Abstract

In a previous study, target based screening was carried out for inhibitors of β-hematin (synthetic hemozoin) formation, and a series of triarylimidazoles were identified as active against Plasmodium falciparum. Here, we report the subsequent synthesis and testing of derivatives with varying substituents on the three phenyl rings for this series. The results indicated that a 2-hydroxy-1,3-dimethoxy substitution pattern on ring A is required for submicromolar parasite activity. In addition, cell-fractionation studies revealed uncommonly large, dose-dependent increases of P. falciparum intracellular exchangeable (free) heme, correlating with decreased parasite survival for β-hematin inhibiting derivatives.

Keywords: Antimalarial, Plasmodium falciparum, triarylimidazole, hemozoin

No new chemical classes of antimalarials have been introduced into clinical practice since 1996, and the shortage of novel, publicly accessible antimalarial scaffolds has had a negative impact on drug discovery efforts.1,2 Past and present therapies are based on a limited number of chemotypes (e.g., quinolines, cycloguanils, tetracylines, and sesquiterpene lactones), which often leads to cross-resistance.3 Target-based high throughput screening (HTS) of diverse libraries is a popular approach to identifying novel drug scaffolds and requires assays for inhibition of specific P. falciparum pathways. Hemozoin (Hz) inhibition is one such valid pathway, since this process is not directly affected by the structure-specific efflux mechanism, which causes chloroquine resistance in the parasite.4 Synthetic Hz, β-hematin (βH), can be efficiently and reliably synthesized in the laboratory with minimal equipment using a variety of methods.5−8 Furthermore, detecting the formation of βH is easily achieved through a number of spectroscopic techniques including IR,9 UV–vis of the dissolved crystals,10 or UV–vis of the ferrihemochrome complex formed between “free” Fe(III)PPIX and pyridine (free heme refers to non-Hz/βH, nonhemoglobin heme that coordinates to pyridine at pH ≈ 7).11,12 Several groups have endeavored to find novel βH inhibitors via target-based HTS projects.13−16 Most recently, a total of 144,330 compounds from the Vanderbilt University (VU) chemical compound library were screened for their ability to inhibit βH formation using an NP-40 based assay described previously and the ferrihemochrome method of detection.8,15,16 Of the 530 confirmed βH inhibitors, 171 inhibited parasite growth by ≥90% at 23 μM (32.3% of the 530 βH inhibitors) and 25 compounds exhibited favorable IC50 values below 1 μM. Furthermore, cell fractionation studies successfully validated Hz formation as the mechanism of action in parasites for a subset of tested compounds, which represented 12 of the 14 novel scaffolds identified. Dose-dependent measurements of intracellular free heme and Hz revealed that different levels of free heme were attained in the parasite, depending on compound type. Three compounds caused extraordinarily high levels of non-Hz free heme (30–50% of total heme) at 2.5 times their respective IC50 when compared to those seen with CQ and other quinoline-containing scaffolds (8–14%).17,18 Two of these compounds were benzamides, reported elsewhere,19 and the other, a triarylimidazole, which attained a free heme content of 43%. The triarylimidazole class also displayed a high hit rate for parasite activity, as six of seven βH inhibitors were active against P. falciparum (Table 1).

Table 1. Seven βH Inhibiting Triarylimidazoles from the HTS Active against P. falciparum(16).

Compounds are listed in order of decreasing D6 activity. The intracellular % free heme increase is shown in bold for 6.

Recently, in phenotypic screens carried out by GSK and Novartis several triarylimidazoles were discovered to have activity against the 3D7 strain of P. falciparum,1,20 and three triarylimidazoles in the MMV Malaria Box were reported as inhibitors of βH formation.21 Consequently, this scaffold was selected as interesting for investigating Hz inhibition of this class owing to the novelty of the chemotype. Furthermore, additional analysis of the HTS hits and their derivatives with potent βH inhibition activity, but with a range of parasite activities and intracellular free heme levels was required for an ongoing study into the mechanistic aspects of nonquinoline Hz inhibitors. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate a range of triarylimidazoles as probe compounds to gain a better understanding of the relationships between activity and levels of non-Hz free heme in the parasite. This involved identifying the pharmacophore and preliminary SARs for this series as a step toward exploring their mechanism of action and antimalarial potential.

