Abstract

Haptoglobin (Hp) binds hemoglobin (Hb) with high affinity and provides the primary defense against its toxicity after intravascular hemolysis. Neurons are exposed to extracellular Hb after CNS hemorrhage, and a therapeutic effect of Hp via Hb sequestration has been hypothesized. In the present study, we tested the hypothesis that Hp protects neurons from Hb in primary mixed cortical cell cultures. Treatment with low micromolar concentrations of human Hb for 24 hours resulted in loss of 10–20% of neurons without injuring glia. Concomitant treatment with Hp surprisingly increased neuronal loss five-sevenfold, with similar results produced by Hp 1-1 and 2-2 phenotypes. Consistent with a recent in vivo observation, neurons expressed the CD163 receptor for Hb and the Hb-Hp complex in these cultures. Hp reduced overall Hb uptake, directed it away from the astrocyte-rich CD163-negative glial monolayer, and decreased induction of the iron-binding protein ferritin. Hb-Hp complex neuronal toxicity, like that of Hb per se, was iron-dependent and reduced by deferoxamine and 2,2’ bipyridyl. These results suggest that Hp increases the vulnerability of CD163+ neurons to Hb by permitting Hb uptake while attenuating the protective response of ferritin induction by glial cells.

Keywords: Intracerebral hemorrhage, Iron, Neurotoxicity, Stroke, Subarachnoid hemorrhage

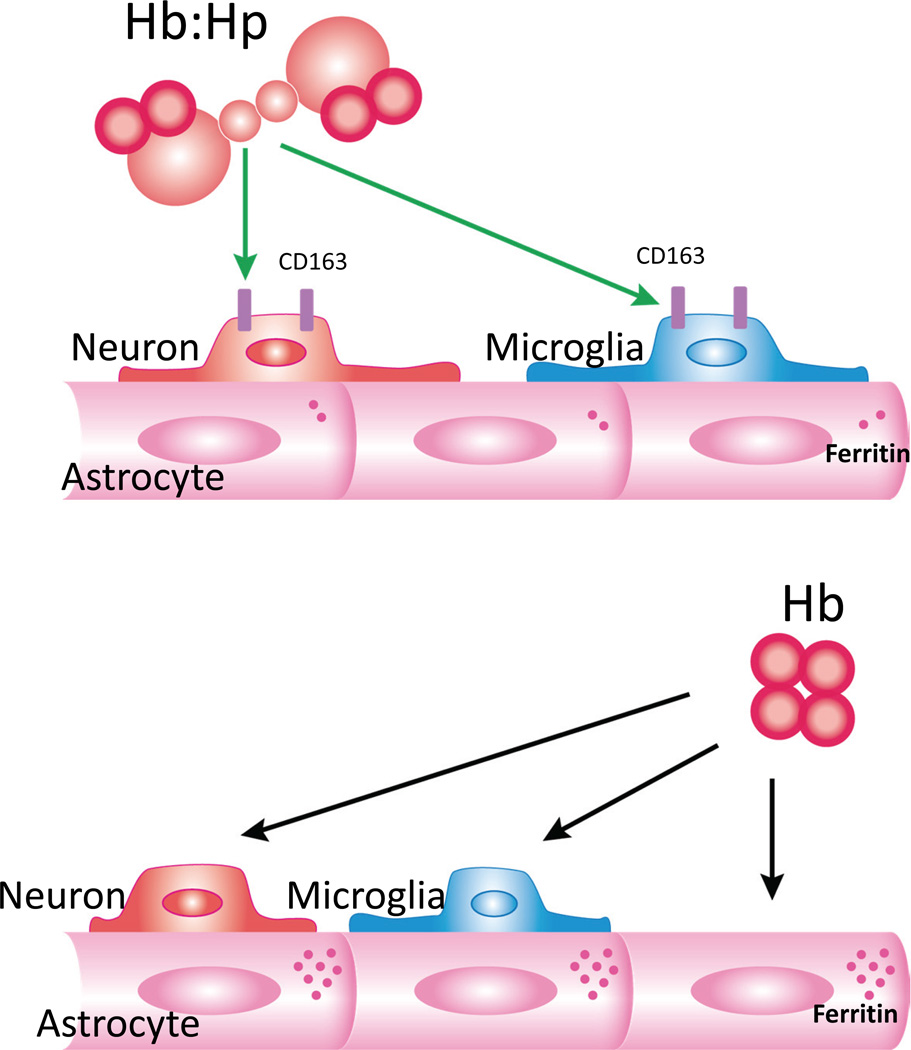

Graphical abstract

Binding of hemoglobin to haptoglobin directs Hb to CD163+ neurons and microglia and away from astrocytes. This decreases expression of ferritin by astrocytes and increases neuronal injury.

Introduction

Hemoglobin (Hb) is by far the most abundant erythrocyte protein, with a concentration of 2–2.7 mM in whole blood. In the immediate aftermath of an intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), its sequestration within erythrocytes mitigates its impact on adjacent cells. Unfortunately, erythrocyte lysis begins within 24 hours of ictus and may continue for weeks, exposing cells adjacent to the clot to its pro-oxidant effects (Wu et al. 2003). The neuronal toxicity of Hb and its degradation products was first characterized in vitro and was supported by observations in rodent ICH models (Regan & Panter 1993, Xi et al. 1998). These studies have led to the hypothesis that Hb initiates delayed injury cascades that can be mitigated by specific pharmacotherapies (Huang et al. 2002).

The primary line of defense against free Hb in plasma is provided by haptoglobin (Hp), which binds it with very high affinity (Kd ~ 10−15M) and transports it to the liver for CD163 receptor-mediated endocytosis, catabolism and iron recycling (Lim et al. 2001). It has long been assumed that Hp also neutralizes the pro-oxidant effect of Hb in the CNS, and that cells are at risk only when its binding sites are saturated (Sadrzadeh et al. 1984, Panter et al. 1985). Consistent with this hypothesis, Hp knockout increased perihematomal injury and worsened neurological outcome in a rodent ICH model, while exogenous Hp attenuated Hb toxicity in pure neuronal cultures (Zhao et al. 2009). The beneficial effect of Hp after hemorrhagic stroke, however, may not be limited to or even mediated by Hb scavenging, since the Hb-Hp complex downregulates the inflammatory response and polarizes macrophages towards a reparative phenotype (Kaempfer et al. 2011)

Potentially deleterious effects of Hp after CNS hemorrhage have received little consideration. Although the CD163 receptor scavenges both Hb and Hb-Hp complexes, the latter has greater binding affinity and is taken up more rapidly by CD163-expressing microglia and infiltrating macrophages (Schaer et al. 2006b, Etzerodt et al. 2013). These cell populations are equipped for heme catabolism and iron storage due to heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) and ferritin expression, but they also export excess iron via ferroportin (Ganz 2012). Extracellular iron is particularly problematic in the CNS due to the minimal iron binding capacity of its interstitial fluid (Moos et al. 2007). Furthermore, in an oxidative environment, Hb-Hp complexes undergo covalent crosslinking, increasing their uptake by macrophages and generating superoxide (Kapralov et al. 2009). Recent evidence suggests that Hp may also increase neuronal Hb uptake after hemorrhagic stroke. Garton et al. have reported that hippocampal neurons express CD163 after neonatal intraventricular hemorrhage (Garton et al. 2016), consistent with a prior report of neuronal uptake of Hb in vitro (Lara et al. 2009). Neurons are capable of heme degradation due to robust expression of HO-2, the constitutive isoform (Ewing & Maines 1992). However, they express very little ferritin at baseline and have relatively limited capacity to upregulate its expression, likely accounting at least in part for their selective vulnerability to Hb or iron (Kress et al. 2002, Regan et al. 2008).

