This is the second article in a series on population healthcare.

Levels of care: the first dimension

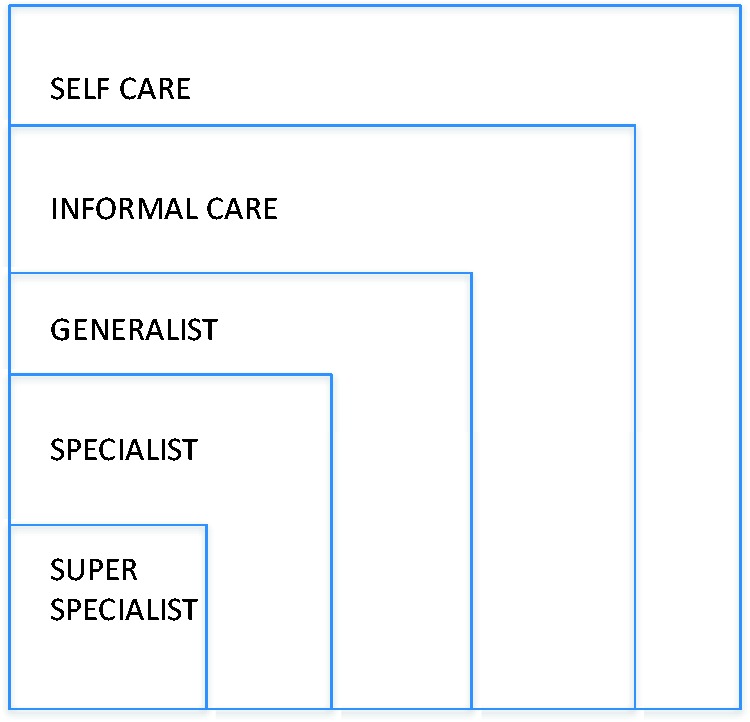

When clinicians think about healthcare, they usually think about primary, secondary and tertiary levels of care or generalist, specialist and super-specialist, to use another taxonomy. The latter taxonomy is perhaps more accurate because many people use more specialist services as their first point of care.

These are well-established levels, but what is often overlooked, however, are the two other levels of care: self-care and informal care. Self-care is the most important type of care. Indeed, some people are now calling healthcare what people do for themselves with the professionals providing health services to support healthcare. Increasingly, it is recognised that even when people are receiving excellent technical care from a generalist, specialist or super-specialist, much depends on what they will do for themselves.

The second neglected level of care is informal care that is provided by family, friends, neighbours and voluntary services. In spite of the complaints about an uncaring society, informal care remains of vital importance, and many informal carers are themselves people with long-term health problems. If people in their 70s, 80s and 90s gave up caring, then the NHS would collapse tomorrow.

Thus, it is helpful to think about five levels of care: self-care, informal care, generalist care, specialist care and super-specialist care.

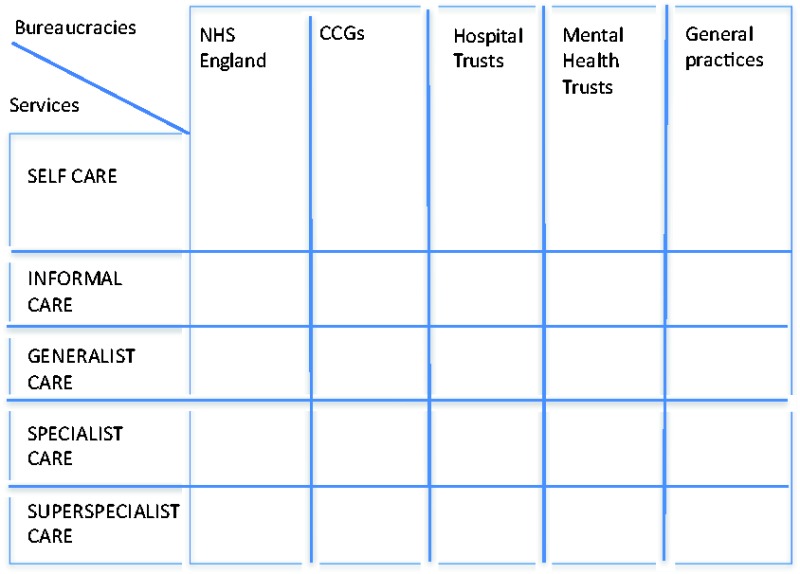

Bureaucracies: the second dimension

Although it has been fashionable to criticise bureaucracies, often understandably, bureaucracies are of vital importance. Bureaucratic procedures can be annoying and can often be counter-productive, and it is important to appreciate the limitations of bureaucracy. Great faith has been placed in bureaucratic reorganisation as a means of solving the challenge posed by increasing need and demand, but bureaucracies by themselves cannot do this as they are organisations designed to help with linear problems.