Seven triarylimidazoles were found to inhibit parasite growth in the HTS, with three showing IC50 values below 1 μM.16 Interestingly all seven were very good βH inhibitors, at least twice as active as CQ, but parasite activity decreased significantly upon variation of the 3,5-dimethoxy-4-hydroxy substituents on ring A. The identified compounds showed D6 IC50s from 0.3 to 11.7 μM (Table 1), with small structural changes having significant influence on activity as evident when comparing 1 (0.3 μM), 3 (0.7 μM), 5 (2.4 μM), and 6 (9.0 μM).

The triarylimidazole scaffold was initially deconstructed in order to determine the minimum structural features for βH inhibition activity (Table 2). Rings B and C in the HTS hits appeared to have a less important influence on βH activity than ring A. As a result, rings B and C were removed to evaluate whether they are required. The monoarylimidazoles 2-phenylimidazole (8a) and 4-(1H-imidazol-2-yl)phenol (8b) were obtained commercially and tested in the NP-40 assay. Compound 8a was found to be entirely inactive against βH formation, while 8b showed only very weak activity, more than 10-fold less active than those possessing rings B and C, confirming that they are essential for potent activity. Additional data on the triarylimidazole chemotype, which was made available via a collaboration between UCT and Vanderbilt University (VU), indicated that the unsubstituted 2,4,5-triphenylimidazole (9) also did not inhibit βH formation.

Table 2. βH and D6 or NF54 and K1 parasite IC50 Values.

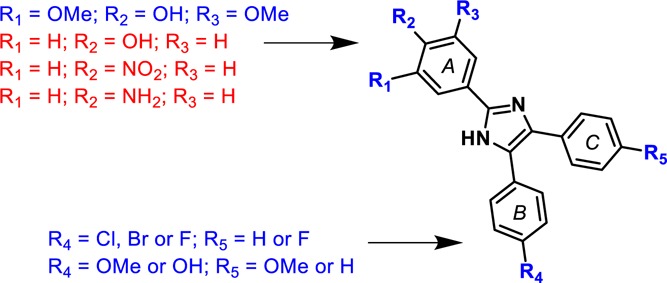

The next evaluated derivative was the purchased compound 4-(4,5-diphenyl-1H-imidazol-2-yl)phenol (10), which was identified as the simplest triphenylimidazole to strongly inhibit βH formation (IC50 of 17.7 μM). In order to further investigate the SARs for this scaffold, derivatives 14a–d were synthesized using the standard method available in the literature by refluxing the appropriate aldehyde, benzil, and sodium acetate in MeOH, according to Scheme 1. Target compounds 14e and 14f containing substituents on the B and C rings required 4-chlorobenzil (13e) and 4,4′-dimethoxybenzil (13f) as starting materials, respectively. Since these compounds were not commercially available at the time of synthesis, they were synthesized from the corresponding benzoins, 11e and 11f via oxidation of the hydroxyl to the carbonyl with sodium hydride and O2. Attempts to synthesize target compound 15 containing a para-amino group on the A-ring from p-aminobenzaldehyde were unsuccessful. It is likely that the aldehyde preferentially self-condenses under these conditions to give oligomeric products; however, this was not further investigated. An alternative route was followed whereby the nitro derivative (14g) was formed and then reduced to the amine using iron powder and a catalytic amount of HCl. The conditions reported by Wan et al.22 were followed for the formation of both 14g and 15, which involved a 4 h glacial acetic acid reflux at 118 °C for 14g and then a 6 h reflux at 80 °C with Fe powder in an EtOH/water (2:1) mixture to afford 15.

Scheme 1. Preparation of the Triarylimidazole Derivatives 14a–g and 15.