Despite it obvious relevance to hemorrhagic CNS injuries, the effect of Hp on Hb neurotoxicity has not been extensively evaluated, and has never been reported in cell culture systems with documented CD163 expression. We therefore utilized an established primary cortical cell culture model containing neurons, astrocytes, and microglia to test the hypothesis that Hp directly protects neurons against the toxicity of Hb.

Methods

Cortical cell cultures

All animal procedures were approved by the Thomas Jefferson University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Primary cultures were prepared from fetal C57BL/6 × 129/Sv mice bred exclusively at our animal facility at 14–17 days gestation. These cultures contain neurons on a monolayer of glial cells consisting of ~2–3% microglia and >90% GFAP+ astrocytes (Jaremko et al. 2010). This mixed culture system offers two important advantages over pure neuronal cultures. First, it permits direct comparison of Hb-Hp and Hb uptake by neurons and glia. Second, unlike pure neuronal cultures, neurons in mixed cultures do not require addition of antioxidants and iron-poor transferrin, which protect against Hb toxicity (Brewer 1995, Chen-Roetling et al. 2011). Cultures were prepared in 24-well Primaria plates (Corning, Durham, NC, USA) using a method that has been previously described in detail (Rogers et al. 2003). Two-thirds of the culture medium was exchanged with fresh medium on days 5 and 9 in vitro, and daily after day 10. Feeding medium contained Minimal Essential Medium (MEM, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), equine serum (10%, Hyclone, Logan UT, USA), and glutamine (2 mM). Pure neuronal cultures were plated in serum free Neurobasal Medium with B27 supplement as previously described (Regan et al. 2008), and were used only in confirmatory immunostaining experiments.

Hemoglobin toxicity experiments

Experiments were conducted on days 12–19 in vitro. Before all cytotoxicity experiments, two-thirds of the culture medium was exchanged with MEM containing 10 mM glucose (MEM10) on the day prior to Hb treatment, thereby reducing the serum content to 3.3%. Cultures were randomly selected from 24-well culture dishes and were exposed to endotoxin-free hemoglobin (Hemosol Inc., Etobicoke, CA) in serum-free MEM10. The Hb concentrations used are toxic to neurons but not glia in this cell culture system (Regan & Panter 1993). All Hb concentrations are expressed as that of the tetramer.

Cell injury quantification

Cell injury was quantified by LDH release assay, which accurately measures the percentage neuronal loss in this model without the potential for bias associated with cell counts (Koh & Choi 1988). At the end of the exposure interval, 25 µl of medium was sampled from each well and its activity was determined by a kinetic assay described previously (Regan et al. 2008). The LDH signal present in sham-treated sister cultures was subtracted from all values to determine the activity produced by neuronal death. The latter was normalized to the signal produced in sister cultures treated continuously with 300 µM N-methyl-D-aspartate, which kills all neurons in this culture system.

Non-heme iron assay

Following the method of Pountney et al. (Pountney et al. 1999), cultures were washed three times with 500 µl saline; 25 µl 10 mM HEPES-buffered saline and 50 µl of 12.5% trichloroacetic acid with 2% sodium pyrophosphate were then added to each well. The lysate was collected in a 1.5 ml Eppendorf tube and boiled for 10 min. After centrifugation (10,000 × g, 5 min), the supernatant was removed, and an equal volume of 25 mM sodium ascorbate, 1 mM ferrozine and 1.05 M sodium acetate was added. Absorbance at 562 nm was then quantified and compared with that of serial dilutions of an iron standard solution (High-Purity Standards, Charleston SC, USA).

Immunoblotting and immunostaining

Standard methods that have been previously described in detail (Chen-Roetling et al. 2011) were utilized. Primary antibodies with catalog numbers and dilutions are as follows: CD163, Biorbyt LLC, Berkeley, CA, USA, orb13303, 1:100 and Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc, Dallas, TX, USA, sc-33560, 1:25; NeuN, EMD Millipore Corp, Temecula, CA, USA, MAB377X, 1:100; Iba-1, Wako Chemicals USA, Richmond, VA, USA, 019-19741, 1;100; HO-1, Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY, USA, ADI-SPA-895, 1:4000; ferritin, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA, F6136, 1:250; actin, Sigma-Aldrich, A2066, 1:1000.

Protein labeling

Hb and equimolar Hp-Hb complexes (2 mg/ml total) were fluorescently labeled with Alexa Fluor 568 using a kit purchased from Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA. The solution was washed free of unbound dye using Amicon Ultra centrifugal filter units with 10K membranes (Millipore).

Statistical methods

Minimum sample size was calculated using a two tailed α= 0.05 and β = 0.20 (Power = 0.8), and the expected standard deviation for the parameters tested, based on extensive prior experience in this cell culture model. All data were analyzed with one way ANOVA. The significance of differences between groups was determined with the Bonferroni multiple comparisons test.

