Abstract

Background

Yoga and physical exercise have been used as adjunctive intervention for cognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia (SZ), but controlled comparisons are lacking.

Aims

A single-blind randomised controlled trial was designed to evaluate whether yoga training or physical exercise training enhance cognitive functions in SZ, based on a prior pilot study.

Methods

Consenting, clinically stable, adult outpatients with SZ (n = 286) completed baseline assessments and were randomised to treatment as usual (TAU), supervised yoga training with TAU (YT) or supervised physical exercise training with TAU (PE). Based on the pilot study, the primary outcome measure was speed index for the cognitive domain of ‘attention’ in the Penn computerised neurocognitive battery. Using mixed models and contrasts, cognitive functions at baseline, 21 days (end of training), 3 and 6 months post-training were evaluated with intention-to-treat paradigm.

Results

Speed index of attention domain in the YT group showed greater improvement than PE at 6 months follow-up (p < 0.036, effect size 0.51). In the PE group, ‘accuracy index of attention domain showed greater improvement than TAU alone at 6-month follow-up (p < 0.025, effect size 0.61). For several other cognitive domains, significant improvements were observed with YT or PE compared with TAU alone (p < 0.05, effect sizes 0.30–1.97).

Conclusions

Both YT and PE improved attention and additional cognitive domains well past the training period, supporting our prior reported beneficial effect of YT on speed index of attention domain. As adjuncts, YT or PE can benefit individuals with SZ.

Keywords: cognition, physical exercise, RCT, schizophrenia, yoga

Introduction

Impaired cognition is a hallmark of schizophrenia (SZ) (1,2), with widespread impairments in cognitive domains predating the onset of psychosis (1,2). Cognitive dysfunction is correlated with functional outcome, and has economic and social ramifications (3,4). It increases stigma, adding to illness burden (5). Current pharmacologic treatments produce improvement in psychotic symptoms, but do not improve cognitive impairments substantially (6,7). Consequently, non-pharmacologic behavioural treatments are being designed and tested (1). Many of the current novel cognitive enhancement therapies (CET) comprise intensive, systematic individual training combined with medications (8). As yoga includes mindfulness training and physical exercise, it can also be considered a CET (8). Systematic studies indicate that the practice of yoga can improve spatial memory (9), attention and recall (10), reduce reaction times and increase accuracy in executive function tasks in a variety of settings (11). Yoga can also improve strategic planning (12), concentration and emotional function in non-psychiatric populations (13,14). Yoga training is feasible for individuals with psychotic disorders (15). Some randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of yoga indicated improvements in psychopathology and social cognition in SZ (16–19), although the benefits were variable (17,18,20). Like yoga, physical exercise is thought to benefit cognitive functions in persons with or without psychiatric disorders (21–26). The benefits of physical exercise for the former have been documented in large studies, as well as meta-analyses (27,28). Specific benefits of aerobic exercise for neurocognitive deficits among people with SZ are being described (29).

In an open treatment study, we evaluated accuracy and speed indices for eight cognitive domains in relation to adjunctive yoga training for patients with SZ and other disorders (15). We found significant improvement with regard to measures of cognition, after 21 days of adjunctive yoga training, in contrast to treatment as usual (TAU) (15). We selected attention as the primary outcome of interest and designed a randomised controlled trial (RCT) to test our hypothesis (30). As physical exercise is a component of yoga and can improve cognitive functions (25), it was unclear whether the observed beneficial effects of yoga were attributable to physical exercise training that was included in the yoga training. Therefore, we included adjunctive physical exercise training as well as TAU for comparators, along with adjunctive yoga training.

Methods

Study design

A single-blind RCT was implemented to investigate the effects of three interventions, namely TAU, supervised yoga training added to TAU (YT) and supervised physical exercise training added to TAU (PE). Based on our open trial, we chose speed index of attention domain as the primary outcome measure, and included speed and accuracy indices for other cognitive domains as secondary outcome measures (15). Equal numbers of participants were allocated to the three groups.

Hypotheses to test the primary and secondary objectives

Primary hypothesis

YT improves speed index of attention domain among patients with SZ.

Secondary hypotheses

Brief supervised YT improves both speed and accuracy indices of the following cognitive domains: abstraction and mental flexibility, face memory, spatial memory, spatial ability, working memory, sensorimotor, emotion among patients with SZ.

Study site

Department of Psychiatry, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Dr. Ram Manohar Lohia Hospital (RMLH), Delhi, India. RMLH is a large teaching general hospital funded by the Government of India that provides primary/tertiary care to patients from Delhi and surrounding areas free of charge. The majority belong to lower or middle socio-economic classes.

Participants and inclusion/exclusion criteria

Patients above 18 years of age who attended RMLH Psychiatry outpatient clinics from December 2010 to January 2014 were included. Clinically stable outpatients with a clinical diagnosis of SZ (DSM IV) residing in Delhi and willing to participate were referred by their psychiatrists to the RCT research team for assessment, including consensus diagnoses based on DSM IV criteria (30). We did not include patients with over 6 month’s history of substance abuse, or patients having any neurological or medical disorder that could deteriorate following yoga/physical exercise or that could confound a diagnosis of SZ. Persons who practiced yoga before enrolment were also excluded.

Assessments and outcome measures

Following written informed consent, a consensus diagnosis was established using DSM IV criteria, based on the Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies (DIGS), a semi-structured interview, and available information from medical records and informants (30). Cognitive functions were assessed with the University of Pennsylvania Computerized Neurocognitive Battery (Penn CNB) (31), a validated assessment tool that quantitatively estimates accuracy and speed of performance in cognitive domains known to be impaired in SZ. The Penn CNB incorporates computer-based assessment to minimise observer bias. The cognitive domains included here were accuracy and speed indices for (1) abstraction and mental flexibility; (2) attention; (3) face memory; (4) spatial memory; (5) spatial processing; (6) working memory; (7) sensorimotor dexterity; and (8) emotion processing (31). Z scores for the cognitive domains were standardised using data from a separate group of Indian control participants (15,32). At study entry, information about additional clinical, physical and social variables was also obtained (30). All evaluations, apart from the diagnostic workup and the demographic data were repeated at 21 days (end of training), 3 months and 6 months post-training. Standardised Z scores at all time points are presented in Supplementary Table 1.

