Summary

Mitochondrial ATP synthesis, calcium buffering, and trafficking affect neuronal function and survival. Several genes implicated in mitochondrial functions map within the genomic region associated with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (22q11DS), which is a key genetic cause of neuropsychiatric diseases. Although neuropsychiatric diseases impose a serious health and economic burden, their etiology and pathogenesis remain largely unknown because of the dearth of valid animal models and challenges in investigating the pathophysiology in neuronal circuits. Mouse models of 22q11DS are becoming valid tools for studying human psychiatric diseases, because they have hemizygous deletions of the genes that are deleted in patients and exhibit neuronal and behavioral abnormalities consistent with neuropsychiatric disease. The deletion of some 22q11DS genes implicated in mitochondrial function leads to abnormal neuronal and synaptic function. Herein, we summarize recent findings on mitochondrial dysfunction in 22q11DS and extend those findings to the larger context of schizophrenia and other neuropsychiatric diseases.

Keywords: 22q11.2 deletion syndrome, schizophrenia, mitochondria, synapse, synaptic plasticity, calcium, ATP

Introduction

Serious mental illness affects an estimated 9.8 million adults in the United States, which represents 4.2% of the nation’s adult population [1]. Globally, 7.4% of all disability-adjusted life years, a measure of time lost due to health problems, disability, or early death, is caused by mental and behavioral disorders [2]. In the United States, mental health disorders are associated with the highest economic burden, accounting for $201 billion in annual healthcare spending [3]. Despite the severity of these disabilities and the associated economic burden, progress in the field of neuropsychiatry has been hampered by the complexity of higher-order neurobiological functions and the dearth of valid animal or cellular models of psychiatric diseases [4].

Mouse models of 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (22q11DS) hold promise to increase our understanding of the complex biology of mental illnesses [5–7]. 22q11DS (also known as velocardiofacial or DiGeorge syndrome) is the most common microdeletion syndrome in humans [8–10], with a prevalence of 1 in 4000 live births. The syndrome is caused by a hemizygous microdeletion (1.5–3 Mb) on the long arm of chromosome 22 [11]. It is one of the strongest genetic risk factors for schizophrenia [12,13]. Schizophrenia develops in 23% to 43% of individuals with 22q11DS [14–18], most of whom experience psychosis [19,20]. Furthermore, 30% to 50% of nonschizophrenic individuals with 22q11DS exhibit subthreshold symptoms of psychosis [21]. Nonpsychotic behavioral abnormalities are present from early adulthood in patients with 22q11DS [22,23], but psychotic symptoms and schizophrenia appear only in adulthood [24–26]. In addition to schizophrenia, 25% to 50% of individuals with 22q11DS exhibit comorbid illnesses such as attention-deficit hyperactive disorder, autism spectrum disorder, anxiety, and mood disorders [27,28]. The varied outcomes of patients with this syndrome suggest deficits in multiple neural circuits.

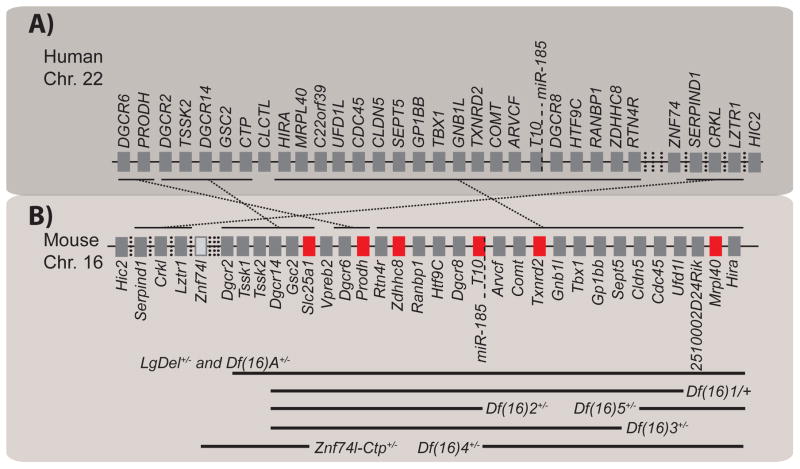

All genes within the human 22q11.2 genomic region, except for one, are present on mouse chromosome 16 but in a slightly shuffled order. Mouse models with deletions spanning different syntenic regions have been developed over the past several years (Fig. 1) [29]. The availability of these mouse models and the overlap of different neuropsychiatric phenotypes with 22q11DS provide a valuable experimental tool to dissect the genetic causes and investigate the molecular and cellular mechanisms of these phenotypes [29,30]. Using mouse models of 22q11DS (22q11DS mice), our group investigated the genetic causes of neural circuit deficits that give rise to abnormalities that resemble the cognitive and positive symptoms of schizophrenia [31–33]. Several groups have reported working-memory deficits in patients with 22q11DS and in 22q11DS mice [34–37]. We recently identified that haploinsufficiency of the 22q11DS gene Mrpl40 contributes to working-memory deficits. Mrpl40 encodes one of the mitochondrial proteins in the large ribosomal subunit [34]. Zdhhc8, another putative mitochondrial gene within the 22q11 genomic region, has also been implicated in a working-memory disorder [38]. Prodh, a gene encoding mitochondrial proline dehydrogenase, has been implicated in deficient sensorimotor gating [39]. Altogether, six 22q11DS genes—Prodh, Slc25a1, Mrpl40, Zdhhc8, T10, and Txnrd2—encode mitochondrial proteins (Fig. 1B). Computational predictions suggest that three other 22q11DS genes—Gnbl1, Rtn4r, and Ufd1l— also encode proteins that are important for mitochondria [40]. On the basis of these findings, we propose that the mitochondrion is most likely a key organelle in the pathophysiology of 22q11DS and schizophrenia.

Figure 1. Mouse models of 22q11DS and mitochondrial genes.

(A, B) Genes hemizygously deleted on chromosome (Chr.) 22 in human patients (A) and on chromosome 16 in mouse models of 22q11DS (B). The genes important for mitochondrial function are labeled in red (B). Hemizygous deletions spanning different subregions in mouse models are indicated by solid black lines.

An analysis of several published studies on genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic factors associated with schizophrenia revealed 295 genes that mediate mitochondrial structure or function [41]. Moreover, 57 of those genes have been implicated in more than one study [41]. Twenty-two genes encoding mitochondrial proteins have been mapped within the 108 genetic risk loci (encompassing more than 300 genes) and were identified by the largest schizophrenia genome-wide association study (GWAS) to date [41–43]. This preponderant association of mitochondrial genes with schizophrenia and 22q11DS justifies further testing of the hypothesis that complex psychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia, have a mitochondrial origin. This hypothesis has been strengthened by a recent proteomics and metabolomics study that identified multiple mitochondrial proteins that are deregulated in 22q11DS mice [44]. The intertwining of mitochondrial function with multiple cellular processes is also considered a common denominator in various psychiatric disorders [45,46]. The comorbidity of mitochondrial disorders and autism, depression, anxiety, or bipolar disorder is well established [46]. Although these disorders may not qualify as classic mitochondrial diseases, many abnormal proteins encoded by nuclear genes can affect mitochondrial function, thereby compromising the functioning of neural circuits [45].

In this essay, we summarize recent findings on the interdependence of mitochondrial and neural functions. Furthermore, we discuss how defects in 22q11DS nuclear-encoded genes may affect mitochondrial function in neural circuits and lead to the neuropathophysiology associated with 22q11DS symptoms. We also touch upon how mitochondrial functions vary across cell types in the central nervous system (CNS).