Results

Haptoglobin increases neuronal vulnerability to hemoglobin

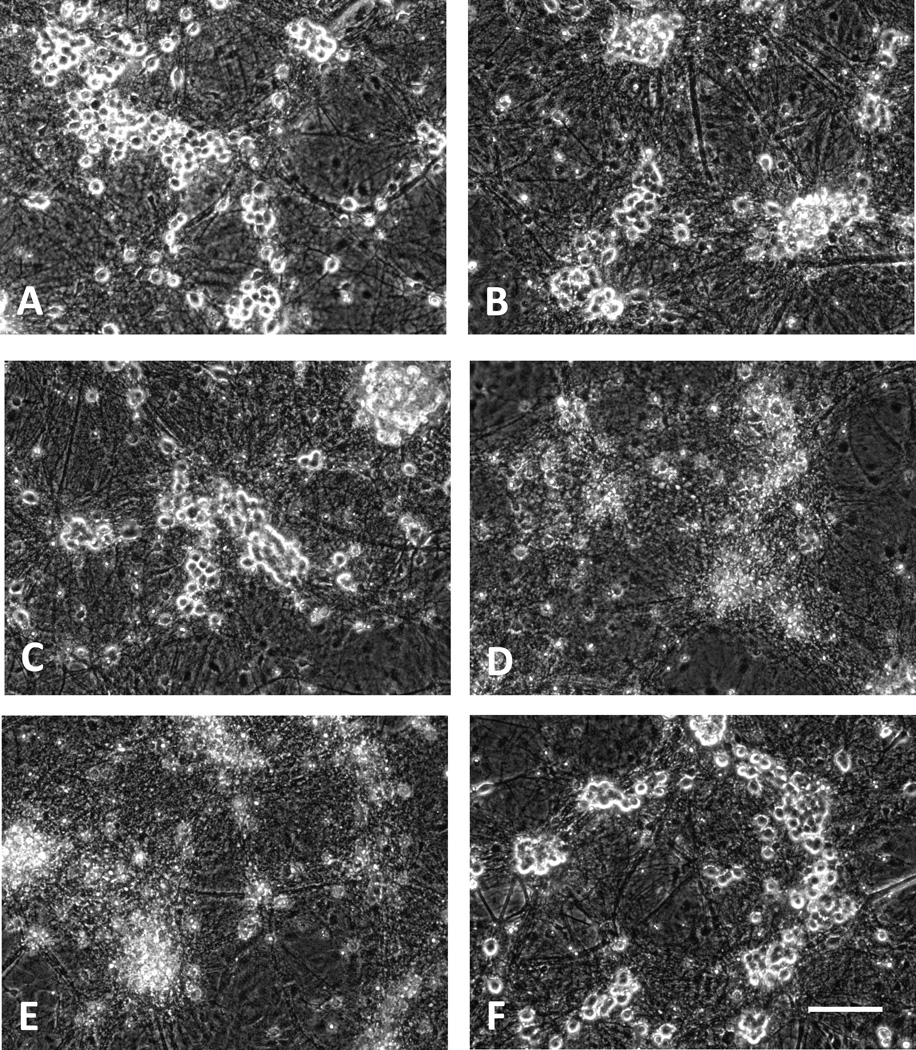

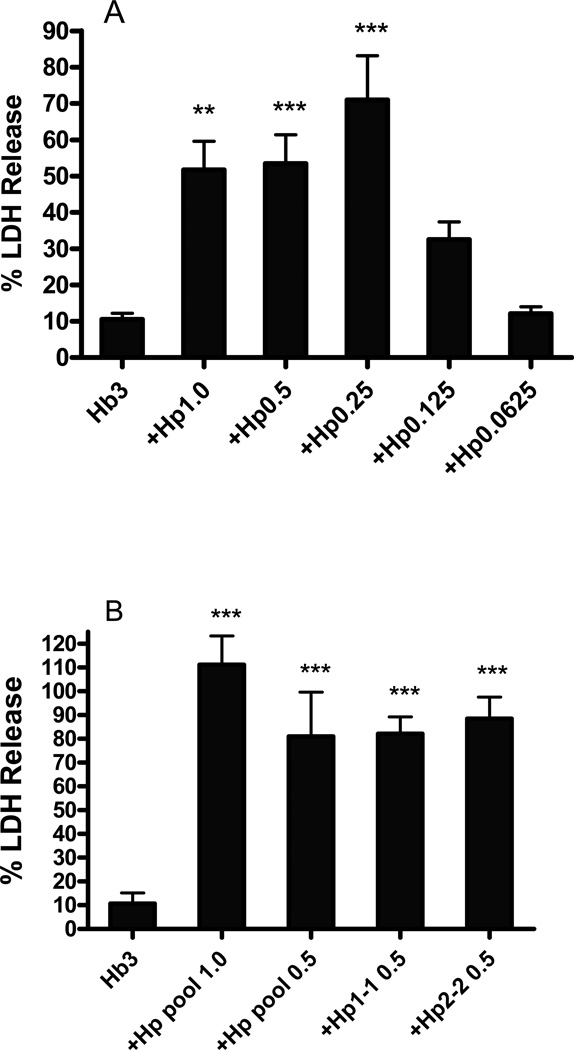

Neurons are easily identified in this mixed neuron-glia culture system under phase-contrast microscopy by their phase-bright and well-defined cell bodies that tend to associate in small groups, connected by a network of processes (Fig. 1A). Initial experiments tested the effect of human Hp provided by Bio Products Laboratory (BPL), Herfordshire, UK, which is enriched in the 1-1 Hp phenotype (Deuel et al. 2015). Treatment with 3 µM Hb for 24 hours resulted in loss of only 10–20% of neurons, as measured by LDH release assay. Concomitant treatment with 0.25–1 mg/ml Hp, concentrations sufficient to bind most or all Hb in the culture, increased neuron loss five to sevenfold, without producing any change in appearance of the background glial monolayer (Figs. 1D–E, 2A). Treatment with Hp alone at these concentrations was nontoxic (Fig 1F), and did not result in significant LDH release. Hp concentrations lower than 0.25 mg/ml had no significant effect on Hb neuronal injury. The glial monolayer remained intact, consistent with prior observations in multiple studies testing Hb neuronal toxicity in these cultures.

Figure 1.

Morphological appearance of cultures treated with hemoglobin (Hb) and haptoglobin (Hp). A) Phase-contrast image of control culture subjected to medium exchange only. Phase-bright neuron cell bodies are connected by processes and are attached to a confluent monolayer of glial cells. B) Culture treated with 3 µM Hb alone for 24 hours. C–E) Cultures treated with 3 µM Hb plus 0.125 mg/ml, 0.25 mg/ml and 1.0 mg/ml Hp, respectively, demonstrating widespread neuronal loss at higher Hp concentrations. F) Culture treated with 1 mg/ml Hp alone. Scale bar = 100 µm.

Figure 2.

Haptoglobin increases neuronal vulnerability to hemoglobin. Percentage neuron loss as measured by LDH release assay in cultures treated for 24 hours with Hb 3µM alone or with indicated concentrations (mg/ml) of haptoglobin. A) Testing BPL haptoglobin, enriched in 1-1 phenotype; B) testing pooled Hp, Hp 1-1 and Hp 2-1 from Athens Research and Technology. The weak LDH signal in control cultures undergoing medium exchange only was subtracted from all values to calculate the signal produced by cell death. All values were scaled to those in sister cultures from the same plating that were treated with 300 µM NMDA (=100), which kills all neurons without injuring glia. **P < 0.01, **P < 0.001 v. value in cultures treated with Hb only, n = 4–12/condition.

In order to determine if this unexpected result was unique to BPL Hp, additional experiments were conducted using human Hp 1-1 and 2-2 phenotypes purchased from Athens Research and Technology Athens, GA, USA (Catalog Nos. 16-16-080116-1/1-LEL and 16-16-080116-2/2), and also their pooled plasma Hp that contains all three phenotypes (Hp 1-1, 2-1 and 2-2, Catalog No. 16-16-080116-LEL). These products increased neuron death to an extent very similar to that of BPL Hp (Fig. 2B)

