Abstract

Background

Prior research has shown that anxiety symptoms predict later depression symptoms following bereavement. Nevertheless, no research has investigated mechanisms of the temporal relationship between anxiety and later depressive symptoms or examined the impact of depressive symptoms on later anxiety symptoms following bereavement.

Methods

The current study examined perceived emotional social support as a possible mediator between anxiety and depressive symptoms in a bereaved sample of older adults (N = 250). Anxiety and depressive symptoms were measured at Wave 1 (immediately after bereavement), social support was measured at Wave 2 (18 months after bereavement), and anxiety and depressive symptoms were also measured at Wave 3 (48 months after bereavement).

Results

Using Bayesian structural equation models, when controlling for baseline depression, anxiety symptoms significantly positively predicted depressive symptoms 48 months later, Further, perceived emotional social support significantly mediated the relationship between anxiety symptoms and later depressive symptoms, such that anxiety symptoms significantly negatively predicted later emotional social support, and emotional social support significantly negatively predicted later depressive symptoms. Also, when controlling for baseline anxiety, depressive symptoms positively predicted anxiety symptoms 48 months later. However, low emotional social support failed to mediate this relationship.

Conclusions

Low perceived emotional social support may be a mechanism by which anxiety symptoms predict depressive symptoms 48 months later for bereaved individuals.

Bereavement and spousal loss is especially common in later life with 24.7% of adults ages 65 and older being widowed [1]. One study found that over a course of 2.5 years, 8.1% of older adults reported losing a spouse [2]. Bereavement also was associated with both anxiety [3–9] and depressive symptoms [7; 9–14]. Additionally in those experiencing bereavement, higher anxiety was associated with higher perceived loss of control [15], lower energy [16], increased suicidal ideation [17], increased risk of a heart attack [17], increased risk of stomach problems [17], poorer health [16], and greater difficulty sleeping [16] compared to those with lower anxiety. Similarly, in those experiencing bereavement, higher depression was associated with higher blood pressure [17], poorer health [17], greater cognitive impairment [18] and poorer coping [19] compared to those with lower depression. Given the wide-ranging influence of anxiety and depressive symptoms in those who have experienced loss, it is important to understand the longitudinal relationship between anxiety and depressive symptoms following bereavement as well as potential mediators of this relationship.

In evidence on the longitudinal relationship between anxiety and depression outside the context of bereavement, a meta-analysis examining 29 studies and over 20,000 people, showed that anxiety symptoms positively predicted later depressive symptoms with an estimated longitudinal association of r = 0.34 [20; 21]. Likewise, anxiety symptoms predicted depressive symptoms across many time scales, ranging from hours to years [22–28]. Similarly, in a meta-analysis of the broader literature including approximately 8,000 persons, depressive symptoms predicted later anxiety symptoms with an average longitudinal association of r = 0.35 [20; 29].

Nonetheless, literature on the longitudinal relationship between anxiety and depression in the context of bereavement is much more scarce. Following bereavement, two studies found that anxiety symptoms predicted later depressive symptoms [5; 16]. At the same time, the relationship between depression and later anxiety has not been examined within this context. Thus, despite robust bi-directional associations between anxiety and depression in younger populations, no studies have actually tested whether a bi-directional relationship exists between anxiety and depression in older adult populations. In addition, no prior research has examined the mechanism of this relationship in the context of bereavement or in an elderly population. Studying such mechanisms within older adults will become increasingly important as, by the year 2033, those who are 65-years and older will outnumber those 18 and younger in the United States [30].

There is reason to focus on perceived emotional social support as a possible mediator of this relationship. Following widowhood, the feeling of anxiety and dread about other bad things happening in the future is theorized to lead many either to emotionally and socially withdraw to conserve one’s energy for personal coping [31], or to engage in behaviors that might push others away. The impact of such withdrawal or negative behaviors may be greater in aging widows/widowers, as older adulthood (even outside the context of bereavement) is a time frequently associated with decreasing social support, due to increasing physical barriers and loss in one’s social circles [32]. Thus, bereavement in older adulthood is likely to be a time of considerable anxiety, dread, and tension, and these feelings are likely to lead to greater withdrawal, poor emotional disclosure, and unaffiliative behaviors.

A lack of emotional support following expressions of anxiety may be particularly impactful among older adults. Low social support in this population may contribute to feelings of loneliness, isolation [21; 33; 34], and emotional isolation [21]. By not having sufficient support and outlets to cope with and process the loss, social and emotional isolation may be a primary mechanism between bereavement anxiety and later depression [35]. In sum, high anxiety following widowhood is theorized to lead to friends’ departure, low emotional support, isolation, and ultimately depression.

Some evidence for this theory comes from nonbeareaved younger samples. Higher anxiety symptoms were associated with more difficulty in the social domain [including difficulty making friendships; 36; 37] and more difficulty with emotional self-disclosure [38; 39]. Chronic worrying also has been associated with impacting significant others in unaffiliative ways [40]. In longitudinal studies, anxiety symptoms unidirectionally predicted later low social support, and such lack of social support did not increase subsequent anxiety symptoms [41; 42]. In addition, lower levels of perceived emotional social support predicted higher depressive symptoms longitudinally [10; 12; 43; 44] following negative life events. There is also evidence that perceived emotional social support may be a mechanism by which anxiety leads to depression. One prior study found that perceptions of intimacy in close and group relationships mediated the longitudinal relationship between anxiety and later depressive symptoms [28]. In another study, interpersonal dysfunction mediated the relationship between generalized anxiety disorder and depressive symptoms [45].

Additional evidence comes from cross-sectional data using bereavement samples. For example, anxiety symptoms were associated with low emotional social support in persons who had experienced a stillbirth [which has been noted as a form of bereavement; 46; 47] and in bereaving spouses [48]. In addition, in observations of widows discussing their emotional reactions to the loss of their spouses, those perceived as less well-adjusted evoked greater frustration and less compassion from onlookers, compared to those who were perceived as better adjusted [49]. In turn, deficits in support networks, loneliness, and the amount of emotional support received from one’s friendships have also been cross-sectionally linked to depression in older adults experiencing bereavement [50; 51]. Further, among the elderly experiencing bereavement, a strong relationship has been found between lacking help in making decisions and feeling more blue or depressed [52]. Thus, persons experiencing and expressing their anxiety may elicit low compassion and a lack of emotional social support from others, leading to fewer social resources, lower emotional support, less helping making decisions and ultimately depression.

