Abstract

The Affordable Care Act requires state Medicaid programs to cover substance use disorder treatment for their Medicaid expansion population but allows states to decide which individual services are reimbursable. To examine how states have defined substance use disorder benefit packages, we used data from 2013–14 that we collected as part of an ongoing nationwide survey of state Medicaid programs. Our findings highlight important state-level differences in coverage for substance use disorder treatment and opioid use disorder medications across the United States. Many states did not cover all levels of care required for effective substance use disorder treatment or medications required for effective opioid use disorder treatment as defined by American Society of Addiction Medicine criteria, which could result in lack of access to needed services for low-income populations.

The expansion of Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) has extended health insurance benefits to an estimated 1.6 million previously uninsured people with substance use disorders.1,2 The law requires states that have adopted the Medicaid expansion to cover substance use disorder treatment in their alternative benefit plans. Furthermore, the Department of Health and Human Services has clarified that federal parity regulations, established by the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008, apply to substance use disorder treatment coverage for enrollees in alternative benefit plans, Medicaid managed care plans, and the Children’s Health Insurance Program.3 To fulfill parity requirements, all state Medicaid programs must ensure that coverage and limits on the use of treatment for substance use disorders are no more restrictive than those placed on other medical and surgical services.4

Combined, the ACA and the mental health parity legislation have the potential to improve access to substance use disorder treatment through Medicaid.5,6 Yet little is known about the specific services state Medicaid programs cover. The essential health benefits (ten categories of services health plans must cover under the ACA) require state Medicaid expansion programs to include coverage for treating substance use disorders in their alternative benefit plans, but the ACA does not specify which services must be included. Moreover, because the ACA does not mandate essential health benefits for traditional Medicaid enrollees, state traditional Medicaid programs maintain broad discretion over substance use disorder benefit decisions. To examine how states have defined substance use disorder benefit packages, we analyzed data from 2013–14 that we collected as part of an ongoing survey of state Medicaid programs.

As with all insurance programs, benefit design decisions within Medicaid influence access to care7,8 and can potentially affect health outcomes.9,10 As Medicaid is poised to become the largest payer of substance use disorder treatment in the United States,11,12 such decisions are also likely to influence whether treatment providers decide to offer particular services.5,13 Given the importance of Medicaid substance use disorder benefit policies, our study compared state decisions for such coverage against American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) clinical guidelines for substance use disorder services.

ASAM began developing a national set of criteria for the treatment of addiction in the 1980s. Numerous validation studies have established that matching the severity of a patient’s substance use disorder to the levels of care specified in the ASAM criteria optimizes treatment processes and outcomes.14 Based on this research, there is now considerable clinical and scientific consensus regarding the continuum of care, and the ASAM criteria are now the most widely used and evaluated set of guidelines for treating patients with substance use disorders.15,16 The majority of states (66 percent) require state block grant–funded providers of substance use disorder treatment to use the ASAM criteria,17 and many private health care plans use the ASAM criteria to determine medical necessity care guidelines.18,19 Moreover, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) recently sent a notification letter to state Medicaid directors, informing them that to receive approval for the section 1115 waiver for innovative service delivery in substance use disorders, “states must implement a process to assess and demonstrate that residential providers meet ASAM Criteria prior to participating in the Medicaid program.” This statement indicates that CMS also views the ASAM criteria as a legitimate clinical guideline.20

The ASAM criteria specify four levels of care that are essential for effective treatment of substance use disorders: level 1 outpatient services, level 2 intensive outpatient services, level 3 residential inpatient services, and level 4 intensive inpatient services (see online Appendix A1).21

Additionally, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved four medications that can be used in combination with psychosocial treatment for effective treatment of opioid use disorders.22–24 These medications are methadone, buprenorphine, and both oral and extended-release injectable naltrexone. ASAM’s practice guideline for these medications suggests that each one is important to the provider toolkit because the presenting symptoms of patients vary.22

The ASAM guideline also recommends that all opioid use disorder medications be offered in conjunction with the appropriate level of psychosocial treatment, which is most often delivered in the context of outpatient treatment (either level 1 outpatient or level 2 intensive outpatient).

Because states retain discretion under the ACA to select the specific substance use disorder treatment services and opioid use disorder medications they cover within their Medicaid programs, the extent to which state Medicaid coverage for substance use disorder treatment aligns with the ASAM clinical guidelines is unclear. Given the importance of these policy choices, our study examined state coverage decisions regarding the continuum of substance use disorder treatment services across the ASAM criteria and evidence-based medications for opioid use disorder treatment, as well as combined availability of opioid use disorder medications and concurrent outpatient substance use disorder treatment. The study also examined the extent to which state Medicaid programs imposed usage limits on the services they covered. Finally, for those states that adopted the Medicaid expansion, the study explored whether state coverage of disorder treatment services for newly eligible people differed from that offered to traditional Medicaid enrollees.