Randomisation

Following informed consent and assessment for eligibility, the principal study investigator (T.B.) randomised participants to the YT, PE or TAU in blocks of 12, using an online randomisation program (http://www.randomization.com). Two block randomised lists were prepared in advance to enable age stratified randomisation: 18–30 years or older than 30 years. The age range was based on the mean age of SZ participants enrolled in our prior research studies (33,34). The randomisation lists were stored in a password-protected computer by TB, who did not collect outcome measures, administer any interventions or treat the participants.

Blinding

All recruiters and raters (who administered the cognitive evaluations) were blinded to participants’ intervention group status throughout the study. The outpatient intervention and appointment schedules for all patients were determined by the patients’ psychiatrists, who also remained blinded to the adjunctive intervention groups. The YT and PE instructors, who managed the research evaluation schedule for each participant, were not blinded. Due to the nature of the intervention, the participants could not be blinded to their intervention group assignment, but they were asked not to reveal their assignment to the raters or their therapists.

Intervention

Clinical intervention as usual continued for all study participants. The manualised interventions – YT or PE training – were provided by qualified instructors to groups of participants in 1-h sessions every day for 21 consecutive days, with the exception of Sundays and public holidays (30). YT comprised postures, breathing and weekly nasal cleansing as detailed (30,35) (see Supplementary Materials). The trainees were supervised during all training sessions, and participated willingly and regularly. PE included brisk walks, followed by jogging and directed aerobic exercises. The protocol of physical exercise was adopted from a published paper, that is, Duraiswamy et al. (35) and it is part of their Supplementary Material (35). Both YT and PE training were imparted in groups as far as possible to reduce cost. The number of participants trained at any time was one to five. One YT instructor and one PE instructor were imparting training separately. Blood pressure and heart rates were monitored. The participants were advised to continue TAU, YT or PE past the training period.

Monitoring compliance post-training

After 21 days of supervised training, the participants were provided with a yoga training booklet along with compliance charts and were instructed to continue practicing at home and keeping records. However, there was no further directed training. The compliance charts had a grid showing dates on the left and questions regarding times, duration and monitoring of yoga in the title row. Whenever the participant practiced yoga or exercise, s/he made a tick mark in the box in front of the date. The compliance charts were to be maintained by participants and their relatives. Compliance records were collected at 3 and 6 months follow-up. Those who failed to return the charts were considered conservatively as non-compliant.

Data and safety monitoring

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee at PGIMER-RMLH, and the Institutional Review Board, University of Pittsburgh. All participants were screened for any injury or condition that might interfere with YT/PE. All data were stored in password-protected computers and special password-protected databases. A Data Safety Monitoring Board of external experts was constituted and the progress of the project was monitored annually for the first 3 years and bi-annually for the following 2 years. The study was registered with the National Institute of Health registry, registration number NCT01879709. There was no provision for registering yoga/PE intervention trials in India at the time the trial began.

Sample size

Based on our prior study, we estimated that a sample of 234 participants had 85% power to detect changes in cognitive domains with small effect size (0.15) at α = 0.05 (15). We enrolled 340 participants to compensate for attrition.

Data analysis

Data were entered manually, double checked and all inconsistencies were rectified in consultation with research staff. Data were also scrutinised to identify out of range values that were examined and discrepancies corrected from source files. Cognitive function data recorded in the Penn CNB do not require manual data entry and were stored at the CNB database at the University of Pennsylvania; these data were retrieved twice to eliminate downloading errors. Distributions of variables were examined for normality and no transformations were needed.

The hypothesis testing was performed in two stages. The first set of comparisons consisted of ‘between-group’ comparisons, that is, changes in each cognitive domain were compared between the three intervention groups. The second set consisted of ‘within-group’ comparisons, that is, changes in each cognitive domain over time were investigated within each intervention group.

Between-group comparisons

With four time points, baseline (pre-training), 21 days (end of training), 3 and 6 months (post-training), we used a mixed model repeated measures analytical method to test our primary and secondary hypotheses. The model included group (YT, PE, TAU), time (baseline, 21 days, 3 months, and 6 months), time × group interaction, gender, age and head of household (HOH) occupation (a proxy for socio-economic status taken from the DIGS). We used SAS® software PROC MIXED (36). All hypotheses were tested using the ESTIMATE statement in PROC MIXED. Adjustments for multiple comparisons for the secondary hypotheses were performed using the Hochberg procedure (37). The primary hypothesis was not adjusted for multiple comparisons as it involved a single measure, namely ‘Speed index of attention domain’. Effect size estimates comprised of standardised regression coefficients of the contrast-specific dummy group variables from linear regressions estimated at each assessment point. The dependent variables were the changes of follow-up scores from the baseline scores. Age, gender and HOH occupation were used as covariates.

Within-group comparisons

For the three intervention groups (YT, PE, TAU), effect sizes for the changes in cognitive domains at different assessment points in relation to baseline values were calculated by Cohen’s d, adjusted for the covariates age, gender and HOH occupation. Changes from baseline were also examined from mixed model analysis.