The goal of the current study was to examine perceived emotional social support as a mechanism of the relationship between post-bereavement earlier anxiety and later depressive symptoms utilizing a longitudinal design in an older adult sample. We also tested whether the relationship between anxiety and depression was unidirectional or bidirectional following bereavement in older adults. Face-to-face interviews were conducted 6-months (Wave 1), 18-months (Wave 2), and 48-months (Wave 3) after a spouse’s death. A body of literature regarding bereavement trajectories supports this timing of measurement points. The precedent in spousal bereavement literature is to assess symptoms post bereavement at 3–7 months, then between 12–18 months, and at multiple time points in years with a particular interest in the first five years after bereavement [53–60]. Some research shows that bereavement symptoms are still present decades after the loss [61]. The interviews consisted of a large set of questions including validated anxiety and depression scales. Social support was defined using two highly correlated items. Based on previous research, we hypothesized that: (1) anxiety symptoms (at Wave 1) would positively predict depressive symptoms (Wave 3) three and half years later while controlling for baseline depressive symptoms (Wave 1), (2) depressive symptoms (Wave 1) would positively predict anxiety symptoms (Wave 3) three and a half years later while controlling for baseline anxiety symptoms (Wave 1), (3) emotional social support (Wave 2) would mediate the relationship between anxiety symptoms (Wave 1) and later depressive symptoms (Wave 3), such that anxiety symptoms would negatively predict emotional social support, and emotional social support would negatively predict depressive symptoms, and (4) emotional social support (Wave 2) would not significantly mediate the relationship between depression (Wave 1) and later anxiety (Wave 3).

Method

Participants

Participants (N = 250) were collected through the Changing Lives of Older Couples (CLOC): A Study of Spousal Bereavement in the Detroit Area public use data set [62]. Data collection took place in three waves between 1987 and 1993. Individuals were identified through a two-stage area probability sample [62]. To be eligible for the study, participants needed to speak English, be at least 65 years old, and married at the time of initial contact. Following initial contact, death records of the state of Michigan were monitored, and participants were contacted 6-, 18-, and 48-months following the loss of their spouse [62]. Data were collected through interviews. Wave 1 interviews were conducted 6-months after the loss of a spouse (N = 250; 86% female, M age = 70.11, 84.4% Caucasian, 15.6% African American). Wave 2 interviews were conducted 18-months post-bereavement (N = 210), and the third and final wave of data was collected 48-months post-bereavement (N = 106).

Measures

Anxiety Subscale of the Symptom Checklist-90 Revised

Anxiety symptoms were measured during each wave with the 10-item anxiety subscale of the Symptom Checklist-90 Revised (SCL-90-R) [63], which is a self-report questionnaire designed to measure anxiety symptoms in the general population. See Table 1 for items. The 10-item anxiety subscale has high convergent validity with the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) anxiety subscale [64] and the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) [65]. Furthermore, high levels of invariance across gender have been noted [66], and high construct validity has been found as well [67]. In the current sample, the internal consistency of this subscale was high (α = .84) [62]. Responses were measured on a five point Likert scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely).

Table 1.

Anxiety, Depression, and Social Support Scales

| Measure | Item | Scale |

|---|---|---|

| SCL-90-R | [How much have you been bothered by] nervousness or shakiness? |

Not at all 1—5 extremely |

| …trembling? | Not at all 1—5 extremely | |

| …feeling suddenly scared for no reason? | Not at all 1—5 extremely | |

| …feeling fearful? | Not at all 1—5 extremely | |

| …heart pounding or racing? | Not at all 1—5 extremely | |

| …feeling tense and keyed up in the past seven days? |

Not at all 1—5 extremely | |

| …spells of terror or panic? | Not at all 1—5 extremely | |

| …feeling so restless you couldn’t sit still? | Not at all 1—5 extremely | |

| …feeling that something bad is going to happen to you? |

Not at all 1—5 extremely | |

| …thoughts and images of a frightening nature? | Not at all 1—5 extremely | |

| CES-D | I felt depressed. | Hardly ever 1—3 most of the time |

| I felt that everything I did was an effort. | Hardly ever 1—3 most of the time | |

| My sleep was restless. | Hardly ever 1—3 most of the time | |

| I was not happy. | Hardly ever 1—3 most of the time | |

| I felt lonely. | Hardly ever 1—3 most of the time | |

| People were unfriendly. | Hardly ever 1—3 most of the time | |

| I did not enjoy life. | Hardly ever 1—3 most of the time | |

| I did not feel like eating. My appetite was poor. | Hardly ever 1—3 most of the time | |

| I felt sad | Hardly ever 1—3 most of the time | |

| I felt that people disliked me. | Hardly ever 1—3 most of the time | |

| I could not get ‘going.’ | Hardly ever 1—3 most of the time | |

| Emotional Social Support |

On the whole, how much do your friends make you feel loved and cared for? |

A great deal 1—5 not at all |

| How much are your friends and relatives willing to listen when you need to talk about your worries or problems? |

A great deal 1—5 not at all |

Note: This table represents the items from the Symptoms Checklist 90-Revised, the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale, and the constructed Social Support Scale.

Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale

The CES-D, a self-report questionnaire meant to evaluate depressive symptoms in the general population [68], was delivered during all 3 waves. The original scale had 20-items, however, an 11-item version was used here. See Table 1 for items. The 11-item version was deemed preferable for this study because the full scale was found to be taxing for older adults [69]. Responses were measured on a three point Likert scale from 1 (hardly ever) to 3 (most of the time). The 20-item scale showed good convergent validity when compared to the SCL-90-R depression scale (r = .73-.89) [70], the BDI, and the MMPI-II [71]. The 11-item subscale also has been found to have good construct validity [72]. In the current sample, internal consistency of this scale was high (α = .84) [62].

Nevertheless, the 11-item CES-D contains questions that are not specific to depressive symptoms. For example, it also measures social relationships (i.e. people being unfriendly, people disliking them, and loneliness) and symptoms that overlap with anxiety (i.e. restlessness, appetite disturbance). To ensure that these items did not undermine the theoretical constructs, they were removed for the primary analyses (note that additional analyses were also conducted with the original 11-item CES-D; see planned analyses below). The remaining 6-item version still had high internal consistency (α = 0.80).

Perceived Emotional Social Support Scale

Two items were used to measure perceived emotional social support: (1) “On the whole, how much do your friends make you feel loved and cared for?” and (2) “How much are your friends and relatives willing to listen when you need to talk about your worries or problems?” This scale was given during Wave 2, 18-months after the loss of a spouse. Internal consistency of this scale was high (α = .80) [62]. Responses were measured on a five point Likert scale from 1 (a great deal) to 5 (not at all). Items were then reverse coded, such that higher scores indicated higher levels of social support.

Although this scale was developed for this study specifically, it shares a great deal of overlap between previously validated scales. In particular, it is similar to (1) The Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) Social Support [which likewise assesses social support using items such as “love and affection”, “listen to you”, “confide in”, and “share worries with”; 73]; (2) The Duke-UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire [also using the following similar items “Chances to talk with someone about [all types] of problems” and “Love and affection”; 74], and (3) the Interview Schedule for Social Interaction [similarly to the current study it asks “Do you have someone you can share your most private feelings with (confide in) or not?” as well as multiple items assessing the perceived love and care; 75; 76]. Thus, although we used a novel two-item scale, it contained high item content validity with previously validated scales.