The importance of a good bureaucracy is apparent to whom anyone has ever worked in a country where there is not a good bureaucracy. A good bureaucracy is essential for the fair and open employment of staff and for the uncorrupt management of money. These are relatively simple linear tasks, and bureaucracies in healthcare do carry out simple tasks such as responding to requests to test a blood sample and then send the test back to the requestor. However, most problems are complex or non-linear. Even treating people with one diagnosis involves a whole range of individuals as well as the person with asthma and when we move up the level of complexity, for example, for people with multiple morbidity or people who are dying or single homeless people, bureaucratic solutions are not sufficient.

It is helpful to think of two types of bureaucracy: jurisdictions and institutions. The role of the jurisdiction is to allocate public money and, usually, it does this by relating to the institutions based on the levels of care. The allocation of resources to different groups is at present dominated by the traditional pattern of the second type of bureaucracy, healthcare providers as they are sometimes called namely hospitals, mental health, services and primary care teams. These bureaucracies too are very important, but attempts to meet the challenge that we face by reorganising the bureaucracies or by inspecting them or regulating them more frequently are unlikely to succeed because we are dealing with a complex challenge and complex challenges require a different approach.

In summary, therefore, we have two-dimensional healthcare at present shown in the figure below.

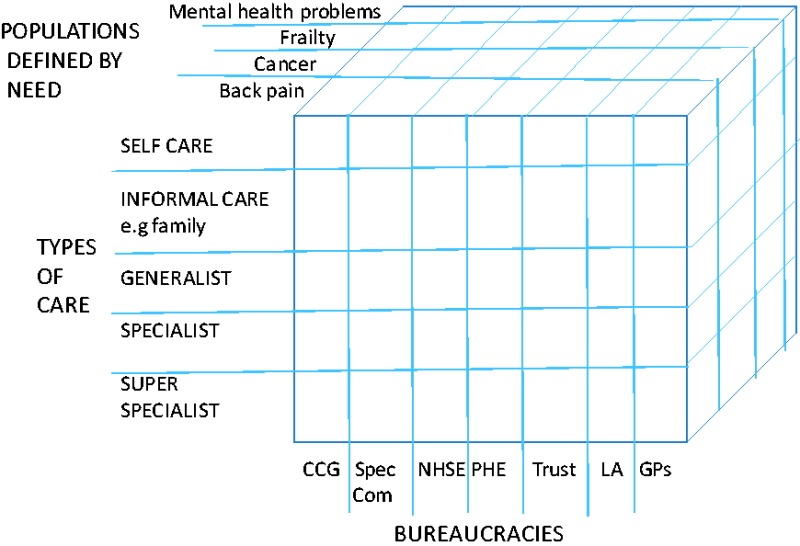

Populations in need: the third dimension

The levels of care are a relatively staple concept although the arrival of the smartphone is dramatically changing the relationships at different levels as people with health problems and their friends and neighbours have access to the world’s best knowledge and, unfortunately, a lot of very poor-quality knowledge as well.

Bureaucracies although designed for stability are frequently changed as people pursue the impossible dream of finding the perfect bureaucratic solution, a futile dream for the reasons outlined above namely linear organisations cannot meet the challenge posed by non-linear problems such as the problems posed by people with headache or people with epilepsy or people who are dying. What is required is a primary focus on populations defined by need and within that the development of population-based systems of care which inevitably relate to the different levels of care and the different bureaucracies.

Population-based healthcare is based on need, and the Rightcare Programme of the NHS in England developed a taxonomy that was partly based on need. In England, the NHS organises its finance not only by the bureaucracies but also with respect to programme budgeting and programme budgeting relates to programmes defined by the International Classification of Disease, for example, people with mental health problems or people with cancer. There are 23 of these and there is a very large variation in spend by different commissioning groups which has just evolved over the last 50 years and never been the result of formal decision-making. The variation in spend is relatively small compared with variation in service delivery that can be observed, for example, through the NHS Atlases of Variation, but a 1.7-fold variation in expenditure represents a huge amount of money with 10 or 20 million pounds more or less being spent in one population compared with another on one particular programme, for example, the programme for people with musculoskeletal problems.

Of course, many people have more than one problem and for this reason, it is necessary to complement the disease-based programmes with a number of programmes defined by need such as those listed below:

young people with severe disability;

older people with frailty; and

people at the end of life.

The best way to think of healthcare, therefore, is not as a matrix, hierarchy or a cube although the cube over simplifies the complexity of our task.

In organising such a complex activity, there are different options and leadership may rest with different dimensions for different aspects of the problem. However, the core business of the Health Service is not to run a good clinical commissioning group or provide good specialist care but to meet the needs of individuals and populations and for this reason, the third dimension, the Population Healthcare dimension is the most important of the three.

Population healthcare focuses primarily on populations defined by a common need which may be a symptom such as breathlessness, a condition such as arthritis or a common characteristic such as frailty in old age, not on institutions, or specialties or technologies. Its aim is to maximise value for those populations and the individuals within them but this requires a new approach to the involvement of doctors in leadership and management because it requires a subset of doctors to become involved not in the management of a service but in ensuring that the resources are used for all the people in need not just those who happen to have been referred.

Declarations

Competing interests

None declared.

Funding

None declared.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Guarantor

MG.

Contributorship

Sole authorship.

Provenance

Not commissioned; editorial review.