Abstract

Coronary artery ectasia (CAE) is one of the uncommon cardiovascular disorders. Its incidence ranges from 1.2%-4.9%. Coronary artery ectasia likely represents an exaggerated form of expansive vascular remodeling (i.e. excessive expansive remodeling) in response to atherosclerotic plaque growth with atherosclerosis being the most common cause. Although, it has been described more than five decades ago, its management is still debated. We therefore reviewed the literature until date by searching PubMed and Google scholar using key words “coronary artery ectasia”, “coronary artery aneurysm”, “pathophysiology”, “diagnosis”, “management” either by itself or in combination. We reviewed the full articles and review articles and focused mainly on pathophysiology, diagnosis and management of CAE.

Keywords: Coronary artery ectasia, coronary artery aneurysm, pathophysiology, diagnosis and management

Introduction

Coronary artery ectasia (CAE) or coronary artery aneurysm is the aneurysmal dilatation of coronary artery. It is defined as a dilatation with a diameter of 1.5 times the adjacent normal coronary artery based on CASS registry [1]. Its prevalence ranges from 1.2%-4.9% [2] with male to female ratio of 3:1 [2, 3]. The prevalence of CAE and comorbidities in the various studies are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Prevalence of CAE and comorbidities.

| Study | Total no. of cases | Cases of ectasia | Prevalence of CAE | HTN | DM | Hyperlipidemia | Coexistent CAD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Swaye et al. [1] | 20067 | 978 | 4.9% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| G Hartnell et al. [2] | 4993 | 70 | 1.4% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Harikrishnan S et al. [4] | 3200 | 144 | 4.5% | 45.4% | 27.2% | 90.9% | 84.7% (122 of 144 Cases) |

| Y Gunes, et al. [5] | 8812 | 122 | 1.38% | 47.5% | 16.4% | 54.9% | 59% |

| Lam et al. [6] | 8641 | 104 | 1.2% | 58% | 31% | 63% | 82% |

| Mohammed Atiq Almansori et al. [7] | 1115 | 67 | 6% | 64% | 59% | 59% | N/A |

N/A-not available

It is commonly classified based on the shape and the extent of involvement of coronary arteries.

Classification based on shape:

Saccular-transverse diameter is greater than the longitudinal dimension.

Fusiform-transverse diameter less than the longitudinal dimension.

Markis et al. [3] has classified CAE into four types (Table 2).

Table 2.

Classification based on extent of involvement.

|

Type 1 Diffuse ectasia with aneurysmal lesions in two vessels. Type 2 Diffuse ectasia in one vessel and discrete ectasia in another. Type 3 Diffuse ectasia in one vessel. Type 4 Discrete ectasia in one vessel. |

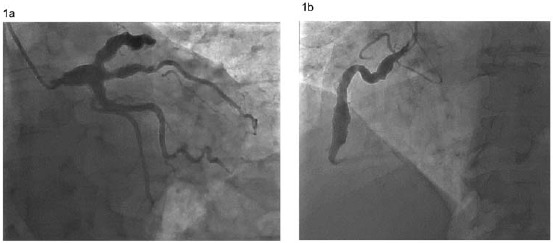

The proximal and middle segments of the right coronary artery (RCA) are the most common sites for CAE (68%) followed by the proximal left anterior descending (LAD) (60%) and the left circumflex arteries (LCx) (50%). Coronary artery ectasia of the left main (LMCA) is rare and occurs in only 0.1% of the population [1, 8]. Figures 1a and 1b shows the coronary artery ectasia on a coronary angiogram.

Fig. (1).

Coronary angiogram showing ectasia of the left main coronary artery, left anterior descending artery, ramus intermedius, proximal left circumflex (a) and right coronary artery (b).

Etiology

Congenital and acquired causes of CAE have been described below in Table 3. Atherosclerosis is the most common etiology [9].

Table 3.