Covariates

Note that the analyses were repeated with and without controlling for the following sources of stress. During the second wave, persons were asked if they (1) experienced a life-threatening illness or injury, (2) have a serious but not life-threatening illness, (3) were robbed or burglarized, (4) involuntarily lost a job for reasons other than retirement, (5) have serious financial problems or difficulties, and (6) moved to a new residence.

Planned Analyses

All primary analyses used Bayesian structural equation models (BSEM) in Mplus 7. BSEM has unique advantages over frequentist SEM: (1) unlike frequentist SEM, which usually requires considerably larger sample sizes, BSEM coverage rates have been shown to perform well in simulation studies with sample sizes ranging from 25 to 1000 [77; 78], (2) BSEM does not have problems with non-convergence, nonsensical values, and Heywood cases [79; 80], and (3) BSEM tends to perform well under conditions of multicollinearity [81; 82]. Notably, BSEM also handles ordinal data well, allowing distributions to be directly set within the modeling framework [83]. Missing data was handled through random forest multiple imputation using the missForest package, which has greater accuracy than other multiple imputation methods [84].

Prior to the primary analyses, to ensure that there were not baseline differences between completers and non-completers, a Bayesian independent samples t-test was conducted on the factor scores of the anxiety and depression variables at Wave 1 using JASP [85]. Note that the test statistic in a Bayesian t-test is the Bayes factor. A Bayes factor is a model-based estimate of the odds of the alternative hypothesis being true compared to the null hypothesis. A Bayes Factor ranges from 0 to infinity, and the higher the Bayes factor the more evidence there is to reject the null hypothesis (i.e. that there are no differences between completers and non-completers). Values less than 1 suggest that there is more support for the null-hypothesis than there is for the alternative hypothesis [86]. Note that the default non-informative Cauchy prior was used [85].

First, we tested the first and second hypotheses that anxiety symptoms at Wave 1 would predict depressive symptoms at Wave 3, controlling for Wave 1 anxiety symptoms, and depressive symptoms at Wave 1 would predict anxiety symptoms at Wave 3, controlling for Wave 1 depression symptoms. Item residuals between Wave 1 and Wave 3 were allowed to covary. Next, we tested the hypothesis that the relationship between anxiety symptoms at Wave 1 and depressive symptoms at Wave 3 would be mediated by perceived emotional social support, controlling for Wave 1 depression symptoms (we also tested social support mediating the relationship between depression and later anxiety, controlling for earlier anxiety). Mediation was estimated directly using indirect and total effect model parameters, and these parameters were estimated directly using the Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) estimates. As with other mediation approaches (i.e. bootstrapping), BSEM parameter estimates do not make any distributional assumptions of the parameters in the estimation [77].

Model fit was assessed based on the posterior predictive p-value (PPP) [87; 88], which uses the likelihood-ratio chi-square test of the estimated data against the observed data. Based on simulation work, PPP values above 0.050 represent good model fit [83; 87]. Instead of p-values, which have been shown to be highly unreliable [89], BSEM uses Bayesian credible intervals wherein the model suggests that the true parameter has a 95% chance of falling within the specified credible interval bounds [90] and is determined to be significant if credible intervals do not contain 0. Non-informative priors were used in the modeling approach as recommended by Asparouhov and Muthen [83] and Muthén and Asparouhov [87]. All regression coefficients are also presented with a Cohen’s d effect size based on the following formula, [91], and consequently the magnitude of the effect size suggests that 0.2 represents a small effect, 0.5 represents a medium effect, and over 0.8 represents a large effect [92].

All primary analyses were conducted using the CES-D items that did not overlap with emotional social relationships or with anxiety (see CES-D section above). However, to be comprehensive, all analyses were repeated with the 11-item CES-D scale. Further, to ensure that the results were not driven by experiencing other sources of stress, all analyses were repeated using each stress variable as a covariate in predicting anxiety and depression at wave 3. Note that both sets of results are reported in footnotes below.

Results

Differences between Completers and Non-Completers

For baseline anxiety, the results suggested that it was unlikely that there was a difference (BF = 0.764) between completers (M = 12.370, SD = 3.070) and non-completers (M = 13.380, SD = 4.647). Likewise, for depression the results suggested that it was unlikely that there was a difference (BF = 0.144) between completers (M = 11.04, SD = 1.707) and non-completers (M = 11.00, SD = 1.707).

Hypotheses 1-2: Anxiety Predicts Later Depression and Depression Predicts Later Anxiety

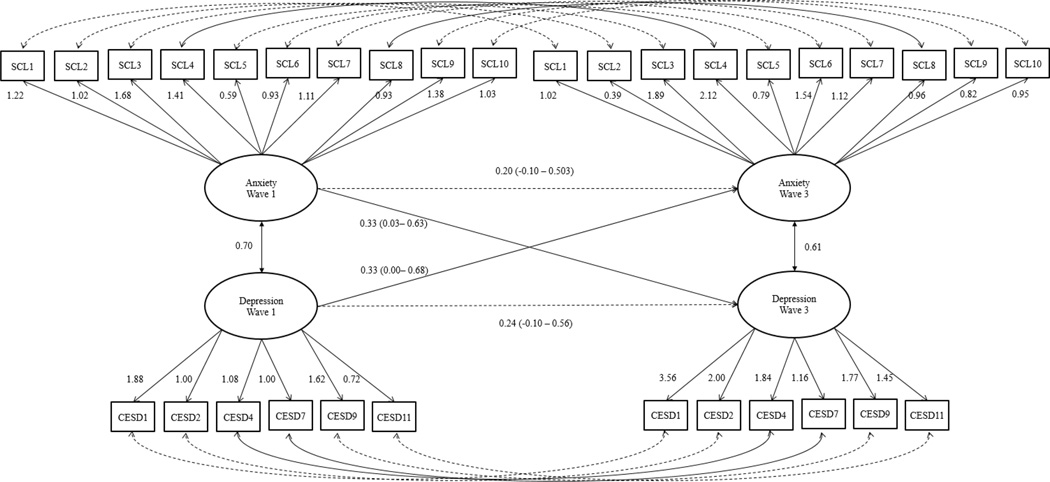

The first analysis examined our first and second hypotheses. The model demonstrated good fit (PPP = .100). Supporting our first hypothesis, anxiety symptoms significantly positively predicted subsequent depressive symptoms when controlling for baseline depression symptoms (B = 0.331, CI = 0.004 - 0.682, d= 0.271; see Figure 1).2,3 Likewise, supporting our second hypothesis, depressive symptoms significantly predicted later anxiety symptoms when controlling for baseline depression symptoms (B = 0.330, CI = 0.027 - 0.632, d = 0.301).