Study Data And Methods

Data

Data were collected as part of the National Drug Abuse Treatment System Survey (NDATSS), a panel study of substance use disorder treatment providers which has been conducted periodically since 1984. We used the 2013 survey, which included an Internet survey administered to state Medicaid programs in the fifty states and the District of Columbia. Each Medicaid director was mailed a packet that contained a study description and an invitation to participate or to designate a knowledgeable staff person to participate. Follow-up e-mails and phone calls were made to directors who did not respond to the packet or the initial e-mail.

Data were collected from November 2013 through December 2014 from forty-seven of the nation’s fifty-one Medicaid programs. Four state Medicaid programs opted not to complete the survey but shared documentation regarding their agency’s substance use disorder treatment service benefits that enabled our research staff to complete the survey on their behalf.

To reduce the data collection burden on Medicaid staff, an analysis of all fifty-one Medicaid plans on file with CMS and agency websites was conducted to prefill our survey information to the extent possible before sending the survey to the state Medicaid programs. Survey instructions explained to respondents that some responses were prefilled and asked them to confirm whether the responses were correct.

In the case of methadone, buprenorphine, and injectable naltrexone, coverage data collected by ASAM were used. ASAM used data collected from state Medicaid agencies and published state formularies to determine which of these opioid use disorder medications were covered and whether limits were imposed. When preauthorization limits and annual maximum limits were not specified, we used our survey data on coverage limitations.

The federal government should consider a financial incentive for states to cover services across the ASAM levels of care.

State Medicaid coverage decisions were assessed for services included in the ASAM criteria:25 level 1 outpatient treatment: individual and group outpatient treatment, recovery support services; level 2 intensive outpatient treatment: intensive outpatient treatment; level 3 residential treatment: short-term and long-term residential treatment; and level 4 medically managed inpatient treatment: inpatient detoxification (see Appendix A1 for an illustration of the levels of care).21 Coverage decisions were also assessed for the four FDA-approved opioid use disorder medications.

For each of these services and medications, information on the following utilization control limits was collected: cost sharing, including copayments and deductibles; preauthorization; and annual maximums. These utilization management mechanisms are commonly used by private and public health plans to control unnecessary usage. Finally, for those state Medicaid programs participating in the ACA’s Medicaid expansion, the questionnaire asked whether the alternative benefit plans offered to Medicaid expansion enrollees differed from traditional Medicaid benefits with regard to the types of services covered and the use of service utilization limits. At the time of our study, twenty states and the District of Columbia had expanded Medicaid; for a list of the states, see Appendix A2.21

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, almost all states contract with managed care organizations representing at least a portion of their Medicaid enrollees (77 percent of total state Medicaid enrollment as of 2014),26 and these organizations are allowed to set their own limitation policies. While state contracts with managed care organizations specify coverage of some or most of the benefits that are covered under their state plans, states and managed care organizations also might agree to give contracted organizations added flexibility to cover services “in lieu of” services specified under the state plan but permissible under Medicaid.27 In practice, a state’s Medicaid managed care system could conceivably cover services in addition to those covered under the state plan. Because our data were based on the state Medicaid plans (and confirmed by Medicaid agency staff), they reflect the minimum substance use disorder services covered in the state. However, managed care organizations might have more stringent limit policies (such as preauthorization). Yet they still are required at a minimum to offer the covered services specified in the state Medicaid plan. It is clear that coverage alone does not necessarily denote access to services, which is why we also asked about state limitation policies. Nonetheless, it is important to acknowledge that we do not have data on managed care organizations’ limitation policies.

Second, our data collection method relied on information specified in state Medicaid plans submitted for approval to CMS and review of the accuracy of these data by a staff representative in each state’s Medicaid program office. We expected this two-pronged approach to minimize data error. However, if state information was incorrectly entered in the state plan and the staff representative was unaware of the error or unaware of updates not reflected in the state plan, some errors might have been included in the data. Also, in four states we had only the state plan data and lacked the staff review of those data. If these states updated their substance use disorder coverage policies after submitting the plan to CMS, our data would be inaccurate.

Third, the survey questions did not ask about all possible substance use disorder services or medications, or all possible ways to limit coverage. We asked about the services most pertinent under the ASAM criteria and the medications considered most important to treat opioid use disorders, but we do not suggest that our study has captured all of the important services or medications. Moreover, states might limit coverage in ways we did not capture, such as through the use of coinsurance.

Fourth, the survey questions assumed uniformity in Medicaid coverage across subpopulations of Medicaid enrollees and across geographic regions, and thus did not account for possible variations in coverage among enrollees living in the same state. For example, if a state had a waiver to vary benefits by region28 or by population group (about ten states as of 2012)29 and chose to vary coverage for substance use disorders, that variation would not be captured in our analyses.