Mitochondrial and neuronal functions are interdependent

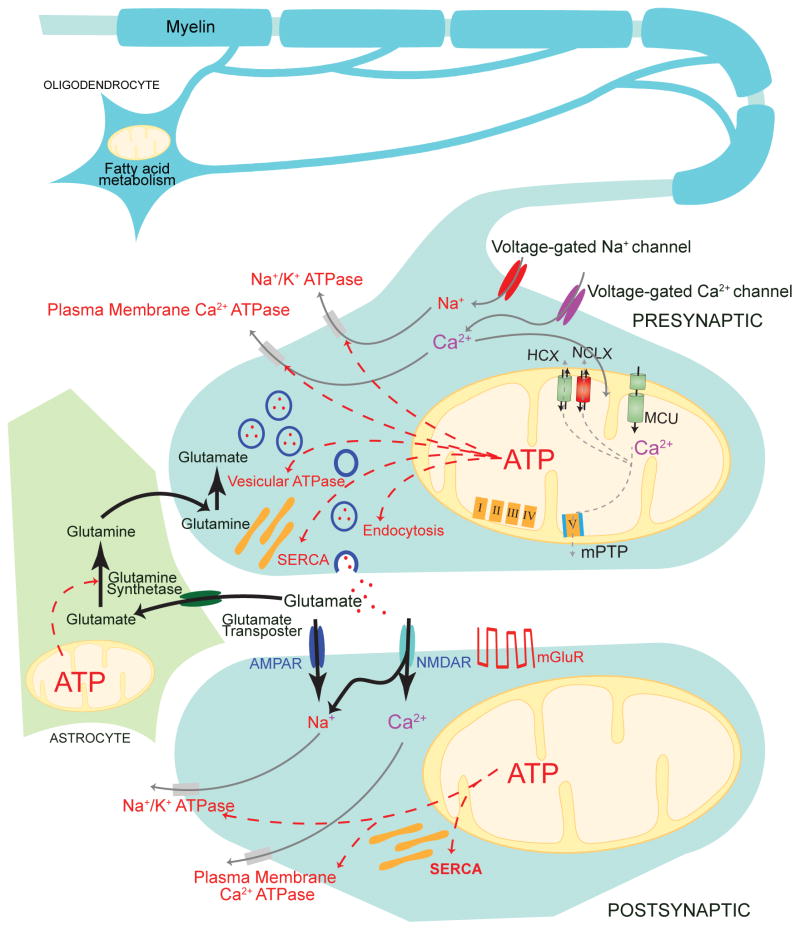

Synaptic transmission and plasticity in neural circuits are highly energy-dependent processes. Mitochondria, the primary cellular organelles that provide adenosine triphosphate (ATP), also partake in other neuronal functions at the synapse, such as calcium buffering, lipid biogenesis, and redox regulation (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Interdependence of synaptic and mitochondrial functions.

Presynaptically, adenosine triphosphate (ATP) derived from mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation is used by the sodium–potassium ATPase for maintaining the resting membrane potential, various ATPases that restore cytosolic calcium levels after action potentials, vesicular ATPases (vATPases) that load neurotransmitters into vesicles, and vesicular endocytosis. Postsynaptically, ATP is consumed primarily for pumping out the ions that mediate synaptic currents. Presynaptic mitochondria also play an important role in the calcium buffering mediated by the mitochondrial calcium uniporter (MCU) complex, the sodium–calcium exchanger (NCLX), the proton–calcium exchanger (HCLX), and the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP). In astrocytes, an important consumer of ATP is glutamine synthetase, which is needed to maintain the glutamate–glutamine cycle. In oligodendrocytes, mitochondrial lipid metabolism plays a role in myelination. AMPAR; α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor; mGluR, metabotropic glutamate receptor; NMDAR, N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor;SERCA, (sacro)endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase.

Mitochondrial ATP supports synaptic function

The electrochemical nature of synaptic signaling makes the process a big ATP consumer [47]. ATP is required primarily by the sodium–potassium ATPases, which maintain the resting membrane potential in neurons; various calcium pumps [e.g., plasma membrane and (sarco)endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2 (SERCA2)], which maintain low cytosolic calcium concentration; vesicular ATPases (vATPases), which fill synaptic vesicles with neurotransmitters; and synaptic vesicle exocytosis and endocytosis [47]. A recent study showed that under conditions of ATP depletion synaptic vesicle endocytosis is the most affected event [48]. In that study, activity-dependent synaptic ATP consumption was measured in individual presynaptic terminals by using the synaptically targeted luciferase reporter Syn-ATP [48]. Neurotransmitters are loaded into vesicles by vesicular transporters, which are aided by vacuolar ATPases. These molecular complexes have the same architecture as mitochondrial ATP synthase (also an ATPase) but are oriented in the opposite direction. This converse orientation enables the complexes to use the energy derived from ATP hydrolysis to drive a motor that generates a proton and pH gradient to help load the neurotransmitters into vesicles [49]. Single-vesicle imaging has shown that glutamate and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), two major neurotransmitters in the mammalian brain, are loaded into vesicles by different classes of vesicular transporters. Compared with glutamate transporters, GABA vesicular transporters rely more on the proton gradient generated by vATPases for loading, which suggests that excitatory neurons and inhibitory neurons have different needs for vATPases [50]. Apart from its role as an energy currency, ATP also acts as a neurotransmitter and activates purinergic receptors [51]. Moreover, ATP degradation leads to the production of adenosine, another important neurotransmitter, which acts through various adenosine-specific receptors [51]. In turn, adenosine is released from neurons and glial cells via different mechanisms and has different effects on glutamate- and GABA-dependent synaptic transmission [52]. The multifaceted roles of ATP in the CNS support the notion that energy demand and synaptic function are intertwined. Therefore, any decline in mitochondrial ATP production can substantially and non-uniformly affect neuronal circuits.

Mitochondrial calcium buffering modulates synaptic calcium levels

Mitochondria possess an intricate molecular machinery that regulates calcium uptake and release. The molecular identification of the high-affinity (Kd < 2 nM) mitochondrial calcium uniporter (MCU) channel in 2011 [53–55] spurred research on mitochondrial calcium regulation. The MCU channel is inhibited at rest by regulatory proteins MICU1 and MICU2, and this inhibition is lifted under conditions of excess cytosolic calcium [56]. In humans, MICU1 mutations result in myopathy, learning deficits, and movement disorders [57]. MICU3, a less well-characterized regulatory protein of MCU, is exclusively expressed in the CNS [58], which suggests a specialized role for mitochondrial calcium in the nervous system. The calcium-buffering capacity of the mitochondrial matrix sink is maintained by releasing excess matrix calcium through the mitochondrial sodium– and proton–calcium exchangers and the low-conductance mode of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) [56,59]. An increase in mitochondrial calcium concentration is also closely tied to the tricarboxylic acid cycle and ATP synthesis [60]. This association can, therefore, indirectly affect synaptic calcium levels, because the calcium pumps localized on the endoplasmic reticulum and plasma membrane are ATP dependent. The 22q11DS mice have deficits in hippocampal short-term and long-term synaptic plasticities, which are the cellular correlates of learning and memory, and these deficits depend on mitochondrial calcium level [34] and Serca2 activity [30,32]. In a comprehensive GWAS, the ATP2A2 gene, which encodes SERCA2, was associated with schizophrenia [43], suggesting an interplay between the calcium-handling machinery in the mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum in the pathophysiology of the disease.

Mitochondrial redox regulation may contribute to the age dependence of 22q11DS phenotypes

Oxidative phosphorylation in mitochondria entails a series of electron-transfer reactions in the respiratory-chain complexes that eventually lead to the reduction of molecular oxygen to water [61]. These reactions are not foolproof and can result in electron leak, especially at complexes I and III, which gives rise to reactive oxygen species (ROS) [61]. Mitochondria have various antioxidants, such as superoxide dismutase-2, catalase, glutathione peroxidase, peroxiredoxins, and thioredoxins, to counteract ROS-induced damage [61,62]. Although multiple data sources have suggested that ROS are major contributors to the process of ageing, recent re-evaluation suggests that ROS are merely the mediators of age-dependent cellular damage [63,64]. Strikingly, some of the phenotypes associated with 22q11DS mice are also age dependent [31,33]. MicroRNA biogenesis may be the determinant of age dependence in these studies. Given the critical involvement of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in many synaptic functions, oxidation/reduction (redox) imbalance can also be a factor in age dependence of the 22q11DS phenotypes.