Figure 1.

In this figure depicts the first model results where anxiety and depressive symptoms at wave 1 predict anxiety and depressive symptoms at wave 3. Solid lines represent significant connections, whereas dotted lines represent insignificant connections.

Hypotheses 3-4: Emotional Social Support as a Mediator

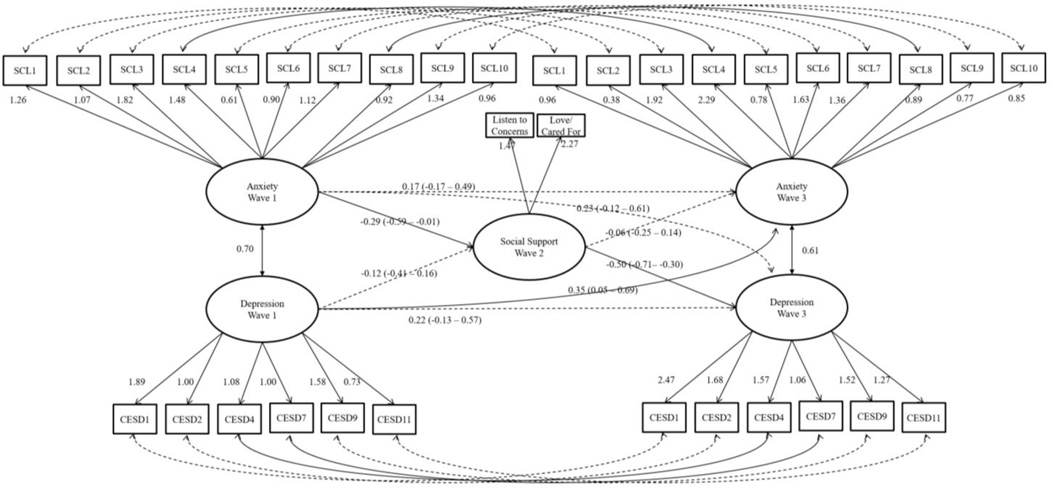

The next set of analyses examined our third and fourth hypotheses. The model demonstrated good fit (PPP = .058). The total effect of anxiety at Wave 1 on depression at Wave 3 was significant (B = 0.368, CI = 0.009 - 0.774, d = 0.274), suggesting that anxiety continued to predict later depression when emotional social support was included in the model. Supporting our third hypothesis, anxiety symptoms significantly (B = -0.288, CI = -0.587— -0.005, d = -0.275) negatively predicted later emotional social support, and social support significantly (B = -0.496, CI = -0.711— -0.297, d= -0.662) negatively predicted later depressive symptoms (see Figure 2). Further, the indirect effect of anxiety on depression through emotional social support was significantly positive (B = 0.138, CI = 0.003 - 0.308, d = 0.253), suggesting that perceived emotional social support significantly mediated the relationship between anxiety symptoms and later depressive symptoms. Additionally, the direct relationship between anxiety symptoms and later depressive symptoms was no longer significant (B = 0.227, CI = -0.122—0.609, d = 0.176). Based on the indirect and total effect estimates, emotional social support mediated 38% of the total variance in anxiety predicting later depression. These results suggest that low emotional social support mediates a substantial portion of the variation between early anxiety and later depression.

Figure 2.

In this figure depicts the second model results where social support mediates at wave 2 the relationship between anxiety at wave anxiety and depressive symptoms at wave 3. Solid lines represent significant connections, whereas dotted lines represent insignificant connections.

Supporting our fourth hypothesis, in contrast to social support significantly mediating the relationship between anxiety and later depression, the relationship between earlier depression and later social support was not significant (B = -0.118, CI = -0.405 – 0.158, d = -0.143), and likewise, social support did not significantly predict later anxiety (B = -0.055, CI = -0.247 – 0.137, d = -0.080). Although the total effect of depression on later anxiety remained significant with social support in the model (B = 0.356, CI = 0.057 - 0.698, d = 0.311), the indirect effect of depression on later anxiety mediated by social support was not significant (B = 0.003, CI = - 0.003 – 0.051, d = 0.022). Thus, social support uniquely mediated the relationship between anxiety and later depression, and not vice versa.4,5

Discussion

Supporting prior research using bereaved samples [5; 16] and the wider literature of anxiety and later depressive symptoms [20; 22–26; 28], the current results indicated that higher anxiety symptoms predicted higher depressive symptoms 48-months post bereavement. Additionally, depression following bereavement predicted anxiety symptoms 48-months later, suggesting a bi-directional relationship between anxiety and depressive symptoms post-bereavement. Furthermore, higher anxiety symptoms predicted lower emotional social support and lower emotional support predicted higher depressive symptoms. Thirty-eight percent of the relationship between earlier anxiety symptoms and later depressive symptoms was explained by the latter analysis. Nonetheless, perceived emotional social support failed to mediate the relationship between depression and later anxiety.

Findings in this age group may be particularly noteworthy given the unique developmental contexts of older adulthood. Older adults are more likely to experience declining physical health [93], bereavement [94], greater social isolation [95], and a loss of social support [96]. During such a pivotal time, anxious reactions to spousal loss are common [3–9], as the loss of one’s spouse often signifies the beginning of feeling socially isolated [32; 97]. Supporting prior theories that anxiety reactions to bereavement in older adulthood lead to social withdrawal to conserve one’s energy for personal coping [31], and contextualizing findings that less well-adjusted reactions to grief evoke frustration and low compassion from others [49], the current findings suggest that anxiety following bereavement substantially contributes to one’s level of social support during this pivotal time. Paired with findings that some older adults attempt to avoid anything that reminds them of their spouse in order to cope with spousal loss [98], future research should examine social avoidance, withdrawal, and interpersonal rejections as potential mechanisms between anxiety and low emotional social support following spousal loss in older adults.

Building on the broad literature supporting the importance of social support following bereavement and in older adulthood [10; 99], the current research also found that low emotional social support predicted symptoms of high depression two and a half years later. It is possible that the relationship between social support and later depression in bereaving older adults occurs due to those with low social support having insufficient social outlets to cope and process the loss of their spouse, and lead to feelings of loneliness, isolation [21; 33; 34], and emotional isolation [21]. Thus, future research should examine loneliness, and emotional isolation as potential pathways between low social support and later depressive symptoms in widows.