Causes of coronary artery ectasia.

| Causes | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Congenital: frequently associated with other cardiac abnormalities such as bicuspid aortic valve, aortic root dilatation, ventricular septal defect or pulmonary stenosis. | Rare |

| Acquired: | |

| 1. Atherosclerosis | 50% |

| 2. Kawasaki disease and congenital causes | 17% |

| 3. Mycotic and infectious septic emboli including syphilis and borreliosis | 11% |

| 4. Connective tissue diseases and Marfan’s syndrome | <10% |

| 5. Arteritis, e.g., polyarteritis nodosa, Takayasu’s disease, systemic lupus erythematosus | <10% |

| 6. Iatrogenic, e.g., PTCA, stents, directional coronary atherectomy, angioplasty, and laser angioplasty | Rare |

| 7. Primary cardiac lymphoma | Rare |

PATHOGENESIS

Coronary artery aneurysm form as a result of interaction of various pathologic mechanisms which are summarized in the Fig. 2 [10].

Fig. (2).

Pathogenesis of coronary artery ectasia. RAS-Renin Angiotensin system. A number of factors implicated in the atherosclerotic process promote the expression and activity of matrix degrading enzymes, which cause severe disruption in the internal elastic lamina (IEL) and provide a gateway for the inflammatory cells to extend into the media, favoring excessive expansive remodeling and ultimately leading to formation of coronary ectasia. Adapted with permission from A.P. Antoniadis et al. [6].

Hypothesis of Remodeling

Coronary ectasia likely represents an exaggerated form of expansive vascular remodeling (i.e. excessive expansive remodeling) in response to atherosclerotic plaque growth. A variety of factors described below effect the enzymatic degradation of the extracellular matrix of the media which appears to be a fundamental pathologic process [10]. Proteolytic enzymes such as cysteine proteinases (e.g. cathepsins K, L, and S) and serine proteinases (e.g. neutrophil elastase, plasminogen activators, plasmin, chymase and tryptase) also play an important role in the pathogenesis of coronary ectasia [11] .

Role of Various Factors

Elevated homocysteine levels may facilitate the degradation of the medial arterial layer by inducing serine proteinase activity in arterial smooth muscle cells, as well as by activating matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) 2 [10]. Hyperinsulinemia may exacerbate the remodeling process in the setting of coronary atherosclerosis by stimulating the proliferation and migration of vascular smooth muscle cells from the arterial media and interfering with extracellular matrix production [12]. Chlamydia pneumoniae has been implicated in the pathogenesis of the ectasia by producing heat shock protein 60 which regulates MMP enzymes [13]. Several factors involved in the atherosclerotic process, such as accumulation of lipoproteins into the intima, inflammatory cell infiltration, renin–angiotensin system activation and generation of oxidative stress leads to excessive expansive arterial remodeling. Increased levels of NO caused vasodilatation and increased expression of MMP resulting in ectasia [14]. Coronary hemodynamics, in particular low endothelial shear stress predisposes to atherosclerosis and formation of vulnerable plaque and aneurysm formation [15].

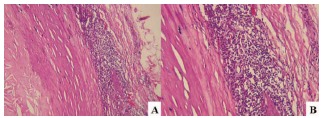

As a result of these processes, histological evaluation (Fig. 3) showed marked degradation of cystic medial

Fig. (3).

Histology of the left circumflex coronary artery aneurysm. A. Tunica intima expanded by atherosclerosis (left) and tunica media attenuated and densely infiltrated by inflammatory cells (right) (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification x10). B. Higher power showing the inflammatory cells to be predominantly lymphocytes, with a few residual smooth muscle cells (bottom center) (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification x20). Reproduced with permission from Nichols et al. [16].

degeneration and lymphohistiocytic infiltration in the tunica media [16]. Cystic medial degeneration was not present outside of the aneurysm.

Genetic factors have also been implicated in pathogenesis of CAE. Angiotensin converting enzyme DD genotype polymorphism seems to be a potent risk factor for the development of CAE [17] . Lamblin et al. showed that (MMP-3 5A) allele is associated with the occurrence of CAE [18]. Also, CAE is six times more frequent among patients with familial hypercholesterolemia than in a control group, suggesting a link between abnormal lipoprotein metabolism and aneurysmal coronary artery disease [19] .