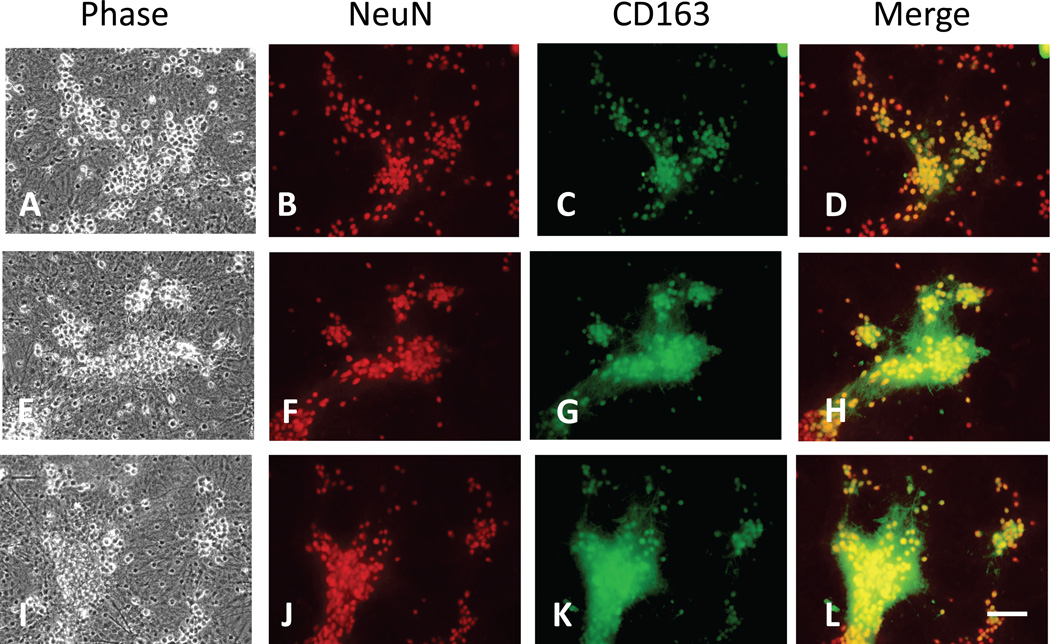

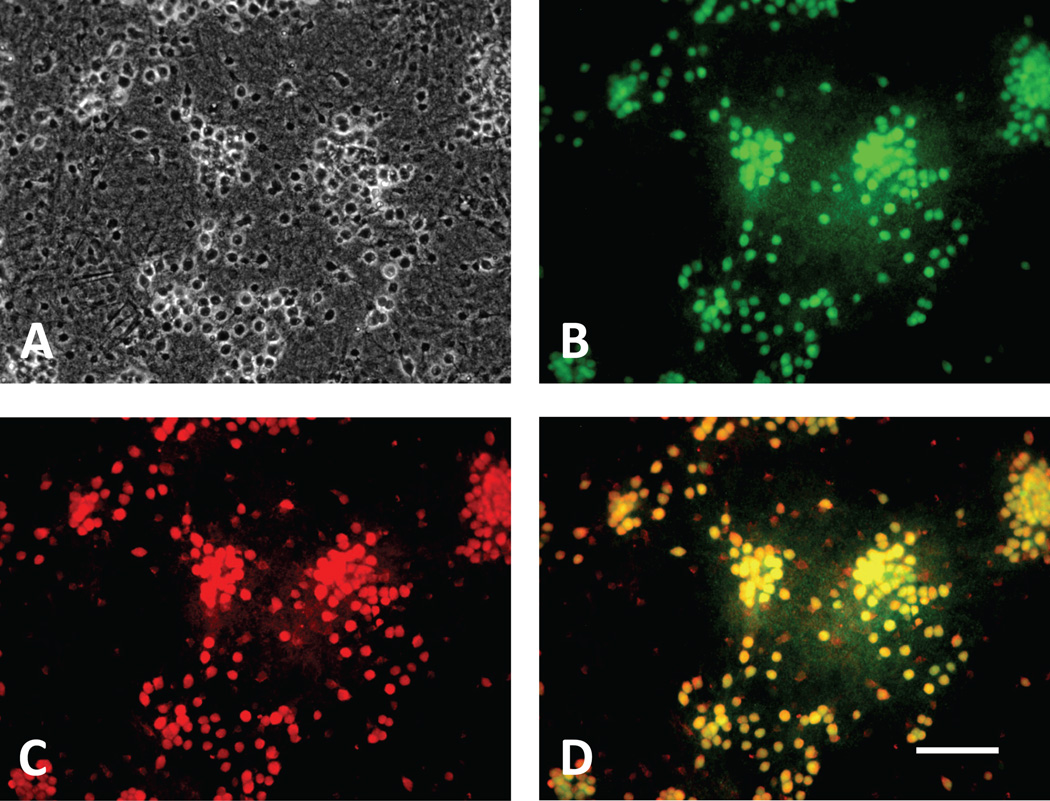

Neurons express CD163

In control cultures undergoing media exchange only, CD163 co-localized with NeuN in phase-bright cells with the typical appearance of neuron somata (Fig. 3A–D), using a primary antibody (Biorbyt orb13303) raised against a peptide contained in the extracellular SCRC9 domain of CD163 (Schaer et al. 2001); minimal staining was observed in neuronal processes. The glial monolayer between neuron clusters, which consists predominantly of GFAP+ astrocytes in this culture system (Chen-Roetling et al. 2009), was unstained. In cultures treated for 8 hours with Hb, CD163 immunoreactivity was also observed in the dense neuropil surrounding somata (Fig. 3E–H). This effect was not altered by concomitant treatment with haptoglobin (Fig. 3I–L). Neuronal CD163 expression was confirmed using another primary antibody raised against a peptide present in the transmembrane domain and cytoplasmic tail of mouse CD163 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology sc-33560), and using both mixed and pure neuronal cultures (images not shown).

Figure 3.

Primary cultured neurons express CD163. A–D) Control culture subjected to medium exchange only and fixed 8 hours later, immunostained with antibodies to CD163 and neuronal marker NeuN; CD163 immunoreactivity is largely limited to neuron somata, with minimal staining of neuropil and background glial monolayer. E–H) Culture treated with 10 µM Hb for 8 hours; CD163 immunreactivity has spread to dense neuropil surrounding clusters of neuron somata; I–L) Culture treated with 10 µM Hb plus 1 mg/ml Hp for 8 hours; immunostaining is similar to Hb alone culture, with some loss of phase-bright appearance of somata indicating early neurodegeneration. Scale bar = 100 µm.