The present findings also relate to coping with stressful life events. According to theory, critical life events require major readjustment. Intensity of stress depends on whether the demands of a situation exceed individuals’ emotional coping resources [100]. Additionally, according to Holmes and Rahe [101], the death of a spouse is the most stressful life change event because it requires the most adaptive coping behaviors and is accompanied by the most psychological distress. One study found that 14-months after spousal bereavement, about a third of bereaved individuals had difficulties developing new intimate relationships, and the problem was particularly salient among older adults [102]. A similar study found that 25 months later, 37% of widowers and 58% of widows reported difficulties developing new relationships [103]. Furthermore, number of family and friends in the social network and visits from family members tend to decline over the first year and half of bereavement [57]. Our findings add to prior findings suggesting that higher anxiety may be related to such social support decline [104].

Our results support prior findings that elevated anxiety [3–9] and depressive symptoms [7; 9–14] may hold particular importance following a loss, especially in regard to the social adjustment of the widow or widower. Additionally, social support may act as a protective factor against potentially adverse effects of stressful life events, as has been found previously; specifically, high levels of social support were associated with low depressive symptoms [10; 12; 43; 44]. Therefore, social support is particularly important for protecting against psychological distress following what is considered the most stressful life event, spousal bereavement. Prior studies also found that bereavement increased the need for social support [105]. Additionally, those who had lost a spouse but perceived that they were more socially supported were less distressed than those who felt less socially supported [106–108]. These results may suggest that interventions for bereaved older adults should include a component targeted toward reducing anxiety symptoms and fostering approach strategies, rather than avoidance strategies. They also suggest that targeting social support may be helpful to bereaved individuals, especially those exhibiting anxiety symptoms. In addition, because we found this relationship within the first 4 years’ post-bereavement, it is possible that anxiety may rapidly progress toward later depressive symptoms. Thus, intervention programs may be especially important during the first four years after loss of a spouse for older adults.

These results are consistent with and incrementally extend prior findings, as well as corroborate literature showing that anxiety and depressive symptoms bi-directionally predict one another years later [20; 21]. This is the first time a temporal mechanism between anxiety and depression has been examined in an older adult sample; all prior studies used adolescent or young adult samples. Nevertheless, in younger populations outside the context of bereavement, prior research found four constructs that partially longitudinally mediated the relationship between anxiety and depressive symptoms: avoidance, sociability, interpersonal oversensitivity, and perceptions of close and group relationships [26; 28; 45]. The present findings add poor interpersonal relationships to this list, suggesting that perceived emotional support may be a mechanism by which anxiety predicts later depression. Furthermore, in pairing prior literature with the current results, the depth of one’s social connections may be as influential as breadth in mediating the relationship between anxiety and later depression.

Although this study makes important contributions to the bereavement literature as well as the broader anxiety and depression literature, it is not without limitations. Additionally, the current research only utilized self-report measures, and, consequently, the results could be impacted by potential response biases. Consequently, the results should be replicated using multi-trait multimethod research with multiple informants. In particular, although we found a bi-directional longitudinal relationship between anxiety and depression following bereavement, we only found that social support unidirectionally mediated anxiety and later depression. Although little is known about the relationship between depression and later anxiety, future research should examine behavioral activation and avoidance as potential meditational candidates. In particular, depression was associated with low behavioral activation [109]. Decreases in behavioral activation could thereby decrease exposure to novel situations and experiences [109] and further exacerbate fear and avoidance cycles [109].

The current study sample also was not diverse, consisting primarily of heterosexual Caucasian females. Although a prior meta-analysis found that the relationship between anxiety and depressive symptoms was robust across gender and ethnicity [20], more research is needed to determine whether the mediating role of social support applies across different gender identities, sexual orientations, and ethnicities. We were also unable to control for other third-variables that could have connections with the constructs examined here (i.e. avoidance, neuroticism, coping techniques, religiosity), and, consequently, future work should examine perceived emotional social support while also examining other potentially related control variables. Further, the current study used an emotional social support measure that has not been used in prior work, and, consequently, future work should attempt to replicate our findings with a validated measure. Moreover, although the study established emotional social support as mediating a large portion of the variance between anxiety and later depressive symptoms following bereavement, the current study could not establish mechanisms between anxiety and social support or between social support and depression. Likewise, although mediation provides a framework to examine mechanisms between processes, it should be noted that this does not imply that the statistical findings represent causal relationships, but rather a pattern of longitudinal findings that are indicative of risk factors. Notably, although the current use of structural equation modeling allows one to account for item-level measurement error from the examination of the relationship between constructs, it sacrifices the uniqueness of the importance of some items in favor of the shared covariance. Thus, future research should examine potential mediators between anxiety symptoms and social support, such as avoidance, and social support and depressive symptoms, such as loneliness.

Table 2.

Scale Correlations and Descriptive Statistics

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Anxiety Wave 1 | 1 | ||||

| 2. Depression Wave 1 | 0.40 | 1 | |||

| 3. Emotional Social Support Wave 2 | 0.29 | 0.08 | 1 | ||

| 4. Anxiety Wave 3 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.10 | 1 | |

| 5. Depression Wave 3 | 0.35 | 0.33 | 0.23 | 0.38 | 1 |

| M | 12.99 | 11.04 | 3.74 | 11.16 | 10.44 |

| SD | 4.11 | 1.62 | 1.83 | 2.41 | 1.15 |

| Range | 10–31 | 6–17 | 2–10 | 10–27 | 6–15 |

Note: This table first presents correlations between items in the first five rows of the table. Following this, the mean, standard deviation, and range of each of the scale measures.

Highlights.

Anxiety immediately following bereavement predicts depression four years later.

Depression immediately following bereavement predicts anxiety four years later.

Social support mediates the relationship between anxiety and depression

Acknowledgments

The availability of these data is made possible by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (Randolph M. Nesse, Principal Investigator, AG15948-01). The original data collection for the CLOC study was supported by NIA grants (Camille B. Wortman, Principal Investigator, AG610757-01, and James S. House, Principal Investigator, AG05561-01).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Note that the model including the 11-item CES-D also had good fit (PPP = .058). Also, the pattern of anxiety predicting depression was consistent with the primary findings, as anxiety also significantly (B = 0.387, CI = 0.079 - 0.737, d = 0.330) positively predicted later depression in using the 11-item CES-D. Likewise, the results also showed that the model using the 11-item CES-D was consistent in that depression at wave 1 significantly predicted anxiety at wave 3 (B = 0.468, CI = 0.154 - 0.873, d = 0.361).

Note that the model including the stress covariates also had good fit (PPP = .058). Also, the pattern of anxiety predicting depression was consistent with the primary findings, as anxiety also significantly (B = 0.410, CI = 0.807 - 0.387, d = 0.290) positively predicted later depression while controlling for later stress. Likewise, the results also showed that the model using the stress covariates was consistent in that depression at wave 1 significantly predicted anxiety at wave 3 (B = 0.444, CI = 0.115 - 0.780, d = 0.361).