Mitochondrial lipid metabolism in synaptic vesicle recycling

Signal transduction at chemical synapses is mainly achieved by the release of synaptic vesicles containing neurotransmitters. Most attention has been focused on synaptic proteins and the need of ATP for synaptic vesicle recycling, but the rapid turnover of lipid membranes in the process has been underappreciated [65,66]. Although most phospholipids are synthesized in the endoplasmic reticulum, mitochondria-associated membranes (i.e., the contact sites between mitochondria and the endoplasmic reticulum) harbor enzymes involved in lipid biosynthesis [67–69]. Thus, further investigations are warranted to elucidate the role of mitochondria-associated membranes in the recycling of synaptic vesicles.

Mitochondrial trafficking may underlie the pathogenesis of neuropsychiatric diseases

Because of their polarity and varied architecture, neuronal cells face the challenge of distributing mitochondria throughout their dendritic arbor and the thin axonal branches over very long distances [70,71]. The relevance of mitochondrial trafficking to neuropsychiatric diseases is exemplified by the DISC1 (Disrupted in schizophrenia 1) gene. Mutations in DISC1 have been associated with several neuropsychiatric illnesses [72,73], and the putative underlying cause is alterations in the mitochondria–microtubule complex involved in intracellular trafficking [74,75]. DISC1 is also involved in dendritic morphogenesis [28]. The mitochondrial receptor Miro1, which mediates mitochondrial trafficking, has calcium-sensing EF-hand domains, suggesting that calcium signals that are crucial for synaptic plasticity also affect mitochondrial trafficking [70]. Neuronal mitochondrial trafficking is an active field of research, and we refer readers to other recent, more comprehensive reviews on this topic [70,71]. Other relevant mitochondrial events, such as mitochondrial fission and fusion, are also reviewed elsewhere [76,77]. The mitochondrial functions discussed thus far in this review apply to all cell types. However, some cell types (e.g., oligodendrocytes, interneurons, and astrocytes) have unique mitochondrial functions. This specialization indicates that these cell types in the CNS could be more vulnerable to some, but not other, mitochondrial deficits.

Mitochondria play a role in myelination by oligodendrocytes

The myelin sheath formed by oligodendrocytes is composed mainly of lipids. Mitochondria in oligodendrocytes are primarily located within the cytoplasmic ridges along the sheath and are characterized by reduced surface area of cristae, which suggests that ATP synthesis is not the primary function of these organelles in these cells [78]. Oligodendrocytes express metabotropic glutamatergic and purinergic receptors, which mediate calcium transient responses to the vesicular release of glutamate and ATP [79,80]. This form of extrasynaptic communication has been implicated in activity-dependent myelination [79,80]. An important ultrastructural alteration seen post-mortem in the brains of patients with schizophrenia is the paucity of mitochondria in oligodendrocytes. This finding suggests impaired connectivity in long-range neuronal connections [81,82]. Defective myelination is a common feature of many primary and secondary mitochondrial diseases [83], a fact that further supports the importance of mitochondria in myelination.

Mitochondrial function is crucial for the higher metabolic needs of interneurons

Multiple types of interneurons contribute to the complexity of neuronal circuit organization and function in the brain [84]. Parvalbumin-positive (PV) interneurons are particularly relevant to the this review, because these cells have higher numbers of mitochondria than other neuronal cell types and are enriched with cytochrome c, which is essential for oxidative phosphorylation [85]. PV interneurons are essential for setting the gamma frequencies observed in hippocampal–cortical networks [85]. The supercritical density of sodium channels in PV interneurons, which provides excellent conduction velocities in the specialized axonal arbor, comes at the expense of excess energy demand [85]. The Cox10 gene encodes cytochrome oxidase, which is the terminal enzyme in the electron transport chain. In PV neurons, deletion of Cox10 leads to abnormal gamma- and theta-frequency oscillations in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus of anaesthetized mice, thereby further supporting the notion that PV interneurons have a higher metabolic need than do most neurons [86]. An integrative analysis of various measures in post-mortem hippocampal samples from the Stanley Neuropathology Consortium found a decrease in PV interneuron density in the CA2 region [87]. Reduced feed-forward inhibition arising from decreased density of PV interneurons in the CA2 area underlies social-cognition deficits in the Df(16)A+/− mouse model of 22q11DS [88]. These findings highlight the pathophysiologic intersection between the higher metabolic needs of PV interneurons and the greater representation of mitochondrial genes in 22q11DS.

Mitochondrial ATP production may regulate glutamate uptake by astrocytes

A major function of astrocytes is to recycle the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate as inactive glutamine [89]. The astrocyte-localized, ATP-dependent enzyme glutamine synthetase serves this function [90,91] and demonstrates the unique need for mitochondrial ATP synthesis in astrocytes. Astrocytic uptake of glutamate is a secondary energy-dependent process [47,91]. The electrochemical gradient established by the sodium–potassium ATPase is used by glutamate transporters in astrocytes, hence glutamate transport indirectly depends on mitochondrial ATP production [47]. Glutamate uptake by astrocytes after neuronal activity immobilizes mitochondria in the perisynaptic processes, underlining the homeostatic need for mitochondrial localization in astrocytes [92].

Nuclear-encoded mitochondrial genes are implicated in the pathophysiology of 22q11DS

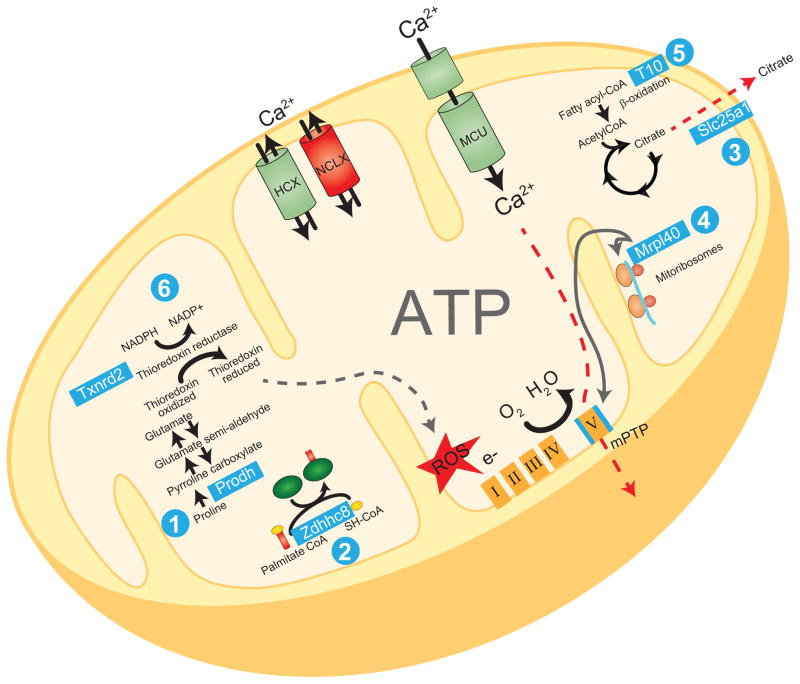

As mentioned earlier, six 22q11DS genes—Prodh, Slc25a1, Mrpl40, Zdhhc8, T10, and Txnrd2—are colocalized with mitochondria or implicated in mitochondrial function. Here we review recent data on these genes and their roles within mitochondria (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. 22q11DS genes encoding mitochondrial proteins and their functions.

(1) Prodh encodes mitochondrial proline dehydrogenase, which is involved in proline metabolism and is interconnected to glutamate synthesis. (2) Zdhhc8 encodes a protein that is involved in palmitoylation of proteins. (3) Slc25a1 encodes the mitochondrial citrate transporter, which mediates fatty acid metabolism. (4) Mrpl40 encodes one of the proteins in the mitochondrial large ribosomal subunit, which affects calcium extrusion via the permeability transition pore (mPTP). (5) T10 encodes a protein that is involved in fatty acid oxidation. (6) Txnrd2 encodes thioredoxin reductase 2, which maintains thioredoxin in a reduced state and contributes to oxidation/reduction (redox) regulation. HCX, hydrogen–calcium exchanger; MCU, mitochondrial calcium uniporter; NADPH and NADP+, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate; NCLX, sodium–calcium exchanger; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

Prodh

PRODH was one of the earliest genes implicated in 22q11DS pathophysiology [39]. The gene encodes proline dehydrogenase (also known as proline oxidase), which is involved in the catabolic conversion of proline to pyrroline-5 carboxylate (P5C) [93]. The P5C intermediary can be recycled to proline by P5C reductase or can be converted to glutamate by P5C dehydrogenase [93]. Extracellular proline at physiological concentrations can potentiate hippocampal NMDA (N-methyl-D-aspartate) glutamate receptors [94]. A recent report suggests that proline is a GABA mimetic that competes with intracellular GABA synthesis [95]. The metabolic relations among proline, glutamate, and GABA; the possibility of proline acting as a neurotransmitter; the high incidence of hyperprolinemia in patients with 22q11DS; and evidence of sensorimotor-gating deficits in Prodh-deficient mice all point to the importance of P5C in some aspects of 22q11DS pathophysiology [39,96,97]. However, the role of PRODH in schizophrenia is debatable [97].