Finally, because state policy data do not reveal how frequently limitation policies (preauthorization, annual maximums, and copayments) are used or how they are employed, we could not make evaluative judgments about these policies.

Study Results

Coverage Across Criteria

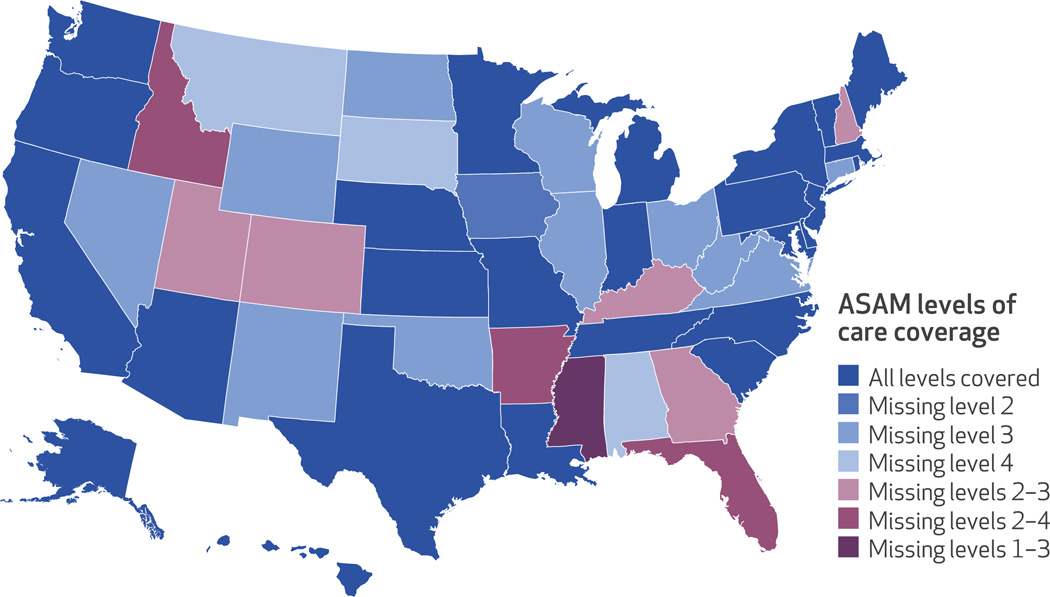

Twenty-six states and the District of Columbia provided coverage for at least one service in each of the four levels of care specified in the ASAM criteria. Thirteen states and the District of Columbia covered all seven services across the four levels of care—a comprehensive package of substance use disorder services. Among the other twenty-four states, fifteen lacked coverage in at least one level of care, five lacked coverage in two levels of care, and four lacked coverage in three levels of care (Exhibit 1). (For additional details, see Appendix A1.)21

Exhibit 1. State coverage of the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) continuum of care levels.

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of National Drug Abuse Treatment System Survey data, 2013–14. NOTE The District of Columbia provides coverage across all levels of care.

Among states that limited coverage, it was most common to restrict level 3 residential treatment. Twenty-one states provided no short- or long-term residential services. Ten states did not cover level 2 intensive outpatient services, and nine of the twenty-four states that limited coverage did not cover any services in levels 2 or 3. Finally, six states offered no coverage of level 4 medically managed inpatient services.