Risk factors

CAE is more common in males. Hypertension is a risk factor [1]. Interestingly, patients with DM have low incidence of CAE. This may be due to down regulation of MMP with negative remodeling in response to atherosclerosis [20, 21] . Smoking appears to be more common in patients with CAE than in those with coronary artery disease (CAD). Cocaine use was also found to be an independent predictor of CAE irrespective of smoking [22] .

Clinical features

Stable angina is the most common presentation in patients with CAE [23] . Patients with CAE without stenosis had positive results during myocardial perfusion scintigraphic evaluation and treadmill exercise tests [24, 25] . In patients with isolated CAE, the extent of the ectasia and backflow phenomenon in an ectatic left anterior descending artery were identified as the most important angiographic predictors of ischemia on exercise testing [26] . ST-elevation myocardial infarction (MI) [27], non-ST elevation MI [28] can occur from altered blood flow [29, 30] by distal embolization or occlusion of ectatic segment with thrombus.

Complications such as thrombus formation, distal embolization, shunt formation and rupture can occur but the absolute risk is not known [31]. Coronary artery ectasia may also break through into the right atrium, right ventricle, or coronary sinus, creating left- to-right shunts.

Diagnosis

Coronary angiography has been diagnostic modality of choice until newer modalities like coronary Magnetic resonance angiogram (MRA) and coronary computed tomography angiogram (CTA) has become available. Angiography shows disturbances in blood flow filling and washout, which are associated with the severity of ectasia. Angiographic signs of turbulent and stagnant flow include delayed antegrade dye filling, a segmental back flow phenomenon, and local deposition of dye in the dilated coronary segment.

Coronary MRA has been shown to be equal to quantitative coronary angiography with the additional advantage of being a noninvasive technique [32, 33]. Coronary MRA may offer further valuable information, when complemented with coronary flow data, about the possibility of thrombotic occlusion of the aneurysmal vessels. Additionally MRA, being a noninvasive, non-radiating technique, can be used efficiently for follow up of these patients.

Coronary CTA is another noninvasive modality used to diagnose CAE [34]. Coronary CTA can be suggested as a technique of choice for the follow up of patients because of improvements in terms of radiation dose with the current protocols.

Intra vascular ultra sound (IVUS) is an excellent tool for assessing luminal size and characterizing arterial wall changes. IVUS correctly differentiates true from false aneurysms caused by plaque rupture. Emptied plaque cavities may appear angiographically as CAE and the distinction is of clinical importance, as false aneurysms may lead to acute coronary syndromes [35].

Management

Management is similar to that of CAD with few exceptions. It includes medical, angioplasty with stent and surgical modalities.

Medical management

It is a controversial area as there is lack of evidence based medicine. Aspirin was suggested in all patients because of coexistence of CAE with obstructive coronary lesions in the great majority of patients and the observed incidence of myocardial infarction, even in patients with isolated coronary ectasia [36]. The role of combined antiplatelet therapy, with the addition of adenosine diphosphate inhibitors, has not yet been evaluated in prospective randomized studies. It has been shown that plasma levels of P-selectin, beta thromboglobulin and platelet factor 4 are elevated in isolated CAE patients when compared with control participants who have angiographically normal coronary arteries, suggesting an increased platelet activation [37]. Based on the significant flow disturbances within the ectatic segments, chronic anticoagulation with warfarin as main therapy was suggested [38]. However, this treatment has not been tested prospectively, and could not be recommended unless supported by further studies and until then should be based on risk versus benefit [39].