Slc25a1

The Slc25a1 gene encodes a citrate transporter that catalyzes the efflux of citrate/isocitrate from the mitochondrial matrix in exchange for cytosolic malate [98]. Exported citrate molecules are converted to acetyl-coenzyme A, which is required for fatty acid synthesis [98]. Apart from serving as a source of citrate, which is needed for fatty acid synthesis, mitochondria provide the ATP required for the synthetic process [98]. Many Krebs’ cycle intermediates are altered in patients carrying mutations in SLC25A1, with symptoms manifesting as developmental delay, hypotonia, and seizures [99]. Imbalanced citrate metabolism often leads to the accumulation of 2-hydroxyglutarate. This can interfere with alpha-ketoglutarate uptake by astrocytes and lead to deficits in anaplerotic neurotransmitter synthesis. The importance of this gene in lipid biogenesis and the ATP dependence of the conversion might underlie the agenesis of the corpus callosum observed in a patient with SLC25A1 mutations [100].

Mrpl40

Mrpl40 encodes one of more than 50 proteins in the large ribosomal subunit of mitochondria [101]. Two elegant studies reporting the crystal structure of mammalian mitoribosomes identified the encoded protein mL40 at the P-finger of the large ribosomal subunit [102,103]. The function of this P-finger, which is unique to mammals, is yet to be determined [102,103]. Because of its ribosomal location, mL40 might be involved in some aspects of translation or posttranslational modification of nascent proteins. In a study of the association between nonsynonymous single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) and schizophrenia, MRPL40 was one of the top 25 candidates and was the only 22q11DS gene identified [104].

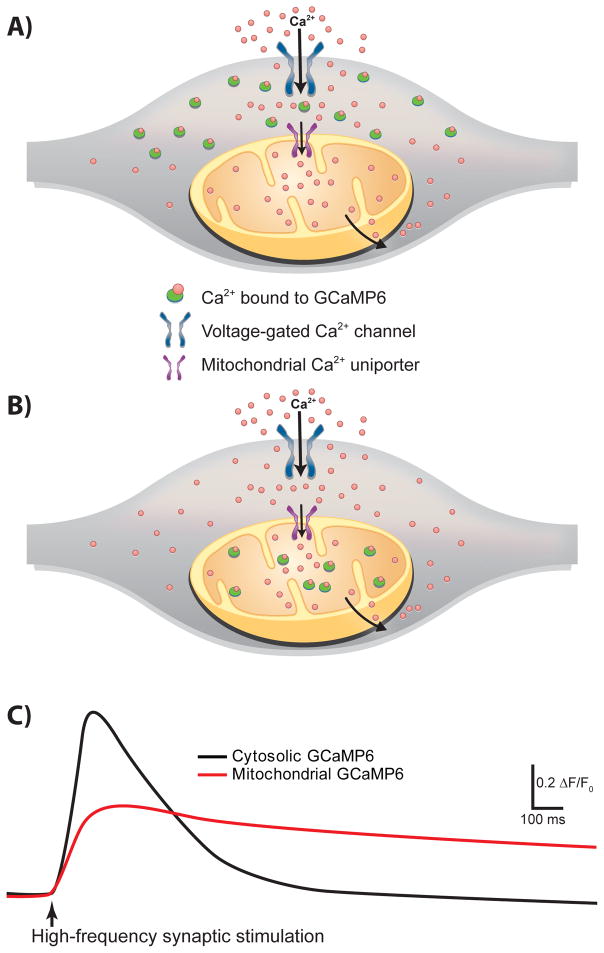

We identified Mrpl40 in our recent screening of genes that mediate short-term plasticity deficits in 22q11DS mice [34]. By using the ultrasensitive genetically encoded calcium indicator GCaMP6 [105] imaged in either the cytoplasm of presynaptic terminals or the presynaptic mitochondria (mitGCaMP6) (Fig. 4), we showed that haploinsufficiency of Mrpl40 affects the mPTP, resulting in abnormal mitochondrial calcium handling in presynaptic terminals of hippocampal neurons (Fig. 5). This in turn leads to abnormal short-term synaptic plasticity and working-memory deficit. To our knowledge, this is the first study that connects a nuclear-encoded mitochondrial protein, mitochondrial calcium, synaptic plasticity, and working memory. The GCaMP6 indicator enabled us to measure mitochondrial calcium uptake during ongoing synaptic activity and replicate mitochondrial calcium abnormalities observed in Mrpl40+/− mice by inhibiting adenine nucleotide translocases, which regulate the mPTP [34,106]. We also showed that increased activity of adenine nucleotide translocase 1 in presynaptic neurons rescues the synaptic plasticity deficit caused by Mrpl40 haploinsufficiency, and decreased activity of the enzyme mimics the deficit.

Figure 4. Measurements of activity-dependent calcium transients by using the ultrasensitive genetically encoded calcium indicator GCaMP6.

(A) Expression of GCaMP6 under the synapsin promoter enables the measurement of calcium levels in the neuronal cytosol/presynaptic terminal. (B) GCaMP6 targeted to mitochondria enables the measurement of mitochondrial calcium transients in isolation. (C) Mitochondrial calcium transients have a slower rise and much slower decay kinetics than do cytosolic transients in response to a train of stimulations delivered to axonal projections.

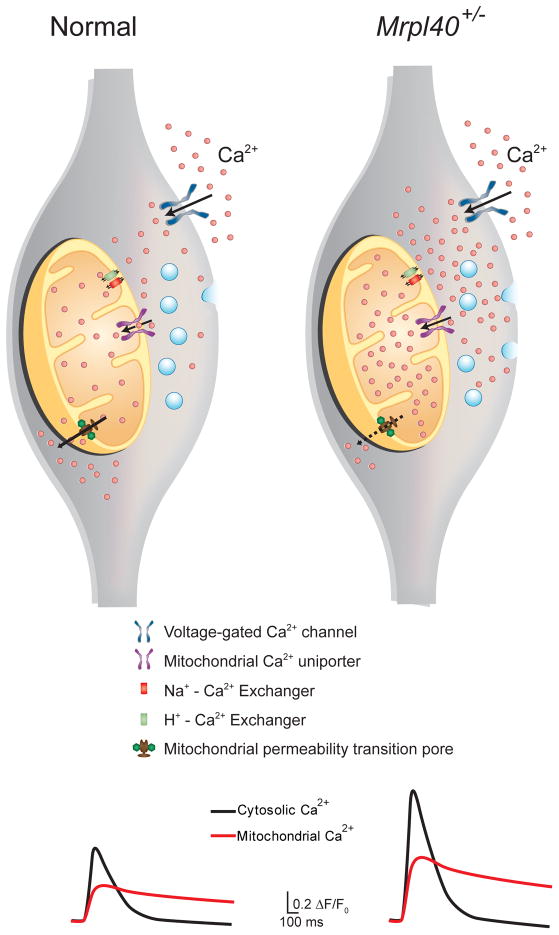

Figure 5. Mrpl40 haploinsufficiency leads to mPTP-dependent alterations in mitochondrial and presynaptic calcium handling.