Note that the model including the 11-item CES-D had good fit (PPP = .058). The pattern of emotional social support mediating the relationship between anxiety and depression held, as anxiety significantly negatively predicted emotional social support (B = -0.291, CI = -0.586— -0.012, d = -0.282) and emotional social support significantly negatively predicted depression (B = -0.306, CI = -0.502— - 0.123, d = -0.446). Further the indirect effect of anxiety on depression, mediated by emotional social support, was also significantly positive (B = 0.083, CI = 0.003—0.208, d = 0.221). Additionally, the direct effect of anxiety on later depression was no longer significant (B = 0.282, CI = -0.032—0.622, d = 0.237). Also like the 6-item CES-D results, the results suggested that baseline depression did not significantly predict social support (B = -0.119, CI = -0.390 - 0.149, d = -0.123), and social support did not significantly predict later anxiety (B = -0.017, CI = -0.220 – 0.175, d = -0.024). The total effect of depression on anxiety (B = 0.554, CI = 0.256 - 0.895, d = 0.480) remained significant, but the indirect effect of depression on later anxiety mediated by social support (B = 0.000, CI = -0.038 – 0.041, d = 0.000) was not significant for the 11-item CES-D. Consequently, the theoretical implications of the model, including the reduced CES-D compared to the 11-item CES-D, are the same.

Note that the model including the stress covariates also had good fit (PPP = .058). Likewise, the pattern of emotional social support mediating the relationship between anxiety and depression held, as anxiety significantly negatively predicted emotional social support (B = -0.333, CI = -0.665— -0.050, d = -0.316) and emotional social support significantly negatively predicted depression (B = -0.633, CI = -0.872— - 0.442 3, d = -0.799). Further the indirect effect of anxiety on depression, mediated by emotional social support, was also significantly positive (B = 0.211, CI = 0.024—0.426, d = 0.301). Additionally, the direct effect of anxiety on later depression was no longer significant (B = 0.184, CI = -0.192—0.554, d = 0.140). Likewise when controlling for stress covariates, the results suggested that baseline depression did not significantly predict social support (B = -0.129, CI = -0.450 - 0.176, d = - 0.121), and social support did not significantly predict later anxiety (B = -0.184, CI = -0.390 – 0.024, d = -0.248). The total effect of depression on anxiety (B = 0.367, CI = 0.080 - 0.633, d = 0.358) remained significant, but the indirect effect of depression on later anxiety mediated by social support (B = 0.016, CI = -0.031 – 0.101, d = 0.067) was not significant when controlling for stress covariates. Consequently, the theoretical implications of the model, including the stress covariates, are the same.