Compound 14a resembles the parent compound, 1, but lacks the bromo substituent on ring B. This derivative maintained potent activity against βH formation, confirming that the substituents on rings B and C are not essential. The substituents on ring A were varied by replacing the 4-hydroxy group with a methoxy group (14b) or a hydrogen atom (14c). These analogues also maintained activity against βH formation, demonstrating that with R1 = R3 = OMe, substituents at R2 are not required. By contrast, βH inhibition IC50 data for derivatives with R1 = R3 = H suggested that a substituent at R2 is necessary but not sufficient for activity. Specifically, analogues with R2= OH (10), NO2 (14g), and NH2 (15) were βH inhibitors, while those with R2= H (9) or OCF3 (14d) showed no inhibition up to 1000 μM. This indicated that compounds with both electron withdrawing and releasing groups as well as both planar and nonplanar substituents on ring A are tolerated. Finally, analogues of 14c, which contained either a 4-chloro atom on ring B (14e) or 4-methoxy groups on both rings B and C (14f) were evaluated as an indication of the influence of substituents on these rings. These compounds displayed similar activity to 14c, with IC50 values of 16.6 and 13.8 μM for the chloro and dimethoxy analogues, respectively. This also demonstrated that both electron withdrawing and releasing as well as planar and nonplanar substituents are tolerated on rings B and C. Replacing phenyl ring A with pyridyl, which corresponds to the active compound 16 from VU, gave a βH inhibition IC50 of 25.4 μM. The βH activity data for the triarylimidazoles are shown in Table 2.

Derivatives 8b and 9, which were not βH inhibitors below 100 μM, also showed no parasite activity up to 20 μM. Surprisingly, the other noninhibitor, 14d, showed a moderate activity of 4.2 μM. Derivative 16, which was a potent βH inhibitor, showed weak activity of 10.8 μM in the CQ-sensitive D6 strain. The remaining purchased and synthesized triarylimidazoles were tested in the LDH parasite growth inhibition assay using the CQ sensitive NF54 strain (Table 2). Compound 10 was found to be inactive at concentrations up to 32 μM, despite displaying potent βH activity. Other derivatives, which performed poorly in the assay, were the 4-nitro (14g) and 4-amino (15), analogues of 10. This showed that having substituents only in the para position of ring A was not sufficient for parasite activity. For the βH inhibiting compounds containing 3,5-methoxy groups on ring A, 14a–c, the parasite activity improved from 7.0 to 1.3 μM with variation of the para-R2 substituent H < OMe < OH, illustrating that the ring A substitution pattern of the parent compound (1, Table 1) was superior for activity. The ability of βH inhibiting derivatives with a greater number of hydroxyl and methoxy substituents to inhibit parasite growth can be seen graphically in Figure 1. This had a much greater impact on parasite activity than did βH inhibition IC50. Indeed, the relationship with βH activity was not statistically significant.

Figure 1.

Linear correlation between the log of the parasite activity with the number of hydroxyl or methoxy substituents on the phenyl rings in a triarylimidazole given by log(NF54 IC50) = −0.30(# of OH or OMe) + 1.23; (r2 = 0.76, P = 0.0048).

The most active triarylimidazoles in the HTS, with submicromolar activity, contained a para-Br or -OH substituent on ring B (Table 1), suggesting that the effect of these groups, while not a significant factor for βH inhibition, is to increase parasite activity. The preparation of 14e and 14f was carried out in order to determine whether the activity of triarylimidazoles with other ring A substituents could also be improved by attaching ring B and ring C substituents. The 4-chloro and 4,4′-dimethoxy analogues were tested and found to improve activity from 7.0 μM for 14c to ∼1.7 μM for both 14e and 14f. This >4-fold activity improvement upon the introduction of ring B and/or C substituents was almost identical to that of 14c vs 1 (Table 1). This trend was also observed when comparing 10 with poor activity (>32 μM) to its 4-bromo derivative 6 from the HTS, with IC50 of 9.1 μM. Compounds 14a, 14c, 14e, and 14f were selected for testing in the CQ-resistant K1 strain of P. falciparum and were found to have low resistance indices (RIs), indicating no significant CQ cross-resistance for this series. Furthermore, compounds 14c, 14f, and 14g showed low cytotoxicity against Chinese hamster ovarian (CHO) cells (>100 μM), demonstrating specific activity against the malaria parasite (Table 2 footnote c). By contrast, 14d was an order of magnitude more cytotoxic, with a selectivity index of only 7, suggesting that its activity against Plasmodium is likely based on its cytotoxicity. The SAR is summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Favorable (blue) and unfavorable (red) substituents for parasite activity within the triarylimidazole HTS hits and synthesized analogues.