(Left) In normal wild-type presynaptic terminals, the mitochondrial calcium-buffering capacity is aided by controlled influx through the mitochondrial uniporter complex (MUC), bidirectional fluxes through the sodium–calcium and proton–calcium exchangers (NCLX and HCLX, respectively), and slow extrusion of calcium through the low-conductance mode of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP). (Right) In Mrpl40-haploinsufficient terminals, slow extrusion of calcium via the mPTP is hindered, leading to calcium accumulation in the mitochondrial matrix. The resulting reduction in mitochondrial calcium-buffering capacity causes calcium build-up in the presynaptic cytosol, leading to increased release of synaptic vesicles. Traces at the bottom represent mitochondrial and cytosolic calcium transient currents in wild-type and Mrpl40+/− axon terminals measured using GCaMP6.

Unlike most studies that have implicated the mPTP in cell death, our experiments indicated that the mPTP has a more subtle role, such as affecting calcium levels in the presynaptic cytoplasm. This notion is consistent with a recent report suggesting that the mPTP acts in a physiologic low-conductance mode [59,107]. It remains to be determined how Mrpl40, a part of the mitochondrial ribosome, affects the mPTP. Progress in the field of mitochondrial translation and the development of novel tools to study post-translational modifications in mitochondria will help elucidate the molecular link between Mrpl40 and the mPTP. In contrast to the mPTP-dependent calcium-extrusion defect, which increases mitochondrial and cytosolic calcium levels, a defect in the MCU should increase cytosolic calcium levels but decrease mitochondrial calcium levels. Defects in either the MCU complex or the mPTP alter mitochondria–cytoplasm calcium exchange and eventually lead to increased neurotransmitter release. Two recent studies reporting mitochondrial calcium defects used different approaches to calculate the number of mitochondria localized to presynaptic terminals [34,108]. The first study addressing the role of Mrpl40 in short-term plasticity used three-dimensional electron microscopy in hippocampal sections [34], whereas the second study examining LKB1 kinase regulation of the MCU used a mitochondria-targeted fluorescent protein in primary neuronal cultures [108]. Both methods revealed that approximately 50% of presynaptic terminals have mitochondria, suggesting that presynaptic terminals are heterogeneous in energy demand and calcium regulation by mitochondria.

Zdhhc8

The Zdhhc8 gene encodes one of many palmitoyl transferases involved in S-palmitoylation, a process by which palmitoyl groups are added to certain proteins [109]. The palmitoyl code is used to sort proteins to specific subcellular compartments, and defects in that code can lead to various neuropsychiatric conditions [109]. ZDHHC8 was identified as a risk gene for schizophrenia in a high-density SNP analysis within the 22q11DS region [110], although this association was not found in studies of different populations [109]. A recent study showed that Zdhhc8 affects terminal axonal arborization, thereby affecting hippocampal–prefrontal connections and working memory [38]. Three pieces of complementary evidence support the localization of Zdhhc8 to the mitochondria: bioinformatics analysis to determine the mitochondrial localization signal, localization of the GFP-fusion protein, and colocalization with a mitochondrial marker [40]. However, an earlier study reported colocalization of Zdhhc8 with Golgi markers [110], raising some uncertainties about the specific subcellular localization of this protein.

T10

T10 is the mouse ortholog of the human TANGO2 (Transport and Golgi Organization 2) gene [40]. Mitochondrial localization of the encoded protein in mouse tissues has been confirmed using the same approaches used to identify Zdhhc8 localization [40]. However, studies in flies suggest that T10 is localized in the Golgi complex and cytosol, with a putative function in redistributing Golgi membranes to the endoplasmic reticulum [111] and raising questions about differences across species. Three unrelated individuals with biallelic truncating mutations in TANGO2 showed an infancy-onset metabolic disorder accompanied by encephalopathy and multiple organ disorder [112]. The metabolic signatures in these patients suggested defective mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation [112]. Fibroblast cell lines derived from the affected individuals revealed defective palmitate-dependent mitochondrial oxygen consumption and no gross difference in Golgi organization [112]. This result further supports a role for TANGO2 in mitochondrial beta-oxidation of fatty acids. However, the precise molecular mechanisms of TANGO2 and T10 remain unknown.

Txnrd2

The Txnrd2 gene encodes thioredoxin reductase 2 and plays a key role in redox signaling by maintaining thioredoxin in a reduced state [113]. Reduced thioredoxin is needed to scavenge the free radicals generated in excess from the mitochondrial electron transport chain [113]. Txnrd2 has been implicated in ageing and some heart diseases [114]. Of the several antioxidant systems (e.g., thioredoxin-2, glutathione, and catalase), the thioredoxin-2 system catalyzes approximately 60% ± 20% of the ROS detoxification in rat brain mitochondria [115]. Inhibition of thioredoxin-2 by 1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene in hippocampal slice cultures revealed that interneurons and microglial cells are the most prone to ROS toxicity [115].

Other 22q11DS genes

In addition to the genes that encode mitochondrial proteins, other genes in the 22q11 region might indirectly affect mitochondrial function. For example, Dgcr8, which is involved in microRNA processing, may affect mitochondrial calcium buffering, because miR-25 overexpression reduces MCU activity [116]. Dgcr8-dependent depletion of miR-25 and miR-185 also affects SERCA2 [32,33], which depends on mitochondrial ATP for its function.

Mitochondrial heteroplasmy can lead to incomplete penetrance of neuropsychiatric phenotypes

The number of copies of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) in a single cell varies from 100 to 1000, depending on the cell type [117]. The mtDNA is degraded and replicated, even in postmitotic cells [117]. This feature gives rise to a situation wherein a proportion of mtDNA carries mutations that cause heteroplasmy [117]. Inherited mtDNA heteroplasmy manifests as pathology when it reaches a critical threshold, usually during the prenatal stage of development [118,119]. Even in healthy individuals, the proportion of mutant mtDNA accumulation increases with age [117]. Although these mutations might not reach a pathogenic threshold by themselves, they can be pathogenic when combined with nuclear DNA mutations. The additive effect of nuclear DNA and mtDNA mutations, in turn, may depend on the level of heteroplasmy achieved and the criticality of the gene product for mitochondrial function. The mtDNA heteroplasmy acquired by postmitotic cells over their lifespan most likely contributes to the incomplete penetrance and late onset of neuropsychiatric conditions in patients with 22q11DS. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that the penetrance of all 22q11DS symptoms is incomplete, and even monozygotic twins with 22q11DS exhibit phenotypic discordance [120].

Conclusions and outlook

In this review, we have discussed several roles of mitochondria that impinge on the integrity of synaptic function and how different cell types vary in their mitochondrial needs. We highlighted how the 22q11DS mitochondrial genes can affect different aspects of mitochondrial function and took a glimpse at some recent evidence supporting the involvement of these genes in neuropsychiatric etiopathogenesis. We have also speculated on how mitochondrial defects contribute to the age dependence and incomplete penetrance of neuropsychiatric phenotypes. We propose that defects in nuclear-encoded mitochondrial proteins do not uniformly affect all neural circuits, because the circuits have heterogeneous demands. For example, compared with some unmyelinated circuits, myelinated long-range connections will be more vulnerable to defective mitochondrial fatty acid metabolism.

The idea that mitochondrial deficits give rise to complex psychiatric diseases instead of whole organismal pathology is implicit. The challenge in delineating these subtleties lies in integrating the various in vitro tools for studying mitochondria into the context of neural circuits, which are usually studied in rodent brain slices or in vivo. An amenable approach is to transition to relevant cellular models after the neural circuit underpinnings have been identified. Once a firm mechanistic link is established using cellular and brain slice models, unique features of the mitochondrial subcellular compartment can be used to target therapeutics with subcellular precision. Meanwhile, mouse models of 22q11DS, with their well-established relevance to neuropsychiatric diseases, serve as a springboard to connect various dots, such as nuclear genes encoding mitochondrial proteins, the mitochondrial functional deficit caused by their mutation, neural circuit dysfunction, and the spectrum of behavioral alterations.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants R01 MH095810 and R01 MH097742, NARSAD Independent Investigator Grant, and ALSAC (S.S.Z.). We thank Vani Shanker and Angela McArthur for editing the manuscript and Ashley Broussard and Jerry Harris for help with the artwork.

