37 | 35.50 | (9.81–128.42) | 4.25 | (1.94–6.56) |

| 10.1–15 | 28 | 10.08 | 47.43 | (12.05–186.63) | 9.87 | (6.41–13.32) |

| 15.1–30 | 17 | 6.20 | 54.33 | (7.43–397.46) | 6.08 | (3.24–8.93) |

| Total5 | 272 | 36.85 | - | - | 34.76 | (28.58–40.94) |

Number of standard drinks

Prevalence rates do not match exactly with sample frequencies, since some studies were weighted.

Relative risks are fractional polynomial estimates based on the mean volume of each volume category (e.g. 1.37 drinks for the (0,2] range).

Specific Volume Alcohol Attributable Fraction (SVAAF) = Pi*(1−1/RRi) in which Pi is the prevalence of drinking at a given volume among total injured patients (cases) and RRi the relative risk of injury for a given volume compared to no drinking.

The total includes the sum of the prevalence and SVAAF across dose levels

10 measures (seven subjects) were capped to 30 drinks

Matched RR from lineal model with capped volume = 1.30; 95% CI = (1.18–1.44)

Figure 2.

Relative Risk of self-injury by alcohol volume consumed before injury. Best fit polynomial model with powers 0 (i.e. ln(x)), 2. Volume capped to 30 drinks (10 measures in 7 subjects).

Since the RR for a range of drinking prior to injury (as shown in table 2) was calculated based on both the functional form of the polynomial function and the mean value of drinking in a given range (second column of table 2) our RR estimates did not fully reflect the form of the exponential function shown in Figure 2, where there is an increase in risk up to 20 drinks and then decrease. This happens because the last range (15–30) has a mean value of 24.2 drinks, which is close to the inflexion point of the curve and the estimate is still higher than the previous one. A lower estimate could be shown if the mean value of the range was higher.

DISCUSSION

The main findings of this research is that every drink increased the risk of a suicide attempt by 30%, even one-two drinks were associated with a sizable increase in the risk of a serious suicide attempt and a dose-response was found for the relationship between drinking 6 hours prior and the risk of a suicide attempt up to 20 drinks, with lower but still high risks after 20 drinks. While very high levels of drinking were associated with large RRs of suicide attempt, the control and reduction of smaller quantities of acute alcohol use could have a similar impact on population levels of suicide attempt, as showed here for the first time with our PARs estimates. The PARs findings reported here may be underestimated, given the overrepresentation of India with lighter drinking patterns.

These findings are in line with prior research in this area, showing a relationship between acute alcohol use and suicide attempt (Bagge et al. 2013; Borges et al. 2004a; Borges et al. 2006; Borges & Rosovsky 1996; Branas et al. 2011; Powell et al. 2001). Most importantly, the case-crossover methodology assured that fixed personal characteristics, such as age and sex, are kept constant and does not confound this association. Even more, this methodology also implies that our estimate on the role of acute alcohol use is independent of patient’s chronic alcohol use (alcohol use disorder) a matter of great relevance in the field. While in line with prior work, the findings reported here also brings novel information. First, the 30% increase on risk per-drink (16 ml or 12.8 grs of ethanol) is higher than increases reported for falls, motor vehicle and other unintentional injuries but not for intentional injury as reported before (Taylor et al. 2010). A comparison with prior results from our group (Cherpitel et al. 2015a) shows nevertheless that our dose-response estimates are higher for suicide attempt than for any other cause of injury, including violence-related injury, for each level of consumption. Secondly, we show here for the first time that even one-two drinks were associated with an increase in suicide attempt, a matter not reported before by prior dose-response estimates (Bagge et al. 2013; Borges & Rosovsky 1996; Branas et al. 2011) probably because of sample size limitations. As per our results, 35% of all attempts were attributable to acute alcohol, an estimate that is higher than the current value of about 20% of all DALYS ((World Health Organization 2014), figure 14). Current estimates of PAR for alcohol and suicide are based mainly on death by suicide and chronic alcohol use and alcohol use dependence, while our estimate was based on acute use of alcohol. Combining these two estimates and RRs provided here, area a matter of future research. While our PAR estimate of 35% is high, it is nevertheless below the PAR of about 40% for acute alcohol use and violence-related injuries (Cherpitel et al. 2015b).

Since most of the drinking takes place at low levels of consumption, with smaller but non-negligible PARs, and by prior work in this area (Bagge et al. 2013; Borges et al. 2004a) most of the risk period occurs in the hour before the attempt, reducing drinking while important maybe a difficult task. An alternative is to act on other acute factors that, combined with drinking, put people on higher risk for a suicide attempt. Research delving into the coalescence between acute drinking and other acute events (such as anger, the presence of negative events or a depressive episode) that then may trigger an attempt is then an important task for new research (Bagge et al. 2014; Conner et al. 2014a; Conner et al. 2014b; Fang et al. 2012). This task will ask for new and challenging methodologies. The dose-response relationship reported here is novel in this area and shows a relationship between drinking and serious suicide attempt, with likely important consequences for patients under clinical care for mental disorders where acute drinking can have a devastating consequences (Sher et al. 2009).