The triarylimidazole 6 (Table 1) from the HTS was shown to cause an increase in non-Hz, nonhemoglobin “free” heme to 43% of total heme.16 Nevertheless, data for additional derivatives with a range of potencies were deemed necessary in order to support the biological mechanism of action for this series. Compounds 14c, 14f, and 14g, which had different ring A substituents from the HTS hits and showed a marked difference in activity, were subjected to cell fractionation studies. Compounds 14c and 14f were shown to cause a very large increase in free heme in the cell (>40 fg/cell, which corresponds to >50% of total cellular heme) at 2.5 times the corresponding IC50 of the compound (Figures 3a and S4.2a). Compound 14g also caused a large increase in free heme (>20 fg/cell, see Figure S4.2b), smaller than 14c and 14f, but larger than CQ.18 This study confirmed that these triarylimidazoles inhibit Hz formation, causing an increase in free heme in the malaria parasite in a dose-dependent manner that coincides with decreased parasite survival. This strongly suggests that inhibition of Hz formation is the mechanism of action of these compounds. By contrast, 14d, which exhibited parasite activity despite showing no βH inhibition activity, brought about no increase in free heme with decreasing parasite survival (Figure 3b). Thus, 14d appears to exhibit an entirely different mechanism of action. This is reinforced by flow cytometry data, which showed that parasite cells treated with 14d contained less DNA and were considerably smaller and less complex than those treated with 14c, 14f, and 14g (see Figure S4.2c–f). They also appeared to be pyknotic by light microscopy (see Figure S4.2 g). It is noteworthy that this compound is much more cytotoxic than the others, and this may be the basis of its parasite activity.

Figure 3.

Dose response curves for amount of free non-Hz heme (fg/cell) and the percent parasite survival for (a) 14f, showing a cross over near the IC50, and (b) 14d, showing no increase in free heme with parasite growth inhibition.

In this study, purchased or synthesized triarylimidazoles were evaluated for their ability to inhibit βH formation and prevent parasite growth. Furthermore, the RIs and SIs were assessed for selected analogues, which showed low CQ cross-resistance and high selectivity for P. falciparum over mammalian cells, supporting the Hz-inhibition pathway as an effective and unique drug target. Parasite activity relied on very specific substituents, showing that the scaffold was not amenable to structural changes on ring A. There did not appear to be a direct correlation between βH inhibition and parasite activity. This is not surprising given that access to the digestive vacuole, including pH trapping, is likely to play a crucial role in the relative potency of a compound’s ability to inhibit cellular hemozoin formation. Indeed, for this series there is clear evidence of hemozoin inhibition in the cell. For the three βH inhibitors selected for testing, intracellular free heme levels correlated with parasite growth inhibition. These derivatives are extraordinary probe molecules for investigating the properties and effects of free heme in the malaria parasite in view of the unusually high levels achieved. Investigations of the relationship between cellular accumulation, free heme levels and activity for this and other series are currently ongoing.19 Such data are crucial for gaining a detailed understanding of the mechanism of action of Hz inhibitors.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Rebecca D. Sandlin and David W. Wright from the Department of Chemistry, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, USA for collaboration on the HTS as well as Carmen de Kock from the Division of Pharmacology, Department of Medicine, University of Cape Town for providing cytotoxicity data.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS

- βH

β-hematin

- Hz

hemozoin

- LDH

lactate dehydrogenase

- CQ

chloroquine

- RI

resistance index

- SI

selectivity index

- CHO

Chinese hamster ovarian

- VU

Vanderbilt University

- UCT

University of Cape Town

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.6b00416.