Abbreviation list

- 22q11DS

22q11.2 deletion syndrome

- ATP

Adenosine triphosphate

- CNS

Central nervous system

- GABA

Gamma-amino butyric acid

- GCaMP6

Genetically encoded ultrasensitive calcium indicator

- GWAS

Genome-wide association study

- HCX

H+-Ca2+ exchanger

- MCU

Mitochondrial calcium uniporter

- mitGCaMP6

GCaMP6 targeted to mitochondria

- mPTP

Mitochondrial permeability transition pore

- mtDNA

Mitochondrial DNA

- NMDA

N-methyl-D-aspartate

- NADPH and NADP

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate

- NCLX

Na+-Ca2+ exchanger

- P5C

Pyrroline-5 carboxylate

- PV

Parvalbumin

- redox

Oxidation/reduction

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- SERCA2

(Sarco)endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2

- SNP

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- vATPase

Vesicular ATPase

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.SAMHSA. Behavioral health trends in the United States: results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2015. (HHS Publication No. SMA 15-4927, NSDUH Series H-50) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray CJL, Vos T, Lozano R, Naghavi M, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet. 2012;380:2197–223. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roehrig C. Mental Disorders Top The List Of The Most Costly Conditions In The United States: $201 Billion. Health Affairs. 2016;35:1130–5. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nestler EJ, Hyman SE. Animal models of neuropsychiatric disorders. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:1161–9. doi: 10.1038/nn.2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindsay EA, Botta A, Jurecic V, Carattini-Rivera S, et al. Congenital heart disease in mice deficient for the DiGeorge syndrome region. Nature. 1999;401:379–83. doi: 10.1038/43900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stark KL, Xu B, Bagchi A, Lai WS, et al. Altered brain microRNA biogenesis contributes to phenotypic deficits in a 22q11-deletion mouse model. Nat Genet. 2008;40:751–60. doi: 10.1038/ng.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Merscher S, Funke B, Epstein JA, Heyer J, et al. TBX1 is responsible for cardiovascular defects in velo-cardio-facial/DiGeorge syndrome. Cell. 2001;104:619–29. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00247-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bassett AS, McDonald-McGinn DM, Devriendt K, Digilio MC, et al. Practical guidelines for managing patients with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. The Journal of pediatrics. 2011;159:332–9. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.02.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaminsky EB, Kaul V, Paschall J, Church DM, et al. An evidence-based approach to establish the functional and clinical significance of copy number variants in intellectual and developmental disabilities. Genetics in medicine: official journal of the American College of Medical Genetics. 2011;13:777–84. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31822c79f9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McDonald-McGinn DM, Sullivan KE. Chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (DiGeorge syndrome/velocardiofacial syndrome) Medicine (Baltimore) 2011;90:1–18. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e3182060469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scambler PJ. The 22q11 deletion syndromes. Human Molecular Genetics. 2000;9:2421–6. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.16.2421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pulver AE. Search for schizophrenia susceptibility genes. Biological psychiatry. 2000;47:221–30. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00281-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chow EW, Watson M, Young DA, Bassett AS. Neurocognitive profile in 22q11 deletion syndrome and schizophrenia. Schizophrenia research. 2006;87:270–8. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fung WL, McEvilly R, Fong J, Silversides C, et al. Elevated prevalence of generalized anxiety disorder in adults with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. The American journal of psychiatry. 2010;167:998. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09101463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gothelf D, Frisch A, Munitz H, Rockah R, et al. Clinical characteristics of schizophrenia associated with velo-cardio-facial syndrome. Schizophrenia research. 1999;35:105–12. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(98)00114-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Green T, Gothelf D, Glaser B, Debbane M, et al. Psychiatric disorders and intellectual functioning throughout development in velocardiofacial (22q11.2 deletion) syndrome. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48:1060–8. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181b76683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murphy KC, Jones LA, Owen MJ. High rates of schizophrenia in adults with velo-cardio-facial syndrome. Archives of general psychiatry. 1999;56:940–5. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.10.940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pulver AE, Nestadt G, Goldberg R, Shprintzen RJ, et al. Psychotic illness in patients diagnosed with velo-cardio-facial syndrome and their relatives. The Journal of nervous and mental disease. 1994;182:476–8. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199408000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bassett AS, Chow EW, Weksberg R. Chromosomal abnormalities and schizophrenia. American journal of medical genetics. 2000;97:45–51. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(200021)97:1<45::aid-ajmg6>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murphy KC. Schizophrenia and velo-cardio-facial syndrome. Lancet. 2002;359:426–30. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07604-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feinstein C, Eliez S, Blasey C, Reiss AL. Psychiatric disorders and behavioral problems in children with velocardiofacial syndrome: usefulness as phenotypic indicators of schizophrenia risk. Biological psychiatry. 2002;51:312–8. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01231-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bassett AS, Chow EW, Husted J, Weksberg R, et al. Clinical features of 78 adults with 22q11 Deletion Syndrome. American journal of medical genetics Part A. 2005;138:307–13. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vorstman JA, Breetvelt EJ, Thode KI, Chow EW, et al. Expression of autism spectrum and schizophrenia in patients with a 22q11.2 deletion. Schizophrenia research. 2013;143:55–9. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shprintzen RJ, Goldberg R, Golding-Kushner KJ, Marion RW. Late-onset psychosis in the velo-cardio-facial syndrome. American journal of medical genetics. 1992;42:141–2. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320420131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schneider M, Debbane M, Bassett AS, Chow EW, et al. Psychiatric disorders from childhood to adulthood in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome: results from the International Consortium on Brain and Behavior in 22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome. The American journal of psychiatry. 2014;171:627–39. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13070864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bassett AS, Chow EW, AbdelMalik P, Gheorghiu M, et al. The schizophrenia phenotype in 22q11 deletion syndrome. The American journal of psychiatry. 2003;160:1580–6. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.9.1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jonas RK, Montojo CA, Bearden CE. The 22q11.2 deletion syndrome as a window into complex neuropsychiatric disorders over the lifespan. Biological psychiatry. 2014;75:351–60. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Norkett R, Modi S, Birsa N, Atkin TA, et al. DISC1-dependent Regulation of Mitochondrial Dynamics Controls the Morphogenesis of Complex Neuronal Dendrites. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2016;291:613–29. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.699447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paylor R, Lindsay E. Mouse Models of 22q11 Deletion Syndrome. Biological psychiatry. 2006;59:1172–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Earls LR, Zakharenko SS. A Synaptic Function Approach to Investigating Complex Psychiatric Diseases. The Neuroscientist. 2014;20:257–71. doi: 10.1177/1073858413498307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chun S, Westmoreland JJ, Bayazitov IT, Eddins D, et al. Specific disruption of thalamic inputs to the auditory cortex in schizophrenia models. Science. 2014;344:1178–82. doi: 10.1126/science.1253895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Earls LR, Bayazitov IT, Fricke RG, Berry RB, et al. Dysregulation of Presynaptic Calcium and Synaptic Plasticity in a Mouse Model of 22q11 Deletion Syndrome. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30:15843–55. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1425-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Earls LR, Fricke RG, Yu J, Berry RB, et al. Age-Dependent MicroRNA Control of Synaptic Plasticity in 22q11 Deletion Syndrome and Schizophrenia. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2012;32:14132–44. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1312-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Devaraju P, Yu J, Eddins D, Mellado-Lagarde MM, et al. Haploinsufficiency of the 22q11.2 microdeletion gene Mrpl40 disrupts short-term synaptic plasticity and working memory through dysregulation of mitochondrial calcium. Molecular psychiatry. 2016 doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sigurdsson T, Stark KL, Karayiorgou M, Gogos JA, et al. Impaired hippocampal-prefrontal synchrony in a genetic mouse model of schizophrenia. Nature. 2010;464:763–7. doi: 10.1038/nature08855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wong LM, Riggins T, Harvey D, Cabaral M, et al. Children with chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome exhibit impaired spatial working memory. American journal on intellectual and developmental disabilities. 