Limitations

Similarly to prior reports from our group, this study is limited to analysis of data from patients with non-suicide attempts who attended specific EDs. Although the study design provides a representative sample of patients attending the ED from each facility, patients may not be representative of other facilities in the city or the country. Even if we merged 14,193 injured patients, we were only able to gather 272 cases of suicide attempt (less than 2% of the entire injury sample) and the dose-response estimates are thereby unstable. This is especially relevant for the higher consumption categories where we can observe large confidence intervals, for which an inflection on the risk curve was observed, suggesting that our study is limited when inspecting the shape of the curve for upper levels of alcohol use. Additionally, as is common with other studies conducted in EDs, cases cannot be assumed to be representative of other individuals who attempted suicide but did not seek medical attention. All analyses reported here are based on the patient’s reported alcohol consumption across different times, and it is possible that participants were more likely to recall their consumption more accurately immediately before an injury than during any previous period, thereby producing an overestimate of the association between alcohol and suicide attempt. Findings using control periods other than drinking during the previous week have been mixed suggesting either higher estimates (Borges et al. 2004b; Gerlich & Rehm 2010; Gmel & Daeppen 2007), lower estimates (Borges et al. 2013) or no differential report (Ye et al. 2013); this is a topic for further research. Despite the fact that case–crossover studies are well suited to control for between-person confounders, they do not remove the possibility that within-person confounders may exist; for example, that alcohol use followed an episode of other drug use. Because we lack measures of other variables that vary over time, such as cocaine use, and that could be considered as possible confounders of the relationship between acute alcohol use and injury, we are not able to adjust for these potential biases. Nevertheless, a prior study (Bagge et al. 2013) that included data on other time-varying variables does not support the idea that these estimates are much confounded by other drugs or negative life events. This is the largest case-crossover study reported to date but our sample size was still insufficient to preform analyses by gender or age groups.

CONCLUSION

Despite these limitations, this is one of the largest studies ever reported on acute alcohol use and non-fatal, serious suicide attempts with data coming from a large and representative sample of patients from several countries and regions of the world. Our results expand the common clinical and post-mortem finding that people who commit or attempt suicide have large traces of alcohol consumption, but we added to these prevalences the corresponding estimates of high and increasing levels of RR by drinking levels. Our results imply that acute alcohol use, independent of long term chronic use, poses a risk for a serious suicide attempt. Preventive efforts could target those at risk of episodes of intoxication and heavy drinking beyond merely screening for alcohol use disorders. Perhaps efforts directed to groups of persons with an already increased risk of a suicide attempt, such as patients consulting for suicide ideation and those with prior mental health disorders, would make interventions to reduce alcohol use more practical. Interventions to stop drinking or at least decrease levels of consumption could reduce the risk of a suicide attempt. Screening people more at risk to suffer these acute effects of ethanol and offering interventions that work to these high risk groups is a matter of urgent new research in the area.

Acknowledgments

The paper is based, in part on data collected by the following collaborators participating in the Emergency Room Collaborative Alcohol Analysis Project (ERCAAP) (C. J. Cherpitel, P.I., USA):W. Cook (USA), G. Gmel (Switzerland), A. Hope (Ireland); and collaborators participating in the WHO Collaborative Study on Alcohol and Injuries, sponsored by the World Health Organization and implemented by the WHO Collaborative Study Group on Alcohol and Injuries under the direction of V. Poznyak and M. Peden (WHO, Switzerland): V. Benegal (India); G. Borges (Mexico); S. Casswell (New Zealand); M. Cremonte (Argentina); R. Evsegneev (Belarus); N. Figlie and R. Larajeira (Brazil); N. Giesbrecht and S. Macdonald (Canada); W. Hao (China); S. Larsson and M. Stafstrom (Sweden); H. Sovinova (Czech Republic. A list of other staff contributing to the project can be found in the Main Report of the Collaborative Study on Alcohol and Injuries, WHO, Geneva. The paper is also based, in part, on data obtained by the following collaborators participating in the U.S. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (WHO/NIAAA Collaborative Study on Alcohol and Injury), under the direction of B. Grant and P. Chou (NIAAA, USA): W. Hao (China); S. Chun (Korea), and collaborators participating in the Pan American Health Organization Collaborative Study on Alcohol and Injuries, directed by M. Monteiro (PAHO, USA) and implemented C. J. Cherpitel (USA) and G. Borges (Mexico): V. Aparicio and A. de Bradshaw ( Panama); V. Lopez (Guatemala); M. Paltoo (Guyana); E. Perez (Dominican Republic); D. Weil (Nicaragua). We also acknowledge Julio Bejarano (Costa Rica) and Yi-Chyan Chen and Ming-Chyi Huang (Taiwan)-for providing their data. The authors alone are responsible for views expressed in this paper, which do not necessarily represent those of the other investigators participating in the ERCAAP, WHO, NIAAA or PAHO collaborative studies on alcohol and injuries, nor the views or policy of the World Health Organization, the U.S. National Institute on Alcohol and Alcoholism, or the Pan American Health Organization.