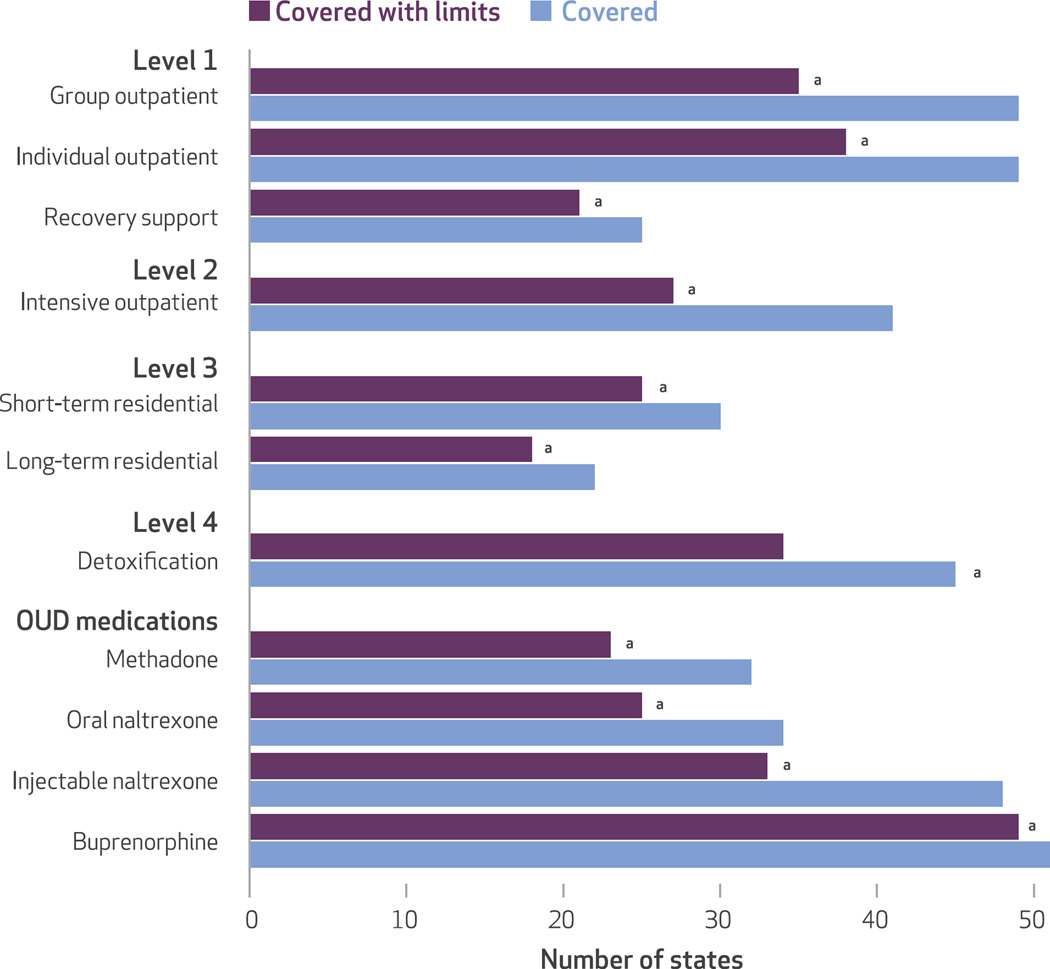

Almost all states and the District of Columbia covered two of the three services listed under level 1 individual and group outpatient treatment services. Although coverage of these outpatient services is common, only half of the states and the District of Columbia provided Medicaid-funded recovery support services (Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2. State coverage across the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) continuum of care levels and opioid use disorder (OUD) medications.

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of National Drug Abuse Treatment System Survey data, 2013–14. NOTE “Covered with limits” means that a state covers the service but imposes limits by either using prior authorization, annual maximum limits, or copayments and deductibles. aIncludes the District of Columbia.

Coverage Of Medications For Opioid Use Disorders

Medicaid programs in all states and the District of Columbia (n = 51) provided coverage for buprenorphine, and almost all states and the District of Columbia (n = 48) covered injectable naltrexone. However, there was much less widespread coverage for oral naltrexone (n = 34) and methadone (n = 32) (Exhibit 2).

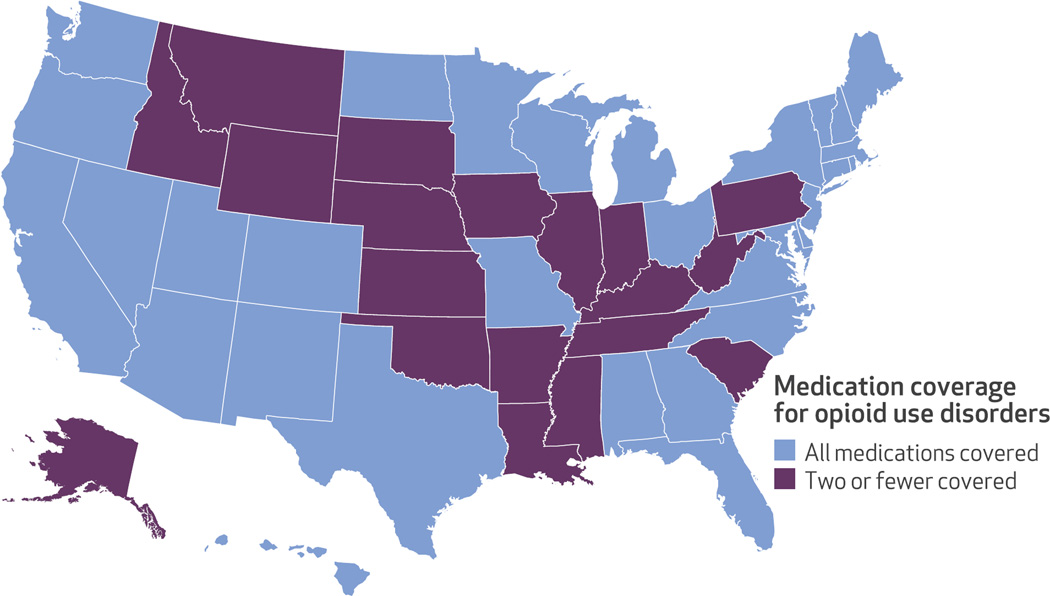

Looking at coverage of the four opioid use disorder medications, thirty-one states and the District of Columbia provided comprehensive coverage: methadone, buprenorphine, and one (n = 10) or both (n = 22) of the two forms of naltrexone. The remaining nineteen states did not provide comprehensive medication coverage for opioid use disorders; most notably, they did not cover methadone treatment (Exhibit 3). Eleven of these nineteen states provided coverage for buprenorphine and both forms of naltrexone. Six states covered buprenorphine and injectable naltrexone, and two states covered only buprenorphine (data not shown).