Results

Study data

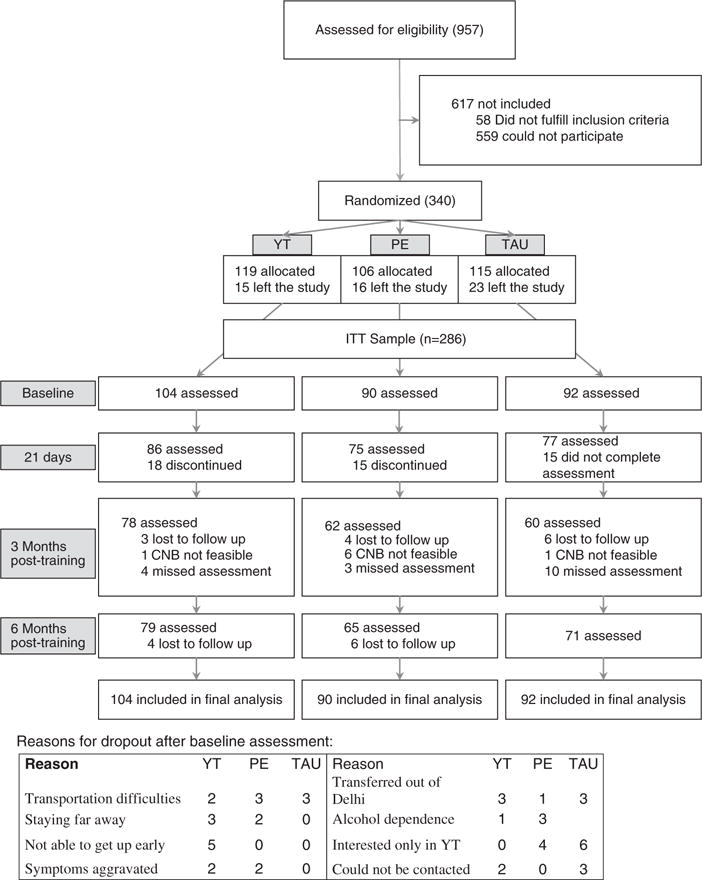

Out of 957 patients referred by RMLH psychiatrists, 340 were eligible based on detailed evaluations, inclusion criteria and consent to randomisation (Fig. 1). In total, 54 individuals withdrew from the study for personal reasons without any baseline assessments (YT 15, PE 16, TAU 23). The reasons for withdrawal included (i) relatives not available to come along as participants were unable to come alone (YT 3, PE 4, TAU 5); (ii) symptoms worsened (YT 4, PE 4, TAU 3); (iii) interested only in yoga; dropped out on finding they were not assigned to YT (PE 2; TAU 8); (iv) lost contact after randomisation. Thus, the intention-to-treat (ITT) sample consisted of 286 participants.

Fig. 1.

Study flow chart. CNB, Computerized Neurocognitive Battery; ITT, intention-to-treat; PE, supervised physical exercise training with TAU; TAU, treatment as usual; YT, supervised yoga training with TAU.

The reasons for dropout (n = 48) in the YT and PE groups included transportation difficulties (YT 2; PE 3; TAU 3), staying far away (YT 3; PE 2); not able to get up early (YT 5); symptoms aggravated (YT 2; PE 2); and being transferred out of Delhi (YT 3; PE 1; TAU 3). One YT and three PE participants were found to be dependent on alcohol following randomisation and were excluded from the study. Four PE participants later told that they were not interested in PE. Six participants in the TAU dropped out as they preferred YT. The other participants could not be contacted further. Participants were asked in an open format whether they had any problem during training and at follow-up points, none were reported.

Baseline characteristics

The baseline demographic, clinical and cognitive features are provided in Table 1. The sample included clinically stable individuals. We measured Scale for Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) and Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) scores for last 1 month at inclusion. The mean SAPS score was 12.08 (12.32). The mean SANS score was 24.14 (18.26). The participants were not symptomatic during training.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic, clinical and cognitive characteristics of the intention-to-treat sample

| Variables | YT (104) | PE (90) | TAU (92) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic variables | ||||

| Age (years) | 34.76 (9.56) | 35.20 (9.49) | 35.72 (10.06) | 0.79 |

| Gender (men/women) | 62/42 | 62/28 | 57/35 | 0.38 |

| Education in years of schooling† | 10.24 (4.05) | 9.38 (4.07) | 8.76 (4.54) | 0.05 |

| Married/not married | 51/53 | 51/39 | 55/37 | 0.26 |

| Occupation* | 2/3/9/90 | 0/1/7/82 | 0/3/6/83 | 0.60 |

| HOH occupation* | 6/23/23/52 | 4/14/15/57 | 7/12/11/62 | 0.16 |

| Clinical variables | ||||

| Total SAPS score | 12.44 (11.50) | 13.30 (12.93) | 10.52 (12.55) | 0.31 |

| Total SANS score | 23.58 (18.09) | 24.02 (18.10) | 24.82 (18.69) | 0.89 |

| Age at onset (years) | 24.88 (7.64) | 24.37 (7.24) | 25.48 (8.17) | 0.63 |

| Duration of illness in weeks | 440.99 (307.79) | 451.79 (307.91) | 444.37 (316.21) | 0.97 |

| Global Assessment of Functioning Score (past month) | 37.7 (14.87) | 36.73 (13.73) | 40.01 (16.54) | 0.33 |

| MMMSE score | 26.21 (6.01) | 25.91 (7.24) | 25.05 (7.25) | 0.50 |

| Cognitive domain Z scores | ||||

| Accuracy | ||||

| Abstraction and mental flexibility | −1.670 (0.656) | −1.72 (0.541) | −1.813 (0.606) | 0.28 |

| Attention | −1.049 (1.241) | −1.184 (1.432) | −1.101 (1.403) | 0.84 |

| Face memory | −0.709 (1.069) | −0.864 (1.320) | −1.001 (0.974) | 0.22 |

| Spatial memory† | −0.715 (0.928) | −0.754 (0.912) | −1.054 (1.009) | 0.03 |

| Working memory | −1.342 (1.119) | −1.556 (1.253) | −1.494 (1.247) | 0.48 |

| Spatial ability | −0.379 (0.882) | −0.372 (0.773) | −0.349 (0.704) | 0.98 |

| Sensorimotor | −0.172 (1.176) | −0.099 (1.098) | −0.371 (1.263) | 0.29 |

| Emotion† | −0.823 (0.931) | −1.019 (0.848) | −1.199 (0.836) | 0.02 |

| Speed | ||||

| Abstraction and mental flexibility | −0.756 (1.466) | −0.669 (0.902) | −0.801 (1.293) | 0.78 |

| Attention | −1.104 (1.926) | −1.092 (1.721) | −1.092 (1.412) | 0.10 |

| Face memory | −2.024 (5.306) | −1.689 (5.170) | −1.151 (2.939) | 0.45 |

| Spatial memory† | −0.630 (2.218) | −0.018 (1.789) | −0.073 (1.329) | 0.04 |

| Working memory | −0.587 (1.547) | −0.830 (1.432) | −0.998 (1.986) | 0.27 |

| Spatial ability | −1.512 (2.448) | −1.994 (2.297) | −1.608 (2.059) | 0.52 |

| Sensorimotor | −0.099 (1.021) | −0.071 (0.955) | −0.401 (1.863) | 0.19 |

| Emotion | −0.892 (2.337) | −0.740 (1.857) | −0.406 (1.600) | 0.25 |

HOH, head of the household; MMMSE, Modified Mini Mental State Examination from Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies (DIGS); PE, supervised physical exercise training with TAU; SANS, Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms; SAPS, Scale for Assessment of Positive Symptoms; TAU, treatment as usual; YT, supervised yoga training with TAU.

Continuous variables listed as mean (SD). Performance estimates for cognitive domains are listed as the mean (SD) of standardised Z scores as described in Methods section.