2014;119:115–32. doi: 10.1352/1944-7558-119.2.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bearden CE, Woodin MF, Wang PP, Moss E, et al. The neurocognitive phenotype of the 22q11.2 deletion syndrome: selective deficit in visual-spatial memory. Journal of clinical and experimental neuropsychology. 2001;23:447–64. doi: 10.1076/jcen.23.4.447.1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mukai J, Tamura M, Fénelon K, Rosen Andrew M, et al. Molecular Substrates of Altered Axonal Growth and Brain Connectivity in a Mouse Model of Schizophrenia. Neuron. 2015;86:680–95. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gogos J, Santha M, Takacs Z, Beck KD, et al. The gene encoding proline dehydrogenase modulates sensorimotor gating in mice. Nat Genet. 1999;21:434–9. doi: 10.1038/7777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maynard TM, Meechan DW, Dudevoir ML, Gopalakrishna D, et al. Mitochondrial localization and function of a subset of 22q11 deletion syndrome candidate genes. Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience. 2008;39:439–51. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2008.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hjelm BE, Rollins B, Mamdani F, Lauterborn JC, et al. Evidence of Mitochondrial Dysfunction within the Complex Genetic Etiology of Schizophrenia. Molecular Neuropsychiatry. 2015;1:201–19. doi: 10.1159/000441252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ripke S, O’Dushlaine C, Chambert K, Moran JL, et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies 13 new risk loci for schizophrenia. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1150–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.2742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics C. Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature. 2014;511:421–7. doi: 10.1038/nature13595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wesseling H, Xu B, Want EJ, Holmes E, et al. System-based proteomic and metabonomic analysis of the Df(16)A+/− mouse identifies potential miR–185 targets and molecular pathway alterations. Mol Psychiatry. 2016 doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Manji H, Kato T, Di Prospero NA, Ness S, et al. Impaired mitochondrial function in psychiatric disorders. Nature reviews Neuroscience. 2012;13:293–307. doi: 10.1038/nrn3229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marin SE, Saneto RP. Neuropsychiatric Features in Primary Mitochondrial Disease. Neurologic Clinics. 2016;34:247–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2015.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harris Julia J, Jolivet R, Attwell D. Synaptic Energy Use and Supply. Neuron. 2012;75:762–77. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rangaraju V, Calloway N, Ryan Timothy A. Activity-Driven Local ATP Synthesis Is Required for Synaptic Function. Cell. 2014;156:825–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marshansky V, Futai M, Grüber G. Eukaryotic V-ATPase and Its Super-complexes: From Structure and Function to Disease and Drug Targeting. In: Chakraborti S, editor. Regulation of Ca2+-ATPases,V-ATPases and F-ATPases. Springer; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Farsi Z, Preobraschenski J, van den Bogaart G, Riedel D, et al. Single-vesicle imaging reveals different transport mechanisms between glutamatergic and GABAergic vesicles. Science. 2016;351:981–4. doi: 10.1126/science.aad8142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Burnstock G. An introduction to the roles of purinergic signalling in neurodegeneration, neuroprotection and neuroregeneration. Neuropharmacology. 2016;104:4–17. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dunwiddie TV, Masino SA. The role and regulation of adenosine in the central nervous system. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:31–55. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Baughman JM, Perocchi F, Girgis HS, Plovanich M, et al. Integrative genomics identifies MCU as an essential component of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Nature. 2011;476:341–5. doi: 10.1038/nature10234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.De Stefani D, Raffaello A, Teardo E, Szabo I, et al. A forty-kilodalton protein of the inner membrane is the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Nature. 2011;476:336–40. doi: 10.1038/nature10230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kirichok Y, Krapivinsky G, Clapham DE. The mitochondrial calcium uniporter is a highly selective ion channel. Nature. 2004;427:360–4. doi: 10.1038/nature02246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kamer KJ, Mootha VK. The molecular era of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2015;16:545–53. doi: 10.1038/nrm4039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Logan CV, Szabadkai G, Sharpe JA, Parry DA, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in MICU1 cause a brain and muscle disorder linked to primary alterations in mitochondrial calcium signaling. Nat Genet. 2014;46:188–93. doi: 10.1038/ng.2851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Plovanich M, Bogorad RL, Sancak Y, Kamer KJ, et al. MICU2, a Paralog of MICU1, Resides within the Mitochondrial Uniporter Complex to Regulate Calcium Handling. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e55785. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bernardi P, von Stockum S. The permeability transition pore as a Ca2+ release channel: New answers to an old question. Cell Calcium. 2012;52:22–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2012.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rizzuto R, De Stefani D, Raffaello A, Mammucari C. Mitochondria as sensors and regulators of calcium signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:566–78. doi: 10.1038/nrm3412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zorov DB, Juhaszova M, Sollott SJ. Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and ROS-Induced ROS Release. Physiological Reviews. 2014;94:909–50. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00026.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Andreyev AY, Kushnareva YE, Murphy AN, Starkov AA. Mitochondrial ROS metabolism: 10 Years later. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2015;80:517–31. doi: 10.1134/S0006297915050028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.López-Otín C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M, et al. The Hallmarks of Aging. Cell. 2013;153:1194–217. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hekimi S, Lapointe J, Wen Y. Taking a “good” look at free radicals in the aging process. Trends in Cell Biology. 2011;21:569–76. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rohrbough J, Broadie K. Lipid regulation of the synaptic vesicle cycle. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:139–50. doi: 10.1038/nrn1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Puchkov D, Haucke V. Greasing the synaptic vesicle cycle by membrane lipids. Trends in Cell Biology. 2013;23:493–503. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stone SJ, Levin MC, Zhou P, Han J, et al. The Endoplasmic Reticulum Enzyme DGAT2 Is Found in Mitochondria-associated Membranes and Has a Mitochondrial Targeting Signal That Promotes Its Association with Mitochondria. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2009;284:5352–61. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805768200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stone SJ, Vance JE. Phosphatidylserine Synthase-1 and -2 Are Localized to Mitochondria-associated Membranes. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275:34534–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002865200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vance JE. MAM (mitochondria-associated membranes) in mammalian cells: Lipids and beyond. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids. 2014;1841:595–609. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2013.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sheng Z-H. Mitochondrial trafficking and anchoring in neurons: New insight and implications. The Journal of Cell Biology. 2014;204:1087–98. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201312123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schwarz TL. Mitochondrial Trafficking in Neurons. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 2013;5 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a011304. pii: a011304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chubb JE, Bradshaw NJ, Soares DC, Porteous DJ, et al. The DISC locus in psychiatric illness. Mol Psychiatry. 2007;13:36–64. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Porteous DJ, Millar JK, Brandon NJ, Sawa A. DISC1 at 10: connecting psychiatric genetics and neuroscience. Trends in Molecular Medicine. 2011;17:699–706. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Atkin TA, MacAskill AF, Brandon NJ, Kittler JT. Disrupted in Schizophrenia-1 regulates intracellular trafficking of mitochondria in neurons. Molecular psychiatry. 2011;16:122–4. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ogawa F, Malavasi ELV, Crummie DK, Eykelenboom JE, et al. DISC1 complexes with TRAK1 and Miro1 to modulate anterograde axonal mitochondrial trafficking. Human Molecular Genetics. 2014;23:906–19. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mishra P, Chan DC. Metabolic regulation of mitochondrial dynamics. The Journal of Cell Biology. 2016;212:379–87. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201511036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pernas L, Scorrano L. Mito-Morphosis: Mitochondrial Fusion, Fission, and Cristae Remodeling as Key Mediators of Cellular Function. Annual Review of Physiology. 2015;78:505–31. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021115-105011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rinholm JE, Vervaeke K, Tadross MR, Tkachuk AN, et al. Movement and structure of mitochondria in oligodendrocytes and their myelin sheaths. Glia. 2016;64:810–25. doi: 10.1002/glia.22965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wake H, Lee PR, Fields RD. Control of Local Protein Synthesis and Initial Events in Myelination by Action Potentials. Science. 