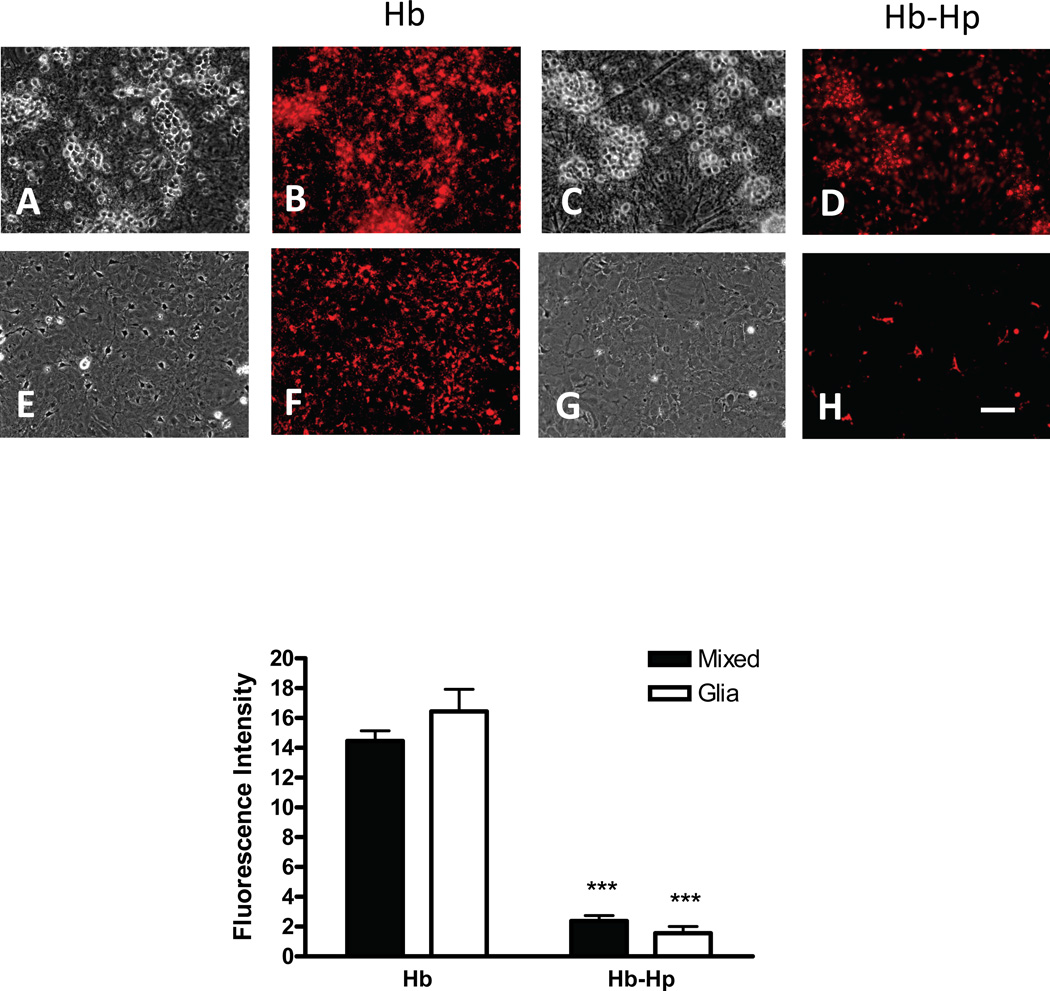

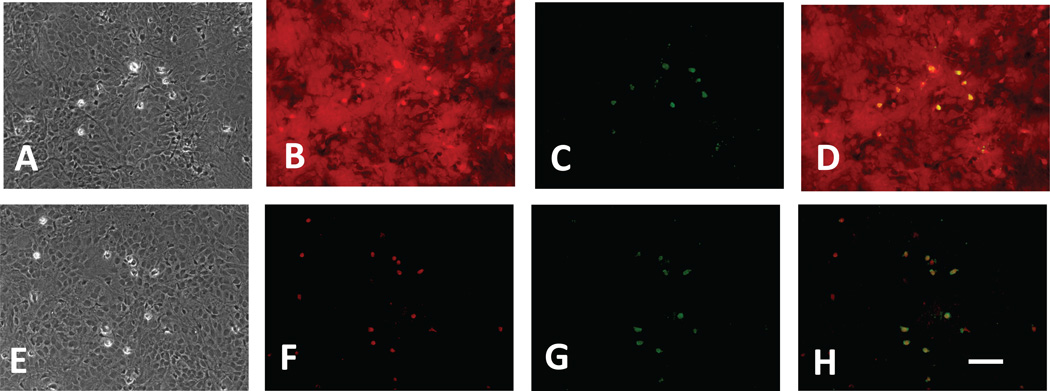

Consistent with CD163 expression by neurons, Hb-Hp complexes labeled with Alexa Fluor 568 also localized to NeuN+ fixed cells (Fig. 4), and to a smaller number of NeuN negative cells with the typical appearance of microglia. When labeled Hb-Hp complexes were applied to viable cultures (Fig. 5), punctate fluorescence was observed in cells with neuronal morphology, while diffuse fluorescence was apparent in cells with microglial morphology; again little uptake was observed in the astrocyte monolayer. The fluorescence signal observed in mixed cultures treated with labeled Hb alone was sixfold stronger than that produced by Hb-Hp complexes; Hb uptake was observed throughout cultures, including glial monolayers. In fixed glial monolayer cultures lacking neurons (Fig. 6), labeled Hb-Hp complexes localized to cells with the typical morphology of ameboid microglia; most of these cells were immunostained with anti-Iba-1. In contrast, labeled Hb diffusely stained fixed glial monolayer cultures, consistent with observations in viable cultures.

Figure 4.

Hb-Hp complexes localize to neuron somata. Fixed culture (A, phase contrast optics) was imaged two hours after incubation with anti-NeuN-FITC (B) and Hb-Hp-Alexa Fluor 568 conjugate (C, 1:25 dilution). Merged image (D) demonstrates that most Hb-Hp-Alexa Fluor+ cells are neurons.

Figure 5.

Hp reduces Hb uptake. Viable mixed neuron-glial cultures (A–D, fluorescence and corresponding phase contrast images) and glial cultures (E–H) were treated with Hb-Alexa Fluor 568 conjugate (A,B,E,F) or Hb-Hp-Alexa Fluor 568 conjugate (C,D,G,H). Bars represent mean fluorescence intensity of images (n = 5/condition) captured after 8 hour incubation. ***P<0.001 v. corresponding Hb condition. Scale bar = 100 µm.

Figure 6.

Hp directs Hb to microglia in glial cultures. Fixed glial cultures were treated with Hb-Alexa Fluor 568 conjugate (A–D) or Hb-Hp-Alexa Fluor 568 conjugate (E–H) for 2 hours. A,E: Phase contrast images showing confluent glial monolayers with scattered small phase-bright cells with the typical appearance of ameboid microglia; B,F) Hb-Alexa Fluor 568 conjugate diffusely stains culture (B), while Hb-Hp-Alexa Fluor 568 conjugate localizes to ameboid cells (F); C,G) Iba-1 immunostaining to detect activated microglia; D,H) Merged images. Scale bar = 100 µm.

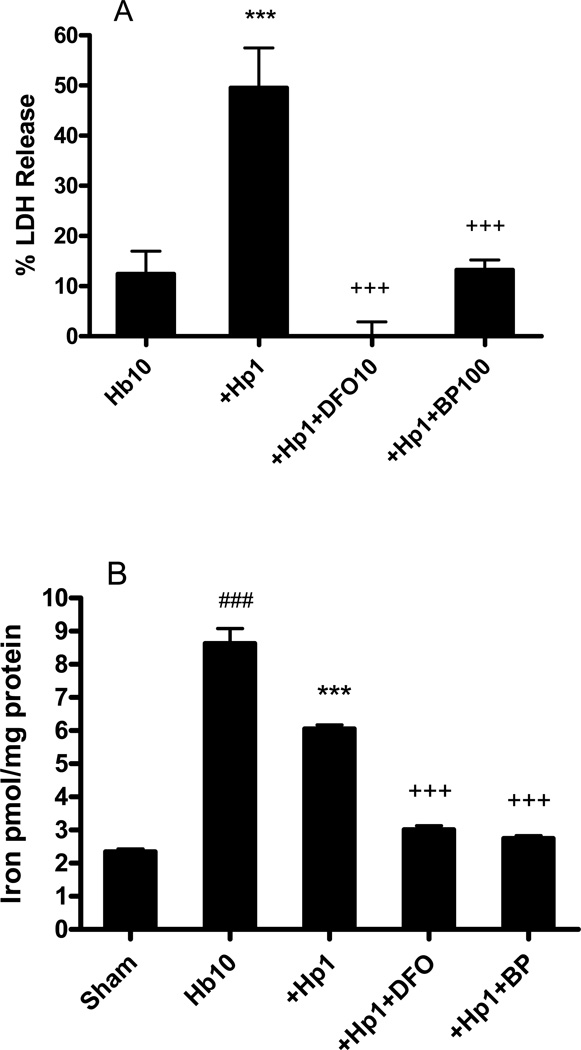

Hb-Hp toxicity is iron dependent

We have previously reported that the neuronal toxicity of Hb in this model is mediated by iron release and is completely blocked by iron chelators (Regan & Rogers 2003). The toxicity of the Hb-Hp complex was likewise reduced by deferoxamine (DFO) and 2,2’-bipyridyl (BP, Fig. 7). The increase in non-heme iron due to Hb treatment was weakly decreased by Hp, but was robustly reduced in cultures treated with DFO or BP (Fig 7B).