Occupations were considered under the following four categories, derived from the DIGS: managerial and professional specialty occupations; technical, sales and administrative support occupations; service occupations (household, protective); and all other occupations (farming, forestry, fishing, mechanic, construction, transportation, labourers, armed services, homemaker, student, unemployed, retired).

No significant difference after adjustment for multiple comparisons.

There were no statistically significant differences among participants in the three groups in the ITT sample following Bonferroni corrections for demographic, clinical as well as cognitive variables. There were no significant differences between those who completed the 21-day assessment (N = 238) and those who discontinued after baseline assessment or did not complete the 21-day assessment (N = 48) with regard to demographic, clinical and cognitive variables (Supplementary Table 2).

Missing values

We assumed all intermittently missing data, that is, individuals who missed a visit but came back for the next visit as ‘missing at random’ (MAR). Reasons for study dropouts, as detailed earlier and also given in Fig. 1, were personal, not related to earlier observations or covariates. Hence, dropouts were also considered as MAR.

Medications, substance abuse

The participants in the YT, PE and TAU groups did not differ significantly with regard to type of antipsychotic medication. The number of participants for whom the prescribed doses or types of antipsychotic drugs were changed during the training period or during follow-up did not vary between the intervention groups (data available with authors). There were no significant differences among three groups with regard to smoking status (Supplementary Table 3). The groups did not include any individuals who reported abusing alcohol or illicit substances during or 6 months before the study. Therefore, medications, smoking status or substance abuse were not used as covariates for subsequent analyses.

Between-group comparisons

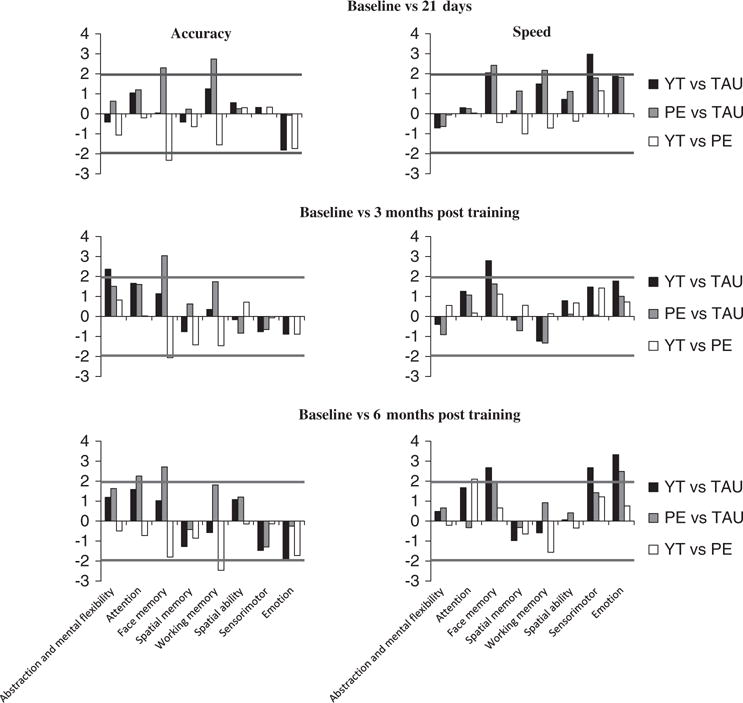

Comparisons of changes calculated from contrasts in cognitive domain scores from baseline between pairs of intervention groups are given in Fig. 2. The horizontal line at 1.96 mark shows statistically significant and non-significant contrasts. The statistically significant contrasts are given in Table 2 and are discussed below. The table includes contrast-specific uncorrected p-values and effect sizes. Contrasts that retained significance after correction for multiple hypothesis testing were marked in the table with a suffix and a footnote. Supplementary Table 4 provides a full list of all contrasts estimates, standard errors and uncorrected significance levels (p-values).

Fig. 2.

Comparisons of changes in cognitive domain scores from baseline between pairs of intervention groups. The X axis shows individual cognitive domains, with accuracy measures on the left and speed measures on the right. The Y axis shows t-values while comparing pairs of treatment groups. The statistical significance level is indicated by a horizontal line at 1.96. PE, supervised physical exercise training with TAU; TAU, treatment as usual; YT, supervised yoga training with TAU.

Table 2.

Statistically significant contrasts* between baseline and post-training assessments

| Assessment time point | Accuracy measures

|

Speed measures

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive domain | Contrast* | P | B† | Cognitive domain | Contrast* | P | B† | |

| 21 days | Face memory | PE > TAU | 0.020 | 0.44 | Face memory | PE > TAU | 0.016 | 1.90 |

| Working memory | PE > TAU | 0.006‡ | 0.63 | Spatial memory | YT > TAU | 0.003‡ | 1.07 | |

| Face memory | PE > YT | 0.020 | 0.53 | Working memory | PE > TAU | 0.030 | 0.70 | |

| Face memory | YT > TAU | 0.042 | 1.75 | |||||

| 3 months | Face memory | PE > TAU | 0.002‡ | 0.75 | Face memory | YT > TAU | 0.006‡ | 1.97 |

| Face memory | PE > YT | 0.039 | 0.41 | |||||

| Abstraction and mental flexibility | YT > TAU | 0.019 | 0.30 | |||||

| 6 months | Attention | PE > TAU | 0.025 | 0.61 | Attention | YT > PE | 0.036 | 0.51 |

| Face memory | PE > TAU | 0.007‡ | 0.52 | Emotion | PE > TAU | 0.013 | 0.87 | |

| Working memory | PE > YT | 0.014 | 0.52 | Emotion | YT > TAU | 0.001‡ | 0.95 | |

| Face memory | YT > TAU | 0.008‡ | 1.58 | |||||

| Spatial memory | YT > TAU | 0.008‡ | 0.79 | |||||

PE, supervised physical exercise training with TAU; TAU, treatment as usual; YT, supervised yoga training with TAU.

Contrasts were calculated from mixed model analysis with group (YT, PE, TAU), time (baseline, 21 days, 3 months and 6 months), time × group interaction, gender, age and head of the household (HOH) occupation. The p-values represent contrast significance levels.

Standardised regression coefficients of the contrast-specific dummy group variables from linear regressions were used as measures of effect sizes. The dependent variables were the changes of follow-up scores from the baseline scores and age, gender and HOH occupation as covariates.

Significant following Hochberg adjustment.

Test of the primary hypothesis

The speed index in the attention domain in the YT group showed greater improvement than the PE group at only 6-month follow-up (p < 0.036, effect size 0.51) (Table 2).