Experimental methods including chemistry, detergent mediated assay for β-hematin inhibition, LDH malaria parasite survival assay, cell fractionation and cytotoxicity (PDF)

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written by K.J.W. with guidance and editing from T.J.E. and R.H. High throughput screening, scaffold analysis, synthesis, and SAR analysis was carried out by K.J.W. under the supervision of T.J.E. and R.H. Parasite assays and cell fractionation studies were conducted and analyzed by J.M.C. under the supervision of P.J.S. and T.J.E. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01AI110329. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Gamo F.-J.; Sanz L. M.; Vidal J.; de Cozar C.; Alvarez E.; Lavandera J.-L.; Vanderwall D. E.; Green D. V. S.; Kumar V.; Hasan S.; Brown J. R.; Peishoff C. E.; Cardon L. R.; Garcia-Bustos J. F. Thousands of Chemical Starting Points for Antimalarial Lead Identification. Nature 2010, 465, 305–312. 10.1038/nature09107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guiguemde W. A.; Shelat A. A.; Bouck D.; Duffy S.; Crowther G. J.; Davis P. H.; Smithson D. C.; Connelly M.; Clark J.; Zhu F.; Jimenez-Diaz M. B.; Martinez M. S.; Wilson E. B.; Tripathi A. K.; Gut J.; Sharlow E. R.; Bathurst I.; Mazouni F. E.; Fowble J. W.; Forquer I.; McGinley P. L.; Castro S.; Angulo-Barturen I.; Ferrer S.; Rosenthal P. J.; DeRisi J. L.; Sullivan D. J. Jr; Lazo J. S.; Roos D. S.; Riscoe M. K.; Phillips M. A.; Rathod P. K.; Van Voorhis W. C.; Avery V. M.; Guy R. K. Chemical Genetics of Plasmodium falciparum. Nature 2010, 465, 311–315. 10.1038/nature09099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Antimalarial Drug Resistance. http://www.who.int/malaria/areas/drug_resistance/overview/en/ (October 2014).