Figure 7.

Hb-Hp toxicity is iron dependent. A) Percentage neuron loss, as measured by LDH release assay, in cultures treated for 24 h with Hb 10 µM alone, Hb 10 µM plus Hp 1 mg/ml, or Hb, Hp plus indicated concentrations (µM) of deferoxamine (DFO) or 2,2’-bipyridyl (BP). B) Nonheme iron content in cultures treated for 24 hours as in A. ***P < 0.001 v. Hb alone condition, ###P < 0.001 v. sham, +++P < 0.001 v. Hb+Hp, n = 5–13/condition.

Haptoglobin decreases ferritin and HO-1 expression

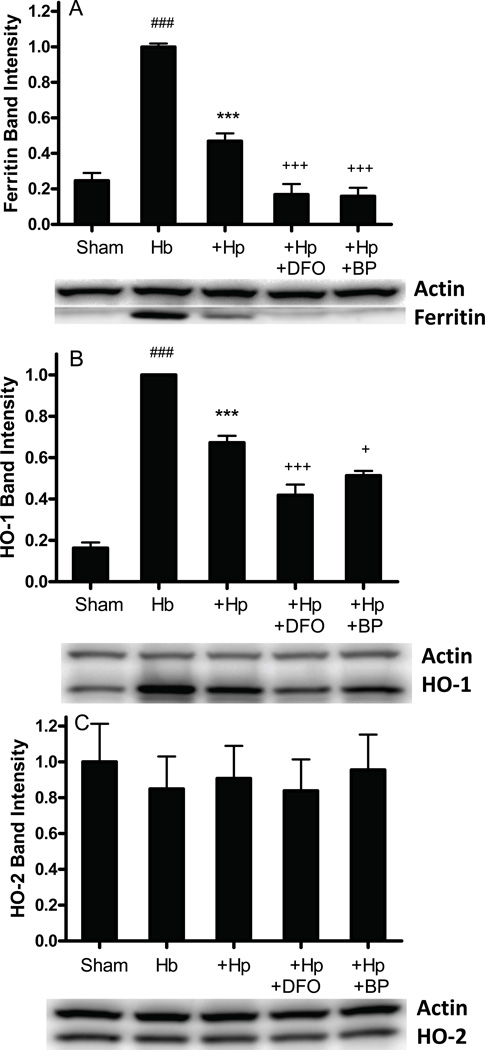

Ferritin is expressed predominantly by glial cells in these cultures, and attenuates the neuronal toxicity of Hb when overexpressed (Regan et al. 2008). It was increased fourfold by Hb treatment; this induction was reduced by about 70% by Hp and was completely blocked by iron chelators (Fig. 8A). HO-1 is also expressed by glial cells in this culture system, while HO-2 is the predominant neuronal isoform (Rogers et al. 2003, Chen-Roetling & Regan 2006) Hp reduced HO-1 expression in Hb-treated cultures by about 40%, but had no effect on HO-2 (Fig. 8B–C).

Figure 8.

Hp reduces ferritin and HO-1 expression in Hb-treated cultures. Ferritin, heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) and HO-2 expression in cultures treated with Hb 10 µM alone, with Hp 1 mg/ml, or with Hp plus deferoxamine (DFO) 10 µM or 2,2’-Bipyridyl (BP) 100 µM for 8 hours. ***P<0.001 v. Hb alone, ###P<0.001 v. sham, +++P < 0.001, +P < 0.05 v. Hb+Hp, n = 4/condition.

Discussion

This study provides three observations that may be relevant to neuronal injury after hemorrhagic CNS injuries. First, binding of Hb to Hp surprisingly enhanced its toxicity in primary cortical cultures containing neurons and glia; this effect was consistent across four human Hp preparations with differing phenotypes. Second, neurons express CD163 in this model, in agreement with a recent observation in vivo (Garton et al. 2016). Third, Hp binding reduced total Hb uptake by cultures and also directed it away from astrocytes, a cell population that robustly upregulates ferritin after Hb treatment (Regan et al. 2008). Since the neuronal toxicity of Hb is inversely related to ferritin expression, the latter effect may account at least in part for increased neuronal loss in Hb-Hp treated cultures.

The reference range for human serum haptoglobin is 0.3–2.0 mg/ml, while CSF concentrations are ~1 µg/ml (Galea et al. 2012, ARUP 2016). The Hp concentrations used in this study are similar to those in serum, and may be relevant immediately following hemorrhage and also after blood-brain barrier breakdown. Human haptoglobin is constructed of α and β chains and is expressed in dimeric and polymeric phenotypes. Clinical studies have suggested an association between the polymeric 2-2 phenotype, cerebral vasospasm, and poor outcome after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) and ICH (Kantor et al. 2014, Leclerc et al. 2015, Murthy et al. 2015, Borsody et al. 2006). The putative mechanism mediating this phenomenon is a reduced capacity of this phenotype for Hb binding (Javid 1965). However, Lipiski et al. have reported that the 1-1 and 2-2 phenotypes were equally effective at attenuating the toxicity of Hb-oxidized LDL in endothelial cultures (Lipiski et al. 2013). Both phenotypes had a similar effect on Hb binding, renal iron deposition and blood pressure when administered with Hb to guinea pigs. In the present study, both the 1-1 and 2-2 phenotypes increased neuronal death after Hb treatment to a similar extent, suggesting that Hp phenotype is not a significant determinant of its effect on cultured neurons exposed to toxic Hb concentrations.

CD163 is a widely-utilized marker of monocytes/macrophages and microglia, and immunoreactivity is often considered to be sufficient evidence to assign cells in histological sections to these lineages. The specificity of this marker has been challenged by reports that it is expressed by high-grade tumor cells (Shabo et al. 2009, Shabo et al. 2008), and also in astrocyte-like cells in a rat model of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Trias et al. 2013). More recently, Garton et al. (Garton et al. 2016) reported CD163 expression in neonatal rat hippocampal neurons and in primary cultured rat fetal neurons. Our results extend the latter observation to cortical neurons cultured from fetal mice, and suggest that the Hb-Hp-CD163 axis may modulate the neuronal toxicity of hemoglobin after fetal or neonatal intracranial hemorrhage.