Tests of the secondary hypotheses

The significant results using uncorrected p-values (at p = 0.05) for contrasts comprising the secondary hypotheses are summarised below when the intervention groups were compared for the improvements from the baseline with different assessment time points (21 days, 3 months and 6 months) for the eight cognition domains (Table 2). For the speed index, the YT group performed significantly better than the TAU group for spatial memory (21 days, 6 months), face memory (21 days, 3 months and 6 months) and emotion (6 months). The PE group was significantly better than the TAU group with regard to face memory (21 days), working memory (21 days) and emotion (6 months). For the accuracy index, the PE group performed significantly better than TAU in several domains: face memory over the follow-up period (21 days, 3 months and 6 months), working memory (21 days) and attention (6 months). Improvements in the PE group were significantly greater than the YT group for face memory (21 days and at 3 months) and for working memory (6 months). The YT group improved significantly more than TAU for abstraction and mental flexibility at 3-month follow-up. Eight contrasts retained significance following Hochberg adjustments (37) for multiple comparisons for the seven correlated cognitive domains analysed in the secondary hypotheses (marked with a suffix in Table 2) and are detailed below.

Speed index

YT was better than TAU for spatial memory at 21 days and 6 months, YT was better than TAU for face memory at 3 months and 6 months, and YT was better than TAU for emotion at 6 months.

Accuracy index

PE was better than TAU for working memory at 21 days, PE was better than TAU for face memory at both 3 and 6 months.

In summary, our results showed that both interventions enhanced memory and attention over the follow-up, more so for the speed index.

Within-group changes over time

The accuracy index in the attention domain improved over the follow-up period in both YT and PE groups. For several other cognitive domains for both speed and accuracy indices, improvements were observed with YT and PE at all follow-up time points. Results from our mixed model analyses are in conformity with these findings (data not shown).

Clinical variables

We analysed SANS, SAPS and Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scores at every time point. We did not find any significant changes from baseline.

Compliance analysis

Compliance charts, filled by the patients and their relatives were returned by 75 (87%) YT and 59 (79%) PE participants at the 3-month assessment points and 75 (87%) YT and 64 (85%) PE participants at the 6-month assessment points. Compliance charts were unavailable from 27 participants at the 3-month assessment (YT 11; PE 16) and from 22 participants at the 6-month assessment (YT 11; PE 11). In YT group, 57% and 51% were compliant at 3 and 6 months, respectively, whereas in PE group 49% and 41% are compliant. There were no significant differences between the YT and PE groups with regard to the proportions of non-available data at both assessment time points. The compliance between the YT and PE groups was compared using the proportion of individuals who reported continuing the supplementations and those who did not report continuation for 3 months and 6 months post-training. No significant differences between the two groups were found in both periods considered. Compliance numbers are given in Supplementary Table 5.

Discussion

The trainees were supervised during all training sessions, and participated willingly and regularly. YT participants told the yoga instructor that yoga has made them more active. The relatives repeatedly enquired about any new programmes of YT after completion of the project also. So, we believe that YT and PE were well accepted by the participants. Compliance in both groups was satisfactory and no adverse effects were encountered in the study. The improvement in the speed index of attention domain with adjunctive YT supports the primary hypothesis generated from our earlier open, pilot trial (15,30). Consistent with our earlier study, YT improved other cognitive functions too. In agreement with earlier studies among individuals with or without SZ (28,38–43) persons who received PE training also showed significant improvement in several cognitive domains (including attention), although the pattern of improvement was different from the YT group. Similar to our study, Lin et al. (44) reported that yoga and aerobic exercise improved working memory in early psychosis patients, with yoga having a larger effect on verbal acquisition and attention than aerobic exercise. We used wider inclusion criteria – clinically stable outpatient with a clinical diagnosis of SZ. In contrast to the effects of YT and PE, cognitive functions did not change noticeably for the TAU group, discounting the possibility that the cognitive improvement with YT or PE was due solely to practice effects. The YT and PE benefits, while modest, are similar to encouraging results from other CETs that do not utilise physical exercise (8). The improvements with YT or PE might not be remarkable among healthy individuals, but they should be underscored for patients with SZ, among whom compliance can vary and among whom cognitive impairment is refractory to medications and worsens long-term prognosis (45,46).

In general, the cognitive domains that improved at the 21-day assessment showed continued improvement at the 3- and 6-month assessment points, supporting the notion of a sustained effect from the relatively brief interventions. Some domains, like abstraction and mental flexibility in the YT group and spatial memory in the PE group, showed statistically significant improvement only at the 6-month assessment, suggesting incremental improvement. The improvement in cognitive functions at the 6-month assessment with YT and PE is remarkable, as it was sustained during the unsupervised, post-training period, when compliance could be irregular. The sustained benefits of YT and PE have important therapeutic implications that justify the intensive supervised training.

There are several explanatory pathways for the improvement with YT and PE. Social stimulation, such as gathering in clubhouses can improve social and cognitive function (47), but it is unlikely to be the sole explanation, as the patterns of improvement differed in the YT and PE groups. Moreover, they were sustained beyond the training period. Some improvement with YT could be due to the physical exercise components of YT, but the pattern of changes differed between the YT and PE groups. Moreover, our YT protocol also included ‘pranayama’, a breathing technique that includes relaxation and meditation. Whether the pranayama itself or its combination with the physical exercises also contributed to the YT improvement is uncertain. We favour a combination of effects consistent with the holistic approach of the yoga philosophy, which promotes self-awareness, acceptance and the ability to be present in the moment.

The biological pathways that might mediate the beneficial effects are uncertain. Yoga elevates oxytocin levels, which can improve emotion recognition (19). YT also reduces cortisol levels and thus may have an indirect neuro protective action (48). A more substantial literature is available to explain the beneficial effects of PE, which improves stress coping mechanisms, multi-tasking abilities, information processing efficiency, as well as cardiovascular and metabolic health (21,22,26,27,49–52). PE is also reported to improve brain perfusion along with memory tasks (42) and could enhance neuronal plasticity (39–41). In mice, exercise can stimulate adult hippocampal neurogenesis resulting in improvement in learning and memory (53). To sum up, it is likely that several complementary mechanisms enable the beneficial effects.