Exhibit 3. State coverage of opioid use disorder medications.

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of National Drug Abuse Treatment System Survey data, 2013–14. NOTE The District of Columbia provides coverage for all medications.

Combined Coverage

Seventeen states and the District of Columbia covered the entire package of opioid use disorder medications and all three treatments across levels 1 and 2 (individual and group outpatient and intensive outpatient). An additional seven states offered most medications (methadone, buprenorphine, and injectable naltrexone) and all three treatment services. The remaining half of the states (n = 26) either lacked coverage of any of the four medications or lacked coverage of outpatient treatment.

No statistically significant relationship was detected between coverage of substance use disorder services across the ASAM criteria and coverage of opioid use disorder medications. States that had comprehensive coverage across the ASAM criteria did not necessarily have comprehensive coverage for opioid use disorder medications. Only eighteen states and the District of Columbia provided comprehensive coverage across the ASAM criteria and opioid use disorder medications. The remaining thirty-two states lacked coverage across the ASAM levels of care or medications for treatment of opioid use disorders, or both.

Limits On Substance Use Disorder Services And Opioid Use Disorder Medications

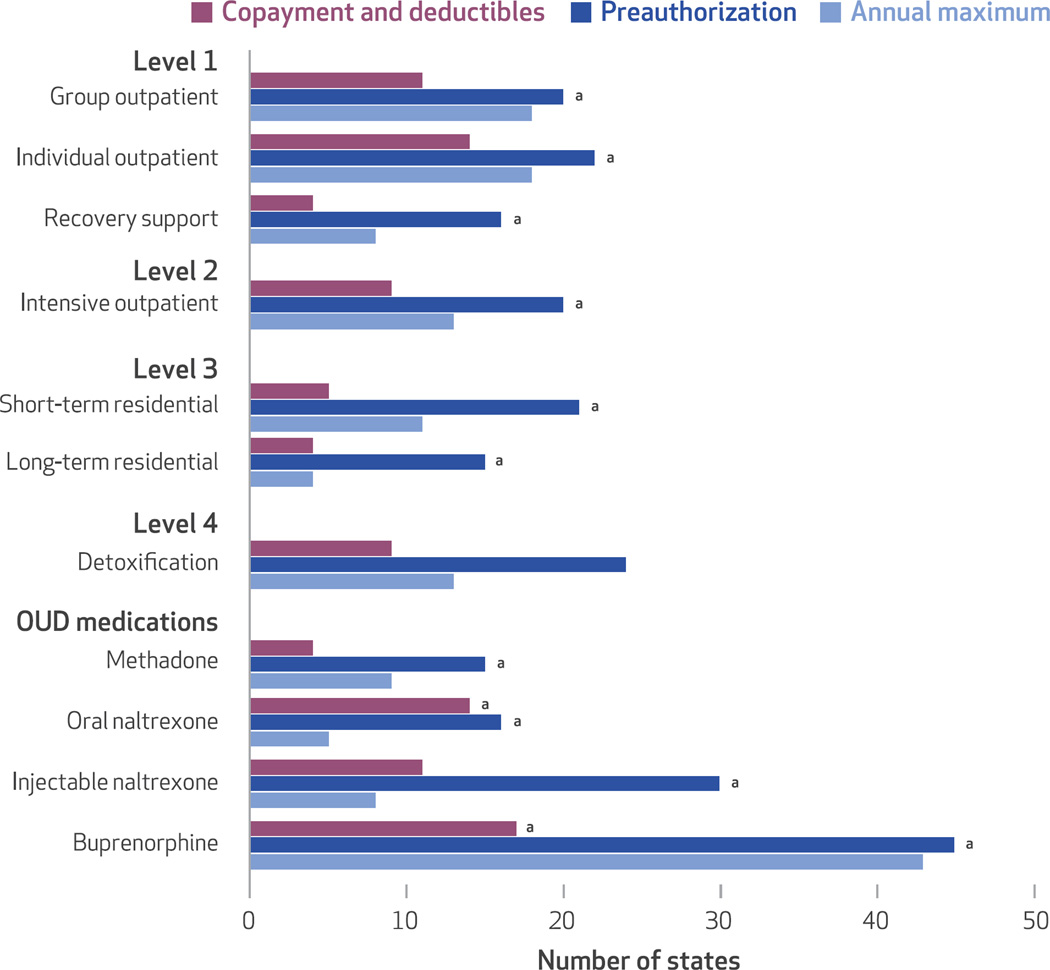

The vast majority of state and the District of Columbia Medicaid programs set limits on covered substance use disorder treatment services (Exhibit 4). Coverage for short-term residential, long-term residential, and recovery support services was limited under Medicaid in more than 80 percent of states and the District of Columbia. Buprenorphine was the most prominent example among opioid use disorder medications, with limits imposed in all but one state. The most common way states set limits was to require preauthorization. Many states also imposed annual maximums on service coverage. While this approach is common, the specific rules for setting annual maximums varied dramatically across states and across services and medications. For example, state annual maximum rules for individual outpatient services ranged from twelve visits per year before preauthorization was required, to twenty-six hours total, to thirty-two quarter-hour units per week, to 365 treatments per year.

Exhibit 4. Types of limits imposed on substance use disorder services across the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) continuum of care levels and opioid use disorder (OUD) medications.

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of National Drug Abuse Treatment System Survey data, 2013–14. aIncludes the District of Columbia.

Copayments and deductibles were uncommon for substance use disorder treatment benefits in state and the District of Columbia Medicaid programs. Nonetheless, cost sharing was required for buprenorphine in sixteen states and the District of Columbia and for oral naltrexone and individual outpatient services in thirteen states and the District of Columbia.

Alternative Benefits

Among the twenty-five states and the District of Columbia that expanded Medicaid at the time of this survey, only five states offered different substance use disorder treatment coverage for the expansion group. There was no clear pattern within this small group of states. The alternative benefit plan for new enrollees was more generous in two states, whereas in three others it was more restrictive. In the remainder of expansion states, coverage was the same between traditional enrollees and those people newly eligible. However, many states indicated that they were working on developing their alternative benefit plan at the time of our survey, so the number of states with distinctive alternative benefit plans for newly eligible people might have increased.