Labeled protein experiments demonstrated that Hp had two significant effects. First, it reduced overall Hb uptake, with the fluorescence intensity of viable cultures incubated with labeled Hb-Hp complexes approximately one-sixth that of cultures treated with labeled Hb alone. Second, it shifted Hb away from glial monolayers, which contain mainly astrocytes (Jaremko et al. 2010), and directed it toward neurons and microglia. This observation is consistent with the minimal expression of CD163 in the glial monolayer of mixed cultures. In contrast, treatment with labeled Hb per se resulted in widespread staining throughout both glial and mixed cultures. CD163 is the sole Hb scavenger receptor described to date (Schaer et al. 2006b), but diffuse Hb uptake in glia indicates the presence of an alternate pathway. The relative exclusion of labeled Hb-Hp by glial monolayers is consistent with a process that is more specific than fluid phase endocytosis.

In contrast to neurons, glia are very resistant to Hb, due at least in part to their rapid upregulation of ferritin and HO-1 in response to Hb treatment (Chen-Roetling & Regan 2006, Regan et al. 2002). The strong staining of astrocyte-rich glial monolayers with labeled Hb suggests that astrocytes may be the primary scavengers of free Hb in this cell culture model. The benefits of Hb uptake by astrocytes may extend beyond the obvious limiting of the supply available to more vulnerable neurons. Astrocytes respond to Hb by inducing ferritin, a heteropolymer with a capacity for sequestering ~4000 iron atoms per molecule (Arosio & Levi 2002). Although neurons make little ferritin and export excess iron (Moos & Morgan 2004), they are robustly protected in mixed cultures by ferritin upregulation, likely due to iron uptake and ferritin secretion by astrocytes (Regan et al. 2008, Greco et al. 2010, Hohnholt & Dringen 2013). Haptoglobin reduced ferritin induction in Hb-treated mixed cultures by approximately 70%, consistent with the observed decrease in glial Hb staining. The reduced capacity for iron detoxification may have contributed to the increased neuronal toxicity of the Hb-Hp complex, which like Hb is iron-dependent.

The observation that haptoglobin increases neuronal vulnerability to Hb is in contrast to a prior report that Hp knockout worsened outcome in an adult mouse ICH model, while overexpression was protective (Zhao et al. 2009). Cell populations expressing CD163 were not assessed in the latter study, so the discrepancy may reflect differences in fetal and adult CNS cells. It is also possible that the protective effect of Hp in hemorrhagic stroke models is not mediated by sequestering and stabilizing Hb, but rather by the potent effects of Hb-Hp complexes on macrophage phenotype. Hb-Hp uptake suppresses HLA class 2 protein expression by cultured human macrophages while increasing their antioxidant defenses (Schaer et al. 2006a, Kaempfer et al. 2011). Downregulation of the inflammatory response in the highly oxidative environment surrounding a hematoma may account for some or all of the protection provided by Hp, rather than direct mitigation of Hb neuronal toxicity.

The benefits of Hp after intravascular hemolysis have largely been assumed to extend to hemorrhagic stroke, with the only concerns related to the association of the Hp2-2 phenotype and poor outcome after SAH and ICH (Kantor et al. 2014, Leclerc et al. 2015, Murthy et al. 2015, Borsody et al. 2006). The results of this study indicate that Hp alters Hb trafficking in a manner that may be deleterious to CD163+ neurons in a hemorrhagic environment. It is acknowledged that this cell culture model provides information that is relevant to only a part of the complex injury cascades initiated by intracranial hemorrhage. In particular, the inflammatory response is minimal due to the relatively small number of microglia and the absence of blood-derived leukocytes. The proteome of cultured cells may also differ significantly from that in vivo, which may affect neuronal vulnerability to Hb and other neurotoxins. However, detection of CD163 in neonatal rat hippocampal neurons after intraventricular hemorrhage demonstrates that its expression is not solely a cell culture phenomenon (Garton et al. 2016). Its relevance to hemorrhagic CNS injuries in adults remains undefined and seems a worthy topic for future investigation.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH grants R21NS088986, RO1NS079500 and R01NS095205.