Some limitations of the study should be noted. A double-blind trial was not feasible, though the single-blind design and the computerised cognitive assessment reduced observer bias. As the study was restricted to clinically stable outpatients and a substantial number of potential participants did not conform to inclusion criteria, further studies to test generalisability are needed. Face recognition test in the Penn CNB has western faces and empirical data regarding their use in Indian context is not available. Though lack of engagement or lack of sustained motivation could be a limiting factor for individuals with SZ (and engagement and motivation are required for the practice of yoga or physical exercise), the improvement available with either YT or PE provides greater choice. Finally, compliance past the training period was not assessed rigorously. The trajectory observed with some cognitive functions could arguably be improved if compliance was monitored more rigorously after the training period. We attempted to minimise bias by blinding, randomisation and concealment of allocation as suggested by Broderick et al. (20).

There are several avenues for future investigations. The sustained effects of YT and PE at the 6-month assessment points are intriguing and need to be explored further. In addition, modification of the YT and PE training modules, or combined YT and PE could provide further benefits. Alternatively, YT and PE could be evaluated in conjunction with other CETs. Wykes et al. (8) suggested that CETs should be combined strategically with planned psychiatric rehabilitation, an avenue that was not explored here. Whether YT or PE can benefit patients with unstable clinical status should also be explored. It may be necessary to adapt the PE and YT regimes for such individuals; for example, with alternate day training.

In conclusion, our RCT confirmed the improvement in the cognitive domain of attention noted with YT in individuals with SZ in our pilot trial. The trial also indicated sustained benefits of brief supervised YT and PE for several cognitive domains in the same individuals. Understanding the mechanism of the beneficial effects of these interventions may help individualise therapies.

Supplementary Material

Significant outcomes.

The RCT confirmed improvement in the speed index of attention cognitive domain after YT in individuals with schizophrenia.

Sustained benefits of brief supervised YT and PE were present for accuracy indices of face memory, abstraction and mental flexibility, and attention; and speed indices of face memory, attention, emotion and spatial memory in the trial participants.

Both interventions enhanced memory and attention over a 6 month’s follow-up period.

Limitations.

A double-blind trial was not feasible, though the single-blind design and the computerised cognitive assessment reduced observer bias.

As the study was restricted to clinically stable outpatients and a substantial number of potential participants did not conform to inclusion criteria, further studies to test generalisability are needed.

Compliance past the training period was not assessed rigorously.

Patients staying far away from the treatment facility could not be included in the study.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the members of our dedicated study team for their efforts: N.N. Mishra (PhD), Gyan Deepak Shah (MSc), Hemant Pande (MA, Yoga), Sreelatha S. Narayanan (MA), Deepak Malik (MPhil), Nupur Kumari (MPhil), Manoj Nandal (BPed, Physical Education) (Department of Psychiatry, PGIMER-Dr. RML Hospital, New Delhi, India). The authors also thank Dr. R.P. Beniwal (MD), Dr. Rahul Saha (MD), Dr. Shiv Prasad (MD), Dr. Shrikant Sharma (MD), Dr. Satnam Goyal (MD), Dr. Kiran Jakhar (MD), Dr. Mona Chowdhary (MD) and all other clinicians at the Department of Psychiatry, PGIMER-Dr. RML Hospital for referring the patients to the study. The authors thank our study consultants Dr. Rajesh Nagpal (MD) (Manobal Klinik, New Delhi, India) and Dr. S. N. Pande (PhD) (Indira Gandhi Technological and Medical Sciences University, Ziro, Arunachal Pradesh, India). The authors would like to thank DSMB members Dr. W. Selvamurthy, Prof. R. Ganguli, Dr. V. Srieenivas, Dr. J. Brar, Dr. A. Balsavar. The authors gratefully thank Sue Clifton (ME) (University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, WPIC, Pittsburgh, USA) for her editorial assistance. The authors are deeply grateful to our participants and families for their sincere participation.

Financial Support

The work was supported by the Fogarty International Center, the NIH Office of the Director Office of Behavioral and Social Science Research and the National Center for Chinese and Alternative Medicine, of NIH (R01TW008289) to T.B.; and Tri National Training Program in Psychiatric Genetics (TW008302) to V.L.N. and S.N.D.; and NIH funded grant A Neurobehavioral Family Study of Schizophrenia to V.L.N. (MH63480-06A). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIH. Fogarty International Center, NIH had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; preparation, review or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Appendix 1

Table A1.

Yoga Protocol

| Types of techniques | ||

|---|---|---|

| Chanting | Aum chanting 5 times | |

| Breathing exercises | Neck in normal position Neck in extended position Neck in flexed position |

Inhale and exhale forcefully with sound 5 times each in the mentioned positions |

| Warming/loosening exercises | ||

| Neck movement | 1. Up (backwards) 2. Down (forwards) |

Stretch your neck backwards as much as possible |

| 1. Centre to right 2. Centre to left |

Move your neck towards right shoulder then to centre and vice versa | |

| Rotation of neck 1. Clockwise 2. Anti-clockwise |

Rotate your neck first in clockwise, then in counter clockwise direction five times | |

| Shoulder joint movements | 1. Clockwise 2. Anti-clockwise |

Bend your elbow, place your fingers over your shoulders, then rotate your elbow in clockwise and counter clockwise directions |

| Finger strengthening exercise (to increase the power of fingers) | Keep your upper limbs straight forward at shoulder level, slightly flex your finger now with inhalation and use your whole internal muscular power to pull your hands towards your shoulders | |

| Knee joint exercise | Knee joint movements Up and down | Place both the hands over your knees and slightly bend them. Now move down and get up repeatedly |

| Rotation clockwise and anti-clockwise | Place both the hands over your knees and slightly bend them. Now rotate your knees in clockwise and anti-clockwise direction | |

| Standing postures | Kati chakrasan | Stand erect, stretch your arms forward at shoulder level and twist your spine right and left |

| Tadasan | Stand erect, stretch your arms upward, palms facing sideways now stand over toes | |

| Trikonasan | Stand erect, stretch your arms sideways at shoulder level, parallel to ground. Now bend your spine sideways right and left | |

| Supine lying postures | Savasana | Lie down in supine lying posture keep your legs apart at about one to one and half foot distance, in the same way keep your hands apart, palms facing upwards, keep your head in a comfortable position, and relax |

| Uttanpadasan | Lie down over your back, keep your legs together and arms by the side of your body with palms facing downwards. Now as you inhale lift both the legs up by 90° | |

| Naukasan | In supine lying position, lift your upper and lower part of the body up till 30° while inhaling, maintain your body weight on lower back | |