Supported by a grant from the U.S. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) (RO1 2 AA013750-04, Cheryl Cherpitel, PI)

Footnotes

This work was done while Guilherme Borges was on a consultancy for the Management of Substance Abuse (MSB), Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse (MSD)-World Health Organization (Geneva-Switzerland)-

A presentation of an initial version of this manuscript was done at the World Health Organization (WHO) SUBSTANCE USE AND SUICIDE IN THE INTERNATIONAL CONTEXT, GENEVA, SWITZERLAND, WHO HEADQUARTERS, 19–21 October 2015

Declarations of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author Contribution

Guilherme Borges: originated the study, collected data in Mexico, participated in planning and data analyses, and wrote the initial draft and the final version of the article.

Cheryl J. Cherpitel: originated the study, wrote drafts, and reviewed and approved the final version of the article.

Ricardo Orozco: participated in planning, analyzed the data, wrote drafts, and reviewed and approved the final version of the article.

Yu Ye: participated in planning, data cleaning, statistical modelling, and reviewed and approved the final version of the article.

Maristela Monteiro: participated in the PAHO planning for data collection and reviewed and approved the final version of the article.

Wei Hao: collected data in China, participated in planning and reviewed and approved the final version of the article.

Vikram Benegal: collected data in India, participated in planning and reviewed and approved the final version of the article.

References

- Bagge CL, Lee HJ, Schumacher J, Gratz K, Krull J, Holloman G. Alcohol as an acute risk factor for suicide attempt: A case-crossover analysis. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2013;74:552–558. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagge CL, Littefield AK, Conner KR, Schumacher J, Lee HJ. Near-term predictors of the intensity of suicidal ideation: An examination of the 24 hours prior to a recent suicide attempt. J Affect Disord. 2014;165:53–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges G, Cherpitel C, MacDonald S, Giesbrecht N, Stockwell T, Wilcox HC. A case-crossover study of acute alcohol use and suicide attempt. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2004a;65:708–714. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges G, Cherpitel C, Orozco R, Bond J, Ye Y, MacDonald S, Rehm J, Poznyak V. Multicentre study of acute alcohol use and non-fatal injuries: data from the WHO Collaborative Study on Alcohol and Injuries. Bull World Health Organ. 2006;84:453–460. doi: 10.2471/blt.05.027466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges G, Cherpitel C, Mondragón L, Poznyak V, Peden M, Gutierrez I. Episodic alcohol use and risk of nonfatal injury. Am J Epidemiol. 2004b;159:565–571. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges G, Loera CR. Alcohol and drug use in suicidal behaviour. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2010;23:195–204. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283386322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges G, Orozco R, Monteiro M, Cherpitel C, Then EP, López VA, Bassier-Paltoo M, Weil DA, Bradshaw AM. Risk of injury after alcohol consumption from case-crossover studies in five countries from the Americas. Addiction. 2013;108:97–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.04018.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges G, Rosovsky H. Suicide attempts and alcohol consumption in an emergency room sample. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 1996;57:543–548. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1996.57.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branas CC, Richmond TS, Ten Have TR, Wiebe DJ. Acute alcohol consumption, alcohol outlets, and gun suicide. Subst Use Misuse. 2011;46:1592–1603. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2011.604371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherpitel C, Borges G, Wilcox HC. Acute alcohol use and suicidal behavior: A review of the literature. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:18S–28S. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000127411.61634.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherpitel C, Ye Y, Bond J, Borges G, Monteiro M. Relative risk of injury from acute alcohol consumption: modeling the dose–response relationship in emergency department data from 18 countries. Addiction. 2015a;110:279–288. doi: 10.1111/add.12755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherpitel C, Ye Y, Bond J, Rehm J, Poznyak V, MacDonald S, Stafström M, Hao W Emergency Room Collaborative Alcohol Analysis Project (ERCAAP) and the WHO Collaborative Study on Alcohol and Injuries. Emergency Room Collaborative Alcohol Analysis Project (ERCAAP) and the WHO Collaborative Study on Alcohol and Injuries. Multi-level analysis of alcohol-related injury among emergency department patients: a cross-national study. Addiction. 2005;100:1840–1850. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherpitel CJ, Ye Y, Bond J, Borges G, Monteiro M, Chou P, Hao W. Alcohol Attributable Fraction for Injury Morbidity from the Dose-Response Relationship of Acute Alcohol Consumption: Emergency Department Data from 18 Countries. Addiction. 2015b;110:1724–1732. doi: 10.1111/add.13031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner KR. Commentary on “The modal suicide decedent did not consume alcohol just prior to the time of death: An analysis with implications for understanding suicidal behavior”. J Abnorm Psychol. 2015;124:457–459. doi: 10.1037/abn0000047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner KR, Bagge CL, Goldston DB, Ilgen MA. Alcohol and suicidal behavior: what is known and what can be done. Am J Prev Med. 2014a;47:S204–S208. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner KR, Gamble SA, Bagge CL, He H, Swogger MT, Watts A, Houston RJ. Substance-induced depression and independent depression in proximal risk for suicidal behavior. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2014b;75:567–572. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner KR, McCloskey MS, Duberstein PR. Psychiatric risk factors for suicide in the alcohol-dependent patient. Psychiat Ann. 2008;38:742–748. [Google Scholar]