Discussion

Our findings highlight important state-level disparities in coverage for substance use disorder treatment across the United States. Many states do not cover all levels of care required for effective treatment, as defined by the ASAM criteria—a well-researched, widely endorsed national standard of care. For treatment providers, limited coverage for the full continuum of treatment settings and modalities constrains their ability to make optimal treatment decisions.

These state decisions regarding benefit coverage of substance use disorder services and opioid use disorder medications have real-world consequences for patients with addictive disorders.9,10 For example, if a patient is assessed as “needs close monitoring,” the patient will be at high risk for relapse in the twenty-one states that do not cover residential treatment and in the nine states that do not cover either level 3 residential or level 2 intensive outpatient services.

Moreover, while all fifty-one Medicaid programs cover buprenorphine and forty-seven states and the District of Columbia cover injectable naltrexone, lack of coverage of all four opioid use disorder medications can still cause problems for people with opioid use disorders. Although these two treatments are effective, methadone—the medication covered by the fewest states—remains the most efficacious and rigorously studied medication in the armamentarium.30 Just as there are multiple medications to treat hypertension, effective treatment of opioid use disorders requires access to the full range of effective medications.

Finally, the widespread use of limitation policies such as preauthorization and significant variation in how annual maximums are set raise concerns about what clinical guidelines are used to determine limits and whether access to needed substance use disorder services are unnecessarily or inappropriately denied.31,32 Given that the use of preauthorization policies has been linked to underuse of mental health and substance use disorder services,33–36 the lack of knowledge about how states impose limits and what clinical reasoning is used when services are denied underscores the need for further research on the effect of limitation policies.

Policy Implications

The fact that so many states do not cover level 3 residential services points to a larger tension in federal Medicaid policy, which generally prohibits the use of federal Medicaid funds to cover Medicaid enrollees in institutions for mental diseases (IMDs) with more than sixteen beds (the so-called IMD exclusion). Although states can provide coverage for smaller facilities providing residential services or for care in larger settings that would not be defined as IMDs, this federal policy is one clear barrier to Medicaid-funded residential services and might explain why many states choose not to provide any Medicaid-funded residential coverage. While the federal government has recently relaxed the IMD exclusion for inpatient stays of fifteen days or fewer,37 the long-term impact of the policy change remains to be studied.

CMS’s notification letter regarding substance use disorder delivery-of-care waivers and the requirement to use the ASAM criteria is a first step toward aligning CMS policies with clinical standards for substance use disorder care. However, because states are accorded wide discretion in coverage policy, the federal government should consider a financial incentive for states to cover services across the ASAM levels of care, regardless of whether the state submits a waiver. Similarly, the federal government should consider financial incentives for states to cover all four effective medications for opioid use disorders.