| Pawanmuktasan (ardha and poorna) | In supine lying position fold your legs at knee joint, then press both the knees against chest with both the hands. Now touch your chin or forehead with your knees | |

| Prone lying postures | Makarasan | Lie down in prone position, with legs apart and heels facing each other, place your palms over each other just under the forehead and rest your forehead on palms |

| Bhujangasan | Lie down on abdomen in prone position with legs together, place your palms beside your chest then slowly sift your forehead, shoulder, chest and abdomen till naval region | |

| Shalabhasan | Lie down in prone position with legs together, place your chin firmly over the ground then place your hands underneath of your thighs. Now as you inhale, lift both your legs up | |

| Dhanurasan | Lie down in prone position, bend your knees and catch hold of lower legs with hands, with inhalation lift your upper & lower body up, maintain whole body weight over abdomen | |

| Sitting postures | Pashimottanasan | In straight leg sitting posture keep your back straight and legs together, inhale and lift your hands up, now with exhalation bend forward at lower back so that you can catch hold your toes and touch your forehead with knees |

| Ushtrasan | Stand in a kneeing position keep your knees and feet 4 inches apart, arc your back backward, keep your palms over your heels | |

| Gomukhasan | Sit in long stretch sitting pose, bend your one leg at knee joint and cross it under the other leg and try to sit on heel. Repeat the same with the other leg. Take one of your hand back(same hand on which side knee is up), up from the shoulder and other hand back from the down, now catch hold your both hand behind your back | |

| Aradh matsyendrasan | Sit in long stretch sitting pose, bend your one leg at knee joint from underneath of other leg and keep its heel by the side of hip joint on opposite side. Same way bend your another leg at knee joint keep its heel beside the knee joint of other leg. Now, take opposite hand (opposite from the leg which is standing) encircle it against the leg which is standing, catch hold its foot and twist your spine back and keep your another hand on middle back | |

| Vajrasana | Sitting in long stretch sitting pose bend your one leg at knee joint and try to sit on its heel and same way bend your another leg at knee joint and sit on its heels | |

| Pranayamas | Nadhishuddhi | Sit in a comfortable position either crossed legs 7 vajrasana and padmasana. Keep your back and neck erect, make pranayam mudra from right hand. Now inhale from both nostril exhale from left inhale from left nostril, exhale from right and then inhale from right exhale from left and continue |

| Shitali | Sit in any comfortable position as before now protrude your tongue out and fold it from side to make a tube, inhale through this tube then take your tongue in and close your mouth, exhale from nose | |

| Bhramari | Sit in any comfortable position as before now inhale deeply, plug your ears with thumbs, place rest of the fingers softly on eyes. Now exhale from nose by producing honey bee sound | |

| Jalneti | Cleaning process of nostrils (once a week) | Stand with legs apart, lean forward at the angle of 60°s turn your neck on one side, place the nasal of neti pot filled with warm saline water on upper nostril, open your mouth and start inhalation and exhalation so that water comes out from the other nostril automatically. Perform kapalbhati after this |

| Prayer | After all the practices sit in sukhasan and then shanti mantra (sarve bhavantu sukhinah) |