- Fang F, Fall K, Mittleman MA, Sparén P, Ye W, Adami HO, Valdimarsdóttir U. Suicide and cardiovascular death after a cancer diagnosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1310–1318. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlich MG, Rehm J. Recall bias in case-crossover designs studying the potential influence of alcohol consumption. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2010;71:619. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gmel G, Daeppen JB. Recall bias for seven-day recall measurement of alcohol consumption among emergency department patients: implications for case-crossover designs. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2007;68:303–310. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hufford MR. Alcohol and suicidal behavior. Clin Psychol Rev. 2001;21:797–811. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(00)00070-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, GBD 2013. GBD Compare/Viz Hub. University of Washington; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, Abraham J, Adair T, Aggarwal R, Ahn SY. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet. 2013;380:2095–2128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann JJ, Apter A, Bertolote J, Beautrais A, Currier D, Haas A, Hegerl U, Lonnqvist J, Malone K, Marusic A, Mehlum L, Patton GC, Phillips M, Rutz W, Rihmer Z, Schmidtke A, SHAFFER D, Silverman MM, Takahashi Y, Varnik A, Wasserman D, Yip PS, Hendin H. Suicide prevention strategies: a systematic review. JAMA. 2005;294:2064–2074. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.16.2064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National health and medical research council. Australian guidelines to reduce health risks from drinking alcohol. N.H.M.R.C; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Neeleman J, de Graaf R, Vollebergh W. The suicidal process; prospective comparison between early and later stages. J Affect Disord. 2004;82:43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell KE, Kresnow M, Mercy JA, Potter LB, Swann AC, Frankowski RF, Lee RK, Bayer TL. Alcohol consumption and nearly lethal suicide attempts. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2001;32:30–41. doi: 10.1521/suli.32.1.5.30.24208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash LL. Modern Epidemiology. 3. Philadelphia: Lippincott William & Wilkins; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Royston P, Ambler G, Sauerbrei W. The use of fractional polynomials to model continuous risk variables in epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol. 1999;28:964–974. doi: 10.1093/ije/28.5.964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher L, Oquendo MA, Richardson-Vejlgaard R, Makhija NM, Posner K, Mann JJ, Stanley BH. Effect of acute alcohol use on the lethality of suicide attempts in patients with mood disorders. J Psychiatr Res. 2009;43:901–905. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stata Corp LP. Stata Statistical Software. [Release 13.1] College Statio, TX: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Steenland K, Armstrong B. An overview of methods for calculating the burden of disease due to specific risk factors. Epidemiology. 2006;17:512–519. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000229155.05644.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor B, Irving HM, Kanteres F, Room R, Borges G, Cherpitel C, Greenfield T, Rehm J. The more you drink, the harder you fall: a systematic review and meta-analysis of how acute alcohol consumption and injury or collision risk increase together. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;110:108–116. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of the Surgeon General and National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention. National Strategy for Suicide Prevention: Goals and Objetives for Action. DC: HHS; 2012. pp. 1–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox A, Conner KR, Caine ED. Association of alcohol and drug use disorders and completed suicide: An empirical review of cohort studies. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;76S:S19. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global status report on alcohol and health. 2014. WHO; 2014. p. 292. [Google Scholar]

- Ye Y, Bond JC, Cherpitel CJ, Borges G, Monteiro M, Vallance K. Evaluating recall bias in a case-crossover design estimating risk of injury related to alcohol: data from six countries. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2013;32:512–518. doi: 10.1111/dar.12042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]