Medications such as ACE inhibitors, statins may be useful in affecting the disease progression. Based on the association of ACE gene polymorphism and CAE, ACE inhibitors could be useful in the suppression of CAE progression, but this is yet to be proven [17]. Because elevated MMP-3 levels likely contribute to the development of coronary aneurysms, this matrix-degrading enzyme may represent an important therapeutic target. Statins could be beneficial by inhibiting MMP-3 activity, corticosteroids, IL-4 and by suppressing MMP expression [31, 40]. Administration of nitroglycerin and nitrate derivatives may induce angina pectoris in patients with CAE and should be avoided [41].

Percutaneous intervention (PCI)

In patients with coexisting obstructive lesions and symptoms or signs of significant ischemia despite medical therapy, PTCA can be done. Polytertafluoroethylene (PTFE)-covered, balloon-expandable stent has been shown to be an effective device for the percutaneous management and for exclusion of coronary aneurysms [42].

Surgery

In the symptomatic patient not suitable for PCI, surgical excision or ligation of the CAE combined with bypass grafting of the affected coronary arteries can be the procedure of choice [43]. Good outcomes has been demonstrated after these procedures [44].

Prognosis

Long-term prognosis and outcome in patients with CAE is unknown. In the CASS registry no difference in survival was observed between patients with or without CAE [1]. Several studies thereafter failed to show a mortality difference between CAE and CAD and concluded that CAE is a variant of atherosclerosis that confers no additional risk [2, 39, 45].