Footnotes

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/neu.2016.42

References

- 1.Green MF, Harvey PD. Cognition in schizophrenia: past, present, and future. Schizophr Res Cogn. 2014;1:e1–e9. doi: 10.1016/j.scog.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meier MH, Caspi A, Reichenberg A, et al. Neuropsychological decline in schizophrenia from the premorbid to the postonset period: evidence from a population-representative longitudinal study. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171:91–101. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12111438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abouzaid S, Jutkowitz E, Foley KA, Pizzi LT, Kim E, Bates J. Economic impact of prior authorization policies for atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia. Popul Health Manag. 2010;13:247–254. doi: 10.1089/pop.2009.0063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Willis M, Svensson M, Lothgren M, Eriksson B, Berntsson A, Persson U. The impact on schizophrenia-related hospital utilization and costs of switching to long-acting risperidone injections in Sweden. Eur J Health Econ. 2010;11:585–594. doi: 10.1007/s10198-009-0215-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Millier A, Schmidt U, Angermeyer MC, et al. Humanistic burden in schizophrenia: a literature review. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;54:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kopelowicz A, Liberman RP. Integrating treatment with rehabilitation for persons with major mental illnesses. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54:1491–1498. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.11.1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunlop J, Brandon NJ. Schizophrenia drug discovery and development in an evolving era: are new drug targets fulfilling expectations? J Psychopharmacol. 2015;29:230–238. doi: 10.1177/0269881114565806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wykes T, Huddy V, Cellard C, Mcgurk SR, Czobor P. A meta-analysis of cognitive remediation for schizophrenia: methodology and effect sizes. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:472–485. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10060855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garfinkel MS, Schumacher HR, JR, Husain A, Levy M, Reshetar RA. Evaluation of a yoga based regimen for treatment of osteoarthritis of the hands. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:2341–2343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nangia D, Malhotra R. Yoga, cognition and mental health. J Indian Acad Appl Psychol. 2012;38:262–269. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gothe N, Pontifex MB, Hillman C, Mcauley E. The acute effects of yoga on executive function. J Phys Act Health. 2013;10:488–495. doi: 10.1123/jpah.10.4.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tran MD, Holly RG, Lashbrook J, Amsterdam EA. Effects of hatha yoga practice on the health-related aspects of physical fitness. Prev Cardiol. 2001;4:165–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1520-037x.2001.00542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berger BG, Owen DR. Mood alteration with yoga and swimming: aerobic exercise may not be necessary. Percept Mot Skills. 1992;75:1331–1343. doi: 10.2466/pms.1992.75.3f.1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pilkington K, Kirkwood G, Rampes H, Richardson J. Yoga for depression: the research evidence. J Affect Disord. 2005;89:13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhatia T, Agarwal A, Shah G, et al. Adjunctive cognitive remediation for schizophrenia using yoga: an open, non-randomized trial. Acta neuropsychiatr. 2012;24:91–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5215.2011.00587.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vancampfort D, Vansteelandt K, Scheewe T, et al. Yoga in schizophrenia: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;126:12–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2012.01865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balasubramaniam M, Telles S, Doraiswamy PM. Yoga on our minds: a systematic review of yoga for neuropsychiatric disorders. Front Psychiatry. 2012;3:117. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2012.00117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cramer H, Lauche R, Klose P, Langhorst J, Dobos G. Yoga for schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:32. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jayaram N, Varambally S, Behere RV, et al. Effect of yoga therapy on plasma oxytocin and facial emotion recognition deficits in patients of schizophrenia. Indian J Psychiatry. 2013;55(Suppl. 3):S409–S413. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.116318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Broderick J, Knowles A, Chadwick J, Vancampfort D. Yoga versus standard care for schizophrenia (review) In: The Cochrane Collaboration, JohnWiley & Sons Ltd, editor. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015. article no.: CD010554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dishman RK, Berthoud HR, Booth FW, et al. Neurobiology of exercise. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14:345–356. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stein DJ, Collins M, Daniels W, Noakes TD, Zigmond M. Mind and muscle: the cognitive-affective neuroscience of exercise. CNS Spectr. 2007;12:19–22. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900020484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vaynman S, Gomez-Pinilla F. Revenge of the ‘sit’: how lifestyle impacts neuronal and cognitive health through molecular systems that interface energy metabolism with neuronal plasticity. J Neurosci Res. 2006;84:699–715. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baker LD, Frank LL, Foster-Schubert K, et al. Aerobic exercise improves cognition for older adults with glucose intolerance, a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;22:569–579. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malchow B, Reich-Erkelenz D, Oertel-Knochel V, et al. The effects of physical exercise in schizophrenia and affective disorders. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013;263:451–467. doi: 10.1007/s00406-013-0423-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knochel C, Oertel-Knochel V, O’Dwyer L, et al. Cognitive and behavioural effects of physical exercise in psychiatric patients. Prog Neurobiol. 2012;96:46–68. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ten Have M, DE Graaf R, Monshouwer K. Physical exercise in adults and mental health status findings from the Netherlands mental health survey and incidence study (NEMESIS) J Psychosom Res. 2011;71:342–348. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gorczynski P, Faulkner G. Exercise therapy for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36:665–666. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kimhy D, Vakhrusheva J, Bartels MN, et al. The impact of aerobic exercise on brain-derived neurotrophic factor and neurocognition in individuals with schizophrenia: a single-blind, randomized clinical trial. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41:859–868. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbv022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bhatia T, Mazumdar S, Mishra NN, et al. Protocol to evaluate the impact of yoga supplementation on cognitive function in schizophrenia: a randomised controlled trial. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2014;26:280–290. doi: 10.1017/neu.2014.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gur RC, Ragland JD, Moberg PJ, et al. Computerized neurocognitive scanning: II. The profile of schizophrenia Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25:777–788. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00279-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gur RC, Richard J, Hughett P, et al. A cognitive neuroscience-based computerized battery for efficient measurement of individual differences: standardization and initial construct validation. J Neurosci Methods. 2010;187:254–262. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2009.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thomas P, Bhatia T, Gauba D, et al. Exposure to herpes simplex virus, type 1 and reduced cognitive function. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47:1680–1685. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bhatia T, Garg K, Pogue-Geile M, Nimgaonkar VL, Deshpande SN. Executive functions and cognitive deficits in schizophrenia: comparisons between probands, parents and controls in India. J Postgrad Med. 2009;55:3–7. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.43546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Duraiswamy G, Thirthalli J, Nagendra HR, Gangadhar BN. Yoga therapy as an add-on treatment in the management of patients with schizophrenia – a randomized controlled trial. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007;116:226–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.The SAS system for Windows. Release 9.2 [program] 9.2 version. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blakesley RE, Mazumdar S, Dew MA, et al. Comparisons of methods for multiple hypothesis testing in neuropsychological research. Neuropsychology. 2009;23:255–264. doi: 10.1037/a0012850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Forbes D, Thiessen EJ, Blake CM, Forbes SC, Forbes S. Exercise programs for people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;12:CD006489. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006489.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cotman CW, Berchtold NC. Exercise: a behavioral intervention to enhance brain health and plasticity. Trends Neurosci. 2002;25:295–301. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(02)02143-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Draganski B, Gaser C, Busch V, Schuierer G, Bogdahn U, May A. Neuroplasticity: changes in grey matter induced by training. Nature. 2004;427:311–312. doi: 10.1038/427311a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pereira MA, Rifas-Shiman SL, Kleinman KP, Rich-Edwards JW, Peterson KE, Gillman MW. Predictors of change in physical activity during and after pregnancy: project viva. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32:312–319. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Massin MM. The role of exercise testing in pediatric cardiology. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2014;107:319–327. doi: 10.1016/j.acvd.2014.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Strassnig MT, Signorile JF, Potiaumpai M, et al. High velocity circuit resistance training improves cognition, psychiatric symptoms and neuromuscular performance in overweight outpatients with severe mental illness. Psychiatry Res. 2015;229:295–301. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lin J, Chan Skw, Lee Ehm, et al. Aerobic exercise and yoga improve neurocognitive function in women with early psychosis. NPJ Schizophr. 2015;1:15047. doi: 10.1038/npjschz.2015.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arango C, Amador X. Lessons learned about poor insight. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37:27–28. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arango C, Bartko JJ, Gold JM, Buchanan RW. Prediction of neuropsychological performance by neurological signs in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1349–1357. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.9.1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cowell AJ, Pollio DE, North CS, Stewart AM, Mccabe MM, Anderson DW. Deriving service costs for a clubhouse psychosocial rehabilitation program. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2003;30:323–340. doi: 10.1023/a:1024085200791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rao NP, Varambally S, Gangadhar BN. Yoga school of thought and psychiatry: therapeutic potential. Indian J Psychiatry. 2013;55(Suppl. 2):S145–S149. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.105510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vancampfort D, DE Hert M, Knapen J, et al. State anxiety, psychological stress and positive well-being responses to yoga and aerobic exercise in people with schizophrenia: a pilot study. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33:684–689. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2010.509458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yaguez L, Shaw KN, Morris R, Matthews D. The effects on cognitive functions of a movement-based intervention in patients with Alzheimer’s type dementia: a pilot study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26:173–181. doi: 10.1002/gps.2510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Malchow B, Schmitt A, Falkai P. Physical activity in mental disorders. MMW Fortschr Med. 2014;156:41–43. doi: 10.1007/s15006-014-0044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Duman RS. Neurotrophic factors and regulation of mood: role of exercise, diet and metabolism. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26(Suppl. 1):88–93. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Van Praag H, Shubert T, Zhao C, Gage FH. Exercise enhances learning and hippocampal neurogenesis in aged mice. J Neurosci. 2005;25:8680–8685. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1731-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.