Abbreviations

- BP

2,2’-bipyridyl

- DFO

deferoxamine

- Hb

hemoglobin

- HO

heme oxygenase

- Hp

haptoglobin

- ICH

intracerebral hemorrhage

- LDH

lactate dehydrogenase

- SAH

subarachnoid hemorrhage

Footnotes

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- Arosio P, Levi S. Ferritin, iron homeostasis, and oxidative damage. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;33:457–463. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00842-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ARUP. Haptoglobin: ARUP Lab Tests. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- Borsody M, Burke A, Coplin W, Miller-Lotan R, Levy A. Haptoglobin and the development of cerebral artery vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurology. 2006;66:634–640. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000200781.62172.1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer GJ. Serum-free B27/neurobasal medium supports differentiated growth of neurons from the striatum, substantia nigra, septum, cerebral cortex, cerebellum, and dentate gyrus. J Neurosci Res. 1995;42:674–683. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490420510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen-Roetling J, Chen L, Regan RF. Apotransferrin protects cortical neurons from hemoglobin toxicity. Neuropharmacology. 2011;60:423–431. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen-Roetling J, Li Z, Chen M, Awe OO, Regan RF. Heme oxygenase activity and hemoglobin neurotoxicity are attenuated by inhibitors of the MEK/ERK pathway. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56:922–928. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2009.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen-Roetling J, Regan RF. Effect of heme oxygenase-1 on the vulnerability of astrocytes and neurons to hemoglobin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;350:233–237. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.09.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deuel JW, Vallelian F, Schaer CA, Puglia M, Buehler PW, Schaer DJ. Different target specificities of haptoglobin and hemopexin define a sequential protection system against vascular hemoglobin toxicity. Free Radic Biol Med. 2015;89:931–943. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etzerodt A, Kjolby M, Nielsen MJ, Maniecki M, Svendsen P, Moestrup SK. Plasma clearance of hemoglobin and haptoglobin in mice and effect of CD163 gene targeting disruption. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;18:2254–2263. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing JF, Maines MD. In situ hybridization and immunohistochemical localization of heme oxygenase-2 mRNA and protein in normal rat brain: differential distribution of isozyme 1 and 2. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 1992;3:559–570. doi: 10.1016/1044-7431(92)90068-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea J, Cruickshank G, Teeling JL, Boche D, Garland P, Perry VH, Galea I. The intrathecal CD163-haptoglobin-hemoglobin scavenging system in subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurochem. 2012;121:785–792. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2012.07716.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganz T. Macrophages and systemic iron homeostasis. J Innate Immun. 2012;4:446–453. doi: 10.1159/000336423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garton T, He Y, Garton HJ, Keep RF, Xi G, Strahle JM. Hemoglobin-induced neuronal degeneration in the neonatal hippocampus after intraventricular hemorrhage. Brain Res. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2015.12.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greco TM, Seeholzer SH, Mak A, Spruce L, Ischiropoulos H. Quantitative mass spectrometry-based proteomics reveals the dynamic range of primary mouse astrocyte protein secretion. J Proteome Res. 2010;9:2764–2774. doi: 10.1021/pr100134n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohnholt MC, Dringen R. Uptake and metabolism of iron and iron oxide nanoparticles in brain astrocytes. Biochem Soc Trans. 2013;41:1588–1592. doi: 10.1042/BST20130114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang FP, Xi G, Keep RF, Hua Y, Nemoianu A, Hoff JT. Brain edema after experimental intracerebral hemorrhage: role of hemoglobin degradation products. J. Neurosurg. 2002;96:287–293. doi: 10.3171/jns.2002.96.2.0287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaremko KM, Chen-Roetling J, Chen L, Regan RF. Accelerated Hemolysis and Neurotoxicity in Neuron-Glia-Blood Clot Co-cultures. J Neurochem. 2010;114:1063–1073. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06826.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javid J. The Effect of Haptoglobin Polymer Size on Hemoglobin Binding Capacity. Vox Sang. 1965;10:320–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.1965.tb01396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaempfer T, Duerst E, Gehrig P, Roschitzki B, Rutishauser D, Grossmann J, Schoedon G, Vallelian F, Schaer DJ. Extracellular hemoglobin polarizes the macrophage proteome toward Hb-clearance, enhanced antioxidant capacity and suppressed HLA class 2 expression. J Proteome Res. 2011;10:2397–2408. doi: 10.1021/pr101230y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantor E, Bayir H, Ren D, et al. Haptoglobin genotype and functional outcome after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 2014;120:386–390. doi: 10.3171/2013.10.JNS13219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapralov A, Vlasova II, Feng W, et al. Peroxidase activity of hemoglobin-haptoglobin complexes: covalent aggregation and oxidative stress in plasma and macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:30395–30407. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.045567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh JY, Choi DW. Vulnerability of cultured cortical neurons to damage by excitotoxins: Differential susceptibility of neurons containing NADPH-diaphorase. J. Neurosci. 1988;8:2153–2163. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-06-02153.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kress GJ, Dineley KE, Reynolds IJ. The relationship between intracellular free iron and cell injury in cultured neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes. J Neurosci. 2002;22:5848–5855. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-14-05848.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara FA, Kahn SA, da Fonseca AC, et al. On the fate of extracellular hemoglobin and heme in brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29:1109–1120. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leclerc JL, Blackburn S, Neal D, Mendez NV, Wharton JA, Waters MF, Dore S. Haptoglobin phenotype predicts the development of focal and global cerebral vasospasm and may influence outcomes after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:1155–1160. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1412833112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim SK, Ferraro B, Moore K, Halliwell B. Role of haptoglobin in free hemoglobin metabolism. Redox Rep. 2001;6:219–227. doi: 10.1179/135100001101536364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipiski M, Deuel JW, Baek JH, Engelsberger WR, Buehler PW, Schaer DJ. Human Hp1-1 and Hp2-2 phenotype-specific haptoglobin therapeutics are both effective in vitro and in guinea pigs to attenuate hemoglobin toxicity. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;19:1619–1633. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.5089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos T, Morgan EH. The metabolism of neuronal iron and its pathogenic role in neurological disease: review. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1012:14–26. doi: 10.1196/annals.1306.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos T, Rosengren Nielsen T, Skjorringe T, Morgan EH. Iron trafficking inside the brain. J Neurochem. 2007;103:1730–1740. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murthy SB, Levy AP, Duckworth J, Schneider EB, Shalom H, Hanley DF, Tamargo RJ, Nyquist PA. Presence of haptoglobin-2 allele is associated with worse functional outcomes after spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. World Neurosurg. 2015;83:583–587. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2014.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panter SS, Sadrzadeh SM, Hallaway PE, Haines JL, Anderson VE, Eaton JW. Hypohaptoglobinemia associated with familial epilepsy. J Exp Med. 1985;161:748–754. doi: 10.1084/jem.161.4.748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pountney DJ, Konijn AM, McKie AT, Peters TJ, Raja KB, Salisbury JR, Simpson RJ. Iron proteins of duodenal enterocytes isolated from mice with genetically and experimentally altered iron metabolism. Br J Haematol. 1999;105:1066–1073. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regan RF, Chen M, Li Z, Zhang X, Benvenisti-Zarom L, Chen-Roetling J. Neurons lacking iron regulatory protein-2 are highly resistant to the toxicity of hemoglobin. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;31:242–249. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regan RF, Kumar N, Gao F, Guo YP. Ferritin induction protects cortical astrocytes from heme-mediated oxidative injury. Neuroscience. 2002;113:985–994. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00243-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regan RF, Panter SS. Neurotoxicity of hemoglobin in cortical cell culture. Neurosci. Lett. 1993;153:219–222. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90326-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regan RF, Rogers B. Delayed treatment of hemoglobin neurotoxicity. J Neurotrauma. 2003;20:111–120. doi: 10.1089/08977150360517236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers B, Yakopson V, Teng ZP, Guo Y, Regan RF. Heme oxygenase-2 knockout neurons are less vulnerable to hemoglobin toxicity. Free Rad Biol Med. 2003;35:872–881. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00431-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadrzadeh SMH, Graf E, Panter SS, Hallaway PE, Eaton JW. Hemoglobin: A biologic Fenton reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 1984;259:14354–14356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaer CA, Schoedon G, Imhof A, Kurrer MO, Schaer DJ. Constitutive endocytosis of CD163 mediates hemoglobin-heme uptake and determines the noninflammatory and protective transcriptional response of macrophages to hemoglobin. Circ Res. 2006a;99:943–950. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000247067.34173.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaer DJ, Boretti FS, Hongegger A, Poehler D, Linnscheid P, Staege H, Muller C, Schoedon G, Schaffner A. Molecular cloning and characterization of the mouse CD163 homologue, a highly glucocorticoid-inducible member of the scavenger receptor cysteine-rich family. Immunogenetics. 2001;53:170–177. doi: 10.1007/s002510100304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaer DJ, Schaer CA, Buehler PW, Boykins RA, Schoedon G, Alayash AI, Schaffner A. CD163 is the macrophage scavenger receptor for native and chemically modified hemoglobins in the absence of haptoglobin. Blood. 2006b;107:373–380. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabo I, Olsson H, Sun XF, Svanvik J. Expression of the macrophage antigen CD163 in rectal cancer cells is associated with early local recurrence and reduced survival time. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:1826–1831. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabo I, Stal O, Olsson H, Dore S, Svanvik J. Breast cancer expression of CD163, a macrophage scavenger receptor, is related to early distant recurrence and reduced patient survival. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:780–786. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trias E, Diaz-Amarilla P, Olivera-Bravo S, et al. Phenotypic transition of microglia into astrocyte-like cells associated with disease onset in a model of inherited ALS. Front Cell Neurosci. 2013;7:274. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2013.00274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Hua Y, Keep RF, Nakemura T, Hoff JT, Xi G. Iron and iron-handling proteins in the brain after intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2003;34:2964–2969. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000103140.52838.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi GH, Keep RF, Hoff JT. Erythrocytes and delayed brain edema formation following intracerebral hemorrhage in rats. J. Neurosurg. 1998;89:991–996. doi: 10.3171/jns.1998.89.6.0991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Song S, Sun G, Strong R, Zhang J, Grotta JC, Aronowski J. Neuroprotective role of haptoglobin after intracerebral hemorrhage. J Neurosci. 2009;29:15819–15827. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3776-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]