Conclusion

Our findings highlight important state-level disparities in coverage decisions for substance use disorder treatments and opioid use disorder medications across the United States. When levels of care are not covered, Medicaid-eligible patients might not be able to gain access to needed services. Patients without access to the full range of efficacious services or medications are more likely to be mismanaged or treated in inappropriate settings.38–40 Consequently, they are put at higher risk for relapse, which has serious public health implications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health (Grant No. R01DA034634), for its project, “The impact of health reform on outpatient substance abuse treatment programs,” although the recommendations and responsibility for any errors rest solely with the authors. The authors acknowledge data collection support from the University of Chicago Survey Lab and helpful feedback from Sara Rosenbaum, the editors of Health Affairs, and three anonymous reviewers.

Contributor Information

Colleen M. Grogan, School of Social Service Administration, University of Chicago, in Illinois..

Christina Andrews, College of Social Work, University of South Carolina, in Columbia..

Amanda Abraham, Department of Public Administration and Policy at the University of Georgia, in Athens..

Keith Humphreys, Department of Psychiatry at the Stanford School of Medicine, in California..

Harold A. Pollack, School of Social Service Administration, University of Chicago..

Bikki Tran Smith, School of Social Service Administration, University of Chicago..

Peter D. Friedmann, Baystate Health, in Springfield, Massachusetts..

NOTES

- 1.Barry CL, Huskamp HA. Moving beyond parity—mental health and addiction care under the ACA. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(11):973–975. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1108649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Humphreys K, Frank RG. The Affordable Care Act will revolutionize care for substance use disorders in the United States. Addiction. 2014;109(12):1957–1958. doi: 10.1111/add.12606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Baltimore (MD): CMS; 2016. Mar 29, [[cited on 2016 Oct 26]]. Medicaid fact sheet: mental health and substance use disorder parity final rule for Medicaid and CHIP [Internet] (SMD No. 2333-f). Available from: https://staging.medicaid.gov/medicaid/benefits/downloads/factsheet-cms-2333-f.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beronio K, Po R, Skopec L, Glied S. Washington (DC): Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation; 2013. Feb 20, [cited 2016 Oct 13]. Affordable Care Act expands mental health and substance use disorder benefits and federal parity protections for 62 million Americans [Internet] Available from: https://aspe.hhs.gov/report/affordable-care-act-expands-mental-health-and-substance-use-disorder-benefits-and-federal-parity-protections-62-million-americans. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andrews C, Grogan CM, Brennan M, Pollack HA. Lessons from Medicaid’s divergent paths on mental health and addiction services. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015;34(7):1131–1138. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buck JA. The looming expansion and transformation of public substance abuse treatment under the Affordable Care Act. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30(8):1402–1410. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deck DD, Wiitala WL, Laws KE. Medicaid coverage and access to publicly funded opiate treatment. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2006;33(3):324–334. doi: 10.1007/s11414-006-9018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wen H, Druss BG, Cummings JR. Effect of Medicaid expansions on health insurance coverage and access to care among low-income adults with behavioral health conditions. Health Serv Res. 2015;50(6):1787–1809. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fuller BE, Rieckmann TR, McCarty DJ, Ringor-Carty R, Kennard S. Elimination of methadone benefits in the Oregon health plan and its effects on patients. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(5):686–691. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.5.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stein B, Orlando M, Sturm R. The effect of copayments on drug and alcohol treatment following inpatient detoxification under managed care. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51(2):195–198. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.51.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andrews C, Abraham A, Grogan CM, Pollack HA, Bersamira C, Humphreys K, et al. Despite resources from the ACA, most states do little to help addiction treatment programs implement health care reform. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015;34(5):828–835. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mark TL, Levit KR, Yee T, Chow CM. Spending on mental and substance use disorders projected to grow more slowly than all health spending through 2020. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33(8):1407–1415. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ducharme LJ, Abraham AJ. State policy influence on the early diffusion of buprenorphine in community treatment programs. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2008;3(1):17. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-3-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stallvik M, Gastfriend DR. Predictive and convergent validity of the ASAM criteria software in Norway. Addict Res Theory. 2014;22(6):515–523. [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Society of Addiction Medicine. The ASAM criteria [Internet] Chevy Chase (MD): ASAM; [cited 2016 Oct 13]. Available from: http://www.asam.org/publications/the-asam-criteria/about. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chuang E, Wells R, Alexander JA, Friedmann PD, Lee IH. Factors associated with use of ASAM criteria and service provision in a national sample of outpatient substance abuse treatment units. J Addict Med. 2009;3(3):139–150. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e31818ebb6f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kolsky GD. Current state AOD agency practices regarding the use of patient placement criteria (PPC)—an update [Internet] Washington (DC): National Association of State Alcohol and Drug Abuse; 2006. Nov 6, [cited 2016 Oct 13]. Available from: http://www.asam.org/docs/publications/survey_of_state_use_of_ppc_nasadad-2006.pdf?Status=Master. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blue Cross Blue Shield of Illinois. Behavioral health medical necessity criteria [Internet] Chicago (IL): BCBS of Illinois; [cited 2016 Oct 13]. Available from: http://www.bcbsil.com/provider/clinical/medical_necessity.html. [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Society of Addiction Medicine. An introduction to the ASAM criteria for patients and families [Internet] Hartford (CT): Aetna; 2015. [cited 2016 Oct 13]. Available from: http://www.aetna.com/healthcare-professionals/documents-forms/asam-criteria.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wachino V. Baltimore (MD): Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; 2015. Jul 27, [cited on 2016 Oct 12]. New service delivery opportunities for individuals with a substance use disorder [Internet] (SMD No. 15-003). Available from: https://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/SMD15003.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 21.To access the Appendix, click on the Appendix link in the box to the right of the article online.