Conclusion

CAE incidence ranges from 1.2%-4.9%. It is a complex pathophysiological process involving the interaction of various pathways, in turn leading to excessive positive remodeling resulting in ectatic vessels. The prognosis is determined mainly by the severity of the coexisting obstructive CAD. Currently, there are no guidelines for treatment of CAE. Management is similar to that of CAD with few exceptions. Overall, management is hampered by lack of evidence. We need prospective studies and registries to further our knowledge in the management of this disorder.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Swaye P.S., Fisher L.D., Litwin P., et al. Aneurysmal coronary artery disease. Circulation. 1983;67(1):134–138. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.67.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartnell G.G., Parnell B.M., Pridie R.B. Coronary artery ectasia. Its prevalence and clinical significance in 4993 patients. Br. Heart J. 1985;54(4):392–395. doi: 10.1136/hrt.54.4.392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Markis J.E., Joffe C.D., Cohn P.F., Feen D.J., Herman M.V., Gorlin R. Clinical significance of coronary arterial ectasia. Am. J. Cardiol. 1976;37(2):217–222. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(76)90315-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harikrishnan S., Sunder K.R., Tharakan J., et al. Coronary artery ectasia: angiographic, clinical profile and follow-up. Indian Heart J. 2000;52(5):547–553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gunes Y., Boztosun B., Yildiz A., et al. Clinical profile and outcome of coronary artery ectasia. Heart. 2006;92(8):1159–1160. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.069633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lam C.S., Ho K.T. Coronary artery ectasia: a ten-year experience in a tertiary hospital in Singapore. Ann. Acad. Med. Singapore. 2004;33(4):419–422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Almansori M.A., Elsayed H.A. Coronary artery ectasia – A sample from Saudi Arabia. J. Saudi Heart Assoc. 2015;27(3):160–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jsha.2015.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elahi M.M., Dhannapuneni R.V., Keal R. Giant left main coronary artery aneurysm with mitral regurgitation. Heart. 2004;90(12):1430. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2004.036293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roberts W.C. Natural history, clinical consequences, and morphologic features of coronary arterial aneurysms in adults. Am. J. Cardiol. 2011;108(6):814–821. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Antoniadis A.P., Chatzizisis Y.S., Giannoglou G.D. Pathogenetic mechanisms of coronary ectasia. Int. J. Cardiol. 2008;130(3):335–343. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.05.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu J., Sukhova G.K., Yang J-T., et al. Cathepsin L expression and regulation in human abdominal aortic aneurysm, atherosclerosis, and vascular cells. Atherosclerosis. 2006;184(2):302–311. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson P.W., Zhang X.Y., Tian J., et al. Insulin and angiotensin II are additive in stimulating TGF-beta 1 and matrix mRNAs in mesangial cells. Kidney Int. 1996;50(3):745–753. doi: 10.1038/ki.1996.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kol A., Sukhova G.K., Lichtman A.H., Libby P. Chlamydial heat shock protein 60 localizes in human atheroma and regulates macrophage tumor necrosis factor-alpha and matrix metalloproteinase expression. Circulation. 1998;98(4):300–307. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.4.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johanning J.M., Franklin D.P., Han D.C., Carey D.J., Elmore J.R. Inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase limits nitric oxide production and experimental aneurysm expansion. J. Vasc. Surg. 2001;33(3):579–586. doi: 10.1067/mva.2001.111805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giannoglou G.D., Soulis J.V., Farmakis T.M., Farmakis D.M., Louridas G.E. Haemodynamic factors and the important role of local low static pressure in coronary wall thickening. Int. J. Cardiol. 2002;86(1):27–40. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(02)00188-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nichols L., Lagana S., Parwani A. Coronary artery aneurysm: a review and hypothesis regarding etiology. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2008;132(5):823–828. doi: 10.5858/2008-132-823-CAAARA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gülec S., Aras Ö., Atmaca Y., et al. Deletion polymorphism of the angiotensin I converting enzyme gene is a potent risk factor for coronary artery ectasia. Heart. 2003;89(2):213–214. doi: 10.1136/heart.89.2.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lamblin N., Bauters C., Hermant X., Lablanche J-M., Helbecque N., Amouyel P. Polymorphisms in the promoter regions of MMP-2, MMP-3, MMP-9 and MMP-12 genes as determinants of aneurysmal coronary artery disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2002;40(1):43–48. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01909-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sudhir K., Ports T.A., Amidon T.M., et al. Increased Prevalence of Coronary Ectasia in Heterozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia. Circulation. 1995;91(5):1375–1380. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.5.1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baugh M.D., Gavrilovic J., Davies I.R., Hughes D.A., Sampson M.J. Monocyte matrix metalloproteinase production in Type 2 diabetes and controls--a cross sectional study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2003;2:3. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-2-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kornowski R., Mintz G.S., Lansky A.J., et al. Paradoxic decreases in atherosclerotic plaque mass in insulin-treated diabetic patients. Am. J. Cardiol. 1998;81(11):1298–1304. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00157-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Satran A., Bart B.A., Henry C.R., et al. Increased prevalence of coronary artery aneurysms among cocaine users. Circulation. 2005;111(19):2424–2429. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000165121.50527.DE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aboeata A.S., Sontineni S.P., Alla V.M., Esterbrooks D.J. Coronary artery ectasia: current concepts and interventions. Front. Biosci. (Elite Ed.) 2012;4:300–310. doi: 10.2741/377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sayin T., Döven O., Berkalp B., Akyürek O., Güleç S., Oral D. Exercise-induced myocardial ischemia in patients with coronary artery ectasia without obstructive coronary artery disease. Int. J. Cardiol. 2001;78(2):143–149. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(01)00365-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saglam M., Karakaya O., Barutcu I., et al. Identifying cardiovascular risk factors in a patient population with coronary artery ectasia. Angiology. 2007;58(6):698–703. doi: 10.1177/0003319707309119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Altinbas A., Nazli C., Kinay O., et al. Predictors of exercise induced myocardial ischemia in patients with isolated coronary artery ectasia. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2004;20(1):3–17. doi: 10.1023/b:caim.0000013158.15961.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mrdović I., Jozić T., Asanin M., Perunicić J., Ostojić M. Myocardial reinfarction in a patient with coronary ectasia. Cardiology. 2004;102(1):32–34. doi: 10.1159/000077000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kühl M., Varma C. A case of acute coronary thrombosis in diffuse coronary artery ectasia. J. Invasive Cardiol. 2008;20(1):E23–E25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rath S., Har-Zahav Y., Battler A., et al. Fate of nonobstructive aneurysmatic coronary artery disease: angiographic and clinical follow-up report. Am. Heart J. 1985;109(4):785–791. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(85)90639-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Akyürek O., Berkalp B., Sayin T., Kumbasar D., Kervancioğlu C., Oral D. Altered coronary flow properties in diffuse coronary artery ectasia. Am. Heart J. 2003;145(1):66–72. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2003.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pahlavan P.S., Niroomand F. Coronary artery aneurysm: a review. Clin. Cardiol. 2006;29(10):439–443. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960291005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim W.Y., Danias P.G., Stuber M., et al. Coronary magnetic resonance angiography for the detection of coronary stenoses. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001;345(26):1863–1869. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mavrogeni S., Markousis-Mavrogenis G., Kolovou G. Contribution of cardiovascular magnetic resonance in the evaluation of coronary arteries. World J. Cardiol. 2014;6(10):1060–1066. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v6.i10.1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Díaz-Zamudio M., Bacilio-Pérez U., Herrera-Zarza M.C., et al. Coronary Artery Aneurysms and Ectasia: Role of Coronary CT Angiography. Radiographics. 2009;29(7):1939–1954. doi: 10.1148/rg.297095048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sanidas E.A., Vavuranakis M., Papaioannou T.G., et al. Study of atheromatous plaque using intravascular ultrasound. Hell J Cardiol HJC Hellēnikē Kardiologikē Epitheōrēsē. 2008;49(6):415–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.al-Harthi S.S., Nouh M.S., Arafa M., al-Nozha M. Aneurysmal dilatation of the coronary arteries: diagnostic patterns and clinical significance. Int. J. Cardiol. 1991;30(2):191–194. doi: 10.1016/0167-5273(91)90094-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yasar A.S., Erbay A.R., Ayaz S., et al. Increased platelet activity in patients with isolated coronary artery ectasia. Coron. Artery Dis. 2007;18(6):451–454. doi: 10.1097/MCA.0b013e3282a30665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sorrell V.L., Davis M.J., Bove A.A. Current knowledge and significance of coronary artery ectasia: a chronologic review of the literature, recommendations for treatment, possible etiologies, and future considerations. Clin. Cardiol. 1998;21(3):157–160. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960210304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Demopoulos V.P., Olympios C.D., Fakiolas C.N., et al. The natural history of aneurysmal coronary artery disease. Heart. 1997;78(2):136–141. doi: 10.1136/hrt.78.2.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tengiz I., Ercan E., Aliyev E., Sekuri C., Duman C., Altuglu I. Elevated levels of matrix metalloprotein-3 in patients with coronary aneurysm: A case control study. Curr. Control. Trials Cardiovasc. Med. 2004;5(1):10. doi: 10.1186/1468-6708-5-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krüger D., Stierle U., Herrmann G., Simon R., Sheikhzadeh A. Exercise-induced myocardial ischemia in isolated coronary artery ectasias and aneurysms (“dilated coronopathy”). J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1999;34(5):1461–1470. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00375-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fineschi M., Gori T., Sinicropi G., Bravi A. Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) covered stents for the treatment of coronary artery aneurysms. Heart. 2004;90(5):490. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2003.022749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Badmanaban B., Mallon P., Campbell N., Sarsam M.A. Repair of left coronary artery aneurysm, recurrent ascending aortic aneurysm, and mitral valve prolapse 19 years after Bentall’s procedure in a patient with Marfan syndrome. J. Card. Surg. 2004;19(1):59–61. doi: 10.1111/j.0886-0440.2004.02052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harandi S., Johnston S.B., Wood R.E., Roberts W.C. Operative therapy of coronary arterial aneurysm. Am. J. Cardiol. 1999;83(8):1290–1293. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00079-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Befeler B., Aranda M.J., Embi A., Mullin F.L., El-Sherif N., Lazzara R. Coronary artery aneurysms: study of the etiology, clinical course and effect on left ventricular function and prognosis. Am. J. Med. 1977;62(4):597–607. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(77)90423-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]