- Fidock D. A.; Nomura T.; Talley A. K.; Cooper R. A.; Dzekunov S. M.; Ferdig M. T.; Ursos L. M. B.; Sidhu A. S.; Naude B.; Deitsch K. W.; Su X.; Wootton J. C.; Roepe P. D.; Wellems T. E. Mutations in the P. falciparum Digestive Vacuole Transmembrane Protein PfCRT and Evidence for Their Role in Chloroquine Resistance. Mol. Cell 2000, 6, 861–871. 10.1016/S1097-2765(05)00077-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan T. J.; Ross D. C.; Adams P. A. Quinoline Anti-Malarial Drugs Inhibit Spontaneous Formation of β-Haematin (Malaria Pigment). FEBS Lett. 1994, 352, 54–57. 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00921-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohle D. S.; Helms J. B. Synthesis of β-Hematin by Dehydrohalogenation of Hemin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1993, 193, 504–508. 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorn A.; Stoffel R.; Matile H.; Bubendorf A.; Ridley R. Malarial Haemozoin/Beta-Haematin Supports Haem Polymerization in the Absence of Protein. Nature 1995, 374, 269–271. 10.1038/374269a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter M. D.; Phelan V. V.; Sandlin R. D.; Bachmann B. O.; Wright D. W. Lipophilic Mediated Assays for β-Hematin Inhibitors. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screening 2010, 3, 285–292. 10.2174/138620710790980496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan T. J.; Hempelmann E.; Mavuso W. W. Characterisation of Synthetic β-Haematin and Effects of the Antimalarial Drugs Quinidine, Halofantrine, Desbutylhalofantrine and Mefloquine on Its Formation. J. Inorg. Biochem. 1999, 73, 101–107. 10.1016/S0162-0134(98)10095-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan D. J.; Gluzman I. Y.; Russell D. G.; Goldberg D. E. On the Molecular Mechanism of Chloroquine’s Antimalarial Action. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1996, 93, 11865–11870. 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ncokazi K. K.; Egan T. J. A Colorimetric High-Throughput β-Hematin Inhibition Screening Assay for Use in the Search for Antimalarial Compounds. Anal. Biochem. 2005, 338, 306–319. 10.1016/j.ab.2004.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akoyunoglou J.-H. A.; Olcott H. S.; Brown W. D. Ferrihemochrome and Ferrohemochrome Formation with Amino Acids, Amino Acid Esters, Pyridine Derivatives, and Related Compounds. Biochemistry 1963, 2, 1033–1041. 10.1021/bi00905a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurosawa Y.; Satoh T.; Dorn A.; Matile H.; Kitsuji-Shirane M.; Hofheinz W.; Kansy M.; Ridley R. G. Haematin Polymerisation Assay as a High-Throughput Screen for Identification of New Antimalarial Pharmacophores. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2000, 44, 2638–2644. 10.1128/AAC.44.10.2638-2644.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush M. A.; Baniecki M. L.; Mazitschek R.; Cortese J. F.; Wiegand R.; Clardy J.; Wirth D. F. Colorimetric High-Throughput Screen for Detection of Heme Crystallization Inhibitors. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009, 53, 2564–2568. 10.1128/AAC.01466-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandlin R. D.; Carter M. D.; Lee P. J.; Auschwitz J. M.; Leed S. E.; Johnson J. D.; Wright D. W. Use of the NP-40 Detergent-Mediated Assay in Discovery of Inhibitors of β-Hematin Crystallization. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 3363–3369. 10.1128/AAC.00121-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandlin R. D.; Fong K. Y.; Wicht K. J.; Carrell H. M.; Egan T. J.; Wright D. W. Identification of beta-Hematin Inhibitors in a High-Throughput Screening Effort Reveals Scaffolds with in vitro Antimalarial Activity. Int. J. Parasitol.: Drugs Drug Resist. 2014, 4, 316–325. 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combrinck J. M.; Mabotha T. E.; Ncokazi K. K.; Ambele M. A.; Taylor D.; Smith P. J.; Hoppe H. C.; Egan T. J. Insights into the Role of Heme in the Mechanism of Action of Antimalarials. ACS Chem. Biol. 2013, 8, 133–137. 10.1021/cb300454t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combrinck J. M.; Fong K. Y.; Gibhard L.; Smith P. J.; Wright D. W.; Egan T. J. Optimization of a Multi-Well Colorimetric Assay to Determine Haem Species in Plasmodium falciparum in the Presence of Antimalarials. Malar. J. 2015, 14, 1–14. 10.1186/s12936-015-0729-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wicht K. J.; Combrinck J. M.; Smith P. J.; Hunter R.; Egan T. J. Identification and SAR Evaluation of Hemozoin-Inhibiting Benzamides Active against Plasmodium falciparum. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 6512–6530. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plouffe D.; Brinker A.; McNamara C.; Henson K.; Kato N.; Kuhen K.; Nagle A.; Adrian F.; Matzen J. T.; Anderson P.; Nam T.-g.; Gray N. S.; Chatterjee A.; Janes J.; Yan S. F.; Trager R.; Caldwell J. S.; Schultz P. G.; Zhou Y.; Winzeler E. A. In Silico Activity Profiling Reveals the Mechanism of Action of Antimalarials Discovered in a High-Throughput Screen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008, 105, 9059–9064. 10.1073/pnas.0802982105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong K. Y.; Sandlin R. D.; Wright D. W. Identification of β-Hematin Inhibitors in the MMV Malaria Box. Int. J. Parasitol.: Drugs Drug Resist. 2015, 5, 84–91. 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan L.; Wang X.; Wang S.; Li S.; Li Q.; Tian R.; Li M. Synthesis, Characterization, and Electrochemical Properties of Imidazole Derivatives Functionalized Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2008, 22, 331–336. 10.1002/poc.1481. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.