2011;333:1647–51. doi: 10.1126/science.1206998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wake H, Ortiz FC, Woo DH, Lee PR, et al. Nonsynaptic junctions on myelinating glia promote preferential myelination of electrically active axons. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7844. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Uranova NA, Vikhreva OV, Rachmanova VI, Orlovskaya DD. Ultrastructural Alterations of Myelinated Fibers and Oligodendrocytes in the Prefrontal Cortex in Schizophrenia: A Postmortem Morphometric Study. Schizophrenia Research and Treatment. 2011;2011:325789. doi: 10.1155/2011/325789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Vostrikov V, Uranova N. Age-Related Increase in the Number of Oligodendrocytes Is Dysregulated in Schizophrenia and Mood Disorders. Schizophrenia Research and Treatment. 2011;2011:174689. doi: 10.1155/2011/174689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Morato L, Bertini E, Verrigni D, Ardissone A, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in central nervous system white matter disorders. Glia. 2014;62:1878–94. doi: 10.1002/glia.22670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Roux L, Buzsáki G. Tasks for inhibitory interneurons in intact brain circuits. Neuropharmacology. 2015;88:10–23. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kann O. The interneuron energy hypothesis: Implications for brain disease. Neurobiology of Disease. 2016;90:75–85. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2015.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Inan M, Zhao M, Manuszak M, Karakaya C, et al. Energy deficit in parvalbumin neurons leads to circuit dysfunction, impaired sensory gating and social disability. Neurobiology of Disease. 2016;93:35–46. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2016.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Knable MB, Barci BM, Webster MJ, Meador-Woodruff J, et al. Molecular abnormalities of the hippocampus in severe psychiatric illness: postmortem findings from the Stanley Neuropathology Consortium. Mol Psychiatry. 2004;9:609–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Piskorowski R, Nasrallah K, Diamantopoulou A, Mukai J, et al. Age-Dependent Specific Changes in Area CA2 of the Hippocampus and Social Memory Deficit in a Mouse Model of the 22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome. Neuron. 2016;89:163–76. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.11.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bak LK, Schousboe A, Waagepetersen HS. The glutamate/GABA-glutamine cycle: aspects of transport, neurotransmitter homeostasis and ammonia transfer. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2006;98:641–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Martinez-Hernandez A, Bell K, Norenberg M. Glutamine synthetase: glial localization in brain. Science. 1977;195:1356–8. doi: 10.1126/science.14400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Danbolt NC, Furness DN, Zhou Y. Neuronal vs glial glutamate uptake: Resolving the conundrum. Neurochemistry International. 2016;98:29–45. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2016.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Jackson JG, O’Donnell JC, Takano H, Coulter DA, et al. Neuronal Activity and Glutamate Uptake Decrease Mitochondrial Mobility in Astrocytes and Position Mitochondria Near Glutamate Transporters. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2014;34:1613–24. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3510-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hu C-aA, Phang JM, Valle D. Proline metabolism in health and disease. Amino Acids. 2008;35:651–2. doi: 10.1007/s00726-008-0102-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Cohen SM, Nadler JV. Proline-induced potentiation of glutamate transmission. Brain Res. 1997;761:271–82. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00352-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Crabtree GW, Park AJ, Gordon JA, Gogos JA. Cytosolic Accumulation of L-Proline Disrupts GABA-Ergic Transmission through GAD Blockade. Cell reports. 2016;17:570–82. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Jacquet H, Demily C, Houy E, Hecketsweiler B, et al. Hyperprolinemia is a risk factor for schizoaffective disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2004;10:479–85. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Willis A, Bender HU, Steel G, Valle D. PRODH variants and risk for schizophrenia. Amino Acids. 2008;35:673–9. doi: 10.1007/s00726-008-0111-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Palmieri F. The mitochondrial transporter family SLC25: Identification, properties and physiopathology. Molecular Aspects of Medicine. 2013;34:465–84. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Napoli E, Tassone F, Wong S, Angkustsiri K, et al. Mitochondrial Citrate Transporter-dependent Metabolic Signature in the 22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2015;290:23240–53. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.672360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Edvardson S, Porcelli V, Jalas C, Soiferman D, et al. Agenesis of corpus callosum and optic nerve hypoplasia due to mutations in SLC25A1 encoding the mitochondrial citrate transporter. Journal of Medical Genetics. 2013;50:240–5. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-101485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.O’Brien TW. Evolution of a protein-rich mitochondrial ribosome: implications for human genetic disease. Gene. 2002;286:73–9. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00808-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Greber BJ, Boehringer D, Leibundgut M, Bieri P, et al. The complete structure of the large subunit of the mammalian mitochondrial ribosome. Nature. 2014;515:283–6. doi: 10.1038/nature13895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Greber BJ, Boehringer D, Leitner A, Bieri P, et al. Architecture of the large subunit of the mammalian mitochondrial ribosome. Nature. 2014;505:515–9. doi: 10.1038/nature12890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Carrera N, Arrojo M, Sanjuán J, Ramos-Ríos Rn, et al. Association Study of Nonsynonymous Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms in Schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry. 2012;71:169–77. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Chen TW, Wardill TJ, Sun Y, Pulver SR, et al. Ultrasensitive fluorescent proteins for imaging neuronal activity. Nature. 2013;499:295–300. doi: 10.1038/nature12354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kwong Jennifer Q, Molkentin Jeffery D. Physiological and Pathological Roles of the Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore in the Heart. Cell Metabolism. 2015;21:206–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Barsukova A, Komarov A, Hajnóczky G, Bernardi P, et al. Activation of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore modulates Ca2+ responses to physiological stimuli in adult neurons. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;33:831–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07576.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kwon SK, Sando R, 3rd, Lewis TL, Hirabayashi Y, et al. LKB1 Regulates Mitochondria-Dependent Presynaptic Calcium Clearance and Neurotransmitter Release Properties at Excitatory Synapses along Cortical Axons. PLoS biology. 2016;14:e1002516. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Hornemann T. Palmitoylation and depalmitoylation defects. Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease. 2015;38:179–86. doi: 10.1007/s10545-014-9753-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Mukai J, Liu H, Burt RA, Swor DE, et al. Evidence that the gene encoding ZDHHC8 contributes to the risk of schizophrenia. Nat Genet. 2004;36:725–31. doi: 10.1038/ng1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Bard F, Casano L, Mallabiabarrena A, Wallace E, et al. Functional genomics reveals genes involved in protein secretion and Golgi organization. Nature. 2006;439:604–7. doi: 10.1038/nature04377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kremer Laura S, Distelmaier F, Alhaddad B, Hempel M, et al. Bi-allelic Truncating Mutations in TANGO2 Cause Infancy-Onset Recurrent Metabolic Crises with Encephalocardiomyopathy. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 2016;98:358–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Mustacich D, Powis G. Thioredoxin reductase. Biochemical Journal. 2000;346:1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kiermayer C, Northrup E, Schrewe A, Walch A, et al. Heart-specific knockout of the mitochondrial thioredoxin reductase (Txnrd2) induces metabolic and contractile dysfunction in the aging myocardium. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2015;4 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002153. pii: e002153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Kudin AP, Augustynek B, Lehmann AK, Kovács R, et al. The contribution of thioredoxin-2 reductase and glutathione peroxidase to H2O2 detoxification of rat brain mitochondria. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics. 2012;1817:1901–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Marchi S, Lupini L, Patergnani S, Rimessi A, et al. Downregulation of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter by cancer-related miR-25. Curr Biol. 2013;23:58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Stewart JB, Chinnery PF. The dynamics of mitochondrial DNA heteroplasmy: implications for human health and disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2015;16:530–42. doi: 10.1038/nrg3966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Wai T, Teoli D, Shoubridge EA. The mitochondrial DNA genetic bottleneck results from replication of a subpopulation of genomes. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1484–8. doi: 10.1038/ng.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Cao L, Shitara H, Horii T, Nagao Y, et al. The mitochondrial bottleneck occurs without reduction of mtDNA content in female mouse germ cells. Nat Genet. 2007;39:386–90. doi: 10.1038/ng1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Singh SM, Murphy B, O’Reilly R. Monozygotic twins with chromosome 22q11 deletion and discordant phenotypes: updates with an epigenetic hypothesis. Journal of Medical Genetics. 2002;39:e71. doi: 10.1136/jmg.39.11.e71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]