References

- 1.United States Census Bureau. America’s Families and Living Arrangements: 2015: Adults. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams BR, Sawyer Baker P, Allman RM, Roseman JM. Bereavement among African American and White older adults. J Aging Health. 2007;19(2):313–333. doi: 10.1177/0898264307299301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maccallum F, Sawday S, Rinck M, Bryant RA. The push and pull of grief: Approach and avoidance in bereavement. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2015;48:105–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2015.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meier AM, Carr DR, Currier JM, Neimeyer RA. Attachment anxiety and avoidance in coping with bereavement: Two studies. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2013;32(3):315–334. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prigerson HG, Shear MK, Newsom JT, et al. Anxiety among widowed elders: Is it distinct from depression and grief? Anxiety. 1996;2(1):1–12. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-7154(1996)2:1<1::AID-ANXI1>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Byrne GJ, Raphael B. The psychological symptoms of conjugal bereavement in elderly men over the first 13 months. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1997;12(2):241–251. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1166(199702)12:2<241::aid-gps590>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kreicbergs U, Valdimarsdottir U, Onelov E, et al. Anxiety and depression in parents 4–9 years after the loss of a child owing to a malignancy: A population-based follow-up. Psychol Med. 2004;34(8):1431–1441. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704002740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valdimarsdottir U, Helgason AR, Furst CJ, et al. Awareness of husband's impending death from cancer and long-term anxiety in widowhood: A nationwide follow-up. Palliat Med. 2004;18(5):432–443. doi: 10.1191/0269216304pm891oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitchell AM, Sakraida TJ, Kim Y, et al. Depression, anxiety and quality of life in suicide survivors: A comparison of close and distant relationships. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2009;23(1):2–10. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2008.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stroebe W, Zech E, Stroebe MS, Abakoumkin G. Does social support help in bereavement? Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2005;24(7):1030–1050. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murphy SA. Mental distress and recovery in a high-risk bereavement sample three years after untimely death. Nurs Res. 1988;37(1):30–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stroebe W, Stroebe M, Abakoumkin G, Schut H. The role of loneliness and social support in adjustment to loss: A test of attachment versus stress theory. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1996;70(6):1241–1249. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.6.1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jozwiak N, Preville M, Vasiliadis HM. Bereavement-related depression in the older adult population: A distinct disorder? J Affect Disord. 2013;151(3):1083–1089. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghesquiere A, Shear MK, Duan N. Outcomes of bereavement care among widowed older adults with complicated grief and depression. J Prim Care Community Health. 2013;4(4):256–264. doi: 10.1177/2150131913481231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ong AD, Bergeman CS, Bisconti TL. Unique effects of daily perceived control on anxiety symptomatology during conjugal bereavement. Personality and Individual Differences. 2005;38(5):1057–1067. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boelen PA, Prigerson HG. The influence of symptoms of prolonged grief disorder, depression, and anxiety on quality of life among bereaved adults. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2007;257(8):444–452. doi: 10.1007/s00406-007-0744-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen JH, Bierhals AJ, Prigerson HG, et al. Gender differences in the effects of bereavement-related psychological distress in health outcomes. Psychol Med. 1999;29(2):367–380. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798008137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ward L, Mathias JL, Hitchings SE. Relationships between bereavement and cognitive functioning in older adults. Gerontology. 2007;53(6):362–372. doi: 10.1159/000104787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bennett KM, Smith PT, Hughes GM. Coping, depressive feelings and gender differences in late life widowhood. Aging Ment Health. 2005;9(4):348–353. doi: 10.1080/13607860500089609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacobson NC, Newman MG. Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies National Harbor, MD; 2012. National Harbor, Maryland: 2012. Nov, The temporal relationship between anxiety and depression: A meta-analysis; p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Baarsen B. Theories on coping with loss: The impact of social support and self-esteem on adjustment to emotional and social loneliness following a partner's death in later life. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2002;57(1):S33–S42. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.1.s33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacobson NC, Newman MG. Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies. National Harbor, MD; 2012. National Harbor, Maryland: 2012. Nov, Anxiety as a temporal predictor of depression during brief time periods: An ecological momentary assessment; p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Starr LR, Davila J. Temporal patterns of anxious and depressed mood in generalized anxiety disorder: A daily diary study. Behav Res Ther. 2012;50(2):131–141. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Starr LR, Davila J. Cognitive and interpersonal moderators of daily co-occurrence of anxious and depressed moods in generalized anxiety disorder. Cognit Ther Res. 2012;36(6):655–669. doi: 10.1007/s10608-011-9434-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Swendsen JD. Anxiety, depression, and their comorbidity: An experience sampling test of the helplessness-hopelessness theory. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1997;21(1):97–114. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacobson NC, Newman MG. Avoidance mediates the relationship between anxiety and depression over a decade later. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2014;28(5):437–445. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Starr LR, Stroud CB, Li YI. Predicting the transition from anxiety to depressive symptoms in early adolescence: Negative anxiety response style as a moderator of sequential comorbidity. J Affect Disord. 2016;190:757–763. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.10.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jacobson NC, Newman MG. Perceptions of close and group relationships mediate the relationship between anxiety and depression over a decade later. Depression and Anxiety. 2016;33(1):66–74. doi: 10.1002/da.22402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jacobson NC, Newman MG. Anxiety and depression as bidirectional risk factors for one another: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. 2016 doi: 10.1037/bul0000111. Under Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Colby SLO. Current Population Reports. Washington DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2015. J. M. Projections of the size and composition of the U.S. population: 2014 to 2060. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hogan N, Morse JM, Tasón MC. Toward an experiential theory of bereavement. OMEGA: Journal of Death and Dying. 1996;33(1):43–65. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mullins LC, Dugan E. The influence of depression, and family and friendship relations, on residents' loneliness in congregate housing. Gerontologist. 1990;30(3):377–384. doi: 10.1093/geront/30.3.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Golden J, Conroy RM, Bruce I, et al. Loneliness, social support networks, mood and wellbeing in community-dwelling elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24(7):694–700. doi: 10.1002/gps.2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Baarsen B, Smit JH, Snijders TAB, Knipscheer KPM. Do personal conditions and circumstances surrounding partner loss explain loneliness in newly bereaved older adults? Ageing and Society. 1999;19(4):441–469. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cornwell EY, Waite LJ. Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and health among older adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2009;50(1):31–48. doi: 10.1177/002214650905000103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Langston CA, Cantor N. Social anxiety and social constraint: When making friends is hard. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;56(4):649–661. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scharfstein L, Alfano C, Beidel D, Wong N. Children with generalized anxiety disorder do not have peer problems, just fewer friends. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2011;42(6):712–723. doi: 10.1007/s10578-011-0245-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kahn JH, Garrison AM. Emotional self-disclosure and emotional avoidance: Relations with symptoms of depression and anxiety. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2009;56(4):573–584. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Post AL, Wittmaier BC, Radin ME. Self-disclosure as a function of state and trait anxiety. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1978;46(1):12–19. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.46.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Erickson TM, Newman MG, Siebert EC, et al. Does worrying mean caring too much? Interpersonal prototypicality of dimensional worry controlling for social anxiety and depressive symptoms. Behavior Therapy. 2016;47(1):14–28. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2015.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Friedmann E, Son H, Thomas SA, et al. Poor social support is associated with increases in depression but not anxiety over 2 years in heart failure outpatients. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2014;29(1):20–28. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0b013e318276fa07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paterson C, Robertson A, Nabi G. Exploring prostate cancer survivors' self-management behaviours and examining the mechanism effect that links coping and social support to health-related quality of life, anxiety and depression: A prospective longitudinal study. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2015;19(2):120–128. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2014.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aneshensel CS, Frerichs RR. Stress, support, and depression: A longitudinal causal model. Journal of Community Psychology. 1982;10(4):363–376. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cohen S, Hoberman HM. Positive events and social supports as buffers of life change stress. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1983;13(2):99–125. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Starr LR, Hammen C, Connolly NP, Brennan PA. Does relational dysfunction mediate the association between anxiety disorders and later depression? Testing an interpersonal model of comorbidity. Depress Anxiety. 2014;31(1):77–86. doi: 10.1002/da.22172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cacciatore J, Schnebly S, Froen JF. The effects of social support on maternal anxiety and depression after stillbirth. Health Soc Care Community. 2009;17(2):167–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2008.00814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Condon JT. Management of established pathological grief reaction after stillbirth. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1986;143(8):987–992. doi: 10.1176/ajp.143.8.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bergman EJ, Haley WE, Small BJ. The role of grief, anxiety, and depressive symptoms in the use of bereavement services. Death Studies. 2010;34(5):441–458. doi: 10.1080/07481181003697746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Keltner D, Bonanno GA. A study of laughter and dissociation: distinct correlates of laughter and smiling during bereavement. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1997;73(4):687–702. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.73.4.