- 22.Kampman K, Jarvis M. American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) national practice guideline for the use of medications in the treatment of addiction involving opioid use. J Addict Med. 2015;9(5):358–367. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Rockville (MD): SAMHSA; 2015. [cited 2016 Oct 13]. Medication for the treatment of alcohol use disorder: a brief guide [Internet] Available from: http://store.samhsa.gov/shin/content//SMA15-4907/SMA15-4907.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mann C, Frieden T, Hyde PS, Volkow ND, Koob GF. Baltimore (MD): Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; 2014. Jul 11, [cited on 2016 Oct 13]. Medication assisted treatment for substance use disorders [Internet] Available from: https://www.medicaid.gov/Federal-Policy-Guidance/Downloads/CIB-07-11-2014.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mee-Lee D. The ASAM criteria: treatment criteria for addictive, substance-related, and co-occurring conditions. Third. Chevy Chase (MD): American Society of Addiction Medicine; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation. State health facts: total Medicaid managed care enrollment [Internet] Menlo Park (CA): KFF; 2014. [cited 2016 Oct 13]. Available from: http://kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/total-medicaid-mc-enrollment/ [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosenbaum S. Twenty-first century Medicaid: the final managed care rule. [cited 2016 Oct 13];Health Affairs Blog [blog on the Internet] 2016 May 5; Available from: http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2016/05/05/twenty-first-century-medicaid-the-final-managed-care-rule/ [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hanson KW, Huskamp HA. State health care reform: behavioral health services under Medicaid managed care: the uncertain implications of state variation. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(4):447–450. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.4.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation. State health facts: Medicaid benefits: rehabilitation services—mental health and substance abuse [Internet] Menlo Park (CA): KFF; 2014. [cited 2016 Oct 13]. Available from: http://kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/rehabilitation-services-mental-health-and-substance-abuse/ [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, Davoli M. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(2):CD002207. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002207.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Rockville (MD): SAMHSA; 2014. [cited 2016 Oct 13]. Medicaid coverage and financing of medications to treat alcohol and opioid use disorders [Internet] Available from: http://store.samhsa.gov/shin/content//SMA14-4854/SMA14-4854.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pew Charitable Trusts. Substance use disorders and the role of the states [Internet] Washington (DC): Pew Charitable Trusts; 2015. Mar, [cited 2016 Oct 13]. Available from: http://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/assets/2015/03/substanceusedisordersandtheroleofthestates.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clark RE, Baxter JD, Barton BA, Aweh G, O’Connell E, Fisher WH. The impact of prior authorization on buprenorphine dose, relapse rates, and cost for Massachusetts Medicaid beneficiaries with opioid dependence. Health Serv Res. 2014;49(6):1964–1979. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mark TL, Lubran R, McCance-Katz EF, Chalk M, Richardson J. Medicaid coverage of medications to treat alcohol and opioid dependence. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2015;55:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2015.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vogt WB, Joyce G, Xia J, Dirani R, Wan G, Goldman DP. Medicaid cost control measures aimed at second-generation antipsychotics led to less use of all antipsychotics. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30(12):2346–2354. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang Y, Adams AS, Ross-Degnan D, Zhang F, Soumerai SB. Effects of prior authorization on medication discontinuation among Medicaid beneficiaries with bipolar disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(4):520–527. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.4.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Whitlock R. The IMD exclusion: changes now and changes to come. [cited 2016 Oct 13];Health Law and Policy Matters [blog on the Internet] 2016 Apr 27; Available from: https://www.healthlawpolicymatters.com/2016/04/27/the-imdexclusion-changes-now-and-changes-to-come/ [Google Scholar]

- 38.Capoccia VA, Grazier KL, Toal C, Ford JH, 2nd, Gustafson DH. Massachusetts’s experience suggests coverage alone is insufficient to increase addiction disorders treatment. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31(5):1000–1008. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garfield RL, Lave JR, Donohue JM. Health reform and the scope of benefits for mental health and substance use disorder services. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(11):1081–1086. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.11.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Rockville (MD): SAMHSA; 2014. [cited 2016 Oct 13]. Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: summary of national findings [Internet] Available from: http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUHresultsPDFWHTML2013/Web/NSDUHresults2013.pdf. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.