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Prince MJ, Harwood RH, Blizard RA, et al. Social support deficits, loneliness and life events as risk factors for depression in old age. The Gospel Oak Project VI. Psychol Med. 1997;27(2):323–332. doi: 10.1017/s0033291796004485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.van Grootheest DS, Beekman AT, Broese van Groenou MI, Deeg DJ. Sex differences in depression after widowhood. Do men suffer more? Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1999;34(7):391–398. doi: 10.1007/s001270050160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Balaswamy S, Richardson V, Price CA. Investigating patterns of social support use by widowers during bereavement. The Journal of Men's Studies. 2004;13(1):67–84. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Utz RL, Caserta M, Lund D. Grief, depressive symptoms, and physical health among recently bereaved spouses. Gerontologist. 2011;52(4):460–471. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnr110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bonanno GA, Mihalecz MC, LeJeune JT. The core emotion themes of conjugal loss. Motivation and Emotion. 1999;23(3):175–201. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Middleton W, Burnett P, Raphael B, Martinek N. The bereavement response: A cluster analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 1996;169(2):167–171. doi: 10.1192/bjp.169.2.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Field NP, Gal-Oz E, Bonanno GA. Continuing bonds and adjustment at 5 years after the death of a spouse. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71(1):110–117. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.71.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Utz RL, Swenson KL, Caserta M, et al. Feeling lonely versus being alone: loneliness and social support among recently bereaved persons. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2014;69B(1):85–94. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbt075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sasson I, Umberson DJ. Widowhood and depression: New light on gender differences, selection, and psychological adjustment. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2014;69B(1):135–145. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbt058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Galatzer-Levy IR, Bonanno GA. Beyond normality in the study of bereavement: heterogeneity in depression outcomes following loss in older adults. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(12):1987–1994. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Holland JM, Thompson KL, Rozalski V, Lichtenthal WG. Bereavement-related regret trajectories among widowed older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2014;69(1):40–47. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbt050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Carnelley KB, Wortman CB, Bolger N, Burke CT. The time course of grief reactions to spousal loss: evidence from a national probability sample. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2006;91(3):476–492. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.3.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nesse RM, Wortman C, House J, et al. Changing lives of older couples (CLOC): A study of spousal bereavement in the Detroit area, 1987–1993. Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 63.Derogatis LR. SCL-90: Administration, scoring and procedures manual-I for the revised version and other instruments of the psychopathology rating scale series. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Clinical Psychometrics Research Unit; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Derogatis LR, Rickels K, Rock AF. The SCL-90 and the MMPI: A step in the validation of a new self-report scale. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1976;128(280):280–289. doi: 10.1192/bjp.128.3.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Steer RA, Ranieri WF, Beck AT, Clark DA. Further evidence for the validity of the Beck Anxiety Inventory with psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1993;7(3):195–205. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Derogatis LR, Cleary PA. Factorial invariance across gender for the primary symptom dimensions of the SCL-90. British Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology. 1977;16(4):347–356. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1977.tb00241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Derogatis LR, Cleary PA. Confirmation of the dimensional structure of the SCL-90: A study in construct validation. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1977;33(4):981–989. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kohout F. The pragmatics of survey field work among the elderly. In: Wallace R, Woolson R, editors. The epidemiological study of the elderly. New York: Oxford University Press; 1992. pp. 99–119. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Weissman MM, Sholomskas D, Pottenger M, et al. Assessing depressive symptoms in five psychiatric populations: A validation study. Am J Epidemiol. 1977;106(3):203–214. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bush BA, Novack TA, Schneider JJ, Madan A. Depression following traumatic brain injury: The validity of the CES-D as a brief screening device. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings. 2004;11(3):195–201. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gellis ZD. Assessment of a brief CES-D measure for depression in homebound medically ill older adults. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2010;53(4):289–303. doi: 10.1080/01634371003741417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32(6):705–714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Broadhead WE, Gehlbach SH, de Gruy FV, Kaplan BH. The Duke-UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire. Measurement of social support in family medicine patients. Med Care. 1988;26(7):709–723. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198807000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Henderson S, Duncan-Jones P, Byrne DG, Scott R. Measuring social relationships. The Interview Schedule for Social Interaction. Psychol Med. 1980;10(4):723–734. doi: 10.1017/s003329170005501x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Unden AL, Orth-Gomer K. Development of a social support instrument for use in population surveys. Soc Sci Med. 1989;29(12):1387–1392. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(89)90240-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yuan Y, MacKinnon DP. Bayesian mediation analysis. Psychological methods. 2009;14(4):301–322. doi: 10.1037/a0016972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gelman A, Rubin DB. Inference from iterative simulation using multiple sequences. Statistical Science. 1992;7(4):457–472. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Enders CK. Applied missing data analysis. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rupp AA, Dey DK, Zumbo BD. To Bayes or not to Bayes, from whether to when: Applications of Bayesian methodology to modeling. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2004;11(3):424–451. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Winship C. The perils of multicollinearity: A reassessment. Harvard University; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jagpal HS. Multicollinearity in structural equation models with unobservable variables. Journal of Marketing Research. 1982;19(4):431. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Asparouhov T, Muthen B. Bayesian Analysis of Latent Variable Models using Mplus. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 84.Stekhoven DJ, Bühlmann P. MissForest—non-parametric missing value imputation for mixed-type data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(1):112–118. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Team J. JASP. Version 0.8. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kass RE, Raftery AE. Bayes Factors. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1995;90(430):773–795. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Muthén B, Asparouhov T. Bayesian structural equation modeling: A more flexible representation of substantive theory. Psychol Methods. 2012;17(3):313–335. doi: 10.1037/a0026802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Muthén B, Asparouhov T. Rejoinder to MacCallum, Edwards, and Cai (2012) and Rindskopf (2012): Mastering a new method. Psychological Methods. 2012;17(3):346–353. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cumming G. The new statistics: Why and how. Psychol Sci. 2014;25(1):7–29. doi: 10.1177/0956797613504966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Newcombe RG. Two-sided confidence intervals for the single proportion: Comparison of seven methods. Stat Med. 1998;17(8):857–872. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19980430)17:8<857::aid-sim777>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Dunlap WP, Cortina JM, Vaslow JB, Burke MJ. Meta-analysis of experiments with matched groups or repeated measures designs. Psychological Methods. 1996;1(2):170–177. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences. NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sibbritt DW, Byles JE, Regan C. Factors associated with decline in physical functional health in a cohort of older women. Age and Ageing. 2007;36(4):382–388. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afm017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hansson RO, Stroebe MS. Bereavement in late life: Coping, adaptation, and developmental influences. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Dykstra PA, van Tilburg TG, Gierveld JdJ. Changes in older adult loneliness: Results from a seven-year longitudinal study. Research on Aging. 2005;27(6):725–747. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Jensen MP, Smith AE, Bombardier CH, et al. Social support, depression, and physical disability: Age and diagnostic group effects. Disabil Health J. 2014;7(2):164–172. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Victor C, Scambler S, Bond J, Bowling A. Being alone in later life: Loneliness, social isolation and living alone. Reviews in Clinical Gerontology. 2000;10(4):407–417. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Somhlaba NZ, Wait JW. Stress, coping styles, and spousal bereavement: Exploring pattens of grieving among black widowed spouses in rural South Africa. Journal of Loss and Trauma: International Perspectives on Stress & Coping. 2009;14(3):192–210. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Dean A, Kolody B, Wood P. Effects of Social Support from Various Sources on Depression in Elderly Persons. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1990;31(2):148–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal and the coping process. New York: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Holmes TH, Rahe RH. The social readjustment rating scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1967;11(2):213–218. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(67)90010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Horowitz MJ, Siegel B, Holen A, Bonanno GA, Milbrath C, Stinson CH. Diagnostic criteria for complicated grief disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;154(7):904–910. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.7.904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Schneider DS, Sledge PA, Shuchter SR, Zisook S. Dating and remarriage over the first two years of widowhood. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 1996;8(2):51–57. doi: 10.3109/10401239609148802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Torgrud LJ, Walker JR, Murray L, et al. Deficits in perceived social support associated with generalized social phobia. Cogn Behav Ther. 2004;33(2):87–96. doi: 10.1080/16506070410029577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Stroebe W, Stroebe MS. Bereavement and health: The psychological and physical consequences of partner loss. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bock EW, Webber IL. Suicide among the Elderly: Isolating Widowhood and Mitigating Alternatives. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1972;34(1):24–31. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Dimond M, Lund DA, Caserta MS. The role of social support in the first two years of bereavement in an elderly sample. Gerontologist. 1987;27(5):599–604. doi: 10.1093/geront/27.5.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Morgan LA. A re-examination of widowhood and morale. J Gerontol. 1976;31(6):687–695. doi: 10.1093/geronj/31.6.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kasch KL, Rottenberg J, Arnow BA, Gotlib IH. Behavioral activation and inhibition systems and the severity and course of depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111(4):589–597. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.4.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]